Abstract

Background

Skeletal muscle activation has been implicated as the source of pain associated with ICD shocks. We hypothesized that the skeletal muscle response to defibrillatory shocks could be attenuated with a tetanizing pre-pulse immediately prior to biphasic shock delivery.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to test the ability of tetanizing pre-pulses to reduce the skeletal muscle activation associated with defibrillation.

Methods

Seven adult pigs were studied. A left ventricular coil and subcutaneous dummy can in the right thorax were used to deliver either pure biphasic waveforms or test waveforms consisting of a tetanizing pulse of high-frequency alternating current (HFAC) ramped to an amplitude of 5–100 V over 0.25 to 1 s, immediately followed by a biphasic shock of approximately 9 J (ramped HFAC and biphasic, or rHFAC+B). We used limb acceleration and rate of force development (RoFD) as surrogate measures of pain. Test and control waveforms were delivered in sinus rhythm and induced VF to test defibrillation efficacy.

Results

Defibrillation threshold energy was indistinguishable between rHFAC+B and pure biphasic shocks. Peak acceleration and RoFD were reduced by 72%±7% and 71%±22%, respectively with a 25 V 1 s rHFAC+B waveform compared with pure biphasic shocks. Notably, rHFAC+B with a 9 J biphasic shock produced significantly less skeletal muscle activation than a 0.1J pure biphasic shock.

Conclusion

A putative source of ICD shock-related pain can be mitigated using a tetanizing pre-pulse followed by biphasic shock. Human studies will be required to assess true pain reduction with this approach.

Keywords: Defibrillation, Pain, Skeletal Muscle, ICD

Introduction

With the advent of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) 30 years ago sudden cardiac death was rendered treatable. However, since patients are often fully conscious, the experience of ICD shocks has been linked to many psychological side effects, including anxiety and depression.1,2 In fact, the severity of anxiety associated with ICD shocks is similar to that of patients with panic disorder3 and some patients eventually develop panic disorder when more shocks are applied.4

The physiology that underlies shock-induced pain is not well understood. Direct nerve stimulation and secondary nociception via skeletal muscle activation have both been suggested as possible pathways,5 and patients occasionally report lingering muscle soreness in the days after a shock. Notably, the “pulling/tearing sensation” of muscle pain caused by electrically stimulated maximal contraction is not attenuated with sensory transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, suggesting that pain is mediated by the contraction itself.6 Previous studies have considered skeletal muscle as a target for reducing shock-induced pain, but these approaches required an invasive procedure to confine the defibrillation electric field to the myocardium.7,8 We hypothesized that the non-physiological, nearly instantaneous contraction associated with a standard biphasic shock is the source of pain during defibrillation. The purpose of this study was to develop a novel waveform to pre-stimulate skeletal muscle gradually to a fully contracted state before delivery of a biphasic shock. In this way the fast contraction, the putative source of pain, would be reduced using the same electrodes as with a standard ICD. We tested this hypothesis and provide validation for our novel method for pain measurement on the basis of patient descriptions of shock sensation.

Methods

Pig Model and Pain Measurement

All animal studies were performed under a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. Seven adult pigs (40–80 lbs.) were anesthetized with thiamylal, intubated, and then maintained on a ventilator using gaseous isoflurane (~0.8%–1.5%) and oxygen. In early tests on large animals with the coil in the right ventricle (not shown) we found that defibrillation was unsuccessful with a 480 V pulse, the maximum output of our custom-built arbitrary waveform defibrillator system. To achieve a lower defibrillation threshold, a standard ICD shock coil (Riata, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) was placed in the left ventricular apex via carotid arterial access under fluoroscopic guidance. A dummy can was placed subcutaneously in the right thorax and served as the return electrode. Using a custom waveform generator connected to the implanted coil and can, we delivered either ramped high-frequency alternating current followed by biphasic shock (rHFAC+B, see below) or biphasic shocks alone as controls. Test and control waveforms were delivered in sinus rhythm, and during induced VF to test defibrillation efficacy. A catheter was placed in the right ventricle to record a bipolar ventricular electrogram free of stimulation artifacts.

An accelerometer (Analog devices ADXL377) was attached to the right forelimb, and a force transducer (SM-50, Interface Mfg., Scottsdale, AZ, USA) to the left, to provide limb acceleration and rate of force development (RoFD) as surrogate measures of pain. Waveforms were generated with custom written MATLAB software and output with a digital-to-analog converter (National Instruments USB-6216 BNC, also used for data collection). RoFD was calculated from low pass filtered force traces using the differentiation algorithm developed by Chartrand et al.9 (See supplemental Fig. 2 for additional information.) The magnitude of the three dimensional acceleration was calculated and the peak values of acceleration and RoFD were measured from each shock application. A schematic of the experimental preparation is shown in Figure 1 with representative acceleration and RoFD results from a pure biphasic shock.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup: Waveforms (A) are applied to the animal (B) through a custom-built amplifier. A force transducer and accelerometer yield measurements (C) of acceleration (top) and RoFD (bottom). Asterisks indicate peak values for RoFD and acceleration. (A) and (C) illustrate application and measurement of a pure biphasic waveform.

Waveforms

A standard biphasic truncated exponential waveform (Figure 2A) was used as a control in all experiments (4 ms per phase with 4 ms time constant for ~66 % tilt). The test waveform consists of a tetanizing pulse of ramped high-frequency (1 kHz) alternating current (rHFAC) that grows linearly from 0 V to an amplitude of 5–100 V over 0.25, 0.5 or 1 s duration immediately followed by a ~480V (~9 J) biphasic shock (rHFAC+B, Figure 2B). The impedance varied between 40–60 Ω, so all energy estimates are based on a 50 Ω impedance.

Figure 2.

Waveforms: Standard biphasic waveform (A) with 4 ms per phase and 66 % tilt and rHFAC+B (B) shown with 250 ms duration and 25 V amplitude ramp. Biphasic waveforms are identical in A and B (amplitude= 480 V).

Defibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation episodes were induced using a 1–2 s 50 Hz 2–3 V AC waveform applied between the intracardiac shock coil and dummy can. Each defibrillation attempt was performed approximately 8 seconds after induction, and failed shocks were followed by a rescue shock from the internal electrodes (either rHFAC+B or Biphasic alone with shock amplitude of 480V). If the internal rescue shock failed, a subsequent external shock (Medtronic Physio-Control LIFEPACK 12) was applied. Rescue shocks were not included in calculations of defibrillation success. For each animal the biphasic amplitude was decreased until a shock failed to defibrillate and then multiple defibrillation attempts were made at that amplitude. The first failure amplitude varied between animals, so the relative success rate of defibrillation for biphasic and rHFAC+B was compared within animals.

Data and Statistical Analysis

For each animal RoFD and acceleration in response to rHFAC+B was normalized relative to the average values seen in these parameters in response to maximum strength pure biphasic shocks. This was required since smaller animals generated significantly less force than larger animals. Results are reported as mean ± S.D. Statistical significance was calculated with an unpaired Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The ability of rHFAC to suppress the skeletal muscle response to biphasic shock is demonstrated in Figure 3. The left panels show the waveform (Fig. 3A), acceleration (Fig. 3B), and RoFD (Fig. 3C) using a 450 V biphasic shock alone. The right panels show the corresponding waveform (Fig. 3D), acceleration (Fig. 3E), and RoFD (Fig. 3F) with rHFAC+B (25 V ramp, 1 s ramp duration and the same 450 V biphasic shock amplitude as in the left panels). We found a substantial reduction in peak acceleration and RoFD when using rHFAC+B compared with the biphasic shock alone. The skeletal muscle stimulation that is elicited by rHFAC+B is mostly confined to a brief period of acceleration during the first part of the rHFAC component, with little further activation caused by the biphasic shock component.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Biphasic (A) and rHFAC+B (D). Both Acceleration (B,E) and RoFD (C,F) decreased by about a factor of four when using rHFAC+B (peak values indicated with asterisks) compared with biphasic alone.

We tested a range of values for the waveform parameters shown in Figure 2B. The rHFAC frequency was fixed at 1 kHz, the ramp duration was set to 0.25 s, 0.5 s, or 1 s, and final ramp amplitude was set to 0 (pure biphasic), 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100 V. Biphasic shock amplitude was held constant in each experiment and was always >400 V. The results are shown in Figure 4 and are reported as the relative peak acceleration or RoFD normalized to that seen with pure biphasic shocks. As the duration is increased the relative peak values of acceleration and RoFD decrease for all ramp amplitudes above 10 V. For a given ramp duration, the peak values of RoFD and acceleration have a U-shaped dependence on ramp amplitude. At low ramp amplitudes the response is indistinguishable from a pure biphasic shock, and with ramp amplitudes up to 25 V, the peak RoFD decreases monotonically. At high ramp amplitudes, peak RoFD and acceleration increase because of greater skeletal muscle stimulation from the high frequency current itself (see supplemental Fig. 1). A 25 V amplitude, 1 s duration ramp was best able to suppress both RoFD (by 71%±22%) and acceleration (by 72%±7%) compared with the response to pure biphasic shocks.

Figure 4.

Summary Relationships: Peak acceleration (A) and RoFD (B) versus ramp amplitude for ramp durations of 0.25 s (red, dotted), 0.5 s (green, dashed), and 1 s (blue, solid). (n=6) For each duration, as ramp amplitude increases the peak values of RoFD and acceleration decrease to a minimum at a ramp amplitude of about 25 V and then increase or remain unchanged afterwards.

Next, in two pigs, we validated peak RoFD and peak acceleration against published results of pain thresholds in humans. Figure 5 shows acceleration (Fig. 5A) and RoFD (Fig. 5B) versus energy for standard biphasic waveforms (red dots and blue Xs, representing the two animals). Also shown in each panel is the response to an rHFAC+B waveform composed of a full 9 J biphasic shock preceded by a 25 V, 1 s duration HFAC ramp (black open squares). For standard biphasic shocks, RoFD and acceleration fall off below 0.1–1 J and remain relatively constant above this threshold. But, when pre-stimulated with rHFAC, peak acceleration and RoFD of a full strength (9 J) biphasic waveform are reduced to levels observed for 0.01–0.1 J pure biphasic waveforms, far below reported pain thresholds10–13 (vertical dashed line shown at 0.1 J). The complete range of biphasic energies was tested in only these two animals, but low energy shocks (<0.1 J) were tested in several others with similar results.

Figure 5.

Pain threshold comparison: Peak acceleration (A) and RoFD (B) for standard biphasic waveforms (red dots and blue Xs) versus estimated waveform energy. All values were normalized to the maximum (9 J) shock. Red dots and blue Xs are from two different animals. The black open squares are responses from six animals to rHFAC+B with a 25 V amplitude, 1 s duration ramp followed by the maximum 9 J biphasic shock. Dashed line at 0.1 J represents reported pain threshold for defibrillation. Acceleration and RoFD fall off below 0.1–1 J and remain relatively constant above this threshold.

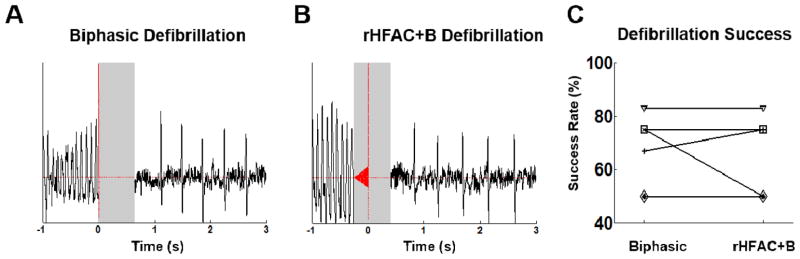

In a final set of experiments, VF was induced, and we compared biphasic and rHFAC+B shock success. Figure 6 shows representative defibrillation successes for pure biphasic (Fig. 6A) and rHFAC+B shocks (Fig. 6B). Defibrillation was achieved in 7 animals, and the success rate for both pure biphasic and rHFAC+B waveforms is given for each animal in Figure 6C. There was no significant difference in defibrillation success between rHFAC+B and pure biphasic shocks, suggesting they are equally effective.

Figure 6.

Defibrillation: Biphasic (A) and rHFAC+B (B) waveforms were both able to defibrillate in n=6 animals. The success rate was the same for both waveforms in four animals (C) and did not change significantly (p=0.978) over all six. ECG traces are blanked in grey boxes due to electrical artifacts from the applied fields. Note that there are two animals that remained at 50%.

Discussion

Main Findings

We found that pre-tetanizing stimulation of the chest with rHFAC significantly reduced the dynamics of skeletal muscle activation, with a 25 V, 1 s ramp reducing both acceleration and RoFD in forelimbs by more than 70 % (Figure 4). This reduction was observed even for rHFAC durations as low as 0.25 s. Reduction of RoFD and acceleration had a U-shaped dependence on ramp amplitude, reflecting a tradeoff between the ramp’s ability to blunt the biphasic response and its ability to directly stimulate the muscle. Lastly, the rHFAC pre-pulse does not appear to alter defibrillation efficacy.

Pain sensation and assessment, and prior work on ICD shock related pain

Pain induced by therapeutic shocks is an important limitation of ICDs. Patients report pain and lingering discomfort in skeletal muscle groups that contract with shocks. Anxiety, anger, depression, and stress levels were higher not only in the patients, but also in their families.14 Although defibrillation is the only effective option for treating an otherwise fatal arrhythmia, in a study of 119 patients with ICDs, 23% reported “dreading” the shock, while a surprising 5% preferred facing the risk of death over the pain of another shock.15 Pain is typically assessed in the patient with rating scales or observations of reactions to stimuli, but in the anesthetized animal these are inadequate. The utility of our surrogate metrics of pain derives from (1) the fact that they are objective measures, and (2) the observation that they have similar value for all shock energy levels known to be painful, and fall in observed value at shock levels below the typically reported threshold of pain. Biphasic shocks have been shown to be uncomfortable at around 0.1 J, and shocks at various energy levels above this threshold were indistinguishable by the patient.10 Moreover, all patients in that study requested sedation for shocks greater than 1 J. Other studies report similar results in the 0.4–1 J range.11–13 The defibrillation threshold for biphasic shocks in clinical trials16,17 is typically on the order of 8–10 J, with many patients requiring over 20 J, well above the pain threshold. In our study, the peak acceleration and RoFD response to pure biphasic shocks decreased only when shock energy was below 0.1–1 J, and were essentially constant above that threshold (Figure 5).

Prior attempts to reduce the pain of defibrillation by modifying standard biphasic waveforms have yielded only marginal benefits at best, and many studies report that simple changes in waveform shape and amplitude do not alter patient perception of shocks.11,13,18–21 Shock warning systems were developed in conjunction with biphasic shocks because uncertainty of when a shock would occur was a common stressor,22 but the psychological effect of expectation has been shown to worsen the perception of shocks.23,24 Further, additional shocks given within minutes tend to hurt more than initial shocks.11,12 Another pain reduction attempt used pre-pulses that were shown to reduce the pain perception associated with defibrillation-like shocks due to the suppression of activity within a ‘startle’ neural circuit,25,26 but proof of clinical efficacy has not been shown. Further, the shocks in these studies were delivered cutaneously, which is difficult to correlate with stimulation via implanted ICD electrodes due to the high impedance and concentration of nerves at the skin. Using pre-pulses in this way to disrupt the startle neural circuit is a mechanism distinct from the skeletal muscle suppression we are reporting. However, the efficacy of pain suppression from our approach depends on pain being mediated by adverse skeletal muscle activation. In related work in our laboratory, skeletal muscle activation was shown to be substantially attenuated by surrounding the heart in a conductive mesh to confine the defibrillation electric field to the myocardium,7,8 but this strategy would substantially increase the complexity of device implantation.

We have previously investigated alternating current as an alternative waveform to defibrillate,27,28 but skeletal muscle activation was increased. We noted, however, that the longer duration of AC would allow skeletal muscle to be gradually tetanized before a standard biphasic shock. Tetany has been used for many years as part of functional electrical stimulation (FES) therapy for various spinal cord injuries.29 FES uses tetanic contractions to retrain certain motor tasks,29–31 and while occasional discomfort is noted, it is not painful. We therefore stimulated tetanic contraction in the present study by delivering rHFAC through the same ICD electrodes used for defibrillation. Strikingly, rHFAC+B at ~9 J produced about the same peak RoFD as a 0.01 J biphasic shock, one tenth the pain threshold (see Figure 5). Thus, not only did rHFAC+B with a 400–480 V (~9 J) biphasic component produce significantly less skeletal muscle stimulation than a pure biphasic shock of the same energy, it elicited less muscle activation than even a small sub-defibrillatory biphasic shock having an amplitude well below the accepted threshold of pain.

Key Parameters of rHFAC+B Defibrillation

For both acceleration and RoFD the longest duration waveforms tested (1 s) were the best at mitigating the subsequent biphasic shock response. Longer duration waveforms have a lower rate of amplitude increase, and, since the amount of motor unit recruitment is proportional to the amplitude of an applied stimulus,32 fewer muscle fibers are stimulated per unit time. This is likely the cause of the lower acceleration and RoFD, though further experiments are required for verification.

Our data show that reduction of RoFD and acceleration were achieved in pigs within a narrow range of amplitudes around 25 V, so if a similar phenomenon holds for humans, it may be possible to identify an optimal amplitude that is effective for different patients. Further, 1 s waveforms were only marginally better at suppressing the biphasic response than 0.25 s waveforms (see Figure 4), and shorter duration ramps may be preferable to minimize energy requirements and duration of discomfort.

The results we have described should be consistent with any shock lead configuration, including the totally subcutaneous ICD. This eliminates the need for new electrode development and surgical techniques, making our method applicable for patients who already have an ICD since only the pulse generator would need to be replaced. Also, the additional energy required to produce the brief low-amplitude rHFAC component is only roughly 0.5 J for a 0.25 s, 25 V ramp. The energy can be decreased even further by decreasing the duty cycle of the ramp, although the efficacy of such a modified waveform needs to be tested. Thus, it is feasible to achieve nearly painless defibrillation with less than 5% additional energy cost over standard defibrillation, an important consideration in a battery-powered implanted device. It should be noted that we tested rHFAC+B with ramps of both square wave and sinusoidal waveforms, and the results were identical. Thus circuitry to produce either type of rHFAC+B waveform could be developed in a modified ICD.

Limitations

RoFD and acceleration are only surrogate measures of pain. While these metrics are similar to those used in prior work,7,8 they are not established predictors of pain. Only studies in human patients will allow us to test the pain of these waveforms directly and validate the use of RoFD and acceleration as pain surrogates. All contraction measurements were performed on forelimbs and not directly on thoracic muscles, which are likely subjected to higher field strengths during defibrillation, and are located where patients generally feel pain. It is likely that the muscle response is similar in intercostal and diaphragmatic muscles, but this should be verified in the future. Further, our tests were performed on anesthetized pigs which may alter contraction kinetics and strength.

The shock coil could not be placed in the standard location (right ventricle) and achieve consistent defibrillation because of the output limitations of our amplifier, but we believe this has little effect in determining the relative efficacy of the rHFAC+B waveform since pure biphasic waveforms were delivered as controls. Nonetheless, the standard lead configuration remains to be tested with our second generation device having higher output capabilities. The output limitations of the waveform amplifier also limited the defibrillation testing protocol. In the larger animals the success rate at the maximum possible shock strength was often below 70%. In the future a more systematic study to evaluate defibrillation efficacy and proarrhythmic potential should be performed.

Conclusions

Pre-tetanizing skeletal muscle before delivery of a standard biphasic shock substantially mitigates peak RoFD and peak acceleration of induced skeletal muscle activation, while defibrillation efficacy is preserved with the composite waveform. Human testing will be required to validate these findings, but our results represent a proof of concept for a novel strategy to realize more tolerable defibrillation.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

ICD shocks are painful and a source of great morbidity associated with this life-saving therapy. Previous strategies to mitigate this problem have failed. Since the pain is thought to be derived from skeletal muscle activation by the high-voltage shock, we developed and tested in an animal model a novel strategy in which a brief high-frequency electrical pulse is delivered to the ICD shock electrodes to tetanize skeletal muscle immediately before delivery of a standard biphasic defibrillatory shock. We found that with appropriate characteristics of the tetanizing pre-pulse, we could attenuate the subsequent response of skeletal muscle to the biphasic shock down to a level below that seen with 0.1J standard shocks. These findings offer proof of principle that mitigation of ICD shock-related pain is feasible, although human testing is essential to establish the true effect of this strategy on pain reduction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, the Abell Foundation, and a Mid-Atlantic American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship (D.H.). This work was partially supported by SBIR grant R44 HL127771-01 from the NIH.

Abbreviations

- HFAC

High Frequency Alternating Current

- rHFAC

ramped HFAC

- rHFAC+B

Combination rHFAC and B waveform

- RoFD

Rate of Force Development

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Berger, Tung, Tandri, Halperin, and Mr. Hunter hold a patent on the technology described in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- 1.Kamphuis HCM, de Leeuw JRJ, Derksen R, Hauer RNW, Winnubst JAM. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients: quality of life in recipients with and without ICD shock delivery: a prospective study. Europace [Internet] 2003;5:381–389. doi: 10.1016/s1099-5129(03)00078-3. cited 2014 Jun 11. Available from: http://europace.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1016/S1099-5129(03)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilge AK, Ozben B, Demircan S, Cinar M, Yilmaz E, Adalet K. Depression and anxiety status of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator and precipitating factors. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol [Internet] 2006;29:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00409.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16784428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauli P, Wiedemann G, Dengler W, Blaumann-Benninghoff G, Kühlkamp V. Anxiety in patients with an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator: what differentiates them from panic patients? Psychosom Med [Internet] 1999;61:69–76. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199901000-00012. cited 2014 Jun 11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10024069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godemann F, Ahrens B, Behrens S, Berthold R, Gandor C, Lampe F, Linden M. Classic conditioning and dysfunctional cognitions in patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia treated with an implantable cardioverter/defibrillator. Psychosom Med [Internet] 2001;63:231–238. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00006. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11292270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murgatroyd FD, Slade AKB, Sopher SM, Rowland E, Ward DE, Camm aJ. Efficacy and tolerability of transvenous low energy cardioversion of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laufer Y, Tausher H, Esh R, Ward AR. Sensory transcutaneous electrical stimulation fails to decrease discomfort associated with neuromuscular electrical stimulation in healthy individuals. Am J Phys Med Rehabil [Internet] 2011;90:399–406. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318214f64a. cited 2014 Jun 9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21765256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayanti V, Zviman MM, Nazarian S, Halperin HR, Berger RD. Novel electrode design for potentially painless internal defibrillation also allows for successful external defibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol [Internet] 2007;18:1095–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00936.x. cited 2014 Jan 2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17711432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayam V, Zviman M, Jayanti V, Roguin A, Halperin H, Berger RD. Internal defibrillation with minimal skeletal muscle activation: a new paradigm toward painless defibrillation. Heart Rhythm [Internet] 2005;2:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.06.030. cited 2014 Jan 2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16188591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chartrand R. Numerical Differentiation of Noisy, Nonsmooth Data. ISRN Appl Math. 2011;2011:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell aRJ, Spurrell PaR, Boodhoo LE, Sulke N. Long-term care of the patient with the atrial defibrillator. Am Heart J. 2004;147:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung J, Hahn SJ, Heisel A, Buob A, Schubert BD, Siaplaouras S. Defibrillation efficacy and pain perception of two biphasic waveforms for internal cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol [Internet] 2003;14:837–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02557.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12890046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhaus DM, Cardinal DS, Mongeon L, Musley SK, Foley L, Corrigan S. Internal defibrillation: pain perception of low energy shocks. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1090–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomassoni G, Newby KH, Kearney MM, Brandon MJ, Barold H, Natale A. Testing different biphasic waveforms and capacitances: effect on atrial defibrillation threshold and pain perception. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet] 1996;28:695–699. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00220-3. cited 2014 Apr 14. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0735109796002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougherty CM. Psychological reactions and family adjustment in shock versus no shock groups after implantation of internal cardioverter defibrillator. Heart Lung. 24:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad M, Bloomstein L, Roelke M, Bernstein aD, Parsonnet V. Patients’ attitudes toward implanted defibrillator shocks. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol [Internet] 2000;23:934–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb00877.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10879375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsovsky MR, Shorofsky SR, Gold MR. Effect of shock polarity on biphasic defibrillation thresholds using an active pectoral lead system. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:350–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold MR, Olsovsky MR, DeGroot PJ, Cuello C, Shorofsky SR. Optimization of transvenous coil position for active can defibrillation thresholds. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boriani G, Edvardsson N, Biffi M, Silvestri P, Martignani C, Valzania C, Diemberger I, Moulder JC, Mouchawar G, Poci D, Branzi A, Kroll MW. Plateau waveform shape allows a much higher patient shock energy tolerance in AF patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol [Internet] 2007;18:728–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00846.x. cited 2014 Jan 2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17504256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boriani G, Biffi M, Silvestri P, Martignani C, Valzania C, Diemberger I, Moulder C, Mouchawar G, Kroll M, Branzi A. Mechanisms of pain associated with internal defibrillation shocks: results of a randomized study of shock waveform. Heart Rhythm [Internet] 2005;2:708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.03.024. cited 2014 Apr 14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15992726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boriani G, Biffi M, Zannoli R, Branzi A, Magnani B. Transvenous internal cardioversion for atrial fibrillation: A randomized study on defibrillation threshold and tolerability of asymmetrical compared with symmetrical shocks. Int J Cardiol. 1999;71:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ammer R, Alt E, Ayers G, Lehmann G, Schmitt C, Pasquantonio J, Pütter K, Schmidt M, Schömig a. Pain threshold for low energy intracardiac cardioversion of atrial fibrillation with low or no sedation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol [Internet] 1997;20:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb04849.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9121996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuiper R, Nyamathi AM. Stressors and coping strategies of patients with automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1991;5:65–76. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumert J, Schmitt C, Ladwig K-H. Psychophysiologic and affective parameters associated with pain intensity of cardiac cardioverter defibrillator shock discharges. Psychosom Med [Internet] 68:591–597. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221379.17371.47. cited 2014 Apr 14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16868269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlaeyen JWS, Timmermans C, Rodriguez L-M, Crombez G, van Horne W, Ayers GM, Albert A, Wellens HJJ. Catastrophic thinking about pain increases discomfort during internal atrial cardioversion. J Psychosom Res [Internet] 2004;56:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00081-3. cited 2014 Apr 1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14987976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumenthal TD, Swerdlow CD. Electrical shocks to the arm elicit and inhibit startle eyeblinks. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:218–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal TD, Burnett TT, Swerdlow CD. Prepulses reduce the pain of cutaneous electrical shocks. Psychosom Med [Internet] 2001;63:275–281. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00012. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11292276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tandri H, Weinberg SH, Chang KC, Zhu R, Trayanova Na, Tung L, Berger RD. Reversible cardiac conduction block and defibrillation with high-frequency electric field. Sci Transl Med [Internet] 2011;3:102ra96. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002445. cited 2011 Oct 1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21957174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg SH, Chang KC, Zhu R, Tandri H, Berger RD, Trayanova Na, Tung L. Heart Rhythm [Internet] Vol. 10. Elsevier; 2013. Defibrillation success with high frequency electric fields is related to degree and location of conduction block; pp. 740–748. cited 2014 May 29. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23354078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch CL, Popovic MR, Rushton D. Functional Electrical Stimulation. IEEE Control Syst Mag [Internet] 2008;28:40–50. Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=4472378\nhttp://iopscience.iop.org/0967-3334/18/4/001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popovic MB, Popovic DB, Sinkjær T, Stefanovic A, Schwirtlich L. Restitution of reaching and grasping promoted by functional electrical therapy. Artif Organs. 2002;26:271–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern H, Boncompagni S, Rossini K, Mayr W, Fanò G, Zanin ME, Podhorska-Okolow M, Protasi F, Carraro U. Long-term denervation in humans causes degeneration of both contractile and excitation-contraction coupling apparatus, which is reversible by functional electrical stimulation (FES): a role for myofiber regeneration? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:919–931. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bickel CS, Gregory CM, Dean JC. Motor unit recruitment during neuromuscular electrical stimulation: a critical appraisal. Eur J Appl Physiol [Internet] 2011;111:2399–2407. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2128-4. cited 2013 Dec 14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21870119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.