Abstract

The recognition of functional roles for transcribed long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) has provided a new dimension to our understanding of cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis. LncRNAs are a large group of structurally complex RNA genes that can interact with DNA, RNA or protein molecules to modulate gene expression and to exert cellular effects through diverse mechanisms. The emerging knowledge regarding their functional roles and their aberrant expression in disease states emphasizes the potential for lncRNA to serve as targets for therapeutic intervention. In this concise review, we outline the mechanisms of action of lncRNAs, their functional cellular roles, and their involvement in disease. Using liver cancer as an example, we provide an overview of the emerging opportunities and potential approaches to target lncRNA dependent mechanisms for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: Long noncoding RNA, hepatocellular carcinoma, chemoresistance, epigenetics, therapeutics, gene regulation

1. Introduction

The availability and integrated use of advanced genome analysis platforms in recent years by consortia such as the Human Genome Project, Functional Annotation of the Mammalian genome project (FANTOM), and the Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) project, have revealed that only a very small proportion of the actively transcribed human genome corresponds to protein-coding genes (Dingemans et al., 2014; Fatemi, Velmeshev, & Faghihi, 2014; Z. Zhang et al., 2014). The recognition and identification of transcribed RNAs such as the microRNAs that do not encode for proteins but yet have specific biological functions have prompted a re-evaluation of the central dogma and emphasize a versatile role of RNA beyond that of a transitional role in translation of DNA to protein. The large numbers of pervasive non-coding RNA transcripts allows us to presume that many functionally active and biologically relevant non-coding RNA (ncRNA) remain to be identified. Considering their ubiquitous presence and diversity, these non-coding RNA could be major contributors to normal cellular physiological processes.

Classification of RNA genes

NcRNAs can be arbitrarily classified into two groups based on the length of their transcripts. Small RNAs, with less than 200 nucleotides, include several distinct types of RNAs such as microRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, PIWI-interacting RNAs and endogenous small interfering RNAs. Long RNAs, greater than 200 nucleotides include long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs), natural antisense transcripts (NATs), transcribed ultraconserved regions (T-UCRs), long enhancer ncRNAs, non-coding repeat sequences, and pseudogenes. In contrast to some types of small ncRNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs), the mechanism and functions of long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) are very poorly understood (Dingemans, et al., 2014; Kimura et al., 2015; Y. Yang et al., 2013).

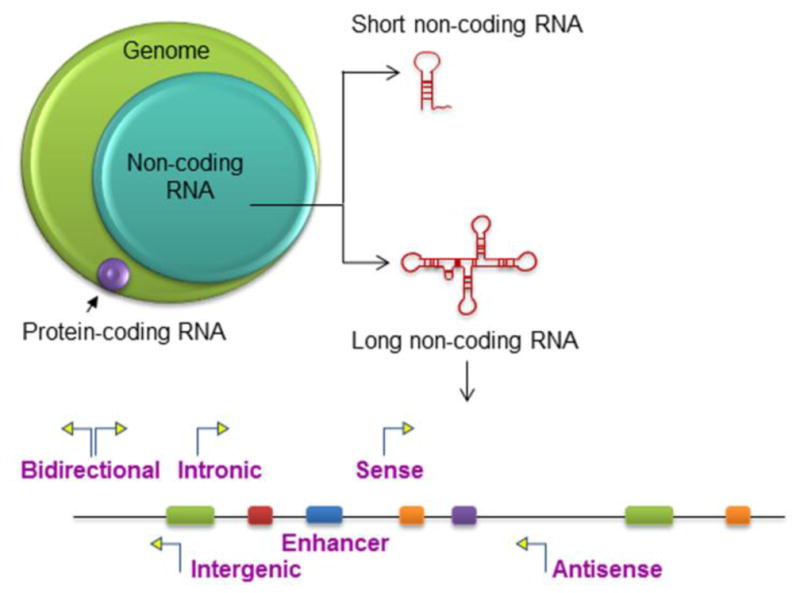

The lncRNAs are a highly abundant and heterogeneous group, in part reflecting their enormous diversity and structural complexity. Pointers to a functional biological role include the recognition of tissue-specific expression patterns, emerging literature showing functional relevance in complex physiological and pathological processes, and evidence of their involvement in several human diseases. In contrast to the protein coding genes, the number of lncRNAs has increased tremendously along the evolutionary process and reflects the complexity of the organism. (Necsulea et al., 2014). Despite this, an effective and useful method to categorize this large and heterogeneous group is lacking. A descriptive classification is based on genomic proximity to protein-coding genes. Depending on genomic location they can be divided broadly into several categories (Figure 1): 1. Intronic lncRNAs are located within an intron of a coding gene; 2. Intergenic lncRNAs (lincRNAs) are present between two protein-coding genes; 3. Bidirectional lncRNAs are expressed within the vicinity (within 1kb) of a coding transcript of the opposite strand; 4. Enhancer lncRNAs (e-lncRNAs) are present in the enhancer regions close to the promoter; 5. Sense: or 6. Antisense lncRNAs are those that overlap with one or more introns and exons of a different transcript on the same or opposite strand, respectively (Devaux et al., 2015; Hirose et al., 2014; H. Takahashi & Carninci, 2014). Non-coding repeats are another important class of lncRNAs that can have biological functions.

Figure 1. Non-coding RNA.

Non-coding RNA comprise a much larger portion of the human genome than protein-coding RNA, which comprise of <3% of the genome. Non-coding RNAs are arbitrarily classified into short and long non-coding RNA based on transcript size. LncRNA can be designated as Intergenic, Intronic, Enhancer, Sense, Antisense, or Bidirectional based on their genomic location relative to that of nearby protein-coding genes.

While a location-based classification may be useful for their recognition and annotation, an accurate classification of lncRNAs with respect to their biological role or biological activity is lacking.

Efforts to develop lncRNA databases have used systematic identification and annotation of lncRNAs within the human genome. The cDNA clone analysis within the FANTOM project led to the identification of over 23,000 lncRNAs (Carninci et al., 2005), while the GENCODE-ENCODE project identified approximately 24,000 lncRNA producing loci (Derrien et al., 2012). An analysis of a compendium of 7,256 RNA-seq libraries from tumors, normal tissues, and cell lines and comprehensively delineated genome-wide lncRNA expression reported the identification of 58,648 lncRNA genes (Iyer et al., 2015).

Mechanisms of action

As may be expected from their structural diversity, a wide range of functions have been described for lncRNAs. These include gene transcription, epigenomic regulation, translation of protein-coding genes, RNA turnover, chromatin organization, and genome defense (Ferraiuolo et al., 2010). Notably, most of the functions described to date involve regulation of gene expression, both of protein-coding genes or other non-coding RNAs, through a multitude of mechanisms as outlined in Table 1 and Figure 2. LncRNAs differ from small RNAs in both complexity and length. The structural complexity of lncRNAs offers multiple possibilities for interactions with DNA, RNA and/or proteins that depend on the secondary and tertiary structures. Likewise, the length of lncRNAs enables the formation of multi-component complexes such as those involved in epigenetic regulation of transcription. LncRNAs may be transcribed from DNA in several orientations, and can interact with genomic DNA elements, as well as with proteins in multiple configurations.

Table 1.

Long noncoding RNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms

| lncRNA | Function | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA transcription | |||

| HOTAIR | ↓ at the HOXD locus | Chromatin-mediated ↓ | (Tsai et al., 2010) |

| HOTTIP | ↑ at the HOXA locus | Chromatin-mediated ↑ | (K. C. Wang et al., 2011) |

| XIST | X inactivation | Chromatin-mediated ↓ | (Zhao, Sun, Erwin, Song, & Lee, 2008) |

| ANRIL | ↓ at the INK4b-ARF- INK4a locus | Chromatin-mediated ↓ | (Kotake, et al., 2011) |

| KCNQ1OT1 | Imprinting at the KCNQ1 cluster | Chromatin-mediated ↓ | (Pandey et al., 2008) |

| GAS5 | ↓ of glucocorticoid receptor- mediated transcription | DNA mimicry | (Kino, et al., 2010) |

| CCND1 promoter RNA | ↓ of CCND1 transcription | Allosteric ↑ of TLS | (X. Wang et al., 2008) |

| NRON | ↓ of NFAT-mediated transcription | ↓ of transcription factor nucleocytoplasmic shuttling | (Willingham et al., 2005) |

| AIRN | Imprinting at the IGF2R cluster | Chromatin-mediated ↓, transcription interference | (Latos et al., 2012) |

| IME4 antisense | ↓ of IME4 mRNA interference | Transcription | (Hongay, et al., 2006) |

| SRG1 | ↓ of SER3 mRNA | Nucleosome remodeling | (Hainer, Pruneski, Mitchell, Monteverde, & Martens, 2011) |

| ICR1 and PWR1 | ↓ and ↑ of FLO11mRNA, respectively | Modulation of transcription factor recruitment | (Bumgarner et al., 2012) |

| Alu repeat- containing RNA | Transcriptional ↓ during heat shock | ↓ of Pol II | (Mariner et al., 2008) |

| HSR1 | ↑ of HSF1 | Allosteric ↑ together with eEF1A | (Shamovsky, Ivannikov, Kandel, Gershon, & Nudler, 2006) |

| mRNA processing | |||

| MALAT-1 | Serine/Arginine splice factor modulation | Scaffolding nuclear domain | (Tripathi et al., 2010) |

| ZEB2 | ↑ of ZEB2 translation | Controlled splicing of IRES-containing intron region | (Beltran et al., 2008) |

| Neuroblastoma MYC | ↓ of neuroblastoma MYC intron 1 splicing | Controlled splicing via RNA-RNA duplex formation | (Krystal, Armstrong, & Battey, 1990) |

| Sas10mRNA 3′ UTR | ↓ of Rnp4F mRNA | RNA editing | (Peters, Rohrbach, Zalewski, Byrkett, & Vaughn, 2003) |

| Post-transcriptional modulation | |||

| HULC | ↓ of miRNA-mediate repression | Sequestration of miRNAs | (J. Wang, et al., 2010) |

| PTENP1 pseudogene | ↑ of PTEN | Sequestration of miRNAs | (Poliseno et al., 2010) |

| CDR1as | ↓ of miRNA-mediate repression | Sequestration of miRNAs | (Hansen et al., 2013) |

| BACE1AS | ↑ of BACE1 | Blocking miRNA- induced repression | (Faghihi et al., 2010) |

| Antisense UCHL1 | ↑ of UCHL1 protein level | Translational upregulation | (Carrieri et al., 2012) |

| Protein activity | |||

| EVF2 | Transcriptional ↑ of DLX2 targets | ↑ of DLX2 | (Feng et al., 2006) |

| 15q11-q13 sno- lncRNA | Alternative splicing | ↓ of FOX2 function | (Yin et al., 2012) |

| mcs-1 | Dicer-mediated ↓ | Sequestration of Dicer or other RNA-binding proteins | (Hellwig & Bass, 2008) |

| sfRNA | Stabilization of viral and host mRNAs | ↓ of XRN1- mediated mRNA degradation | (Moon et al., 2012) |

| gadd7 | ↓ of TDP43-mediated regulatory events | Sequestration of TDP43 | (X. Liu, Li, Zhang, Guo, & Zhan, 2012) |

| Protein complex organization | |||

| HOTAIR | ↓ at the HOXD locus | Recruitment of PRC2 and LSD1 | (Tsai, et al., 2010) |

| KCNQ1OT1 | Imprinting at the KCNQ1 cluster | Recruitment of PRC2 and G9A | (Pandey, et al., 2008) |

| ANRIL | ↓ at the INK4b-ARF- INK4a locus | Recruitment of PRC1 and PRC2 | (Kotake, et al., 2011; Yap et al., 2010) |

| TERC | Inclusion of telomeric repeats to chromosomal ends | Scaffolding for telomere components and template identification for repeat sequences | (Zappulla & Cech, 2004) |

| NEAT1 | Paraspeckles formation | Nucleation of subnuclear domains | (Sasaki, et al., 2009) |

| SRP RNA | Guiding proteins to ER | Scaffolding of SRP components | (Halic et al., 2004) |

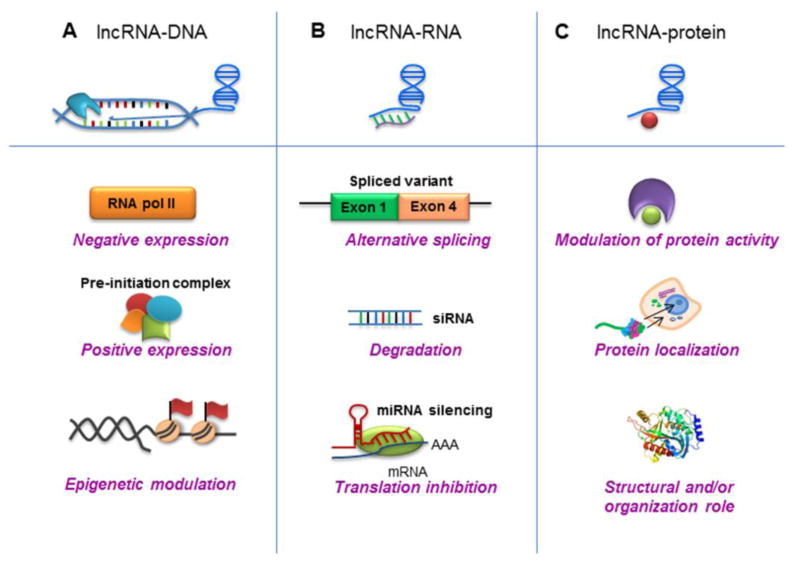

Figure 2. lncRNA interactions and actions.

(A) LncRNAs can target genomic DNA loci, and can modulate gene transcription by associating with RNA pol II or pre-initiation complexes, or through epigenetic modulation by guiding chromatin-modifying complexes to target genomic DNA loci. (B) LncRNA can contribute to RNA inhibition or degradation, by association with mRNAs and miRNAs to regulate splicing, or by acting as endogenous sponges. (C) LncRNAs can modulate protein activity and localization by acting as molecular guides and scaffolds or as decoys for proteins such as transcription factors.

While the majority of lncRNA are present within the cytoplasm, some lncRNAs are primarily confined within the nucleus (Z. Zhang, et al., 2014). Trans-acting nuclear lncRNAs can act in a tissue-specific manner in conjunction with chromatin modifiers such as histone modifying complexes and DNA methyltransferases, to epigenetically regulate or to modulate transcription (Tao et al., 2013). However, the mechanism by which these lncRNAs can recognize specific genomic loci is not well understood. It is hypothesized that interactions with genomic regions may be dictated by secondary or tertiary structural elements. Efforts to define and categorize RNA structural modules may enable systematic approaches to evaluate this hypothesis in the future. Some lncRNAs have been shown to maintain the nuclear architecture by scaffolding the assembly of DNA-RNA-protein interface at specific locations. In contrast, cis-acting lncRNAs may be able to regulate gene expression in a locus and allele-specific manner because of their genomic proximity to their targets. Cis-acting lncRNAs have been implicated in genomic imprinting, dosage compensation, and enhancer functions (Chen, Xu, & Liu, 2013; Xu et al., 2013). In such cases, modulation of neighboring gene expression can occur via direct binding or through the recruitment of chromatin-binding proteins that can modify the chromatin structure in the vicinity. While most of the well-studied lncRNAs regulate cellular activities at the nuclear level, others are localized within the cytosol and mediate post-transcriptional control via RNA-RNA interactions (Chapman et al., 2014). They can act as sponges and interact with short non-coding RNAs, such as miRNAs to simultaneously influence the expression of several thousands of miRNA-target genes leading to an overall change in cellular physiology.

The functional heterogeneity of lncRNAs is further emphasized by their ability to contribute to multi-protein complex formation, and participate in protein localization and function. In addition, a role for lncRNA as mediators of inter-cellular signaling is also being recognized by studies that have demonstrated the presence of lncRNA within extracellular vesicles, their release during conditions of cellular stress and their ability to modulate cellular responses in recipient cells after uptake of these vesicles (Kogure, Yan, Lin, & Patel, 2013; K. Takahashi, Yan, Haga, & Patel, 2014; K. Takahashi, Yan, Wood, Haga, & Patel, 2014).

2. LncRNA in human cancers

The ability of lncRNA to alter cellular physiology by altering gene expression raises the possibility that deregulated lncRNA expression may contribute to disease pathophysiology. Altered expression of lncRNA has been reported in many cancers and in other disease settings. Based on the emerging literature, lncRNA may be useful in elucidating disease pathogenesis and pathophysiology. In settings where alterations in lncRNA are associated with disease states, lncRNA may have roles as therapeutic targets or as biomarkers of disease (Table 2). Recent studies implicate the potential role of lncRNAs in cancer development by virtue of their ability to interact with DNA, RNA, proteins and/or their combinations, and their potential to modulate many of the hallmarks of cancer (Figure 3). A specific group characterized by non-coding repeats can activate immune responses and contribute to disease progression (Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Leonova et al., 2013; Rooney, Shukla, Wu, Getz, & Hacohen, 2015; Roulois et al., 2015; Tanne et al., 2015). Examples include LINE-1. HERV, Satellites, and TERRA. In addition, the LINE-1 repeat (CoT-1) may affect chromatin formation. These repeats are actively reverse transcribed and re-incorporate in the genome in cancers, thus causing an expansion of specific genomic regions (Bersani et al., 2015; Hall et al., 2014; Iskow et al., 2010; E. Lee et al., 2012; Rodic et al., 2015). TERRA plays a role in telomere extension through the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) pathway (Flynn et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Long noncoding RNA associated with human diseases

| Disease | Type of disease | lncRNA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | Myocardial infarction | MIAT | (Ishii et al., 2006) |

| Myocardial ischemia | HIF1A | (Zolk, Solbach, Eschenhagen, Weidemann, & Fromm, 2008) | |

| Diabetes | Transient neonatal diabetes mellitus | HYMAI | (Mackay et al., 2002) |

| PINK1-AS | (Scheele, Nielsen, et al., 2007) | ||

| Genetic disorders | X-fragile syndrome | FMR4 | (Khalil, Faghihi, Modarresi, Brothers, & Wahlestedt, 2008) |

| HELLP Syndrome | HELLPAR | (van Dijk et al., 2012) | |

| Silver-Russell, Beckwith- Wiedemann syndrome | KCNQ1OT1 | (Chiesa et al., 2012) | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Linc-MD1 | (Cesana et al., 2011) | |

| Facioscapulohu- meral muscular dystrophy | DBET | (Cabianca et al., 2012) | |

| Neurological disorders | Alzheimer’s disease | BACE1-AS, NAT- Rad18, 17A | (Faghihi et al., 2008) |

| Schizophrenia | DISC2, GOMAFU | (Chubb, Bradshaw, Soares, Porteous, & Millar, 2008) | |

| Huntington | TUNA | (N. Lin et al., 2014) | |

| Parkinson | naPINK1 | (Scheele, Petrovic, et al., 2007) | |

| Cancer | Female cancers (breast, ovary, uterine, cervical) | HOTAIR, H19, GAS5, ANRASSF1, UCA1, SRA, PVT1, CCAT2, MALAT-1, XIST | (L. Cui et al., 2013; Khalil, et al., 2008; Kino, et al., 2010; Mizrahi, et al., 2009; Z. Zhang, et al., 2014) |

| Colon | MALAT-1/NEAT2, PTENP1, HOTAIR, CCAT1, CCAT2, CRNDE, CUDR, H19, PVT1, KCNQ1OT1, ncRAN/SNHG16 | (L. D. Graham et al., 2011; M. Z. Ma et al., 2015; Michalik, et al., 2014; Nakano et al., 2006) | |

| Renal | CUDR, H19, UCA1, ncRAN/SNHG16, | (Fan, et al., 2014; Y. Wang et al., 2012) | |

| Liver | HULC, HOTAIR, TUC338, H19, MEG3, lncRNA-ATB, HEIH, PCNA-AS1, MALAT-1, HOTTIP, linc-RoR | (Anwar et al., 2012; Du et al., 2012; Geng, Xie, Li, Ma, & Wang, 2011; Ishibashi et al., 2013; K. Takahashi, Yan, Kogure, et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2014) | |

| Prostate | PCA3, ANRIL/p15AS, MALAT-1/NEAT2, PCAT-1, PCGEM1, PTENP1, CTBP1-AS, ANRASSF1, NEAT1, PlncRNA-1, PRNCR1, SRA, SChLAP1/PCAT 114 | (Chung et al., 2011; Z. Cui et al., 2013; Kotake, et al., 2011; G. L. Lee, et al., 2011; Petrovics et al., 2004; Prensner et al., 2011) | |

| Lung | MALAT-1/NEAT2, linc-p21, TUG1, CCAT2, CUDR, HOTAIR, PVT1, AK126698 | (Dingemans, et al., 2014; Gutschner, et al., 2013; Hou, et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2014; Y. Yang, et al., 2013) | |

| Leukemia | ANRIL/p15AS, uc.73a, MEG3, HOTTIP, XIST, PVT1, NEAT1 | (Folkersen et al., 2009; M. Graham & Adams, 1986; Rack et al., 1994; Zeng et al., 2014) | |

| Gastrointestinal | CCAT1, H19, HOTAIR, PVT1, MALAT-1 | (Ding et al., 2014; Fellig et al., 2005; J. H. Liu, Chen, Dang, Li, & Luo, 2014; C. Ma et al., 2014) |

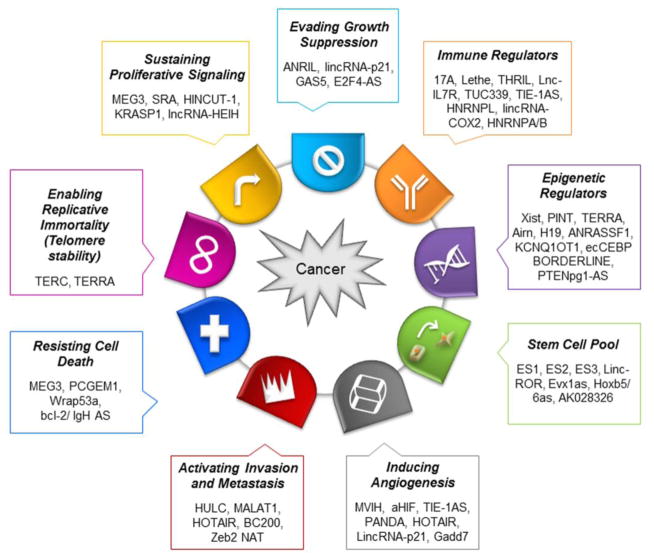

Figure 3. lncRNAs associated with hallmarks of cancer.

LncRNAs have been implicated in key hallmarks of cancer and can contribute to the onset and progression of cancer.

The emergence of comprehensive detection technology such as RNA-seq has enabled the cataloging of databases with information on several lncRNAs that are deregulated or aberrantly expressed in several types of cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), gastric cancer, renal cancer, colorectal cancer, glioma, prostate cancer, and others. High-throughput, comprehensive and multi-dimensional data analyses have extended our knowledge about molecular regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs that can control specific tumor-related behavior, thus adding a new stratum of key mediators and regulatory complexity during the evolution of cancer.

To highlight these, we will use liver cancers as an illustrative example. Liver cancers such as HCC are ideal to study lncRNA targets for treatment because liver uptake and delivery may be feasible for some therapeutic approaches. Several lncRNAs have been identified to play a functional role in HCC initiation and progression, as well as associated with recurrence, metastases or prognosis. These RNA genes could regulate epigenetic events in conjunction with chromatin modifying factors such as chromatin, histone-modifying enzymes, and DNA methylating agents leading to altered expression of target genes. The downstream cellular functions of these lncRNA transcripts are better understood than the mechanisms by which the expression of these lncRNAs are regulated, or their relevance to genetic or somatic mutations related to tumorigenesis. Examples of some functionally active lncRNAs that are associated with HCC are listed in Table 3. We emphasize these may represent just the tip of the iceberg, as many other lncRNA related to HCC or other cancers remain to be identified. To illustrate the diversity of functional mechanisms, we discuss a few of these herein (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Functional role of long noncoding RNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

| lncRNA | Classification | Genome Location | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | LincRNA | Chr6 | Promotes proliferation, positive correlation with histological grade or HBV | (Du, et al., 2012; J. Wang, et al., 2010; Xie, Ma, & Zhou, 2013) |

| HOTAIR | Antisense | Chr12 | Promotes metastasis, negative association with chemosensitivity and positively associated with invasion and recurrence | (Geng, et al., 2011; Ishibashi, et al., 2013; Z. Yang et al., 2011) |

| HOTTIP | Bidirectional | Chr7 | Promotes proliferation, Predictor of disease outcome and tumor progression | (Quagliata et al., 2014) |

| HEIH | LincRNA | Chr5 | Promotes proliferation by modulating cell cycle, associated with HBV-HCC | (F. Yang, et al., 2011) |

| H19 | LincRNA | Chr11 | Increased in HCC, suppresses metastasis via miR- 220 dependent pathway and associated with drug resistance | (Iizuka et al., 2002; Tsang & Kwok, 2007; L. Zhang et al., 2013) |

| LALR1 | Antisense | Chr17 | Promotes proliferation | (Xu, et al., 2013) |

| LET | Intronic | Chr15 | Suppresses metastasis | (F. Yang et al., 2013) |

| MALAT-1 | LincRNA | Chr11 | Promotes metastasis and recurrence, migration, invasion and synaptogenesis | (Lai, et al., 2012; R. Lin, et al., 2007) |

| MEG3 | LincRNA | Chr14 | Induces apoptosis, epigenetic modulator associated with methylation | (Anwar, et al., 2012; Braconi, Kogure, et al., 2011) |

| MVIH | Sense | Chr10 | Promotes angiogenesis, important predictor of recurrence-free survival | (Yuan et al., 2012) |

| RERT | Sense | Chr19 | Not understood | (Zhu et al., 2012) |

| uc002mb e.2 | LincRNA | Chr19 | Induce apoptosis | (L. Zhang, et al., 2013) |

| Linc-ROR | LincRNA | Chr18 | Tumor cell survival during hypoxia | (K. Takahashi, Yan, Haga, et al., 2014) |

| Dreh | Sense | Chr17 | Promotes metastasis | (J. F. Huang et al., 2013) |

| PCNA-AS1 | Antisense | Regulates proliferation and cell cycle | (Yuan, et al., 2014) | |

| UCA1/CUDR | Intronic | Chr19 | Chemotherapeutic resistance | (Tsang, Wong, Cheung, Co, & Kwok, 2007) |

| PVT1 | Variant | Chr8 | Regulates proliferation, cell cycle, and stem cell- like properties | (F. Wang, et al., 2014) |

| TUC338 | Ultra-conserved | Chr12 | Enhanced levels in liver cirrhosis and HCC, regulates cell growth | (Braconi, Valeri, et al., 2011) |

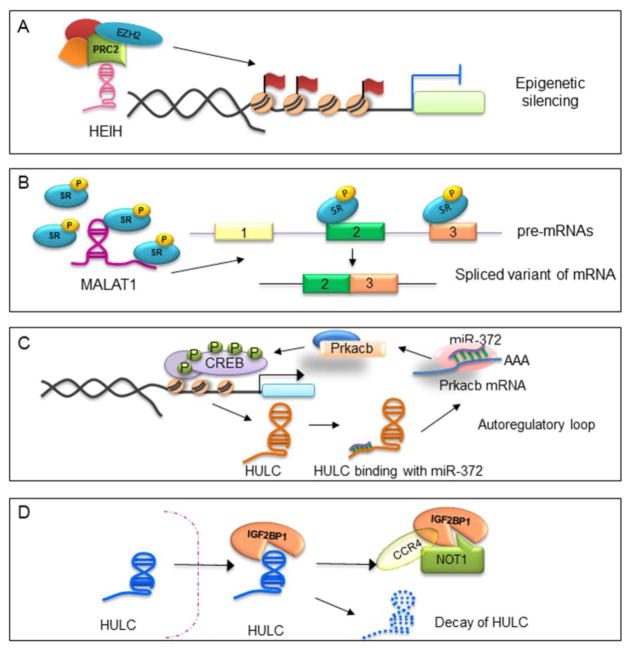

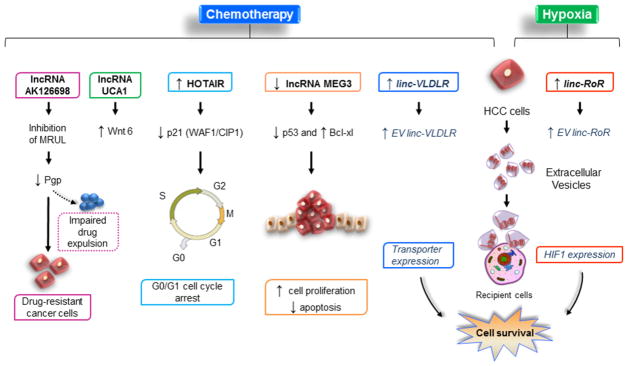

Figure 4. Examples of mechanisms of lncRNAs associated with liver cancers.

(A) Epigenetic silencing: lncRNA HEIH binds to EZH2 subunit of PRC2 complex, directing this complex to specific gene locus and regulate the expression of its target genes. (B) Splicing modulation: MALAT-1 transcript within the nuclear speckles modulates the activity of serine/arginine (SR) splicing factors to generate spliced variants. (C) lncRNA-miRNA interactions: lncRNA HULC acts as a molecular sponge to sequester miRNA-372 and de-repress PRKACB expression to enable phosphorylation and activation of CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein), thus stimulating HULC expression to activate an autoregulatory loop. (D) lncRNA-protein interactions: lncRNA HULC binds to oncofetal protein IGF2BP1 and guides it to its associating partner CCR4-NOT1 complex.

A classic example of lncRNA gene networking in HCC is Highly up-regulated lncRNA in liver cancer (HULC). Overexpression of HULC is associated with low-stage and low-grade tumors, implying a functional role in early stage of cancer progression. The cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) binds to a binding site in the promoter region of HULC, and this association leads to an autoregulatory loop of HULC with miR-372 via its conserved target site causing inhibition of translational repression of the catalytic subunit of PKA (PRKACB), a miR-372 target. This in turn increases the phosphorylation of CREB, making it more available to bind to proximal promoter of HULC. Overall, this autoregulatory loop leads to increased expression of HULC in HCC (J. Wang et al., 2010). HULC can also promote proliferation of HCC by targeting and suppressing p18. IGF2BP1, an oncofetal protein acts in trans to regulate HULC stability and expression by acting as a guide by bringing HULC into close proximity to the CCR4-NOT1 deadenylase complex (Hammerle et al., 2013). Metastasis associated in lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT-1) is another lncRNA that is upregulated in HCC; Although the mechanistic contribution of MALAT-1 to HCC is not known, MALAT-1 is associated with alternative splicing, and interacts with SF2/ASF and CC3 antigen to modulate SR proteins (serine/arginine-rich family of nuclear phosphoproteins) that regulate splicing of various pre-mRNAs (Lai et al., 2012; R. Lin, Maeda, Liu, Karin, & Edgington, 2007). LncRNA high expression in HCC (HEIH) can contribute to cell cycle arrest by association with enhancer of zeste homolog 2, a part of polycomb repressive complex 2 that leads to its recruitment to p16 promoter region, thereby preventing the expression of p16 gene (J. J. Huang et al., 2015; F. Yang et al., 2011). Non-coding repeat LINE-1 insertions occur with high frequency in HCC (Shukla et al., 2013) LncRNAs can also bind with miRNAs as sponges to regulate gene expression. These examples serve to illustrate the diversity of many unique lncRNA-based mechanisms in HCC.

The detection of certain lncRNAs in body fluids, like urine and plasma make them potential biomarkers of disease, similar to circulating miRNA. To explore the potential role of lncRNA as biomarkers, it will be necessary to establish the expression and stability of circulating lncRNAs in healthy and diseased states. For example, plasma levels of lncRNA HULC are higher in patients with HCC patients than in healthy controls. Similarly, PCA3, a prostate-specific lncRNA that is significantly overexpressed in prostate cancer may be a promising candidate for a diagnostic biomarker for prostate cancer (G. L. Lee, Dobi, & Srivastava, 2011). Establishing the relationship between circulating lncRNA and the disease course may yield prognostic markers, as suggested by a report of ncRNA MALAT-1, as an early prognostic indicator of poor survival rate in HCC.

Although the correlation between lncRNAs and human cancers is recognized, detailed mechanistic information regarding the contribution of lncRNA to these cancers is currently lacking. Nevertheless, the rapidly growing interest and emerging data are likely to provide many new mechanistic insights into the contributions of lncRNA in cancer, and thereby are expected to identify novel candidates for therapeutic intervention or biomarkers.

3. Therapeutic approaches to targeting lncRNA in cancers

Differential expression of lncRNA in tumors compared with normal tissues has been reported for many different cancers. The identification of lncRNA that are involved in cellular processes contributing to oncogenesis, tumor suppression, or tumorigenesis provides opportunities to develop novel therapeutics for cancer that are based on targeting lncRNA (Kimura, et al., 2015; Sasaki, Ideue, Sano, Mituyama, & Hirose, 2009). These genes differ from protein-coding RNA or miRNA in several ways that need to be considered in analyzing their effects or in exploring their therapeutic potential. First, their structural complexity and participation in multi-component complexes provides several potential targetable critical residues to modulate structure-based interactions. Second, they can subserve key regulatory roles in gene expression at absolute expression levels that are low in comparison with protein-coding genes. Third, they demonstrate tissue or cell-type specificity in expression. In addition, their effects can result from very diverse mechanisms of action, and they may also participate in inter-cellular communication. Finally, our current understanding of RNA gene function emphasizes the combinatorial nature of their action, which can result in complex interactions that incorporate multiple associated effectors. As a consequence, the functional impact of targeting lncRNA needs to be analyzed in a systemic context rather than as an individual target.

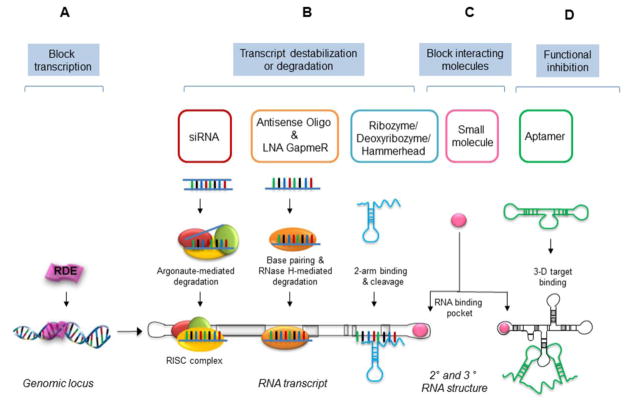

Several different types of approaches can be considered to target lncRNA and to modulate their expression for therapeutic purposes (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Strategies to target lncRNA.

(A) Gene transcription: DNA-binding elements can target the genomic locus to alter lncRNA transcription. (B) Transcript destabilization/degradation: siRNAs (19–30 nt long double-stranded RNAs) can bind to complementary lncRNA sequences through RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex). ASO and Gapmers (8–50 nt long single-stranded DNAs or RNAs can carry out sequence specific and RNase H-mediated lncRNA degradation. Ribozymes (single-stranded RNA in neutral condition) can undergo cellular processing to expose the hammerhead structure of the binding arms that bind with target sites and result in cleavage of the target lncRNA. (C) Block interactions. Small synthetic molecules can block binding of lncRNAs with protein, DNA, RNA or other interacting complexes by associating with specific binding pockets. (D) Functional disruption: Aptamers (3- dimensional short RNA or DNA oligonucleotides) can bind at specific structural regions to target lncRNA and antagonize their association with their binding partners.

Silencing of lncRNAs

Similar to other genes, lncRNA can be targeted by using specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that associate with RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex) complex and bind to specific target sequence based on complementarity leading to argonaute-mediated degradation of target sequence. For example, In a study by Hung et al, siRNA against promoter of CDKN1A antisense DNA damage activated RNA (PANDA) significantly reduced its expression and sensitized human fibroblasts to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis (Kimura, et al., 2015; Regha, Latos, & Spahn, 2006; F. Wang et al., 2014).

Natural antisense transcripts (NATs)

NATs are a type of lncRNA and their use illustrates an example of extending knowledge of lncRNA to design effective therapeutics. Inhibition of NATs can increase sense mRNA transcript levels (Modarresi et al., 2012) and the use of AntagoNATs is being evaluated as a therapeutic approach to upregulate the expression of specific sense mRNA (H. Takahashi & Carninci, 2014).

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)

Therapeutic strategies based on ASO could be used to target the expression and function of specific lncRNAs. ASOs are single stranded oligonucleotides that offer specific complementarity and RNase H-mediated degradation of target sequence. The feasibility of ASO-mediated knockdown to modulate MALAT-1 function has been demonstrated in lung cancer cells and murine xenografts where metastasis was restricted. ASO may be more effective than siRNAs for lncRNA targets in which the secondary structure of the lncRNA might preclude or limit optimal association with a siRNA. However, as with other ASO-targeting strategies, the adequacy of cellular uptake and potential for off-target effects needs to be considered (Gutschner et al., 2013; Kotake et al., 2011; Lebo, Niederer, & Zappulla, 2015; Zappulla & Cech, 2006).

Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) GapmeRs

The use of these provides an alternative to RNAi-knockdown of upregulated lncRNAs. These single-stranded oligonucleotide consist of a DNA stretch flanked by LNA nucleotides and, similar to ASOs, form base pairs with target lncRNA to induce degradation via RNAse H-dependent mechanism (Yang, Lu, & Yuan, 2014). Inhibition of MALAT-1 using GapmeRs resulted in a functional reduction in blood flow recovery and capillary density after hind limb ischemia (Michalik et al., 2014). However, this approach is currently limited only to nuclear localized oncogenic lncRNAs.

Ribozymes or deoxyribozmes

Catalytic degradation is another therapeutic strategy. These enzymes can target RNA and cleave in a site-specific manner via a protein-independent mechanism. ‘Hammerhead’-ribozymes are designed to have ~20 nt long arms flanking a central loop and these “arms” facilitate the binding with its targets. A significant inhibition of liver metastasis was observed by anti-VEGFR-1/2 ribozymes in preclinical studies in colon cancer model (Pavco et al., 2000). However, secondary structures of lncRNAs often disrupt efficient binding of these molecules to specific targets.

Aptamers

The use of single stranded oligonucleotide or peptide aptamers could overcome limitations imposed by structural features as they could bind by forming tertiary structures with their targets. Thus, they may provide a greater specificity than siRNAs, ASOs, or ribozymes. Moreover, the chemical structure of aptamers could be modified to enhance their stability and half-life. Aptamer-based -therapeutics are promising and undergoing clinical trials for many different indications such as non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and acute myeloid leukemia (Vitiello, Tuccoli, & Poliseno, 2015). In 2004, an anti-VEGF aptamer (Eyetech Pharmaceutics/ Pfizer) was approved by FDA for macular degeneration.

Small molecule inhibitors

As discussed above, lncRNAs exhibit dynamic binding affinities to various cellular components. Small molecules can mask the binding site for lncRNAs and prevent the association with its binding partners or antagonistic oligonucleotide sequences to disrupt interactions that are linked to altered function in disease-related lncRNA. For example, a small molecule inhibitor that prevents the binding of an oncogenic lncRNA, HOTAIR with its binding partners could restrict tumor cell invasion, angiogenesis, and metastatic potential (Tsai, Spitale, & Chang, 2011). Small molecules and oligonucleotides can also be used to interfere with the formation of RNA structures and disrupt folding patterns that modulate function.

RNA destabilizing elements (RDEs)

These can regulate lncRNA expression at the genomic level, and confer a knockout-like effect on gene function. RDEs have been successfully employed to reduce MALAT-1 expression (Miller et al., 2007).

Synthetic lncRNA mimics and other constructs

The use of synthetic mimics are being developed and tested for their ability to act as a decoy to block transcription of target genes or to restore their function. Alternatively, a plasmid BC-819 (DTA-H19) has been designed to specifically mediate its action through high abundance lncRNA H19 promoter to induce high levels of diphtheria toxin in tumors. The use of this construct has been shown to lead to an overall reduction in tumor size in human trials in several carcinomas although the underlying mechanisms need to be investigated (Mizrahi et al., 2009).

Several approaches to target lncRNA for therapeutic purposes can be considered once critical disease-relevant contributions of these genes have been identified. A major challenge of all of these approaches is to accomplish target-specific delivery. The use of synthetic nanoparticles for delivery of biologically active constructs has been extensively investigated. An alternative approach involves the use of extracellular vesicles, biologically derived particles that are involved in inter-cellular communication, and could be packaged with RNA genes for successful targeted therapy (Hongay, Grisafi, Galitski, & Fink, 2006; Kimura, et al., 2015). We have recently shown that lncRNAs within extracellular vesicles retain functional activity after they are taken up by recipient cells (K. Takahashi, Yan, Kogure, Haga, & Patel, 2014). The use of extracellular vesicles as delivery vehicles for lncRNA is thus highly attractive. Effective, target-specific therapy can be designed by fusing exosome membrane protein with specific peptides. Other potential advantages may include immune tolerance with the use of autologous vesicles, ability to traverse the blood-brain barrier and more effective tissue penetration into target tissues such as tumors.

Therapeutic resistance is a major challenge that limits the efficacy of cancer treatments. The role of lncRNAs in conferring differential drug-resistance phenotype is becoming appreciated, and several mechanisms for therapeutic resistance are now recognized. These include involvement of lncRNA in modulating survival signaling pathways, drug transporter expression and elimination, sensitization to apoptosis, DNA repair and cell cycle progression, and intercellular communication mediated by extracellular vesicles (Figure 6). A proposed mechanism involves trans-regulatory modulation of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) that regulates drug elimination in resistant cells. P-gp is in turn regulated by multi-drug resistance-related and upregulated lncRNA (MRUL) with inhibition of MRUL leading to increased chemotherapeutic drug-mediated apoptosis via reduction of P-gp expression and followed by impaired chemotherapeutic expulsion (Thiebaut et al., 1987; Y. Wang et al., 2014). Some lncRNAs have the ability to re-sensitize chemoresistant cancer cells to therapeutic agents like cisplatin by modulating DNA damage response pathways. Cisplatin-mediated upregulation of HOTAIR in human lung adenocarcinoma cells suppressed p21 (WAF1/CIP1) signaling pathway and caused a G0/G1 arrest by modulating the p53 expression (Z. Liu et al., 2013). Another lncRNA, urothelial cancer-associated 1 (UCA1) increased cisplatin-mediated resistance in human bladder cancer cells by regulating the Wnt signaling pathway. A proposed mechanism is upregulation of wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 6 (Wnt6), making this a potential target to overcome chemoresistance (Fan et al., 2014). Similarly, lncRNA AK126698 modulated cisplatin-resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells via Wnt pathway (Hou et al., 2014; Y. Yang, et al., 2013). We identified a novel lncRNA, lincRNA-ROR to be involved in mediating chemoresistance in human hepatocellular cells. Interestingly, this lncRNA was highly enriched within extracellular vesicles derived from HCC tumor cells and caused an increased lincRNA-ROR expression and reduced chemotherapy-induced cell death in recipient cells by modulating levels of TGFβ (tumor growth factor-beta) (K. Takahashi, Yan, Kogure, et al., 2014). LncRNA GAS5 renders glucocorticoid resistance by assuming a secondary structure that competes with the sequence within the response gene promoter region (Kino, Hurt, Ichijo, Nader, & Chrousos, 2010). PANDA contributes to anthracycline resistance in a subset of breast cancer cells by coordinating with NF-YA, a nuclear transcription factor that regulates apoptosis. Down regulation of PANDA led to increased chemotherapy sensitivity thus, suggesting a crucial role in drug resistance (Malek, Jagannathan, & Driscoll, 2014).

Figure 6. LncRNA-mediated mechanisms of therapeutic resistance.

Mechanisms of tumor cell resistance to chemotherapy or hypoxia involving lncRNA include modulation of drug transporters and elimination, survival signaling pathways, cell cycle progression and DNA repair, sensitization to apoptosis, and modulation of intercellular communication mediated by extracellular vesicles.

Although in vitro studies may provide promising results with regards to lncRNA function and their use as therapeutic targets, in vivo validation is extremely challenging and requires optimization at various levels. The poor conservation of lncRNA across species can confound the interpretation of data from animal studies. Our understanding of the mechanisms of action is rudimentary, and many intriguing questions remain unanswered such as the recruitment criteria for chromatin-remodeling complexes, whether or not the binding partners of lncRNAs are constant, or the impact of environment, localization, or associated disease states on lncRNA expression and function. The advent of genome engineering capabilities such as TALEN or CRISPR/Cas9 methodologies will enable the detailed study of lncRNA function (Hainer, Charsar, Cohen, & Martens, 2012; Hongay, et al., 2006). Definition of the repertoire of lncRNA in normal tissues or cells and in disease conditions will be necessary. There is a need to develop adequately sensitive detection techniques, and to comprehensively define structural and functional motifs and modules. Even with established targets for intervention, careful in vivo analyses will be necessary, followed by validation in appropriate patient cohorts. As the pace of research in lncRNAs progresses, addressing these challenges and gaps will provide opportunities for the development of novel therapeutic strategies based on targeting lncRNA for human cancers and other diseases.

4. Conclusions

Our current knowledge regarding lncRNA provides the basis and justification to further develop applications of lncRNA as disease markers and therapeutic targets. As discussed above, lncRNAs can interact with DNA, mRNA, ncRNAs and proteins to alter cellular physiology, can be deregulated in diseases such as cancer, and can form the basis for therapeutic intervention. Although a holistic and integrated approach that incorporates lncRNA with other proteins and genes will be necessary to successfully develop effective therapies, adding these RNA genes to our future armamentarium of therapeutics is likely to be very beneficial by providing new opportunities for intervention.

Table 4.

LncRNA-based therapeutic approach in cancer

| Agent | Description and Mechanism | Progress made |

|---|---|---|

| Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) | Double-stranded RNAs that associate with RISC complex and exhibit argonaute- mediated degradation depending on perfect sequence complementarity | Preclinical studies |

| Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) Example: LNA Gapmers | Single-stranded oligonucleotide sequence (13–25 nucleotides long) with perfect complementarity for target lncRNA. Effective binding with secondary structure of lncRNAs, RNase-H mediated degradation or blocking of the translational apparatus | Preclinical studies, Phase I and IIa |

| Ribozymes and deoxyribozymes (Hammerhead ribozymes) | A RNA (ribozyme) or DNA (deoxyribozyme) molecule that exhibits catalytic properties to cleave RNA in a site-specific manner. ~20 nucleotide long “arms” flanking a central loop target specific lncRNAs for cleavage | Preclinical studies |

| Aptamer | Single-stranded RNA or DNA oligonucleotides capable of efficiently targeting small molecules, peptides, proteins, RNA, lncRNA, and live cells by virtue of transforming to well-defined 3- dimensional shapes | Preclinical studies and early stage clinical trials |

| Small-molecule drugs | Chemical compounds that block the activity of target lncRNAs by structure-specific docking to regulate activity | Preclinical studies |

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grants DK069370 and UH3TR000884 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- HULC

highly upregulated in liver cancer

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- lncRNA

Long non-coding RNA

- lincRNA

Long intergenic non-coding RNA

- MALAT-1

metastasis associated in lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- mRNAs

messenger RNAs

- NATs

natural antisense transcript

- ncRNA

non-coding RNA

- siRNAs

small interfering RNAs

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anwar SL, Krech T, Hasemeier B, Schipper E, Schweitzer N, Vogel A, et al. Loss of imprinting and allelic switching at the DLK1-MEG3 locus in human hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran M, Puig I, Pena C, Garcia JM, Alvarez AB, Pena R, et al. A natural antisense transcript regulates Zeb2/Sip1 gene expression during Snail1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genes Dev. 2008;22(6):756–769. doi: 10.1101/gad.455708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersani F, Lee E, Kharchenko PV, Xu AW, Liu M, Xega K, et al. Pericentromeric satellite repeat expansions through RNA-derived DNA intermediates in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15148–15153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518008112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braconi C, Kogure T, Valeri N, Huang N, Nuovo G, Costinean S, et al. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30(47):4750–4756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braconi C, Valeri N, Kogure T, Gasparini P, Huang N, Nuovo GJ, et al. Expression and functional role of a transcribed noncoding RNA with an ultraconserved element in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(2):786–791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011098108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumgarner SL, Neuert G, Voight BF, Symbor-Nagrabska A, Grisafi P, van Oudenaarden A, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals that noncoding RNAs contribute to clonal heterogeneity by modulating transcription factor recruitment. Mol Cell. 2012;45(4):470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabianca DS, Casa V, Bodega B, Xynos A, Ginelli E, Tanaka Y, et al. A long ncRNA links copy number variation to a polycomb/trithorax epigenetic switch in FSHD muscular dystrophy. Cell. 2012;149(4):819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309(5740):1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri C, Cimatti L, Biagioli M, Beugnet A, Zucchelli S, Fedele S, et al. Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nature. 2012;491(7424):454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature11508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman EG, Costantino DA, Rabe JL, Moon SL, Wilusz J, Nix JC, et al. The structural basis of pathogenic subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) production. Science. 2014;344(6181):307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1250897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XG, Xu CS, Liu YM. Involvement of ERK1/2 signaling in proliferation of eight liver cell types during hepatic regeneration in rats. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12(1):665–677. doi: 10.4238/2013.March.11.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman B, et al. Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell. 2015;162(5):974–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa N, De Crescenzo A, Mishra K, Perone L, Carella M, Palumbo O, et al. The KCNQ1OT1 imprinting control region and non-coding RNA: new properties derived from the study of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Silver-Russell syndrome cases. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(1):10–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(1):36–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Nakagawa H, Uemura M, Piao L, Ashikawa K, Hosono N, et al. Association of a novel long non-coding RNA in 8q24 with prostate cancer susceptibility. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(1):245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Xie XY, Wang H, Chen XL, Liu SL, Hu LN. Expression of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR mRNA in ovarian cancer. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2013;44(1):57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Ren S, Lu J, Wang F, Xu W, Sun Y, et al. The prostate cancer-up-regulated long noncoding RNA PlncRNA-1 modulates apoptosis and proliferation through reciprocal regulation of androgen receptor. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(7):1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux Y, Zangrando J, Schroen B, Creemers EE, Pedrazzini T, Chang CP, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and ageing. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(7):415–425. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Li D, Gong M, Wang J, Huang X, Wu T, et al. Expression and clinical significance of the long non-coding RNA PVT1 in human gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1625–1630. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S68854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans AM, Bootsma G, van Baardwijk A, Reymen B, Wanders R, Brans B, et al. A phase I study of concurrent individualized, isotoxic accelerated radiotherapy and cisplatin-vinorelbine-cetuximab in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(5):710–716. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Kong G, You X, Zhang S, Zhang T, Gao Y, et al. Elevation of highly up-regulated in liver cancer (HULC) by hepatitis B virus X protein promotes hepatoma cell proliferation via down-regulating p18. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(31):26302–26311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, Wood DE, Sahagan BG, Morgan TE, et al. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14(7):723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi MA, Zhang M, Huang J, Modarresi F, Van der Brug MP, Nalls MA, et al. Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol. 2010;11(5):R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Shen B, Tan M, Mu X, Qin Y, Zhang F, et al. Long non-coding RNA UCA1 increases chemoresistance of bladder cancer cells by regulating Wnt signaling. FEBS J. 2014;281(7):1750–1758. doi: 10.1111/febs.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi RP, Velmeshev D, Faghihi MA. De-repressing LncRNA-Targeted Genes to Upregulate Gene Expression: Focus on Small Molecule Therapeutics. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e196. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellig Y, Ariel I, Ohana P, Schachter P, Sinelnikov I, Birman T, et al. H19 expression in hepatic metastases from a range of human carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(10):1064–1068. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bi C, Clark BS, Mady R, Shah P, Kohtz JD. The Evf-2 noncoding RNA is transcribed from the Dlx-5/6 ultraconserved region and functions as a Dlx-2 transcriptional coactivator. Genes Dev. 2006;20(11):1470–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraiuolo MA, Rousseau M, Miyamoto C, Shenker S, Wang XQ, Nadler M, et al. The three-dimensional architecture of Hox cluster silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(21):7472–7484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn RL, Centore RC, O’Sullivan RJ, Rai R, Tse A, Songyang Z, et al. TERRA and hnRNPA1 orchestrate an RPA-to-POT1 switch on telomeric single-stranded DNA. Nature. 2011;471(7339):532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature09772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkersen L, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Peden J, Malarstig A, Paulsson-Berne G, et al. Relationship between CAD risk genotype in the chromosome 9p21 locus and gene expression. Identification of eight new ANRIL splice variants. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng YJ, Xie SL, Li Q, Ma J, Wang GY. Large intervening non-coding RNA HOTAIR is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(6):2119–2128. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham LD, Pedersen SK, Brown GS, Ho T, Kassir Z, Moynihan AT, et al. Colorectal Neoplasia Differentially Expressed (CRNDE), a Novel Gene with Elevated Expression in Colorectal Adenomas and Adenocarcinomas. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(8):829–840. doi: 10.1177/1947601911431081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M, Adams JM. Chromosome 8 breakpoint far 3′ of the c-myc oncogene in a Burkitt’s lymphoma 2;8 variant translocation is equivalent to the murine pvt-1 locus. EMBO J. 1986;5(11):2845–2851. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, Hsu J, Kim Y, Hung G, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73(3):1180–1189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainer SJ, Charsar BA, Cohen SB, Martens JA. Identification of Mutant Versions of the Spt16 Histone Chaperone That Are Defective for Transcription-Coupled Nucleosome Occupancy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3 (Bethesda) 2012;2(5):555–567. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainer SJ, Pruneski JA, Mitchell RD, Monteverde RM, Martens JA. Intergenic transcription causes repression by directing nucleosome assembly. Genes Dev. 2011;25(1):29–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.1975011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halic M, Becker T, Pool MR, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Frank J, et al. Structure of the signal recognition particle interacting with the elongation-arrested ribosome. Nature. 2004;427(6977):808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LL, Carone DM, Gomez AV, Kolpa HJ, Byron M, Mehta N, et al. Stable C0T-1 repeat RNA is abundant and is associated with euchromatic interphase chromosomes. Cell. 2014;156(5):907–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerle M, Gutschner T, Uckelmann H, Ozgur S, Fiskin E, Gross M, et al. Posttranscriptional destabilization of the liver-specific long noncoding RNA HULC by the IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1703–1712. doi: 10.1002/hep.26537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495(7441):384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig S, Bass BL. A starvation-induced noncoding RNA modulates expression of Dicer-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(35):12897–12902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805118105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Virnicchi G, Tanigawa A, Naganuma T, Li R, Kimura H, et al. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(1):169–183. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongay CF, Grisafi PL, Galitski T, Fink GR. Antisense transcription controls cell fate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2006;127(4):735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Xu C, Xie H, Xu H, Zhan P, Yu L, et al. Long noncoding RNAs expression patterns associated with chemo response to cisplatin based chemotherapy in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JF, Guo YJ, Zhao CX, Yuan SX, Wang Y, Tang GN, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx)-related long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) down-regulated expression by HBx (Dreh) inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by targeting the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Hepatology. 2013;57(5):1882–1892. doi: 10.1002/hep.26195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JJ, Ma SX, Hou X, Wang Z, Zeng YD, Qin T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to AP (pemetrexed plus cisplatin) and gefitinib combination therapy in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34(2):94–98. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka N, Oka M, Yamada-Okabe H, Mori N, Tamesa T, Okada T, et al. Comparison of gene expression profiles between hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocellular carcinoma by oligonucleotide microarray data on the basis of a supervised learning method. Cancer Res. 2002;62(14):3939–3944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi M, Kogo R, Shibata K, Sawada G, Takahashi Y, Kurashige J, et al. Clinical significance of the expression of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(3):946–950. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Ozaki K, Sato H, Mizuno H, Saito S, Takahashi A, et al. Identification of a novel non-coding RNA, MIAT, that confers risk of myocardial infarction. J Hum Genet. 2006;51(12):1087–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskow RC, McCabe MT, Mills RE, Torene S, Pittard WS, Neuwald AF, et al. Natural mutagenesis of human genomes by endogenous retrotransposons. Cell. 2010;141(7):1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil AM, Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Brothers SP, Wahlestedt C. A novel RNA transcript with antiapoptotic function is silenced in fragile X syndrome. PLoS One. 2008;3(1):e1486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Aikata H, Takahashi S, Takahashi I, Nishibuchi I, Doi Y, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma ineligible for resection or ablation therapies. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(4):378–386. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Hurt DE, Ichijo T, Nader N, Chrousos GP. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvation-associated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci Signal. 2010;3(107):ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure T, Yan IK, Lin WL, Patel T. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Transfer of a Novel Long Noncoding RNA TUC339: A Mechanism of Intercellular Signaling in Human Hepatocellular Cancer. Genes Cancer. 2013;4(7–8):261–272. doi: 10.1177/1947601913499020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake Y, Nakagawa T, Kitagawa K, Suzuki S, Liu N, Kitagawa M, et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30(16):1956–1962. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal GW, Armstrong BC, Battey JF. N-myc mRNA forms an RNA-RNA duplex with endogenous antisense transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(8):4180–4191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MC, Yang Z, Zhou L, Zhu QQ, Xie HY, Zhang F, et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT-1 overexpression predicts tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Med Oncol. 2012;29(3):1810–1816. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latos PA, Pauler FM, Koerner MV, Senergin HB, Hudson QJ, Stocsits RR, et al. Airn transcriptional overlap, but not its lncRNA products, induces imprinted Igf2r silencing. Science. 2012;338(6113):1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1228110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebo KJ, Niederer RO, Zappulla DC. A second essential function of the Est1-binding arm of yeast telomerase RNA. RNA. 2015;21(5):862–876. doi: 10.1261/rna.049379.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Iskow R, Yang L, Gokcumen O, Haseley P, Luquette LJ, 3rd, et al. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science. 2012;337(6097):967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1222077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GL, Dobi A, Srivastava S. Prostate cancer: diagnostic performance of the PCA3 urine test. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8(3):123–124. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonova KI, Brodsky L, Lipchick B, Pal M, Novototskaya L, Chenchik AA, et al. p53 cooperates with DNA methylation and a suicidal interferon response to maintain epigenetic silencing of repeats and noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(1):E89–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216922110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Chang KY, Li Z, Gates K, Rana ZA, Dang J, et al. An evolutionarily conserved long noncoding RNA TUNA controls pluripotency and neural lineage commitment. Mol Cell. 2014;53(6):1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Maeda S, Liu C, Karin M, Edgington TS. A large noncoding RNA is a marker for murine hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26(6):851–858. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JH, Chen G, Dang YW, Li CJ, Luo DZ. Expression and prognostic significance of lncRNA MALAT1 in pancreatic cancer tissues. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(7):2971–2977. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.7.2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li D, Zhang W, Guo M, Zhan Q. Long non-coding RNA gadd7 interacts with TDP-43 and regulates Cdk6 mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2012;31(23):4415–4427. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Sun M, Lu K, Liu J, Zhang M, Wu W, et al. The long noncoding RNA HOTAIR contributes to cisplatin resistance of human lung adenocarcinoma cells via downregualtion of p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Nong K, Zhu H, Wang W, Huang X, Yuan Z, et al. H19 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by derepressing let-7’s suppression on its target HMGA2-mediated EMT. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(9):9163–9169. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma MZ, Chu BF, Zhang Y, Weng MZ, Qin YY, Gong W, et al. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes gallbladder cancer development via negative modulation of miRNA-218–5p. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1583. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay DJ, Coupe AM, Shield JP, Storr JN, Temple IK, Robinson DO. Relaxation of imprinted expression of ZAC and HYMAI in a patient with transient neonatal diabetes mellitus. Hum Genet. 2002;110(2):139–144. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek E, Jagannathan S, Driscoll JJ. Correlation of long non-coding RNA expression with metastasis, drug resistance and clinical outcome in cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(18):8027–8038. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA, Drullinger LF, Wagner SD, Kugel JF, et al. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol Cell. 2008;29(4):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik KM, You X, Manavski Y, Doddaballapur A, Zornig M, Braun T, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates endothelial cell function and vessel growth. Circ Res. 2014;114(9):1389–1397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Holmes MC, Wang J, Guschin DY, Lee YL, Rupniewski I, et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(7):778–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi A, Czerniak A, Levy T, Amiur S, Gallula J, Matouk I, et al. Development of targeted therapy for ovarian cancer mediated by a plasmid expressing diphtheria toxin under the control of H19 regulatory sequences. J Transl Med. 2009;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarresi F, Faghihi MA, Lopez-Toledano MA, Fatemi RP, Magistri M, Brothers SP, et al. Inhibition of natural antisense transcripts in vivo results in gene-specific transcriptional upregulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):453–459. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SL, Anderson JR, Kumagai Y, Wilusz CJ, Akira S, Khromykh AA, et al. A noncoding RNA produced by arthropod-borne flaviviruses inhibits the cellular exoribonuclease XRN1 and alters host mRNA stability. RNA. 2012;18(11):2029–2040. doi: 10.1261/rna.034330.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano S, Murakami K, Meguro M, Soejima H, Higashimoto K, Urano T, et al. Expression profile of LIT1/KCNQ1OT1 and epigenetic status at the KvDMR1 in colorectal cancers. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(11):1147–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necsulea A, Soumillon M, Warnefors M, Liechti A, Daish T, Zeller U, et al. The evolution of lncRNA repertoires and expression patterns in tetrapods. Nature. 2014;505(7485):635–640. doi: 10.1038/nature12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey RR, Mondal T, Mohammad F, Enroth S, Redrup L, Komorowski J, et al. Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol Cell. 2008;32(2):232–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavco PA, Bouhana KS, Gallegos AM, Agrawal A, Blanchard KS, Grimm SL, et al. Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of ribozymes targeting the messenger RNA of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):2094–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters NT, Rohrbach JA, Zalewski BA, Byrkett CM, Vaughn JC. RNA editing and regulation of Drosophila 4f-rnp expression by sas-10 antisense readthrough mRNA transcripts. RNA. 2003;9(6):698–710. doi: 10.1261/rna.2120703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovics G, Zhang W, Makarem M, Street JP, Connelly R, Sun L, et al. Elevated expression of PCGEM1, a prostate-specific gene with cell growth-promoting function, is associated with high-risk prostate cancer patients. Oncogene. 2004;23(2):605–611. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465(7301):1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, Dhanasekaran SM, Cao Q, Brenner JC, et al. Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):742–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M, Xu Y, Yang X, Wang J, Hu J, Xu L, et al. CCAT2 is a lung adenocarcinoma-specific long non-coding RNA and promotes invasion of non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(6):5375–5380. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1700-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quagliata L, Matter MS, Piscuoglio S, Arabi L, Ruiz C, Procino A, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTTIP/HOXA13 expression is associated with disease progression and predicts outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):911–923. doi: 10.1002/hep.26740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rack KA, Chelly J, Gibbons RJ, Rider S, Benjamin D, Lafreniere RG, et al. Absence of the XIST gene from late-replicating isodicentric X chromosomes in leukaemia. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(7):1053–1059. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regha K, Latos PA, Spahn L. The imprinted mouse Igf2r/Air cluster--a model maternal imprinting system. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113(1–4):165–177. doi: 10.1159/000090829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodic N, Steranka JP, Makohon-Moore A, Moyer A, Shen P, Sharma R, et al. Retrotransposon insertions in the clonal evolution of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):1060–1064. doi: 10.1038/nm.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, Shen SY, et al. DNA-Demethylating Agents Target Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inducing Viral Mimicry by Endogenous Transcripts. Cell. 2015;162(5):961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki YT, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T. MENepsilon/beta noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(8):2525–2530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele C, Nielsen AR, Walden TB, Sewell DA, Fischer CP, Brogan RJ, et al. Altered regulation of the PINK1 locus: a link between type 2 diabetes and neurodegeneration? FASEB J. 2007;21(13):3653–3665. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8520com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele C, Petrovic N, Faghihi MA, Lassmann T, Fredriksson K, Rooyackers O, et al. The human PINK1 locus is regulated in vivo by a non-coding natural antisense RNA during modulation of mitochondrial function. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamovsky I, Ivannikov M, Kandel ES, Gershon D, Nudler E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature. 2006;440(7083):556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature04518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla R, Upton KR, Munoz-Lopez M, Gerhardt DJ, Fisher ME, Nguyen T, et al. Endogenous retrotransposition activates oncogenic pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2013;153(1):101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Carninci P. Widespread genome transcription: new possibilities for RNA therapies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452(2):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yan IK, Haga H, Patel T. Modulation of hypoxia-signaling pathways by extracellular linc-RoR. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 7):1585–1594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.141069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yan IK, Kogure T, Haga H, Patel T. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of long non-coding RNA ROR modulates chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular cancer. FEBS Open Bio. 2014;4:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yan IK, Wood J, Haga H, Patel T. Involvement of extracellular vesicle long noncoding RNA (linc-VLDLR) in tumor cell responses to chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(10):1377–1387. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne A, Muniz LR, Puzio-Kuter A, Leonova KI, Gudkov AV, Ting DT, et al. Distinguishing the immunostimulatory properties of noncoding RNAs expressed in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15154–15159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517584112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao GZ, Lehwald N, Jang KY, Baek J, Xu B, Omary MB, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling protects mouse liver against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis through the inhibition of forkhead transcription factor FoxO3. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17214–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaut F, Tsuruo T, Hamada H, Gottesman MM, Pastan I, Willingham MC. Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(21):7735–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan Q, Watt AT, et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2010;39(6):925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329(5992):689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MC, Spitale RC, Chang HY. Long intergenic noncoding RNAs: new links in cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71(1):3–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang WP, Kwok TT. Riboregulator H19 induction of MDR1-associated drug resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(33):4877–4881. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang WP, Wong TW, Cheung AH, Co CN, Kwok TT. Induction of drug resistance and transformation in human cancer cells by the noncoding RNA CUDR. RNA. 2007;13(6):890–898. doi: 10.1261/rna.359007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk M, Thulluru HK, Mulders J, Michel OJ, Poutsma A, Windhorst S, et al. HELLP babies link a novel lincRNA to the trophoblast cell cycle. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):4003–4011. doi: 10.1172/JCI65171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello M, Tuccoli A, Poliseno L. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer: implications for personalized therapy. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2015;38(1):17–28. doi: 10.1007/s13402-014-0180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Yuan JH, Wang SB, Yang F, Yuan SX, Ye C, et al. Oncofetal long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes proliferation and stem cell-like property of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by stabilizing NOP2. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1278–1290. doi: 10.1002/hep.27239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu X, Wu H, Ni P, Gu Z, Qiao Y, et al. CREB up-regulates long non-coding RNA, HULC expression through interaction with microRNA-372 in liver cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):5366–5383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472(7341):120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Arai S, Song X, Reichart D, Du K, Pascual G, et al. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454(7200):126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen W, Yang C, Wu W, Wu S, Qin X, et al. Long non-coding RNA UCA1a(CUDR) promotes proliferation and tumorigenesis of bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(1):276–284. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang D, Wu K, Zhao Q, Nie Y, Fan D. Long noncoding RNA MRUL promotes ABCB1 expression in multidrug-resistant gastric cancer cell sublines. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(17):3182–3193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01580-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham AT, Orth AP, Batalov S, Peters EC, Wen BG, Aza-Blanc P, et al. A strategy for probing the function of noncoding RNAs finds a repressor of NFAT. Science. 2005;309(5740):1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1115901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Ma H, Zhou D. Plasma HULC as a promising novel biomarker for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:136106. doi: 10.1155/2013/136106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Yang F, Yuan JH, Zhang L, Bi HS, Zhou CC, et al. Long noncoding RNAs associated with liver regeneration 1 accelerates hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):739–751. doi: 10.1002/hep.26361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Huo XS, Yuan SX, Zhang L, Zhou WP, Wang F, et al. Repression of the long noncoding RNA-LET by histone deacetylase 3 contributes to hypoxia-mediated metastasis. Mol Cell. 2013;49(6):1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Zhang L, Huo XS, Yuan JH, Xu D, Yuan SX, et al. Long noncoding RNA high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates tumor growth through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in humans. Hepatology. 2011;54(5):1679–1689. doi: 10.1002/hep.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. LncRNA: a link between RNA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839(11):1097–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]