Abstract

Genetically encoded optical sensors of cell activity are powerful tools that can be targeted to specific cell types. This is especially important in neuroscience because individual brain regions can include a multitude of different cell types. Optical imaging allows for simultaneous recording from numerous neurons or brain regions. Optical signals of membrane potential are useful because membrane potential changes are a direct sign of both synaptic and action potentials. Here we describe recent improvements in the in vitro and in vivo signal size and kinetics of genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) and discuss their relationship to alternative sensors of neural activity.

Keywords: genetically encoded voltage indicators, GEVIs, genetically encoded calcium indicators, GECIs, Ehud Isacoff, Thomas Knopfel

Optical measurement of neural activity - realizing Sherrington’s dream

Optical measurements of brain activity are attractive because they allow for simultaneously monitoring of activity from many individual neurons or from many different brain regions (population signals). In 1937 Sherrington[1] imagined points of light signaling the activity of nerve cells and their connections. During sleep only a few remote parts of the brain would twinkle. But at awakening, “Swiftly the head-mass becomes an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern.” In the 80 years since this poetic description there have been significant advances towards making optical measurements of neural activity a reality. Here we attempt to explain why genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) (see Glossary) would be useful towards this end and describe recent progress in developing improved sensors with larger and faster signals. We also compare GEVI signals with those from genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs).

GEVIs have been used in vivo for measurement of spike activity from individual cells and for measurement of population signals. With exceptions, [2] [3, 4] most of the individual neuron recordings have been from invertebrates [5] [6] [7, 8] while population signals have been measured from mammalian preparations (e.g., [9, 10] [11] [12] ). This review emphasizes (is restricted to?) recordings from mammalian preparations. For earlier reviews of GEVIs see [13, 14, 15].

Tuning optical reporters of neural activity

The membrane potential changes of neuronal cells can vary dramatically from hyperpolarizations during neuronal inhibition to depolarizations from excitatory synaptic activity to the firing of action potentials. These different kinds of membrane potential change can complicate the interpretation of GEVI optical signals from populations of neurons especially in situations where different cell types have different kinds of activity. Restricting the response of a GEVI to one type of activity (e.g., inhibition or action potentials) would facilitate the analysis of population signals. The voltage sensitivity of mosaic GEVIs (see below), with sigmoidal fluorescence vs voltage relationships, can be ‘tuned’ to respond to specific voltage ranges and thus report specific types of neuronal activity [16, 17] In addition there are different kinetic requirements for measuring different kinds of neuron activity. Measuring synaptic signals require a high dynamic range indicator but only low (> 10 ms) temporal resolution. In contrast action potentials can be measured with lower dynamic range but fast (< 1 ms) temporal resolution.

Calcium indicators

Beginning in 2003 [18], calcium signals have been used as a surrogate for a direct measure of action potentials on the assumptions that action potentials are the only source of the measured calcium changes and that calcium changes occur during action potentials in all types of neurons. These assumptions are certainly not universally true [19, 20] but none-the-less calcium signals are widely used as indicators of spike activity. This is due to a combination of the large signal-to-noise ratios of genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) and, until recently, the quite small signal-to-noise ratios of GEVIs. Furthermore, calcium changes and the resulting signals are much slower and thus are better suited to the frame rates available in 2-photon imaging. Recent reviews of calcium imaging and GECIs are available elsewhere [21, 22, 23]

Following a brief history of the development of GEVIs we describe the varieties of GEVI structures that have been explored and present results from 11 different probes including one example GEVI from each of the laboratories developing GEVIs (Table 1). Following a discussion of four characteristics of these probes we then present examples of GEVI function in cultured HEK293 cells, cultured neurons, and both cellular and population in vivo measurements. We then present evidence that voltage sensitive intermolecular FP interactions underlie the fluorescence change of some mosaic GEVIs. Lastly, we compare GEVIs with GECIs.

Table 1.

Properties of selected GEVIs

| ΔF/F for a 100 mV depolarization (HEK293 cells) | Fast ON tau (100 mV depolarization (ms) | Approximate quantum yield | Single trial signals in neurons | Single trial in vivo signals | Comments | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mosaic single FP GEVIs | |||||||

| ArcLight | 40% | 10 | 1 | yes | yes | [5, 12, 27] | |

| Bongwoori | 20% | 8 | 1 | yes | not tested | [17] | |

| ASAP1 | 17% | 2 | 1 | yes | not tested | [29] | |

| Arclightning | 10% | 10 | 1 | not tested | not tested | faster OFF | [60] |

| mosaic butterfly GEVIs | |||||||

| Nabi2.213 | 11% | 3 | 1 | yes | not tested | PC12 cells | [58] |

| VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 | 4% | 2 | 1 | not tested | yes | [28] | |

| Mermaid2 | 20% | 2 | 1 | yes | yes | [10] | |

| microbial-rhodopsin GEVIs | linear F vs V | ||||||

| Archer1 | 80% | 2 | 0.01 | yes | yes | cultured neurons; C. elegans | [6] |

| QuasAr2 | 90% | 1 | 0.01 | yes | not tested | [39] | |

| Ace2N-4AA-mNeon | 8% | 0.4 | 1 | yes | yes | mosaic | [4] |

| two component GEVIs | |||||||

| hVOS | 30% | 0.5 | 1 | yes | not tested | PC12 cells; linear F vs v | [32, 61] |

GEVI history

The first human-made GEVI was a mosaic constructed by inserting a fluorescent protein (FP) into a voltage sensitive protein residing in the plasma membrane. The sensor, FlaSh, [24], was a voltage gated potassium channel with GFP inserted following the 6th transmembrane segment. Aside from its importance as a proof-of-principle, FlaSh had the useful feature of a steep, sigmoidal fluorescence vs voltage relationship that could be tuned to select for different ranges of membrane potential. However, FlaSh also had drawbacks; its signal was relatively slow (tau ~100 msec), and small (ΔF/F <5%). But, most importantly, FlaSh, and the analogue Flare [25], worked in frog oocytes but not at all in mammalian cells. In mammalian cells, Flare’s expression, and that of two other first generation GEVIs that were also based on mammalian ion channels, was mainly intracellular [25]. This obstacle was overcome by changing the membrane resident voltage sensor to the voltage sensitive domain of the Ciona intestinalis voltage sensitive phosphatase [16]. The first member of this family, VFSP2.1, expressed well in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells and signaled changes in membrane potential. However, the Ciona voltage sensitive domain exhibits a gating current that lies far outside of the physiological voltage range [26]. The R217Q mutation shifted the voltage curve to a physiological range [16] but made the sensor slower [17].

Comparison of GEVI structures

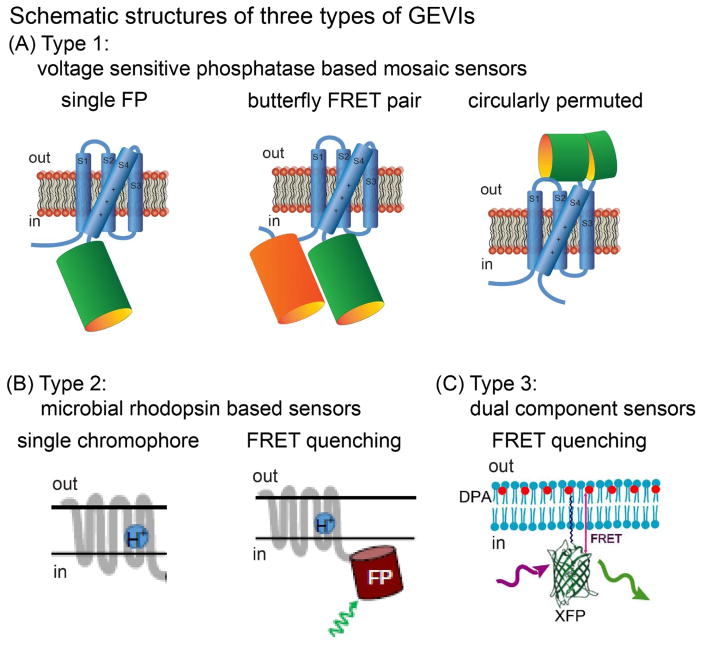

A number of recent GEVI developments have focused on mosaic proteins using the voltage sensitive domain of the Ciona voltage sensitive phosphatase as well as analogues from other vertebrate species. Three varieties of mosaic GEVIs are illustrated schematically in Figure 1A. The left panel illustrates a single fluorescent protein (FP) mosaic (example, ArcLight; [27] ); the middle panel a mosaic with a “butterfly” FRET pair [28] of fluorescent proteins, where the two FPs are on opposite sides of the voltage sensitive domain (example, VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 [28],) and the right panel a mosaic with a circularly permuted fluorescent protein inserted in the external loop between transmembrane segments 3 and 4 (example, ASAP1; [29] ).

Figure 1.

Schematic structures of three types of GEVIs. (A). Mosaic sensors combining the voltage sensitive domain of a voltage sensitive phosphatase and a fluorescent protein. (B). Sensors based on the voltage sensitivity of a microbial rhodopsin. (C). Sensors that are a combination of two separate molecules. Figure 1B was modified from [62] ). Figure 1C was modified from [32]

A second type of GEVI utilizes the voltage sensitivity of microbial rhodopsins (Figure 1B; [30] ). Both the absorption and fluorescence of the microbial rhodopsins are voltage sensitive but their fluorescence quantum efficiency is ~100 times smaller than GFP and thus GEVIs that are composed of the single microbial rhodopsin chromophore (left panel) require high intensity illumination to achieve an adequate fluorescence signal-to-noise ratio (example, Arch; [31] ).

By combining the microbial rhodopsin in a mosaic with a second, bright, fluorescent protein (Figure 1B, right panel) a voltage sensitive FRET quenching signal is obtained (example Ace2N-4AA)-mNeon [4] ). A third type of GEVI is a two component sensor that utilizes FRET quenching between a membrane bound fluorescent protein and a charged membrane resident molecule as the voltage sensor (Figure 1C; example, hVOS; [32] ). The voltage sensor, dipicrylamine, in hVOS has to be externally applied by the experimenter.

Signal characteristics of 11 different GEVIs

Table 1 lists three important characteristics of 11 GEVIs from 11 different laboratories. The Table includes representatives of all six structural types illustrated in Figure 1. Because the fractional fluorescence change, ΔF/F (first column), was measured with relatively long (~100 msec) voltage steps, these values are most informative concerning the ability of the GEVI to detect relatively slow changes in membrane potentials. (We report values of the fractional fluorescence change, ΔF/F; the fractional ratio change, ΔR/R, is only applicable to sensors with two-component FRET signals).

The ability to detect fast action potentials will depend on both the ΔF/F and the speed of the response (second column). Clearly, some sensors (e.g. Ace2N-4AA-mNeon) are fast enough to accurately follow the time course of mammalian action potentials while slower sensors (e.g. ArcLight) will have a smaller signal size for action potentials than might be expected from its ΔF/F value.

In addition, several other factors affect the signal-to-noise ratio of the measurements. One is the brightness of the fluorophore. In the GEVIs under consideration the brightness is largely determined by the fluorescence quantum yield (third column). The single chromophore microbial rhodopsin GEVIs have quantum yields ~100 fold smaller than other GEVIs. In principle, the reduced signal-to-noise ratio resulting from the lower quantum yield can be compensated for by a 100 fold increase in illumination intensity. However, the higher illumination intensity will result in an increased intrinsic fluorescence and heating in in vivo measurements in mammalian brains. Thus far, these single chromophore microbial rhodopsin GEVIs have not been used to measure activity in mammalian preparations

Lastly, membrane expression, a poorly quantified parameter, makes an important contribution to both the ΔF/F and the signal-to-noise ratio. All of the images of GEVI expression that we are aware of have substantial intracellular expression. The first generation GEVIs expressed well in frog oocytes but not in mammalian cells [25]. Mermaid expressed well in HEK293 cells but not in neurons [33, 34]. The linker length in the Ace2N-mNeon series had to be adjusted to optimize expression in culture, in slice, and in vivo [4]. The factors controlling GEVI membrane expression in different cell types remain poorly understood.

The fourth and fifth columns of Table 1 indicate whether action potential signals have been measured in cultured neurons and whether activity signals have been measured in vivo.

FRET-based GEVIs that are ratiometric (i.e. with two similarly bright FPs) have the advantage that the ratio removes common mode noise due to movement, e.g., respiration and blood flow. However, the fluorescent intensities of the donor and acceptor FPs are often different, which means the shot noise of the ratio will be higher than that of either individual signal [35, 36]. FRET quenching microbial rhodopsin signals are not ratiometric because there is only a single optical signal (from the fluorescent donor).

Examples of GEVI signals in cultured HEK293 cells, in cultured neurons, and in vivo

GEVI signals in HEK293 cells: example: ArcLight, a single FP mosaic protein [27]

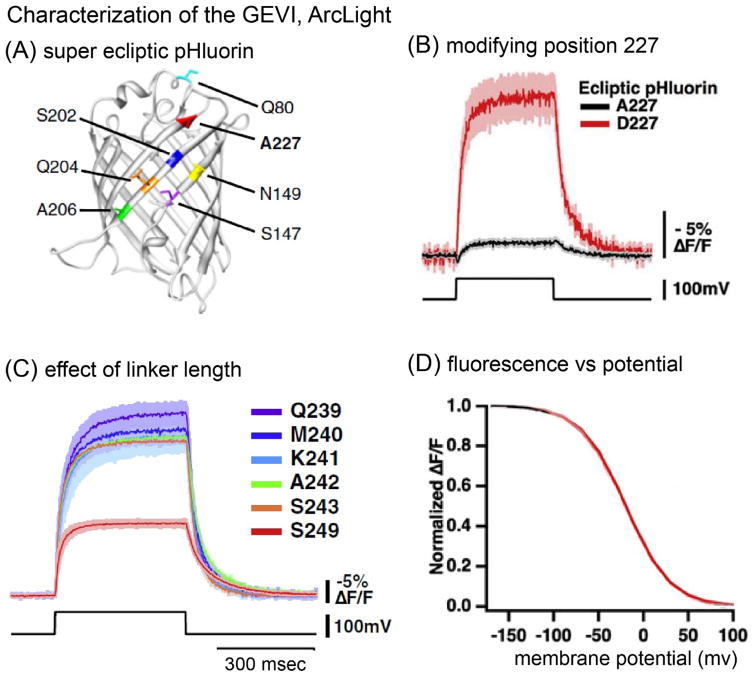

Serendipity resulted in ArcLight, a mosaic of the Ciona voltage sensitive domain and the GFP derivative, super ecliptic pHluorin [37] A227D. Figure 2A shows the location of A227. The black trace in Figure 2B shows the response to a 100 mV depolarization in a HEK293 cell using the native super ecliptic pHluorin. The red trace is the response with the spontaneously occurring A227D mutation. This mutation increased the signal size by a factor of 15. The signal size was increased by another factor of 2 by shortening the linker between S4 and the fluorescent protein resulting in a ΔF/F of ~40% per 100 mV (Figure 2C). This ΔF/F was five times larger than the previous largest [33, 38] GEVI signal.

Figure 2.

Characterization of ArcLight, a single FP mosaic sensor. (A). The location of the outward facing A227 amino acid. (B). The A227D mutation increased the signal size by a factor of 15. (C). A further increase in signal was found if the linker between the S4 segment and the FP was shortened. (D). The fluorescence change vs membrane potential was sigmoidal with a V1/2 of −20 mV. Modified from [27].

Figure 2D is a plot of the ArcLight fluorescence signal vs membrane potential. The V1/2 for the fluorescence change is −20 mV. Thus ArcLight will be maximally sensitive to membrane potentials that occur during action potentials but will still have some sensitivity to changes near the resting potential. Other mutations to the Ciona voltage sensitive domain could make the GEVI more sensitive to synaptic potentials or to inhibition ([17] ).

ArcLight’s kinetics are not fast; the response to a step change in membrane potential is best fit by two components (see Figure 2B,C) with time constants of ~10 and ~50 msec at 33°C. As a result, ArcLight signals during action potentials will not be as large as those found in response to longer voltage clamp steps [27].

GEVI spike signals in cultured neurons: example QuasAr2; a single chromophore microbial rhodopsin GEVI [39]

The kinetics of QuasAr2 are substantially faster than those of ArcLight. The QuasAr2 signal is also best fit by two exponentials with a fast time constant of 0.3 msec and a slow time constant of 3 msec at 34°C. Because of its faster time constants, the QuasAr2 action potential signals are expected to more closely follow the time course of the action potential and the size of the action potential signal is expected to be closer to the size expected from 100 msec voltage clamp steps. These expectations are confirmed by the QuasAr2 signal shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A simultaneous optical and electrode measurement of an action potential in a cultured hippocampal neuron using QuasAr2, a single chromophore microbial rhodopsin GEVI. Modified from [62].

Even though the fluorescence quantum efficiency of QuasAr2 and other single chromophore microbial rhodopsins GEVIs is ~100 times smaller than that of ArcLight, the signal-to-noise ratio for the action potential recording in Figure 3 is large. This was achieved by using a high intensity incident light, 200Wcm−2, ~100 times brighter than that used for GFP based GEVIs. The dim fluorescence of single chromophore microbial rhodopsins is likely to limit their use in vivo mammalian preparations. QuasAr2, like the other microbial rhodopsin signals, has a linear fluorescence vs membrane potential relationship [31, 39] and thus they cannot be tuned to detect specific kinds of potential changes in a population measurement.

Individual cell GEVI signals in vivo: example Ace2N-4AA-mNeon, a microbial rhodopsin FRET quenching GEVI. [4]

Measuring GEVI spike signals from individual neurons in the in vivo mammalian brain has been challenging because light scattering blurs the image of individual cells in a wide-field measurement and 2-photon imaging of appropriate 2-dimensional frames is too slow. By combining a very fast GEVI together with sparse expression, spike signals from individual neurons were measured from cells in the upper 150 μm of mouse cortex (Figure 4). Phototoxicity and photobleaching were minimal allowing for long recording times. [4]

Figure 4.

In vivo individual neuron spikes measured in a layer 2/3 visual cortical neuron of an awake mouse using Ace2N-4AA-mNeon, a microbial rhodopsin FRET quenching GEVI. The spike signals are riding on top of longer lasting depolarizations. Modified from [4].

Population GEVI signals in vivo: example ArcLight, a single FP mosaic protein [12]

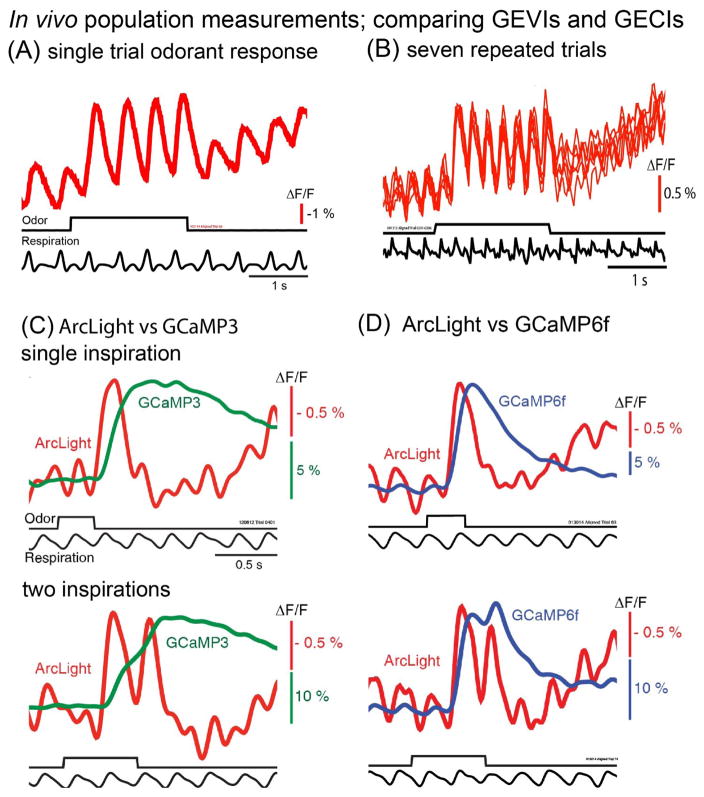

AAV1 transduction was used to express ArcLight in the mouse olfactory bulb [12]. In the outer layers of the bulb the expression was specific for mitral/tufted neurons. Figure 5A illustrates a single trial, single glomerulus mitral/tufted response to an odorant stimulus that lasted for four inspirations. During each breath the ArcLight signal increased and then returned toward the baseline. This measurement reflects the population average of the optical signals from ~50 mitral/tufted cell dendrites in a glomerulus and is the expected result from action potential recordings from mitral/tufted cells which spike only during the inspiration phase [40]. Repeated trials gave similar results (Figure 5B) indicating that phototoxicity and photobleaching were minimal.

Figure 5.

(A,B) In vivo population measurements using ArcLight, a single FP mosaic GEVI. The mitral/tufted cells were transduced by infection with an AAV1 virus containing ArcLight DNA. (A). A single trial, single glomerulus measurement of the response to the odorant ethyl tiglate presented during four breaths. (B). The overlay of the responses to six repeated trials. There was little change from trial to trial. (C). Comparing ArcLight and GCaMP3 signals from opposite olfactory bulbs in the same preparation in response to odorant presentations lasting one and two breaths. (D). Comparing ArcLight and GCaMP6f. Modified from [12].

Choosing a GEVI for in vivo measurements

Not enough information is available to allow a reliable recommendation. Although Table I includes 11 different GEVIs, only four of the 11 have been tested in in vivo mammalian measurements. Because ArcLight has a signal size that is much larger than VSFP-Butterfly 1.2, but has similar kinetics and quantum yield (Table 1), one might expect that ArcLight’s in vivo signal would be larger than that of VSFP-Butterfly 1.2. And, indeed, ArcLight’s signal is larger. ArcLight has a large signal-to-noise ratio in individual trials (Figure 5B) while 10–20 trials have most often been averaged for VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 signals [9, 28, 41]. However, this in vivo comparison of ArcLight and VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 was not direct. The transformation method (virus vs electroporation), the cell type, the brain region, and the physiological stimulus were different. It is possible that VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 has better expression and membrane targeting than ArcLight and thus ArcLight and VSFP-Butterfly 1.2 could be equivalent in vivo. Clearly, comparisons of different GEVI’s in the same experimental preparation are needed.

Mechanisms underlying a single FP mosaic GEVI signal

The development of better GEVIs may be facilitated by determining the mechanism(s) that couple changes in membrane potential to changes in fluorescence. FRET-based constructs are superficially easy to understand: movements of the voltage sensing domain change the distance and/or orientation of the donor and acceptor chromophores resulting in a change in FRET. The fluorescence changes of probes with circularly permuted FPs such as ASAP-1 [29] and Electric-PK [52] are also theoretically straightforward (movement of S4 alters the β-barrel structure). However, an explanation for the optical signal from mosaic GEVIs which consist of a single FP residing in the cytoplasm is not obvious. How does the movement of the S4 transmembrane domain cause a fluorescent signal from a cytoplasmic FP? The results presented below suggests a surprising hypothesis.

Because super ecliptic pHluorin is pH sensitive, a possible mechanism for the fluorescence change involves pH. Only super ecliptic pHluorin was able to give large optical signals when the A227D mutation was present. The A227D mutant does not improve the optical signal for other FPs such as Clover, eGFP, or YFP [53]. However, large signals from eGFP were obtained by introducing the A227D mutation along with three other mutations found in super ecliptic pHluorin [53]. These mutations converted eGFP into a pH-sensitive FP suggesting that these GEVIs might be measuring pH. However, a single mutation that increased the pH sensitivity did not result in a large signal [53] Furthermore, Kang and Baker [54] measured a voltage-dependent optical signal and a pH-dependent signal simultaneously using the voltage-sensing domain of a voltage-gated proton channel fused to super ecliptic pHluorin A227D. A 200 mV depolarization resulted in the activation of the voltage-gated proton current which slowly decreased the internal pH of the cell resulting in a slow increase in fluorescence. A 100 mV depolarization did not activate the proton channel and only a voltage-dependent change in fluorescence was observed. Increasing the buffering capacity of the internal patch solution inhibited the pH-dependent fluorescence change but had no effect on the voltage-dependent signal. These observations strengthen the conclusion that ArcLight and related analogues are not sensing membrane potential via a change in pH.

Hints for a different mechanism were first suggested during the development of ArcLight. Surprisingly, A227D resides on the outside of the β-barrel structure suggesting that this mutation does not directly interact with the chromophore. Second, another hint to potential mechanism was given by the fact that the signal could be improved by optimizing the length of the amino acid linker between the cytoplasmic FP and the S4 transmembrane domain ([27, 53]. Both the linker length and the amino acid composition at the fusion site of the FP and the linker affected the optical signal, suggesting that the orientation of the FP was important [51]. These results led to the hypothesis that the super ecliptic pHluorin in ArcLight is interacting with the FP from an adjacent ArcLight protein. The movement of S4 then alters that interaction resulting in the change in fluorescence.

There are three mutations to eGFP that favor the monomeric version of the FP, A206K, L221K and F223R [55]. The GEVI TM [17], an analogue of ArcLight, with 206A-221L-223F mutations which favor dimerization has the largest signal (Figure 5, orange trace). Individual mutations favoring the monomer at the three sites reduced the signal; double mutations cause a further reduction (Figure 5). These data strongly support the hypothesis that movement of the S4 domain alters the dimerization interaction thus resulting in the change in fluorescence.

Concluding Remarks

Developing improved GEVIs is both unpredictable and challenging yet success seems likely. Several results (e.g. Figures 2 and 6, [16] ) have shown that changing individual amino acids in either the voltage sensitive domain or in the fluorescent protein of a mosaic GEVI can have dramatic effects on performance. Similarly, the location of the FP in the voltage sensitive domain also has dramatic effects on GEVI function [29, 58]. Improving GEVIs involves investigations in a large multi-parameter space. Furthermore, it is not often that a planned mutation in a GEVI has the planned result. The situation is further complicated by the fact that many different characteristics of the GEVI are important for its functionality. As a result high-throughput methods for improving GEVIs have thus far concentrated on individual characteristics (e.g. brightness [39] ).

Figure 6.

The effect of monomeric mutations at the dimerization site of a single FP mosaic GEVI. A. The GEVI TM with 206A-221L-223F which favor dimerization has the largest signal (orange). Individual mutations favoring the monomer at the three sites reduced the signal; double mutations cause a further reduction. B. A schematic model of a TM dimer. Modified from [59].

At the same time, the opportunities for improving GEVIs are also very large because investigation of the multi-parameter space is only just beginning and, as Figure 1 and Table 1 indicate, many approaches are under active investigation. In addition, Kang et al [59] provide evidence that an unanticipated dimerization mechanism is responsible for some single FP mosaic GEVI signals. This finding is likely to guide further attempts at improvement of mosaic GEVIs.

Future development is needed in two new directions. First, to provide better GEVIs with red signals so that simultaneous measurements could be made from two cell types or simultaneous stimulation and recordings could be carried out in the same brain region. Second, to target GEVIs to specific regions of the neuron so that the optical signal could be specific for nerve terminals, or dendrites, or the soma. This would improve the signal-to-noise ratio in many kinds of measurements.

Thus far GEVI publications have emphasized improvements in sensor characteristics and proof of principle measurements in in vivo preparations. We are optimistic that the future will include the use of these improved GEVIs to obtain new insights into brain function.

Box 1. Comparison of GEVIs and GECIs as indicators of neural activity.

Population signals

Paired recordings of ArcLight and GCaMP3 in the same preparation in response to one and two inspirations of ethyl tiglate are shown in Figure 5C. A similar comparison of ArcLight and GCaMP6f is shown in Figure 5D. The longer odor presentations resulted in breath coupled responses that were very obvious with ArcLight, but relatively small with both GCaMPs. These are population signals; both ArcLight and the GCaMPs are in the glomerular dendrites of ~50 mitral/tufted cells which innervate each glomerulus. Clearly, ArcLight had a smaller ΔF/F and signal-to-noise ratio than the GCaMPs. However, ArcLight had a faster onset, rise time, and decay than the GCaMPs and could track the odor-evoked signal across successive inspirations of an odor[12]. In contrast, the GCaMP measurements were saturating integrals of the odor-evoked neural activity. GEVI signals (VSFP-Butterfly 1.2) and GECI signals (GCaMP3) in visual cortex were compared in response to visual stimuli [41]. In some circumstances (brief stimuli) the GECI had a much larger signal-to-noise ratio while for steady state stimuli the GECI and GEVI signal-to-noise ratios were similar.

Cellular signals

Figure 4 shows that the fast GEVI, Ace2N-4AA-mNeon, can track individual spikes with excellent timing resolution and can do so at spike rates much higher than possible using GECIs.

Because action potentials sometimes cause large influxes of calcium mediated by voltage-gated calcium channels [42] [43], calcium dyes and GECIs are commonly used as surrogates for voltage dyes and GEVIs in detecting action potentials in individual mammalian neurons. The calcium sensors have the important advantage of a large signal-to-noise ratio. However, voltage-gated calcium channels are not the only source of calcium entry in a cell, and thus calcium signals do not always reflect spike activity. For example, subthreshold depolarizations elicited clear calcium transients in mitral cells [19]. Calcium influx can also occur through ligand-gated receptors [44] [23] and can be further modulated by release from internal stores of calcium [45, 46, 47]. The fact that voltage-gated calcium channels only open at a certain voltage creates a threshold effect. In addition, calcium extrusion rates and buffering rates differ from cell to cell. Also many GECIs have further non-linearities through a Hill coefficient that is as great as 3 [22]. Finally, action potentials generate little or no calcium influx in some cell types [20].

Calcium dynamics are also slow in contrast with voltage changes which blurs the relationship between the optical signal and spike rates except at very low rates [43, 48, 49]. Optical measurements from GECIs can be further confounded by the kinetics of the protein sensor [12, 50]. GECIs are also likely to miss hyperpolarizations in neurons with low rates of spontaneous spiking, whereas some GEVIs can be tuned to respond differentially to hyperpolarization or depolarization [17, 51].

ArcLight’s ability to report odor-evoked activity in single trials and Ace2N-4AA-mNeon ability to follow individual spikes in individual cortical neurons demonstrates that GEVIs can be a useful tool for in vivo measurements. That said, GEVIs and GECIs are complementary tools, where the appropriate use depends on whether the improved temporal resolution and membrane potential sensitivity of GEVIs is more important than the improved signal-to-noise ratio and calcium sensitivity of the GCaMPs.

Box 2. Reporting important characteristics for GEVIs.

A substantial list of characteristics determine the utility of a GEVI for monitoring brain activity. We discuss how well each of these characteristics are described in the literature and make suggestions about improving the description. Signal size (ΔF/F per 100 mv), kinetics (ms), and V1/2 of fluorescence vs voltage (for GEVIs with sigmoidal responses) are routinely reported. The characteristics below are often reported but usually only qualitatively.

Brightness

The brightness of an FP is the product of two factors, the extinction coefficient (ε) and the quantum yield (ϕ). Quantum yield is simply the fraction of absorbed photons that lead to emitted fluorescence, while the extinction coefficient describes how strongly the chromophore absorbs light. For example, the fluorescent protein Clover has an extinction coefficient of 111,000 M−1 cm−1 and quantum yield of 0.76 [56] making it one of the brightest fluorescent proteins. Brightness could be routinely reported.

Expression level

A measurement of the average total fluorescence of a cell is an indication of expression level. For comparison purposes, this measurement should be corrected for brightness. Because the measurement of fluorescence will depend on characteristics of the measuring apparatus, an absolute value of expression level will be difficult to determine. However, it would be easy to compare the expression level of a new GEVI with that of an already established GEVI.

Plasma membrane localization

All of the published images of GEVI expression have substantial intracellular expression. This intracellular expression will reduce the ΔF/F and the signal-to-noise ratio. Two different methods have been used to measure plasma membrane localization. First, Figure 3 of Baker et al [25] illustrates a measurement of plasma membrane expression using confocal microscopy. The GEVI fluorescence is compared to an externally added dye which binds to but does not cross the plasma membrane. Second, Bedbrook et al [57] used an extracellular tag in a SpyTag/SpyCatcher system to measure the plasma membrane localization of channelrhodopsin. This scheme might also work for GEVIs.

Signal-to-noise ratio

This critical GEVI characteristic is not easily absolutely quantified because of its dependence on the preparation and the measurement apparatus. But a comparison with a previously established GEVI would be relatively easy and very useful.

Steepness of fluorescence vs voltage

(for GEVIs with sigmoidal responses). This characteristic will determine how well a GEVI could distinguish between action potentials, excitatory synaptic potentials, and inhibitory synaptic potentials in a population signal. Fluorescence vs voltage curves are typically fit with the Boltzmann equation, Y = (A1 − A2) / (1 + e(V − V1/2)/ dx) + A2, where A1 is the minimum value, and A2 is the maximum value and dx is the slope (steepness) of the Boltzmann fit. The slope should be routinely reported.

In vivo characterization

In vivo measurement of these characteristics is clearly important. First, because the in vivo result may be different from the in vitro result and second, because in vivo characterization will inform scientists who are deciding which, if any, GEVI to use. In vivo measurement of some characteristics will be difficult because they require simultaneous fluorescence and patch clamp measurements. But comparisons of different GEVIs in the same preparation would be very useful.

Trends Box.

Recently developed genetically encoded voltage sensors (GEVIs) have larger and faster fluorescence signals.

The new GEVIs result in improved signal-to-noise ratios in in vivo measurements in the mammalian brain.

In some instances GEVI signals are substantially faster and more informative than measurements with genetically encoded calcium sensors (GECIs).

Outstanding Questions.

Some GEVIs in Table 1 have relatively large signals while others have relatively fast signals. A GEVI with a signal that was both large and fast would increase the quality and the kinds of measurement that were possible.

What is the mechanism responsible for the GEVI fluorescence change? The results presented in Figure 6 suggest that voltage affects the equilibrium between monomers and dimers of that GEVI. Will this conclusion be true of other mosaic GEVIs? Will this information lead to the development of better GEVIs?

Can red shifted GEVIs with large signals be developed? Red sensors would allow simultaneous recordings from two cells types. Red sensors also have the advantage of reduced scattering of red wavelengths by the brain.

Can GEVIs be targeted to different sub-cellular locations? Specific targeting would improve the signal-to-noise ratio and avoid some types of ambiguity in interpreting population measurements.

Acknowledgments

Supported by US NIH grants DC005259 and NS054270, grant number WCI 2009-003 from the National Research Foundation of Korea, a James Hudson Brown – Alexander Brown Coxe fellowship from Yale University, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award DC012981.

Glossary

- FP

a fluorescent protein (e.g. Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP))

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Transfer of energy from one FP to a second, neighboring, FP

- GEVI

genetically encoded voltage indicator

- GECI

genetically encoded calcium indicator

- S1–S4

numbering of transmembrane helices in the voltage sensitive domain of the Ciona phosphatase

- super ecliptic pHluorin

A pH sensitive variation of GFP

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sherrington Sc. Man on His Nature. Cambridge University Press; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong Y, Wagner MJ, Zhong Li J, Schnitzer MJ. Imaging neural spiking in brain tissue using FRET-opsin protein voltage sensors. Nature communications. 2014;5:3674. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akemann W, Mutoh H, Perron A, Rossier J, Knöpfel T. Imaging brain electric signals with genetically targeted voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins. Nature Methods. 2010;7:643–649. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong Y, Huang C, Li JZ, Grewe BF, Zhang Y, Eismann S, Schnitzer MJ. High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. Science (New York, NY ) 2015;350:1361–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao G, Platisa J, Pieribone VA, Raccuglia D, Kunst M, Nitabach MN. Genetically targeted optical electrophysiology in intact neural circuits. Cell. 2013;154:904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flytzanis NC, Bedbrook CN, Chiu H, Engqvist MK, Xiao C, Chan KY, … Gradinaru V. Archaerhodopsin variants with enhanced voltage-sensitive fluorescence in mammalian and Caenorhabditis elegans neurons. Nature communications. 2014;5:4894. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunst M, Hughes ME, Raccuglia D, Felix M, Li M, Barnett G, … Nitabach MN. Calcitonin gene-related peptide neurons mediate sleep-specific circadian output in Drosophila. Current biology : CB. 2014;24:2652–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein M, Afonso B, Vonner AJ, Hernandez-Nunez L, Berck M, Tabone CJ, … Samuel AD. Sensory determinants of behavioral dynamics in Drosophila thermotaxis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E220–229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416212112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akemann W, Sasaki M, Mutoh H, Imamura T, Honkura N, Knopfel T. Two-photon voltage imaging using a genetically encoded voltage indicator. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2231. doi: 10.1038/srep02231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsutsui H, Jinno Y, Tomita A, Niino Y, Yamada Y, Mikoshiba K, … Okamura Y. Improved detection of electrical activity with a voltage probe based on a voltage-sensing phosphatase. J Physiol. 2013;591:4427–4437. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishina Y, Mutoh H, Song C, Knopfel T. Exploration of genetically encoded voltage indicators based on a chimeric voltage sensing domain. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2014;7:78. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storace DA, Braubach OR, Jin L, Cohen LB, Sung U. Monitoring brain activity with protein voltage and calcium sensors. Scientific reports. 2015;5:10212. doi: 10.1038/srep10212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St-Pierre F, Chavarha M, Lin MZ. Designs and sensing mechanisms of genetically encoded fluorescent voltage indicators. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2015;27:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storace D, Rad MS, Han Z, Jin L, Cohen LB, Hughes T, … Sung U. Genetically Encoded Protein Sensors of Membrane Potential. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2015;859:493–509. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17641-3_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knopfel T, Gallero-Salas Y, Song C. Genetically encoded voltage indicators for large scale cortical imaging come of age. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2015;27:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimitrov D, He Y, Mutoh H, Baker BJ, Cohen L, Akemann W, Knopfel T. Engineering and characterization of an enhanced fluorescent protein voltage sensor. PLoS One. 2007;2:e440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piao HH, Rajakumar D, Kang BE, Kim EH, Baker BJ. Combinatorial mutagenesis of the voltage-sensing domain enables the optical resolution of action potentials firing at 60 Hz by a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor of membrane potential. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:372–385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stosiek C, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K, Konnerth A. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charpak S, Mertz J, Beaurepaire E, Moreaux L, Delaney K. Odor-evoked calcium signals in dendrites of rat mitral cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:1230–1234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021422798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmchen F, Svoboda K, Denk W, Tank DW. In vivo dendritic calcium dynamics in deep-layer cortical pyramidal neurons. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2:989–996. doi: 10.1038/14788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peron S, Chen TW, Svoboda K. Comprehensive imaging of cortical networks. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2015;32:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose T, Goltstein PM, Portugues R, Griesbeck O. Putting a finishing touch on GECIs. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2014;7:88. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross WN. Understanding calcium waves and sparks in central neurons. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2012;13:157–168. doi: 10.1038/nrn3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel MS, Isacoff EY. A genetically encoded optical probe of membrane voltage. Neuron. 1997;19:735–741. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker BJ, Lee H, Pieribone VA, Cohen LB, Isacoff EY, Knopfel T, Kosmidis EK. Three fluorescent protein voltage sensors exhibit low plasma membrane expression in mammalian cells. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2007;161:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 2005;435:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin L, Han Z, Platisa J, Wooltorton JR, Cohen LB, Pieribone VA. Single action potentials and subthreshold electrical events imaged in neurons with a fluorescent protein voltage probe. Neuron. 2012;75:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akemann W, Mutoh H, Perron A, Park YK, Iwamoto Y, Knopfel T. Imaging neural circuit dynamics with a voltage-sensitive fluorescent protein. Journal of neurophysiology. 2012;108:2323–2337. doi: 10.1152/jn.00452.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St-Pierre F, Marshall JD, Yang Y, Gong Y, Schnitzer MJ, Lin MZ. High-fidelity optical reporting of neuronal electrical activity with an ultrafast fluorescent voltage sensor. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:884–889. doi: 10.1038/nn.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Junge W, Witt HT. On the ion transport system of photosynthesis--investigations on a molecular level. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung. Teil B: Chemie, Biochemie, Biophysik, Biologie. 1968;23:244–254. doi: 10.1515/znb-1968-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kralj JM, Douglass AD, Hochbaum DR, Maclaurin D, Cohen AE. Optical recording of action potentials in mammalian neurons using a microbial rhodopsin. Nat Methods. 2012;9:90–95. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Zhang Z, Chanda B, Jackson MB. Improved probes for hybrid voltage sensor imaging. Biophys J. 2010;99:2355–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perron A, Mutoh H, Akemann W, Gautam SG, Dimitrov D, Iwamoto Y, TK Second and third generation voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins for monitoring membrane potential. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2009;2 doi: 10.3389/neuro.3302.3005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung U, Sepehri-Rad M, Piao HH, Jin L, Hughes T, Cohen LB, Baker BJ. Developing Fast Fluorescent Protein Voltage Sensors by Optimizing FRET Interactions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilt BA, Fitzgerald JE, Schnitzer MJ. Photon shot noise limits on optical detection of neuronal spikes and estimation of spike timing. Biophys J. 2013;104:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Piao H, Sepheri Rad M, Jung A, Sung U, Song YK, Baker BJ. Imaging membrane potential with two types of genetically encoded fluorescent voltage sensors. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2015 doi: 10.3791/53566. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutoh H, Perron A, Dimitrov D, Iwamoto Y, Akemann W, Chudakov DM, Knopfel T. Spectrally-resolved response properties of the three most advanced FRET based fluorescent protein voltage probes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochbaum DR, Zhao Y, Farhi SL, Klapoetke N, Werley CA, Kapoor V, … Cohen AE. All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat Methods. 2014;11:825–833. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinberg D, Koulakov A, Gelperin A. Sparse odor coding in awake behaving mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0884-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carandini M, Shimaoka D, Rossi LF, Sato TK, Benucci A, Knopfel T. Imaging the awake visual cortex with a genetically encoded voltage indicator. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:53–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0594-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaffe DB, Johnston D, Lasser-Ross N, Lisman JE, Miyakawa H, Ross WN. The spread of Na+ spikes determines the pattern of dendritic Ca2+ entry into hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1992;357:244–246. doi: 10.1038/357244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Callaway JC, Ross WN. Frequency-dependent propagation of sodium action potentials in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of neurophysiology. 1995;74:1395–1403. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiller J, Major G, Koester HJ, Schiller Y. NMDA spikes in basal dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 2000;404:285–289. doi: 10.1038/35005094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emptage N, Bliss TV, Fine A. Single synaptic events evoke NMDA receptor-mediated release of calcium from internal stores in hippocampal dendritic spines. Neuron. 1999;22:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garaschuk O, Yaari Y, Konnerth A. Release and sequestration of calcium by ryanodine-sensitive stores in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 1):13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pozzo Miller LD, Petrozzino JJ, Golarai G, Connor JA. Ca2+ release from intracellular stores induced by afferent stimulation of CA3 pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slices. Journal of neurophysiology. 1996;76:554–562. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markram H, Helm PJ, Sakmann B. Dendritic calcium transients evoked by single back-propagating action potentials in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1995;485(Pt 1):1–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Svoboda K, Denk W, Kleinfeld D, Tank DW. In vivo dendritic calcium dynamics in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;385:161–165. doi: 10.1038/385161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wachowiak M, Economo MN, Diaz-Quesada M, Brunert D, Wesson DW, White JA, Rothermel M. Optical dissection of odor information processing in vivo using GCaMPs expressed in specified cell types of the olfactory bulb. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:5285–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4824-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung A, Garcia JE, Kim E, Yoon BJ, Baker BJ. Linker length and fusion site composition improve the optical signal of genetically encoded fluorescent voltage sensors. Neurophotonics. 2015;2:021012. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.2.2.021012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnett L, Platisa J, Popovic M, Pieribone VA, Hughes T. A fluorescent, genetically-encoded voltage probe capable of resolving action potentials. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han Z, Jin L, Chen F, Loturco JJ, Cohen LB, Bondar A, … Pieribone VA. Mechanistic studies of the genetically encoded fluorescent protein voltage probe ArcLight. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang B, Baker BJ. Pado, a fluorescent protein that resolves pH and membrane potential changes reveals insights into the voltage-dependent, optical signal. 2015 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science (New York, NY ) 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lam AJ, St-Pierre F, Gong Y, Marshall JD, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, … Lin MZ. Improving FRET dynamic range with bright green and red fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1005–1012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bedbrook CN, Kato M, Ravindra Kumar S, Lakshmanan A, Nath RD, Sun F, … Gradinaru V. Genetically Encoded Spy Peptide Fusion System to Detect Plasma Membrane-Localized Proteins In Vivo. Chemistry & biology. 2015;22:1108–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sung U, Sepehri Rad M, Jin L, Hughes T, Cohen LB, Baker BJ. Improving signal dynamics of fluorescent protein voltage sensors by optimizing FRET interactions. PLoS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141585. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang B, Baker BJ. Monomeric fluorescent proteins reduce the optical signal of genetically encoded voltage indicators. 2015 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treger JS, Priest MF, Bezanilla F. Single-molecule fluorimetry and gating currents inspire an improved optical voltage indicator. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.10482. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang D, McMahon S, Zhang Z, Jackson MB. Hybrid voltage sensor imaging of electrical activity from neurons in hippocampal slices from transgenic mice. Journal of neurophysiology. 2012;108:3147–3160. doi: 10.1152/jn.00722.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zou P, Zhao Y, Douglass AD, Hochbaum DR, Brinks D, Werley CA, … Cohen AE. Bright and fast multicoloured voltage reporters via electrochromic FRET. Nature communications. 2014;5:4625. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]