Abstract

In 1999, The American Journal of Pathology published an article entitled “Vascular Channel Formation by Human Melanoma Cells in Vivo and in Vitro: Vasculogenic Mimicry,” by Maniotis and colleagues, which ignited a spirited debate for several years and earned distinction as a citation classic. Tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry (VM) refers to the plasticity of aggressive cancer cells forming de novo vascular networks, which thereby contribute to perfusion of rapidly growing tumors, transporting fluid from leaky vessels, and/or connecting with the constitutional endothelial-lined vasculature. The tumor cells capable of VM share a plastic, transendothelial phenotype, which may be induced by hypoxia. Since VM was introduced as a novel paradigm for melanoma tumor perfusion, many studies have contributed new findings illuminating the underlying molecular pathways supporting VM in a variety of tumors, including carcinomas, sarcomas, glioblastomas, astrocytomas, and melanomas. Facilitating the functional plasticity of tumor cell VM are key proteins associated with vascular, stem cell, and hypoxia-related signaling pathways, each deserving serious consideration as potential therapeutic targets and diagnostic indicators of the aggressive, metastatic phenotype.

A great many studies in pathology have described a high degree of plasticity associated with aggressive cancer. Although such reports date back several centuries, for most of that time researchers did not have adequate tools to elucidate the etiology or the biological implications of tumor cell plasticity. Molecular tools, in particular, have become available only recently. As a noteworthy example, an article published by The American Journal of Pathology in 1999 presented a new interpretation for previous findings, describing cancer cells lining nonendothelial vascular channels within a tumor mass that contained red blood cells. The article, entitled “Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry,” by Maniotis et al,1 ignited a spirited debate for several years. A positive commentary about the significance of this article, entitled “Tumor plasticity allows vasculogenic mimicry, a novel form of angiogenic switch,” was provided by M.J. Bissell,2 and this was further supported by a Highlight note in Science3 discussing the implications of the original article with respect to the efficacy of angiogenesis inhibitors. A controversial commentary on the topic followed, entitled “Vasculogenic mimicry: how convincing, how novel, and how significant?”4 Briefly, the controversial aspects of this commentary regarding the original VM report focused on several aspects of the descriptive study and posed the following questions: i) Are the VM structures blood vessels, and do they contribute meaningfully to blood flow? ii) Can the identification of endothelial cells versus tumor cells in contact with the vascular lumen be established unambiguously? and iii) Is there a connection between endothelial cells and tumor cells in blood vessel walls? Subsequent debate raged on in publications, scientific meetings, and special workshops.

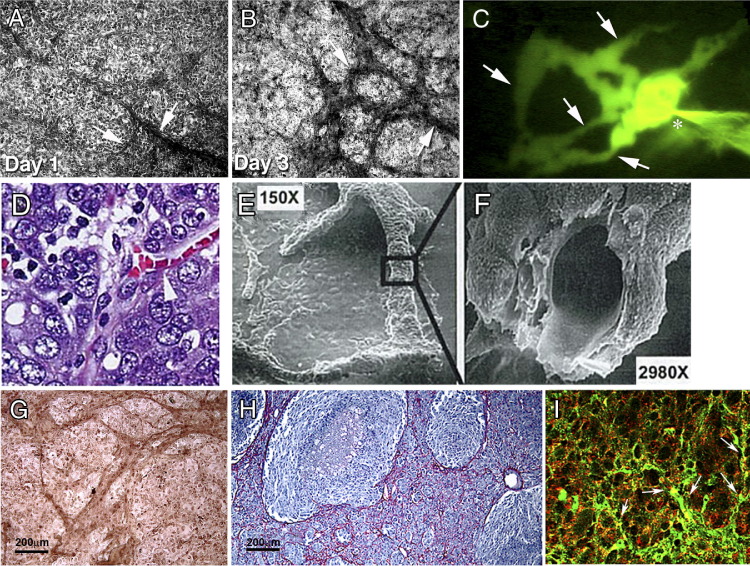

In retrospect, the 1999 article served as the foundational report defining tumor cell VM as the de novo formation of perfusable, matrix-rich, vasculogenic-like networks by aggressive tumor cells in three-dimensional matrices in vitro, which resembles the matrix-rich networks observed in aggressive tumors in patients (Figure 1). The hypothesis put forth at the time, based on the transport of injected fluorescent dye throughout VM networks in three-dimensional culture, was that tumor cell VM serves as a selective advantage to rapidly growing tumors by providing a perfusion pathway, transporting fluid from leaky vessels, and/or connecting with traditional, endothelial-lined vasculature. The genesis of this new paradigm would not have been possible without the molecular signature data of aggressive melanoma cells capable of VM, together with the three-dimensional assay showing the de novo formation of vascular structures. In addition, high resolution electron microscopy revealed the morphological details of the tumor cell-formed vessels and the similarities in ultrastructure between VM and traditional endothelial-lined vasculature.

Figure 1.

Tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry (VM) in vitro and in vivo. A and B: Aggressive human melanoma cells begin to form VM networks (arrows) in vitro in three-dimensional collagen I gels by the end of day 1 (A) and mature into more extensive VM networks (arrows) by day 3 (B). C: By day 14, similar network structures (arrows) can be perfused with a fluorescent dye (the injection site is indicated by an asterisk). D: H&E-stained histological section of high-grade human ovarian cancer shows RBCs within tumor cell-lined channels (arrowhead). E and F: Scanning electron microscopy of ovarian cancer cells cultured on three-dimensional collagen I matrices reveals formation of tubular structures (E) that contain a hollow lumen lined externally by flattened cancer cells when fractured in preparation (F). G and H: Immunostaining for Ln5 γ2 chain protein reveals VM networks in three-dimensional collagen I cultures of aggressive melanoma cells (G), similar to the VM laminin networks seen in a patient's melanoma histological tumor section (H). I: VM networks (arrows) are also seen in a histological section of aggressive melanoma coexpressing both EPHA2 (red) and VE-cadherin (green) under immunofluorescence microscopy (I). Original magnification: ×100 (A, B, and G); ×150 (E); ×200 (C and H); ×630 (D and I); ×2980 (F).

Reproduced with permission from Hendrix et al5 (A–C), Sood et al6 (D–F), Seftor et al7 (G and H), and Hess et al8 (I).

The initial morphological, clinical, and molecular characterization of VM was performed using human melanoma as a model. These tumor cells were shown to coexpress endothelial, embryonic/stem cell, and tumor markers; they were also shown to form channels, networks, and tubular structures rich in laminin, collagens IV and VI, and heparin sulfate proteoglycans and containing plasma and red blood cells. Collectively, these findings indicated a perfusion pathway for rapidly growing tumors, and possibly a metastatic escape route. Particularly noteworthy at the time was the rediscovery of an early report from 1966 (“The growth of the blood supply to melanoma transplants in the hamster cheek pouch,” by Warren and Shubik9) suggesting the perfusion of melanoma tumors via nonendothelial-lined channels. Another pertinent published observation, which inspired the term “tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry,” was the report of pseudo-vasculogenesis by cytotrophoblasts engaged in the formation of placentae.10 The type of plasticity demonstrated by cytotrophoblasts was very similar to that observed in human melanoma cells, which led to the understanding of tumor cell VM as a process that recapitulates early developmental events, including placenta formation and embryonic vasculogenesis.

Since the initial conceptualization of tumor cell VM in 1999, an impressive body of literature has provided mechanistic insights into the induction, formation, and targeting of VM across a variety of cancers, in more than 300 publications (too many to list here). In addition to melanoma, VM has been studied in carcinomas of the breast, ovary, lung, prostate, bladder, and kidney; in sarcomas (Ewing's, mesothelial, synovial, osteosarcoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma); and in gliomas, glioblastoma, and astrocytoma (reviewed by Paulis et al11). In several of these studies, including those of melanoma, Kaplan-Meier survival analyses indicated that patients with VM in their tumors have a poor clinical outcome, compared with patients whose tumors do not exhibit VM. From this accumulating body of evidence, we have a better perspective of the complexity comprising the tumor vasculature, which can be derived from a variety of sources, including angiogenic vessels, co-option of pre-existing vessels, intussusceptive microvascular growth, mosaic vessels lined by both tumor cells and endothelium, postnatal vasculogenesis, and VM.12 Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated the tumor origin of endothelial cells forming the vasculature in glioblastoma,13, 14 further complicating the clinical challenges of targeting genetically unstable and heterogeneous vasculature.

Tumor Cell Plasticity Underlies VM

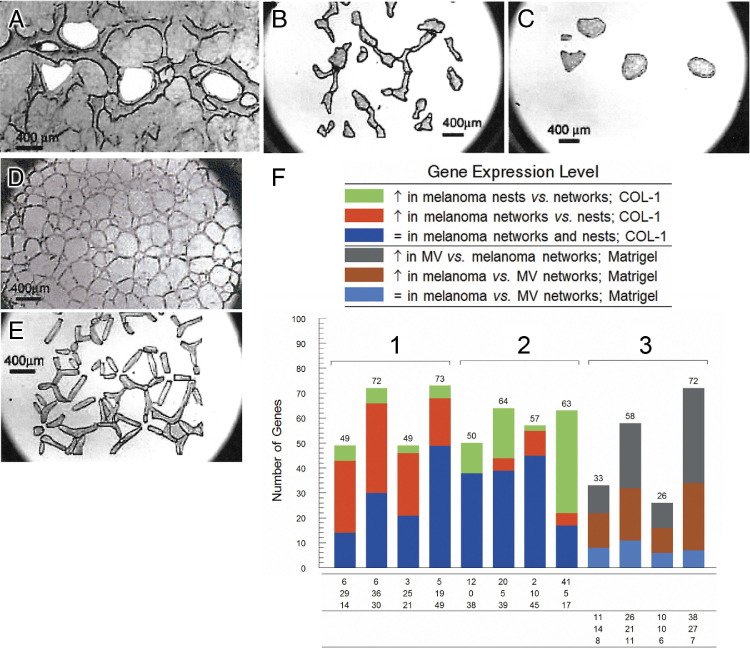

Tumor cells capable of VM exhibit a remarkable degree of plasticity, indicative of a multipotent phenotype usually associated with embryonic stem cells. The molecular signature of the tumor cell VM phenotype has revealed up-regulated expression of genes associated with embryonic progenitors, endothelial cells, vessel formation, matrix remodeling, and coagulation inhibitors, as well as down-regulation of genes predominantly associated with lineage-specific phenotype markers15 (Table 1). Although the initial microarray studies revealed the differential molecular profile of highly aggressive versus nonaggressive human melanoma cells,1, 15 later studies using laser capture microdissection and microgenomics profiling of melanoma VM networks versus endothelial-formed angiogenic vasculature confirmed the up-regulated expression of angiogenesis-related genes by the melanoma cells16 (Figure 2). In addition, this microgenomics approach confirmed that plastic tumor cells engaged in VM express key pluripotent stem cell markers. However, unlike normal embryonic progenitors, these tumor cells lack critical regulatory checkpoints, a characteristic that underlies their multipotent phenotype and contributes to unregulated growth and aggressive behavior.17 Recent studies have shed light on the induction of tumor cell plasticity pertinent to melanoma VM, with the finding that the hypoxic microenvironment contributes to the phenotype switch, specifically allowing melanoma cells to contribute to blood vessel formation.18 Collectively, these accumulating findings provide supportive evidence for alternative perfusion pathways found in aggressive tumors.

Table 1.

Gene Expression of Multipotent Aggressive Melanoma

| Gene symbol | Function | Ratio⁎ |

|---|---|---|

| NODAL | embryonic morphogen | 20 |

| NOTCH4 | stem cell-related transmembrane receptor | 5.3 |

| CDH5† | endothelial cell adhesion molecule | >100 |

| TIE1 | endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase | >100 |

| EPHA2 | epithelial cell kinase | 15 |

| NRP1 | VEGF receptor | 84 |

| ESM1 | endothelial cell surface protein | >100 |

| S1PR1 (previously EDG1) | endothelial G-coupled receptor; promotes angiogenesis | 33 |

| PDPN | elongates endothelial extensions; promotes migration, invasion, and tube formation | >100 |

| VEGFA | growth factor | 3.2 |

| VEGFC | growth factor ligand for FLT-4 | 3.4 |

| SERPINF1 (previously PEDF) | antiangiogenic growth factor | >100↓ |

| THBS1 | angiogenesis inhibitor | 58↓ |

| THBS2 | angiogenesis inhibitor | 11↓ |

| MMP1, MMP2, MMP14 | metalloproteinase | 6.3–21 |

| LOX | ECM remodeling; cell motility | >100 |

| LAMC2† | extracellular matrix | >100 |

| FN1 | extracellular matrix | 4.2 |

| TGM2 | matrix cross-linking enzyme | 38 |

| TFPI | coagulation inhibitor | 53 |

| TFPI2 | coagulation inhibitor | 24 |

| SPINT2 | serine protease inhibitor; coagulation inhibitor | 46 |

| F3 (alias CD142) | coagulation factor/VEGF regulator | 34 |

| PLAU | serine protease | >100 |

| PLAUR | GPI-linked urokinase receptor | 10.8 |

| HIF1A | hypoxia-inducible transcription factor | 2.0 |

| EPAS1 (alias HIF2A) | hypoxia-inducible transcription factor | 9.1 |

| MLANA (alias MART1) | pigment protein (melan-A) | 53↓ |

| TYRP1 | melanin process enzyme | >100↓ |

| SOX10 | melanin pathway transcription factor | >100↓ |

Altered gene expression in highly aggressive versus poorly aggressive melanomas identified by microarray and/or real-time RT-PCR analyses, and further validated by Western blot analysis. Differential expression of twofold or greater is reported for selected genes as a ratio, with a down-arrow (↓) indicating decreased expression.

CDH5 encodes the VE-cadherin protein (also known as cadherin-5). LAMC2 encodes the laminin 5 subunit γ2 protein.

Figure 2.

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) of melanoma VM versus endothelial cell angiogenesis. A: Holes left after excision of tumor cells by LCM from non-network regions (nests) in three-dimensional cultures of aggressive human melanoma cells. B: Isolated VM networks of melanoma cells on an LCM collection cap. C: Melanoma nests isolated from the VM culture in A on an LCM collection cap. D and E: Human microvascular endothelial cells (MV) on a Matrigel three-dimensional matrix (D) and isolated vascular networks of MV cells on an LCM collection cap (E). F: Using a gene array, the ratios were determined for relative gene expression in the melanoma cells isolated from the nests versus the networks under the different conditions, and three groups were identified: group 1, angiogenesis-specific; group 2, ECM and cell adhesion-specific expression for aggressive melanoma cells in networks versus nests on collagen I matrices; and group 3, angiogenesis-specific for aggressive melanoma cells versus MV on Matrigel. Scale bar = 400 μm.

Reproduced with permission from Demou and Hendrix.16

Functional Relevance of VM

The association of VM in patient tumors with a poor clinical outcome implies a functionally relevant advantage imparted by VM pertinent to the survival of the aggressive tumor cell phenotype. Experimental landmark studies have demonstrated a physiological perfusion of blood between endothelial-lined mouse vasculature and VM networks in human tumor xenografts, using Doppler imaging of circulating microbeads.19, 20 Additional findings from these studies elucidated the anticoagulant properties of tumor cells lining VM networks, facilitating the flow of blood in aggressive tumors. In this manner, VM can provide a functional perfusion pathway for rapidly growing tumors by transporting fluid from leaky vessels and/or connecting with endothelial-lined vasculature. A noteworthy example of VM functional plasticity and the importance of hypoxia as a catalyst of this phenotype was demonstrated with the transplantation of human metastatic melanoma cells into an ischemic mouse limb, which resulted in formation of a chimeric vasculature composed of human melanoma and mouse endothelial cells.21 After restoring blood flow to the limb, the melanoma cells formed a large tumor mass. This finding illustrates the remarkable influence of the microenvironment on the transendothelial differentiation of melanoma cells, which reverted to a more tumorigenic phenotype as the environmental cues changed.

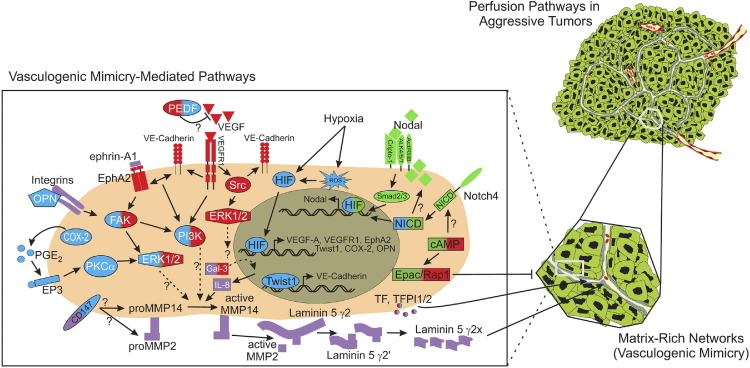

The functional plasticity associated with VM and the underlying multipotent tumor cell phenotype are supported by a complex integration of signaling pathways, which are typically restricted to events in embryonic development. In particular, essential VM modulating genes and proteins can be categorized into pathways associated with vascular, embryonic/stem cell, and hypoxia-related signaling.22 These pathways warrant rigorous scientific scrutiny as promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

Tumor Microenvironment

Studies in developmental biology and tumor progression have demonstrated that the extracellular microenvironment is not simply a passive structural element in which cells reside, but can also function as an interactive partner that is changed by, and can subsequently alter, cellular processes and responses. This dynamic reciprocity between tumor cells and their microenvironment plays an integral role in VM.

Microarray analyses of nonaggressive compared with highly aggressive melanoma cells revealed a differential expression pattern of candidate genes associated with the extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell-ECM interactions which could be involved in and facilitate VM (Table 1). Specifically, it was found that aggressive melanoma cells express significantly higher levels of the γ2 chain (compared with α3 or β3 chains) of the laminin 5 (laminin-332; Ln5) heterotrimeric basement membrane glycoprotein as well as matrix metalloproteinases MMP-1, -2, -9, and -14 [MMP-14 is also known as membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP)].7 Furthermore, Ln5 γ2 chain, MMP-2, and MMP-14 were found to colocalize with VM tubular networks formed in a three-dimensional type I collagen matrix by aggressive (but not nonaggressive) melanoma cells, and resembled laminin networks in patient tumor sections of aggressive melanoma (Figure 1), as well as in human melanoma xenografts in nude mice.

The structural integrity and perfusability of these tubular networks was demonstrated by injection of a fluorescent dye into the lumen of a tubule and by observation of the subsequent diffusion of the dye throughout the network (Figure 1). The increased expression and specific localization of these ECM components suggested that aggressive melanoma cells can modify their ECM to initiate and promote VM and led to a key observation, that collagen I three-dimensional matrices preconditioned by aggressive melanoma cells can induce nonaggressive melanoma cells and normal melanocytes (which do not express appreciable levels of Ln5 γ2 chain) to engage in VM in response to the Ln5 γ2 chain and its fragments deposited by the aggressive cells. Cleavage of Ln5 γ2 chain by MMP-14 or activated MMP-2 can generate fragments (γ2 and γ2′) that promote vigorous cell scattering, and it was also demonstrated that melanoma VM could be inhibited by blocking the expression of Ln5 γ2 chain with siRNA, or by treating the cells with a Ln5 function-blocking antibody or function-blocking antibodies to MMP-14 and MMP-2 to inhibit the generation of Ln5 γ2 chain fragments. Furthermore, nonaggressive melanoma cells could not initiate VM on an aggressive melanoma cell preconditioned matrix in the presence of a function-blocking antibody to the Ln5 γ2 chain. Collectively, these observations demonstrated the integral role that dynamic reciprocity plays between tumor cells and their microenvironment in VM, an understanding that may aid in development of targeted therapies directed at the ECM to alter tumor progression.

Vascular Signaling Pathways

The molecular dissection of the mechanisms involved in mediating VM began with microarray analyses of highly aggressive versus nonaggressive human melanoma cells. These data identified a molecular signature that revealed the complexity of the signal transduction pathways involved in this process.15, 23 Two of the first proteins identified to play a role in mediating melanoma VM were VE-cadherin, a cell-cell adhesion molecule associated with endothelial cells, and EPHA2, an epithelial cell-associated kinase involved in ephrin-A1-induced angiogenesis.24, 25 Studies designed to test the role of these proteins in promoting melanoma VM revealed that down-regulation of either VE-cadherin or EPHA2 inhibited VM. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that VE-cadherin could modulate the location and level of EPHA2 phosphorylation, providing the first evidence that signal transduction from the plasma membrane is necessary for melanoma VM.8 These pivotal experiments prompted additional studies, which revealed the importance of multiple cytoplasmic kinases involved in melanoma VM, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK).26, 27 Both PI3K and FAK were found to be phosphorylated downstream of EPHA2 and VE-cadherin, leading to increase in the activation of extracellular regulatory kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), up-regulation of MMP-14, and increase in MMP-2 activity and the subsequent cleavage of Ln5 γ2 chain into the γ2′ and γ2x fragments. Although the mechanism for increased expression of VE-cadherin or EPHA2 in human melanoma is not well understood, in hepatocellular carcinoma VE-cadherin expression is regulated by the transcription factor Twist 1 and contributes to VM.28

In recent years, many more studies linking various angiogenesis-promoting factors to VM have been published. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), a well-characterized promoter of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis, has been linked to VM in both melanoma and ovarian carcinoma. In melanoma, the autocrine secretion of VEGF-A is required for VM, largely through activation of VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1).29 Although activation of VEGFR1 leading to downstream activation of PI3K/AKT pathway is involved in endothelial cell-mediated angiogenesis, downstream activation of Src and ERK1/2 pathways promotes tumor cell invasion and migration.30 In the case of melanoma, VM appears to be mediated through the activation of PI3K/PKCα downstream of VEGFR1, in co-operation with integrin-mediated signaling pathways.29 Moreover, malignant melanoma initiating cells expressing the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) member ABCB5 display a plastic genotype and are able to engage in VM predominately through VEGFR1 mediated signal transduction pathways.31 Addition of VEGF-A to ovarian carcinoma cells promoted the up-regulation of VM-associated genes, including the genes for VE-cadherin, EPHA2, MMP-2, and MMP-9.32 These data suggest that VEGF-A can stimulate characteristics associated with tumor cell plasticity essential for VM. However, it has also been demonstrated that EPHA2 can mediate VEGF expression and VEGF-induced angiogenesis in mammary and pancreatic islet carcinoma cells, suggesting that, in some cases, EPHA2 may promote tumor cell plasticity.33

COX-2, an enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of arachidonic acid into primarily prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), has also been found to increase the expression of VEGF through a protein kinase C (PKC) mediated pathway. PGE2 binds to a family of prostanoid receptors (prostaglandin E2 receptor subtypes EP1, -2, -3, and -4), which in turn activate EGF receptor (EGFR) signaling, and PKC-dependent ERK1/2 activation.34 Signaling through these pathways promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and in some cases VM.34, 35, 36 A noninhibitory serpin, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF, encoded by SERPINF1), has been found to suppress angiogenesis through the inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR-1 signaling, induction of apoptosis, or promotion of tumor cell differentiation.37 PEDF may also inhibit VM, given that its expression is typically down-regulated in aggressive melanoma; moreover, inhibition of PEDF expression in nonaggressive melanoma cells induces VM.38

Tissue factor (TF) and TF pathway inhibitors TFPI-1 and TFPI-2 are important for the initiation and regulation of coagulation pathways, and all three have been found to be up-regulated in aggressive melanoma.20 The expression and activity of these proteins appear to contribute to the fluid-conducting properties of VM channels and are necessary for tubular network formation. Taken together, these data underscore the complexity and diversity of the signal transduction events that promote and regulate VM in various cancer types. A composite of known signal transduction events and pathways found to be involved in VM for various tumor types is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic model of signaling pathways implicated in tumor cell VM. Only signaling molecules that have been specifically modulated using antisense oligonucleotides, small inhibitory RNAs, blocking antibodies, small molecule inhibitors, or transient transfections, with demonstrated ability to directly affect VM, are depicted. These molecules are categorized as vascular (red), embryonic/stem cell (green), tumor microenvironment (purple), and hypoxia signaling pathways (blue). Molecules shaded with two different colors demonstrate overlap between major VM signaling pathways. Involvement of Gal-3, IL-8, cAMP, and EPAC 1/Rap1 in VM has been previously reviewed by Seftor et al.7 Question marks indicate the potential involvement of a protein and/or downstream effector protein or proteins in modulating VM in aggressive cancer cells, for which the underlying signaling pathway or pathways are not yet clearly defined. EP3, prostaglandin E receptor EP3 subtype (encoded by PTGER3).

Based on the model of Kirschmann et al.22

Stem Cell Signaling Pathways in VM

Defined pathways that regulate stem cell behavior and pluripotency also function in tumor cell plasticity and contribute to VM by aggressive tumor cells. Two pathways critical both for embryonic stem cell regulation and tumor cell behavior are the Notch and Nodal signaling pathways,39 and crosstalk between these pathways regulates tumor cell aggressiveness and VM network formation.40

Nodal signaling modulates vertebrate embryogenesis, functioning in embryonic stem cell pluripotency and in left-right asymmetry determination41; it is generally absent from adult tissues, but is reactivated in aggressive cancers.17, 42, 43 Nodal is a secreted growth factor and potent embryonic morphogen belonging to the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily; it activates signaling via binding to activin-like kinase receptors, type 1 (ALK4, -5, and -7) and type 2 (ACTR-IIB).41, 42 Nodal can signal with or without the coreceptor, cripto-1, to propagate downstream signaling through Smad2/3 and activate a transcriptional program typically including Nodal and its antagonist, Lefty. Particularly noteworthy, aggressive cancer cells reactivate Nodal, but not Lefty, whose promoter is heavily methylated.44 This lack of intrinsic regulatory control enables Nodal signaling to proceed unchecked and promotes aggressive tumor cell behavior and plasticity.17, 42, 43 Nodal mRNA is expressed in the melanoma cells contributing to VM structures,45 and Nodal protein is detected in a subpopulation of cultured melanoma and breast cancer cells.40, 46 Targeting ALK receptor activation with chemical inhibitors or Nodal with neutralizing antibodies reduced the ability of aggressive melanoma cancer cells to engage in VM on three-dimensional matrices.42, 47

The highly conserved Notch signaling pathway functions in stem cell differentiation and self-renewal in various niches of embryonic and adult tissues.48 Single transmembrane Notch receptors (Notch 1 to Notch 4) are typically activated by a membrane-tethered ligand (DLL1/2/4 or JAG1/2) on an adjacent cell, and binding triggers proteolytic cleavage events that release the Notch intracellular domain into the cytoplasm.39, 48 The Notch intracellular domain associates with a transcription factor complex to activate transcription of downstream target genes. During embryonic body plan establishment, Notch signaling regulates Nodal gene expression to direct left-right axis determination,49, 50 and this crosstalk between Notch and Nodal is recapitulated in melanoma, in which Notch 4 signaling controls Nodal gene expression to regulate tumor cell aggressiveness and plasticity, including VM.40 Notch 4 expression is enriched in melanoma VM networks,16 and targeting Notch 4 activity with function-blocking antibodies diminished VM formation in vitro, concomitant with a reduction in VE-cadherin expression.40 Importantly, VM network formation and VE-cadherin expression could be rescued by adding recombinant Nodal protein to the melanoma cell culture. Because VM may represent an alternative mechanism for tumor perfusion, targeting the Notch 4-Nodal signaling axis has potential for treatment strategies (Figure 3).

Hypoxia-Related Signaling Pathways

Hypoxia, either persistent or transient, is a hallmark of most solid tumors and can regulate pathways in cellular differentiation, induction/maintenance of stem cell-like characteristics, tumor progression, radio- and chemoresistance, angiogenesis, and VM, all of which are markers of poor prognosis in patients. The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) complex (comprised of HIF-1β and one HIF-α subunit: HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α) is a key regulator of oxygen homeostasis in both physiological and pathological environments. Under low oxygen availability, HIF-1α undergoes protein stabilization and translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to gene regulatory regions containing hypoxia response elements and activates transcription of hypoxia-target genes (reviewed by De Bock et al51 and by Benizri et al52). In particular, hypoxia and subsequent HIF overexpression in tumor cells induces the expression of gene products that are involved in angiogenesis (eg, VEGF), which is essential for cell viability, tumor growth, and metastasis. Recently, hypoxia has also been shown to induce VM in hepatocellular carcinoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and melanoma. In addition, hypoxia can induce a dedifferentiated phenotype in breast carcinoma.22

Pertinent to VM, hypoxia can directly modulate VEGF-A, VEGFR1, EPHA2, Twist, Nodal, osteopontin, and COX-2 gene expression (via HIF/hypoxia response element binding) or indirectly modulate VE-cadherin, TF, and PEDF expression (via activation of an intermediary protein that regulates gene transcription or posttranscriptional protein processing).53 In addition, hypoxia can modulate the expression of Notch-responsive genes via HIF-1α stabilization of the Notch intracellular domain protein and subsequent activation of genes with Notch-responsive promoters, including Nodal. This noncanonical crosstalk between HIF-1α and Notch signaling pathways is thought to promote an undifferentiated cell state, further illuminating the possible etiology of tumor cell plasticity underlying VM. Another mechanism by which hypoxia can promote VM is through the generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Redox-dependent stabilization of HIF-1α and induction of VM have been demonstrated in melanoma.29, 54 These studies demonstrating hypoxia-induced VM and VM-associated genes highlight the critical role for hypoxia in tumor progression (Figure 3). Indeed, treatment with some antiangiogenic agents, which inhibit tumor perfusion and increase intratumoral hypoxia, has demonstrated increased metastasis and VM.51, 55, 56

Translational Promise

VM has been reported across a broad range of solid tumors, and specifically in association with an aggressive and metastatic phenotype (reviewed by Paulis et al11). Establishing histopathology protocols for validating VM, however, has been hampered by the lack of universal markers. The earliest VM studies stained patient tissues with PAS (omitting hematoxylin counterstaining, to reduce visual noise) to outline the ECM networks, together with dual immunohistochemistry staining for a tumor-specific marker (such as HMB-45 for melanoma) plus a vascular marker (such as VE-cadherin or TIE1), with final validation by transmission electron microscopic evidence of tumor cell-lined channels containing red blood cells.1 This approach was cumbersome to deploy and difficult to replicate consistently across laboratories. Better recognition of tumor cell VM has evolved, based on the results of molecular studies indicating a plastic, stem cell-like phenotype underlying VM. Most noteworthy is the observation that tumor cells engaged in VM can express ABCB5 (a chemoresistance gene), which coincides with a malignant melanoma-initiating subpopulation,31 a finding that underscores the importance of identifying VM targets to effectively treat aggressive tumors. Collectively, these studies can guide pathologists to identify VM in patient tissues as an indicator of an aggressive tumor cell phenotype and as a predictor of chemoresponsiveness and, ultimately, disease outcome. Nonetheless, further validation of specific VM markers across various cancers is necessary before VM analysis can be accepted as an integral part of histopathology reports.

Although the use of antiangiogenic compounds to target the blood supply of a tumor seems logical, the success of these compounds in the clinic has thus far been very limited. Bevacizumab, sorafenib, and sunitinib have all been used clinically to treat various cancers, with limited efficacy. Clinical use of these drugs has been shown to limit the growth of the primary tumor, but long-lasting effects are rare and typically lead to only moderate benefits for overall survival.57 In breast cancer, the preclinical and clinical results are likely due to the development of a hypoxic microenvironment within the tumor leading to the proliferation of cancer stem cells, a cell type with the greatest degree of plasticity and ability to metastasize.58 Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that a hypoxic microenvironment within a tumor may promote the development of tumor-derived endothelial cells in glioblastoma.59 Although these tumor-derived endothelial cells still express tumor-specific markers, they are otherwise indistinguishable from conventional endothelial cells. Interestingly, although the differentiation of glioblastoma cells into endothelial cells requires a hypoxic microenvironment, the mechanism was reported to be independent of VEGF-mediated or FGF-mediated signaling.59 Taken together, these data underscore the need for the continued development of treatment strategies that target the plastic phenotype and microenvironment of aggressive tumor cells.

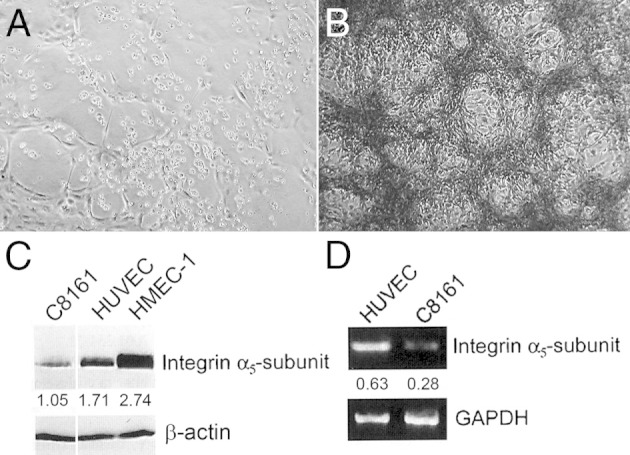

Considering the diverse nature of vascular perfusion pathways in tumors, it may be prudent to test the efficacy of currently available angiogenesis inhibitors on tumor cell VM, in addition to endothelial cell-driven angiogenesis (Table 2). For example, curcumin, imatinib, and thalidomide have all been shown to inhibit melanoma VM, concomitant with decreases in EPHA2, VE-cadherin, PI3K, VEGF, HIF-1α, MMP-2, and MMP-9 expression and/or activity, suggesting that these compounds can affect several different aspects of the signaling mechanisms mediating VM.61, 63, 65 ASA404 (DMZAA), a small molecule vascular disrupting agent, was found to inhibit melanoma VM through a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism.67 Isoxanthohumol, an inhibitor of TGF-β inducible genes related to angiogenesis and metastasis, was able to block VM in breast cancer cells.66 Rapamycin (sirolimus), an inhibitor of mTOR and HIF-1α, was able to prevent VM in ovarian cancer through the down-regulation of CD31 and factor VIII.64 By contrast, endostatin is ineffective in inhibiting melanoma VM, largely because these tumor cells lack the appropriate target receptors for an effective response62 (Figure 4). Interestingly, Endostar, a novel recombinant form of human endostatin, has shown limited ability inhibiting VM in glioblastoma in vitro (although the mechanism for this biological effect remains unknown).63

Table 2.

Angiogenesis Inhibitors and Effect on VM

| Therapeutic agents⁎ | Molecular target or function | Effect on VM | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies | |||

| bevacizumab (Avastin) | VEGF | no effect | Wang et al14 |

| cetuximab (Erbitux) | EGFR | ND | |

| panitumumab (Vectibix) | EGFR | ND | |

| Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors | |||

| sunitinib (Sutent) | VEGFRs, PDGFR-β, RET | ND | |

| sorafenib (Nexavar) | VEGFRs, PDGFR-β, Raf-1 | ND | |

| erlotinib (Tarceva) | EGFR | ND | |

| imatinib (Gleevec, Glivec) | TK inhibition; BCR-ABL | inhibition | Paulis et al60 |

| gefitinib (Iressa) | EGFR | ND | |

| pazopanib (Votrient, GW786034) | VEGFRs, PDGFR-β, c-Kit | ND | |

| lapatinib (Tykerb) | EGFR, HER2 | ND | |

| Other antiangiogenic agents and angiogenesis inhibitors | |||

| thalidomide (Thalomid) | TNFα; ROS producer | inhibition | Zhang et al61 |

| TNP-470 (AGM-1470) | TK inhibition | no effect | van der Schaft et al62 |

| endostatin (rhEndostatin, Endostar) | integrin signaling | no effect | van der Schaft et al62; Liu et al63 |

| sirolimus† (Rapamune) | mTOR, VEGF | inhibition | Su et al64 |

| curcumin | EPHA2, PI3K, MMPs | inhibition | Chen et al65 |

| isoxanthohumol | TGF-β signaling | inhibition | Serwe et al66 |

| vadimezan (ASA404, AS1404, DMXAA) | MAPK, VE-cadherin | inhibition | Zhao et al67 |

| resveratrol | VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | inhibition | Vartanian et al29 |

ND, not determined; VM, vasculogenic mimicry.

Generic and INN names are given first, with applicable trade name, code name, or abbreviation in parenthesis.

Sirolimus is also known as rapamycin.

Figure 4.

Endostatin disrupts angiogenesis but not VM. A: Bright-field micrograph of human microvascular endothelial cells-1 (HMEC-1) cultured on a three-dimensional collagen I gel for 3 days in the presence of 10 μg/mL of recombinant human (rh) endostatin. B: Bright-field micrograph of PAS-stained aggressive human melanoma cells cultured on a three-dimensional collagen I gel for 6 days in the presence of 10 μg/mL of recombinant human endostatin. C: Western blot analysis shows the relative differences among endostatin receptor α5-integrin subunit protein expression levels in whole-cell lysates from aggressive human melanoma cells (C8161), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and HMEC-1 cells. β-Actin was used as a control for equal loading, and protein amounts were determined relative to β-actin. D: Semiquantitative RT-PCR shows the relative expression levels of integrin α5 subunit mRNA in C8161, HUVEC, and HMEC-1 cells. GAPDH was used as a control for both loading and relative levels of expression. Original magnification: ×100.

Reproduced with permission from Hendrix et al5 (A and B) and from van der Schaft et al62 (C and D).

It seems plausible that the most efficient way to target tumor cell plasticity is to inhibit multiple signaling pathways simultaneously. For example, for the non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line MV-522, treatment with anti-VEGF antibodies in conjunction with anti-delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) antibodies resulted in the greatest inhibition of tumor growth in mice over a period of 35 days.68 Similar results were demonstrated in glioblastoma, in which ectopic expression of Dll4 could impart resistance to bevacizumab in vivo; however, this resistance could be reversed when tumor xenografts were concomitantly treated with dibenzazepine.69 Moreover, bevacizumab had no effect on the ability of a subpopulation of CD133+ glioblastoma cells to differentiate into endothelial progenitor cells; however, this transition could be blocked through inhibition of γ-secretase or Notch 1 silencing.14

Considering future development of new treatment strategies, it is evident that suppression of master plasticity pathways associated with promoting VM, increased tumorigenicity, and stemness of tumor cell populations has resulted in substantial inhibition of tumor progression. Moreover, VM is considered a reliable predictor of clinical outcome for various cancer types.22 Identification of VM within patient samples may serve in a new classification scheme based on tumor cell plasticity, thus identifying cases requiring an aggressive treatment strategy consisting of combinatorial targets (Figure 3).

Concluding Remarks

The foundational studies underlying tumor cell VM and the transendothelial differentiation of tumor cells illuminate the importance of achieving a better understanding of the molecular pathways governing tumor cell plasticity. Given the findings that aggressive tumor cells express endothelial markers, it is critical that the appropriate reagents are used to unequivocally distinguish tumor cells from endothelial cells. Although a great deal of controversy erupted over the initial VM reports, these criticisms compelled more rigorous scientific scrutiny of the new VM paradigm. Ultimately, the emerging discoveries surrounding VM are leading to more accurate histopathology interpretations and novel cancer therapies directed toward combinatorial targets.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Robert Folberg, Andrew Maniotis, Anil Sood, Daisy van der Schaft, Arjan Griffioen, Zoe Demou, Paul Meltzer, Jeffrey Trent, Vito Quaranta, Wolfram Ruf, and Lynne-Marie Postovit for their critical contributions.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH NCI R03-CA83137 to R.E.B.S. and R37-CA59702, R01-CA121205, R01-CA80318, R01-CA88043, and U54-CA143869 to M.J.C.H.).

R.E.B.S. and A.R.H. contributed equally to this work.

M.J.C.H. was Associate Editor of The American Journal of Pathology from 2004 to 2008.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.013.

References

- 1.Maniotis A.J., Folberg R., Hess A., Seftor E.A., Gardner L.M.G., Pe'er J., Trent J.M., Meltzer P.S., Hendrix M.J.C. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:739–752. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bissell M.J. Tumor plasticity allows vasculogenic mimicry, a novel form of angiogenic switch: A rose by any other name? Am J Pathol. 1999;155:675–679. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barinaga M. New type of blood vessel found in tumors. Science. 1999;285:1475. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald D.M., Munn L., Jain R.K. Vasculogenic mimicry: how convincing, how novel, and how significant. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrix M.J.C., Seftor E.A., Hess A.R., Seftor R.E.B. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sood A.K., Seftor E.A., Fletcher M.S., Gardner L.M.G., Heidger P.M., Butler R.E., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Molecular determinants of ovarian cancer plasticity. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seftor R.E.B., Seftor E.A., Koshikawa N., Meltzer P.S., Gardner L.M.G., Bilban M., Stetler-Stevenson W.G., Quaranta V., Hendrix M.J.C. Cooperative interactions of laminin 5 gamma2 chain, matrix metalloproteinase-2, and membrane type-1-matrix/metalloproteinase are required for mimicry of embryonic vasculogenesis by aggressive melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6322–6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess A.R., Seftor E.A., Gruman L.M., Kinch M.S., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. VE-cadherin regulates EphA2 in aggressive melanoma cells through a novel signaling pathway: implications for vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:228–233. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.2.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren B.A., Shubik P. The growth of the blood supply to melanoma transplants in the hamster cheek pouch. Lab Invest. 1966;15:464–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damsky C.H., Fisher S.J. Trophoblast pseudo-vasculogenesis: faking it with endothelial adhesion receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:660–666. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulis Y.W.J., Soetekouw P.M., Verheul H.M.W., Tjan-Heijnen V.C.G., Griffioen A.W. Signalling pathways in vasculogenic mimicry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Döme B., Hendrix M.J.C., Paku S., Tovari J., Timar J. Alternative vascularization mechanisms in cancer: pathology and therapeutic implications. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1–15. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci-Vitiani L., Pallini R., Biffoni M., Todaro M., Invernici G., Cenci T., Maira G., Parati E.A., Stassi G., Larocca L.M., De Maria R. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells [Erratum appeared in Nature 2011, 477:238, and in Nature 2011, 469:432] Nature. 2010;468:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R., Chadalavada K., Wilshire J., Kowalik U., Hovinga K.E., Gever A., Fligelman B., Leversha M., Brennan C., Tabar V. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner M., Meltzer P., Chen Y., Jiang Y., Seftor E.A., Hendrix M.J.C., Radmacher M., Simon R., Yakhini Z., Ben-Dor A., Sampas N., Dougherty E., Wang E., Marincola F., Gooden C., Lueders J., Glatfelter A., Pollock P., Carpten J., Gillanders E., Leja D., Dietrich K., Beaudry C., Berens M., Alberts D., Sondak V. Molecular classification of cutaneous malignant melanoma by gene expression: shifting from a continuous spectrum to distinct biologic entries. Nature. 2000;406:536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demou Z., Hendrix M.J.C. Microgenomics profile of the endogenous angiogenic phenotype in subpopulations of aggressive melanoma. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:562–573. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postovit L.M., Margaryan N.V., Seftor E.A., Kirschmann D.A., Lipavsky A., Wheaton W.W., Abbott D.E., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4329–4334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihic-Probst D., Ikenberg K., Tinguely M., Schrami P., Behnke S., Seifert B., Civenni G., Sommer L., Moch H., Dummer R. Tumor cell plasticity and angiogenesis in human melanoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrix M.J.C., Seftor E.A., Meltzer P.S., Hess A.R., Gruman L.M., Nickoloff B.J., Miele L., Sheriff D.D., Schatteman G.C., Bourdon M.A., Seftor R.E.B. The stem cell plasticity of aggressive melanoma tumor cells. In: Sell S., editor. Stem Cells Handbook. Humana Press; Totowa NJ: 2000. pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruf W., Seftor E.A., Petrovan R.J., Weiss R.M., Gruman L.M., Margaryan N.V., Seftor R.E.B., Miyagi Y., Hendrix M.J.C. Differential role of tissue factor pathway inhibitors 1 and 2 (TFPI-1 and 2) in melanoma vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5381–5389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix M.J.C., Seftor R.E.B., Seftor E.A., Gruman L.M., Lee L.M., Nickoloff B.J., Miele L., Sheriff D.D., Schatteman G.C. Transendothelial function of human metastatic melanoma cells: role of the microenvironment in cell-fate determination. Cancer Res. 2002;62:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirschmann D.A., Seftor E.A., Hardy K.M., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Molecular pathways: vasculogenic mimicry in tumor cells: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2726–2732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seftor E.A., Meltzer P.S., Schatteman G.C., Gruman L.M., Hess A.R., Kirschmann D.A., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Expression of multiple molecular phenotypes by aggressive melanoma tumor cells: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrix M.J.C., Seftor E.A., Meltzer P.S., Gardner L.M., Hess A.R., Kirschmann D.A., Schatteman G.C., Seftor R.E.B. Expression and functional significance of VE-cadherin in aggressive human melanoma cells: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8018–8023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131209798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess A.R., Seftor E.A., Gardner L.M., Carles-Kinch K., Schneider G.B., Seftor R.E.B., Kinch M.S., Hendrix M.J.C. Molecular regulation of tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry by tyrosine phosphorylation: role of epithelial cell kinase (Eck/EphA2) Cancer Res. 2001;61:3250–3255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hess A.R., Hendrix M.J.C. Focal adhesion kinase signaling and the aggressive melanoma phenotype. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:478–480. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess A.R., Seftor E.A., Seftor R.E.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and MMP-2 activity during melanoma cell vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4757–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun T., Zhao N., Zhao X.L., Gu Q., Zhang S.W., Che N., Wang X.H., Du J., Liu Y.X., Sun B.C. Expression and functional significance of Twist1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: its role in vasculogenic mimicry. Hepatology. 2010;51:545–556. doi: 10.1002/hep.23311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vartanian A., Stepanova E., Grigorieva I., Solomko E., Baryshnikov A., Lichinitser M. VEGFR1 and PKCalpha signaling control melanoma vasculogenic mimicry in a VEGFR2 kinase-independent manner. Melanoma Res. 2011;21:91–98. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328343a237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch S., Tugues S., Li X., Gualandi L., Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem J. 2011;437:169–183. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank N.Y., Schatton T., Kim S., Zhan Q., Wilson B.J., Ma J., Saab K.R., Osherov V., Widlund H.R., Gasser M., Waaga-Gasser A.M., Kupper T.S., Murphy G.F., Frank M.H. VEGFR-1 expressed by malignant melanoma-initiating cells is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1474–1485. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J.Y., Sun T., Zhao X.L., Zhang S.W., Zhang D.F., Gu Q., Wang X.H., Zhao N., Qie S., Sun B.C. Functional significance of VEGF-A in human ovarian carcinoma: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:758–766. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.5.5765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng N., Brantley D., Fang W.B., Liu H., Fanslow W., Cerretti D.P., Bussell K.N., Reith A., Jackson D., Chen J. Inhibition of VEGF-dependent multistage carcinogenesis by soluble EphA receptors. Neoplasia. 2003;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu W.K., Sung J.J., Lee C.W., Yu J., Cho C.H. Cyclooxygenase-2 in tumorigenesis of gastrointestinal cancers: an update on the molecular mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2010;295:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basu G.D., Liang W.S., Stephan D.A., Wegener L.T., Conley C.R., Pockaj B.A., Mukherjee P. A novel role for cyclooxygenase-2 in regulating vascular channel formation by human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R69. doi: 10.1186/bcr1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson F.M., Simeone A.M., Lucci A., McMurray J.S., Ghosh S., Cristofanilli M. Differential regulation of the aggressive phenotype of inflammatory breast cancer cells by prostanoid receptors EP3 and EP4. Cancer. 2010;116(11 Suppl):2806–2814. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoshina D., Abe R., Yamagishi S.I., Shimizu H. The role of PEDF in tumor growth and metastasis. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:292–295. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orgaz J.L., Ladhani O., Hoek K.S., Fernández-Barral A., Mihic D., Aguilera O., Seftor E.A., Bernad A., Rodríguez-Peralto J.L., Hendrix M.J., Volpert O.V., Jiménez B. Loss of pigment epithelium-derived factor enables migration, invasion and metastatic spread of human melanoma. Oncogene. 2009;28:4147–4161. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strizzi L., Hardy K.M., Seftor E.A., Costa F.F., Kirschmann D.A., Seftor R.E.B., Postovit L.M., Hendrix M.J.C. Development and cancer: at the crossroads of Nodal and Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7131–7134. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1199. [Erratum appeared in Cancer Res 2009, 69:8526–7] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardy K.M., Kirschmann D.A., Seftor E.A., Margaryan N.V., Postovit L.M., Strizzi L., Hendrix M.J.C. Regulation of the embryonic morphogen Nodal by Notch4 facilitates manifestation of the aggressive melanoma phenotype. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10340–10350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schier A.F. Nodal signaling in vertebrate development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:589–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.041603.094522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Topczewska J.M., Postovit L.M., Margaryan N.V., Sam A., Hess A.R., Wheaton W.W., Nickoloff B.J., Topczewski J., Hendrix M.J.C. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 2006;12:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strizzi L., Hardy K.M., Kirschmann D.A., Ahrlund-Richter L., Hendrix M.J.C. Nodal expression and detection in cancer: experience and challenges. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1915–1920. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa F.F., Seftor E.A., Bischof J.M., Kirschmann D.A., Strizzi L., Arndt K., Bonaldo Mde F., Soares M.B., Hendrix M.J.C. Epigenetically reprogramming metastatic tumor cells with an embryonic microenvironment. Epigenomics. 2009;1:387–398. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McAllister J.C., Zhan Q., Weishaupt C., Hsu M.Y., Murphy G.F. The embryonic morphogen, Nodal, is associated with channel-like structures in human malignant melanoma xenografts. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(Suppl 1):19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strizzi L., Hardy K.M., Margaryan N.V., Hillman D.W., Seftor E.A., Chen B., Geiger X.J., Thompson E.A., Lingle W.L., Andorfer C.A., Perez E.A., Hendrix M.J.C. Potential for the embryonic morphogen Nodal as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R75. doi: 10.1186/bcr3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strizzi L., Postovit L.M., Margaryan N.V., Lipavsky A., Gadiot J., Blank C., Seftor R.E.B., Seftor E.A., Hendrix M.J.C. Nodal as a biomarker for melanoma progression and a new therapeutic target for clinical intervention. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009;4:67–78. doi: 10.1586/17469872.4.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J., Sato C., Cerletti M., Wagers A. Notch signaling in the regulation of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:367–409. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebs L.T., Iwai N., Nonaka S., Welsh I.C., Lan Y., Jiang R., Saijoh Y., O'Brien T.P., Hamada H., Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates left-right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1207–1212. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raya A., Kawakami Y., Rodriguez-Esteban C., Buscher D., Koth C.M., Itoh T., Morita M., Raya R.M., Dubova I., Bessa J.G., de la Pompa J.L., Izpisua Belmonte J.C. Notch activity induces Nodal expression and mediates the establishment of left-right asymmetry in vertebrate embryos. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1213–1218. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Bock K., Mazzone M., Carmeliet P. Antiantiogenic therapy, hypoxia, and metastasis: risky liaisons, or not. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:393–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benizri E., Ginouvès A., Berra E. The magic of the hypoxia-signaling cascade. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1133–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernández-Barral A., Orgaz J.L., Gomez V., del Peso L., Calzada M.J., Jiménez B. Hypoxia negatively regulates antimetastatic PEDF in melanoma cells by a hypoxia inducible factor-independent, autophagy dependent mechanisms. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Comito G., Calvani M., Giannoni E., Bianchini R., Calorini L., Torre E., Migliore C., Giordano S., Chiarugi P. HIF-1α stailization by mitochondrial ROS promotes Met-dependent invasive growth and vasculogenic mimicry in melanoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Y., Li Q., Li X.Y., Yang Q.Y., Xu W.W., Liu G.L. Short-term anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment elicits vasculogenic mimicry formation of tumors to accelerate metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebos J.M., Lee C.R., Cruz-Munoz W., Bjarnason G.A., Christensen J.G., Kerbel R.S. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergers G., Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conley S.J., Gheordunescu E., Kakarala P., Newman B., Korkaya H., Heath A.N., Clouthier S.G., Wicha M.S. Antiangiogenic agents increase breast cancer stem cells via the generation of tumor hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2784–2789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018866109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soda Y., Marumoto T., Friedmann-Morvinski D., Soda M., Liu F., Michiue H., Pastorino S., Yang M., Hoffman R.M., Kesari S., Verma I.M. Transdifferentiation of glioblastoma cells into vascular endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4274–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paulis Y.W.J., Dinnes D., Soetekouw P.M.M.B., Nelson P.J., Burdach S., Loewe R.P., Tjan-Heijnen V.C.G., Luettichau I.V., Griffioen A.W. Imatinib reduces the vasculogenic potential of plastic tumor cells. Current Angiogenesis. 2012;1:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang S., Li M., Gu Y., Liu Z., Xu S., Cui Y., Sun B. Thalidomide influences growth and vasculogenic mimicry channel formation in melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:60. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Schaft D.W., Seftor R.E.B., Seftor E.A., Hess A.R., Gruman L.M., Kirschmann D.A., Yokoyama Y., Griffioen A.W., Hendrix M.J.C. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on vascular network formation by human endothelial and melanoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1473–1477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Z., Li Y., Zhao W., Ma Y., Yang X. Demonstration of vasculogenic mimicry in astrocytomas and effects of Endostar on U251 cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su M., Feng Y.J., Yao L.Q., Cheng M.J., Xu C.J., Huang Y., Zhao Y.Q., Jiang H. Plasticity of ovarian cancer cell SKOV3ip and vasculogenic mimicry in vivo. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:476–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen L.X., He Y.J., Zhao S.Z., Wu J.G., Wang J.T., Zhu L.M., Lin T.T., Sun B.C., Li X.R. Inhibition of tumor growth and vasculogenic mimicry by curcumin through down-regulation of the EphA2/PI3K/MMP pathway in a murine choroidal melanoma model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:229–235. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Serwe A., Rudolph K., Anke T., Erkel G. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling, vasculogenic mimicry and proinflammatory gene expression by isoxanthohumol. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:898–915. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao L., Marshall E.S., Kelland L.R., Baguley B.C. Evidence for the involvement of p38 MAP kinase in the action of the vascular disrupting agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ridgway J., Zhang G., Wu Y., Stawicki S., Liang W.C., Chanthery Y., Kowalski J., Watts R.J., Callahan C., Kasman I., Singh M., Chien M., Tan C., Hongo J.A., de Sauvage F., Plowman G., Yan M. Inhibition of Dll4 signalling inhibits tumour growth by deregulating angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444:1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/nature05313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J.L., Sainson R.C., Oon C.E., Turley H., Leek R., Sheldon H., Bridges E., Shi W., Snell C., Bowden E.T., Wu H., Chowdhury P.S., Russell A.J., Montgomery C.P., Poulsom R., Harris A.L. DLL4-Notch signaling mediates tumor resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in vivo. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6073–6083. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]