Abstract

Background

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide, despite gains in diagnostics and treatments made over the last three decades. Existing markers of ovarian cancer possess very limited clinical relevance highlighting the emerging need for identification of novel prognostic biomarkers as well as better predictive factors that might allow the stratification of patients who could benefit from a more targeted approach.

Patients and methods

A summary of molecular genetics of EOC.

Results

Large-scale high-throughput genomic technologies appear to be powerful tools for investigations into the genetic abnormalities in ovarian tumors, including studies on dysregulated genes and aberrantly activated signaling pathways. Such technologies can complement well-established clinical histopathology analysis and tumor grading and will hope to result in better, more tailored treatments in the future. Genomic signatures obtained by gene expression profiling of EOC may be able to predict survival outcomes and other important clinical outcomes, such as the success of surgical treatment. Finally, genomic analyses may allow for the identification of novel predictive biomarkers for purposes of treatment planning. These data combined suggest a pathway to progress in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer and the promise of fulfilling the objective of providing personalized medicine to women with ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

The understanding of basic molecular events in the tumorigenesis and chemoresistance of EOC together with discovery of potential biomarkers may be greatly enhanced through large-scale genomic studies. In order to maximize the impact of these technologies, however, extensive validation studies are required.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, genomics, biomarkers, clinical trials

introduction

According to the World Health Organization, epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for over 150 000 deaths each year worldwide. In the United States alone, ∼22 000 new cases are diagnosed each year resulting in 15 000 deaths, making EOC the most lethal gynecologic cancer [1].

The high mortality rate associated with EOC is primarily due to the clinical presentation and diagnosis; most women present with symptoms associated with advanced disease which often extends beyond the ovary to involve the peritoneal cavity. Standard treatment of EOC includes cytoreductive surgery (whenever possible) followed by platinum-based chemotherapy, although more and more primary chemotherapy followed by surgical treatment is often utilized in women who are not ideal candidates for surgery at presentation. While ∼80% of women presenting with EOC initially respond to this therapy, most will relapse. Although some data suggest that survival after the initial diagnosis of EOC has improved over time, there has been no real progress in the rate of cure, which in the United States has improved from 12% in the 1970s to only 14% by the year 2000 [2]. Death from disease is often heralded by the evolution of drug-resistant disease [3]. Taken together, these statistics highlight the importance of research in ovarian cancer, including the need for novel treatment approaches, therapies, and better prognostic and predictive biomarkers.

Improvement in the outcomes for women with EOC may be achieved through a better understanding of the biology of this disease, which can be accomplished by using modern tools, including high-throughput technologies, such as comparative genomic hybridization and gene expression profiling [4–8] and next-generation sequencing [9]. In this paper, we review studies discussed at the 10th International Symposium on Advanced Ovarian Cancer, held in Valencia, Spain.

clinical and genetic aspects of EOC by histology

It is now recognized that EOC is a highly heterogeneous disease characterized by significant genomics, morphologic, and clinical differences observed between categories [10]. The most prevalent histologic subtype of EOC is high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), accounting for 50%–60% of all EOC. These tumors are thought to more often arise from the fallopian tube rather than ovarian surface epithelium, and have been reported to be associated with serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma as a precursor lesion [11]. Clinically, they usually present at advanced stage with diffuse carcinomatosis. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Project revealed that 10% of cases of advanced HGSC are associated with the presence of multiple areas of chromosomal gain or loss containing over 30 growth-stimulatory genes amplifications [9]. In addition, activating mutations in TP53 were shown to be a hallmark of HGSC (>90%). BRCA1/2, homologous recombination (HR) repair effectors were also found inactivated in an overall rate of 20% of the patients, due to either germline or somatic mutation and epigenetic silencing. An additional group of low-frequency mutations (PALB2, RAD51, fanconi-anemia pathway) was demonstrated to have a common tumorigenic mechanism linked to HR deficiency as BRCA1/2, and together account for up to half of late-stage serous OC cases.

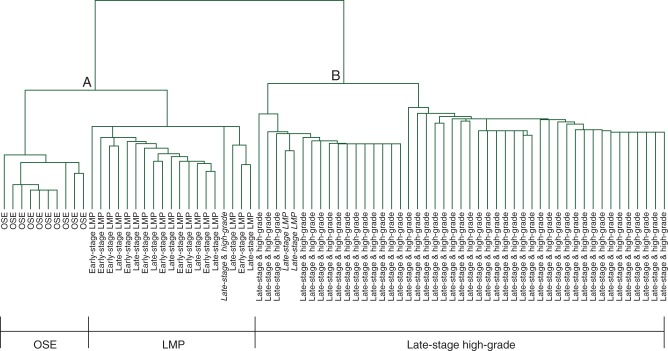

In contrast, low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC) represents 5% of EOC [12]. Unlike HGSC, it is characterized by a relatively indolent behavior [13, 14]. In addition, LGSC is often not as sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy as HGSC, and as a result, surgery is the mainstay of treatment in these diseases. Existing clinical [15] and genomic data indicate crucial differences between LGSC and HGSC [16, 17], as well as some similarities between LGSC and tumors of low malignant potential (LMP) [12, 18–22] (Figure 2). For example, expression profiling of HGSC revealed enhanced expression of genes involved in chromosomal instability and cell proliferation, whereas profiling of LGSC revealed less overall karyotype instability and lower rate of mutations [19]. These LGSC have mutations in BRAF and KRAS, leading to the constitutive activation of MAPK/Erk signaling and its downstream pathway and result in an enhancement of tumor cell survival and proliferation.

Figure 2.

Expression profiles of low malignant potential/low-grade serous and high-grade carcinomas. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealing an extensive molecular segregation between low malignant potential/low-grade serous and high-grade serous tumors. Adapted from Bonome et al. [19].

These data suggested that inhibition of MAPK hyperactivation may benefit patients with LGSC, which have been shown to have a very poor response to conventional platinum-based therapy. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) conducted a phase II trial (GOG-239) using a small molecule inhibitor of MEK1/2 selumetinib (AZD6244) in women with recurrent LGSC [23]. In this experience, selumetinib induced a response rate of 15%, whereas historically, chemotherapy was associated with a response rate of <5%. In addition, over 65% of patients presented with stable disease, suggesting that a larger clinical benefit could be obtained with this agent. The median progression-free survival was 11 months. Despite these results, the investigators were not able to identify a predictive mutation associated with treatment efficacy. A separate study aimed to identify biologic predictors of long-term response to selumetinib among women with LGSC [24]. Using next-generation sequencing technology with in vitro and in vivo validation studies, several potential factors were identified, including somatic 15-nucleotides’ deletion in the MAP2K1 gene.

The endometrioid subtype, which represent 25% of all EOC cases, is characterized by aberrant PI3K signaling as well as mutations in CTNNB1, the main effector of WNT pathway [25, 26]. Mucinous EOC often have RAS mutations activating its pathway in 50% of cases [27] with HER2 overexpression [28] also present in 19% of cases.

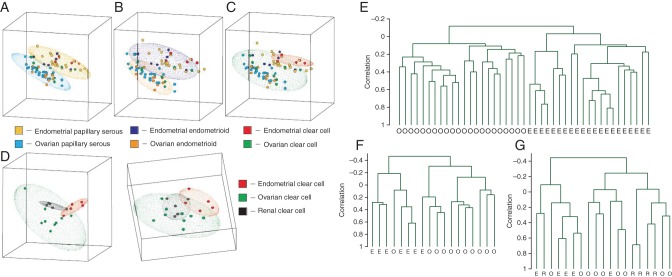

Clear cell EOC often have inactivating mutations in SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factor [29, 30]. When clear cell tumors of ovarian and endometrial origin are compared, they appear to demonstrate a uniform gene expression pattern regardless of their organ of origin. Interestingly, clear cell ovarian cancer has shown to be highly similar to renal cell carcinoma, indicating mTOR pathway and angiogenesis may be therapeutic targets (Figure 1) [26]. Distinct molecular signatures of clear cell EOC include overexpression of hypoxia inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α) and 2 α (HIF-2 α) with activation of this pathway [31, 32]. Preclinical studies that used knockdown assays of key players in hypoxia pathway (ENO-1 and HIF-1α) showed that clear-cell cell lines were sensitive to hypoxia and glucose deprivation [32]. These data informed the design of a currently ongoing phase II clinical trial involving inhibitors of VEGFR and PDGFR for recurrent or persistent clear cell EOC (GOG 254, NCT00979992) [33]. Additionally, PIK3CA mutations [34, 35] supported the basis to test the pathway inhibition through downstream effectors blockade, such as mTOR [36]. Phase II trials are ongoing and interesting results are expected for newly diagnosed CCOC [Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 268, NCT01196429].

Figure 1.

Graphic depiction of principle component analysis of ovarian and endometrial cancers according to histology. Analysis of tumors with serous (A) and endometrioid (B) histology showed two non-overlapping regions separating endometrial (top) from ovarian (bottom) specimens, whereas the analysis of tumors with clear-cell histology (C) showed overlapping elliptical regions. (D) Analysis of tumors according to organ of origin shows three overlapping elliptical regions among ovarian, endometrial, and renal clear cell specimens. Dendrograms produced by unsupervised hierarchical clustering according to (E) serous histology, (F) endometrioid histology, and (G) clear cell histology. O, ovarian samples; E, endometrial samples; R, renal samples. Adapted from Zorn et al. [26].

generation of clinically relevant signatures in ovarian cancer

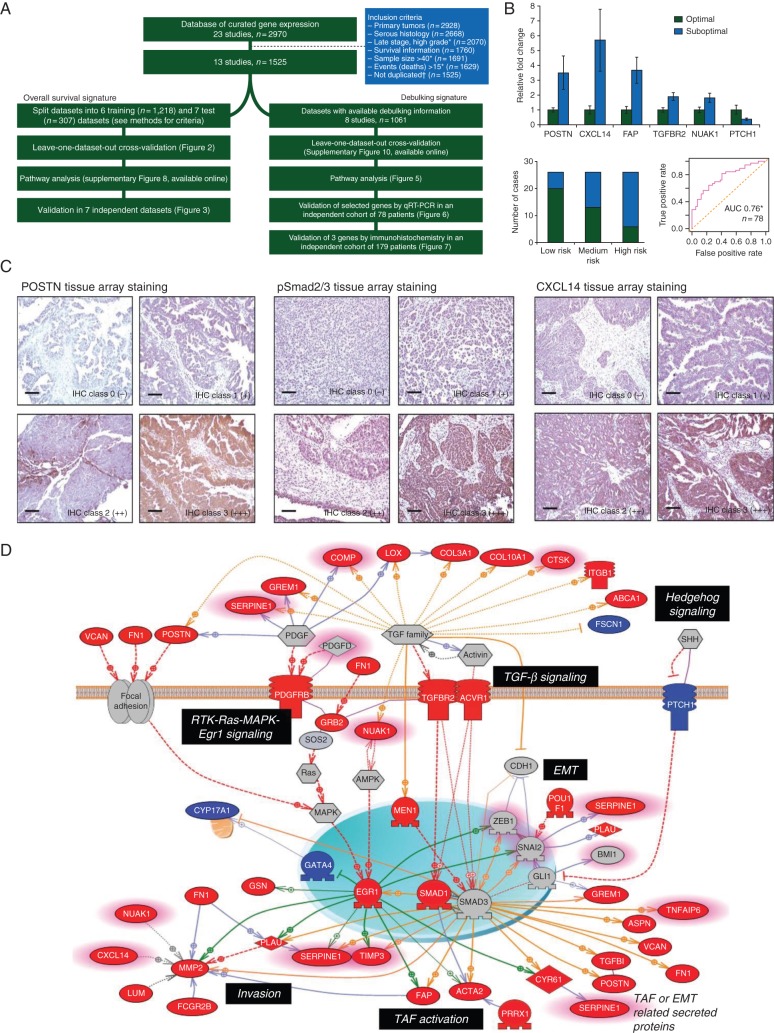

Although a number of microarray datasets have been published, efforts to interrogate them remain premature to date and none have had the power and robustness to inform clinical decisions. To address this need, our group created a centralized curated database [37] comprised of datasets focused on women with HGSC treated surgically, in whom completely annotated survival information was available, and with a sample size of ≥40. Furthermore, we carefully excluded duplicates that were present among the data. Our goal was to obtain a signature based on meta-analysis [38] which might also stratify patients prognostically. In comparison with existing prognostic factors and gene signatures, the meta-analysis signature better carried out than all previous established models, with the highest capability of patient stratification into low- and high-risk groups of overall survival. While encouraging, the signature requires prospective validation (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of 1525 late-stage ovarian cancer samples. (A) Flowchart of the study outlining the steps for training and validating the prognostic models presented in this meta-analysis study. (B) Validation of POSTN, pSmad2/3, and CXCL14 in an independent cohort by immunohistochemistry and Validation of selected genes associated with debulking status by quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR) in the Bonome et al. validation data. (C) Pathway analysis of the debulking signature, using the Pathway Studio 7.1 (Ariadne Genomics) software and a novel signature of 200 debulking-associated genes with suboptimal debulking surgery. Genes are labeled in red when overexpressed in tumors that were subsequently suboptimally debulked. Conversely, genes overexpressed in tumors with optimal cytoreduction are labeled in blue. Genes with predictive power toward poor prognosis based on the meta-analysis are highlighted with pink borders. Red broken arrows indicate direct stimulatory modification. Green arrows indicate EGR-1-based transcriptional regulations. Orange arrows indicate TGF-β/Smad-based transcriptional regulations. Blue solid arrows indicate other direct regulations. Blue broken arrows indicate other indirect regulations. Purple sticks indicate binding. Adapted from Riester et al. [38].

Through the same meta-analytic approach, we also aimed to establish a gene expression signature for predicting the outcome from primary debulking surgery. Our hypothesis assumed the existence of activated pathway profiles deemed to harbor an intrinsic aggressive biology and therefore to identify tumor that would be less likely to be optimally cytoreduced (residual disease >1 cm) [39]. The development of a debulking signature involved validation of selected genes such as POSTN, CXCL14, FAP, NUAK1, PTCH1, and TGFBR2 by qRT–PCR and POSTN, CXCL14, and phosphorylated Smad2/3 by immunohistochemistry in two independent cohorts of patients, and our results indicated that these genes appeared to be independent predictors of cytoreductive surgery (Figure 3B). These results infer a relevant role in tumor dissemination, based on TGFβ signaling activation (Figure 3C). Again, these data require testing in a prospective fashion to determine whether these results are clinically useful.

new target identification for HGSC

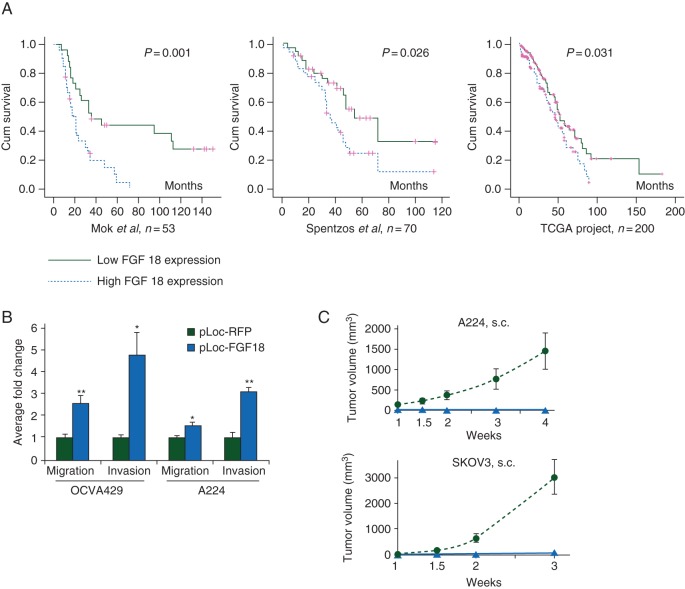

Another potential use for genomic technology is to help identify novel biomarkers for EOC. For example, at the Massachusetts General Hospital, we developed an oligonucleotide array-based comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) analysis, based on microdissected HGSC samples, which showed that amplification of the 5q31–5q35.3 chromosome segment is significantly associated with poor survival [7]. Furthermore, we identified fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF-18), which is located on this chromosomal region, as strongly prognostic for poor survival. FGF-18 was further validated as an independent prognostic biomarker by two other profiling studies [8, 9]. Consequently, functional studies showed FGF-18 in vitro and in vivo promotion of migration, invasion, and tumorigenicity of OC cells (Figure 4) [40]. FGF-18-associated tumor progression appears to proceed through the activation of NF-κβ, with subsequent augmentation in the production of oncogenic cytokines and chemokines, eventually leading to increased tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration, more malignant M2 phenotype polarization, and augmented angiogenesis [41, 42]. Immunohistochemical staining of FFPE samples of 25 human high-grade, late-stage HGSC revealed significant correlation between FGF-18 expression, microvessel density, and TAM infiltration, suggesting that FGF-18 modulated tumor microenvironment by promoting vascularization and recruitment of TAMs [40]. Further expression profiling studies using Affymetrix Human U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip array and validation by qRT–PCR showed that FGF-18 activated multiple signaling pathways such as EGF signaling, TGF-β signaling, JAK/STAT signaling, and NF-κβ signaling. Functional studies using pan-FGFR inhibitor revealed the potential specificity of FGFR4 in FGF-18 signaling which was further confirmed by FGFR4 siRNA knock-down experiments indicating that FGF-18 signals through FGFR4 in ovarian cancer cells of HGSC [40]. Due to genomic proximity and co-amplification of both FGF-18 and FGFR4 found previously [7], we elucidated that this co-amplification may contribute toward the hyperactivation of FGF signaling determining the poor patient survival.

Figure 4.

Identification of FGF18 as a gene with high prognostic capacities in high-grade advanced-stage papillary serous ovarian tumors. (A) The Kaplan–Meier analysis of FGF18 expression in patients in three independent sets of serous ovarian cancer samples (Mok 2009, Spentzos 2004, and TCGA Project 2011) linking FGF18 with poor prognosis. (B) Oncogenic effects of FGF18 on ovarian cancer cells. (B) In vitro FGF18 overexpression stimulates migration and invasion in OVCA429 and A224 cells. (C) In vivo with ectopic FGF18 overexpression promoting tumorigenicity of ovarian cancer cells s.c. inoculated in SCID mice (five mice in each group; triangles, RFP-overexpressing cells; circles, FGF18-overexpressing cells). Adapted from Wei et al. [40].

Currently, FGF signaling can be targeted using several different therapeutic approaches such as receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, receptor-neutralizing antibodies, and FGF ligand traps [43–45]; however, many of those treatments demonstrated important levels of toxicity in a long-term blockade. A soluble decoy receptor FP-1039 capable of neutralizing multiple FGF ligands has recently entered phase II clinical trials for endometrial cancer after successfully completing phase I testing, whereas another phase II triple VEGF/PDGFR/FGFR inhibitor BIBF-1120 has been shown to display lower toxicity and to improve progression-free survival [46]. These novel tools indicate FGF-18/FGFR4 as an actionable signaling pathway, likely to offer a targeted therapy to a subset of ovarian cancer patients with specific enriched activation of this pathway.

conclusions

Although throughout the last three decades, major improvements have been made in the fields of surgical debulking as well as chemotherapy regimes, the long-term survival of EOC patients remains unchanged at ∼30%. With clinicopathological features and traditional molecular predictors such as CA-125 protein proving to be insufficient for improving the overall ovarian cancer outcomes, the importance of understanding the basic molecular biology of EOC is further highlighted. Large-scale high-throughput genomic technologies present us with opportunities for identification of novel biomarkers and drivers of ovarian tumorigenesis and chemoresistance. Nevertheless, comprehensive functional as well as clinical studies are necessary for more integrated validation of those potential biomarkers in light of their implicated significance and application as therapeutic treatment.

funding

The work was supported by NCI grants RC4CA156551-01, R01CA169200-03, R01CA142832-05 and generous support from The Julie Fund.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65(1): 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JD, Chen L, Tergas AI et al. Trends in relative survival for ovarian cancer from 1975 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125(6): 1345–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chornokur G, Amankwah EK, Schildkraut JM, Phelan CM. Global ovarian cancer health disparities. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 129(1): 258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farley J, Fuchiuji S, Darcy KM et al. Associations between ERBB2 amplification and progression-free survival and overall survival in advanced stage, suboptimally-resected epithelial ovarian cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 2009; 113(3): 341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok SC, Bonome T, Vathipadiekal V et al. A gene signature predictive for outcome in advanced ovarian cancer identifies a survival factor: microfibril-associated glycoprotein 2. Cancer Cell 2009; 16(6): 521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darcy KM, Brady WE, McBroom JW et al. Associations between p53 overexpression and multiple measures of clinical outcome in high-risk, early stage or suboptimally-resected, advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 111(3): 487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birrer MJ, Johnson ME, Hao K et al. Whole genome oligonucleotide-based array comparative genomic hybridization analysis identified fibroblast growth factor 1 as a prognostic marker for advanced-stage serous ovarian adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2007; 25(16): 2281–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spentzos D, Levine DA, Ramoni MF et al. Gene expression signature with independent prognostic significance in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2004; 22(23): 4700–4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell D, Berchuck A, Birrer M et al. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011; 474(7353): 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Ovarian cancer. Lancet 2014; 384(9951): 1376–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R et al. TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma—evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol 2012; 226(3): 421–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershenson DM, Sun CC, Lu KH et al. Clinical behavior of stage II–IV low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108(2): 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmeler KM, Sun CC, Bodurka DC et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 108(3): 510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC, Lu KH et al. Impact of age and primary disease site on outcome in women with low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: results of a large single-institution registry of a rare tumor. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(24): 2675–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodurka DC, Deavers MT, Tian C et al. Reclassification of serous ovarian carcinoma by a 2-tier system: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer 2012; 118(12): 3087–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Padilla I, Malpica AL, Minig L et al. Ovarian low-grade serous carcinoma: a comprehensive update. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 126(2): 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gourley C, Farley J, Provencher DM et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for ovarian and primary peritoneal low-grade serous carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014; 24: S9–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anglesio MS, Arnold JM, George J et al. Mutation of ERBB2 provides a novel alternative mechanism for the ubiquitous activation of RAS-MAPK in ovarian serous low malignant potential tumors. Mol Cancer Res 2008; 6(11): 1678–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonome T, Lee J-Y, Park D-C et al. Expression profiling of serous low malignant potential, low-grade, and high-grade tumors of the ovary. Cancer Res 2005; 65(22): 10602–10612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May T, Virtanen C, Sharma M et al. Low malignant potential tumors with micropapillary features are molecularly similar to low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 117(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meinhold-Heerlein I, Bauerschlag D, Hilpert F et al. Molecular and prognostic distinction between serous ovarian carcinomas of varying grade and malignant potential. Oncogene 2005; 24(6): 1053–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May T, Shoni M, Crum CP et al. Low-grade and high-grade serous Mullerian carcinoma: review and analysis of publicly available gene expression profiles. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 128(3): 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V et al. Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(2): 134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grisham RN, Sylvester BE, Won H et al. Extreme outlier analysis identifies occult mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mutations in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(34): 4099–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obata K, Morland SJ, Watson RH et al. Frequent PTEN/MMAC mutations in endometrioid but not serous or mucinous epithelial ovarian tumors. Cancer Res 1998; 58(10): 2095–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zorn KK, Bonome T, Gangi L et al. Gene expression profiles of serous, endometrioid, and clear cell subtypes of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 2005; 11(18): 6422–6430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechsteiner M, Zimmermann A-K, Wild PJ et al. TP53 mutations are common in all subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer and occur concomitantly with KRAS mutations in the mucinous type. Exp Mol Pathol 2013; 95(2): 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anglesio MS, Kommoss S, Tolcher MC et al. Molecular characterization of mucinous ovarian tumours supports a stratified treatment approach with HER2 targeting in 19% of carcinomas. J Pathol 2013; 229(1): 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones S, Wang T-L, Shih I-M et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science 2010; 330(6001): 228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(16): 1532–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anglesio MS, Carey MS, Köbel M et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a report from the first Ovarian Clear Cell Symposium, June 24th, 2010. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 121(2): 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stany MP, Vathipadiekal V, Ozbun L et al. Identification of novel therapeutic targets in microdissected clear cell ovarian cancers. PLoS ONE 2011; 6(7): e21121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson AL, Eisenhauer EL, Herzog TJ. Emerging therapies: angiogenesis inhibitors for ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2015; 20(2): 331–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo K-T, Mao T-L, Jones S et al. Frequent activating mutations of PIK3CA in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2009; 174(5): 1597–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell IG, Russell SE, Choong DYH et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res 2004; 64(21): 7678–7681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takano M, Kikuchi Y, Kudoh K et al. Weekly administration of temsirolimus for heavily pretreated patients with clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a report of six cases. Int J Clin Oncol 2011; 16(5): 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganzfried BF, Riester M, Haibe-Kains B et al. curatedOvarianData: clinically annotated data for the ovarian cancer transcriptome. Database 2013; 2013: bat013–bat013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riester M, Wei W, Waldron L et al. Risk prediction for late-stage ovarian cancer by meta-analysis of 1525 patient samples. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106(5): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang S-J, Bristow RE, Ryu H-S. Impact of complete cytoreduction leaving no gross residual disease associated with radical cytoreductive surgical procedures on survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19(13): 4059–4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei W, Mok SC, Oliva E et al. FGF18 as a prognostic and therapeutic biomarker in ovarian cancer. J Clin Invest 2013; 123(10): 4435–4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson MS, Mok SC. Immunopathogenesis of ovarian cancer. Minerva Med 2009; 100(5): 357–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson-Smith TM, Isaacsohn I, Mercer CA et al. Macrophages mediate inflammation-enhanced metastasis of ovarian tumors in mice. Cancer Res 2007; 67(12): 5708–5716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010; 10(2): 116–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greulich H, Pollock PM. Targeting mutant fibroblast growth factor receptors in cancer. Trends Mol Med 2011; 17(5): 283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding TC, Long L, Palencia S et al. Blockade of nonhormonal fibroblast growth factors by FP-1039 inhibits growth of multiple types of cancer. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5(178): 178ra39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ledermann JA, Hackshaw A, Kaye S et al. Randomized phase II placebo-controlled trial of maintenance therapy using the oral triple angiokinase inhibitor BIBF 1120 after chemotherapy for relapsed ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2011; 29(28): 3798–3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]