Abstract

The Olig2 basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor promotes oligodendrocyte specification in early neural progenitor cells (NPCs), including radial glial cells, in part by recruiting SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes to the enhancers of genes involved in oligodendrocyte differentiation. How Olig2 expression is regulated during oligodendrogliogenesis is not clear. Here, we find that the Brg1 subunit of SWI/SNF complexes interacts with a proximal Olig2 promoter and represses Olig2 transcription in the mouse cortex at E14, when oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPCs) are not yet found in this location. Brg1 does not interact with the Olig2 promoter in the E14 ganglionic eminence, where NPCs differentiate into Olig2-positive OPCs. Consistent with these findings, Brg1-null NPCs demonstrate precocious expression of Olig2 in the cortex. However, these cells fail to differentiate into OPCs. We further find that Brg1 is necessary for neuroepithelial-to-radial glial cell transition, but not neuronal differentiation despite a reduction in expression of the pro-neural transcription factor Pax6. Collectively, these and earlier findings support a model whereby Brg1 promotes neurogenic radial glial progenitor cell specification but is dispensable for neuronal differentiation. Concurrently, Brg1 represses Olig2 expression and the specification of OPCs, but is required for OPC differentiation and oligodendrocyte maturation.

Keywords: Brg1, oligodendrocyte progenitors, radial glia, Olig2, Pax6

Introduction

Oligodendrocytes are glial cells in the central nervous system (CNS) that generate myelin, a proteolipid that insulates axons and dramatically increases axonal conduction velocities through saltatory conduction. During development, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) arise from neuroepithelial stem/progenitor cells (NPCs) in three waves (Ivanova et al., 2003; Chojnacki and Weiss, 2004; Kessaris et al., 2006). The first OPCs originate in the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) and anterior entopeduncular area (AEP) in the ventral forebrain and populate the developing telencephalon including the cerebral cortex. A second wave of OPCs arises from the lateral and caudal ganglionic eminences (LGE and CGE) during perinatal development followed by a third wave in the postnatal cortex. Only subpopulations of these progenitors differentiate into mature, myelin-forming oligodendrocytes, with the embryonic MGE- and AEP-derived populations eliminated either just before or after birth (Kessaris et al., 2006).

The specification, differentiation and maturation of OPCs are controlled by distinct transcription factors that regulate the expression of oligodendrocyte lineage genes (reviewed by Emery and Lu, 2015). One such signal is the Olig2 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, which is expressed by all OPCs and is required for oligodendrocyte differentiation. Olig2 promotes the differentiation of NPCs into OPCs by regulating the expression of a number of transcription factors, including Sox10, Nkx2.2, Hes5 and others (Emery and Lu, 2015). Later, Olig2 is required for the maturation of OPCs into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes through the regulation of factors that activate myelin-associated genes. The activation of these transcription factors appears to depend on the activities of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factors. Mammalian SWI/SNF protein complexes regulate gene activation by altering chromatin structure in an ATP-dependent manner (reviewed by Lu and Roberts, 2013). Either Brahma (Brm) or Brahma-Related Gene-1 (Brg1) are present in SWI/SNF complexes and function as ATPases. Brg1 and other SWI/SNF proteins have been implicated in cell cycle regulation and differentiation in a number of cell types.

We previously found that conditional disruption of Brg1 in embryonic mouse NPCs leads to the failure of astrocyte and oligodendrocyte differentiation with relatively normal differentiation of at least early cortical and spinal cord neuronal populations (Matsumoto et al., 2006). Subsequently, Brg1 was reported to regulate OPC differentiation through a mechanism whereby Olig2 recruits Brg1 to oligodendrocyte-specific enhancers, thus regulating the transcription of genes involved in OPC maturation, including myelin genes (Yu et al., 2013). Brg1 also interacts with the pro-neurogenic transcription factor Pax6, which inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation (Ninkovic et al., 2013), raising the possibility that Brg1 may play dual roles in regulating the differentiation of NPCs into neurons and OPCs.

In contrast to studies suggesting that Brg1 is required for oligodendrocyte differentiation, Bischof and co-workers (2015) recently reported that Brg1 only plays a role in regulating the number of myelinating oligodendrocytes that arise during development. This study focused on mice with conditional loss of Brg1 in committed OPCs and late progenitor cell populations. It is possible, therefore, that Brg1 plays distinct roles during OPC specification, differentiation, and maturation. Here, we find that Brg1 interacts with a specific region of the Olig2 promoter and represses Olig2 transcription in progenitor cells in the developing cortex but not in the ganglionic eminences when OPCs arise in the ganglionic eminences but not in the cortex. Conditional loss of Brg1 in NPCs results in the generation of ectopic Olig2-positive cells in the cortex that are incapable of either oligodendrocyte or neuronal differentiation. We also find that Brg1 is required for the transition of neuroepithelial progenitor cells into radial glial, but not for the generation of early neurons derived from non-radial glial and radial glial cell progenitors. Brg1 therefore has distinct region and cell-type specific activities in the developing CNS.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were housed and bred in an environmentally controlled room at 23±2 °C, with a relative humidity of 50–60% and under a 12-h light: 12-h dark cycle. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Oregon Health & Science University. Male nestin-cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were mated with female Brg1FL/FL mice between 3 and 5 months of age as previously described (Matsumoto et al., 2006). Animals were genotyped as previously described (Sumi-Ichinose et al., 1997).

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were harvested at different developmental stages as indicated in the text below and CNS tissues were dissected and immersion-fixed at 4°C overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were then extensively washed in PBS and equilibrated in 30% sucrose as previously described (Matsumoto et al., 2006). The tissue was embedded in freezing medium (TBS, Triangle Biomed. Sci.) and sectioned at 20 µm on a cryostat (Hacker Inst). Sections were labeled with primary antibodies and detected with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies as previously described (Matsumoto et al., 2006). Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: rabbit-anti-BLBP, rabbit-anti-HuD, mouse-anti-Olig1, rabbit-anti-Olig1, rabbit-anti-Olig2, rabbit-anti-Tbr1, rabbit-anti-Tbr2, rabbit-anti-Map2, mouse-anti-Map2, mouse-anti-nestin, mouse-anti-GalC and guinea pig-anti-GLAST from Chemicon; mouse-anti-BrdU from Calbiochem; rabbit-anti-GalC , mouse-anti-Olig2 and rabbit-anti-Pax6 from Millipore; mouse-anti-cleaved-caspase-3 from Cell Signaling; mouse-anti-Pax6 and rat-anti-nestin (RC2) from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; and rat-anti-PDGFRα from BD PharMingen. Sections were counterstained with diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) from Molecular Probes. TUNEL assays were performed using a DNA Fragmentation Assay kit (Clontech). Cell counts were quantified and analyzed as previously described (Preston et al., 2013).

Cell culture

For chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, cerebral cortices and ganglionic eminences were dissected from Brg1FL/FL E14.5 mouse embryos. Tissues were dissociated as previously described (Matsumoto et al 2006). Cells were grown for 20 hours in a non-differentiating medium consisting of DMEM/F12 (1:1; Gibco) supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), B27 supplement (without vitamin A) and N2 (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Upstate Biotech), 20 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), and penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco).

For studies of oligodendrocyte differentiation, E13.5-E14.5 control and NC-Brg1FL/FL cortices were dissociated and expanded as neurospheres for one week as previously described (Zhang et al., 1998), then cells were allowed to adhere on uncoated polystyrene plates and were challenged with an oligodendrocyte-differentiation medium comprised of DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 0.1% BSA, platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGF-AA) and FGF2 at 20 ng/ml each, B27 supplement minus vitamin A , N1 supplement (Sigma) and D-Biotin 10 nM, (Sigma) as previously described (Preston et al, 2013).

The SW13 adrenal adenocarcinoma cell line was grown and transfected as previously described (Banine et al., 2005).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

After 20 hours, formaldehyde was added to neural stem cell culture medium at 1% final concentration and cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were collected and washed three times with ice-cold PBS containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were lysed and chromatin was sheared to generate fragments of different sizes (depending on the fragments targeted in the assay) as previously described (Banine et al., 2005; 2011). ChIP assays were performed as previousely described (Banine et al, 2011). For pre-clearing and pull downs, we used Protein A Sepharose (GE Healthcare) pre-blocked with yeast tRNA and BSA. The antibodies used were: rabbit anti-Pax6 (Millipore), rabbit anti-Brg1 and rabbit IgG (Santa-Cruz). PCRs were performed using Phusion hot start II High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher) and primers listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used for ChiP Assays

| Olig2 | −352F1:5’GAAAGTTGCAGGCGTTCCCT | +98R1:5’TTAGATTTGAGGTGCTCGCT |

|---|---|---|

| Olig2 | −842F2: 5’GAATGAGGTGGAAGTCGTTA | −335R2:5’GGAACGCCTGCAACTTTCA |

| Olig2 | −1340F4: 5’CTGGAAATGTCCGGATGTGA | −796R4:5’CAGTCAAAAGCGCCAACGCAT |

| Olig2 | −381F:5’CCTGACGCTACAGTGACAATA | −266R:5’AAAGGGCGAGCTGAAGAA |

| Olig2 | −283F:5’TTCTTCAGCTCGCCCTTTC | −185R:5’CTCTCAGCACACAGCCAAT |

| Olig2 | −239F:5’CATCCCTCCTCGCGGAATCTC | −129R:5’TGATGTCACCCGGCTAATTC |

| Olig2 | −163F:5’GGGTTTCATTGAGCGGAATTAG | −55R:5’GGGCGGGAACAATGTGCTTT |

| Olig2 | −75F:AAAAGCACATTGTTCCCGCC | +35R:5’GTAATAAGCATCCACACCTTTC |

| Olig2 | −22F:5’TGCCTCCACCCAGCTATAA | +98R1:5’TTAGATTTGAGGTGCTCGCT |

| Olig1 | −271F:5’TTTAGCCTGACCAGCTGAAC | −23R: 5’ACACCTTTAAACCCGGCTTG |

| P0Pax6 | −833F: 5’AGACCACGGGATCAGTATCT | −467R:5’GACCCAATGGATAACCCTACCT |

| P1Pax6 | −361F:5’GACCTCGTAGAGATGGTGAAAC | +80R:5’CTGAACCAGAGCGGGAAAT |

| P1Pax6 | −2737F: 5’CTTCGCCAGCCTTTCTATTCTA | −2277R:5’ACTGTTGGAAACTGCACAAAC |

| Pα Pax6 | −259F:5’GCAGTTCATTCTCGTCTGAGT | +110R:5’GTCTCCTCTCTTCTCCTCTCTT |

Olig2 promoter luciferase assays

PCR reactions of mouse genomic DNA were performed with +98R1 and −842F2 primers (see Table 1) to amplify a 940 bp fragment of the Olig2 promoter. The fragment was first subcloned in pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. The clone was digested with NcoI enzyme, treated with Klenow polymerase and dNTPs then digested with SalI enzyme. After purification, the fragment was ligated to blunted MluI and XhoI sites of the pGL2 basic vector (Promega). To generate additional Olig2 promoter constructs, pGl2 −842/+98 Olig2 luciferase was digested with NheI and SmaI to generate a pGl2 −296/+98 Olig2 luciferase construct. The pGl2 −842/+98 Olig2 luciferase construct was also digested with NarI enzyme followed by Klenow with dNTPs then HindIII. The 191bp fragment was then purified and subcloned into pGl2 HindIII and blunted MluI sites to generate a pGl2 −93/+98 Olig2 luciferase construct.

One microgram of each luciferase construct was co-transfected with 500ng of CMV β galactosidase reporter plasmid and 1µg or 500ng of Brg1 expression vector or pcDNA3 in SW13 cells using lipofectamine LTX (life Technologies). In each experiment, we tested the luciferase constructs in triplicate and at least 3 experiments were performed as previously described (Banine et al., 2005).

Statistics

For cell counts and counts of labeled cells in tissues, data were expressed as means ± standard deviations and data were analyzed using a Student’s t test with a p<0.01 considered significant for comparisons between groups.

Results

Disruption of Brg1 in early neural progenitors leads to ectopic Olig2 expression in the cerebral cortex

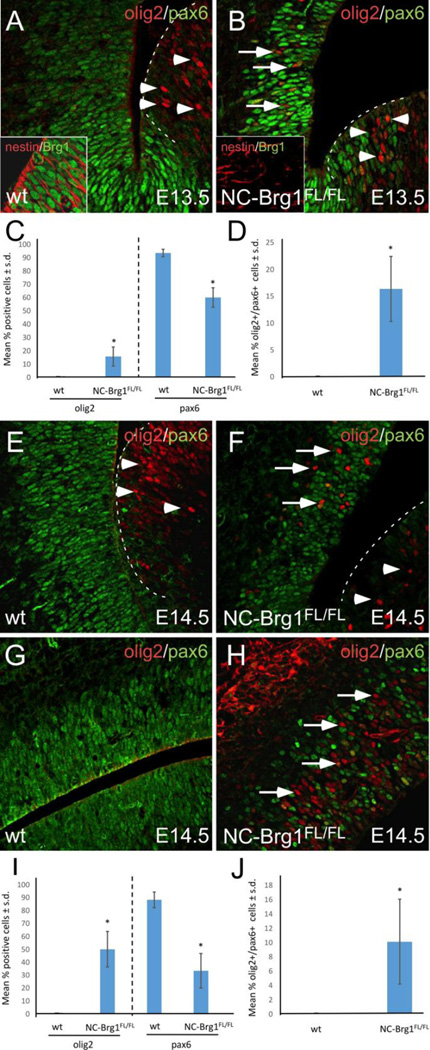

Brg1 is ubiquitously expressed in early stage mouse embryos, but its expression becomes enriched in neural tissue during embryogenesis (Randazzo et al., 1994) including by all cells in the cortical SVZ (Fig. 1A, inset) and in the ganglionic eminences (data not shown). We previously reported the virtual absence of OPCs (e.g. cells expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PDGF-Rα) throughout embryonic development in the CNS of mice with nestin-dependent disruption of Brg1 (NC-Brg1FL/FL mice ; Matsumoto, et al, 2006), which results in the complete absence of Brg1 expression in the developing brain (e.g. Fig. 1B, inset). To test the role of Brg1 in OPC specification, we examined the expression of Olig2 in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice. During early development, Olig2 is expressed by a large number of progenitor cells in the ventrally-derived ganglionic eminences but not in the cortical subventricular zone (SVZ) (Ivanova et al., 2003). In NC-Brg1FL/FL mice, we observed many Olig2+ cells in ventrally-derived ganglionic eminences at E13.5 in a pattern that was similar to that seen in wild type (wt) animals (compare Fig. 1 A, B, arrowheads). This pattern persisted at later times in development (data not shown). While no Olig2-immunoreactivity was observed in the cortical subventricular zone (SVZ) of wt animals, a large number of Olig2+ cells was observed in the cortical SVZ of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice as early as E13.5 (compare Fig. 1A and 1B, arrows; quantified in Fig. 1C). A small proportion of these ectopic Olig2+ cells also expressed Pax6 (Fig. 1D). This aberrant Olig2 expression increases throughout the cortex in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice by E14.5 (Fig. 1E–H; quantified in Fig. 1I) with the percentage of Olig2+/Pax6+ cells remaining the same (Fig. 1D, 1J). Thus, in the absence of Brg1, although NPCs fail to differentiate into OPCs, Olig2 expression is relatively normal in the ganglionic eminences and is ectopic in the cortical SVZ with some cells co-expressing Pax6.

Fig. 1.

Olig2 (red) and Pax6 (green) immunoreactivity in the cortex and ganglionic eminence at E13.5 (A, B) and E14.5 (E-H). Quantification of cortical staining is shown in C (for E 13.5) and I (for E.14.5), and quantification of cortical Olig2/Pax6 co-labeling is shown in D (for E13.5) and J (for E14.5). Control (wt) is shown in (A,E, G), NC-Brg1FL/FL (B,D,F). The insets in A and B show Brg1 (green) and nestin (red) staining in sections through E13.5 wt (A) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (B) cortical SVZ. The border between the ganglionic eminence and the cortex is indicated by dashed lines (A, B, E and F). The border between the ganglionic eminence and the cortex is shown in A, B, E and F while dorso-lateral cortex is shown in G and H. Note that the cortical plate of the control is not shown (G), while the entire width of the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex is in the image (H) due to the reduced size of the entire brain. In addition, the mediolateral cortex of the control is shown. Intense red label on the superficial aspect of the NC-Brg1FL/FL in panel (H) is an artifact of the developing cranial vault. Arrows in B, F, and H indicate ectopic Olig2 expression; arrowheads indicate Olig2 expression in the ganglionic eminence.

Although some of the ectopic Olig2+ cells express Pax6 in NC-Brg1FL/FL embryos, there is a marked reduction in Pax6 expression in the CNS of these animals. The vast majority of dorsal cortical progenitor cells in wt embryos express Pax6 (Fig. 1A, C, E, G, I). In NC-Brg1FL/FL cortices, however, Pax6 expression is profoundly reduced (Fig. 1B, C, F, H, I). At E14.5, for example, when the ectopic cortical Olig2 expression is highest, Pax6 expression is very sparse compared to wt animals (compare Figs. 1E and G with Figs. 1 F, H, and see Fig. 1I). This suggests that the Olig2+ cells may be generated at the expense of Pax6+ progenitors.

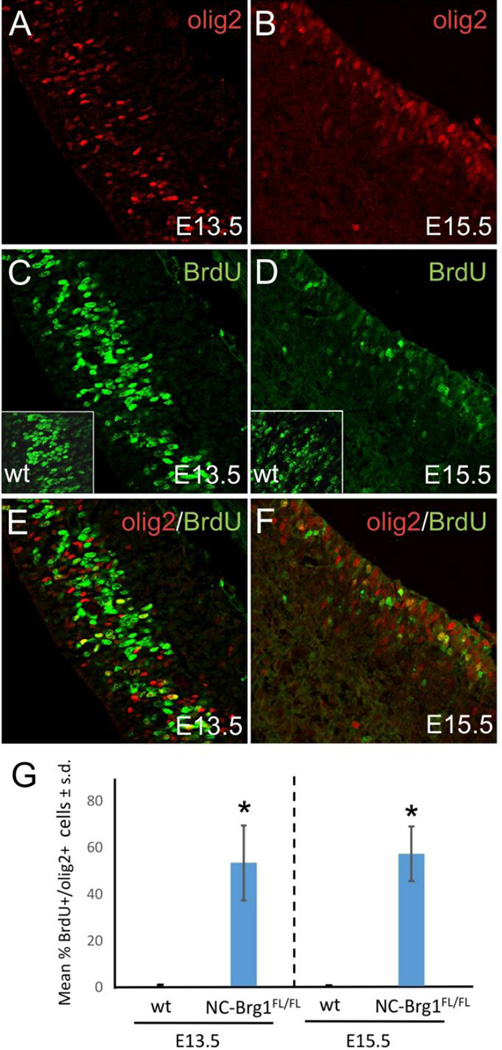

We used several strategies to clarify the origin of the precocious Olig2+ cells in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice. First, we labeled dividing cells with a one-hour pulse of BrdU at E13.5 (Fig. 2A, C, E, G) or E15.5 (Fig. 2B, D, F, G). We found that many of the Olig2+ cells in the cortical SVZ of Brg1FL/FL mice at both stages were BrdU+, indicating that dividing Olig2+ progenitors are being generated from cells located in the dorsal cortex, well before the normal migration of ventral Olig2+ progenitors in wt animals. Although there were many cells in wt cortical SVZ that were also BrdU+ at these stages (Fig. 2C, inset and Fig. 2D, inset), none were Olig2+ as described in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2G. Second, we observed that at E13.5–14.5, large numbers of Olig2+ cells appear simultaneously in the dorsolateral as well as the ventrolateral cortex, suggesting that they are not a part of the migrating stream of ventrally-derived Olig2+ progenitors (Fig. 1F, H). In contrast, the migrating Olig2+ cells of the wt cortex are distributed in a gradient with the highest density nearest to the source (i.e. ventrolateral to dorsolateral). Third, the radial alignment of the Olig2+ cells within the VZ of the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex is consistent with a dorsal origin (e.g. Fig. 3). All together, these data indicate that the ectopic Olig2+ cells in the SVZ cortex of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice arise from NPCs in the dorsal cortex.

Fig 2.

Cortical SVZ Olig2+ progenitors from NC-Brg1FL/FL mice labeled with a one hour pulse of BrdU at E13.5 or E15.5. Olig2 (red) and BrdU (green) labeled at E13.5 (A,C,E) and E15.5 (B,D,F). Insets in C (E13.5) and D (E15.5) show BrdU staining in wt animals. A number of the Olig2+ progenitors are also BrdU+ at both pulse intervals in the NC-Brg1FL/FL mice. Note that at E15.5 there are Olig2+ progenitors adjacent to the ventricular zone but few in more superficial regions of the cortex. (G) Quantification of the percentage of BrdU/Olig2 double labeled cells at E13.5 and E15.5 in wt and NC-Brg1FL/FL mice. *=p<0.01.

Fig. 3.

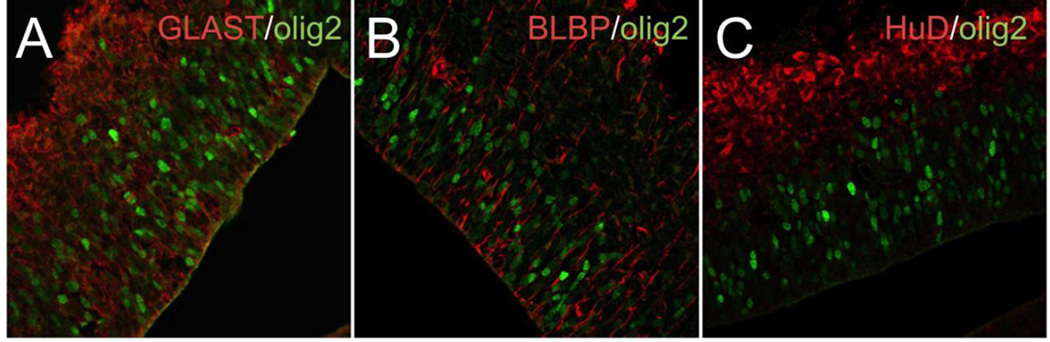

At E14.5, Olig2 immunoreactivity co-localizes with radial glial markers, GLAST (A) and BLBP (B) but not with the pan-neuronal marker HuD (C). Olig2 (green), GLAST, BLBP, HuD (red).

We were unable to determine the fate of the precocious, apparently dorsally-derived Olig2+ cells in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex. Despite their mitotic activity, they do not appear to accumulate in the cortex. Indeed their numbers decline from E13.5 onward, such that very few Olig2+ cells are detected at E17.5 (Matsumoto et al, 2006). This suggests that the early Olig2+ cells either die or differentiate into an Olig2-negative phenotype. Although, as noted earlier (Matsumoto et al, 2006; Lessard et al., 2007), cell death is elevated in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex, we did not detect co-localization of Olig2 with either cleaved-caspase 3 or TUNEL staining (not shown). Ectopic Olig2+ cells also do not express the more mature oligodendrocyte lineage markers O4 and MBP at any stage of development (Matsumoto et al., 2006). Interestingly, some of these Olig2+ cells co-express BLBP or GLAST at E13.5 (Fig. 3A, B) suggesting that they are being generated from the pool of radial glial progenitor cells of the cortical ventricular zone. However, they never express neuronal markers (Fig. 3C).

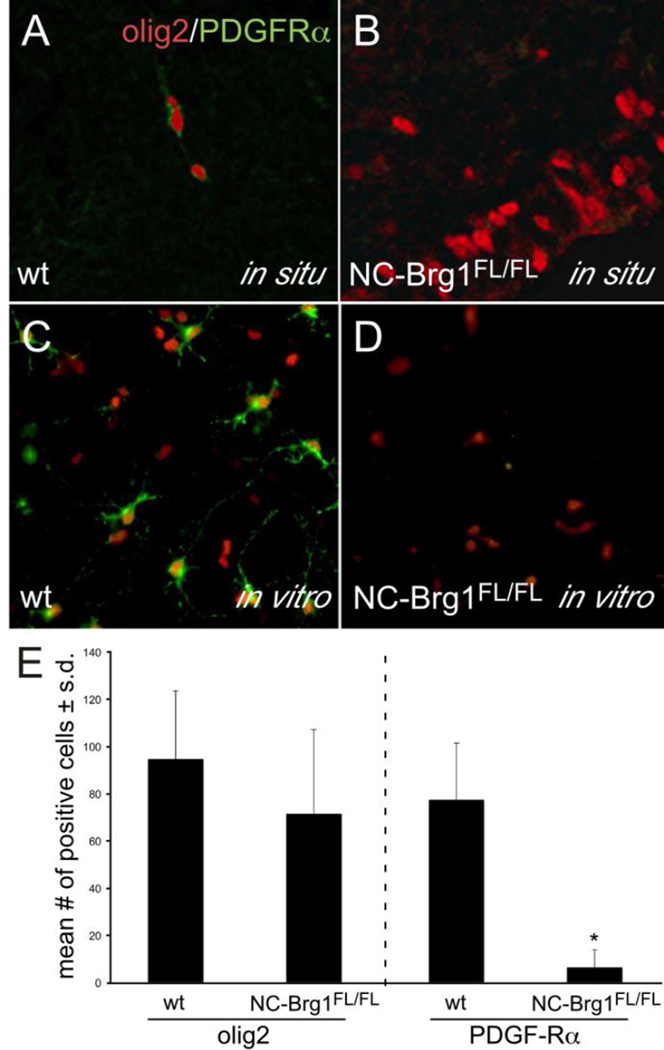

NC-Brg1FL/FL Olig2+ cells cannot be induced to differentiate into oligodendrocytes

The ventrally-derived Olig2+ progenitor cells that migrate into the cortex of wt embryos express PDGFRα during their migration (Fig. 4A). The dorsally-derived Olig2+ progenitor cells in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex rarely express PDGFRα (e.g. Fig. 4B). To test if the Olig2+ cells in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex are competent to differentiate into OPCs or mature oligodendrocytes in vitro, E13.5-E14.5 wt and NC-Brg1FL/FL cortices were dissociated then cells were allowed to adhere and were then challenged with an oligodendrocyte-differentiation medium containing T3 and PDGF (Preston et al, 2013). When NC-Brg1FL/FL or wt NPCs were placed in dissociated cell culture, the majority (>70%) of the cells expressed Olig2 (Fig. 4C, 4E). Unlike wt-NPCs, however, the vast majority of NC-Brg1FL/FL – derived NPCs could not be induced to differentiate into PDGFRα+ OPCs (compare Fig. 4C–E). In typical cultures, we found that <5% of the Olig2+ NC-Brg1FL/FL cells were also PDGFRα+ (after 72 hrs), while >70% of wt Olig2+ cells expressed PDGFRα (Fig. 4E). Unlike wt cultures, O4 and MBP, markers of more mature oligodendrocytes, were never detected in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cultures at 72 or 144 hours (not shown). All together, our findings indicate that loss of Brg1 results in the generation of ectopic Olig2+ that are largely incapable of OPC differentiation and which do not differentiate into oligodendrocytes.

Fig 4.

E15.5 cortices (A, B) and cultures of E13.5-E14.5 control (C) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (D) Olig2+ cells. Co-localization of Olig2 (red) and PDGFRα (green) in progenitor cells in vivo (A, B) and in vitro after 72 hours in oligodendrocyte-differentiation medium (C, D). (E) Quantification of Olig2+ and PDGFRα+ cells in cultures of wt and NC-Brg1FL/FL cells plated at the same densities for 72 hours. *p<0.001

Brg1 is necessary for neuroepithelial-to-radial glia cell transition but not neuronal differentiation by non-radial glial cell progenitor cells

In the developing cerebral cortex, the early NPC population consists of radial glial cells and intermediate progenitor cells (IPC) derived from radial glia. Pax6 is expressed by virtually all of the radial glial cells during the neurogenic phase of cortical development and neurogenesis is dependent upon its expression (Osumi, 2001; Simpson and Price, 2002). As discussed above, we found that Pax6 expression declines in the cortex of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice during the time when ectopic Olig2+ cells appear (Fig. 1), raising the possibilities that (a) this loss of Pax6 expression may be the result of reduced numbers of radial glial cells, and (b) that loss of Pax6 expression contributes to the generation of ectopic Olig2+ cells.

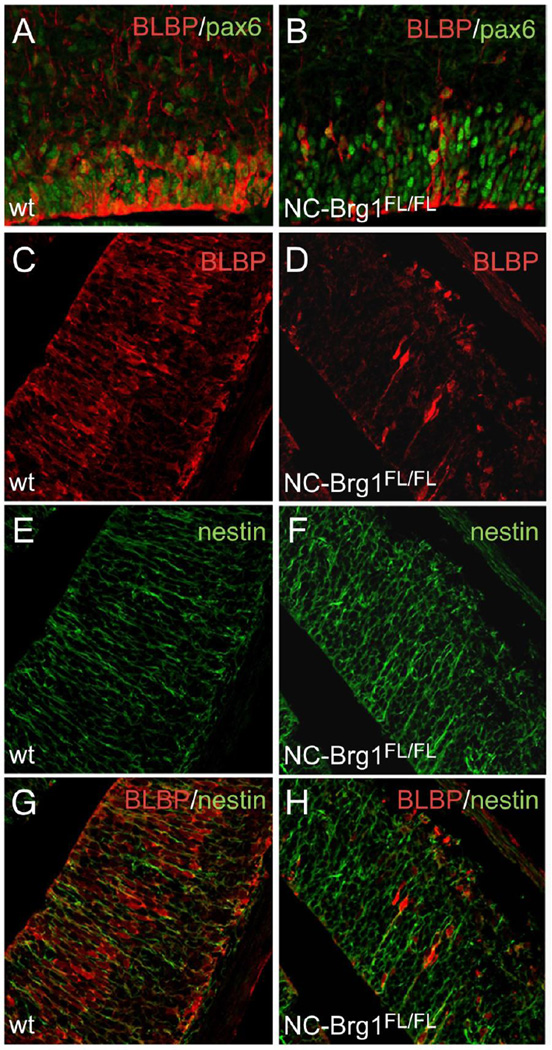

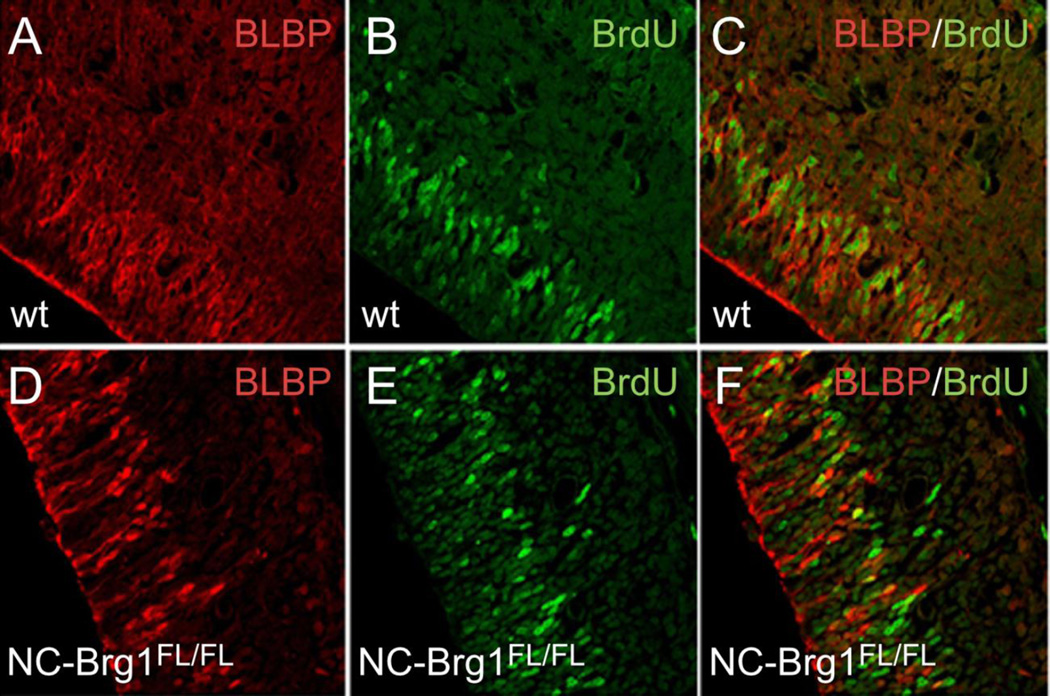

To determine if the reduction in Pax6+ cells in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice is due to reduced numbers of radial glial cell progenitors, we compared radial glial marker expression in the developing cortex of wt and NC-Brg1FL/FL animals. The reduction in Pax6+ cells is not as severe as the loss of BLBP+ radial glia in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex (Fig. 5A–D). While virtually all of the BLBP+ cells are Pax6+, the majority of Pax6+ cells do not express BLBP. This suggests that Pax6-mediated neurogenesis is occurring via cells other than radial glia (i.e. directly from neuroepithelial cells or from the intermediate progenitors of the SVZ) in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex. The density of BLBP+ radial glial cells is reduced in the NC-Brg1FL/FL mice as early as E13.5 (compare Fig. 5A, C and 5B, D) and becomes extremely sparse by E14.5 (data not shown). The loss of BLBP+ cells is more severe than the reduced RC2+ cells in the brains of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice as previously reported by us (Matsumoto et al., 2006). The RC2 epitope is expressed by neuroepithelial cells as well as radial glia (Misson et al., 1988), so we double-labeled with BLBP (radial glial cell marker) and nestin (neuroepithelial cells and radial glial cell markers) to identify both populations. With this combination of markers we detect large numbers of nestin+ cells in the NC-Brg1FL/FL mice that do not co-express BLBP (compare Fig. 5E, G and 5F, H). The majority of the radial glial cells in embryos of both genotypes are mitotically active, as indicated by a >80% BrdU labeling of BLBP+ cells following a 1 hour pulse of BrdU (compare Fig. 6A–C with Fig. 6D–F). These data indicate that radial glial cells proliferate to the same degree in both genotypes, but that Brg1 is required for the differentiation of most radial glia.

Fig. 5.

Loss of BRG1 leads to a defect in the transition of neuroepithelial cells to radial glial cells. Co-localization of BLBP (red) and Pax6 (green) immunoreactivity in the ventricular zone of E14.5 control (A) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (B) embryos. There is a profound loss of BLBP-positive progenitor cells that is more extensive than the loss of Pax6 in the NC-Brg1FL/FL animals at this stage. (C-H) Co-localization of BLBP (red) and nestin (green) immunoreactivity in E13.5 cortex. A comparison of control (C, E, G) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (D, F, H) cortex demonstrates the loss of BLBP+ radial glial cells in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex, while nestin+ neuroepithelial cells are abundant.

Fig. 6.

BLBP+ cells are mitotically active in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex. A one hour pulse of BrdU labels the majority of BLBP+ cells in wt (A–C) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (D–F) cortices. BrdU (green); BLBP (red).

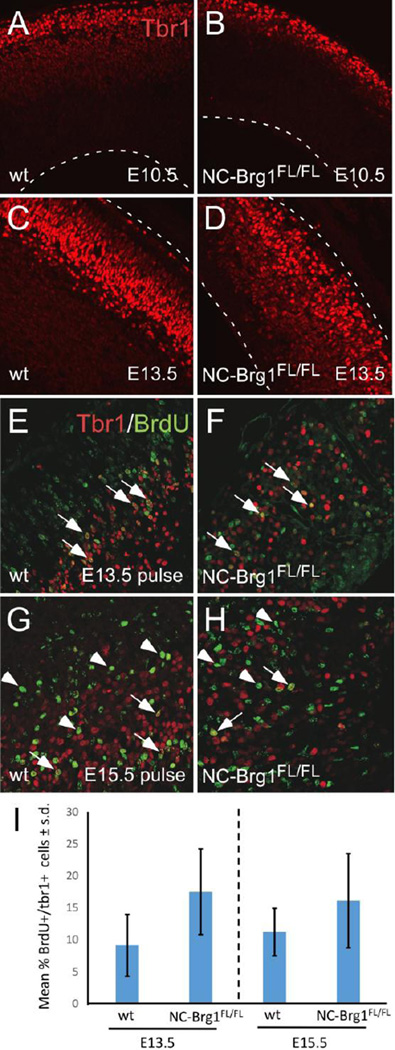

Given the alterations in Pax6 and BLBP immunoreactivity in the NC-Brg1FL/FL mice, as well as the ectopic expression of Olig2 in areas where neuronal differentiation normally occurs, we questioned whether the differentiation of specific neuronal lineages was altered in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice. In our previous study of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice, we reported that the earliest cortical neurons, the Cajal-Retzius (CR) and subplate neurons, were born normally, beginning at E10.5 (Matsumoto et al, 2006). We also reported that the formation of the cortical plate started at an appropriate stage but that neural progenitor cells in the VZ were prematurely exhausted. To further assess the extent to which neuronal differentiation is affected by the lack of Brg1, we examined the birthdates of the earliest-generated (i.e. layers V and VI) cortical pyramidal neurons and the emergence of the SVZ. The layer V/VI pyramidal neurons can be identified in embryos by the expression of the T box transcription factor, Tbr1 (Hevner et al, 2001). Tbr1 is first detected in CR cells in the marginal zone at E10.5 in both NC-Brg1FL/FL and wt mice (Fig. 7A, B). Tbr1+ neurons destined to deep layer V and VI were also detected at ~E11.5 in both wt and NC-Brg1FL/FL cortices (not shown) and Tbr1 was expressed in the expanding cortical plate (Fig. 7C, D). As the cortical plate expanded, however, the pyramidal neuron layering in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex appeared abnormal (Fig. 7D). The upper layer, Tbr1-negative pyramidal neurons were displaced or absent in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex (compare Fig 7E, F).

Fig. 7.

Cajal-Retzius (CR) and deep layer cortical neuronal differentiation occurs during a normal time interval but layers are disorganized in NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex. Tbr1 immunoreactivity (red) was examined in wt (A, C, E) and NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex (B, D, F). In both genotypes, CR and subplate neurons are born at E10.5 and migrate to the surface (A, B; see also Matsumoto, et al., 2006). At progressively later stages, layering defects become apparent in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex. At E13.5 (C, D) most of the Tbr1-immunoreactive neurons are located at the outer layer of the cortex. Dashed lines indicate borders of the tissues. (E–H) BrdU pulse labeling indicates that Tbr1+ neurons in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex are born during a period spanning E13.5 to E15.5, roughly corresponding to a normal window of deep layer neurogenesis. A one hour pulse of BrdU was administered at E 13.5 (E, F) and E15.5 (G, H) and processed at E18.5. Wt (E, G) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (F, H) cortex is shown. Note heavily-labeled BrdU-IR/Tbr1+ nuclei present after both pulses (arrows). There are also a number of heavily-labeled BrdU-IR/tbr1-negative neurons in both cortices of E15.5 pulse-labeled examples (arrowheads). Tbr1 (red), BrdU (green). (I) Quantification of percentage of BrdU/Tbr1 double labeled cells at E13.5 and E15.5. *=p<0.01

To determine the time interval of layer V/VI neurogenesis in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex, we used pulse labeling with BrdU at E11.5/12.5/13.5/14.5/15.5 or 16.5 (examining the cortices at E18.5). Heavily-labeled BrdU+ nuclei (i.e. neurons born during the pulse) co-localized with Tbr1 at all stages (e.g. pulse at E13.5; Fig. 7E, F or E15.5, Fig. 7G, H; see arrows; quantified in Fig. 7I) in both genotypes, confirming that Tbr1+ neurons were born in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex over the normal range of embryonic development (Hevner et al, 2003). Thus the initiation and termination birthdates of the deep layer, Tbr1+ cortical neurons is largely unaltered by the loss of Brg1. BrdU pulses at E15.5 also resulted in heavily-labeled neurons that were Tbr1-negative, suggesting that some upper layer neurons were being generated as well (Fig 7G, H; arrowheads; 7I).

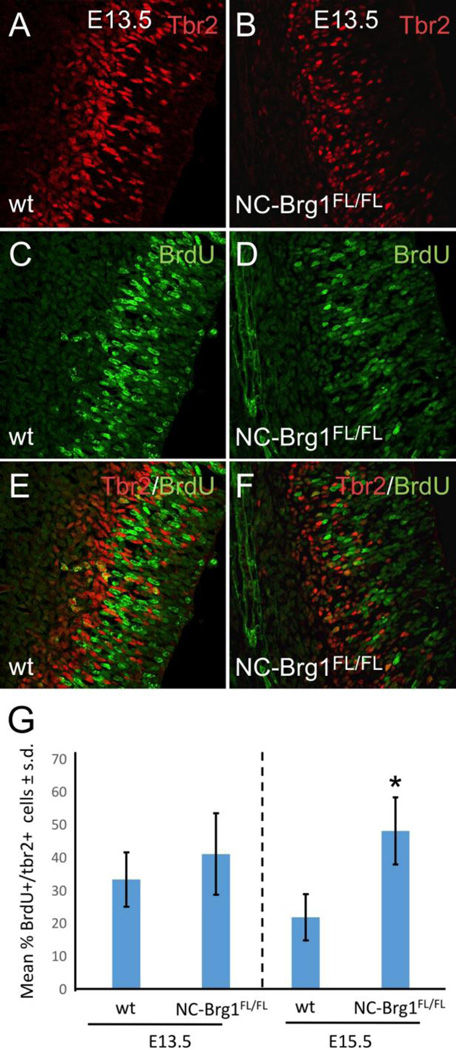

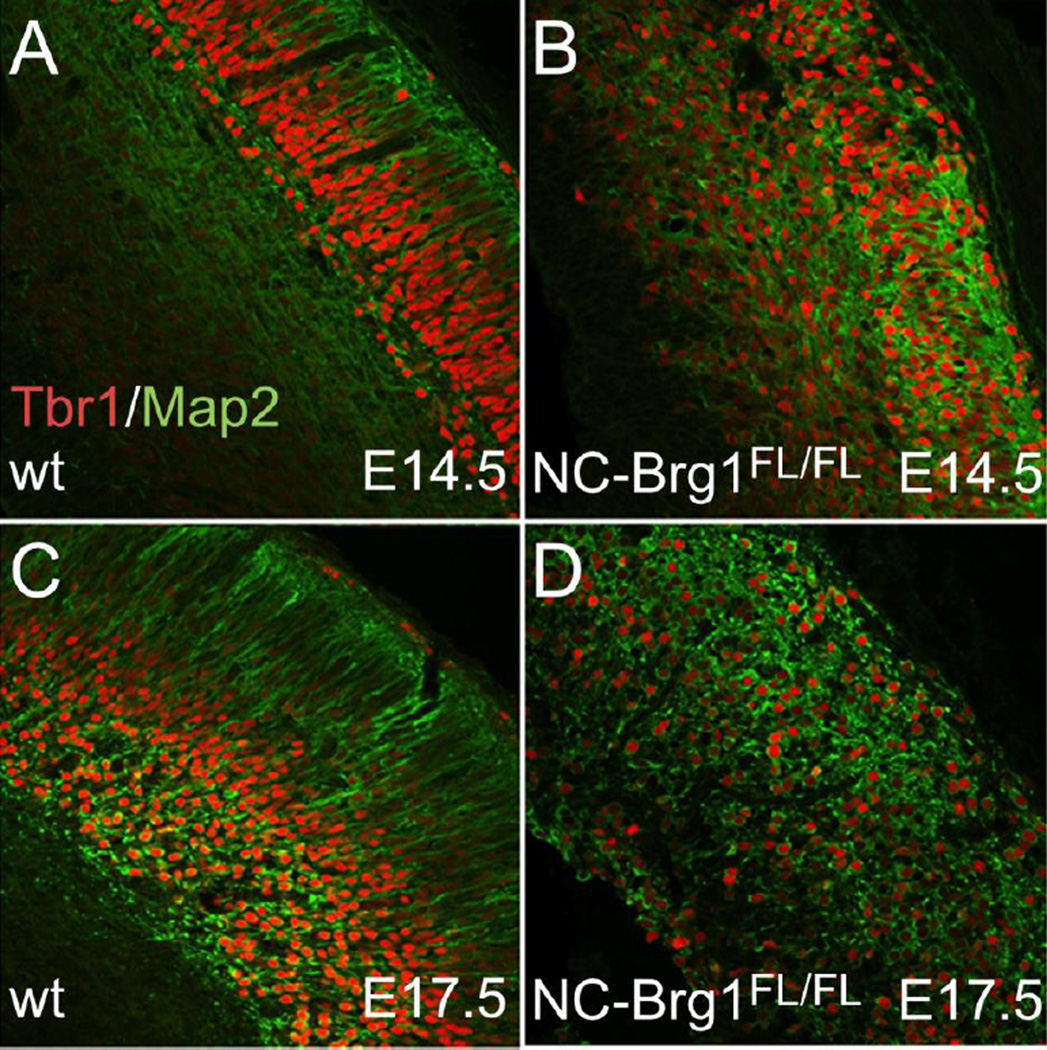

Upper layer neurons originate from the SVZ and are Tbr2+ (Arnold et al., 2008). We find Tbr2+ neurons in the NC-Brg1FL/FL as well, suggesting that this lineage is being produced at least to some extent in the mutant cortex (compare Fig. 8A, C, E and 8B, D, F). Again, pulse labeling with BrdU at E13.5 indicated that this neuronal lineage was being produced in a normal time window in NC-Brg1FL/FL embryos (Fig. 8C–G). The extent of the abnormality in cortical layer formation is apparent when the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex is labeled with Tbr1 and MAP2 (Fig. 9). Unlike wt controls, Tbr1+ neurons are scattered throughout the depth of the cortex and MAP2+ dendrites are disorganized with no apparent apical dendritic orientation with respect to the cortical surface (compare Fig. 9A, C with 9B, D). Collectively, these data indicate that Brg1 is necessary for neuroepithelial-to-radial glia cell transition and that neural progenitors lacking Brg1 can differentiate into upper and lower layer cortical neuronal populations but not astrocytes (as shown previously; Matsumoto et al., 2006) or oligodendrocytes.

Fig. 8.

Subventricular zone (SVZ) formation occurs in the absence of BRG1. The T-box factor, Tbr2 was used to identify the SVZ in wt (A, C, E) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (B, D, F) cortices. A one hour pulse label of BrdU at E13.5 (green) was followed with a double label with anti-Tbr2 (red). (G) Quantification of percentage of BrdU/Tbr2 double labeled cells at E13.5 and E15.5. *=p<0.01

Fig. 9.

NC-Brg1FL/FL embryos have abnormal cortical layering. Sections through the cortex of E14.5 (A, B) and E17.5 (C, D) wt (A, C) and NC-Brg1FL/FL (B, D) cortex labeled with anti-MAP2 (green) and Tbr1 (red). Note that Tbr1+ cells have a highly irregular distribution and that dendrites are poorly organized in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex.

Brg1 interacts directly with the Olig2 promoter and represses Olig2 transcription

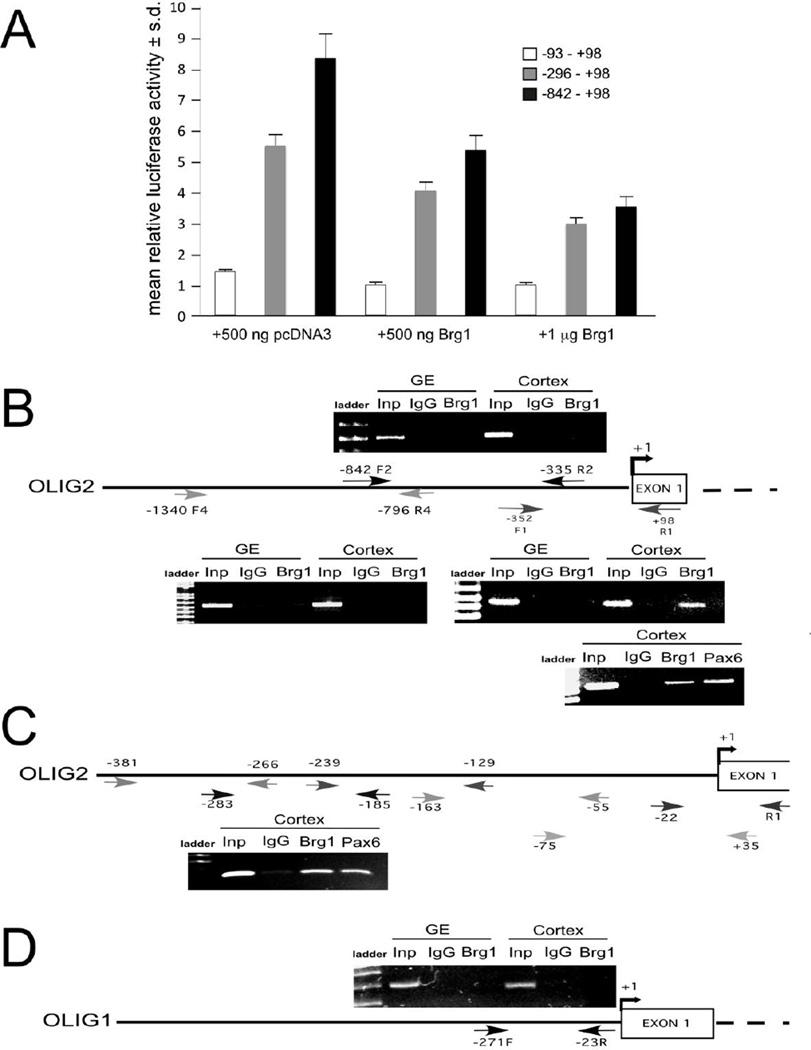

Our data indicate that Pax6 expression is diminished in the developing cortex of NC-Brg1FL/FL mice while Olig2 expression is aberrantly elevated in specific regions. Pax6 interacts with the Olig2 promoter and overexpression of Pax6 in the SVZ represses Olig2 expression (Jang and Goldman, 2011). It is therefore possible that Brg1 directly represses Olig2 expression while simultaneously promoting Pax6 expression, leading to precocious Olig2 expression in progenitor cells. To investigate the involvement of Brg1 in the regulation of Olig2, we tested if SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes that contain Brg1 directly influence Olig2 transcription. We generated luciferase reporter constructs that contained increasing lengths of the Olig2 promoter (−93, +98), (−296,+98) and (−842,+98) and co-transfected them with either an empty vector or an expression vector carrying the Brg1 cDNA into the Brg1-negative SW13 cell line (Banine et al., 2005). Brg1 significantly repressed Olig2 promoter activity in the two larger constructs (Fig. 10A). Transfection with an empty vector (Fig. 10A) or a dominant-negative Brg1 construct (not shown) had no effect on Olig2 transcription.

Fig. 10.

Brg1 interacts with the Olig2 promoter and represses Olig2 transcription. (A) Brg1 represses Olig2 transcription in a luciferase assay. Expression of luciferase driven by three different fragments of the Olig2 promoter in the SW13 cell line. Co-expression of Brg1 represses the transcription of all the constructs. (B) ChIP assay using chromation from E14.5 ganglionic eminence (GE) and cortex with different sets of primers, indicating that Brg1 binds only to the −352/+98 fragment. This Brg1 binding is only in the cortex and not in the GE. A ChIP assay using an anti-Pax6 antibody with chromatin from the cortex showed that Pax6 binds to the same −352/+98 fragment (lower right panel). (C) Pax6 interacts with the Olig2 promoter in the same region as Brg1. Shown is a ChIP assay using small fragments of chromatin(~120bp) from E.14.5 cortex and different sets of primers, indicating that Brg1 and Pax6 both bind to −283/−185 Olig2 fragment. (D) ChIP assay of the Olig1 promoter with the same chromatin used in (B) demonstrating that olig1 is not regulated by Brg1.

Brg1 may influence Olig2 transcription either directly or indirectly. We therefore performed ChIP assays using chromatin isolated from NC-Brg1FL/FL E14.5 cortex and ganglionic eminence to determine if Brg1 binds to the Olig2 promoter. We found that Brg1 associates with the Olig2 proximal promoter (−352, +98) in the cortex where Olig2 is normally not expressed and where oligodendrocyte differentiation has not begun at this stage, whereas Brg1 does not bind to the Olig2 promoter in the ganglionic eminence where Olig2 is expressed and where oligodendrocyte differentiation is first observed (Fig. 10B). No binding of Brg1 was detected in more distal fragments of the Olig2 promoter (−1340, −796 and −842,-335) (Fig. 10B). On the same ChIP, we found that Brg1 did not bind to the Olig1 promoter (Fig. 10D). We further explored where within the −352, +98 fragment Brg1 interacts with the Olig2 promoter by performing ChIP assays (with chromatin digested to small fragments of about 120 bp) using several sets of primers that could amplify about 100bp. We found that Brg1 interacts with a sequence within a −283,-185 portion of the promoter (Fig. 10C). On the same ChIP, we found that Brg1 did not bind to the Olig1 promoter (Fig. 10D). These data indicate that SWI/SNF complexes that include Brg1 interact with the Olig2 promoter and repress Olig2 expression in neurogenic progenitor cells.

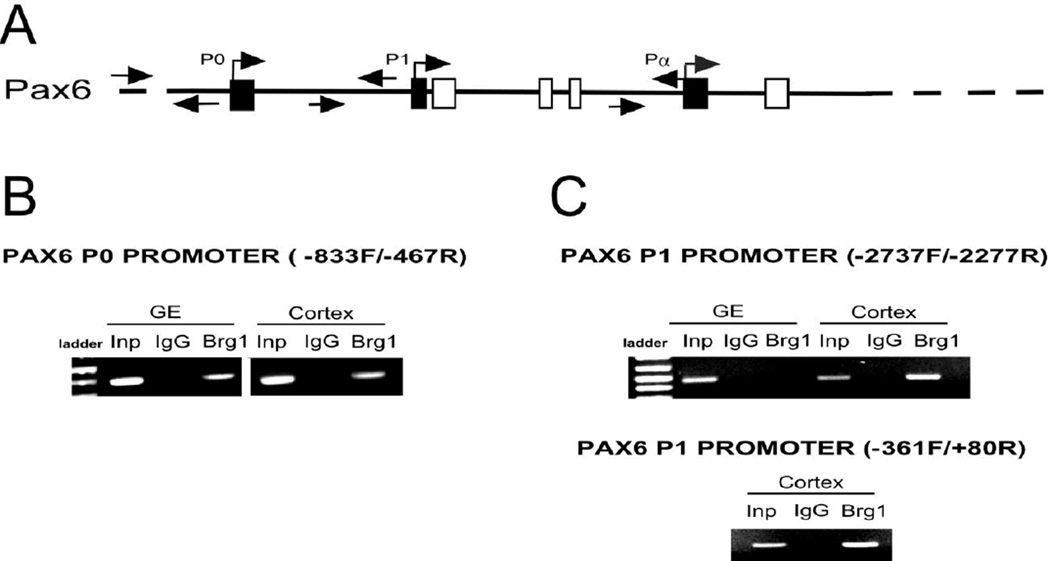

Pax6 expression is regulated by different Pax6 promoters (Fig. 11A) that influence transcription in a time- and tissue-restricted manner (Kammandel et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2002). For example, transcripts from promoter P1 are present at E8.0 in the hindbrain and caudal neural tube. At E9.5 these P1 transcripts are found in the forebrain where promoter P0 and Pα transcripts are also found by E10.5. A 5-kb mouse genomic fragment, upstream from exon 1 in the Pax6 locus was reported to drive the expression of the reporter gene in transgenic mice to the dorsal domain of the telencephalic cortex and hindbrain and in spinal cord (Jang and Goldman 2011). We performed a ChIP assay to test if there is an interaction between Brg1 and each of the Pax6 promoters (P0, P1 and Pα) (Anderson et al. 2002). We found that Brg1 interacts with Pax6 promoter P0 in the ganglionic eminence and cortex (Fig. 11B). However, we found that Brg1 binds to the P1 promoter only in the cortex (Fig. 11C). We did not find any interaction of Brg1 with promoter Pα (data not shown).

Fig. 11.

Brg1 interacts with Pax6 promoters. (A) Schematic organization and the location of different sets of primers for the Pax6 promoters P0, P1 and Pa. (B) ChIP for the P0 promoter indicates that Brg1 binds to −833/−467 fragment in the cortex and the GE. (C) In the same assay, Brg1 binds to −2737/−2277 fragment of the P1 promoter in the cortex but not in the GE. Brg1 also binds to the P1 −361/+80 fragment in the cortex.

We next tested whether Pax6 and Brg1 interact with the same parts of the Olig2 promoter. We performed a ChIP assay using chromatin from E14.5 cortex and demonstrated that Pax6 does bind to the Olig2 promoter in the same regions where Brg1 binds (−352,+98 and −283, −185) (Fig. 10B, C). We therefore examined whether there are Pax6 binding sites in this region of the Olig2 promoter. We used the Match algorithm and TRANSFAC matrices (release 2014.3; Kel et al., 2003; Matys et al., 2006) to predict transcription factor binding sites within positions −285 to −160 of the Olig2 promoter (core score >0.9; matrix score >0.8). No putative Pax6 binding sites were identified in this region of the Olig2 promoter (data not shown), raising the possibility that Pax6 may be recruited to the Olig2 promoter by Brg1 or with Brg1 by another transcription factor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transcription Factor Binding Sites in the Brg1 Binding Region of the Olig2 Promoter

| Matrix | factor name |

Position (strand) |

Core score |

Matrix score |

Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V$HSF1_01 | HSF1 | −285(−) | 0.961 | 0.878 | cgcttCTTCA |

| V$TTF1_Q5_01 | TTF-1 | −280(+) | 0.915 | 0.916 | CTTCAgc |

| V$MAFA_Q4 | MAFA | −281 (+) | 1 | 0.96 | TCAGCtc |

| V$HSF1_01 | HSF1 | −264 (−) | 0.974 | 0.894 | cgcccTTTCC |

| V$NFAT1_Q4 | NF-AT1 | −269(−) | 1 | 0.992 | cTTTCC |

| V$SP1_Q6_01 | Sp1 | −250 (−) | 0.949 | 0.818 | gtcCCTCCtc |

| V$MAZ_Q6_01 | MAZ | −250 (−) | 1 | 0.866 | gtccctCCTCCcat |

| V$SP1_Q6_01 | Sp1 | −247(−) | 0.949 | 0.89 | cctCCTCCca |

| V$MAZ_Q6_01 | MAZ | −241(−) | 1 | 0.927 | cccatcCCTCCtcg |

| V$YY1_Q6_03 | YY1 | −240(+) | 0.999 | 0.947 | CCATCcc |

| V$SP1_Q6_01 | Sp1 | −238 (−) | 0.949 | 0.81 | atcCCTCCtc |

| V$E2F_Q6_01 | E2F | −233 (+) | 0.99 | 0.877 | tcctCGCGAatc |

| V$COE1_Q6 | COE1 | −217 (+) | 0.917 | 0.823 | tacCGCGGgcgccc |

| V$RNF96_01 | RNF96 | −217 (+) | 0.953 | 0.847 | tACCGCgggc |

| V$EGR1_Q6 | Egr-1 | −215 (+) | 0.942 | 0.881 | ccGCGGGcgc |

| V$NANOG_01 | Nanog | −209(+) | 1 | 0.951 | gcgcCCATTggc |

| V$NFY_01 | NF-Y | −209 (−) | 1 | 0.974 | gcgcccATTGGctgtg |

| V$RUSH1A_02 | RUSH- 1alpha |

−207 (+) | 0.917 | 0.922 | gccCATTGgc |

| V$YY1_Q6_03 | YY1 | −205 (+) | 1 | 0.941 | CCATTgg |

| V$SOX10_Q6_01 | SOX10 | −205 (−) | 0.929 | 0.931 | cATTGGc |

| V$NF1_Q6 | NF-1 | −205 (+) | 1 | 0.97 | caTTGGCtgtgtgctgag |

| V$SREBP_Q6 | SREBP | −204 (−) | 0.906 | 0.816 | attggcTGTGTgctg |

| V$CTF_01 | CTF/NF1 | −203 (+) | 1 | 0.994 | TTGGCt |

| V$HES1_Q6 | HES-1 | −199 (−) | 0.958 | 0.818 | gctGTGTGct |

| V$REST_Q5 | REST | −199 (+) | 1 | 0.874 | gctgtgTGCTGag |

| V$DBP_Q6 | DBP | −196 (−) | 0.985 | 0.987 | gtGTGCT |

| V$MAFA_Q4 | MAFA | −194 (−) | 1 | 0.998 | gtGCTGA |

| V$MAZ_Q6_01 | MAZ | −188 (+) | 1 | 0.858 | agaGGAGGcgtgtg |

| V$SREBP_Q6 | SREBP | −187 (−) | 0.907 | 0.868 | aggaggCGTGTgccg |

| V$HES1_Q6 | HES-1 | −184 (−) | 1 | 0.821 | gagGCGTGtg |

| V$HES1_Q6 | HES-1 | −182 (−) | 0.958 | 0.967 | ggcGTGTGcc |

| V$AHR_Q6 | AHR | −182 (−) | 1 | 0.998 | gGCGTG |

| V$MECP2_02 | MECP2 | −180 (−) | 0.99 | 0.839 | cgtgtGCCGG |

| V$MECP2_02 | MECP2 | −174 (−) | 0.989 | 0.804 | ccgggCCCGG |

| V$MECP2_02 | MECP2 | −174 (+) | 0.989 | 0.804 | CCGGGcccgg |

| V$SP1_Q6_01 | Sp1 | −169(+) | 1 | 0.808 | ccGGCGGgtt |

| V$MECP2_02 | MECP2 | −169 (+) | 0.99 | 0.86 | CCGGCgggtt |

Discussion

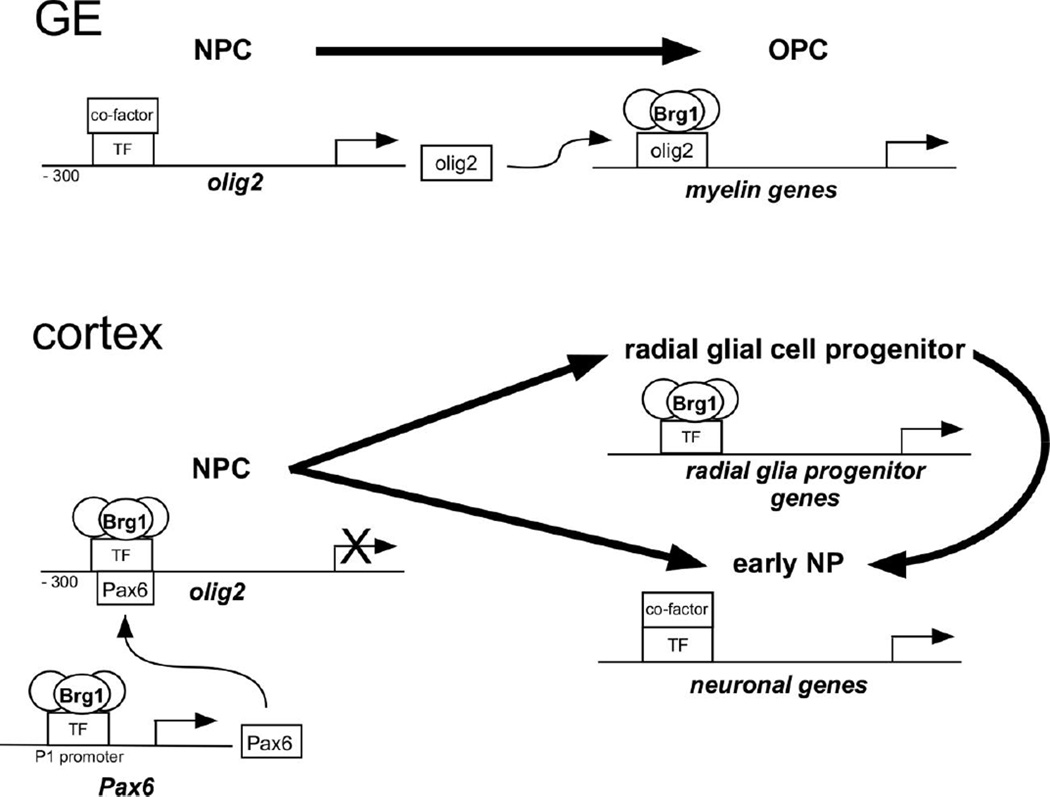

Our previous findings demonstrated that loss of Brg1 from early embryonic NPCs prevents oligodendrocyte differentiation (Matsumoto et al., 2006). A subsequent study reported that Brg1 regulates the transcription of genes required for OPC maturation through a mechanism whereby Olig2 recruits Brg1 to oligodendrocyte-specific enhancers (Yu et al., 2013). Here, we report that loss of Brg1 in early NPCs results in reduced Pax6 expression in NPCs and ectopic Olig2 expression in the developing cerebral cortex. We also find that Brg1 interacts with Olig2 and Pax6 promoters and represses Olig2 transcription but is at least partially required for Pax6 expression in the cortex. Consistent with the idea that Brg1 interacts with oligodendrocyte-specific enhancers to regulate oligodendrocyte lineage gene expression, we find that Brg1-null NPCs that express ectopic Olig2 fail to differentiate into cells in the oligodendrocyte lineage. All together these findings support a model in which SWI/SNF complexes containing Brg1 promote Pax6 transcription but repress Olig2 expression in cortical NPCs, while Brg1 is required for OPC and oligodendrocyte differentiation and maturation in Olig2-expressing progenitor cells (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

A model for the stage-specific roles of Brg1 in oligodendrogliogenesis and neurogenesis in early CNS development. In the ganglionic eminence (GE), SWI/SNF complexes with Brg1 do not interact with the Olig2 promoter in NPCs while transcription factors (TF) and co-factors that promote Olig2 transcription do interact with the promoter, resulting in Olig2 transcription. In Olig2 expressing NPCs, Olig2 recruits Brg1 to the enhancers and promoters of genes required for OPC differentiation and, later, OPC maturation into oligodendrocytes. In the cortex, SWI/SNF complexes with Brg1 interact with the Pax6 promoter and the Olig2 promoter. Together, Pax6 and Brg1 repress Olig2 transcription. NPCs then differentiate into radial glial progenitor cells, where Brg1 is required for the differentiation of early neuronal progenitors. Brg1, however, is not required for the differentiation of non-radial glial cell-derived early neurons.

Vertebrate SWI/SNF complexes contain at least 15 subunits including Brg1 and another ATPase, Brm. Brg1 and Brm are interchangeable and typically do not co-exist in the same complexes. It is possible, therefore, that Brm might replace Brg1 in SWI/SNF complexes in Brg1 null cells. However, while Brg1 null mice die at early embryonic stages (Bultman et al., 2000), Brm null mice are viable and fertile (Reyes et al., 1998). Furthermore, Brm and Brg1 appear to have non-overlapping or antagonistic roles in the differentiation of at least some cell types (Griffin et al., 2008; Flowers et al., 2009). Few studies have observed roles for Brm in neural development (reviewed by Narayanan and Tuoc, 2014). Thus, although Brm could contribute to some of the phenotypes we observe in NC-Brg1FL/FL mice, the majority of the effects are likely due entirely to the loss of Brg1 expression.

Our data showing region-specific interactions between the Olig2 promoter and Brg1 are interesting given that OPCs arise in multiple waves from ganglionic eminences, the AEP, and in the cortex, with the MGE- and AEP-derived populations becoming eliminated either just before or after birth while cortical populations go on to differentiate into oligodendrocytes (Kessaris et al., 2006). These findings are consistent with a model in which SWI/SNF complexes alter the combinatorial assembly of their subunits to achieve distinct changes in transcriptional activation in different cell populations. Indeed, such changes in SWI/SNF complex composition, and protein-protein interactions between SWI/SNF complexes and transcription factors, are required for the transition from proliferative NPCs to differentiated post-mitotic neurons or glial cells (Lessard et al., 2007; Ninkovic et al., 2013).

Although our findings and the study by Yu and co-workers (2013) suggest that Brg1 is required for OPC specification, another study reported that Brg1 is not required for the maturation of OPCs into oligodendrocytes (Bischof et al., 2015). Furthermore, these authors reported that Brg1 is required for the induction of Sox10 expression during or shortly after OPC specification, whereas maintenance of Sox10 expression at later times is independent of Brg1. Sox10 has been implicated in the terminal differentiation of OPCs (Stolt et al., 2002; Hornig et al., 2013). The study by Bischof et al. (2015) involved conditional disruption of the Brg1 gene using mice that expressed cre under the control of the Brn4 promoter, the activity of which is first detected at E8.5 in the future di- and mesencephalon, and subsequently in other areas of the nervous system (Zechner et al., 2003). In our studies, we utilized the nestin promoter to drive cre (Matsumoto et al., 2006 and this study), while Yu and co-workers utilized mice in which cre expression was driven by the Olig1 promoter (Yu et al., 2013), both of which result in recombination in early NPC populations. Collectively, these results support the idea that SWI/SNF complexes bearing Brg1 are required for the specification of OPCs but may not play an essential role in OPC maturation or the maintenance of oligodendrocytes.

Our previous study found that during the earliest stages of neurogenesis, the generation of Cajal-Retzius cells, subplate neurons and the cortical plate occurred normally in the absence of Brg1 (Matsumoto, et al., 2006). Two striking defects were the premature cessation of neurogenesis and the absence of macrogliogenesis. We determined that both deficits were due to the loss of neural progenitor cells. In the present study, we describe evidence that an early defect in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex is due to a premature loss of radial glial cells.

The intrinsically derived cortical neurons are generated from radial glial cells or intermediate progenitor cells that arise from radial glia (Englund et al., 2007). In the ventricular zone of the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex, we observe a progressive loss of Pax6 expression, a loss in BLBP+ radial glial cells and an accumulation of nestin+/Pax6-neuroepithelial cells. At the same time we observe an increase in ectopic Olig2 expression. The loss of Pax6 is consistent with the premature depletion of radial glia (Gotz et al., 1998, Jang and Goldman, 2011). Interestingly, however, the down regulation of Pax6 in the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex does not completely describe its phenotype. In the Sey/Sey Pax6 knockout, for example, radial glia are generated but they demonstrate altered morphology and cell fate (Gotz et al., 1998). In the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex, in contrast, there is a dramatic loss of identifiable radial glia that coincides with the loss of Pax6. In addition, the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex displays an accumulation of nestin+ neuroepithelial cells that has not been reported in the Sey/Sey mutant. Another link to the Pax6 knockout phenotype and the NC-Brg1FL/FL cortex is the ectopic expression of Olig2. Heins et al. (2002) reported a dramatic increase in Olig2 expression in the cortex of Sey/Sey mice. There was not a detailed analysis of radial glial cell fate in this study.

Our in silico analysis indicated that there are no putative Pax6 binding sites in the Olig2 promoter where our ChIP analyses revealed that both Brg1 and Pax6 interact. However, we identified several transcription factor-binding sites that could potentially recruit Pax6 to this portion of the Olig2 promoter (Table 2). For example, the RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) can form a complex with SWI/SNF complexes and with Pax6 (Tuoc et al., 2013). REST and a number of other factors identified in our analysis may also recruit SWI/SNF complexes containing Brg1 to the Olig2 promoter independent of Pax6. For example, the Brg1-interacting portion of the Olig2 promoter includes a binding site for the zinc-finger protein YY1, a transcriptional regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation (He et al., 2007) and YY1 could be among factors involved in how Brg1 regulates Olig2 transcription. Future studies will reveal the contributions of these candidate binding partners to Brg1-mediated neuronal and oligodendrocyte differentiation.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Loss of Brg1 results in ectopic Olig2 expression in the cerebral cortex

Olig2+ and Brg1- cells fail to differentiate into oligodendrocytes

Brg1 interacts with the Olig2 promoter in cortex but not the ganglionic eminence

Brg1 represses Olig2 transcription

Brg1 prevents precocious oligodendrocyte differentiation by neural progenitors

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Metzer and Pierre Chambon for providing the Brg1Fl/Fl mice. This study was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 NS056234) and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 4843A5/1) to LSS, and OD-011092 supporting the Oregon National Primate Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson TR, Hedlund E, Carpenter EM. Differential Pax6 promoter activity and transcript expression during forebrain development. Mech Dev. 2002;114:171–175. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ, Huang GJ, Cheung AF, Era T, Nishikawa S, Bikoff EK, Molnár Z, Robertson EJ, Groszer M. The T-box transcription factor Eomes/Tbr2 regulates neurogenesis in the cortical subventricular zone. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2479–2484. doi: 10.1101/gad.475408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banine F, Bartlett C, Gunawardena R, Muchardt C, Yaniv M, Knudsen ES, Weissman BE, Sherman LS. SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling factors induce changes in DNA methylation to promote transcriptional activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3542–3547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banine F, Matagne V, Sherman LS, Ojeda SR. Brain region-specific expression of Fxyd1, an Mecp2 target gene, is regulated by epigenetic mechanisms. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:840–851. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof M, Weider M, Küspert M, Nave KA, Wegner M. Brg1-dependent chromatin remodelling is not essentially required during oligodendroglial differentiation. J Neurosci. 2015;35:21–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1468-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, Magnuson T. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiani-Ingoni R, Coksaygan T, Xue H, Reichert-Scrivner SA, Wiendl H, Rao MS, Magnus T. Cytoplasmic translocation of Olig2 in adult glial progenitors marks the generation of reactive astrocytes following autoimmune inflammation. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki A, Weiss S. Isolation of a novel platelet-derived growth factor-responsive precursor from the embryonic ventral forebrain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10888–10899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3302-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimou L, Simon C, Kirchhoff F, Takebayashi H, Götz M. Progeny of Olig2-expressing progenitors in the gray and white matter of the adult mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10434–10442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2831-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery B, Lu QR. Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation of Oligodendrocyte Development and Myelination in the Central Nervous System. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a020461. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Fink A, Lau C, Pham D, Daza RA, Bulfone A, Kowalczyk T, Hevner RF. Pax6, Tbr2, and Tbr1 are expressed sequentially by radial glia, intermediate progenitor cells, and postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:247–251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers S, Nagl NG, Jr, Beck GR, Jr, Moran E. Antagonistic roles for BRM and BRG1 SWI/SNF complexes in differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10067–10075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808782200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz M, Stoykova A, Gruss P. Pax6 controls radial glia differentiation in the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin CT, Brennan J, Magnuson T. The chromatin-remodeling enzyme BRG1 plays an essential role in primitive erythropoiesis and vascular development. Development. 2008;135:493–500. doi: 10.1242/dev.010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Dupree J, Wang J, Sandoval J, Li J, Liu H, Shi Y, Nave KA, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. The transcription factor Yin Yang 1 is essential for oligodendrocyte progenitor differentiation. Neuron. 2007;55:217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heins N, Malatesta P, Cecconi F, Nakafuku M, Tucker KL, Hack MA, Chapouton P, Barde YA, Götz M. Glial cells generate neurons: the role of the transcription factor Pax6. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nn828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Shi L, Justice N, Hsueh Y, Sheng M, Smiga S, Bulfone A, Goffinet AM, Campagnoni AT, Rubenstein JL. Tbr1 regulates differentiation of the preplate and layer 6. Neuron. 2001;29:353–366. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Neogi T, Englund C, Daza RA, Fink A. Cajal-Retzius cells in the mouse: transcription factors, neurotransmitters, and birthdays suggest a pallial origin. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;141:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornig J, Fröb F, Vogl MR, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Tamm ER, Wegner M. The transcription factors Sox10 and Myrf define an essential regulatory network module in differentiating oligodendrocytes. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova A, Nakahira E, Kagawa T, Oba A, Wada T, Takebayashi H, Spassky N, Levine J, Zalc B, Ikenaka K. Evidence for a second wave of oligodendrogenesis in the postnatal cerebral cortex of the mouse. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:581–592. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang ES, Goldman JE. Pax6 expression is sufficient to induce a neurogenic fate in glial progenitors of the neonatal subventricular zone. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammandel B, Chowdhury K, Stoykova A, Aparicio S, Brenner S, Gruss P. Distinct cis-essential modules direct the time-space pattern of the Pax6 gene activity. Dev Biol. 1999;205:79–97. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kel AE, Gößling E, Reuter I, Cheremushkin E, Kel-Margoulis OV, Wingender E. MATCH: A tool for searching transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3576–3579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessaris N, Fogarty M, Iannarelli P, Grist M, Wegner M, Richardson WD. Competing waves of oligodendrocytes in the forebrain and postnatal elimination of an embryonic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nn1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J, Wu JI, Ranish JA, Wan M, Winslow MM, Staahl BT, Wu H, Aebersold R, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development. Neuron. 2007;55:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon KL, Kesari S, Kitada M, Sun T, Arnett HA, Alberta JA, Anderson DJ, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Development of NG2 neural progenitor cells requires Olig gene function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7853–7858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Roberts CW. The SWI/SNF tumor suppressor complex: Regulation of promoter nucleosomes and beyond. Nucleus. 2013;4:374–378. doi: 10.4161/nucl.26654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Sun T, Zhu Z, Ma N, Garcia M, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Common developmental requirement for Olig function indicates a motor neuron/oligodendrocyte connection. Cell. 2002;109:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus T, Coksaygan T, Korn T, Xue H, Arumugam TV, Mughal MR, Eckley DM, Tang SC, Detolla L, Rao MS, Cassiani-Ingoni R, Mattson MP. Evidence that nucleocytoplasmic Olig2 translocation mediates brain-injury-induced differentiation of glial precursors to astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2126–2137. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe HG, Mehta G, Zhang X, Datar I, Mehrotra A, Yeung KC, de la Serna IL. SWI/SNF enzymes promote SOX10- mediated activation of myelin gene expression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Banine F, Struve J, Xing R, Adams C, Liu Y, Metzger D, Chambon P, Rao MS, Sherman LS. Brg1 is required for murine neural stem cell maintenance and gliogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;289:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, Barre-Dirrie A, Reuter I, Chekmenev D, Krull M, Hornischer K, Voss N, Stegmaier P, Lewicki-Potapov B, Saxel H, Kel AE, Wingender E. TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D108–D110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson JP, Edwards MA, Yamamoto M, Caviness VS., Jr Identification of radial glial cells within the developing murine central nervous system: studies based upon a new immunohistochemical marker. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1988;44:95–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G, Butt SJ, Takebayashi H, Fishell G. Physiologically distinct temporal cohorts of cortical interneurons arise from telencephalic Olig2-expressing precursors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7786–7798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1807-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan R, Tuoc TC. Roles of chromatin remodeling BAF complex in neural differentiation and reprogramming. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;356:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1791-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovic J, Steiner-Mezzadri A, Jawerka M, Akinci U, Masserdotti G, Petricca S, Fischer J, von Holst A, Beckers J, Lie CD, Petrik D, Miller E, Tang J, Wu J, Lefebvre V, Demmers J, Eisch A, Metzger D, Crabtree G, Irmler M, Poot R, Götz M. The BAF complex interacts with Pax6 in adult neural progenitors to establish a neurogenic cross-regulatory transcriptional network. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:403–418. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi N. The role of Pax6 in brain patterning. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;193:163–174. doi: 10.1620/tjem.193.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston M, Gong X, Su W, Matsumoto SG, Banine F, Winkler C, Foster S, Xing R, Struve J, Dean J, Baggenstoss B, Weigel PH, Montine TJ, Back SA, Sherman LS. Digestion products of the PH20 hyaluronidase inhibit remyelination. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:266–280. doi: 10.1002/ana.23788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JC, Barra J, Muchardt C, Camus A, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Altered control of cellular proliferation in the absence of mammalian brahma (SNF2alpha) EMBO J. 1998;17:6979–6991. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TI, Price DJ. Pax6; a pleiotropic player in development. Bioessays. 2002;24:1041–1051. doi: 10.1002/bies.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolt CC, Rehberg S, Ader M, Lommes P, Riethmacher D, Schachner M, Bartsch U, Wegner M. Terminal differentiation of myelin-forming oligodendrocytes depends on the transcription factor Sox10. Genes Dev. 2002;16:165–170. doi: 10.1101/gad.215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi-Ichinose C, Ichinose H, Metzger D, Chambon P. SNF2beta-BRG1 is essential for the viability of F9 murine embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5976–5986. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Takebayashi H, Manabe T, Tanaka KF, Makinodan M, Yamauchi T, Makinodan E, Matsuyoshi H, Okuda H, Ikenaka K, Wanaka A. Genetic fate mapping of Olig2 progenitors in the injured adult cerebral cortex reveals preferential differentiation into astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:3494–3502. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schütz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuoc TC, Boretius S, Sansom SN, Pitulescu ME, Frahm J, Livesey FJ, Stoykova A. Chromatin regulation by BAF170 controls cerebral cortical size and thickness. Dev Cell. 2013;25:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Chen Y, Kim B, Wang H, Zhao C, He X, Liu L, Liu W, Wu LM, Mao M, Chan JR, Wu J, Lu QR. Olig2 targets chromatin remodelers to enhancers to initiate oligodendrocyte differentiation. Cell. 2013;152:248–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzka M, Rivers LE, Fancy SP, Zhao C, Tripathi R, Jamen F, Young K, Goncharevich A, Pohl H, Rizzi M, Rowitch DH, Kessaris N, Suter U, Richardson WD, Franklin RJ. CNS-resident glial progenitor/stem cells produce Schwann cells as well as oligodendrocytes during repair of CNS demyelination. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner D, Fujita Y, Hülsken J, Müller T, Walther I, Taketo MM, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C. beta-Catenin signals regulate cell growth and the balance between progenitor cell expansion and differentiation in the nervous system. Dev Biol. 2003;258:406–418. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SC, Lundberg C, Lipsitz D, O’Connor LT, Duncan ID. Generation of oligodendroglial progenitors from neural stem cells. Neurocytol. 1998;27:475–489. doi: 10.1023/a:1006953023845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factors OLIG2 and OLIG1 couple neuronal and glial subtype specification. Cell. 2002;109:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]