Abstract

Objective

To investigate antecedents of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms in children born extremely preterm (EP; <26 weeks gestation).

Method

The EPICure Study recruited all babies born EP in the UK and Ireland in March-December 1995. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed at 2.5 (n=283; 90%), 6 (n=160; 78%) and 11 (n=219; 71%) years of age. Parents and teachers completed the Du Paul Rating Scale-IV to assess inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms at 11 years. Regression analyses were used to explore the association of neonatal, neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes to 6 years with ADHD symptoms at 11 years.

Results

EP children had significantly more inattention (mean difference 1.2 SD; 95% CI 0.9, 1.5) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.5 SD; 0.2, 0.7) than controls, with a significantly greater effect size for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity. Significant independent predictors of inattention at 11 years included smaller head circumference, lower IQ and pervasive peer relationship problems at 6 years, and motor development at 2.5 years. In contrast, significant independent predictors of hyperactivity/impulsivity included lower IQ, pervasive conduct problems and ADHD symptoms at 6 years, externalizing problems at 2.5 years and non-white maternal ethnicity.

Conclusions

EP children are at increased risk for ADHD symptoms, predominantly inattention, for which the antecedents differ by symptom domain. Attention deficits following EP birth were associated with poor brain growth and neurological function. Cognitive and behavioral assessments in early and middle childhood to identify neurodevelopmental and peer relationship problems may be beneficial for identifying EP children at risk for inattention.

Keywords: Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Preterm, inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, neurodevelopment, peer relationship problems

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a pervasive neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that emerge early in childhood and interfere with an individual’s social, academic and occupational functioning.1 ADHD is classified into three diagnostic sub-types comprising ADHD Combined (ADHD/C) in which clinically significant levels of both hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention are present, ADHD Predominantly Inattentive (ADHD/I) in which only a clinically significant level of inattention is present, and ADHD Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive (ADHD/H) in which a only clinically significant level of hyperactivity/impulsivity is present.

A growing number of studies demonstrate that extremely low birthweight (<1000g) or extremely preterm (EP; <26 weeks gestation) birth is associated with 3 to 4 times increased risk for psychiatric disorders in middle childhood2, of which the most prevalent is ADHD. In population-based studies of EP/ELBW cohorts born in the 1990s, prevalence estimates for ADHD range from 10% to 17%3-5 in middle childhood, representing a four fold increase in the odds of a diagnosis compared with children born at term.6 A two to three fold increase in the risk for ADHD has also been observed in kindergarten children born <1000g/<28 weeks gestation compared with their term-born peers.7

Additionally, the preterm ADHD phenotypic profile appears to differ from that typically observed in children with ADHD in the general population.8 Following EP birth, ADHD is associated with a greater risk for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity in terms of both symptoms4, 9-16 and sub-type disorders.5, 14 In some studies, the increased risk for ADHD diagnoses has been found to be specific to ADHD/I alone.4, 5, 14 There are also phenotypic differences in the patterns of comorbidity, in which there is a notable absence of comorbid conduct disorders in preterm children with ADHD8, contrasting with the frequent co-occurrence of ADHD and conduct disorders in children in the general population.17 Furthermore, the greater risk for ADHD in males is frequently not observed in preterm samples.8

To date, few studies have investigated the presentation of ADHD symptoms in EP children and none have explored both neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological predictors of ADHD symptoms along separate dimensions. Exploring the mechanisms that underlie the preterm phenotype from the earliest points in development is important for understanding the etiology of ADHD symptoms and for developing and targeting interventions in this population. Here we report the results of a national population-based study of outcomes following EP birth. The aims of the present report were to investigate the prevalence and antecedents of ADHD symptoms in EP children at 11 years of age and to determine whether these antecedents differed by symptom domain. We hypothesized that EP children would have significantly higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity than term born controls and that there would be a significantly greater risk for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity in EP children. We also hypothesized that early indices of biological and neurodevelopmental risk would more strongly associated with the development of symptoms of inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity at 11 years of age.

METHOD

Participants

All babies born at 25 completed weeks of gestation or less from 1st March through 31st December 1995 who were admitted for neonatal intensive care across the whole of the UK and Ireland were identified as part of the EPICure Study (n=811). There were no exclusion criteria and all births admitted to intensive care during the study period were identified. All surviving children were invited to participate in follow-up assessments, for which 283 (90% of survivors) were assessed at two years of age18, 241 (78% of survivors) at six years of age19 and 219 (71% of survivors) at 11 years of age.20 The present report focuses on the exploration of antecedents of ADHD symptoms assessed at 11years.

At the 6-year assessment, a term-born control group of 160 children born ≥37 weeks gestation was randomly selected from age-, ethnicity- and sex-matched classmates for EP children in mainstream schools. These children were invited to participate again in the 11-year outcome evaluation, at which time 110 children were-reassessed. At this time an additional 43 controls were recruited for EP children who did not have a matched control at the 6-year assessment or for those whose original matched 6-year control attended a different school. Thus a total of 153 term-born controls were assessed at 11 years of age (see20 for a detailed description of the EPICure cohort).

Procedure

At two years of age, EP children were assessed in an outpatient clinic by a pediatrician. At both six and 11 years of age, EP children and their controls were assessed at school or at home by a pediatrician and a psychologist who were blind to the child’s clinical history and study group allocation. The 11-year study was approved by the Southampton and South West Hampshire NHS Research Ethics Committee (Ref 05/Q1702/126).

Neonatal Data (EP Children Only)

Information about EP children’s obstetric and neonatal course was obtained at discharge from hospital. Variables included maternal age, gestational age, birthweight, head circumference, multiple birth, mother’s ethnic origin, use of antenatal steroids, preterm premature rupture of membranes, method of delivery, fetal heart rate at 5 min, temperature, Clinical Risk Index for Babies (CRIB) score, chorioamnionitis (suspected or proven), abnormal cranial ultrasound scan (defined as large parenchymal cysts or ventriculomegaly), evidence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), use of postnatal steroids for chronic lung disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD; supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks post menstrual age), receipt of any breast milk and duration of NICU admission.

Outcome Measures at Two Years of Age (EP Children Only)

At two years of age, the Mental Development Index (MDI) and the Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID-II)21 were used to assess cognitive and motor development from which standardized scores (Mean 100; SD 15) were derived. Serious cognitive impairment was classified using scores < −2 SD of the standardization sample (MDI/PDI scores <70). MDI scores were combined with the results of a clinical evaluation to identify children with serious functional disability defined as one or more of moderate/severe cognitive, vision (blind or severely impaired vision not corrected by aids), hearing (deaf or hearing loss requiring aids) or gross motor impairment (non-ambulant cerebral palsy). Neurodevelopmental outcomes at two years of age have been published previously.18 A head circumference standard deviation score (SDS; Mean 0, SD 1) was also computed using the 1990 British Growth Standards for age and sex. Parent-reports of behavior problems at two years were also obtained using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)22 from which standardized T-scores (Mean 50; SD 10) were derived for internalizing and externalizing behavior problems with higher scores indicating greater problems. Parents’ self-reports of their smoking in pregnancy were obtained and self-reports of their occupation were used to classify their occupational status into three categories: non-manual, manual and unemployed.

Outcome Measures at Six Years of Age (EP Children and Controls)

At six years of age, the NEPSY Developmental Neuropsychological Test23 was used to assess neuropsychological skills. From this test three global scales were selected in order to provide an assessment of the cognitive domains most compromised by EP birth and previously shown to be associated with academic and behavioral difficulties in this population, namely (1) visuospatial processing (visuo-motor integration and judgement of line orientation); (2) sensorimotor skills (manual dexterity and fine motor skills); and (3) Attention/Executive Function (planning and monitoring, selective attention and inhibition and motor persistence). Standardized scores (Mean 100; SD 15) were derived for each of these three core domains. Data relating to children’s performance on these measures has been published previously.24 Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed using a battery of clinical and psychometric tests. Children’s general cognitive ability (IQ) was assessed using the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (K-ABC)25 from which a standardized Mental Processing Composite (MPC) score was derived (Mean 100; SD 15). Children who could not be assessed due to severe disability were assigned a nominal score of 39 (1-point below the lowest test score) to quantify IQ in the severely impaired range. Moderate/severe cognitive impairment was classified using the conventional SD banded definition of scores < −2 SD. However, as the well-documented ‘Flynn effect’ results in an upward drift of standardised test scores over time26, the test scores of contemporary populations may be higher than published norms and the prevalence of impairment may be underestimated where obsolete tests are applied.27 Thus it is recommended that contemporaneous reference groups are used to classify abnormality where possible.27 As the K-ABC was standardised in the 1970s, we used the Mean (SD) of the contemporaneous control group to classify cognitive impairment (i.e., MPC < 82). A clinical evaluation was also performed from which moderate to severe impairment in vision, hearing and gross motor function was classified for each child using the definitions provided above. These classifications were combined with MPC scores to identify children with serious neurodevelopmental disability defined as one or more of cognitive, vision, hearing or motor impairment. Neurodevelopmental outcomes for this cohort have been published in detail previously.19 Head circumference was also measured from which a SDS for age and sex was calculated using the 1990 British Growth Standards. In addition, behavioural, social and emotional problems were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)28 completed by each child’s parent and main class teacher. From these questionnaires, scores >90th percentile of the term control group were used to identify children with clinically significant emotional problems, conduct problems, inattention/hyperactivity and peer relationship problems. Congruence between parent and teacher reports of clinically significant difficulties was used to identify children with pervasive problems in each domain as these have been shown to have good diagnostic utility for childhood psychiatric disorders.29 Data relating to behavioral, social and emotional outcomes at six years of age have been reported previously.13

Outcome Measures at Eleven Years of Age (EP Children and Controls)

The primary outcome for this study was ADHD symptoms assessed using the Du Paul ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD RS-IV)30 completed by parents and teachers. This 18-item questionnaire, based on the diagnostic criteria for ADHD as described in DSM-IV31, comprises two sub-scales to assess Inattention (nine items) and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (nine items) symptoms. Three summary scores were derived for Inattention, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Total ADHD symptoms. For all scales, higher scores indicated a greater frequency of symptoms. To enable direct comparison of scores across scales, standard deviation scores (SDS; Mean 0, SD 1) were calculated for the three summary scores using age- and sex-specific control data as the reference. Similarly, a SDS of the mean of the parent and teacher scores was also computed for each child to provide aggregated multi-informant data recommended for assessing childhood psychopathology, particularly ADHD.29, 32 The ADHD RS-IV is widely used for clinical and research purposes and has good psychometric properties; the sub-scales have high levels of internal consistency and test-retest reliability30 and the scale has good discriminative validity for differentiating children with ADHD/I from children with ADHD/C sub-type disorders.33 At 11 years of age, a clinical evaluation was also performed from which impairment in vision, hearing and motor function was classified for each child. These classifications were combined with concurrent IQ (MPC) scores to identify children with mild, moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability using standard definitions. These data have been published previously.20 Highest parental occupation was classified into four categories (I: professional/managerial; II: intermediate; III routine /manual; IV: long-term unemployed/never worked) using the UK National Statistics socio-economic classification system.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using STATA 10.34 All growth SDS were calculated in STATA using the 1990 British Growth Standards for age and sex. Differences in ADHD-RS-IV scores between EP children and term-born controls were analysed using linear regression with results presented as differences in means with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation was used to estimate the effect on inattention symptoms in the whole population of EP children alive at 11 years of age. Additionally, in children with IQ in the average range (MPC ≥90) and for subgroups of children with differing severity of neurodevelopmental disability at 11 years of age, differences in ADHD symptoms between EP children and controls were explored using multivariable linear regression to adjust for IQ (MPC at 11 years of age).

To explore antecedents of ADHD symptoms in EP children, variables were established a priori as potential predictors because of their documented association with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, and their univariable associations with ADHD symptoms were tested. Multivariate analysis was then used to test whether each predictor variable had significantly different associations with the combined parent and teacher inattention SDS versus combined parent and teacher hyperactivity/impulsivity SDS.

Multiple linear regression was then used to identify significant independent predictors separately for inattention and for hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms in EP children at 11 years of age. All P values are 2-sided and statistical significance is p<0.05.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Questionnaire response rates and the characteristics of children assessed at 11 years of age are shown in Table 1. ADHD-RS-IV questionnaires were completed by up to 92% of parents and up to 95% of class teachers. Both parent and teacher questionnaires were received for 172 (79%) EP children and 134 (88%) controls. There were no significant differences in age and sex between EP children and controls, however parents of EP children had significantly lower occupational status compared with parents of controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of extremely preterm children and tern-born controls assessed at 11 years of age.

| All children | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Term controls (n=153) | EP children (n=219) | ||

| ADHD RS-IV completed | |||

| Parent | n (%) | 140 (92) | 189 (86) |

| Teacher | n (%) | 146 (95) | 197 (90) |

| Parent & teacher | n (%) | 134 (88) | 172 (79) |

| Neither | n (%) | 1 (1) | 5 (2) |

|

| |||

| Children with parent & teacher data | |||

| Term controls (n=134) | EP children (n=172) | ||

|

| |||

| Age in months | Mean (SD) | 131 (6.7) | 130 (4.3) |

| Male | n (%) | 56 (42) | 77 (45) |

| Parent occupational status* | |||

| 1 (highest) | n (%) | 73 (57) | 70 (43) |

| 2 | n (%) | 20 (16) | 40 (24) |

| 3 | n (%) | 32 (25) | 44 (27) |

| 4 (lowest) | n (%) | 3 (2) | 9 (6) |

| Data at 2 years | n (%) | n/a | 169 (98) |

| Data at 6 years | n (%) | 96 (72) | 160 (93) |

| Neurodevelopmental outcomes | |||

| Any neurodevelopmental impairment | 2 (1.5%) | 69 (40.1%) | |

| Vision impairment | 0 | 12 (7%) | |

| Hearing impairment | 0 | 3 (1.7%) | |

| Gross motor impairment | 0 | 11 (6.4%) | |

| Cognitive impairment | 2 (1.5%) | 59 (34%) | |

Controls n=128, EP n=163; p=0.04.

A dropout analysis of EP survivors not assessed at 11 years and those with incomplete data (n=135) versus those with complete data (n=172) was conducted. This revealed that dropouts were significantly more likely to have parents of lower occupational status, non-white maternal ethnic origin, to have had NEC during the neonatal period or to have had a diagnosis of cerebral palsy or serious neurodevelopmental disability at two years of age.

ADHD Symptoms at Eleven Years of Age

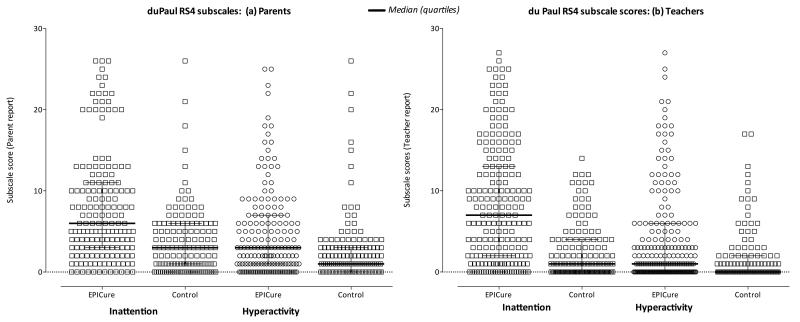

The distribution of parent and teacher rated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores for EP children and controls is shown in Figure 1. Between-group differences in mean scores are shown in Table 2. Amongst all children assessed at eleven years, parents and teachers both rated EP children with significantly greater symptoms of inattention (Mean difference scores on parent ratings: 1.3 SD, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.6; Mean difference scores on teacher ratings: 1.0 SD, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.2) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Mean difference scores on parent ratings: 0.7 SD, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9; Mean difference scores on teacher ratings: 0.4 SD, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.6) than term-born controls. For both parents and teachers, the effect size was consistently greater for inattention (parent 1.3 SD; teacher 1.0 SD) than hyperactivity/impulsivity (parent 0.7 SD; teacher 0.40 SD). Among EP children, both parent and teacher rated inattention scores were significantly higher than hyperactivity/impulsivity scores (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of parent (Figure 1a) and teacher (Figure 1b) total scores for symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity at 11 years of age in extremely preterm children (EPICure) and term-born controls. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms. Bars indicate group mean and SD.

Table 2.

ADHD symptoms in extremely preterm (EP; < 26 weeks gestation) children and term-born (≥37 weeks gestation) controls at 11 years of age assessed using the Du Paul ADHD Rating Scale-IV.

| All children | ||||

|

| ||||

| Term | EP | Difference in means | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Raw score (95% CI) | SD score# (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Parent Scores | n=140 | n=189 | ||

| Inattention | 3.6 (4.1) | 8.8 (6.9) | 5.1 (3.8 to 6.4)*** | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.6)*** |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.6 (4.1) | 5.3 (5.5) | 2.7 (1.6 to 3.8)*** | 0.7 (0.4 to 0.9)*** |

|

| ||||

| Teacher Scores | n=146 | n=197 | ||

| Inattention | 3.3 (4.9) | 7.9 (7.1) | 4.6 (3.3 to 6.0)*** | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.2)*** |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.1 (4.2) | 3.7 (5.4) | 1.6 (0.6 to 2.7)** | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.6)** |

|

| ||||

| Children with both parent & teacher data | ||||

|

| ||||

| Term | EP | Difference in means | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Raw score (95% CI) | SD score# (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Parent Scores | n=134 | n=172 | ||

| Inattention | 3.7 (4.2) | 8.7 (6.7) | 5.0 (3.7 to 6.3)*** | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5)*** |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.6 (4.2) | 5.2 (5.4) | 2.6 (1.5 to 3.7)*** | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9)*** |

|

| ||||

| Teacher Scores | n=134 | n=172 | ||

| Inattention | 3.0 (4.6) | 7.0 (6.5) | 3.9 (2.6 to 5.3)*** | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1)*** |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.1 (4.3) | 2.9 (4.4) | 0.8 (−0.2 to 1.8) | 0.2 (−0.0 to 0.4) |

|

| ||||

| Mean of parent & teacher | n=134 | n=172 | ||

| Inattention | 3.3 (4.9) | 7.9 (7.1) | 4.5 (3.3 to 5.6)*** | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5)*** |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.1 (4.2) | 3.7 (5.4) | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.7)** | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.7)** |

|

| ||||

| Mean of parent & teacher in children with MPC ≥90 at 11 years $ | n=124 | n=74 | ||

|

| ||||

| Inattention | 3.1 (3.7) | 5.4 (5.3) | 1.5 (0.24 to 2.8)* | 0.42 (0.10 to 0.75)* |

|

| ||||

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.2 (3.5) | 2.7 (3.6) | 0.1 (−0.9 to 1.2) | 0.05 (−0.23 to 0.33) |

Higher scores indicate greater ADHD symptoms.

SD Standard Deviation score using the term-born controls as the reference (term control group mean = 0; SD = 1).

Adjusted for MPC at 11 years.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

When children with both parent and teacher data were considered (EP n=172; Control n=134), parents rated EP children with significantly higher inattention (mean difference: 1.2 SD, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.5) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (mean difference: 0.6 SD, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9) than controls, with a greater effect size for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity. In contrast, teachers rated EP children with significantly higher inattention (mean difference: 0.8 SD, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.1) but not hyperactivity/impulsivity (mean difference: 0.2 SD, 95% CI −0.0 to 0.4) than controls (Table 2). Inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores were highly correlated in both groups (EP children r=0.72; Control r=0.80; p <0.001) and analysis of the mean of the parent and teacher SDS produced the same pattern of results with significant between-group differences in both symptom domains and a significantly greater effect size for inattention (mean difference 1.2 SD; 95% CI 0.9 to 1.5) compared to that for hyperactivity/impulsivity (mean difference 0.5 SD; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7) (Table 2). Using multiple imputation to estimate the effect on outcomes in the whole population of EP children alive at 11 years of age, the mean difference in inattention was 1.3 SD (95% CI 1.06 to 1.49).

ADHD symptom scores by severity of neurodevelopmental disability at 11 years of age are shown in Table 3. The differences are consistent with the results by group overall, with no significant differences between EP children and controls in hyperactivity/impulsivity in any disability subgroup. For those with no or mild disabilities, EP children had significantly higher inattention scores than controls. Adjustment for IQ attenuated this effect but with a significant difference remaining between EP children and controls with no disabilities. In the combined mild and no disabilities subgroup, the difference in inattention after adjustment for IQ remained statistically significant at 0.43 SD (0.12 to 0.74). This effect was unaltered when also adjusting for parental occupational status at 11 years.

Table 3.

Du Paul ADHD Rating Scale-IV SD scores in extremely preterm (EP; < 26 weeks gestation) children and term-born (≥37 weeks gestation) controls at 11 years of age by neurodevelopmental disability subgroup.

| Neurodevelopmental disability at 11 years* (number EP : Term) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| (30 : 97) | (73 : 35) | (50 : 2) | (19 : 0) | |

| Mean (SD) Inattention SD score | ||||

| EP | 0.47 (1.4) | 0.83 (1.3) | 1.69 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.5) |

| Term | −0.11 (0.9) | 0.23 (1.1) | 1.23 (0.2) | - |

| EP vs. Term | ||||

| Mean difference (95% CI) | 0.58 (0.13 to 1.02) | 0.61 (0.11 to 1.11) | 0.46 (−0.17 to 2.6) | - |

| Adjusted for IQ | 0.50 (0.05 to 0.95) | 0.38 (−0.11 to 0.85) | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) Hyperactivity/Impulsivity SD score | ||||

| EP | −0.05 (0.8) | 0.27 (0.9) | 0.69 (1.1) | 1.25 (1.2) |

| Term | −0.06 (0.9) | 0.13 (1.2) | 0.54 (1.4) | - |

| EP vs. Term | ||||

| Mean difference (95% CI) | 0.00 (−0.37 to 0.38) | 0.14 (−0.27 to 0.54) | 0.15 (−1.5 to 1.8) | - |

| Adjusted for IQ | −0.14 (−0.03 to 0.004) | 0.02 (−0.04 to −0.003) | - | - |

Neurodevelopmental disability was classified using the child’s most severe level of impairment in any one or more of vision, motor, hearing or cognitive function. Detailed definitions have been published previously.20

Antecedents of ADHD Symptoms in EP Children: Univariable Analyses

The association of combined parent and teacher ADHD-RS-IV SDS with all neonatal, two-year and six-year variables detailed in the methods was explored. Table 4 shows those variables that were significantly associated on univariable analyses and whether these differed by symptom domain.

Table 4.

Significant univariable associations with combined parent and teacher ADHD-RS-IV SD scores in extremely preterm children at 11 years of age.

| Inattention SD Score (A) | Hyperactivity/Impulsivity SD Score (B) | Significance of different effect of predictor variable on (A) and (B) 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | p-value | |

| Neonatal Variables | |||||

| Male sex | 0.41 (−0.04 to 0.86) | 0.07 | 0.33 (0.01 to 0.64) | 0.04 | 0.66 |

| Not received any breast milk by discharge | 0.84 (0.19 to 1.48) | 0.012 | 0.69 (0.24 to 1.15) | 0.003 | 0.47 |

|

| |||||

| Two year outcomes | |||||

| Parent occupational status (per category)2 | 0.24 (−0.04 to 0.53) | 0.09 | 0.22 (0.02 to 0.42) | 0.032 | 0.79 |

| Cognitive impairment3 | 1.12 (0.47 to 1.77) | 0.001 | 0.50 (0.03 to 0.96) | 0.037 | 0.01 |

| BSID-II Mental Development Index (per 10 points) | −0.38 (−0.54 to 0.22) | <0.001 | −0.19 (−0.30 to −0.07) | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| BSID-II Psychomotor Development Index (per 10 points) | −0.39(−0.54 to −0.25) | <0.001 | −0.19 (−0.29 to −0.08) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serious functional disability | 0.52 (0.23 to 0.81) | 0.001 | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.51) | 0.005 | 0.03 |

| Head circumference (per SDS) | −0.37 (−0.53 to −0.20) | <0.001 | −0.22 (−0.33 to −0.10) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| CBCL Internalising behaviour problems (per 10 points)4 | 0.38 (0.17 to 0.58) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.08 to 0.38) | 0.003 | 0.06 |

| CBCL Externalising behaviour problems (per 10 points) 4 | 0.38 (0.16 to 0.60) | 0.001 | 0.32 (0.16 to 0.48) | <0.001 | 0.48 |

|

| |||||

| Six year outcomes | |||||

| Cognitive impairment5 | 1.16 (0.70 to 1.62) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.27 to 0.96) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Mental Processing Composite score (per 10 points) | −0.35 (−0.48 to −0.23) | <0.001 | −0.21 (−0.30 to −0.12) | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Serious functional disability | 1.06 (0.61 to 1.50) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.10 to 0.78) | 0.011 | <0.001 |

| Head circumference (per SDS) | −0.27 (−0.40 to −0.13) | <0.001 | −0.14 (−0.23 to −0.04) | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| SDQ Pervasive conduct problems6 | 2.02 (1.04 to 3.00) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.00 to 2.40) | 0.003 | 0.39 |

| SDQ Pervasive hyperactivity problems6 | 1.18 (0.60 to 1.76) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.58 to 1.43) | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| SDQ Pervasive peer relationship problems6 | 1.63 (1.00 to 2.26) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.26 to 1.24) | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| NEPSY Sensorimotor skills (per 10 points)7 | −0.34 (−0.47 to −0.20) | <0.001 | −0.19 (−0.28 to −0.09) | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| NEPSY Visuospatial processing (per 10 points) 7 | −0.40 (−0.54 to −0.25) | <0.001 | −0.20 (−0.32 to −0.09) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NEPSY Attention/Executive function (per 10 points) 7 | −0.27 (−0.42 to −0.12) | 0.001 | −0.15 (−0.26 to −0.04) | 0.004 | 0.03 |

Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

P value <0.05 indicates that the coefficient for the inattention SD score is significantly different from that of the hyperactivity/impulsivity SD score with results derived from a multivariate analysis of the two SD scores as dependent variables with the single predictor variable.

Parent occupational status in 3 categories: (1) Non-manual, (2) manual and (3) never worked.

Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition, Mental Development Index (MDI) score −2 SD (scores <70).

Child Behavior Checklist T Score (Mean 50; SD 10).

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, Mental, Processing Composite (MPC/IQ) score −2 SD of classmates (scores <82).

SDQ Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; pervasive refers to congruence between parental and teacher categorisation of clinically significant problems (scores >90th percentile of term-born controls).

NEPSY refers to Developmental Neuropsychological Test core domain score (Mean 100; SD 15).

Note: The following variables were not significantly associated with either symptom score: gestational age; birth weight; birth weight SD score; head circumference at birth; multiple birth; non-white ethnic origin; antenatal steroids; preterm premature rupture of membranes; vaginal breech delivery; fetal heart rate >100bpm at 5 min; temperature <35C; CRIB- Clinical Risk Index for Babies score; chorioamnionitis; abnormal cranial ultrasound scan; necrotising enterocolitis; any postnatal steroids; bronchopulmonary dysplasia; duration of NICU admission; maternal age; maternal smoking in pregnancy and SDQ Pervasive emotional problems at six years.

Of birth characteristics and neonatal variables examined, not having received any breast milk by discharge was significantly associated with both higher inattention (0.84 SD, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.48) and higher hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.69 SD, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.15) symptoms and the effect did not differ significantly between symptom domains. Male sex was significantly associated with higher hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.33 SD, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.64) but not quite with inattention (0.41 SD, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.86) scores.

Of data collected at two years, higher scores for parent rated internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were significantly associated with inattention (internalizing: 0.38 SD, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.58; externalizing: 0.38 SD, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.60) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (internalizing: 0.23 SD, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.38; externalizing: 0.32 SD, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.48) at 11 years, but there was no significant difference in the strength of these associations between symptom domains. Lower parental occupational status at two years was significantly associated with hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.22 SD, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.42), but not quite with inattention (0.24 SD, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.53). Notably, cognitive impairment, lower MDI and PDI scores, functional disability and smaller head circumference were significantly associated with symptoms of both inattention (cognitive impairment: 1.12 SD, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.77; MDI score per 10 point increase: −0.38 SD, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.22; PDI score per 10 point increase: −0.39 SD, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.25; functional disability: 0.52 SD, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.81; OFC per SDS: −0.37 SD, 95% CI −0.53 to −0.20) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (cognitive impairment: 0.50 SD, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.96; MDI score per 10 point increase: −0.19 SD, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.07; PDI score per 10 point increase: −0.19 SD, 95% CI −0.29 to −0.08; functional disability: 0.30 SD, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.51; OFC per SDS: −0.22 SD, 95% CI −0.33 to −0.10) but, in each case, the effect size was significantly greater for inattention than for hyperactivity/impulsivity (Table 4).

Again, at six years of age, indices of poor neurodevelopmental function, namely cognitive impairment, functional disability, smaller head circumference and lower MPC scores, were significantly associated with inattention (cognitive impairment: 1.16 SD, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.62; functional disability: 1.06 SD, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.50; OFC per SDS: −0.27 SD, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.13); MPC per 10 points: −0.35 SD, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.23) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (cognitive impairment: 0.61 SD, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.96; functional disability: 0.44 SD, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.78; OFC per SDS: −0.14 SD, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.04); MPC per 10 points: −0.21 SD, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.12) at 11 years of age, and in each case the effect size was significantly greater for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity (Table 4).

A similar pattern of findings was observed for measures of neuropsychological abilities. Poorer performance on tests of sensorimotor skills, visuospatial processing and attention/executive function was associated with symptoms of both inattention (sensorimotor per 10 points: −0.34 SD, 95% CI −0.47 to −0.20; visuospatial per 10 points: −0.40 SD, 85% CI −0.54 to −0.25; attention/executive function per 10 points −0.27 SD, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.12) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (sensorimotor per 10 points: −0.19 SD, 95% CI −0.28 to −0.09; visuospatial per 10 points: −0.20 SD, 85% CI −0.32 to −0.09; attention/executive function per 10 points −0.15 SD, 95% CI −0.26 to −0.04). The associations of poorer performance with symptoms of inattention were significantly stronger than with hyperactivity/impulsivity in all three domains assessed (Table 4).

As noted above, the SDQ was used to identify children with pervasive problems in each domain, that is, where both the parent and teacher rated the child with clinically significant difficulties. Analysis of SDQ data revealed that pervasive conduct problems at 6 years were associated with higher inattention (2.02 SD, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.00) and hyperactivity/impulsivity 1.71 SD, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.40), and the strength of these associations did not differ between domains. Similarly, pervasive hyperactivity/inattention at 6 years was associated with inattention (1.18 SD, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.76) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (1.00 SD, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.43), and the strength of these associations did not differ between domains. However, whilst pervasive peer relationship difficulties on the SDQ were also associated with both higher inattention (1.63 SD, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.26) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.75 SD, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.24), the association was significantly stronger for inattention than for hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms.

Independent Predictors of ADHD Symptoms in EP children: Multivariable Analyses

As many of the predictor variables were highly correlated, multivariable linear regressions were used to identify significant independent predictors of ADHD symptoms in EP children using the combined parent and teacher ADHD-RS-IV scores for each domain. When all potential predictors were included in the model the following was observed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Variables significantly and independently associated with inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms in extremely preterm children at 11 years of age on multivariable regression analyses.

| Inattention SD Score | Hyperactivity/Impulsivity SD Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | |

| Factors arising by discharge from hospital | n=170; R2=8.0% | n=171; R2= 7.5% | ||

|

| ||||

| Transferred within 24 hours of birth | - | - | 0.50 (0.02 to 0.98) | 0.040 |

| Not having received any breast milk by discharge | 0.89 (0.25 to 1.52) | 0.007 | 0.57 (0.11 to 1.04) | 0.016 |

| Non-white maternal ethnicity | 0.58 (0.01 to 1.14) | 0.046 | - | - |

| Abnormal neonatal cranial ultrasound scan | 0.61 (0.01 to 1.22) | 0.047 | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Factors arising by the two year evaluation | n=154; R2=24.7% | n=165; R2=18.0% | ||

|

| ||||

| BSID-II PDI score (per 10 points)1 | −0.30 (−0.44 to −0.16) | <0.001 | - | - |

| Head circumference (per SDS) | −0.29 (−0.45 to −0.13) | <0.001 | −0.16 (−0.27 to −0.05) | 0.006 |

| CBCL Internalising behaviour problems (per 10 points)2 | 0.29 (0.01 to 0.50) | 0.006 | - | - |

| CBCL Externalising behaviour problems (per 10 points)3 | - | - | 0.28 (0.12 to 0.43) | 0.001 |

| Not having received any breast milk by discharge | - | - | 0.50 (0.07 to 0.93) | 0.023 |

| Abnormal neonatal cranial ultrasound scan | - | - | 0.48 (0.05 to 0.90) | 0.027 |

|

| ||||

| Factors arising by the six year evaluation | n=130; R2=41.1% | n=138; R2=31.1% | ||

|

| ||||

| Head circumference at 6 years (per SDS) | −0.30 (−0.46 to −0.13) | 0.001 | - | - |

| MPC at 6 years (per 10 points)3 | −0.18 (−0.33 to −0.03) | 0.021 | −0.11 (−0.20 to −0.01) | 0.025 |

| BSID-II PDI score at 2 years (per 10 points)1 | −0.20 (−0.36 to −0.05) | 0.010 | - | - |

| SDQ Pervasive peer relationship problems at 6 years4 | 1.01 (0.44 to 1.58) | 0.001 | - | - |

| SDQ Pervasive conduct problems at 6 years4 | 1.17 (0.22 to 2.1) | 0.016 | 1.22 (0.54 to 1.90) | 0.001 |

| SDQ Pervasive hyperactivity problems at 6 years4 | - | - | 0.54 (0.11 to 0.98) | 0.015 |

| CBCL Externalising behaviour problems at 2 years (per 10 points)2 | - | - | 0.22 (0.06 to 0.38) | 0.008 |

| Non-white maternal ethnicity | - | - | 0.50 (0.09 to 0.09) | 0.016 |

Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition, Psychomotor Development Index score (Mean 100; SD 15).

Child Behavior Checklist T-scores (Mean 50; SD 10).

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, Mental, Processing Composite score (Mean 100; SD 15).

SDQ Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; pervasive refers to congruence between parental and teacher categorisation of clinically significant problems (scores >90th percentile of term-born controls).

By discharge from hospital, not having received any breast milk was significantly associated with greater symptoms of both inattention (0.89 SD, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.52) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (0.57 SD, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.04), while non-white maternal ethnicity and an abnormal cerebral ultrasound scan were significantly associated with greater inattention only (non-white ethnicity: 0.58 SD, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.14; abnormal CUSS: 0.61 SD, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.22). Having been transferred within the first 24 hours after birth was significantly associated only with higher hyperactivity/impulsivity at 11 years (0.50 SD, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.98) (Table 5).

At two years of age, a smaller head circumference, internalizing behavior problems and lower PDI scores were associated with inattention at 11 years (OFC per SDS: −0.29 SD, 95% CI −0.45 to −0.13; internalizing problems: 0.29 SD, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.50; PDI per 10 points: −0.30 SD, 95% CI −0.44 to −0.16). A smaller head circumference was also associated with greater hyperactivity/impulsivity (−0.16 SD; 95% CI −0.27 to −0.05), but the coefficient was smaller than that for inattention. Additionally, higher hyperactivity/impulsivity scores were significantly associated with externalizing behavior problems (0.28 SD, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.43), not having received breast milk by discharge from hospital (0.50 SD, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.93) and an abnormal cranial ultrasound scan (0.48 SD, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.90).

By six years of age, neurodevelopmental factors explained 41% of the variance in inattention scores and 31% of the variance in hyperactivity/impulsivity scores. Specifically, a smaller head circumference (OFC per SDS: −0.30 SD, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.13), lower MPC scores (MPC per 10 points: −0.18 SD, 95% CI −0.33 to −0.03), pervasive conduct problems (1.17 SD, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.1) and pervasive peer relationship problems (1.01 SD, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.58) at six years and lower PDI scores at two years (PDI per 10 points −0.20 SD, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.05) were independently associated with greater inattention at 11 years (Table 4). Although MPC scores at six years and PDI scores at two years were highly correlated (R2 = 0.64), for inattention each was significant after adjustment for the other. For hyperactivity/impulsivity, lower MPC scores (MPC per 10 points: −0.11 SD, −0.20 to −0.01), pervasive conduct problems (1.22 SD, 0.54 to 1.90) and pervasive hyperactivity/inattention problems (0.54 SD, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.98) on the SDQ at six years, externalizing behavior problems at two years (0.22 SD, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.38) and non-white maternal ethnicity (0.50 SD, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.90) were associated with higher scores.

DISCUSSION

In this national population-based cohort study, we observed a significant excess of ADHD symptoms in EP children at 11 years of age compared with their term-born peers along both symptom dimensions. In particular, between-group differences were greater for inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity, with average effect sizes of 1.2 SD and 0.5 SD for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores respectively. EP children also had significantly greater symptoms of inattention than hyperactivity/impulsivity on both parent and teacher reports, a pattern of findings that was not observed in the term control group. Although both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity were affected, these results indicate a stronger association of EP birth with the development of attention deficits than with hyperactive or impulsive behaviors. As shown in Figure 1, this may be conceptualized as EP birth shifting the normal distribution of inattention symptoms to the right. Whilst EP children with lower IQ or more severe neurodevelopmental disability had greater inattention scores, there was still a significant excess of inattention symptoms in EP children without disability and after adjustment for IQ.

This pattern of findings has previously been observed in children born very preterm or with ELBW in both dimensional4, 9, 11, 12, 14-16 and diagnostic studies in this5 and other cohorts.14 As noted earlier, this phenotypic profile has led authors to suggest that ADHD following preterm birth may arise from core deficits in attention that are associated with aberrant brain development following delivery at extremely low gestations.5, 35, 36 Indeed, there is increasing evidence for a bi-factor model of ADHD in which disorders characterized by core deficits in attention (ADHD/I) may be considered as neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct from those in which a clinically elevated level of hyperactivity/impulsivity is also present (i.e., ADHD/C or ADHD/H).37, 38 That ADHD sub-types may be characterized as separable disorders with differing underlying neural substrates is illustrated in the case of children born preterm in which the phenotypic profile differs from that of children with ADHD in the general population.2, 8 However, the relatively greater risk for inattention has not been observed in all studies.3, 7, 39 In the present study it is important to note that we also observed a significant increase in hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms in EP children suggesting that the preponderance of inattention is accompanied by a sub-threshold increase in hyperactivity/impulsivity. As such, we would suggest that ADHD following EP birth is primarily rather than purely an attention deficit disorder. The excess of inattention symptoms was not explained by lower general cognitive ability following EP birth in those with IQ in the average range, as EP children with MPC ≥90 still had greater inattention than controls with MPC ≥90 when adjusting for MPC. However, this was not true for hyperactivity/impulsivity which was accounted for by poorer general cognitive ability in EP children with MPC ≥90.

Our exploration of antecedents of ADHD symptoms in EP children revealed clear differences in the strength of associations between clinical and neurodevelopmental factors and ADHD symptom domains. Indices of poor brain growth or neurological function, including smaller head circumference at two and six years, cognitive impairment, lower developmental test scores at two years, and poorer IQ and neuropsychological skills at six years, had significantly stronger associations with symptoms of inattention than with hyperactivity/impulsivity. Conversely, male sex and low parental occupational status were significantly associated only with the development of hyperactivity/impulsivity on univariable analyses. These results support the hypothesis that inattention following EP birth is associated with aberrant brain development and suggest that factors affecting the development of ADHD may be symptom specific. Indeed, studies of children with ADHD in community based samples have shown that inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive behaviors are associated with different neuropsychological profiles37 and this is borne out in a number of studies of children born preterm. Nadeau and colleagues40 observed different mediators of the relationship between EP birth and ADHD symptoms, with hyperactivity/impulsivity being mediated by general intellectual delay and inattention by deficits in working memory. In children born EP/ELBW, neuropsychological measures of attention have also been differentially associated with inattention versus hyperactivity/impulsivity, suggesting that the correlates of ADHD are symptom-specific.16 However, Mulder and colleagues reported that processing speed and working memory were associated with both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in VP children, although this was based on a small sample and used ≤3 questionnaire items to assess ADHD symptom dimensions.10

For both symptom domains, not having received breast milk by discharge from hospital was associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in both univariable and multivariable analyses. Although the lack of breast milk has previously been associated with the development of Autism Spectrum Disorders in this cohort,41 this association is complex to interpret; it is difficult to disentangle to the degree to which factors such as early attachment, neurological deficits, gastrointestinal disorders and the putative role of breast milk in neuronal development contribute to psychiatric outcomes.

The results of our multivariable analyses indicate potential risk factors for later attention difficulties in EP children and may be helpful in identifying children at risk in routine clinical follow-up. Those with abnormal cranial ultrasound scans during the neonatal period were at higher risk, as were those born to non-white mothers and with smaller head circumference and poor developmental test scores, particularly for motor development, at two years of age. Interestingly, high scores on parent completed behavioral screening tools at two and six years of age were associated with greater ADHD symptoms at 11 years. In general, internalizing problems and peer relationship difficulties were associated with an increased risk for inattention, and externalizing difficulties or conduct problems with an increased risk for hyperactivity/impulsivity. This is suggestive of differing comorbid symptoms for ADHD subtypes in this population and supports early identification of children at risk through easily applied screening tests and detection of potentially modifiable risk factors. Indeed, parent ratings on both the CBCL and SDQ have previously been shown to predict later psychiatric disorders, and we have previously reported that behavioural screening measures have good predictive validity in preterm cohorts.6 As such, screening for behavior problems in preterm survivors may have clinical utility for identifying children at risk and timely identification of children with attention deficits may facilitate the provision of early intervention strategies. Behavioral parent training is frequently recommended as an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for improving functional outcomes in children at risk of developing ADHD42, 43 and may therefore be offered to preterm children who exhibit risk factors on preschool assessments. There is also emerging interest in the efficacy of attentional training in infancy and early childhood for improving cognitive control and preventing ADHD symptoms.44, 45 However it remains an open question whether such approaches may help ameliorate attentional impairments in children born EP.

In general, parent ratings of ADHD symptoms were higher than teacher ratings for EP children by up to 0.4 SD, but this was not observed in the control group. This may be due to parents’ sensitivity and perception of their child’s birth status compared to teachers who may not be aware of a child’s clinical history. Teachers also have several children to compare to in the class which may result in underrating compared to parents. It has also been noted that teachers’ ADHD scores can show instability over time32 and because we cannot tell how knowledge of children’s birth status may have affected individual's responses we used the average of the parent and teacher's scores for exploring antecedents of ADHD symptoms.

The strengths of this study lie in the use of longitudinal data from a large national, population-based study of outcomes following EP birth. Validated tools were used to assess neurodevelopmental outcomes from two to six years of age and ADHD symptoms at 11 years of age. Examiners were also blind to children’s group allocation and clinical history when conducting assessments. We also obtained multi-informant data on behavioral outcomes at both six and 11 years as recommended for assessing childhood mental health outcomes.29, 46 However, despite the sample being drawn from the whole British Isles, there are limitations to our conclusions. Dropout analyses revealed that EP children who were not assessed at 11 years of age were more likely to have poorer neurodevelopmental and cognitive outcomes at 2.5 and 6 years of age than those who were assessed. As poor neurodevelopmental outcomes were associated with increased ADHD symptoms, particularly inattention, the selective dropout may have the effect of underestimating the prevalence and severity of ADHD symptoms in the whole EP population. A sensitivity analysis suggests that the effect on inattention in the total EP population is a slight underestimate (−0.1 SD). However if the relationship between predictors and outcomes in the dropouts versus those assessed is similar (i.e., the data are Missing at Random), the relationships shown should not be biased. We also noted that the parents of EP children had lower occupational status than those of the controls. This may have impacted on our findings in terms of inflating the mean difference in ADHD symptoms between the EP children and controls. Future studies could explore the impact of various indices of socio-economic status on the development of ADHD symptoms in this population and the role of other key factors such as maternal substance abuse or alcohol use. As our findings are based on EP children, caution should be taken if generalizing to children born at later preterm gestations. Future studies should further explore the etiology of ADHD in preterm populations, including those born at more mature preterm gestations, to determine the best approaches to treatment. Such studies should focus on elucidating the specific cognitive and social processes that underlie ADHD symptoms, particularly inattention, to aid in the development of intervention strategies for reducing the severity and impact of such difficulties on everyday functioning. Given the high levels of ADHD and ASD in this population, the co-occurrence of antecedents (e.g., cognitive impairments, not having received breast milk by discharge) and the association of peer relationship difficulties with inattention symptoms, future studies investigating comorbidities in this population are warranted. In addition, we utilized a dimensional approach to explore antecedents of the ADHD symptoms, for which we used parent and teacher reports to assess psychopathology. Future research should explore the role of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological factors in the development of attention deficits measured through direct testing and diagnostic assessments of ADHD. Here we explored the presence of ADHD symptoms which may overestimate hyperactivity/inattention problems compared with diagnostic assessments of ADHD.47 Moreover, the presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety disorders and autism spectrum disorders which are more common among preterm survivors than children in the general population, may have impacted on the associations reported here. Future studies should explore the influence of other psychopathology on ADHD symptoms and the role of neurodevelopmental factors in EP children with comorbid disorders.

In summary, we have shown that EP children are at increased risk for ADHD symptoms, predominantly inattention, which are associated with neuro-cognitive deficits, peer relationship problems and internalizing behaviors earlier in childhood. This may have significant long-term implications as inattention rather than hyperactivity/impulsivity has a greater impact on academic achievement and life chances in preterm children.14 Early cognitive and behavioral assessments may therefore be beneficial for early instigation of support to minimize the impact of these problems on longer term mental health and educational attainment.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: The EPICure Study was funded by the Medical Research Council, London, UK. Neil Marlow receives part funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centre’s funding scheme at UCLH/UCL.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- ADHD RS-IV-

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale- IV

- BSID-II

Bayley Scales of Infant Development II

- CBCL

Child Behavior Checklist

- EP

Extremely Preterm

- IQ

Intelligence Quotient

- K-ABC

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children

- MPC

Mental Processing Composite

- MDI

Mental Development Index of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition

- NEPSY

Developmental; Neuropsychological Assessment

- PDI

Psychomotor Development Index of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SES

Socio Economic Status

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson S, Marlow N. Preterm Birth and Childhood Psychiatric Disorders. Pediatric Research. 2011;69:11r–18r. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212faa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treyvaud K, Ure A, Doyle LW, et al. Psychiatric outcomes at age seven for very preterm children: rates and predictors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:772–779. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hack M, Taylor HG, Schlichter M, et al. Behavioral outcomes of extremely low birth weight children at age 8 years. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:122–130. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31819e6a16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Psychiatric Disorders in Extremely Preterm Children: Longitudinal Finding at Age 11 Years in the EPICure Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:453–463.e451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson S, Marlow N. Growing up after extremely preterm birth: lifespan mental health outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;19:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott MN, Taylor HG, Fristad MA, et al. Behavior disorders in extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children in kindergarten. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:202–213. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182475287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson S, Wolke D. Behavioural outcomes and psychopathology during adolescence. Early Hum Dev. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brogan E, Cragg L, Gilmore C, et al. Inattention in very preterm children: implications for screening and detection. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:834–839. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulder H, Pitchford NJ, Marlow N. Inattentive behaviour is associated with poor working memory and slow processing speed in very pre-term children in middle childhood. Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81:147–160. doi: 10.1348/000709910X505527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson P, Doyle LW. Neurobehavioral outcomes of school-age children born extremely low birth weight or very preterm in the 1990s. JAMA-Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2003;289:3264–3272. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, et al. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samara M, Marlow N, Wolke D. Pervasive Behavior Problems at 6 Years of Age in a Total-Population Sample of Children Born at <=25 Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics. 2008;122:562–573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaekel J, Wolke D, Bartmann P. Poor attention rather than hyperactivity/impulsivity predicts academic achievement in very preterm and full-term adolescents. Psychol Med. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor HG, Hack M, Klein NK. Attention deficits in children with < 750 gm birth weight. Child Neuropsychology. 1998;4:21–34. doi: 10.1076/0929-7049(200003)6:1;1-B;FT049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shum D, Neulinger K, O'Callaghan M, et al. Attentional problems in children born with very preterm or with extremely low birth weight at 7-9 years. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2008;23:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Weber W, et al. Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psychosocial features of DSM subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a clinically referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:185–193. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, et al. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. EPICure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:378–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, et al. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson S, Fawke J, Hennessy E, et al. Neurodevelopmental disability through 11 years in children born before 26 weeks of gestation: The EPICure Study. Pediatrics. 2009:e249–e257. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd Edition. Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achenbach TM. The Manual for the Child Behaviour Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY. A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marlow N, Hennessy E, Bracewell M, et al. Motor and executive function at 6 years of age following extremely preterm birth. Pediatrics. 2007;120:793–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children. American Guidance Service, Inc; Circle Pines, MN: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn J. Searching for justice: the discovery of IQ gains over time. American Psychologist. 1999;54:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolke D, Ratschinski G, Ohrt B, et al. The cognitive outcome of very preterm infants may be poorer than often reported: an empirical investigation of how methodological issues make a big difference. European Journal of Pediatrics. 1994;153:906–915. doi: 10.1007/BF01954744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson S, Hollis C, Marlow N, et al. Screening for childhood mental health disorders using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: the validity of multi-informant reports. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:453–459. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, et al. ADHD Rating Scale-IV. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabiner DL, Murray DW, Rosen L, et al. Instability in teacher ratings of children's inattentive symptoms: implications for the assessment of ADHD. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31:175–180. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181d5a2d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Power TJ, Doherty BJ, Panichelli-Mindel SM, et al. The predictive validity of parent and teacher reports of ADHD symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1998;20:57–81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: Release 10.1 College Station, TX. StataCorp LP; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hille ETM, den Ouden AL, Saigal S, et al. Behavioural problems in children who weigh 1000g or less at birth in four countries. The Lancet. 2001;357:1641–1643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finke K, Neitzel J, Bauml JG, et al. Visual attention in preterm born adults: specifically impaired attentional sub-mechanisms that link with altered intrinsic brain networks in a compensation-like mode. Neuroimage. 2015;107:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diamond A. Attention-deficit disorder (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder without hyperactivity): A neurobiologially and behaviorally distinct idsorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (with hyperactivity) Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:807–825. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grizenko N, Paci M, Joober R. Is the inattentive subtype of ADHD different from the combined/hyperactive subtype? J Atten Disord. 2010;13:649–657. doi: 10.1177/1087054709347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, et al. Attention problems in a representative sample of extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2011;36:57–73. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2011.540538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadeau L, Boivin M, Tessier R, et al. Mediators of behavioral problems in 7-year-old children born after 24 to 28 weeks of gestation. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. J Pediatr. 2010;156:525–531. e522. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelham WE, Jr., Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:184–214. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:527–551. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wass S, Porayska-Pomsta K, Johnson MH. Training attentional control in infancy. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1543–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Halperin JM. Developmental phenotypes and causal pathways in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: potential targets for early intervention? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:368–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bora S, Pritchard VE, Moor S, et al. Emotional and behavioural adjustment of children born very preterm at early school age. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:863–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elgen I, Sommerfelt K, Markestad T. Population based, controlled study of behavioural problems and psychiatric disorders in low birthweight children at 11 years of age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;87:F128–132. doi: 10.1136/fn.87.2.F128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]