Abstract

Background:

Candida parapsilosis is an emergent agent of invasive fungal infections. This yeast is one of the five most widespread yeasts concerned in invasive candidiasis.

C. parapsilosis stands out as the second most common yeast species isolated from patients with bloodstream infections especially in neonates with catheter.

Recently several reports suggested that its reduced susceptibility to azoles and polyene might become a cause for clinical concern, although C. parapsilosis is not believed to be intensely prone to the development of antifungal resistance.

Methods:

In the present report, One hundred and twenty clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis complex were identified and differentiated by using PCR-RFLP analysis. The isolates were then analyzed to determine their susceptibility profile to fluconazole (FLU), itraconazole (ITC) and amphotericin B. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results were analyzed according to the standard CLSI guide.

Results:

All of isolates were identified as C. parapsilosis. No C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis strains were found. Evaluation of the antifungal susceptibility profile showed that only three (2.5%) C. parapsilosis were resistant to fluconazole, three (2.5%) C. parapsilosis were resistant to itraconazole and two (1.7%) C. parapsilosis were amphotericin B resistant.

Conclusion:

Profiles in clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis can provide important information for the control of antifungal resistance as well as distribution and susceptibility profiles in populations.

Keywords: Candida parapsilosis, Antifungal susceptibility, Resistant, Iran

Introduction

Candidiasis is caused by Candida species that can produce a broad spectrum of human infections (1). Candida parapsilosis is among the most common yeasts concerning invasive candidiasis. C. parapsilosis is the most common non-albicans Candida species, frequently isolated from individuals with damaged immune systems and from pediatric units. Recently, the incidence of invasive candidiasis due to C. parapsilosis has been increased (2). The high affinity of C. parapsilosis for intravascular devices may lead to exogenous candidemia due to contamination of such devices or because of biofilm (3–9).

The pathogen is also able to form biofilms on other medical surface such as implants. Based on new taxonomic concepts, C. parapsilosis is a complex consists of C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis in which C. parapsilosis are mentioned as the predominant species isolated from clinical samples (10, 11).

Azole antifungals including fluconazole, itraconazole, and miconazole and polyene antibiotics such as amphotericin B and nystatin are commonly drugs used for treatment of candidiasis in forms of topical, oral or intravenous. Fluconazole has been widely used for the treatment of systemic candidiasis (12). These medicines are indicated to inhibit the activity of lanosterol demethylase enzyme, which involved in the biosynthesis of ergosterol in fungal cells (13). However, several recent studies have revealed an increasing resistance to this antifungal.

Although in comparison to other Candida species, there is little information on antifungal resistance in C. parapsilosis, evidences have indicated that this pathogenic yeast is prone for development of drug resistance and the frequency of such resistances may differ by geographic region (14).

Antifungal agents prevent from infections caused by Candida in high-risk patients but the increasing use of antifungals might also have changes in the species causing infections. The hands of healthcare workers may be the main environmental source that in nosocomial outbreaks of C. parapsilosis have also been described formerly (10).

Few studies have informed about antifungal susceptibility profile of C. parapsilosis in Iran. Moreover, the definition of the antifungal susceptibility profile of C. parapsilosis is significant for clinical. The differences in susceptibility this species between antifungal agents may influence the therapeutic choices. Because of this change and the importance of C. parapsilosis in Iran, we surveyed the susceptibilities of such isolates to three commonly used antifungal agents, namely, FLU, ITC and AMB.

Materials and Methods

Clinical isolates

A total of 120 isolates of C. parapsilosis already collected and diagnosed from clinical samples during an epidemiological study in Tehran, Isfahan, Mazandaran, and Alborz provinces between 2009 to 2013 (1), were used in this study.

All isolates were sub-cultured on CHROMagar Candida medium (CHROMagar Microbiology, Paris, France), incubated at 35 °C for 48 h and production of specific colony colors were analyzed for preliminary species identification.

DNA extraction

The isolated yeasts were sub-cultured on sabouraud dextrose agar (Merck, Germany) at 32 °C for 48 h. Genomic DNA was extracted from harvested yeasts grown in a broth comprised of 2% glucose, 1% yeast extract (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and 2% pepton (Oxoid). Briefly, yeast cells were harvested and lysed adding 0.3 g of glass beads (diameter, 0.45 to 0.52 mm; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 300 μl of DNA lysis buffer (100mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2% Triton X-100, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1mM EDTA), and 300 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (PCI) (25:24:1). The mixture was then vortexed for 30 sec and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, 300 μl of chloroform was added, and vortexed for few seconds and centrifuged again; then 250 μl of ethanol and 25 μl of 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) were added to the obtained supernatant and incubated for 10 min at −20°C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 12 min and the pellet was re-suspended in 100 μl distilled water as purified DNA and stored at −20 °C until used (15).

Species confirmation

In order to confirmation of the already identified C. parapsilosis isolates and for molecular differentiation of C. parapsilosis from C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis, PCR-RFLP was performed as described previously (1, 11, 16, 2). Briefly, PCR mixture containing 5 μl of 10× reaction buffer, 1mM dNTPs, 1mM MgCl, 1U of DNA Taq polymerase, 2μl of each ITS1 (5 ′ -TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3 ′), ITS4 (5 ′ -TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3 ′) primers, or 2μl of each SADHF (5 ′ -GTT GAT GCT GTT GGA TTGT-3 ′), SADHR (5 ′ -CAA TGC CAA ATC TCC CAA-3 ′) primers (10, 15), and 3 μl of extracted DNA in a final volume of 50 μl, were used.

Conditions for PCR in thermal cycler machine were as follows: initial DNA denaturation at 95° C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min and final extension step at 72°C for 10 min.

RFLP mixture contained 10μl of PCR product, 2μl of the supplied buffer, 1U of NlaIII and/or MspI enzymes, and 18μl of nuclease-free distill water.

Five μl of PCR product and 15 μl of each RFLP products were fractionated by electrophoresis on respectively 1% and 2% agarose gel and stained with 0.5μg/ml ethidium bromide. The species of C. parapsilosis was confirmed or identified according to already published electrophoresis patterns (1, 2).

Antifungals

Standard fluconazole (FLC) (Tehran Daru, IRAN), amphotericin B (AMB) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), itraconazole (ITC) (Tehran Daru, IRAN) were used for preparation of tock solutions. FLC was prepared in distilled water while AMB and ITC in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The solutions were then kept frozen at −70 °C until use. Dilution of antifungal was performed with RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, GIBCO) and buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholine propane sulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (Sigma, USA) (10).

Antifungal susceptibility analysis

Antifungal susceptibility tests were performed by broth micro dilution method as described in Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, document M27-S3 (17).

C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019-type strain was used for quality control in all antifungal susceptibility tests.

Tests were performed in 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates.

Cell suspensions were prepared in RPMI 1640 medium and were adjusted to give a final inoculum concentration of about 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 cells/ml. The plates were incubated at 35 °C and were observed after 48 h. minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) were then determined and compared with drug-free control. All tests were performed in duplicate. The MIC results were analyzed according to the M27-S3 supplement of the CLSI Guide.

The interpretive criteria for susceptibility to antifungal drugs were based on CLSI (17).

Results

One hundred and twenty clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis were studied. These isolates which had been collected during epidemiological studies and diagnosed as C. parapsilosis previously, were obtained from 120 patients (65% females and 35% males). Based on the age, the patients ranged from 6 to 81 yr with a mean age of 42.4 yr. The location and gender of these clinical isolates are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1:

C. Parapsilosis isolates according to gender and location

| Location | Gender | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Nail | 66 | 55 | 22 | 18.3 | 88 | 73.33 |

| Groin | 2 | 1.7 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 6.7 |

| Interdigital | 2 | 1.7 | 9 | 7.5 | 11 | 9.2 |

| Vaginitis | 3 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Hand | 2 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.6 | 4 | 3.3 |

| Others (sputum,ear discharge) | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 6 | 5 |

| Total | 78 | 65.1 | 42 | 34.9 | 120 | 100 |

RFLP analysis

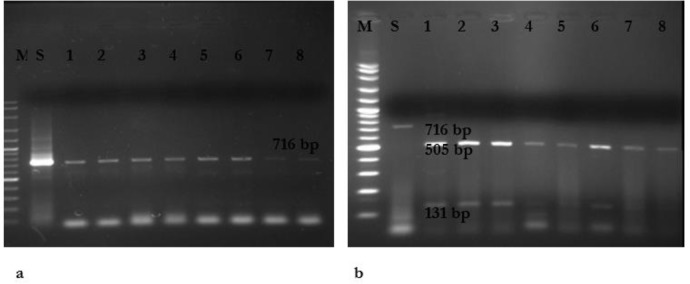

PCR using the primers ITS1 and 4 followed by restriction digestion with MspI indicated a restriction map which meets the restriction characteristics of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (data not shown). In addition, amplification of SADH gene revealed a single band with approximate size of 716bp in all isolates (Fig 1.A). Amplification and subsequent digestion of the SADH gene with NlaIII (Hin1II) in 120 strains C. parapsilosis complex produced fragments with the sizes 131 and 505bp. No C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis strains were found (Fig. 1.B).

Fig. 1:

a) Agarose gel electrophoresis of SADH-PCR products of C. parapsilosis complex. Lane M is 100 bp DNA size marker, Lane1(S) is C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, lanes 2– 8 are C. parapsilosis clinical isolates. b) RFLP-PCR products of C. Parapsilosis after digestion with NlaIII. Lane M is 100 bp DNA size marker, lane 1 is C. Parapsilosis ATCC 22019 without effect enzyme (716 bp), Lanes 2-8 are C. Parapsilosis (131 and 505 bp).

Antifungal susceptibility

The results of antifungal susceptibility analysis are described in Table 2. Two, three and three isolates were found as the strains resistant AMB, FLC, and ITC, respectively.

Table 2:

The results of antifungal susceptibility of clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis used in this study

| Antifungal Agent | Susceptible* MIC (mg/ml) | Susceptible Dose dependent* MIC (mg/ml) | Resistant* MIC (mg/ml) | Number of tested isolates | Number of resistant isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | ≤0.125 | 0.25–0.5 | ≥1 | 120 | 2 (≥1) |

| Fluconazole | ≤8 | 16–32 | ≥64 | 120 | 3 (>64) |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.125 | 0.25–0.5 | ≥1 | 120 | 3 (>1) |

Table 2 summarizes the in vitro susceptibilities of the 120 isolates to the three antifungal drugs as measured by the reference broth micro dilution method. The data are reported as MIC ranges of the isolates are inhibited.

Of the 120 isolates tested, for two isolates the broth microdilution MICs were ≥1mg/ml for amphotericin B and for 3 isolates the fluconazole MICs were ≥64 mg/ml, for 3 isolates the itraconazole MICs were ≥1mg/ml. Numbers of susceptible, susceptible in a dose-dependent manner and resistant isolates are shown in this chart. Surprisingly, all eight resistant species were isolated from the patients with nails infection.

Discussion

C. parapsilosis is the second common species isolated from patients with candidemia (4, 18, 19). The prevalence of fungemia due to this fungus has changed over the years and has been reported frequently in blood stream infections especially in neonates with catheter. The reasons for the rising incidence of C. parapsilosis candidemia are not completely known, although catheters and parenteral nutrition have been known as specific risk factors (4–7, 9, 18, 20–22).

The source of most occurrences of C. parapsilosis fungemia is a vascular catheter and these commonly progress in patients who had formerly received antifungal treatment. Therefore, the administration of the antifungal agents should be combined with the quick removal of the catheter to obtain an acceptable response to FLU or to any other antifungal (10).

C. parapsilosis can be part of the normal flora of the human skin, appearing to be directly presented into the bloodstream and is often associated to an exogenous source (hands of healthcare providers). BSIs caused by C. parapsilosis are not commonly related with previous colonization. However, infections caused by C. albicans frequently result from endogenous sources (commonly colonizing the genital mucosae and gastrointestinal) (5, 6, 9).

In comparison with risk factors related of C. albicans, these in C. parapsilosis fungemia were transplant recipients, patients who got previous antifungal therapy and especially in neonates who received parenteral nutrition. Rate of mortality reported with C. parapsilosis fungemia is very low (4).

We evaluated the in vitro activities of FLC, ITC, and AMB against C. parapsilosis. According to the results of Mirhendi et al (2), we analyzed the restriction polymorphism of the SADH gene and successfully distinguished C. parapsilosis from C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. Previous studies in Iran had already described normal or high sensitivity of Iranian isolates of C. parapsilosis to FLC, ITC and AMB (10, 23–25).

Azole and polyen resistance were detected among all C. parapsilosis isolates. Three isolates were resistant to FLC (MIC ≥64 μg/ml), and three isolates were resistant to ITC (MIC ≥1 μg/ml). Only two C. parapsilosis were resistant to AMB. Monitoring of the susceptibility profiles of C. parapsilosis must highly advisable, although in this study FLU and ITR showed high sensitivity against C. parapsilosis. The combination of the ability to develop biofilms on catheters and other medical indwelling devices and decreased susceptibility to azole may become problematic (10).

Decreased susceptibilities to fluconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B were shown among C. parapsilosis isolates in all age groups in this present study. Continuing surveillance is critical to limit resistance among isolates (26). These findings confirm the worldwide reports of low levels of FLC resistance in C. parapsilosis isolated from blood cultures (20, 27, 28). In this study, the majority of isolates were fluconazole susceptible; Thus FLC is a reasonable drug for treatment of C. parapsilosis infections (4). However, other investigations indicated susceptible-dose dependent or resistance of C. parapsilosis isolates to FLC and AMB (10).

Pfaller et al. found no evidence of increasing azole resistance over time among C. parapsilosis isolates in their investigation in 124 medical centers worldwide (3). Another study revealed the susceptibility of C. parapsilosis isolates from fungemia in a Spanish hospital 100% for AMB, 95.6% for FLC, and 76.5% for ITC (29). Other investigations reported almost similar results (3, 4, 30).

Profiles in clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis may provide significant information for the control of antifungal resistance as well as distribution and susceptibility profiles in populations (8, 12). In addition, understanding of the drug susceptibility profiles particularly in azole and polyen resistances, help us to improve prophylactic and antifungal therapeutic strategies (7, 31).

Conclusion

This study presented antifungal susceptibility of clinical isolates of Candida parapsilosis in Iran. Decreased susceptibilities to fluconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B were shown in this present study. The majority of isolates were fluconazole susceptible. Thus, fluconazole is a practical drug for treatment of C. parapsilosis infections.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Mohammadi R, Mirhendi H, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, et al. ( 2013). Molecular identification and distribution profile of Candida species isolated from Iranian patients. Med Mycol, 51( 6): 657– 663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mirhendi H, Bruun B, Schønheyder HC, et al. ( 2010). Molecular screening for Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis among Danish Candida parapsilosis group blood culture isolates: proposal of a new RFLP profile for differentiation. J Med Microbiol, 59( 4): 414– 420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfaller M, Diekema D, Gibbs DL, et al. ( 2008). Geographic and temporal trends in isolation and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis: a global assessment from the ARTEMIS DISK Antifungal Surveillance Program, 2001 to 2005. J Clin Microbiol, 46( 3): 842– 849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Cuenca-Estrella M, et al. ( 2006). Epidemiology, risk factors, and prognosis of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections: case-control population-based surveillance study of patients in Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J Clin Microbiol, 44( 5): 1681– 1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Girmenia C, Martino P, Bernardis FDe, et al. ( 1996). Rising incidence of Candida parapsilosis fungemia in patients with hematologic malignancies: clinical aspects, predisposing factors, and differential pathogenicity of the causative strains. Clin Infect Dis, 23( 3): 506– 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuhn DM, Mukherjee PK, Clark TA, et al. ( 2004). Candida parapsilosis characterization in an outbreak setting. Emerg Infect Dis, 10( 6): 1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levin A, Costa S, Mussi NS, et al. ( 1998). Candida parapsilosis Fungemia Associated with Implantable and Semi-Implantable Central Venous Catheters and the Hands of Healthcare Workers. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 30( 4): 243– 249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Safdar A, Perlin DS, Armstrong D, et al. ( 2002). Hematogenous infections due to Candida parapsilosis, changing trends in fungemic patients at a comprehensive cancer center during the last four decades. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 44( 1): 11– 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weems JJ. ( 1992). Candida parapsilosis: epidemiology, pathogenicity, clinical manifestations, and antimicrobial susceptibility. Clin Infect Dis, 14( 3): 756– 766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silva AP, Miranda IM, Lisboa C, et al. ( 2009). Prevalence, distribution, and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Microbiol, 47( 8): 2392– 2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tavanti A, Davidson AD, Gow NAR, et al. ( 2005). Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis spp. nov. to replace Candida parapsilosis groups II and III. J Clin Microbiol, 43( 1): 284– 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alborzi A, Badiee P, Davarpanah MA, et al. ( 2010). Distributions and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species from mucosal sites in HIV positive patients. Arch Iran Med, 13( 4): 282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Fiori B, et al. ( 2005). Mechanisms of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 49( 2): 668– 679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davey KG, Holmes AD, Johnson EM, et al. ( 1998). Comparative evaluation of FUNGITEST and broth microdilution methods for antifungal drug susceptibility testing of Candida species and Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Microbiol, 36( 4): 926– 930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. ( 1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, 18: 315– 322. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mirhendi H, Makimura K, Khoramizadeh M, et al. ( 2006). A one-enzyme PCR-RFLP assay for identification of six medically important Candida species. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi, 47( 3): 225– 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. CLSI ( 2008). Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard—3rd ed. CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Park BJ, et al. ( 2005). Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in cases of Candida bloodstream infection: results from population-based surveillance, Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J Clin Microbiol, 43( 4): 1829– 1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pfaller M, Diekema D, Jones RN, et al. ( 2002). Trends in antifungal susceptibility of Candida spp. isolated from pediatric and adult patients with bloodstream infections: SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997 to 2000. J Clin Microbiol, 40( 3): 852– 856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez D, Almirante B, et al. ( 2005). In vitro susceptibilities of bloodstream isolates of Candida species to six antifungal agents: results from a population-based active surveillance programme, Barcelona, Spain, 2002–2003. J Antimicrob Chemother, 55( 2): 194– 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy I, L. G. Rubin LG, Vasishtha S, et al. ( 1998). Emergence of Candida parapsilosis as the predominant species causing candidemia in children. Clin Infect Dis, 26( 5): 1086– 1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abi-Said D, Anaissie E, Uzun O, et al. ( 1997). The epidemiology of hematogenous candidiasis caused by different Candida species. Clin Infect Dis, 24( 6): 1122– 1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shokohi T, Bandalizadeh Z, Hedayati MT, et al. ( 2011). In vitro antifungal susceptibility of Candida species isolated from oropharyngeal lesions of patients with cancer to some antifungal agents. Jundishapur J Microbiol, 4( 2): S19– S26. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Badiee P., Alborzi A. ( 2011). Susceptibility of clinical Candida species isolates to antifungal agents by E-test, Southern Iran: A five year study. Iran J Microbiol, 3( 4): 183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khosravi A, Shokri H, P Mansouri P, et al. ( 2008). Candida species isolated from nails and their in vitro susceptibility to antifungal drugs in the department of Dermatology (University of Tehran, Iran). Med Mycol, 18( 4): 210– 215. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfaller M, D. Diekema D, Jones RN, et al. ( 2001). International Surveillance of Bloodstream Infections Due to Candida Species: Frequency of Occurrence and In Vitro Susceptibilities to Fluconazole, Ravuconazole, and Voriconazole of Isolates Collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J Clin Microbiol, 39( 9): 3254– 3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pfaller M, Diekema D. ( 2002). Role of sentinel surveillance of candidemia: trends in species distribution and antifungal susceptibility. J Clin Microbiol, 40( 10): 3551– 3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pfaller M, Diekema D. ( 2004). Twelve years of fluconazole in clinical practice: global trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida. Clin Microbiol Infect, 10( s1): 11– 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martí-Carrizosa M, Sánchez-Reus F, March F, et al. ( 2014). Fungemia in a Spanish hospital: the role of Candida parapsilosis over a 15-year period. Scand J Infect Dis, 46( 6): 454– 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richter SS, Galask RP, Messer SA, et al. ( 2005). Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida species causing vulvovaginitis and epidemiology of recurrent cases. J Clin Microbiol, 43( 5): 2155– 2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trick WE, Fridkin SK, Edwards JR, et al. ( 2002). Secular trend of hospital-acquired candidemia among intensive care unit patients in the United States during 1989–1999. Clin Infect Dis, 35( 5): 627– 630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]