Abstract

Background

Enteral nutrition (EN) is recommended as the preferred route for early nutrition therapy in critically ill adults over parenteral nutrition (PN). A recent large randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed no outcome differences between the two routes. The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effect of the route of nutrition (EN versus PN) on clinical outcomes of critically ill patients.

Methods

An electronic search from 1980 to 2016 was performed identifying relevant RCTs. Individual trial data were abstracted and methodological quality of included trials scored independently by two reviewers. The primary outcome was overall mortality and secondary outcomes included infectious complications, length of stay (LOS) and mechanical ventilation. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the treatment effect by dissimilar caloric intakes, year of publication and trial methodology. We performed a test of asymmetry to assess for the presence of publication bias.

Results

A total of 18 RCTs studying 3347 patients met inclusion criteria. Median methodological score was 7 (range, 2–12). No effect on overall mortality was found (1.04, 95 % CI 0.82, 1.33, P = 0.75, heterogeneity I2 = 11 %). EN compared to PN was associated with a significant reduction in infectious complications (RR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.48, 0.87, P = 0.004, I2 = 47 %). This was more pronounced in the subgroup of RCTs where the PN group received significantly more calories (RR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.37, 0.82, P = 0.003, I2 = 0 %), while no effect was seen in trials where EN and PN groups had a similar caloric intake (RR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.80, 1.10, P = 0.44, I2 = 0 %; test for subgroup differences, P = 0.003). Year of publication and methodological quality did not influence these findings; however, a publication bias may be present as the test of asymmetry was significant (P = 0.003). EN was associated with significant reduction in ICU LOS (weighted mean difference [WMD] -0.80, 95 % CI −1.23, −0.37, P = 0.0003, I2 = 0 %) while no significant differences in hospital LOS and mechanical ventilation were observed.

Conclusions

In critically ill patients, the use of EN as compared to PN has no effect on overall mortality but decreases infectious complications and ICU LOS. This may be explained by the benefit of reduced macronutrient intake rather than the enteral route itself.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1298-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Nutrition therapy, Enteral nutrition, Parenteral nutrition, Critically ill, Intensive care unit, Infections, Randomized controlled trial

Background

Artificial nutrition support has evolved into a primary therapeutic intervention to prevent metabolic deterioration and loss of lean body mass with the aim to improve the outcome of critically ill patients. Apart from the timing of initiation and the targeted amount of macronutrients, the route of delivery is viewed as an important determinant of the effect of the nutritional intervention. Using the enteral route is considered to be more physiologic, providing nutritional and various non-nutritional benefits including maintenance of structural and functional gut integrity as well as preserving intestinal microbial diversity [1–3]. The disadvantage of enteral nutrition (EN) is related to a potential lower nutritional adequacy particularly in the acute disease phase and in the presence of gastrointestinal dysfunction [4, 5]. In contrast, parenteral nutrition (PN) may better secure the intended nutritional intake but is associated with more infectious complications, most likely due to hyperalimentation and hyperglycemia, as consistently shown in earlier meta-analyses [6–9]. These clinical data have translated into widespread consensus among current international guideline recommendations [10–13] and expert opinions [14, 15] that the enteral route is preferred in critically ill patients without a contraindication to EN.

Recently, Harvey and coworkers conducted the largest randomized controlled trial (RCT) to date with respect to the effect of the route of nutrition on the outcome of critically ill adult patients [16]. In this pragmatic RCT involving 2388 patients, neither a significant difference in mortality nor infectious complications was found between the patients receiving total PN or EN within 36 hours after admission and up to a maximum of 5 days. These results have challenged the paradigm that EN is superior to PN with regard to clinical outcomes in critical illness.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to perform an updated systematic literature review and meta-analysis of this topic to evaluate the overall effect of the route of nutrition (EN versus PN) on clinical outcomes in adult critically ill patients.

Methods

Search strategy and study identification

A literature review was conducted to identify all relevant RCTs published between 1980 and January 2016 in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The following keywords or medical subject headings were used: “randomized”, “clinical trial”, “nutrition support”, “artificial feeding”, “enteral nutrition”, “parenteral nutrition”, “intensive care”, “critical illness”, and “critically ill”. The literature search was not confined to articles written only in English. The authors’ personal files and reference lists of relevant review articles were also reviewed. Neither ethics board approval nor patient consent was required due to the nature of a systematic review.

Study eligibility criteria

Trials were included only if they met the following characteristics:

Type of study: RCT with a parallel group.

Population: critically ill adult patients (≥18 years of age), defined as patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). In the event that the information on the study population was unclear, we considered a mortality rate higher than 5 % in the control group to be consistent with critical illness. We excluded RCTs performed in elective surgery patients (such as cardiac surgery patients) even if patients were cared for in an ICU in the postoperative period.

Intervention: enteral versus parenteral nutrition

Trial outcomes: the trial reported clinically relevant outcomes. Overall mortality was the primary outcome for this meta-analysis. Where available, we extracted data regarding the primary mortality outcome reported as the principal outcome of the study, including ICU, hospital, 28-day mortality or other. Secondary outcomes were infections, ICU and hospital length of stay (LOS), and duration of mechanical ventilation with definitions of infections as defined in the original articles. As in previous meta-analyses conducted by our group, we excluded those trials that reported only nutritional, biochemical, metabolic, or immunologic outcomes.

Data abstraction

The methodological quality of the included trials was assessed in duplicate by two independent reviewers using a data abstraction form with a scoring system from 0 to 14 according to the following criteria as previously described [8, 17]:

(a) the extent to which randomization was concealed, (b) blinding, (c) analysis based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, (d) comparability of groups at baseline, (e) extent of follow-up, (f) description of treatment protocol, (g) co-interventions, (h) definition of clinical outcomes.

Disagreement concerning the individual score of each of the defined categories was resolved by consensus between the two reviewers. Moreover, attempts were made to contact the authors of the included trials in order to request further information not contained in the published article, if needed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane IMS, Oxford, UK) with a random effects model. All trial data were combined to estimate the pooled risk ratio (RR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for mortality and infections and overall weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95 % confidence intervals for LOS and mechanical ventilation data. We calculated pooled RRs using the Mantel-Haenszel estimator, and WMDs were estimated by the inverse variance approach. The random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird was applied to estimate variances for the Mantel-Haenszel and inverse variance estimators [18]. In case RRs were undefined they were excluded for studies with no event in either arm. Heterogeneity testing was performed using a weighted Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test and quantified by the heterogeneity I2 statistic as implemented in RevMan. Differences between subgroups were analyzed using the test of subgroup differences described by Deeks et al. [19], and the results expressed using the P values.

Generating funnel plots and testing asymmetry of outcomes using the method proposed by Rücker et al. [20] addressed possible publication bias. We considered P < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Subgroup analyses

A predefined subgroup analysis was performed to further explore whether the treatment effect of either route is associated with significant differences in the caloric intake across the study groups (EN compared to PN). A priori, we hypothesized that a possible negative treatment effect of PN on mortality, infectious complications and length of stay is related to a higher caloric intake. We used the reported significance level on caloric intake across groups from each study to determine the allocation to the subgroup. We also assessed the effect of trial publication date and trial quality on the outcome based on the hypothesis that older or methodologically weaker studies tended to yield a more negative treatment effect of PN. For this purpose, we designated trials with a publication date later than 1995 (median year 1994–1995) as newer and trials with a methodological score of more than 7 (median score) as methodologically stronger, respectively. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding two studies [21, 22] we were uncertain if the patients were truly critically ill [21] and about the trial results [22] and authors did not respond to attempts to obtain clarification.

Results

Study identification and selection

The literature search identified 83 potentially eligible randomized controlled trials, of which 65 were excluded for the following reasons (see Table A1 in Additional file 1): (a) patients not considered to be adult critically ill patients (N = 42), (b) no relevant clinical outcomes meeting inclusion criteria reported (N = 4), (c) being duplicate studies, reviews of published trials or subgroups of included studies (N = 11), (d) non-randomized or pseudo-randomized study design (N = 7), and/or (e) control group received a non-standard enteral formula (N = 1).

Thus, 18 RCTs with a total number of 3347 critically ill adult patients were finally included in the meta-analysis, whereof 1681 patients were treated with EN and 1666 patients with PN.

The median methodological score of the included 18 RCTs was 7 (range, 2–12) of which 10 RCTs were rated with a score ≤7 and 8 RCTs with a score >7. The median year of publication was 1994–1995 with 10 RCTs published before or in 1995 and 8 RCTs after 1995. All results were based on the individual trial data shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Included randomized controlled trials of enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients

| Author | Year | Population | Setting | Total patientsa | EN group | PN group | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapp et al. | 1983 | Head-injured patients | Single-center | 38 | 18 | 20 | [37] |

| Adams et al. | 1986 | Critically ill trauma | Single-center | 46 | 23 | 23 | [38] |

| Young et al. | 1987 | Brain-injured patients | Single-center | 51 | 28 | 23 | [39] |

| Peterson et al. | 1988 | Critically ill patients with abdominal trauma | Single-center | 59 | 29 | 30 | [40] |

| Cerra et al. | 1988 | Critically ill patients | Single-center | 70 | 33 | 37 | [41] |

| Moore et al. | 1989 | Abdominal trauma | Single-center | 75 | 39 | 36 | [42] |

| Kudsk et al. | 1992 | Abdominal trauma | Single-center | 98 | 52 | 46 | [43] |

| Dunham et al. | 1994 | Blunt trauma | Single-center | 28b | 12 | 16 | [44] |

| Borzotta et al. | 1994 | Closed head injury | Single-center | 59 | 36 | 23 | [45] |

| Hadfield et al. | 1995 | Mixed ICU medical-surgical | Single-center | 24 | 13 | 11 | [46] |

| Kalfarentzos et al. | 1997 | Severe acute pancreatitis | Single-center | 38 | 18 | 20 | [47] |

| Woodcock et al. | 2001 | ICU patients requiring nutrition support | Single-center | 38 | 17 | 21 | [27] |

| Casas et al. | 2007 | Severe acute pancreatitis | Single-center | 22 | 11 | 11 | [48] |

| Chen et al. | 2011 | Medical ICU | Single-center | 98b | 49 | 49 | [49] |

| Justo Meirelles et al. | 2011 | Traumatic brain injury | Single-center | 22 | 12 | 10 | [21] |

| Wang et al. | 2013 | Surgical ICU (severe acute pancreatitis) | Single-center | 121b | 61 | 60 | [22] |

| Sun et al. | 2013 | Surgical ICU (severe acute pancreatitis) | Single-center | 60 | 30 | 30 | [50] |

| Harvey et al. | 2014 | Mixed medical-surgical | Multi-center | 2400 | 1200 | 1200 | [16] |

EN enteral nutrition ICU intensive care unit PN parenteral nutrition

aTotal number includes number of ICU patients randomized in the trial, even if analysis was not according to intention-to-treat principle

bPatients randomized to a third intervention group (combined enteral and parenteral nutrition) of the concerned trial were excluded from this meta-analysis

Table 2.

Methodology and relevant outcome parameters of the included randomized clinical trials of enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients

| Study | Methods (score) | Mortality, N (%)a | Infections, N (%)b | LOS, days, mean ± SD (N) | Mechanical ventilation, days, mean ± SD (N) | Caloric intakec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN | PN | EN | PN | EN | PN | EN | PN | EN | PN | ||

| 1. Rapp et al. 1983 [37] | C.Random: not sure | 9/18 (50) | 3/20 (15) | NR | Hospital 49.4d | Hospital 52.6d | 10.3d | 10.4d | 685 P = 0.001 |

1750 | |

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (4) | |||||||||||

| 2. Adams et al. 1986 [38] | C.Random: not sure | 1/23 (4) | 3/23 (13) | 15/23 (65) | 17/23 (74) | ICU 13 ± 11 (19) | ICU 10 ± 10 (17) | 12 ± 11 (17) | 10 ± 10 (13) | 2088 NSf | 2572 |

| ITT: yes | Hospital 30 ± 21 (19) | Hospital 31 ± 29 (17) | |||||||||

| Blinding: no (8) | |||||||||||

| 3. Young et al. 1987 [39] | C.Random: not sure | 10/28 (36) | 10/23 (43) | 5/28 (18) | 4/23 (17) | NR | NR | 1671 P = 0.02 |

2299 | ||

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (6) | |||||||||||

| 4. Peterson et al. 1988 [40] | C.Random: not sure | NR | 2/21 (10) | 8/25 (32) | ICU 3.7 ± 0.8 (21) | ICU 4.6 ± 1.0 (25) | NR | Kcal on day 5 | |||

| 2204 P = 0.04 |

2548 | ||||||||||

| ITT: no | Hospital 13.2 ± 1.6 (21) | Hospital 14.6 ± 1.9 (24) | |||||||||

| Blinding: no (5) | |||||||||||

| 5. Cerra et al. 1988 [41] | C.Random: not sure | ICU 7/31 (22) | ICU 8/35 (23) | NR | NR | NR | Non-protein kcal | ||||

| 1684 NSf | 2000 | ||||||||||

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (2) | |||||||||||

| 6. Moore et al. 1989 [42] | C.Random: yes | NR | 5/29 (17) | 11/30 (37) | NR | NR | Non-protein kcal on day 5 | ||||

| ITT: no | 1847 P = 0.01 |

2261 | |||||||||

| Blinding: no (10) | |||||||||||

| 7. Kudsk et al. 1992 [43] | C.Random: not sure | ICU 1/51 (2) | ICU 1/45 (2) | 9/51 (16) | 18/45 (40) | Hospital 20.5 ± 19.9 (51) | Hospital 19.6 ± 18.8 (45) | 2.8 ± 4.9 (51) | 3.2 ± 6.7 (45) | Kcal/kg/d | |

| ITT: no | 15.7 P < 0.05 |

19.1 | |||||||||

| Blinding: single (10) | |||||||||||

| 8. Dunham et al. 1994 [44] | C.Random: not sure | 1/12 (7) | 1/15 (8) | NR | NR | NR | NSf | ||||

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (8) | |||||||||||

| 9. Borzotta et al. 1994 [45] | C.Random: not sure | 5/28 (18) | 1/21 (5) | 51/28 (28) | 39/21 (21) | Hospitale 39 ± 23.1 | Hospitale 36.9 ± 14 | NR | 2097 NSf | 1961 | |

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (6) | |||||||||||

| 10. Hadfield et al. 1995 [46] | C.Random: not sure | ICU 2/13 (15) | ICU 6/11 (55) | NR | NR | NR | NSf | ||||

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (7) | |||||||||||

| 11. Kalfarentzos et al. 1997 [47] | C.Random: not sure | ICU 1/18 (6) | ICU 2/20 (10) | 5/18 (28) | 0/20 (50) | ICU 11 (5–21)d | ICU 12 (5–24)d | 15 (6–16)d | 11 (7–31)d | Non-protein kcal/kg/d | |

| ITT: no | Hospital 40 (25–83)d | Hospital 39 (22–73)d | 24.1 NSf | 24.5 | |||||||

| Blinding: single (9) | |||||||||||

| 12. Woodcock et al. 2001 [27] | C.Random: yes | 9/17 (53) | 5/21 (24) | 6/16 (38) | 11/21 (52) | 33.2 ± 43 (16) | 27.3 ± 18.7 (18) | NR | % caloric target (30 kcal/kg/d) achieved | ||

| ITT: yes | 54.1 P < 0.001 |

96.7 | |||||||||

| Blinding: single (12) | |||||||||||

| 13. Casas et al. 2007 [48] | C.Random: no/unsure | Hospital 0/11 (0) | Hospital 2/11 (18) | 1/11 (9) | 3/11 (27) | Hospital 30.2 (average) | Hospital 30.7 (average) | NR | Kcal/kg/d | ||

| ITT: Yes | 20.1 NSf | 20.8 | |||||||||

| Blinding: no (8) | |||||||||||

| 14. Chen et al. 2011 [49] | C.Random: yes | 20-day 11/49 (22) | 20-day 10/49 (20) | 5/49 (10) | 18/49 (37) | ICU 9.09 ± 2.75 | ICU 9.60 ± 3.06 | 7.95 ± 2.11 | 8.23 ± 2.42 | NR | |

| ITT: yes | |||||||||||

| Blinding: no (7) | Hospital 23.32 ± 5.6 | Hospital 22.24 ± 3.27 | |||||||||

| 15. Justo Meirelles et al. 2011 [21] | C.Random: no | Not specified 1/12 (8.3) | Not specified 1/10 (10) | Total infectious complications 2/12 (16.7) | Total infectious complications 4/10 (40) | ICU 14 (5–26) | ICU 14 (6–24) | NR | Cumulative kcal over 5d | ||

| ITT: no | Pneumonia 2/12 (16.7) | Pneumonia 2/10 (20) | 5985 P = 0.34 |

6586 | |||||||

| Blinding: no (5) | Sepsis 0 | Sepsis 2/10 (20) | |||||||||

| 16. Wang et al. 2013 [22] | C.Random: no | Hospital 3/61 (5) | Hospital 7/60 (12) | Pancreatic sepsis 13/61 (21) | Pancreatic sepsis 24/60 (40) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| ITT: no | |||||||||||

| Blinding: double (7) | MODS 15/61 (24.6) | MODS 22/60 (36.7) | |||||||||

| 17. Sun et al. 2013 [50] | C.Random: no | Hospital 2/30 (7) | Hospital 1/30 (3) | Pancreatic 3/30 (10) | Pancreatic 10/30 (33) | ICU 9 (5–14) | ICU 12 (8–21) | NR | NR | ||

| ITT: no | MODS 5/30 (17) | MODS 13/30 (43) | |||||||||

| Blinding: no (6) | SIRS 12/30 (40) | SIRS 22/30 (73) | |||||||||

| 18. Harvey et al. 2014 [16] | C.Random: yes | ICU 352/1197 (29.4) | ICU 317/1190 (26.6) | Total infectious complications 194/1197 (16.2)g | Total infectious complications 194/1191 (16.3)g | ICU 11.3 ± 12.5 (1197) | ICU 12 ± 13.5 (1190) | 8.2 ± 9.3 (1197) | 8.7 ± 11.5 (1189) | Cumulative kcal/kg/d over 5d | |

| ITT: yes | Hospital 450/1186 (37.9) | Hospital 431/1185 (36.4) | Pneumonia 143/1197 (11.9) | Pneumonia 135/1191 (11.3) | Hospital 26.8 ± 33.2 (1186) | Hospital 27.5 ± 33.9 (1185) | 74 NSf | 89 | |||

| 30-day 409/1195 (34.2) | 30-day 393/1188 (33.1) | Bloodstream infections 21/1197 (1.8) | Bloodstream infections 27/1191 (2.9) | ||||||||

| Blinding: no (8) | 90-day 464/1188 (39.1) | 90-day 442/1184 (37.3) | Surgical infections 12/1197 (1.0) | Surgical infections 10/1191 (0.8) | |||||||

Data are presented as total number and percentage for mortality and infections. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation with total number of patients per group shown in brackets for LOS and mechanical ventilation

C.Random concealed randomization, d days, ITT intention to treat, kcal kilocalories, LOS length of stay, MODS multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, N number, NR not reported, NS not significant, SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome

aPresumed hospital mortality unless otherwise specified

bRefers to the number of patients with infections unless otherwise specified

cCaloric intake is presented as the mean daily kcal during the studies’ intervention period or as otherwise specified

dMedian/mean values, no standard deviation reported hence not included in meta-analysis

ePresumed hospital length of stay

fNo data on caloric intake or P value provided, respectively but caloric intake reported to be non-significantly different in the manuscript

gData on ICU patients obtained directly from authors

Effect of EN versus PN on mortality

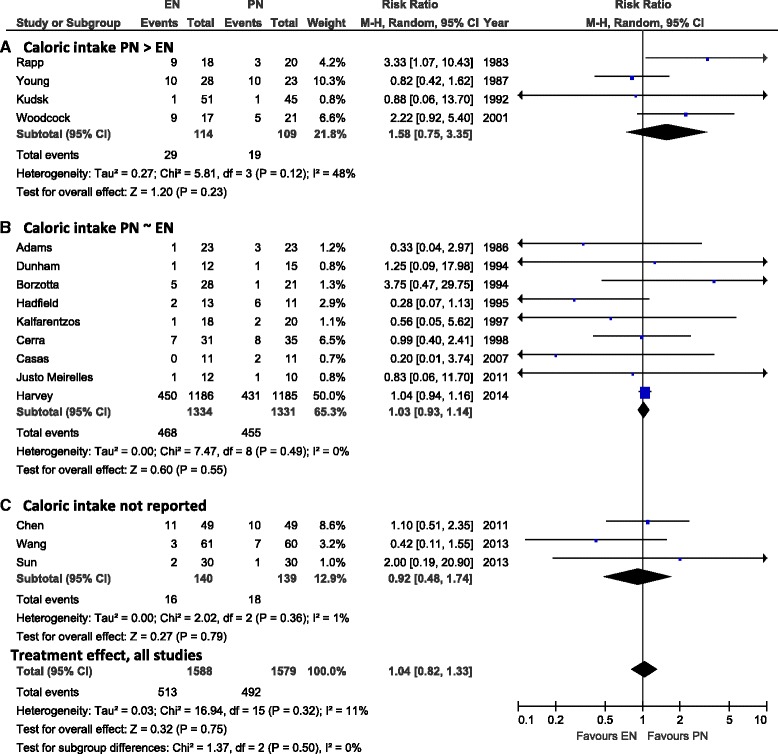

Aggregating data from all studies reporting on mortality (N = 16) there was no difference in overall mortality between the groups receiving EN or PN (RR 1.04, 95 % CI 0.82, 1.33, P = 0.75, heterogeneity I2 = 11 %) (Fig. 1). In the subgroup analysis where trials were aggregated according to the caloric intake across groups, no effect on mortality was seen in trials (N = 4) where the PN group received significantly more calories than the EN group (RR 1.58, 95 % CI 0.75, 3.35, P = 0.23, heterogeneity I2 = 48 %) or in the nine trials where the caloric intake was reported to be non-significantly different across groups (RR 1.03, 95 % CI 0.93, 1.14, P = 0.55, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.55) (Fig. 1, Panels a and b). Three RCTs did not report the caloric intake across study groups (Fig. 1, Panel c). In the sensitivity analysis excluding two studies [21, 22], there was still no difference in mortality between groups (RR 1.08, 95 % CI 0.83, 1.39, P = 0.57, heterogeneity I2 = 14 %).

Fig. 1.

Effects on overall mortality in studies comparing enteral versus parenteral nutrition (N = 16 studies). Panel a shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the caloric intake in the PN group was significantly higher than in the EN group, Panel b shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the PN and EN groups received similar caloric intake, and Panel c includes the trials where caloric intake was not reported. CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition

Effect of EN versus PN on infectious complications

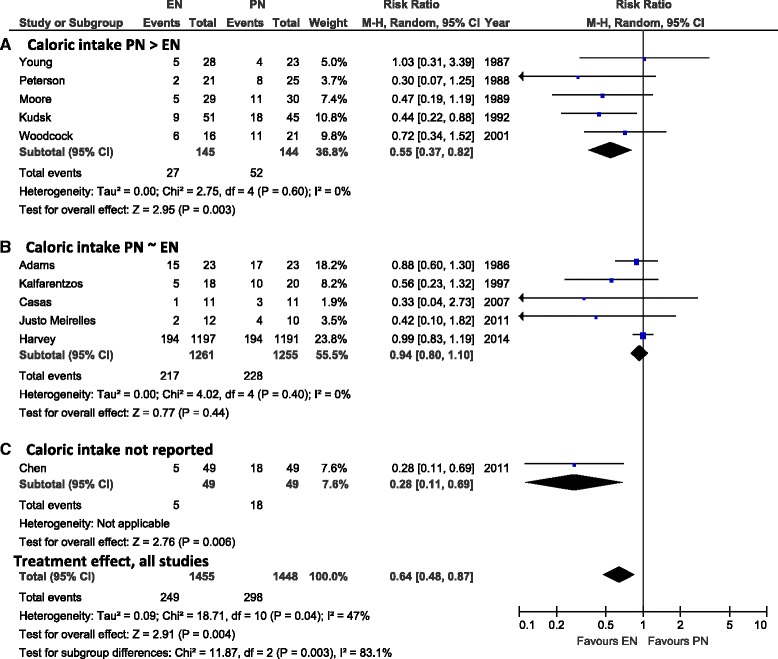

Eleven trials were aggregated which reported on infectious complications. EN compared to PN was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of infectious complications (RR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.48, 0.87, P = 0.004, heterogeneity I2 = 47 %; Fig. 2). The significant difference was also seen in the subgroup analysis of five aggregated trials in which the PN group had a significantly higher caloric intake than the EN group (RR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.37, 0.82, P = 0.003, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %) but not when the five trials were aggregated where caloric intake was similar between EN and PN groups (RR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.80, 1,10, P = 0.44, heterogeneity I2 = 0 % [test for subgroup differences: P = 0.003]) (Fig. 2, Panels a and b). One trial with data on infectious complications did not report the caloric intake across the EN and PN group (Fig. 2, Panel c). EN compared to PN was still associated with a significant reduction in infectious complications (RR 0.58, 95 % CI 0.41, 0.8, P = 0.001, heterogeneity I2 = 29 %) in the sensitivity analysis excluding the two studies with inconclusive status of critical illness [21, 22].

Fig. 2.

Effects on infectious complications in studies comparing enteral versus parenteral nutrition (N = 11 studies). Panel a shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the caloric intake in the PN group was significantly higher than in the EN group, Panel b shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the PN and EN groups received similar caloric intake, and Panel c includes one trial where caloric intake was not reported. CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition

Effect of EN versus PN on ICU and hospital length of stay

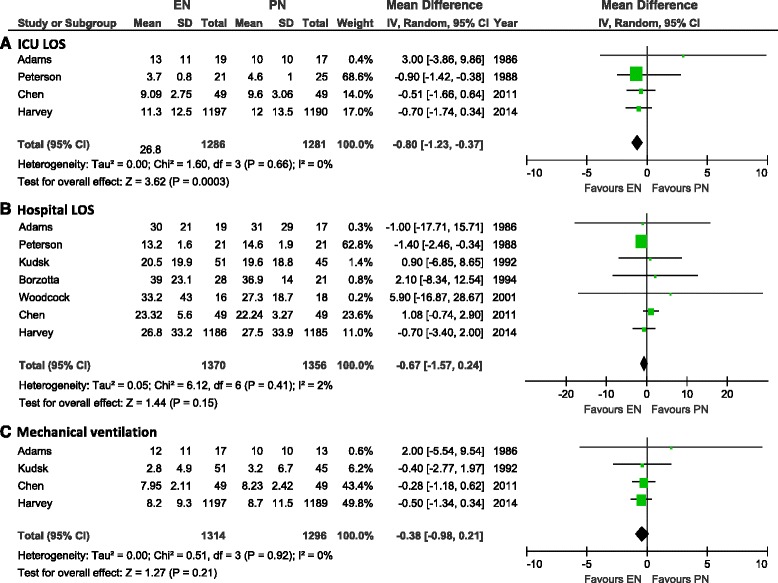

Only four studies reported on ICU LOS (in mean and standard deviation [SD]) and when the data were aggregated, the use of EN was associated with a significant reduction in ICU LOS (WMD −0.80, 95 % CI −1.23, −0.37, P = 0.0003, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %, Fig. 3, Panel a). In the subgroup analysis aggregating trials according to the caloric intake across groups, the significant difference was not observed in the two trials where caloric intake was similar between EN and PN groups (RR −0.47, 95 % CI −2.23, 1,29, P = 0.60, heterogeneity I2 = 8 %) (see Figure A1 in Additional file 2). A total of seven RCTs reported on hospital LOS (with mean and standard deviation) where no significant difference was found between EN and PN (WMD −0.67, 95 % CI −1.57, 0.24, P = 0.15, heterogeneity I2 = 2 %; Fig. 3, Panel b). The non-significant difference remained in the subgroup analysis where trials were aggregated according to the caloric intake across groups (RR −0.67, 95 % CI −1.57, 0.24, P = 0.15, heterogeneity I2 = 2 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.08) (see Figure A2 in Additional file 2).

Fig. 3.

Effects on length of stay and mechanical ventilation in studies comparing enteral versus parenteral nutrition. Panel a shows aggregated trials with information on ICU length of stay, Panel b shows aggregated trials with information on hospital length of stay. Panel c shows aggregated trials with information on length of mechanical ventilation (in mean and standard deviation). CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, ICU intensive care unit, IV inverse variance, LOS length of stay, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition, SD standard deviation

Effect of EN versus PN on mechanical ventilation

A total of four RCTs reported on length of mechanical ventilation (in mean and standard deviation) with no overall effect observed (WMD −0.38, 95 % CI −0.98, 0.21, P = 0.21, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %, Fig. 3, Panel c).

Effect of trial quality and publication date on outcomes and risk of publication bias

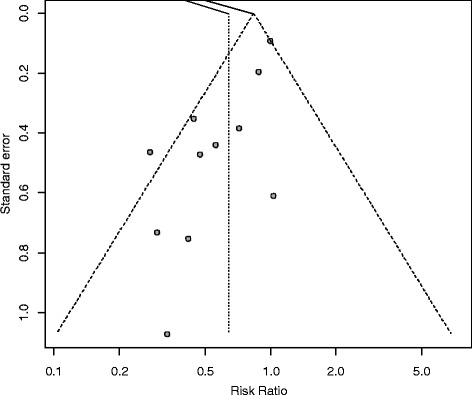

According to the subgroup analyses, there was no effect of either route of nutrition on overall mortality in high-quality trials (N = 7 RCTs; RR 1.05, 95 % CI 0.94, 1.16; P = 0.38, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %) compared to low-quality trials (N = 9 RCTs; RR 1.00, 95 % CI 0.62, 1.60; P = 1.00, heterogeneity I2 = 30 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.85). This also applied to the comparison of older (N = 8 RCTS ≤ 1995; RR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.56, 1.83; P = 0.98, heterogeneity I2 = 33 %) versus more recent publications (N = 8 RCTs > year 1995; RR 1.05; 95 % CI 0.94, 1.16; P = 0.38, heterogeneity I2 = 0 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.90). With respect to infectious complications, the positive treatment effect of EN remained significantly independent of methodological trial quality (N = 4 RCTs with score ≤ 7; RR 0.42; 95 % CI 0.23, 0.77; P = 0.005; heterogeneity I2 = 6 % and N = 7 RCTs with score > 7; RR 0.76; 95 % CI 0.58, 0.99; P = 0.04; heterogeneity I2 = 37 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.08) (see Figure A3 in Additional file 3) and independent of the trial publication date (N = 6 RCTs > 1995; RR 0.61; 95 % CI 0.37, 0.99; P = 0.05, heterogeneity I2 = 55 % and N = 5 RCTs ≤ 1995; RR 0.62; 95 % CI 0.39, 0.98; P = 0.04, heterogeneity I2 = 39 %; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.94) (see Figure A4 in Additional file 4). Results regarding the treatment effect of EN versus PN on ICU and hospital LOS in both subgroup analyses also remained concordant compared with the primary analyses. Funnel plots for all outcome measures were created to further test for potential publication bias. The test for asymmetry was found to be significant for the reported endpoint infectious complications (P = 0.003) (Fig. 4). No significant differences were found with respect to the remaining endpoints of overall mortality (P = 0.61), ICU LOS (P = 0.34), hospital LOS (P = 0.30) or mechanical ventilation (P = 0.65) (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot for 11 RCTs reporting the endpoint infectious complications. Test for asymmetry P = 0.003

Discussion

This updated meta-analysis on the effect of the route of nutrition (EN versus PN) on clinical outcomes included 18 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3347 randomized critically ill adult patients. Overall, there was no difference in mortality between the two routes of nutrition. EN as compared to PN led to a significant reduction in the number of infectious complications and ICU LOS while no significant effect was found with respect to hospital LOS and mechanical ventilation. However, the positive treatment effect of EN on infectious morbidity and ICU LOS may be attributed to differences in caloric intake between study groups. Furthermore, funnel plot analysis revealed evidence for significant publication bias for the trials reporting on infectious complications.

Comparison to other meta-analyses

Six previous meta-analyses comparing the effect of EN versus PN on clinical outcomes of critically ill adults reported no significant overall difference in mortality between the two routes of nutrition [6, 7, 9, 23–25]. The meta-analysis by Simpson and Doig [25] including 11 RCTs only showed a mortality benefit of PN in a predefined subgroup analysis where PN was compared to delayed EN (odds ratio [OR] 0.29, 95 % CI 0.12, 0.70, P = 0.006; heterogeneity I2 = 0 %, statistical heterogeneity P = 0.60). In the absence of an overall mortality effect, all of these meta-analyses showed significant reductions in the rate of infectious complications with the use of EN and one meta-analysis also showing a significant reduction of hospital LOS (WMD = 1.20 days; 95 % CI 0.38, 2.03; P = 0.004) [9].

In contrast to these previous meta-analyses, our updated results include the data of the recent multicenter RCT (“Calories trial”) by Harvey and coworkers [16]. In this pragmatic trial including 2400 critically ill patients, the use of total PN was compared with EN for a duration of 5 days after ICU admission. The calorie and protein intake was similar, albeit low with respect to the predefined nutrition target in both groups, while initiation of oral feeding was allowed if clinically indicated during the intervention period. Neither were there significant differences in the 90-day mortality primary endpoint nor in the rate of infectious complications or other secondary outcome measures including LOS variables and duration of mechanical ventilation. Why the increased infectious morbidity seen with PN in the former trials and meta-analyses was not observed in this latest largest RCT may have been related to the equally hypocaloric delivery of macronutrients via both routes.

Effect of dissimilar caloric intake

In contrast to the results of the Calories trial [16], the overall significant positive treatment effect of EN on infectious morbidity and ICU LOS remained in our updated meta-analysis. On the one hand, this overall treatment effect may reflect the positive non-nutritional effects of EN in terms of preservation of gut integrity and intestinal microbial diversity as well as promotion of gut-mediated immunity, all of which may support the systemic immune response [2, 26]. Presumably, the duration of the intervention (5 days) in the Calories trial [16] was likely too short or not intense enough in a population with a mortality rate of 34 % that the beneficial non-nutritional, trophic effects of EN became evident with respect to infectious morbidity and ICU LOS. On the other hand, our subgroup findings support the hypothesis that not the route per se but rather likely the dissimilar amount of calories delivered may have influenced the treatment effect on infectious complications. While there was a significant treatment effect difference in the subgroup of five RCTs where caloric intake was reported to be significantly higher in the PN group, no treatment effect on infectious complications was observed in the five trials with similar caloric intake across the study groups. This latter subgroup observation was largely driven by the Calories trial contributing 23.8 % of the overall estimate [16]. Furthermore, studies showing differences in infectious complications were associated with publication bias. Except for one RCT [27], the caloric intake in the PN group was gradually increased to target in all aggregated trials. Still, PN as compared to EN poses a higher risk of providing macronutrients in excess of the metabolic capacity, particularly in the early phase of illness and in the absence of appropriate metabolic control [28]. Caloric overfeeding per se is regarded to negatively influence outcomes with an increased risk of infectious complications while a restricted delivery of macronutrients or the avoidance of overfeeding may preserve autophagy and thus likely positively influence outcome [29, 30]. Unfortunately, owing to the limited number of trials in which the relation of nutritional intakes and predefined targets were reported, we were neither able to further explore the treatment effect of nutritional adequacy nor hyperglycemia on infectious complications in more detail. With respect to the effect of EN-specific complications such as vomiting, aspiration or diarrhea on clinical outcomes, we were unable to complete another subgroup analysis due to inconsistent reporting in the included RCTs. The Calories trial revealed that PN as compared to EN was associated with a lower rate of vomiting and diarrhea but a higher rate of constipation [16]. However, the impact of EN-specific complications remains inconclusive given the non-significant differences in major clinical outcomes in the Calories trial and two other large RCTs comparing the effect of different EN feeding strategies [31, 32].

Effect of trial quality and publication bias

Most of the RCTs that were aggregated in our meta-analysis were single-center trials reporting small total number of patients, and ten RCTs were published more than 20 years ago. Based on the hypothesis that older or methodologically weaker studies per se tended to yield the more negative treatment effect of PN, we performed additional subgroup analyses as well as funnel plots to assess risk of publication bias. In the early meta-analysis by Braunschweig et al., the positive treatment effect of EN compared to PN on infection rates was independent of the publication date and trial quality score [6]. While the positive treatment effect of EN on infectious morbidity accordingly appeared to be independent of the publication date and methodological trial quality in our meta-analysis, the funnel plot analysis revealed significant asymmetry with respect to infectious complication rates. This bias is apparently driven by the published smaller trials showing a larger treatment effect weakening the strength of the inference we can make about the overall effect of the route of nutrition on infectious complication rates.

Strength and limitations

The strengths of our meta-analysis are the comprehensive and most up-to-date search of the worldwide literature without restriction to only English-written articles, the inclusion of data from the largest and most recent RCT by Harvey and coworkers [16], the duplicate data abstraction and specific criteria for searching and analysis, and the analysis of trial quality, publication year, and publication bias. Limitations of our meta-analysis include the missing outcome data points in some of the included trials, and the small number of aggregated trials with data on the clinical endpoints ICU LOS and duration of mechanical ventilation. Further limitations are the variation in reporting the caloric intake, the time of nutrition intervention, and the definitions used for infections with or without adjudication across the trials included in the subgroup analysis. We were also unable to separate the effect of protein intake via both routes on the reported clinical endpoints among the included trials. Thus, there may be other covariates driving the observed findings that were not adjusted for in our meta-analysis. This may also pertain to possible treatment effect differences of EN versus PN among specific subpopulations of critically ill patients, such as those with a different nutritional risk upon ICU admission. The results of our meta-analysis may not be applicable to patients with a relative short-term or absolute contraindication for EN where the treatment effect of PN (as compared to standard care or no nutrition) on clinical outcomes may differ, as shown in two recent large RCTs [33, 34]. Moreover, the effect on long-term functional outcomes were not studied in the aggregated RCTs but are currently viewed as the more appropriate endpoints to be influenced by different nutritional interventions including the route and amount of nutrition [14, 35]. Lastly, we did not examine cost-effectiveness of the two strategies of nutrition due to the inconsistency of reported data in the trials. It is likely that EN will incur less cost as compared to PN as shown by a secondary analysis of the Calories trial [36].

Conclusions

In this comprehensive and most up-to-date systematic review we found that the route of nutrition (EN versus PN) does not impact mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill adult patients. Overall, the use of EN as compared to PN significantly reduced the rate of infectious complications and length of ICU stay. However, the different treatment effect concerning infectious morbidity favouring EN must be interpreted in light of the observed differences in caloric intake across study groups and publication bias of included trials. Although these observations reduce the strength of inference with respect to the negative effects of PN on infectious morbidity, the observed favourable effects of EN on ICU LOS, the ease of access, and lower costs in patients who tolerate EN should be considered. Therefore, in accordance with the most recent guideline recommendations [11, 12], we posit that EN still should be considered the first-line nutritional therapy in adult critically ill patients with a functioning gastrointestinal tract.

Key messages

This updated meta-analysis on effects of EN versus PN on clinical outcomes included 18 RCTs with 3347 randomized critically ill patients

There was no significant difference in mortality between patients fed via EN or PN

Compared to PN, the use of EN was associated with a significant reduction of infectious complications and ICU LOS

This positive treatment effect of EN compared to PN may be attributed to differences in caloric intake and significant publication bias among aggregated trials

EN still should be considered first-line nutritional therapy over PN in critically ill patients with a functioning gastrointestinal tract

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Canadian Critical Care Guidelines Committee members and the external reviewers for their work on the literature review.

Funding

There was no funding for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- C.Random

concealed randomization

- CI

confidence interval

- EN

enteral nutrition

- ICU

intensive care unit

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- IV

inverse variance

- kcal

kilocalories

- LOS

length of stay

- MODS

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- N

number

- NR

not reported

- NS

not significant

- OR

odds ratio

- PN

parenteral nutrition

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RR

relative risk

- SD

standard deviation

- SIRS

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- WMD

weighted mean difference

Additional files

Excluded studies of enteral versus parenteral nutrition. (PDF 109 kb)

Subgroup analysis comparing the effect of enteral versus parenteral nutrition according to the caloric intake on length of intensive care unit stay (N = 4 studies). Panel A shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the caloric intake in the PN group was significantly higher than in the EN group, Panel B shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the PN and EN groups received similar caloric intake and Panel C including one trial where caloric intake was not reported. CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition. Figure A2. Subgroup analysis comparing the effect of enteral versus parenteral nutrition on length of hospital stay according to the caloric intake (N = 7 studies). Panel A shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the caloric intake in the PN group was significantly higher than in the EN group, Panel B shows the subgroup of aggregated trials in which the PN and EN groups received similar caloric intake and Panel C including one trial where caloric intake was not reported. CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, IV inverse variance, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition. (PDF 148 kb)

Subgroup analysis comparing the effect of enteral versus parenteral nutrition on infectious complications in higher versus lower quality trials (with the median methodological score 7 as cutoff). CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition. (PDF 87 kb)

Subgroup analysis comparing the effect of enteral versus parenteral nutrition on infectious complications in newer versus older trials (with the publication date 1995 as cutoff). CI confidence interval, EN enteral nutrition, M-H Mantel-Haenszel test, PN parenteral nutrition. (PDF 88 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

GE received lecture fees and travel support from Fresenius Kabi, Abbott, and B. Braun Melsungen and was a member of the Reducing Deaths Due to Oxidative Stress post-trial advisory board meeting (Fresenius Kabi) and Gastro-Intestinal tolerance advisory board meeting (Nutricia). ARHvZ has received honoraria for advisory board meetings, lectures, and travel expenses from Abbott, Baxter, Danone, Fresenius Kabi, Nestle, Novartis, and Nutricia. DKH has received research grants and speaker honorarium from Fresenius Kabi, Baxter, and Biosyn. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GE contributed to the evaluation and interpretation of data and was the primary author and editor of the manuscript. ARHvZ, MK, KNJ, and MMcC contributed to the evaluation and interpretation of data as well as writing and editing of all drafts of the manuscript. DKH contributed to the development of the review concept, study grading, study selection and evaluation and interpretation of data, and also assisted in primary editing of all drafts of the manuscript. ML contributed to the development of the review concept, study grading, study selection and evaluation and interpretation of data; performed much of the primary statistical analysis and meta-analysis of data; and contributed significantly to the writing and editing of all drafts of the manuscript. XJ and AD contributed significantly to the statistical analysis of data and participated in the interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Barrett M, Demehri FR, Teitelbaum DH. Intestine, immunity, and parenteral nutrition in an era of preferred enteral feeding. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:496–500. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClave SA, Heyland DK. The physiologic response and associated clinical benefits from provision of early enteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009;24:305–15. doi: 10.1177/0884533609335176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClave SA, Martindale RG, Rice TW, Heyland DK. Feeding the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2600–10. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahill NE, Dhaliwal R, Day AG, Jiang X, Heyland DK. Nutrition therapy in the critical care setting: what is “best achievable” practice? An international multicenter observational study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:395–401. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c0263d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gungabissoon U, Hacquoil K, Bains C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, clinical consequences, and treatment of enteral feed intolerance during critical illness. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39:441–8. doi: 10.1177/0148607114526450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braunschweig CL, Levy P, Sheean PM, Wang X. Enteral compared with parenteral nutrition: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:534–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gramlich L, Kichian K, Pinilla J, Rodych NJ, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK. Does enteral nutrition compared to parenteral nutrition result in better outcomes in critically ill adult patients? A systematic review of the literature. Nutrition. 2004;20:843–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyland DK, MacDonald S, Keefe L, Drover JW. Total parenteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1998;280:2013–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peter JV, Moran JL, Phillips-Hughes J. A metaanalysis of treatment outcomes of early enteral versus early parenteral nutrition in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:213–20. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000150960.36228.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhaliwal R, Cahill N, Lemieux M, Heyland DK. The Canadian critical care nutrition guidelines in 2013: an update on current recommendations and implementation strategies. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:29–43. doi: 10.1177/0884533613510948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, Biolo G, Calder P, Forbes A, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on parenteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015;19:35. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0737-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer P, Hiesmayr M, Biolo G, Felbinger TW, Berger MM, Goeters C, et al. Pragmatic approach to nutrition in the ICU: expert opinion regarding which calorie protein target. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey SE, Parrott F, Harrison DA, Bear DE, Segaran E, Beale R, et al. Trial of the route of aarly nutritional support in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1673–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Zanten AR, Dhaliwal R, Garrel D, Heyland DK. Enteral glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:294. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeks J, Higgins PT. Statistical algorithms in Review Manager 5. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes. Stat Med. 2008;27:746–63. doi: 10.1002/sim.2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Justo Meirelles CM, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Enteral or parenteral nutrition in traumatic brain injury: a prospective randomised trial. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26:1120–4. doi: 10.1590/S0212-16112011000500030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G, Wen J, Xu L, Zhou S, Gong M, Wen P, et al. Effect of enteral nutrition and ecoimmunonutrition on bacterial translocation and cytokine production in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res. 2013;183:592–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P, Canadian CCCPGC Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:355–73. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027005355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore FA, Feliciano DV, Andrassy RJ, McArdle AH, Booth FV, Morgenstein-Wagner TB, et al. Early enteral feeding, compared with parenteral, reduces postoperative septic complications. The results of a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1992;216:172–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson F, Doig GS. Parenteral vs. enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a meta-analysis of trials using the intention to treat principle. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:12–23. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martindale RG, Warren M. Should enteral nutrition be started in the first week of critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:202–6. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodcock NP, Zeigler D, Palmer MD, Buckley P, Mitchell CJ, MacFie J. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition: a pragmatic study. Nutrition. 2001;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dissanaike S, Shelton M, Warner K, O’Keefe GE. The risk for bloodstream infections is associated with increased parenteral caloric intake in patients receiving parenteral nutrition. Crit Care. 2007;11:R114. doi: 10.1186/cc6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derde S, Vanhorebeek I, Güiza F, et al. Early parenteral nutrition evokes a phenotype of autophagy deficiency in liver and skeletal muscle of critically ill rabbits. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2267–76. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans G, Casaer MP, Clerckx B, et al. Effect of tolerating macronutrient deficit on the development of intensive-care unit acquired weakness: a subanalysis of the EPaNIC trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:621–9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Solaiman O. Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1175–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1509259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:795–803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:506–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doig GS, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, et al. Early parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients with short-term relative contraindications to early enteral nutrition: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2130–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casaer MP, Van den Berghe G. Nutrition in the acute phase of critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1227–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1304623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadique Z, Grieve R, Harrison D, Rowan K. Cost-effectiveness of early parenteral versus enteral nutrition in critically ill patients. Value Health. 2015;18:A532. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rapp RP, Young B, Twyman D, et al. The favorable effect of early parenteral feeding on survival in head-injured patients. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:906–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.6.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams S, Dellinger EP, Wertz MJ, Oreskovich MR, Simonowitz D, Johansen K. Enteral versus parenteral nutritional support following laparotomy for trauma: a randomized prospective trial. J Trauma. 1986;26:882–91. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young B, Ott L, Twyman D, Norton J, Rapp R, Tibbs P, et al. The effect of nutritional support on outcome from severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:668–76. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.5.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peterson VM, Moore EE, Jones TN, Rundus C, Emmett M, Moore FA, et al. Total enteral nutrition versus total parenteral nutrition after major torso injury: attenuation of hepatic protein reprioritization. Surgery. 1988;104:199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerra FB, McPherson JP, Konstantinides FN, Konstantinides NN, Teasley KM. Enteral nutrition does not prevent multiple organ failure syndrome (MOFS) after sepsis. Surgery. 1988;104:727–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore FA, Moore EE, Jones TN, McCroskey BL, Peterson VM. TEN versus TPN following major abdominal trauma--reduced septic morbidity. J Trauma. 1989;29:916–22. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Fabian TC, Minard G, Tolley EA, Poret HA, et al. Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:503–11. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199205000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunham CM, Frankenfield D, Belzberg H, Wiles C, Cushing B, Grant Z. Gut failure - predictor of or contributor to mortality in mechanically ventilated blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 1994;37:30–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borzotta AP, Pennings J, Papasadero B, Paxton J, Mardesic S, Borzotta R, et al. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition after severe closed head injury. J Trauma. 1994;37:459–68. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199409000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hadfield RJ, Sinclair DG, Houldsworth PE, Evans TW. Effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on gut mucosal permeability in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1545–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.5.7582291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalfarentzos F, Kehagias J, Mead N, Kokkinis K, Gogos CA. Enteral nutrition is superior to parenteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: results of a randomized prospective trial. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1665–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800841207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casas M, Mora J, Fort E, et al. Total enteral nutrition vs. total parenteral nutrition in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:264–9. doi: 10.4321/S1130-01082007000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen F, Wang J, Jiang Y. Influence of different routes of nutrition on the respiratory muscle strength and outcome of elderly patients in respiratory intensive care unit. Chin J Clin Nutr. 2011;1:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun JK, Mu XW, Li WQ, Tong ZH, Li J, Zheng SY. Effects of early enteral nutrition on immune function of severe acute pancreatitis patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:917–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]