Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by demyelination and progressive neurological disability. Previous studies have reported defects to mitochondria in MS including decreased expression of nuclear encoded electron transport chain subunit genes and inhibition of respiratory complexes. We previously reported increased levels of the hemoglobin β subunit (Hbb) in mitochondrial fractions isolated from postmortem MS cortex compared to controls. In the present study, we performed immunohistochemistry to determine the distribution of Hbb in postmortem MS cortex and identified proteins which interact with Hbb by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). We found that Hbb was enriched in pyramidal neurons in internal layers of the cortex and interacts with subunits of ATP synthase, histones, and a histone lysine demethylase. We also found that Hbb is present in the nucleus and that expression of Hbb in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells increased trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 4 (H3K4me3), a histone mark that regulates cellular metabolism. These data suggest that Hbb may be a part of a mechanism linking neuronal energetics with epigenetic changes to histones in the nucleus and may provide neuroprotection in MS by supporting neuronal metabolism.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Hemoglobin expression, Pyramidal neurons, Mass spectrometry, Mitochondrial genes, Histone methylation

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the demyelination and deterioration of neurons within the central nervous system (CNS) (Noseworthy et al. 2000). In MS, axonal and neuronal degeneration and inflammatory demyelination accumulate over time, resulting in progressive neurological disability (Bjartmar et al. 2000; De Stefano et al. 2001). Historically, MS was considered a white matter disease and the majority of research concerning MS was focused on understanding autoimmune demyelination. However, it has been established that cortical pathology, including extensive gray matter lesions and cortical atrophy, contribute to the progression of MS (Bo et al. 2006; Inglese et al. 2004; Fisher et al. 2008). The mechanisms involved in cortical pathology are not clear, but current hypotheses describe dysfunction of the mitochondria in the cortex in MS. In studies analyzing postmortem brain tissue, the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial respiration has been found to be altered in normal appearing gray matter (NAGM) in MS brains compared to NAGM in non-diseased brains (Dutta et al. 2006; Pandit et al. 2009; Witte et al. 2013). In a subsequent proteomic analysis of mitochondria in MS and control cortical tissue, hemoglobin β (Hbb) was found to be expressed in neurons and was more abundant in MS postmortem cortex compared to non-diseased cortex (Broadwater et al. 2011).

Until recently, erythrocytes were believed to be the only cell type to contain hemoglobin. The function of hemoglobin in red blood cells is to transport and exchange oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) in tissues. In red blood cells, hemoglobin exists as a heterotetramer of two hemoglobin α (Hba) and two hemoglobin β (Hbb) subunits. However, studies have now shown that various cell types other than erythrocytes, such as macrophages, epithelial cells, and neurons, also contain hemoglobin (Rahaman and Straub 2013). The discovery of Hba and/or Hbb expression in diverse cell types suggests that they have other roles in addition to their role in O2 and CO2 transport. Hemoglobins contain a heme-prosthetic group (Fe-protoporphyrin IX) which binds not only O2 and CO2 but also nitric oxide (NO), allowing them to also participate in redox and dioxygenase reactions (Reeder et al. 2010). In mesangial cells of the kidney, hemoglobin has been shown to act as an anti-oxidant (Nishi et al. 2008). Separate functions have also been described for the α and β subunits in some cell types. In macrophages, the hemoglobin β minor subunit is expressed without the α subunit and acts to scavenge NO (Liu et al. 1999). In vascular endothelial cells, Hba is expressed and has been shown to regulate NO release necessary for vasodilation when O2 concentrations are low (Straub et al. 2012). It is clear that hemoglobin has evolved to carry out diverse physiological functions in many different cell types. The role of hemoglobin in neurons in the CNS is still not clear. In order to better understand the function of Hbb and its potential role in providing neuroprotection in MS, we have analyzed the cortical distribution of Hbb by immunohistochemistry. We have also performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments with an Hbb antibody followed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify proteins interacting with Hbb in the MS cortex and in cultured primary neurons.

Methods

Immunofluorescent Staining

Postmortem MS and control cortical brain tissue was obtained under IRB protocol from the Rocky Mountain MS Center and the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center at UCLA. For immunofluorescent staining, frozen tissue blocks were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 24 h and cut 30 μm thick using a vibratome. Cortical tissue from five MS and four control brains was analyzed. Donor and tissue characteristics including age, sex, postmortem interval (PMI), and brain region are shown in Table 1. Blocking buffer was prepared as 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5 % Triton X-100 and 3 % normal donkey serum. Samples were blocked in blocking buffer for 1 h and then primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and applied to samples overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were applied in the following concentrations: Hbb (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA) 1:250, neurofilament (SMI32) (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA) 1:500, and tyrosine hydroxylase (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX) 1:250. Secondary antibodies were also applied in blocking buffer at 4 °C for 2 h. All secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and were applied at a concentration of 1:500. Secondary antibodies used are as follows: donkey anti-rabbit Alexafluor 488, donkey anti-goat Alexafluor 488, donkey anti-mouse Alexafluor 555, and donkey anti-goat Alexafluor 555. After incubation of secondary antibodies, samples were soaked in 10 mM cupric sulfate, 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer for 90 min to quench autofluorescence. Samples were mounted on microscope slides using Vectashield mounting medium for fluorescence with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Mounted samples were viewed with a Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope and imaged using the bundled software.

Table 1.

Donor and tissue characteristics

| Sample | Age (years) | Sex | PMI (h) | Region of cortex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS 1 | 79 | F | 7.0 | Parietal |

| MS 2 | 69 | M | 12.0 | Motor |

| *MS 3 | 63 | F | 23.0 | Frontal |

| *MS 4 | 78 | F | 7.8 | Parietal |

| *MS 5 | 79 | F | 7.4 | Parietal |

| *MS 6 | 53 | F | 3.0 | Parietal |

| *MS 7 | 61 | F | 6.0 | Parietal |

| *MS 8 | 36 | F | 3.0 | Parietal |

| C1 | 83 | F | 17.6 | Motor |

| C2 | 74 | M | 13.4 | Frontal |

| *C3 | 74 | F | 18.0 | Frontal |

| *C4 | 67 | M | 22.0 | Motor |

| *C5 | 74 | F | 4.5 | Frontal |

| *C6 | 80 | M | 9.5 | Parietal |

| *C7 | 59 | F | 19.5 | Frontal |

| *C8 | 35 | F | 9.3 | Parietal |

Immunostaining with neurofilament (SMI32) allowed the visualization of the cortical layers in each tissue block analyzed. Only sections containing all layers of the cortex with neural projections streaming perpendicular to the pial surface were included. With SMI32 as a guide to ensure that all layers of the cortical section were analyzed, contiguous ×20 objective fields were imaged from the outer edge of the cortex to the white matter. Image stacks spanning the depth of the tissue sections were acquired and the fields were stitched together with Fluoview software to create a map of the cortex spanning from the pial surface to cortical layer VI. SMI32 and Hbb immunoreactive neurons were counted in the external and internal cortical layers for sections from five MS and four control brains with Image J (Rasband 1997).

Primary Neuronal Cultures

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Kent State University. Primary neuronal cultures were isolated from E17 Sprague Dawley rat brains. Briefly, cerebral cortices were dissected from the whole fetal rat brain and meninges carefully removed. The rat cerebral cortex was mechanically dissociated in EMEM containing 10 % FBS using fire polished Pasteur pipettes and then passed through 70 μm pore-sized mesh. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation of 100×g for 10 min at 4 °C and resuspended with neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and N2. Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated tissue culture dishes and maintained at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 in a humidified incubator. Primary neurons were cultured for 10 days before protein isolation. Media was changed after 3 days to eliminate any hemoglobin from blood contamination. Total protein was isolated for identification of hemoglobin interacting proteins by co-IP followed by LC-MS/MS. To confirm the presence of hemoglobin in our cultures, some cells were incubated on coverslips and immunostained with antibodies to hemoglobin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and neurofilament (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) followed by the appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies Alexafluor 488 or Alexafluor 555 (both from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Western blotting of protein isolated from our cultured rat primary neurons also confirmed the presence of a hemoglobin 16-kDa band (not shown). Immunostained cells were imaged with a Fluoroview 1000 confocal microscope.

Protein Extraction and Co-IP for Mass Spectrometry

For co-IP experiments, total protein was isolated from cortical gray matter tissue from an MS brain and from rat primary neuronal cultures. Tissue or cells were homogenized with a mini-homogenizer for 60 s in five volumes of extraction buffer. Extraction buffer consisted of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05 % Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, and 2 μg/mL pepstatin. The samples were then spun at 12,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was taken and spun again at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was kept as the protein sample. Co-IP was performed with the protein isolated using the Pierce™ Classic Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). In order to form the Hbb and antibody immune complex, 1.0 mg of protein extract was incubated with 10 μg of an Hbb antibody (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA). Protein isolated from rat primary neurons was incubated with 10 μg of a hemoglobin antibody (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Protein was also immunoprecipitated with non-specific IgG as a control. The protein and antibodies were incubated for 2 h at room temperature, with the total reaction diluted to 500 μL in IP Lysis/Wash Buffer. IP Lysis/Wash Buffer consisted of 0.025 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.001 M EDTA, 1 % NP40, and 5 % glycerol at pH 7.4. After complex formation, 25 μL of washed magnetic beads were added to the complex solution and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The beads were washed with 500 μL IP Lysis/Wash Buffer and then with 500 μL of ultrapure water. The sample was eluted with 100 μL of low-pH elution buffer for 10 min at room temperature and then neutralized.

Eluted proteins from the Co-IP were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 5 min. The sample was run on a NuPAGE 4-12 % Bis Tris Gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Coomassie stained to visualize protein bands. The gel was washed and destained in distilled water. The protein lane was cut out of the gel and destained with 500 μL of 1:1 ACN (acetonitrile) and 100 mM ABC (ammonium bicarbonate) solution for 2–6 h. Next, the gel piece was dehydrated and hydrated with 200 μL 100 % ACN and 200 μL 100 mM ABC, respectively. Disulfide bonds were then reduced with 10 mM DTT at 56 °C for 45 min, and free cysteines were alkylated with 55 mM IAA (iodoacetamide) in the dark at RT for 45 min. The gel piece was then swelled in 50 mM ABC containing freshly prepared 10 ng/μL trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, sequencing-grade) and digested overnight at 37 °C. Subsequently, peptides were extracted 50 % ACN/25 mM ABC/5 % FA (formic acid) and dried in SpeedVac.

Reverse Phase LC-MS/MS Analysis and Protein Identification

For gel-based tandem mass spectrometry analysis, digested peptides were reconstituted with 0.1 % formic acid and analyzed by LC-MS/MS using an LTQ-Orbitrap Elites mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with a nanoAcquity™ Ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography system (Waters). The mobile phases included aqueous phase A (0.1 % FA in water) and organic phase B (0.1 % FA in 85 % ACN). Tryptic peptides were loaded onto a nanoACQUITY UPLC desalting trap column (180 μm × 20 mm nano column, 5 μm, 100 A°, Waters). Subsequently, peptides were resolved in a nanoACQUITY UPLC reversed phase column (75 μm × 250 mm nano column, 1.7 μm, 100 A°; Waters). Liquid chromatography was carried out using a gradient elution of 1–90 % of organic phase over 90 min at ambient temperature. Peptides were then introduced into the mass spectrometer via a nano-electrospray ion source at a flow rate of 0.3 μL/min. Full scan MS spectra were acquired at a resolution of 60,000 followed by 20 collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentations in a data-dependent manner. The dynamic exclusion list was confined to a maximum of 500 entries, with exclusion duration of 45 s and mass accuracy of 10 ppm for the precursor monoisotopic mass.

For protein identification, the LC-MS/MS raw files were acquired using the Thermo X-calibur software (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and searched by Mascot (version 2.3.01, Matrix Science) against the human Uniprot (71,434 sequences) database. Search settings were as follows: trypsin enzyme specificity; mass accuracy window for precursor ion, 10 ppm; mass accuracy window for fragment ions, 0.8 Da; variable modifications including carbamidomethylation of cysteines, one missed cleavage, and oxidation of methionine. The search results were then filtered using the cutoff criteria of p value ≤0.05.

Hbb Expression Construct and Transfections

Total RNA were extracted from approximately 50 mg human brain tissue using a SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of RNA were checked with a ND1000 Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Reverse transcription to produce cDNA was performed with a Brilliant III ultrafast SYBR Green QRT-PCR kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Full-length human Hbb cDNA was amplified by PCR from human brain cDNA using the following primer pairs: Hbb F 5′ATCCTCGAGTGCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACT 3′ and Hbb R 5′ ATCCCGGGTGGACAGCAAGAAAGCGAGCTT 3′. The resulting PCR product was cloned into pEGFP (Clontech Laboratories) and then subcloned into the XhoI and NheI sites of the pVitro2 mammalian expression vector (Invivogen, San Diego, CA). The constructed plasmid was confirmed by sequencing and the insert showed 100 % sequence similarity with the Hbb sequence from NCBI [hemoglobin β (NM_000518.4)].

Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were cultured in 1:1 mixture of EMEM and F-12 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 10 % FBS (MidSci, St. Louis, MO) in a 37 °C incubator with 5 % CO2. pVitro2 and pVitro2-Hbb constructs were purified and transfected into SH-SY5Y cells with TransIt Express transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. The pVitro2 and pVitro2-Hbb plasmids were incubated with the TransIt transfection reagent for 30 min to allow DNA complexes to form. The complexes were then added to SH-SY5Y cells already seeded on 100 mm culture plates to 80 % confluency and incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, protein was isolated and Western blotting was performed to measure levels of Hbb expression and histone methylation.

Western Blotting

Proteins were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on NuPage 4–12 % Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were then incubated in primary antibody overnight and then in the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h and immunoreactivity was detected with Luminol (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX). For quantitation of nuclear and mitochondrial Hbb protein levels in MS and control postmortem tissue, protein was isolated and fractionated according to the method of Pallotti and Lenaz (2007). Six MS and six control cortical gray matter tissue samples were analyzed (Table 1). The purity of fractions was determined by Western blotting with antibodies to the mitochondrial membrane protein aralar (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and the neuronal nuclear marker NeuN (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Western blots were also performed with an antibody to the astrocyte marker GFAP (not shown). Any samples exhibiting increased GFAP indicative of astrogliosis or a change in cellularity indicated by decreased NeuN were eliminated. Western blotting was performed with an antibody to Hbb (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA) and relative Hbb levels were determined after normalization to either NeuN for nuclear fractions or aralar for mitochondrial fractions. To confirm identification of Hbb interacting proteins, Western blots were performed with protein immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Hbb or non-specific IgG. Blots were incubated with antibodies to Hbb (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), ATP5A1 (Novex Life Technologies, Waltham, MA), and histone H3 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). To measure Hbb and H3K4me3 levels in transfected SH-SY5Y cells, blots were incubated with antibodies to either Hbb (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA) or histone H3 trimethylated on lysine 4 (H3K4me3) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Hbb levels were normalized to GAPDH (Millipore, Temecula, CA) and H3K4me3 was normalized to histone H3. Protein levels were determined by densitometry with Image J from at least two independent experiments. Statistical significance of changes in protein levels was determined with a Student's t test with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

Results

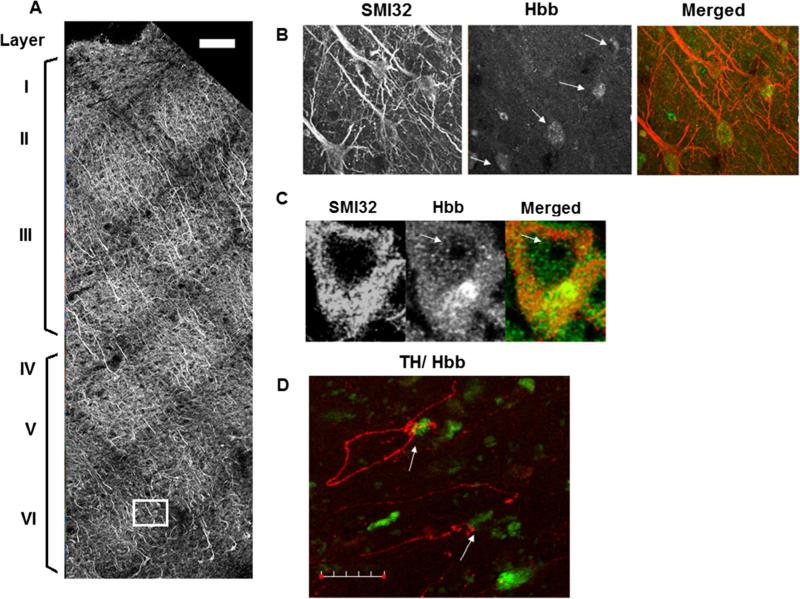

To understand the distribution of hemoglobin in the cortex and to determine whether this distribution is altered in MS, we performed immunofluorescent staining with antibodies to hemoglobin and the neuronal marker neurofilament (SMI32) in cortical sections obtained from five MS and four control brains (Table 1). A representative confocal image showing the subdivisions of the cortex ascertained by SMI32 immunostaining in motor cortex from an MS sample is shown in Fig. 1a. Representative confocal images showing colocalization of Hbb and SMI32 in neurons in MS cortical sections are shown in Fig. 1b. We did not find any statistically significant difference between MS and control brains in the overall percentage of Hbb + cells or in the cortical distribution of Hbb. We identified a total of 703 SMI32+ neurons from immunostained sections from the motor and parietal cortex across five MS brains and found that 33 % were also immunoreactive for Hbb. For control brains, 534 SMI32 positive neurons were identified across four brains and 172 also expressed Hbb (32 %). In addition, we found that Hbb expression was enriched in the internal layers of the cortex (layers IV–VI) compared to external layers (layers I–III) in both MS and control brains. For MS brains, 300 SMI32 positive neurons were identified in the external layers of the cortex, and 67 were also immunoreactive for Hbb (22 %). In the internal layers, 403 SMI32 positive neurons were identified and 167 expressed Hbb (42 %). For controls, in external layers, 49 of 197 SMI32 positive neurons expressed Hbb (25 %). In the internal layers, 337 SMI32 positive neurons were counted and 123 also expressed Hbb (36 %). Most Hbb containing neurons exhibited pyramidal cell morphology. Hbb expression was found to be localized predominantly in the cytoplasm of these cells, but nuclear staining was also detected as shown in Fig. 1c. Weak staining for Hbb was observed in the nucleus, but not in the nucleolus in pyramidal neurons in both MS and control cortical tissue. It has been reported that SMI32, which stains non-phosphorylated neurofilament-H, is a marker of dystrophic neurons and axons, and is indicative of axonal damage. In our hands we did not observe a difference in neurofilament staining with SMI32 or with the SMI31 antibody which stains phosphorylated neurofilament in postmortem tissue. We also stained tissue blocks with SMI31 and Hbb and obtained similar results (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Cortical distribution of Hbb expressing pyramidal neurons in MS cortex. a Representative confocal image from MS motor cortex immunostained with antibodies to neurofilament (SMI32) and Hbb. Sequential ×20 confocal images were acquired from the pial surface extending through cortical layer VI and stitched into a single image. Cortical layers were visualized by SMI32 staining shown in grayscale. Scale bar represents 100 μm. b Panel shows the boxed region in A at higher magnification. SMI32 and Hbb immunoreactivity can be seen in pyramidal neurons denoted by arrows. SMI32 and Hbb channels are shown in grayscale and the merged image on the right shows colocalization of SMI32 (red fluorescence) and Hbb (green fluorescence). SMI32 and Hbb positive cells were counted in cortical tissue sections from five MS brains. We found that on average 33 % of SMI32+ cells were also immunoreactive for Hbb. In external layers of the cortex (layers I–III), 22 % of SMI32+ neurons were Hbb+. In cortical layers IV–VI, the internal cortical layers, 42 % of SMI32 neurons also expressed Hbb. c Hbb expression is observed in the nucleus but not in the nucleolus (denoted by arrows) in pyramidal cells. d Representative confocal image showing an MS cortical section immunostained with antibodies to TH (red fluorescence) and Hbb (green fluorescence). Arrows denote TH positive axons appearing to contact cell bodies of Hbb positive cells. Scale bar represents 30 μm

In addition to SMI32 and Hbb labeling, sections of MS and control brains were stained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and Hbb (Fig. 1d). TH catalyzes the rate limiting step of the formation of catecholamines, which include the neurotransmitters dopamine, adrenaline, and noradrenaline. TH has also been localized within interneurons, and thus can be used as a histochemical marker for interneurons (Benavides-Piccione and DeFelipe 2007). These TH positive interneurons do not synthesize catecholamines, but appear to be GABAergic. An abundance of TH labeled neurons was found in the MS samples, each with morphologies consistent with interneurons. TH labeled neurons did not appear to contain Hbb; however, some TH labeled neurons were observed to form what appeared to be synapses to cells which did contain Hbb (Fig. 1d). TH labeled neurons appeared to contact the cell bodies of Hbb expressing neurons as opposed to dendrites, suggesting these TH expressing neurons are GABAergic inhibitory interneurons, as inhibitory synapses often target cell bodies instead of dendrites. Benavides-Piccione and DeFelipe (2007) state that the most common cell type targeted by interneurons are pyramidal cells.

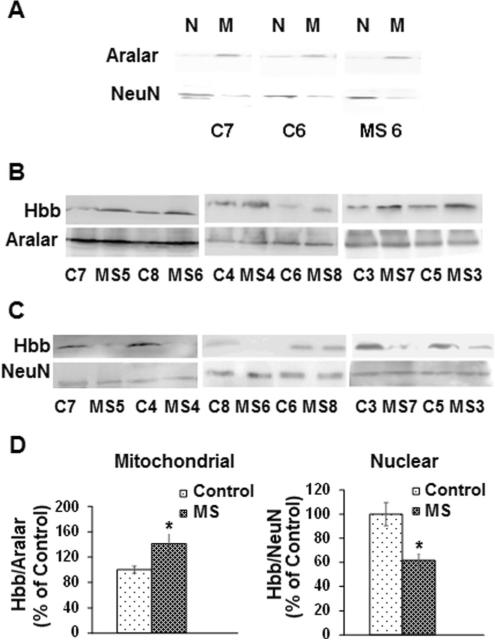

We did not observe any significant changes in the numbers of neurons expressing Hbb in MS cortex compared to controls. To determine whether levels of Hbb protein were changed between MS and control brains, we performed Western blotting with mitochondrial and nuclear protein isolated from six MS and six control cortical gray matter samples as shown in Fig. 2. The relative purity of protein fractions was determined by Western blotting with antibodies to the mitochondrial membrane protein aralar and the neuronal nuclear marker NeuN. A representative Western blot demonstrating purity of fractionation is shown in Fig. 2a for a subset of samples. Consistent with our previous study, we found that mean Hbb levels were increased by 29 % in mitochondrial fractions isolated from MS cortical samples compared to controls (Broadwater et al. 2011) (Fig. 2b, d). We also measured levels of Hbb in nuclear fractions and found that Hbb levels were reduced on average by 38 % in MS nuclear fractions compared to controls (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2.

The subcellular localization of Hbb is altered in MS samples. a Representative Western blot demonstrating the purity of mitochondrial and nuclear fractions isolated from control and MS postmortem cortical gray matter. Nuclear (N) and mitochondrial (M) fractions isolated from control and MS samples were blotted with antibodies to the neuronal nuclear marker NeuN and the mitochondrial marker aralar. b Representative Western blots for Hbb and aralar in mitochondrial fractions isolated from MS cortical samples compared to controls. c Representative Western blots for Hbb and NeuN show decreased Hbb in MS nuclear fractions compared to controls. d Quantitation shows that average Hbb levels are increased in mitochondrial fractions and decreased in nuclear fractions isolated from MS cortical gray matter compared to controls. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05

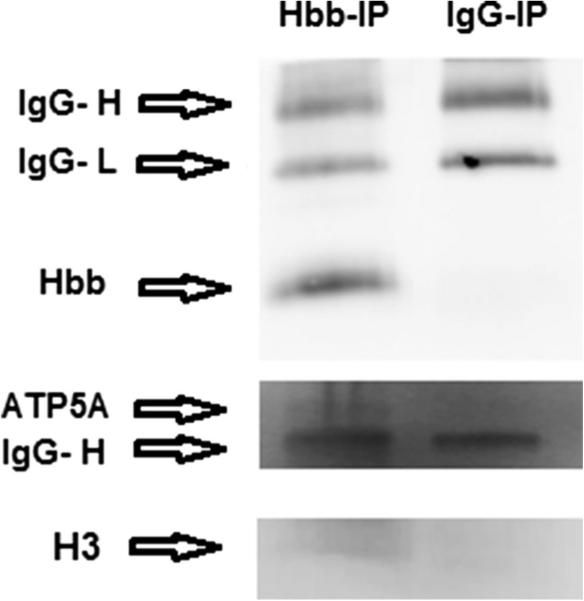

We then performed co-IP experiments with an antibody to Hbb and total cell extracts from motor cortex from an MS brain to identify proteins which interact with Hbb. Fifteen proteins including Hbb itself were identified by LC-MS/MS (p ≤ 0.05). Table 2 describes the proteins identified which coimmunoprecipitated with Hbb. All peptide sequences assigned are listed, with their respective observed and expected peptide masses and ion scores. The accession number for each protein is listed with their respective exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI), queries matched, and mass. The emPAI is a semi-quantitative estimate of the relative abundance of proteins in the sample. It is the number of peptides per protein normalized by the theoretical number of peptides. Proteins low in abundance will have low emPAI scores. Five of the Hbb interacting proteins identified in the postmortem sample were mitochondrial, including ATP synthase subunits alpha and beta (ATP5A1 and ATP5B), mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase (MDH2), ADP/ATP translocase 4 (SLC25A31), and a mitochondrial phosphate carrier (SLC25A3), suggesting that Hbb is associated with mitochondria. We also identified several histone proteins including histone H3 (HIST2H3A) and lysine-specific demethylase 8 (KDM8), which is a histone demethylase, suggesting that Hbb may be involved in regulating histone methylation. Western blotting confirmed that Hbb eluted after immunoprecipitation with the Hbb antibody as expected (Fig. 3) but Hbb did not elute after immunoprecipitation with a non-specific IgG antibody. Other Hbb interacting proteins identified by co-IP followed by LC-MS/MS including ATP5A1 and histone H3 were also confirmed by Western blot as shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Proteins interacting with Hbb identified by co-IP followed by mass spectrometry

| Protein | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P62805 | Mass, 11360 | Score, 626 | Matches, 30(30) | Sequences, 6(6) | emPAI, 7.38 | |

| Histone H4 Homo sapiens GN=HIST1H4A | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 6197 | 714.3464 | 713.3391 | 713.3385 | 39 | 0.00043 | R.TLYGFGG.- | |

| 9328 | 495.2934 | 988.5722 | 988.5706 | 49 | 0.00011 | K.VFLENVIR.D | |

| 10541 | 567.7756 | 1133.5366 | 1133.5353 | 44 | 0.00036 | R.DAVTYTEHAK.R | |

| 10865 | 590.8145 | 1179.6144 | 1179.6135 | 61 | 8.7e–006 | R.ISGLIYEETR.G | |

| 11693 | 663.3817 | 1324.7488 | 1324.7463 | 47 | 0.00015 | R.DNIQGITKPAIR.R | |

| 11698 | 663.8536 | 1325.6926 | 1325.6901 | 50 | 9.1e–005 | K.TVTAMDVVYALK.R | |

| 2 | Q6FI13 | Mass, 14087 | Score, 535 | Matches, 19(19) | Sequences, 6(6) | emPAI, 3.55 | |

| Histone H2A type 2-A Homo sapiens GN=HIST2H2AA3 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7540 | 419.2148 | 836.4150 | 836.4140 | 27 | 0.018 | R.KGNYAER.V | |

| 7851 | 425.7671 | 849.5196 | 849.5184 | 34 | 0.00064 | R.HLQLAIR.N | |

| 8013 | 431.2011 | 860.3876 | 860.3875 | 22 | 0.037 | R.NDEELNK.L | |

| 8951 | 472.7695 | 943.5244 | 943.5240 | 66 | 4.5e–006 | R.AGLQFPVGR.V | |

| 13753 | 644.3956 | 1930.1650 | 1930.1615 | 68 | 1.9e–007 | K.VTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPK.K | |

| 15856 | 983.8522 | 2948.5348 | 2948.5317 | 64 | 3.3e–006 | R.VGAGAPVYMAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAAR.D | |

| 3 | P16104 | Mass, 15135 | Score, 379 | Matches, 16(16) | Sequences, 6(6) | emPAI, 3.14 | |

| Histone H2A.x Homo sapiens GN=H2AFX | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7851 | 425.7671 | 849.5196 | 849.5184 | 34 | 0.00064 | R.HLQLAIR.N | |

| 8013 | 431.2011 | 860.3876 | 860.3875 | 22 | 0.037 | R.NDEELNK.L | |

| 8463 | 449.2010 | 896.3874 | 896.3876 | 22 | 0.019 | K.ATQASQEY.- | |

| 8951 | 472.7695 | 943.5244 | 943.5240 | 66 | 4.5e–006 | R.AGLQFPVGR.V | |

| 14651 | 1136.1930 | 2270.3714 | 2270.3726 | 53 | 5.6e–006 | K.LLGGVTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPK.K | |

| 15814 | 972.5350 | 2914.5832 | 2914.5804 | 75 | 1.3e–007 | R.VGAGAPVYLAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAAR.D | |

| 4 | P68871 | Mass, 15988 | Score, 508 | Matches, 17(17) | Sequences, 7(7) | emPAI, 2.84 | |

| Hemoglobin subunit beta Homo sapiens GN=HBB | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 8849 | 466.7641 | 931.5136 | 931.5127 | 29 | 0.016 | K.SAVTALWGK.V | |

| 9039 | 476.7588 | 951.5030 | 951.5025 | 24 | 0.032 | M.VHLTPEEK.S | |

| 10637 | 575.3421 | 1148.6696 | 1148.6666 | 40 | 0.00042 | K.VVAGVANALAHK.Y | |

| 11403 | 637.8672 | 1273.7198 | 1273.7183 | 34 | 0.0028 | R.LLVVYPWTQR.F | |

| 11629 | 657.8362 | 1313.6578 | 1313.6575 | 72 | 6e–007 | K.VNVDEVGGEALGR.L | |

| 12030 | 689.8539 | 1377.6932 | 1377.6929 | 36 | 0.0034 | K.EFTPPVQAAYQK.V | |

| 14036 | 1037.9760 | 2073.9374 | 2073.9354 | 92 | 5.2e–009 | R.FFESFGDLSTPDAVMGNPK.V | |

| 5 | Q5QNW6 | Mass, 13912 | Score, 496 | Matches, 29(29) | Sequences, 7(7) | emPAI, 6.23 | |

| Histone H2B type 2-F Homo sapiens GN=HIST2H2BF | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4201 | 585.2880 | 584.2807 | 584.2806 | 18 | 0.033 | K.YTSSK.- | |

| 7272 | 408.7325 | 815.4504 | 815.4501 | 34 | 0.0055 | R.EIQTAVR.L | |

| 7404 | 414.7150 | 827.4154 | 827.4137 | 38 | 0.00088 | K.HAVSEGTK.A | |

| 9047 | 477.3063 | 952.5980 | 952.5957 | 20 | 0.026 | R.LLLPGELAK.H | |

| 10795 | 390.2040 | 1167.5902 | 1167.5884 | 48 | 0.00016 | K.QVHPDTGISSK.A | |

| 11347 | 633.3250 | 1264.6354 | 1264.6339 | 36 | 0.0029 | R.KESYSVYVYK.V | |

| 13282 | 888.4092 | 1774.8038 | 1774.8018 | (79) | 1.1e–007 | K.AMGIMNSFVNDIFER.I | |

| 6 | Q71DI3 | Mass, 15379 | Score, 273 | Matches, 16(16) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 1.22 | |

| Histone H3.2 Homo sapiens GN=HIST2H3A | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 6224 | 715.4102 | 714.4029 | 714.4024 | 32 | 0.0088 | K.DIQLAR.R | |

| 7467 | 416.2508 | 830.4870 | 830.4861 | 64 | 4.9e–006 | K.STELLIR.K | |

| 7833 | 850.4313 | 849.4240 | 849.4232 | 50 | 0.00012 | R.EIAQDFK.T | |

| 7 | P25705 | Mass, 59714 | Score, 185 | Matches, 6(6) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.17 | |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial Homo sapiens GN=ATP5A1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 9641 | 513.8013 | 1025.5880 | 1025.5869 | 28 | 0.0095 | K.AVDSLVPIGR.G | |

| 12779 | 788.3994 | 1574.7842 | 1574.7788 | 77 | 2.6e–007 | R.ILGADTSVDLEETGR.V | |

| 12923 | 812.9507 | 1623.8868 | 1623.8832 | 50 | 8.8e–005 | R.TGAIVDVPVGEELLGR.V | |

| 8 | P40926 | Mass, 35481 | Score, 169 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.09 | |

| Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial Homo sapiens GN=MDH2 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 13347 | 897.0498 | 1792.0850 | 1792.0822 | 97 | 2e–010 | K.VAVLGASGGIGQPLSLLLK.N | |

| 9 | P06576 | Mass, 56525 | Score, 101 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.06 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial Homo sapiens GN=ATP5B | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 13877 | 994.5219 | 1987.0292 | 1987.0262 | 68 | 2.2e–006 | R.AIAELGIYPAVDPLDSTSR.I | |

| 10 | Q9H0C2 | Mass, 34999 | Score, 99 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.20 | |

| ADP/ATP translocase 4 Homo sapiens GN=SLC25A31 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7931 | 428.7490 | 855.4834 | 855.4814 | 24 | 0.017 | K.TAVAPIER.V | |

| 12294 | 723.8759 | 1445.7372 | 1445.7343 | 60 | 1.6e–005 | R.YFPTQALNFAFK.D | |

| 11 | P10412 | Mass, 21852 | Score, 90 | Matches, 7(7) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.53 | |

| Histone H1.4 Homo sapiens GN=HIST1H1E | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7180 | 406.2014 | 810.3882 | 810.3872 | 25 | 0.02 | K.GTGASGSFK.L | |

| 9215 | 487.3066 | 972.5986 | 972.5968 | 31 | 0.0036 | R.SGVSLAALKK.A | |

| 10346 | 554.2881 | 1106.5616 | 1106.5608 | 45 | 0.0005 | K.ALAAAGYDVEK.N | |

| 12 | Q00325 | Mass, 40069 | Score, 47 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.08 | |

| Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial Homo sapiens GN=SLC25A3 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 11909 | 681.3629 | 1360.7112 | 1360.7099 | 44 | 0.00063 | R.IQTQPGYANTLR.D | |

| 13 | P69905 | Mass, 15248 | Score, 41 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.22 | |

| Hemoglobin subunit alpha OS=Homo sapiens GN=HBA1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 12621 | 510.5836 | 1528.7290 | 1528.7270 | 33 | 0.0048 | K.VGAHAGEYGAEALER.M | |

| 14 | Q8N371 | Mass, 47240 | Score, 24 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.07 | |

| Lysine-specific demethylase 8 Homo sapiens GN=KDM8 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7597 | 421.7583 | 841.5020 | 841.5021 | 22 | 0.038 | K.LEKTVPR.L | |

| 15 | P0C0S8 | Mass, 14083 | Score, 92 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.54 | |

| Histone H2A type 1 Homo sapiens GN=HIST1H2AG | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 9506 | 472.7698 | 943.5250 | 943.5240 | 39 | 0.0024 | R.AGLQFPVGR.V | |

| 15653 | 972.5334 | 2914.5784 | 2914.5804 | 61 | 3.9e–006 | R.VGAGAPVYLAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAAR.D | |

| 16 | Q5QNW6 | mass, 13912 | score, 34 | matches, 3(3) | sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.55 | |

| Histone H2B type 2-F Homo sapiens GN=HIST2H2BF | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 8107 | 408.7327 | 815.4508 | 815.4501 | 33 | 0.0074 | R.EIQTAVR.L | |

| 9609 | 477.3055 | 952.5964 | 952.5957 | 18 | 0.025 | R.LLLPGELAK.H | |

Fig. 3.

Confirmation of proteins interacting with Hbb that were identified by mass spectrometry. Western blotting shows that Hbb, ATP5A1, and histone H3 were pulled down in the IP experiment with the Hbb antibody but not with the non-specific IgG antibody. Arrows denote bands for Hbb (16 kDa), ATP5A1 (55 kDa), and histone H3 (13 kDa) on separate blots. Because this protein was immunoprecipitated with an Hbb antibody, IgG heavy and light chains (IgG-H and IgG-L) are present at 50 and ~25 kDa

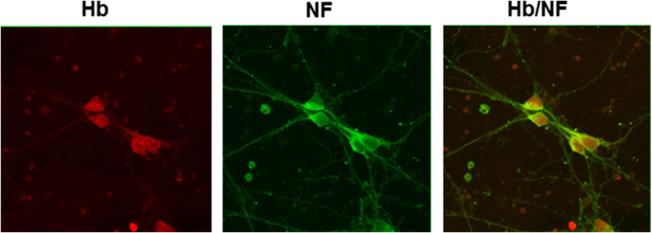

Because the protein isolated from the human postmortem cortical sample would contain protein not only from neurons but also from other cell types that express hemoglobin including red blood cells, vascular endothelial cells, and macrophages, we repeated the co-IP combined with LC-MS/MS with total protein isolated from cultured rat primary neurons. It has been reported previously that primary neurons express hemoglobin (Schelshorn et al. 2009). To confirm that our cultured neurons expressed hemoglobin, we first performed immunofluorescent staining with hemoglobin and neurofilament antibodies. Confocal images in Fig. 4 show that hemoglobin (Hb) and neurofilament (NF) are co-expressed in these cells. Neuron-specific hemoglobin interacting proteins identified by LC-MS/MS are shown in Table 3 and are consistent with those identified in the human postmortem cortical gray matter sample. Hemoglobin interacting proteins in rat primary neurons overlapped with many of the mitochondrial and nuclear proteins identified in the postmortem sample including Atp5a1, Atp5b, Mdh2, Slc25a3, and histones (Table 3). We also identified 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase in primary neurons which is of interest since many histone demethylases require 2-oxoglutarate as a cofactor (Gut and Verdin 2013; Salminen et al. 2014). These data provide further evidence that hemoglobin may be involved in mediating signals between mitochondria and the nucleus in neurons.

Fig. 4.

Hemoglobin is expressed in cultured rat primary neurons. Cultured neuronal cells were immunostained with antibodies to hemoglobin (Hb) and neurofilament (NF). The merged image shows Hb (red fluorescence) and NF (green fluorescence) colocalization

Table 3.

Proteins interacting with hemoglobin in cultured primary neurons

| Protein | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P02091 | Mass, 15969 | Score, 4251 | Matches, 126(126) | Sequences, 14(14) | emPAI, 121.67 | |

| Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 Rattus norvegicus GN=Hbb | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5761 | 739.4104 | 738.4031 | 738.4024 | 28.51 | 0.0025 | HLDNLK | |

| 8065 | 912.4783 | 911.471 | 911.4712 | 43.63 | 0.0001 | VHLTDAEK | |

| 8111 | 458.2562 | 914.4978 | 914.4974 | 45.01 | 0.00012 | AAVNGLWGK | |

| 9911 | 1090.589 | 1089.5817 | 1089.5818 | 53.78 | 2.30E–05 | VINAFNDGLK | |

| 10208 | 561.8355 | 1121.6564 | 1121.6557 | 71.86 | 6.80E–08 | VVAGVASALAHK | |

| 10248 | 563.786 | 1125.5574 | 1125.5567 | 28.79 | 0.005 | LHVDPENFR | |

| 10938 | 609.8459 | 1217.6772 | 1217.6768 | 72.89 | 2.20E–07 | KVINAFNDGLK | |

| 11335 | 637.8666 | 1273.7186 | 1273.7183 | 51.57 | 1.90E–05 | LLVVYPWTQR | |

| 11482 | 649.8201 | 1297.6256 | 1297.6263 | 75.84 | 8.30E–08 | VNPDDVGGEALGR | |

| 12152 | 699.33 | 1396.6454 | 1396.6445 | 58.4 | 4.10E–06 | EFTPCAQAAFQK | |

| 12274 | 711.897 | 1421.7794 | 1421.7779 | 63.1 | 1.60E–06 | VVAGVASALAHKYH | |

| 12695 | 505.5738 | 1513.6996 | 1513.6984 | 27.73 | 0.0054 | GTFAHLSELHCDK | |

| 13339 | 572.0121 | 1713.0145 | 1713.0124 | 39.19 | 0.00012 | LLGNMIVIVLGHHLGK | |

| 14257 | 1011.959 | 2021.9034 | 2021.9041 | 109.26 | 2.30E–11 | YFDSFGDLSSASAIMGNPK | |

| 2 | P11517 | Mass, 15972 | Score, 2095 | Matches 85(85) | Sequences, 13(13) | emPAI, 67.88 | |

| Hemoglobin subunit beta-2 Rattus norvegicus GN = Hbb2 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5761 | 739.4104 | 738.4031 | 738.4024 | 28.51 | 0.0025 | HLDNLK | |

| 8065 | 912.4783 | 911.471 | 911.4712 | 43.63 | 0.0001 | VHLTDAEK | |

| 8155 | 459.7562 | 917.4978 | 917.4971 | 41.46 | 0.00029 | ATVSGLWGK | |

| 9911 | 1090.589 | 1089.5817 | 1089.5818 | 53.78 | 2.30E–05 | VINAFNDGLK | |

| 10208 | 561.8355 | 1121.6564 | 1121.6557 | 71.86 | 6.80E–08 | VVAGVASALAHK | |

| 10248 | 563.786 | 1125.5574 | 1125.5567 | 28.79 | 0.005 | LHVDPENFR | |

| 10938 | 609.8459 | 1217.6772 | 1217.6768 | 72.89 | 2.20E–07 | KVINAFNDGLK | |

| 11335 | 637.8666 | 1273.7186 | 1273.7183 | 51.57 | 1.90E–05 | LLVVYPWTQR | |

| 12152 | 699.33 | 1396.6454 | 1396.6445 | 58.4 | 4.10E–06 | EFTPCAQAAFQK | |

| 12274 | 711.897 | 1421.7794 | 1421.7779 | 63.1 | 1.60E–06 | VVAGVASALAHKYH | |

| 12695 | 505.5738 | 1513.6996 | 1513.6984 | 27.73 | 0.0054 | GTFAHLSELHCDK | |

| 13339 | 572.0121 | 1713.0145 | 1713.0124 | 39.19 | 0.00012 | LLGNMIVIVLGHHLGK | |

| 13377 | 861.4307 | 1720.8468 | 1720.8454 | 93.58 | 1.80E–09 | FGDLSSASAIMGNPQVK | |

| 3 | P01946 | Mass, 15319 | Score, 1878 | Matches, 90(90) | Sequences, 12(12) | emPAI, 43.93 | |

| Hemoglobin subunit alpha-1/2 Rattus norvegicus GN=Hba1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4787 | 664.287 | 663.2797 | 663.2799 | 32.22 | 0.0006 | NCWGK | |

| 5884 | 747.3885 | 746.3812 | 746.381 | 33.47 | 0.0018 | VLSADDK | |

| 6652 | 408.2531 | 814.4916 | 814.4912 | 42.8 | 0.00015 | KVADALAK | |

| 6708 | 818.4412 | 817.4339 | 817.4334 | 24.04 | 0.028 | VDPVNFK | |

| 9269 | 515.2577 | 1028.5008 | 1028.5001 | 45.21 | 6.30E–05 | MFAAFPTTK | |

| 9852 | 544.3166 | 1086.6186 | 1086.6186 | 37.59 | 0.00065 | LRVDPVNFK | |

| 10821 | 602.3326 | 1202.6506 | 1202.6507 | 65.56 | 1.20E–06 | VLSADDKTNIK | |

| 11189 | 626.8617 | 1251.7088 | 1251.7075 | 89.05 | 2.80E–09 | FLASVSTVLTSK | |

| 12934 | 786.8738 | 1571.733 | 1571.7328 | 62.23 | 1.50E–06 | IGGHGGEYGEEALQR | |

| 13410 | 868.4362 | 1734.8578 | 1734.8577 | 68.85 | 7.30E–07 | TYFSHIDVSPGSAQVK | |

| 15156 | 575.0444 | 2296.1485 | 2296.1448 | 46.15 | 0.00013 | AADHVEDLPGALSTLSDLHAHK | |

| 4 | Q00715 | Mass, 13982 | Score, 1255 | Matches, 51(51) | Sequences, 7(7) | emPAI, 16.05 | |

| Histone H2B type 1 Rattus norvegicus | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4797 | 664.3625 | 663.3552 | 663.3551 | 18.43 | 0.045 | STITSR | |

| 6686 | 408.733 | 815.4514 | 815.4501 | 34.7 | 0.0016 | EIQTAVR | |

| 6842 | 414.7141 | 827.4136 | 827.4137 | 42.55 | 9.70E–05 | HAVSEGTK | |

| 8548 | 477.3055 | 952.5964 | 952.5957 | 38.11 | 0.00015 | LLLPGELAK | |

| 10592 | 390.2036 | 1167.589 | 1167.5884 | 43.65 | 0.00016 | QVHPDTGISSK | |

| 11281 | 633.3248 | 1264.635 | 1264.6339 | 29.56 | 0.0053 | KESYSVYVYK | |

| 13451 | 872.414 | 1742.8134 | 1742.812 | 97.35 | 5.60E–10 | AMGIMNSFVNDIFER | |

| 5 | P62804 | Mass, 11360 | Score, 1181 | Matches, 45(45) | Sequences, 7(7) | emPAI, 9.93 | |

| Histone H4 Rattus norvegicus GN = Hist1h4b | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5547 | 714.3456 | 713.3383 | 713.3385 | 41.44 | 8.30E–05 | TLYGFGG | |

| 8883 | 495.2927 | 988.5708 | 988.5706 | 45.7 | 7.70E–05 | VFLENVIR | |

| 10315 | 567.7753 | 1133.536 | 1133.5353 | 37.2 | 0.00065 | DAVTYTEHAK | |

| 10681 | 590.8146 | 1179.6146 | 1179.6135 | 78.4 | 5.60E–08 | ISGLIYEETR | |

| 11608 | 655.8549 | 1309.6952 | 1309.6952 | 62.61 | 1.80E–06 | TVTAMDVVYALK | |

| 11721 | 663.3807 | 1324.7468 | 1324.7463 | 43.17 | 9.60E–05 | DNIQGITKPAIR | |

| 11734 | 663.8532 | 1325.6918 | 1325.6901 | 62.95 | 1.60E–06 | TVTAMDVVYALK | |

| 12498 | 489.6064 | 1465.7974 | 1465.7963 | 19.35 | 0.037 | TVTAMDVVYALKR | |

| 6 | P15865 | Mass, 21974 | Score, 926 | Matches, 52(52) | Sequences, 7(7) | emPAI, 2.59 | |

| Histone H1.4 Rattus norvegicus GN=Hist1h1e | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 6256 | 392.7374 | 783.4602 | 783.4603 | 37.95 | 0.00016 | KPAAAAGAK | |

| 7669 | 437.7536 | 873.4926 | 873.492 | 38.94 | 0.00059 | KATGTATPK | |

| 8763 | 487.3064 | 972.5982 | 972.5968 | 19.54 | 0.019 | SGVSLAALKK | |

| 10082 | 554.2875 | 1106.5604 | 1106.5608 | 56.04 | 9.00E–06 | ALAAAGYDVEK | |

| 10792 | 599.838 | 1197.6614 | 1197.6605 | 58.95 | 4.80E–06 | ASGPPVSELITK | |

| 11737 | 442.9258 | 1325.7556 | 1325.7554 | 32.4 | 0.0016 | KASGPPVSELITK | |

| 7 | P0C169 | Mass, 14097 | Score, 718 | Matches, 23(23) | Sequences, 5(5) | emPAI, 3.55 | |

| Histone H2A type 1-C Rattus norvegicus | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 1567 | 425.7671 | 849.5196 | 849.5184 | 23.42 | 0.0045 | HLQLAIR | |

| 1733 | 431.2012 | 860.3878 | 860.3875 | 20.32 | 0.014 | NDEELNK | |

| 3261 | 472.7701 | 943.5256 | 943.524 | 67.07 | 1.20E–06 | AGLQFPVGR | |

| 18687 | 966.0891 | 1930.1636 | 1930.1615 | 78.59 | 1.40E–08 | VTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPK | |

| 25442 | 972.5353 | 2914.5841 | 2914.5804 | 74.31 | 8.20E–08 | VGAGAPVYLAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAAR | |

| 8 | P0CC09 | Mass, 14087 | Score, 671 | Matches, 22(22) | Sequences, 5(5) | emPAI, 3.55 | |

| Histone H2A type 2-A Rattus norvegicus GN=Hist2h2aa3 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 1567 | 425.7671 | 849.5196 | 849.5184 | 23.42 | 0.0045 | HLQLAIR | |

| 1733 | 431.2012 | 860.3878 | 860.3875 | 20.32 | 0.014 | NDEELNK | |

| 3261 | 472.7701 | 943.5256 | 943.524 | 67.07 | 1.20E–06 | AGLQFPVGR | |

| 18687 | 966.0891 | 1930.1636 | 1930.1615 | 78.59 | 1.40E–08 | VTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPK | |

| 25613 | 983.8522 | 2948.5348 | 2948.5317 | 86.85 | 6.90E–09 | VGAGAPVYMAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAAR | |

| 9 | P04797 | Mass, 35805 | Score, 501 | Matches, 10(10) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.3 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Rattus norvegicus GN=Gapdh | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 10287 | 685.3768 | 1368.739 | 1368.7361 | 72.08 | 2.00E–07 | GAAQNIIPASTGAAK | |

| 11027 | 778.9102 | 1555.8058 | 1555.8029 | 100.14 | 3.50E–10 | VPTPNVSVVDLTCR | |

| 12207 | 910.4582 | 1818.9018 | 1818.8968 | 59.72 | 5.70E–06 | IVSNASCTTNCLAPLAK | |

| 10 | Q00729 | Mass, 14216 | Score, 482 | Matches, 39(39) | Sequences, 5(5) | emPAI, 5.92 | |

| Histone H2B type 1-A Rattus norvegicus GN=Hist1h2ba | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4797 | 664.3625 | 663.3552 | 663.3551 | 18.43 | 0.045 | STITSR | |

| 6686 | 408.733 | 815.4514 | 815.4501 | 34.7 | 0.0016 | EIQTAVR | |

| 6842 | 414.7141 | 827.4136 | 827.4137 | 42.55 | 9.70E–05 | HAVSEGTK | |

| 8548 | 477.3055 | 952.5964 | 952.5957 | 38.11 | 0.00015 | LLLPGELAK | |

| 10592 | 390.2036 | 1167.589 | 1167.5884 | 43.65 | 0.00016 | QVHPDTGISSK | |

| 11 | Q06647 | Mass, 23383 | Score, 446 | Matches, 21(21) | Sequences, 8(8) | emPAI, 2.8 | |

| ATP synthase subunit O, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Atp5o | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 9061 | 504.7904 | 1007.5662 | 1007.5651 | 22.49 | 0.0096 | TVLNSFLSK | |

| 10374 | 573.2957 | 1144.5768 | 1144.5764 | 24.79 | 0.014 | YATALYSAASK | |

| 10909 | 608.8688 | 1215.723 | 1215.7227 | 62.75 | 9.30E–07 | VSLAVLNPYIK | |

| 11586 | 654.8181 | 1307.6216 | 1307.6214 | 26.26 | 0.0084 | TDPSIMGGMIVR | |

| 12974 | 528.3076 | 1581.901 | 1581.8991 | 37.98 | 0.00029 | LVRPPVQVYGIEGR | |

| 13903 | 938.9837 | 1875.9528 | 1875.9512 | 50.08 | 4.90E–05 | FSPLTANLMNLLAENGR | |

| 14291 | 678.6865 | 2033.0377 | 2033.0364 | 35.54 | 0.0015 | LGNTQGVISAFSTIMSVHR | |

| 15335 | 1188.604 | 2375.1934 | 2375.193 | 64.91 | 1.60E–06 | GEVPCTVTTAFPLDEAVLSELK | |

| 12 | P15999 | Mass, 59717 | Score, 358 | Matches, 12(12) | Sequences, 5(5) | emPAI, 0.38 | |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Atp5a1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5733 | 423.2588 | 844.503 | 844.5018 | 38.23 | 0.00071 | STVAQLVK | |

| 6124 | 439.217 | 876.4194 | 876.4189 | 31.77 | 0.0027 | ISEQSDAK | |

| 8969 | 586.3209 | 1170.6272 | 1170.6245 | 51.74 | 2.50E–05 | VVDALGNAIDGK | |

| 10146 | 668.8441 | 1335.6736 | 1335.6711 | 44.06 | 0.00019 | EIVTNFLAGFEP | |

| 11081 | 788.3985 | 1574.7824 | 1574.7788 | 75.59 | 1.10E–07 | ILGADTSVDLEETGR | |

| 13 | Q6LED0 | Mass, 15394 | Score, 338 | Matches, 23(23) | Sequences, 4(4) | emPAI, 2.3 | |

| Histone H3.1 Rattus norvegicus | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5576 | 715.4102 | 714.4029 | 714.4024 | 34.16 | 0.0016 | DIQLAR | |

| 6889 | 416.2504 | 830.4862 | 830.4861 | 50.19 | 4.10E–05 | STELLIR | |

| 7256 | 850.431 | 849.4237 | 849.4232 | 49.8 | 3.90E–05 | EIAQDFK | |

| 9295 | 516.8012 | 1031.5878 | 1031.5876 | 21.29 | 0.023 | YRPGTVALR | |

| 14 | P63039 | Mass, 60917 | Score, 288 | Matches, 7(7) | Sequences, 4(4) | emPAI, 0.3 | |

| 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Hspd1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 8933 | 617.3018 | 1232.589 | 1232.5885 | 51.45 | 2.80E–05 | VGGTSDVEVNEK | |

| 20403 | 715.7147 | 2144.1223 | 2144.1221 | 56.51 | 8.50E–06 | ALMLQGVDLLADAVAVTMGPK | |

| 22880 | 818.796 | 2453.3662 | 2453.3629 | 60.62 | 1.40E–06 | TALLDAAGVASLLTTAEAVVTEIPK | |

| 25108 | 947.5204 | 2839.5394 | 2839.543 | 62.63 | 9.30E–07 | TALLDAAGVASLLTTAEAVVTEIPKEEK | |

| 15 | P0C0S7 | Mass, 13545 | Score, 272 | Matches, 13(13) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.96 | |

| Histone H2A.Z Rattus norvegicus GN=H2afz | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7274 | 425.767 | 849.5194 | 849.5184 | 29.45 | 0.0011 | HLQLAIR | |

| 8476 | 472.7698 | 943.525 | 943.524 | 59.27 | 7.80E–06 | AGLQFPVGR | |

| 10178 | 559.7829 | 1117.5512 | 1117.5503 | 41.73 | 0.00033 | GDEELDSLIK | |

| 16 | Q09073 | Mass, 32880 | Score, 164 | Matches, 6(6) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.33 | |

| ADP/ATP translocase 2 Rattus norvegicus GN=Slc25a5 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 7335 | 428.7483 | 855.482 | 855.4814 | 35.07 | 0.0005 | TAVAPIER | |

| 10954 | 610.3386 | 1218.6626 | 1218.6608 | 43.09 | 0.00017 | DFLAGGVAAAISK | |

| 12409 | 723.8749 | 1445.7352 | 1445.7343 | 63.47 | 2.20E–06 | YFPTQALNFAFK | |

| 17 | P04636 | Mass, 35661 | Score, 161 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.19 | |

| Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Mdh2 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5833 | 537.2957 | 1072.5768 | 1072.5764 | 28.28 | 0.007 | IQEAGTEVVK | |

| 16994 | 897.0486 | 1792.0826 | 1792.0822 | 93.25 | 4.70E–10 | VAVLGASGGIGQPLSLLLK | |

| 18 | P10719 | Mass, 56318 | Score, 119 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.12 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN = Atp5b | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 12349 | 718.3795 | 1434.7444 | 1434.7467 | 55.6 | 1.50E–05 | FTQAGSEVSALLGR | |

| 14162 | 994.5206 | 1987.0266 | 1987.0262 | 59.15 | 5.00E–06 | AIAELGIYPAVDPLDSTSR | |

| 8952 | 499.2514 | 996.4882 | 996.4876 | 35.02 | 0.00077 | LSYNTASNK | |

| 19 | Q3KR86 | Mass, 67135 | Score, 82 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 3(3) emPAI, 0.15 | ||

| Mitochondrial inner membrane protein (Fragment) Rattus norvegicus GN=Immt | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 702 | 404.714 | 807.4134 | 807.4127 | 27.88 | 0.0064 | AFDSAVAK | |

| 5879 | 538.2546 | 1074.4946 | 1074.4941 | 33.7 | 0.00083 | SEIQAEQDR | |

| 8883 | 616.2936 | 1230.5726 | 1230.5728 | 52.8 | 1.20E–05 | YSTSSSSGVTAGK | |

| 20 | P19527 | Mass, 61298 | Score, 74 | Matches, 6(6) | Sequences, 4(4) | emPAI, 0.23 | |

| Neurofilament light polypeptide Rattus norvegicus GN=Nefl | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 1996 | 437.2246 | 872.4346 | 872.4352 | 28.26 | 0.0043 | GADEAALAR | |

| 4401 | 501.759 | 1001.5034 | 1001.5029 | 34.67 | 0.0012 | QLQELEDK | |

| 5557 | 531.2589 | 1060.5032 | 1060.5036 | 30.6 | 0.0033 | LAAEDATNEK | |

| 6814 | 561.2956 | 1120.5766 | 1120.5764 | 22.84 | 0.025 | EYQDLLNVK | |

| 21 | P16036 | Mass: 39419 | Score:70 | Matches: 2(2) | Sequences: 1(1) | emPAI, 0.08 | |

| Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN = Slc25a3 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5301 | 523.7833 | 1045.552 | 1045.5516 | 42.38 | 0.00031 | GSTASQVLQR | |

| 5302 | 523.7834 | 1045.5522 | 1045.5516 | 47.53 | 9.20E–05 | GSTASQVLQR | |

| 22 | P48721 | Mass, 73812 | Score, 59 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.09 | |

| Stress-70 protein, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN = Hspa9 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4786 | 510.7329 | 1019.4512 | 1019.452 | 31.29 | 0.0014 | DSETGENIR | |

| 8885 | 616.3359 | 1230.6572 | 1230.6568 | 45.12 | 0.00015 | QAASSLQQASLK | |

| 23 | D3ZAF6 | Mass, 10446 | Score, 58 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.33 | |

| ATP synthase subunit f, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Atp5j2 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 11091 | 619.8123 | 1237.61 | 1237.6091 | 35.17 | 0.0011 | DFTPSGIAGAFR | |

| 24 | P12839 | Mass, 95734 | Score, 50 | Matches, 5(5) | Sequences, 3(3) | emPAI, 0.11 | |

| Neurofilament medium polypeptide Rattus norvegicus GN=Nefm | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 1541 | 424.7401 | 847.4656 | 847.4651 | 34.19 | 0.0021 | TDISTALK | |

| 6814 | 561.2956 | 1120.5766 | 1120.5764 | 22.84 | 0.025 | EYQDLLNVK | |

| 11986 | 469.209 | 1404.6052 | 1404.6045 | 20.82 | 0.014 | VEEHEETFEEK | |

| 25 | Q5XI78 | Mass, 116221 | Score, 50 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) emPAI, 0.03 | ||

| 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Ogdh | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 15230 | 830.4722 | 1658.9298 | 1658.9283 | 39.81 | 0.00024 | IEQLSPFPFDLLLK | |

| 26 | Q9ER34 | Mass, 85380 | Score, 50 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.08 | |

| Aconitate hydratase, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Aco2 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 4084 | 494.7566 | 987.4986 | 987.4985 | 33.57 | 0.0018 | VDVSPTSQR | |

| 5713 | 534.2777 | 1066.5408 | 1066.5407 | 22.74 | 0.014 | NTIVTSYNR | |

| 27 | D3ZBN0 | Mass, 22635 | Score, 43 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.32 | |

| Histone H1.5 Rattus norvegicus GN=Hist1h1b | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 8274 | 547.2804 | 1092.5462 | 1092.5451 | 28.01 | 0.0055 | ALAAGGYDVEK | |

| 9390 | 606.8467 | 1211.6788 | 1211.6761 | 24.64 | 0.0077 | ATGPPVSELITK | |

| 28 | P17764 | Mass, 44666 | Score, 42 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.07 | |

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, mitochondrial Rattus norvegicus GN=Acat1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 13965 | 815.1015 | 2442.2827 | 2442.2835 | 30.5 | 0.0028 | IAAFADAAVDPIDFPLAPAYAVPK | |

| 29 | Q63617 | Mass, 111220 | Score, 42 | Matches, 3(3) | Sequences, 2(2) | emPAI, 0.06 | |

| Hypoxia up-regulated protein 1 Rattus norvegicus GN=Hyou1 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 5477 | 529.2618 | 1056.509 | 1056.5087 | 25 | 0.0062 | EVEEEPGLR | |

| 13694 | 768.4272 | 1534.8398 | 1534.8395 | 27.72 | 0.0053 | DAVIYPILVEFTR | |

| 30 | Q05962 | Mass, 32968 | Score, 33 | Matches, 2(2) | Sequences, 1(1) | emPAI, 0.1 | |

| ADP/ATP translocase 1 Rattus norvegicus GN=Slc25a4 | |||||||

| Query | Observed | Mr(expt) | Mr(calc) | Score | Expect | Peptide | |

| 1634 | 428.7482 | 855.4818 | 855.4814 | 26.28 | 0.0038 | TAVAPIER | |

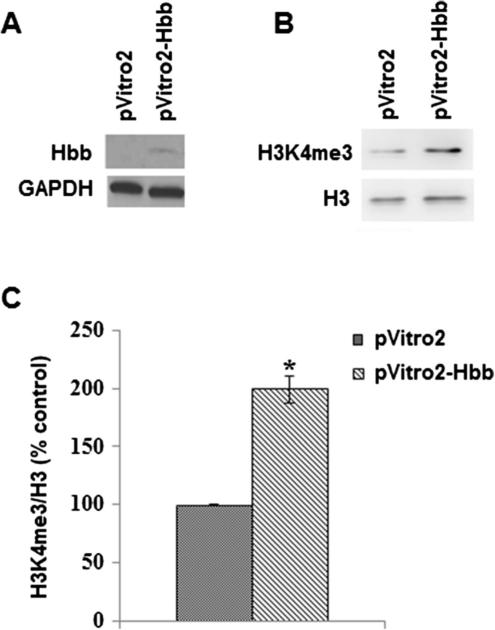

To test whether Hbb could be regulating histone methylation, we transfected human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, which do not express endogenous Hbb, with either the empty expression vector (pVitro2) or expression vector driving Hbb expression (pVitro2-Hbb) and measured histone H3 methylation. After 48 h, cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were isolated. Western blotting was performed with cytoplasmic protein and an antibody to Hbb to show that Hbb was being expressed from the pVitro2-Hbb expression construct in the neuroblastoma cells after transfection (Fig. 5a). We then performed Western blotting with nuclear extracts and an antibody to H3K4me3 and found that levels of this methylated histone were increased by almost twofold in pVitro2-Hbb transfected cells after normalization to histone H3 levels (Fig. 5b, c).

Fig. 5.

Hbb expression regulates histone H3 trimethylation. a Western blotting shows that the Hbb subunit is expressed in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pVitro2-Hbb. b Representative Western blot demonstrates that levels of H3K4me3 are increased in nuclear extracts isolated from SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pVitro2-Hbb compared to control cells transfected with vector alone. c Quantitation for H3K4me3 levels in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with either empty vector pVitro2 or pVitro2-Hbb was performed by densitometry from two separate experiments. Error bars represent SEM, *p < 0.05

Discussion

The presence of hemoglobin mRNA and protein within neuronal cells of the rodent and human CNS has been confirmed in several studies (Richter et al. 2009; Biagoli et al. 2009; Schelshorn et al. 2009; Broadwater et al. 2011), but the function of hemoglobin in cortical neurons is still not clear. Hemoglobin may serve a direct role in delivering oxygen to mitochondria in neurons. The association of hemoglobin with mitochondria is consistent with such a role (Shephard et al. 2014). However, hemoglobin may also have other functions in neurons. In order to better understand the role of hemoglobin in the CNS and its relevance to MS pathology, we first examined the cortical distribution of Hbb and its expression relative to the neuronal marker SMI32 in postmortem MS cortical tissue. The cerebral cortex can be subdivided anatomically into six layers based on the types of neurons within each layer and organization of their projections. Layer I contains almost no neurons. Cortical layers II and III contain neurons which form intracortical connections, projecting to other cortical neurons either in the same hemisphere or to the opposite hemisphere through the corpus callosum. Layer IV receives input from the thalamus, and neurons in layers V and VI project for the most part to subcortical regions including the spinal cord (DeFelipe and Farinas 1992). We found that the majority of neurons that contained Hbb and SMI32 appeared to be pyramidal neurons. Pyramidal neurons are glutamatergic and can be identified by their large size, apical dendrites, long axons, and pyramidal shape. They are generally found in cortical layers III and V but are also occasionally located in others layers. Hbb immunoreactivity in these cells was strongest in the cell body but weak staining also appeared in the nucleus and was absent in the nucleolus. These data are consistent with the study by Richter et al. 2009 which found hemoglobin immunoreactivity in cortical pyramidal neurons in rodent and human brains and the Biagoli et al. (2009) study which also reported hemoglobin expression in the cytoplasm and nucleus, but not in the nucleolus, in dopaminergic neurons.

Nonpyramidal cells are generally short axon cells which reside in middle layers of the cortex and are often inhibitory, signaling through GABAergic neurotransmission. Many of these interneurons synthesize TH. In contrast to a study by Biagoli et al. (2009), who found hemoglobin expression in TH containing neurons in the substantia nigra, we did not find any colocalization of TH and Hbb, but we did find that TH labeled neurons appeared to synapse to the soma of Hbb containing cells. This observation was consistent with the fact that TH labeled interneurons have been shown to preferentially synapse with pyramidal cells (Benevides-Piccione and DeFelipe 2007). The discrepancy between our study and the Biagoli et al. (2009) study is most likely due to the brain regions analyzed. We analyzed TH and Hbb colocalization in interneurons in the cortex while the Biagoli study analyzed deeper structures including mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons.

The significance of the increased distribution of Hbb expressing pyramidal neurons in internal cortical layers is not clear, but it may be a result of the large size and axonal projections of these cells. Neurons with longer projections require increased ATP to maintain ion homeostasis and conduction of nerve impulses over long distances. Our data show that Hbb overexpression in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells increased H3K4me3, a histone mark that is present in actively transcribed regions of chromatin and regulates expression of oxidative phosphorylation genes (Singhal et al. 2015). A role for hemoglobin in mitochondrial respiration is supported by a study by Biagoli et al. (2009) which suggested that alterations in hemoglobin expression affect cellular energetics, since dopaminergic cell lines over expressing α- and β-globin subunits exhibited changes in oxygen homeostasis and alterations in the expression of mitochondrial genes. One explanation for the enrichment of Hbb expression in projection neurons in deeper cortical layers could be to maintain an adequate supply of ATP by upregulating H3K4me3 and expression of genes necessary for oxidative phosphorylation.

Our data suggest that changes in Hbb subcellular localization may contribute to MS pathology by exacerbating the effects of demyelination on neuronal energetics. Pyramidal cells in deeper cortical layers (layers V and VI) project to subcortical regions including the thalamus and spinal cord. As a result of the longer distances these axons traverse, they are more likely to be exposed to inflammatory insults and demyelination. Axons that are demyelinated redistribute sodium channels in order to maintain conductivity (England et al. 1991; Waxman 2006). As a result, these neurons require additional ATP in order to maintain ion homeostasis and neurotransmission. In addition to metabolic stress induced by demyelination, neurons are further compromised in MS by a dysregulation of mitochondrial genes and impaired energetics. Mitochondrial abnormalities including decreased expression of nuclear encoded electron transport chain subunit genes, the neuronal mitochondrial metabolite N-acetylaspartate, and the mitochondrial biogenesis factor PPARGC1a have been reported in cortical neurons in MS in studies analyzing postmortem tissue even in areas with no overt pathology (Witte et al. 2013; Li et al. 2013). Indications of metabolic changes and a dysfunction of mitochondrial respiration in MS cortical gray matter have also been observed in vivo in magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies (Ge et al. 2004; Cader et al. 2007). Our data suggest that there is a change in Hbb subcellular localization in MS, with increased Hbb in mitochondria and decreased Hbb in the nucleus. A dysregulation of Hbb transport into the nucleus in pyramidal neurons in MS may lead to a reduction in H3K4me3 and decreased expression of genes involved in mitochondrial respiration. This mechanism may contribute to the previously reported reductions in H3K4me3 and decreased expression of mitochondrial respiratory complexes in MS cortical neurons (Singhal et al. 2015; Dutta et al. 2006). Depletion of nuclear Hbb in MS may lead to an inability for neurons to meet the increased demands for energy as a result of demyelination.

It is not clear how Hbb is regulating methylation of H3K4me3 but it is known that histone H3 demethylases are dioxygenases that can be regulated by mitochondrial metabolites (Salminen et al. 2014; Gut and Verdin 2013). These dioxygenases catalyze the oxidation of carbon-hydrogen bonds and require O2 (Vissers et al. 2014). Since one of the main functions of hemoglobin is to bind O2, it may regulate histone H3 methylation by sequestering oxygen from histone demethylases, preventing the dioxygenase reaction and histone demethylation. We found that overexpressing Hbb alone increased H3K4me3 suggesting that although in erythrocytes the α- and β subunits function as a heterotetramer, these genes may have evolved separate functions and may act independent from one another in some cells. This idea is consistent with data showing that only Hba is expressed in vascular endothelial cells where it participates in a dioxygenase reaction which regulates NO release independent of Hbb (Straub et al. 2012). Hbb can also form a tetramer (HbH) which has a higher binding affinity for O2 than the α2β2 heterotetramer (Bellelli et al. 2006). Similarly, Hbb may act independently from Hba in cortical pyramidal cells and may provide a mechanism to regulate histone demethylation, chromatin conformation, and gene expression in response to changes in cellular metabolism and O2 consumption.

We have found that Hbb is expressed in cortical pyramidal neurons and is enriched in internal cortical layers in MS. We have also found that Hbb interacts with subunits of ATP synthase, an ADP/ATP translocase, histones, and a histone lysine demethylase. Overexpression of Hbb in SH-SY5Y cells increased levels of trimethylated histone H3. Taken together these data suggest that Hbb may be a part of a mechanism linking mitochondrial energetics with epigenetic changes to histones and gene expression changes in the nucleus.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Rocky Mountain MS Center which is funded by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Brain and Spinal Cord Resource Center at UCLA for tissue. This research was partially funded by NIH Grant R21NS075645 (JM and EF) and from funds from the College of Arts and Sciences at Kent State University (JM).

References

- Bellelli A, Brunori M, Miele AE, Panetta G, Vallone B. The allosteric properties of hemoglobin: insights from natural and site directed mutants. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2006;7:17–45. doi: 10.2174/138920306775474121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Piccione R, DeFelipe J. Distribution of neurons expressing tyrosine hydroxylase in the human cerebral cortex. J Anat. 2007;211(2):212–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagioli M, Pinto M, Cesselli D, Zaninello M, Lazarevic D, Roncaglia P, Simone R, Vlachouli C, Plessy C, Bertin N, Beltrami A, Kobayashi K, Gallo V, Santoro C, Ferrer I, Rivella S, Beltrami CA, Carninci P, Raviola E, Gustincich S. Unexpected expression of α- and β-globin in mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons and glial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15454–15459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjartmar C, Kidd G, Mörk S, Rudick R, Trapp BD. Neurological disability correlates with spinal cord axonal loss and reduced N-acetyl-aspartate in chronic multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bö L, Geurts JJ, Mörk SJ, van der Valk P. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2006;183:48–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadwater L, Pandit A, Azzam S, Clements R, Vadnal J, Yong VW, Freeman EJ, Gregory RB, McDonough J. Analysis of the mitochondrial proteome in multiple sclerosis cortex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cader S, Johansen-Berg H, Wylezinska M, Palace J, Behrens TE, Smith S, Matthews PM. Discordant white matter N-acetylasparate and diffusion MRI measures suggest that chronic metabolic dys-function contributes to axonal pathology in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2007;36(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Farinas I. The pyramidal neuron of the cerebral cortex: morphological and chemical characteristics of the synaptic inputs. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;39(6):563–607. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano N, Narayanan S, Francis GS, Arnaoutelis R, Tartaglia MC, Antel JP, Matthews PM, Arnold DL. Evidence of axonal damage in the early stages of multiple sclerosis and its relevance to disability. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(1):65–70. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, McDonough J, Yin X, Peterson J, Chang A, Torres T, Gudz T, Macklin WB, Lewis DA, Fox RJ, Rudick R, Mirnics K, Trapp BD. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:478–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JD, Gamboni F, Levinson SR. Increased numbers of sodium channels form along demyelinated axons. Brain Res. 1991;548(1-2):334–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91144-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Rudick RA. Gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(3):255–65. doi: 10.1002/ana.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Gonen O, Inglese M, Babb JS, Markowitz CE, Grossman RI. Neuronal cell injury precedes brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(4):624–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut P, Verdin E. The nexus of chromatin regulation and intermediary metabolism. Nature. 2013;502(7472):489–98. doi: 10.1038/nature12752. doi:10.1038/nature12752, Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese M, Ge Y, Filippi M, Falini A, Grossman RI, Gonen O. Indirect evidence for early widespread gray matter involvement in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1825–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Clements R, Sulak M, Gregory R, Freeman E, McDonough J. Decreased NAA in gray matter is correlated with decreased availability of acetate in white matter in postmortem multiple sclerosis cortex. Neurochem Res. 2013;38(11):2385–96. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zeng M, Stamler JS. Hemoglobin induction in mouse macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(12):6643–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi H, Inagi R, Kato H, Tanemoto M, Kojima I, Son D, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Hemoglobin is expressed by mesangial cells and reduces oxidant stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(8):1500–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(13):938–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotti F, Lenaz G. Isolation and subfractionation of mitochondria from animal cells and tissue culture lines. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;80:3–44. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit A, Vadnal J, Houston S, Freeman E, McDonough J. Impaired regulation of electron transport chain subunit genes by nuclear respiratory factor 2 in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;279:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman MM, Straub AC. The emerging roles of somatic globins in cardiovascular redox biology and beyond. Redox Biol. 2013;1:405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. ImageJ, U. S. National institutes of health. Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997-2014. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- Reeder BJ. The redox activity of hemoglobins: from physiologic functions to pathologic mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13(7):1087–123. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2974. doi:10.1089/ars.2009.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter F, Meurers BH, Zhu C, Medvedeva VP, Chesselet M-F. Neurons express hemoglobin α- and β-chains in rat and human brains. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:538–547. doi: 10.1002/cne.22062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Hiltunen M, Kaarniranta K. Krebs cycle intermediates regulate DNA and histone methylation: epigenetic impact on the aging process. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelshorn DW, Schneider K, Weber AW, Kruger D, Dittgen C, Burgers HF, Sabouri F, Gassler N, Bach A, Martin H, Maurer MH. Expression of hemoglobin in rodent neurons. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:585–595. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard F, Greville-Heygate O, Marsh O, Anderson S, Chakrabarti L. A mitochondrial location for haemoglobins—dynamic distribution in ageing and Parkinson's disease. Mitochondrion. 2014;14(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.12.001. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal NK, Li S, Arning E, Alkhayer K, Clements R, Sarcyk Z, Dassanayake RS, Brasch NE, Freeman EJ, Bottiglieri T, McDonough J. Changes in methionine metabolism and his-tone H3 Trimethylation are linked to mitochondrial defects in multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2015;35(45):15170–15186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4349-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub AC, Lohman AW, Billaud M, Johnstone SR, Dwyer ST, Lee MY, Bortz PS, Best AK, Columbus L, Gaston B, Isakson BE. Endothelial cell expression of haemoglobin α regulates nitric oxide signalling. Nature. 2012;491(7424):473–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers MC, Kuiper C, Dachs GU. Regulation of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases and implications for cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(4):945–51. doi: 10.1042/BST20140118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG. Ions, energy and axonal injury: towards a molecular neurology of multiple sclerosis. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12(5):192–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte ME, Nijland PG, Drexhage JA, Gerritsen W, Geerts D, van Het Hof B, Reijerkerk A, de Vries HE, van der Valk P, van Horssen J. Reduced expression of PGC-1α partly underlies mitochondrial changes and correlates with neuronal loss in multiple sclerosis cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125(2):231–43. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]