Abstract

Context:

Student-athletes may require cognitive rest and academic support after concussion. Athletic trainers (ATs) in secondary schools are uniquely positioned to provide medical care and to collaborate with school professionals while managing concussions. However, little is known regarding return-to-learn policies and their implementation in secondary schools.

Objective:

To examine ATs' perspectives on return to learn, cognitive rest, and communication with school professionals after concussion.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Setting:

Web-based survey.

Patients or Other Participants:

A total of 1124 secondary school ATs completed the survey (28.5% response rate). The majority of participants were employed full time (752/1114 [67.5%]) in public schools (911/1117 [81.6%]).

Main Outcome Measure(s):

School and AT employment characteristics, demographics, number of concussions evaluated annually, and perceptions of school professionals' familiarity with ATs' responsibilities were independent variables.

Results:

Of the ATs, 44% reported having an existing return-to-learn policy. The strongest predictor of a return-to-learn policy was frequent communication with teachers after concussion (odds ratio = 1.5; 95% confidence interval = 1.2, 1.7). Most ATs recommended complete cognitive rest (eg, no reading, television; 492/1087 [45.3%]) or limited cognitive activity based upon symptoms (391/1087 [36.0%]). Common academic accommodations were postponed due dates (789/954 [82.7%]), rest breaks (765/954 [80.2%]), and partial attendance (740/954 [77.6%]). Athletic trainers self-reported as primary monitors of health (764/1037 [73.7%]) and academic progression (359/1011 [35.5%]). The strongest predictor of ATs' communication with school professionals was their perception of school professionals' understanding of ATs' roles.

Conclusions:

Overall, ATs followed best practices for cognitive rest and return to learn after concussion. Although ATs are central to the management of student-athletes' physical health after concussion, school professionals may be better suited to monitor academic progress. Increased communication between the AT and school professionals is recommended to monitor recovery and facilitate academic support for symptomatic student-athletes.

Key Words: sport-related concussion, academic accommodations, return to learn

Key Points

Most athletic trainers followed best practices for cognitive rest and gradual return to learn after concussion.

Less than half of athletic trainers reported having a written return-to-learn policy.

Athletic trainers commonly self-identified as the “point person” to monitor a patient's health and academic progression after concussion; however, school professionals may be better suited to monitor academic progress.

Gradual return to physical activity has become widely accepted as best practice for concussion management.1 The gradual increases in heart rate and intensity of exercise are used to assess the athlete's readiness for the physicality of sport while monitoring for concussion symptoms. More recently, experts1,2 have recommended following a similar progression for return to cognitive activity before return to physical activity. The gradual return to learn consists of (1) cognitive rest, (2) light cognitive activity, (3) return to school (part time and with academic adjustments), (4) increased school attendance with decreased academic adjustments, and (5) full return to school without academic adjustments.2,3 The progression of cognitive and physical activity is intended to prevent the recurrence of symptoms, which may hinder timely and full recovery.3

Cognitive rest (eg, limiting or restricting text messaging, watching television, reading, completing schoolwork) is based upon the conceptual framework that an increase in the brain's energy demands while performing cognitive tasks may exacerbate symptoms.3 Yet compliance with cognitive rest may pose challenges for adolescents during the academic year.4 Patients have often reported returning to school before concussion symptoms have subsided,5 which may prolong recovery and affect academic performance. Previous researchers6,7 have observed an increase in symptoms and a decrease in cognitive performance with bouts of cognitive activity after concussion. However, others8 have not found an association between implementation of cognitive rest and symptom recovery rate. Whereas recommendations for cognitive rest may be appropriate immediately after concussion for symptomatic student-athletes, the duration of cognitive rest and its effectiveness in facilitating the healing process remain unclear.9

To aid the student-athlete's recovery after concussion, temporary academic-support strategies may be necessary. In the school setting, formalized assistance for health-related conditions is available in 2 types: (1) an individualized education program (IEP), and (2) a Section 504 plan.2 An IEP outlines the modifications to schoolwork load and attendance as well as other resources available for students eligible to receive special education services. A Section 504 plan outlines academic accommodations related to a documented health condition, which may be appropriate for students who experience postconcussion syndrome.2 Because most concussions resolve within 2 to 3 weeks, student-athletes will likely not qualify for an IEP or a Section 504 plan; however, informal academic-support strategies may be necessary to balance recovery and prevent cognitive overload throughout the return-to-learn progression.2 School nurses are often involved in the facilitation of 504 plans and have reported their involvement in monitoring adolescents' return to learn after concussion.10 However, little is known regarding athletic trainers' (ATs') role in the return-to-learn process.

Athletic trainers employed in secondary schools are uniquely positioned to assist in the monitoring of health and academic progress after concussion. This positioning to provide medical care within the school setting should imply that ATs are knowledgeable about school systems, are familiar with academic-support strategies, and communicate with school professionals. In addition, ATs' employment characteristics (eg, primary source of salary, employment status) and perceptions of school professionals' understanding of AT responsibilities may affect how ATs navigate school systems and interact with school professionals. Williams et al11 found that ATs hired directly by a school or district were more familiar with academic accommodations. However, little is known regarding the academic support provided to student-athletes after concussion and the AT's role in monitoring health and academic progress. As such, the purposes of this study were to (1) describe the existence of return-to-learn policies in secondary schools, (2) characterize ATs' recommendations for cognitive rest and academic support provided to student-athletes after concussion, (3) identify individuals involved in the communication and monitoring of health and academic progress, and (4) examine factors that predict the existence of a return-to-learn policy and communication between an AT and school professionals throughout the management of concussion. Therefore, we hypothesized that (1) fewer than 50% of ATs would have a formalized return-to-learn policy; (2) ATs would recommend cognitive rest immediately after concussion, and common academic adjustments would include modification to school attendance and delayed due dates; (3) ATs would self-identify as the individuals to monitor health, and the school counselor would be identified to monitor academic progress; and (4) ATs primarily paid through an individual school or school district would be more likely to communicate frequently with school professionals.

METHODS

Participants

A list of 4000 regular and student certified ATs employed in secondary schools was obtained from the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) in November 2013. Of the 4000 ATs invited to participate in the survey, 3943 valid e-mails were delivered and 1249 surveys were accessed (31.7%). Incomplete surveys were eliminated, resulting in 1124 of 3943 (28.5%) complete surveys for analysis. The survey sample was representative of all NATA districts; however, there were no respondents from Alaska. The majority of ATs reported full-time employment status (ie, all job responsibilities were related to athletic training, or approximately 40 h/wk; 752/1114 [67.5%]). Most ATs were employed at a public school (911/1117 [81.6%]) and paid primarily through a school district (512/1070 [47.9%]). Less frequent primary salary sources were payment through an individual school (190/1070 [17.8%]), hospital (177/1070 [16.5%]), physical therapy clinic (101/1070 [9.4%]), or other source (59/1070 [5.5%]). Additional participant demographics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. .

Participant Demographics (N = 1124)

| Characteristic |

n (%)a |

| Athletic training experience, y (n = 1111)b | |

| 0–2 | 134 (12.1) |

| 3–5 | 223 (20.1) |

| 6–10 | 227 (20.4) |

| 11–15 | 163 (14.7) |

| 16–20 | 132 (11.9) |

| ≥21 | 232 (20.9) |

| Experience at current school, y (n = 1107)c | |

| 0–2 | 352 (31.8) |

| 3–5 | 223 (20.1) |

| 6–10 | 237 (21.4) |

| 11–15 | 134 (12.1) |

| 16–20 | 71 (6.4) |

| ≥21 | 90 (8.1) |

| Secondary school setting (n = 1117) | |

| Public school | 911 (81.6) |

| Private school | 197 (17.6) |

| Charter school | 9 (0.8) |

| Title I–designated school (n = 1120) | |

| No | 682 (60.9) |

| I don't know | 224 (20.0) |

| Yes | 214 (19.1) |

| No. of athletic trainers to provide patient care (n = 1119) | |

| 1 | 730 (65.2) |

| 2 | 305 (27.3) |

| 3 | 84 (7.5) |

| Team physician specialty area (n = 1115)d | |

| Orthopaedic | 687 (61.6) |

| General medicine | 288 (25.8) |

| Sports medicine | 64 (5.7) |

| Pediatrics | 47 (4.2) |

| Internal medicine | 31 (2.8) |

| Osteopathy | 31 (2.8) |

| Othere | 36 (3.2) |

| I don't have a team physician | 98 (8.8) |

Percentages were rounded.

Indicates years state license or national credential (Board of Certification) maintained.

Indicates years employed at the current school site.

Participants may have selected more than 1 specialty; therefore, the percentages are calculated from the total number of responses for each item, and the sum of the percentages does not equal 100%.

Includes chiropractic, geriatrics, neurology, physiatry, and unsure of physician specialty.

Instrumentation

Instrument Development

This Web-based survey was part of a larger exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods research investigation on concussion-management practices of ATs employed in secondary schools. The survey instrument was developed to examine current concussion-management practices and academic support provided to student-athletes after concussion. Survey content built upon previous studies on concussion management12,13 and recommendations for assisting with the student-athlete's reintegration to school.14 The survey had 5 sections: (1) AT demographics (6 items), (2) school demographics (6 items), (3) concussion-management policy (3 items), (4) return to learn and academic adjustments (17 items), and (5) satisfaction and resources (4 items). Skip logic was used to individualize the survey on the basis of a participant's responses; the total survey items viewed ranged from 31 to 33 items. For the purpose of this article, demographics (sections 1 and 2) and return-to-learn and academic-adjustment items (section 4) will be discussed.

The AT demographics section requested information regarding the respondent's years of experience (total years credentialed or licensed, years within the secondary school setting, years at the current school), state of employment, primary source of salary funding, employment status, additional credentials or certifications, and number of concussions evaluated annually. School demographics items related to type of setting (eg, public, private, charter school), Title I designation (federal label for low socioeconomic status), number of student-athletes, team physician specialty area, and number of ATs (and employment status) hired to provide on-site patient care. Return-to-learn items asked if the respondent's school had a written return-to-learn policy, and if not, the reasons for not having a written policy at the time of the study. In addition, questions were included regarding academic-support strategies provided, implementation of return to learn, and communication with school professionals.

Instrument Validation and Pilot Testing

Before dissemination, we validated the instrument for face and content validity. The panel of experts and clinicians (N = 20) comprised physicians or neuropsychologists (n = 6), AT faculty or researchers (n = 7), and secondary school ATs (n = 7). Survey items were rated on a scale of 1 to 3 for content and clarity (1 = not relevant content/wording, consider deleting; 2 = consider minor revisions to content/wording; 3 = little to no revision needed). Mean validation rating of the survey items ranged between 2.5 and 3.0, with a mean of 2.9 ± 0.2. Secondary school ATs scored the instrument highest for clarity and content accuracy (mean = 2.9 ± 0.0), followed by physicians and neuropsychologists (mean = 2.9 ± 0.1) and AT faculty and researchers (mean = 2.7 ± 0.2). Due to differences in means between panelist groups, we reassessed open-ended comments provided by AT faculty and researchers to revise the survey further. The final survey instrument consisted of 36 questions.

Procedures

The institutional review board approved the study before dissemination. A purposeful sample of ATs employed in the secondary school setting was invited via e-mail to participate in the Web-based survey between December 4, 2013, and January 3, 2014. The e-mail requested ATs' participation and included the purpose of the survey, the hyperlink to the Web-based survey, and the projected time to complete the survey. Reminder e-mails were sent at the end of weeks 2 and 3 of the study period. Completion of the survey was acknowledgment of implied consent. Anonymous survey data were collected, and no Internet protocol addresses were recorded. Upon completion of the survey, participants could elect to provide contact information in a separate survey and be entered in a weekly drawing for one of four $50 Amazon (Amazon.com, Inc, Seattle, WA) gift cards. Participants' identities were protected by separation of the contact information from the survey data. Raffle winners were contacted and the gift cards were mailed weekly. The participant's contact information was deleted upon receipt of the gift card. On the basis of previous survey investigations, we anticipated a response rate between 25% and 35%.

Data Analyses

Data were exported from the Web-based survey host for analysis. The number of responses for items differed due to skip logic (ie, respondents were directed to a different item according to the previous response) and skipped questions. We calculated descriptive statistics (percentages and frequencies) for demographic and school-based academic-support items. Separate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine variables that predicted the existence of a return-to-learn policy and frequency of communication with school professionals. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. The Cox and Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 values were reported to describe the goodness of fit of the independent variables to the model. Wald scores were obtained to indicate the strength of the predictor variables within the logistic regression model. Inferential statistics were calculated for closed-ended items using standard statistical software (SPSS, version 22; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). All α levels were set a priori at .05.

RESULTS

Return-to-Learn Policy Descriptives

Overall, 84.1% of ATs (915/1088) recommended a gradual return to learn, but only 43.7% of ATs (435/995) reported having a return-to-learn policy. Of the 15.9% (173/1088) of ATs who did not provide return-to-learn recommendations, the rationales for not making these recommendations were lack of school professionals' understanding of concussions (44/146 [30.1%]), lack of school support (28/146 [19.2%]), lack of time to monitor academics (19/146 [13.0%]), lack of time to develop the return-to-learn policy (15/146 [10.3%]), academic expectations of the school (15/146 [10.3%]), no previous cases of delayed recovery (13/146 [8.9%]), or not being part of the AT's responsibility (12/146 [8.2%]).

Return-to-Learn Policy Predictors

The logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of an existing written return-to-learn policy was statistically significant (χ29 [n = 676] = 55.1, P < .001) and accurately predicted 65.5% of the cases (Table 2). Predictor variables inserted into the model resulted in an improvement of 7.8% (Cox and Snell R2) to 10.6% (Nagelkerke R2) in goodness of fit. This range indicates poor to modest fit of these variables within the model. The strongest predictor of the existence of a return-to-learn policy was the AT's frequency of communication with teachers after an athlete's concussion. Athletic trainers who communicated often or always with teachers were 1.5 times more likely to have a written return-to-learn policy (OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.7) than ATs who communicated never or seldom with teachers. Also, the presence of an additional AT to provide patient care (OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.8) and a greater number of concussions evaluated annually (OR = 1.2; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.5) increased the likelihood of having a written return-to-learn policy. Years of experience as a credentialed or licensed AT (P = .92), experience within the secondary school setting (P = .21), experience at the current school (P = .33), primary salary source (P = .14), employment status (P = .10), and licensure status (P = .12) did not make statistically significant contributions.

Table 2. .

Logistic Regression Predicting Return-to-Learn Policy Existence (n = 676)

| Variable |

Wald Scorea |

P |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for Odds Ratio |

| Athletic training experienceb | 0.0 | .92 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.1 |

| Experience at secondary school | 1.6 | .21 | 0.9 | 0.9, 1.0 |

| Experience at current schoolc | 1.0 | .33 | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.1 |

| Employment statusd | 2.7 | .10 | 1.4 | 0.9, 2.0 |

| Salary from school/district | 2.2 | .14 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.9 |

| Concussions evaluatede | 5.4 | .02 | 1.2g | 1.0, 1.5 |

| Communication with teachersf | 19.4 | <.001 | 1.5h | 1.2, 1.7 |

| No. of athletic trainers | 6.4 | .01 | 1.4g | 1.1, 1.8 |

| Licensure status | 2.5 | .12 | 1.8 | 0.9, 3.7 |

| Constant | 24.7 | <.001 | 0.1 |

Indicates strength of the predictor.

Indicates years as a licensed or credentialed athletic trainer in any employment setting. Sample includes respondents with <21 years of experience.

Indicates years as a licensed or credentialed athletic trainer at the current school of employment. Sample includes respondents with <21 years of experience at the current school.

Includes full-time and half-time status only.

Indicates a scale with increments of 5 concussions evaluated annually.

Includes frequency as never/seldom and often/always. Respondents who answered not applicable were not included.

Indicates difference (P < .05).

Indicates difference (P < .01).

Cognitive Rest and Academic-Accommodations Descriptives

To understand ATs' interpretations of cognitive rest, we asked ATs if they typically recommended complete (ie, restriction of all cognitive activity such as television, schoolwork, text messaging), situational (ie, limitation of specific cognitive activity based upon symptoms), partial (ie, limitation of cognitive activity if symptoms reemerge), or no (ie, no suggestions made regarding cognitive activity) cognitive rest. After concussion, ATs typically recommended complete (492/1087 [45.3%]) or situational (391/1087 [36.0%]) cognitive rest to the parent(s) or guardian(s) and student-athletes. Partial (198/1087 [18.2%]) or no (6/1087 [0.6%]) cognitive rest were recommended less often. Common academic accommodations provided were postponed schoolwork due dates (789/954 [82.7%]), allowed rest breaks (765/954 [80.2%]), and partial school attendance (740/954 [77.6%]). Additional academic-accommodation recommendations and the professional who made these recommendations in schools are presented in Table 3. When asked about the effectiveness of academic accommodations after concussion, ATs perceived them to be very effective (631/1073 [59.0%]), somewhat effective (337/1073 [31.4%]), of unsure effectiveness (96/1073 [8.9%]), or not effective (9/1073 [0.8%]).

Table 3. .

Recommendations for and Implementation of Academic Accommodations

| Variable |

n (%)a |

| Accommodation strategies recommended (n = 954) | |

| Postpone schoolwork due dates | 789 (82.7) |

| Rest breaks | 765 (80.2) |

| Partial school attendance | 740 (77.6) |

| No school attendance | 522 (54.7) |

| Excused schoolwork | 502 (52.6) |

| Sunglasses or hat | 442 (46.3) |

| Note taker | 390 (40.9) |

| Classroom transition | 359 (37.6) |

| Change in course load | 309 (32.4) |

| Preferential seating | 303 (31.8) |

| Memory strategies | 148 (15.5) |

| No recommendations | 66 (6.9) |

| Professional able to implement accommodations (n = 959) | |

| Physician | 705 (73.5) |

| Athletic trainer | 488 (50.9) |

| Nurse or health clerk | 298 (31.1) |

| Special education teacher or coordinator | 98 (10.2) |

| School psychologist | 94 (9.8) |

| Other: counselor | 79 (8.2) |

Participants may have selected more than 1 strategy or individual for these questions. Therefore, the sum of the percentages does not equal 100%.

Monitoring of Recovery and Academic-Progress Descriptives

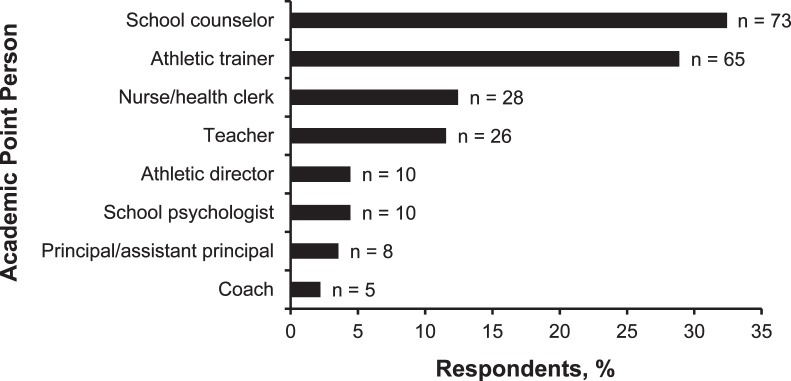

To identify individuals involved in the school-based management of concussion, ATs were asked who monitored and communicated the health status and academic progress of the student-athlete after concussion. Athletic trainers most often identified themselves as the primary “point person” to monitor a student-athlete's health status (764/1037 [73.7%]) and academic progression (359/1011 [35.5%]) after concussion (Table 4). After ATs, school counselors (174/1011 [17.2%]) and nurses or health clerks (120/1011 [11.9%]) were reported as the primary point person to monitor the student-athlete's academic progression. Twenty-one percent of ATs (212/1011) indicated that no point person was currently identified to monitor academic progression. When asked who should monitor academic progression, a school counselor (73/225 [32.4%]) or AT (65/225 [28.9%]) was cited as the most likely candidate for this responsibility (Figure).

Table 4. .

Summary of “Point Persons” Identified to Monitor Health (n = 1037) and Academic Progress (n = 1011)

| Point Person |

Health and Recovery, n (%)a,b |

Academic Progress, n (%)b,c |

| Athletic trainer | 764 (73.7) | 359 (35.5) |

| Principal or assistant principal | 115 (11.1) | 24 (2.4) |

| No one currently identified | 86 (8.3) | 212 (21.0) |

| Athletic director | 27 (2.6) | 26 (2.6) |

| School counselor | 22 (2.1) | 174 (17.2) |

| Coach | 11 (1.1) | 8 (0.8) |

| Teacher | 5 (0.5) | 75 (7.4) |

| School psychologist | 4 (0.4) | 13 (1.3) |

| Nurse or health clerk | 3 (0.3) | 120 (11.9) |

Indicates that the professional was described as one who monitors the student-athlete's symptoms and return-to-play status to communicate with the family and school professionals.

Percentages were rounded.

Indicates that the professional was described as one who monitors the student-athlete's return to learn and collects teachers' feedback to communicate with the family and medical professionals.

Figure. .

Potential “point person” to monitor academic progress (n = 225). This figure represents athletic trainers' identification of a potential academic point person in schools without a previously identified professional for this role.

Communication With School Professionals' Descriptives

In most cases, ATs did not communicate frequently with school professionals after a student-athlete sustained a concussion. Athletic trainers communicated often or always after a concussion with the athletic director (728/1010 [72.1%]) and school nurse or health clerk (655/1003 [65.3%]). The least frequent communication (ie, never or sometimes) occurred with the school psychologist (616/1005 [61.3%]) and school counselor (605/1049 [57.7%]). The distribution of ATs' communication frequency with school professionals is displayed in Table 5.

Table 5. .

Distribution of Athletic Trainers' Frequency of Communication With School Professionals After Concussion

| Communication With School Professionals |

n (%)a |

| Principal or assistant principal (n = 1043) | |

| Never or sometimes | 590 (56.6) |

| Often or always | 439 (42.1) |

| Not applicable | 14 (1.3) |

| School psychologist (n = 1005) | |

| Never or sometimes | 616 (61.3) |

| Often or always | 85 (8.5) |

| Not applicable | 304 (30.2) |

| Counselor (n = 1049) | |

| Never or sometimes | 605 (57.7) |

| Often or always | 411 (39.2) |

| Not applicable | 33 (3.1) |

| Teacher (n = 1044) | |

| Never or sometimes | 515 (49.3) |

| Often or always | 518 (49.6) |

| Not applicable | 11 (1.1) |

| School nurse or health clerk (n = 1047) | |

| Never or sometimes | 286 (27.3) |

| Often or always | 681 (65.0) |

| Not applicable | 80 (7.6) |

| Athletic director (n = 1055) | |

| Never or sometimes | 288 (27.3) |

| Often or always | 758 (71.8) |

| Not applicable | 9 (0.9) |

Percentages were rounded.

To understand part of the dynamics between ATs and school professionals, we asked ATs their level of agreement with this statement: “School professionals (teachers, counselors, administrators) are familiar with athletic training and my job responsibilities.” Most ATs agreed (598/1067 [56.0%]) or strongly agreed (182/1067 [17.1%]) that school professionals were familiar with AT responsibilities. Fewer ATs were not sure (94/1067 [8.8%]), disagreed (145/1067 [13.6%]), or strongly disagreed (48/1067 [4.5%]).

Communication With School Professionals' Predictors

To determine the factors that predicted ATs' frequency of communication with school professionals, we conducted separate logistic regression analyses (Table 6). These logistic regression models were statistically significant for school counselors (P < .001), school psychologists (P < .001), school nurses or health clerks (P < .001), teachers (P < .001), and principals or assistant principals (P < .001). The model for predicting the likelihood of communication frequency with athletic directors was not significant (P = .27). Athletic trainers' perceptions that school professionals' were familiar with ATs' responsibilities was the strongest predictor of communication frequency. Athletic trainers who agreed or strongly agreed that school professionals were familiar with ATs' responsibilities were 1.6 times more likely to communicate often or always with a counselor (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.3, 1.9) or school psychologist (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.2). This perceived familiarity was also associated with increased likelihood of communicating with a teacher (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.4, 1.9), school nurse or health clerk (OR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.5), or principal or assistant principal (OR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.5). In addition, primary salary source was a strong predictor of communication frequency. Athletic trainers paid primarily through a school or district were 2.5 times (OR = 2.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 5.2) more likely to communicate often or always with a school psychologist, 2.2 times (OR = 2.2; 95% CI = 1.5, 3.2) more likely with a counselor, 2.0 times (OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.4, 2.9) more likely with a school nurse or health clerk, and 1.7 times (OR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.3) more likely with a teacher.

Table 6. .

Logistic Regression Predicting the Likelihood of Communication Frequency With School Professionals

| Variable |

School Counselor (n = 731) |

School Psychologist (n = 505) |

School Nurse or Health Clerk (n = 695) |

Teacher (n = 744) |

Principal or Assistant Principal (n = 744) |

|||||

| Wald Score |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Wald Score |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Wald Score |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Wald Score |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Wald Score |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Athletic training experiencea | 7.8 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)b | 0.5 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 5.2 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)c | 0.7 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 0.1 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) |

| Experience at current schoold | 2.7 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 2.4 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.1 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 4.5 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)f | 2.7 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) |

| Employment statuse | 0.3 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.0 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.7 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2)c | 1.2 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 3.9 | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0)f |

| Salary from school/district | 17.4 | 2.2 (1.5, 3.2)b | 5.8 | 2.5 (1.2, 5.2)c | 14.4 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9)b | 9.0 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3)e | 1.6 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) |

| Concussions evaluatedf | 5.4 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6)c | 1.0 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 27.7 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.0)b | 0.6 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 3.6 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) |

| Role familiarity | 24.2 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9)b | 7.1 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2)c | 7.6 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5)b | 33.7 | 1.6 (1.4, 1.9)e | 11.3 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5)e |

| No. of athletic trainers | 11.7 | 1.9 (1.3, 2.7)b | 1.9 | 1.5 (0.8, 2.7) | 3.9 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2)c | 9.7 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4)e | 0.6 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

| Constant | 75.1 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 31.2 | 0.1 | 24.7 | 0.1 | 11.8 | 0.3 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Indicates years as a licensed or credentialed athletic trainer in any employment setting. Sample includes respondents with <21 years of experience.

Indicates difference (P < .01).

Indicates difference (P < .05).

Indicates years as a licensed or credentialed athletic trainer in the current school of employment. Sample includes respondents with <21 years of experience at the current school.

Includes full-time and half-time status only.

Indicates the number of concussions evaluated annually along a scale in increments of 5.

Athletic trainers' experience, employment status, number of concussions evaluated annually, and number of ATs hired to provide patient care also predicted communication frequency with school professionals. Athletic trainers with more years of experience as credentialed or licensed were 1.1 times more likely to communicate often or always with a counselor (OR = 1.1; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.1) or school nurse or health clerk (OR = 1.1; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.1). In addition, more years of experience at the current school predicted ATs' communication frequency with teachers (OR = 1.1; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.1). Similarly, ATs employed full time were 1.4 times (OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.0) more likely to communicate often or always with the principal or assistant principal and 0.8 times (OR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.6, 1.2) more likely to communicate with the school nurse or health clerk.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this investigation were mostly in line with our hypotheses: (1) Less than half of ATs reported having a return-to-learn policy within the school or district; (2) ATs recommended cognitive rest immediately after concussion, and common academic adjustments were modification to school attendance and delayed due dates; (3) ATs self-identified as the individuals to monitor health, yet they also self-identified as the individuals to monitor academic progress; and (4) ATs primarily paid via an individual school or school district were more likely to communicate frequently with school professionals.

Return-to-Learn Policy

Although 84.1% of ATs recommended a gradual return to learn after concussion, only 43.7% reported having a written return-to-learn policy. Our findings were greater than the 24.3% of Ohio school principals who reported having a school concussion policy that specifically addressed academic-support strategies after concussion15 but were consistent with recent findings10 in school nurses. This result may suggest an increasing trend of schools developing and implementing return-to-learn policies. As return to learn becomes widely accepted as part of the concussion-management process, ATs may benefit from reviewing the Colorado “Reduce, Educate, Adjust, Pace” Plan14 or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's “Head's Up Toolkit for Schools”16 and sharing these materials with school professionals. Although state concussion laws exist across the United States, few states discuss or require academic support after concussion. Virginia17 and Nebraska18 have added return to learn to their concussion-related legislation, and we anticipate that more states will follow over time. As such, ATs can continue to assist in the development and implementation of a return-to-learn policy.

Cognitive Rest and Academic Support

Of surveyed ATs, 81% recommended complete cognitive rest or restrictions on the basis of specific symptoms, which is consistent with current recommendations for immediate concussion management.1 However, 55% of ATs in our study recommended school absence if a student-athlete was symptomatic, which may be beyond the AT's scope of practice and may interfere with school policy.1,11 Although researchers have observed functional deficits after cognitive activity6 and have recommended 3 to 5 days of complete cognitive rest after concussion,7 others8,19 have not corroborated these findings. In fact, patients who were advised to follow 5 days of strict cognitive rest experienced more daily postconcussion symptoms and slower symptom resolution than patients who were instructed to rest for a few days before gradually returning to school and activity.20 In some cases, student-athletes may be anxious to make up schoolwork and interact with friends, which may result in a premature return to school with or without academic support.21 Thus the return to school can present a particular challenge when balancing rest, cognitive activity, and completion of schoolwork. It is likely that an individualized period of moderate cognitive rest is best; further research is warranted before recommending multiple school-day absences while recovering.8,20

To enhance schoolwide implementation, a concussion-management team rather than the AT alone should facilitate cognitive rest and academic-support recommendations. Of the ATs surveyed, 73.5% reported that physicians were able to implement academic accommodations after concussion. The reliance on a physician's note can be problematic for student-athletes without immediate access to a physician who is knowledgeable about concussion management and academic support. In a survey22 of primary care physicians in Philadelphia, only 28% made return-to-learn recommendations during the initial visit, and 43% made these recommendations at a follow-up visit for patients with lingering symptoms. Other researchers23 found that physicians reported a lack of specific training about educating families regarding concussions and academic accommodations or perceived that it was not their responsibility to make these recommendations. Whereas physicians are encouraged to recommend academic-support strategies at the discretion of teachers,2 student-athletes may also benefit from a school-based policy that allows temporary support in the absence of a physician's note.

At the time of our study, the term academic accommodations was used, yet some researchers currently prefer (1) academic adjustments when referring to informal academic-support strategies, (2) academic modifications when referring to formal academic-support strategies, and (3) academic accommodations when referring to formal long-term special education needs.2 The foundation of academic accommodations is based upon long-lasting effects of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury and is not specific to concussion. School professionals are familiar with IEPs and Section 504 plans, but obtaining these resources may take additional time and they are mostly relevant for student-athletes who experience a protracted recovery.21 Regardless, the academic demands of secondary school education may warrant the facilitation of timely, informal academic adjustments to prevent falling behind and to reduce school-related anxiety.4 Athletic trainers can help bridge the gap between medical recommendations and school implementation by becoming more familiar with return-to-learn resources and school and district policies and by communicating more frequently with school professionals.

Communicating Health and Academic Progress

Identification of members within the family and the medical and school concussion-management teams is recommended to streamline follow-up communication regarding the student-athlete's recovery.14 It is not surprising that 73.7% of surveyed ATs identified themselves as the primary individual to monitor the health and recovery of the student-athlete after concussion. It is interesting that the principal or assistant principal (11.1%) was identified as monitoring health more often than the school nurse or health clerk (0.3%). It is possible the principal or assistant principal was involved due to concerns regarding school liability or school attendance. It is also likely that school nurses' availability may limit their ability to provide continuity of care for student-athletes after concussion. According to the National Association of School Nurses, 45% of schools have a full-time nurse and 30% have a part-time nurse who works in multiple schools.24 Lacking time to care for a student after concussion has been reported as a barrier to school nurses' involvement within school-based concussion management.25

In regard to monitoring academic progression, it is surprising that many ATs (35.5%) identified themselves as the academic point person more frequently than they identified the school counselors (17.2%) or school nurses or health clerks (11.9%). Whereas the AT may begin the return-to-learn conversation, she or he typically does not have access to student-athletes' academic files and lacks specific training on academic accommodations.11 An AT may serve as the academic point person and conduit to school professionals; however, we recommend that a school professional (eg, school counselor, school nurse) with training in academic accommodations and the response-to-intervention process should implement appropriate academic adjustments. In a survey10 of school nurses, 58% reported involvement in the return-to-learn progression, whereas 31.1% of ATs in our study reported school nurses' ability to implement academic accommodations. It is possible that school nurses employed at schools without an AT may be more involved in the return-to-learn process or that ATs may not be fully aware of school nurses' ability to implement accommodations. It is concerning that 21.0% of ATs in our study indicated that no individual had been identified to fulfill this role. It is unclear how and if progress monitoring occurs for student-athletes in schools without a developed policy and concussion team. This lack of a plan or identified team may indicate the student-athlete and family are solely responsible for determining the necessity of school absence(s) or may not receive needed academic support upon return to the classroom.

Smooth reintegration to school and full recovery require communication among the multidisciplinary school-based concussion-management team.2 Athletic trainers in the current investigation did not frequently communicate with school professionals after concussion, which may affect the support provided to symptomatic student-athletes. Lack of communication between school nurses and the health care professional who diagnosed the concussion has been reported as the primary barrier to school nurses' involvement in the return-to-learn process.25 In our study, more frequent communication with teachers increased the likelihood of having a return-to-learn policy; however, it is unclear whether having a policy facilitated communication or communication led to the development of a policy. In addition, 65.3% of ATs in our study indicated they communicated often or always with school nurses after concussion, whereas Williams et al26 reported that 37.1% of ATs collaborated with school nurses while managing concussions. This increase in communication may stem from conversations regarding return to learn or may highlight a distinction between ATs' and school nurses' communication versus use of an interdisciplinary collaborative concussion-management approach.

Predictors of Communication With School Professionals

The strongest predictor variables of frequent communication with school professionals were (1) ATs' perceptions of school professionals' strong familiarity with an AT's responsibilities and (2) primary source of salary via the school or district. Little is known regarding the perceptions of and relationships between ATs and school professionals; yet coaches' understanding of an AT's role has been associated with positive working relationships.27 Furthermore, previous researchers28 have emphasized the importance of communication between ATs and coaches in the development and maintenance of positive relationships. It is plausible the ATs' perception of school professionals' familiarity with AT responsibilities and established relationships contributed to increased communication with school professionals. These relationships may have been fostered by an AT's knowledge of the school system and functioning as a school-based employee. Direct employment by the school or district has been associated with ATs' increased familiarity with academic accommodations, which may be due to their exposure to school and educational policy or interaction with other school professionals during on-campus trainings.11 Whereas our predictive models were statistically significant, the ORs were low, so the hiring and evaluation of ATs should not be based on these models. However, we believe further exploration of employment models and working relationships in secondary schools is necessary to better understand how to enhance school-based health care and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study is not without limitations. The 28.5% response rate was lower than desired; however, this rate is consistent with other survey-based research published in athletic training. Anonymous data collection, participant gift card incentives, and reminder e-mails were used to increase the response rate and encourage honest responses. Predictive variables in our study do not explain causation, and complex employment characteristics, such as the utilization of graduate-assistant ATs, may have resulted in the wide variation of participant responses. Our findings regarding the employment model should be cautiously interpreted because employment models vary and ATs may not have accurately identified the primary source of their salaries. However, ATs' perceptions of employment characteristics may still be relevant to understanding the connection to their perceived employer and navigation within the secondary school. In addition, the reader should also be cautious in generalizing results for ATs employed less than part time or with 21 or more years of experience. Regression analyses did not include these variables to assess a continuous scale and avoid outliers in employment status because few ATs reported less than part-time status. In general, further exploration of ATs' employment characteristics in the secondary school setting and their influence on school-based policy and patient care is warranted.

Whereas the survey contained mostly descriptive data, we felt it was necessary to collect this information to describe ATs' perspectives on academic support provided after concussion and communication with school professionals. Our findings did not capture other school professionals' perspectives to confirm an accurate portrayal of academic-support strategies provided, yet they can aid in ATs' discussion with school professionals regarding return to learn. Investigators should continue to explore the collaboration of ATs and school professionals after a student-athlete's concussion, which may inform professional socialization practices and interprofessional education programs within secondary schools. These findings can be incorporated into athletic training and teacher education program curricula and enhance the care provided within secondary schools.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, ATs typically followed best practices for cognitive rest and reported that adjustments to school attendance and work due dates were common after concussion. However, schools may benefit from interdisciplinary training on individualized roles in the return-to-learn process and implementation of a school-based concussion-management approach. Whereas most ATs were identified as the primary person to monitor health after concussion, many ATs also reported being the person to monitor academic progress. In other cases, no individual had been assigned to assist with monitoring the student-athlete's academic progress after concussion. Identifying an individual(s) with training in academic accommodations to monitor academic progression is necessary for implementation of academic adjustments, reduction of academic adjustments as symptoms improve, and completion of return to learn before return to physical activity. Increased communication between ATs and school professionals is recommended to aid in the monitoring of a student-athlete's full academic and physical recovery after concussion.

REFERENCES

- 1. . Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014; 49 2: 245– 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. . Halstead ME, McAvoy K, Devore CD, et al. Returning to learning following a concussion. Pediatrics. 2013; 132 5: 948– 957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. . Master CL, Gioia GA, Leddy JJ, Grady MF. Importance of “return-to-learn” in pediatric and adolescent concussion. Pediatr Ann. 2012; 41 9: 1– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. . Ransom DM, Vaughan CG, Pratson L, Sady MD, McGill CA, Gioia GA. Academic effects of concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015; 135 6: 1043– 1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. . Carson JD, Lawrence DW, Kraft SA, et al. Premature return to play and return to learn after a sport-related concussion: physician's chart review. Can Fam Physician. 2014; 60 6: e310– e315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. . Covassin T, Crutcher B, Wallace J. Does a 20 minute cognitive task increase concussion symptoms in concussed athletes? Brain Inj. 2013; 27 13–14: 1589– 1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. . Brown NJ, Mannix RC, O'Brien MJ, et al. Effect of cognitive activity level on duration of post-concussion symptoms. Pediatrics. 2014; 133 2: e299– e304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. . Gibson S, Nigrovic LE, O'Brien M, Meehan W., III. The effect of recommending cognitive rest on recovery from sport-related concussion. Brain Inj. 2013; 27 7–8: 839– 842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. . Moser RS, Glatts C, Schatz P. Efficacy of immediate and delayed cognitive and physical rest for treatment of sports-related concussion. J Pediatr. 2012; 161 5: 922– 926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. . Olympia RP, Ritter JT, Brady J, Bramley H. Return to learning after a concussion and compliance with recommendations for cognitive rest. Clin J Sport Med. 2016; 26 2: 115– 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. . Williams RM, Welch CE, Parsons JT. Valovich McLeod TC. Athletic trainers' familiarity with and perceptions of academic accommodations in secondary school athletes after sport-related concussion. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 3: 262– 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. . Covassin T, Elbin , III, Stiller-Ostrowski JL. Current sport-related concussion teaching and clinical practices of sports medicine professionals. J Athl Train. 2009; 44 4: 400– 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. . Notebaert AJ, Guskiewicz KM. Current trends in athletic training practice for concussion assessment and management. J Athl Train. 2005; 40 4: 320– 325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. . REAP the benefits of good concussion management. Rocky Mountain Youth Sports Medicine Institute Web site. http://www.rockymountainhospitalforchildren.com/sports-medicine/concussion-management/reap-guidelines.htm. Published 2013. Accessed July 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. . Heyer GL, Weber KD, Rose SC, Perkins SQ, Schmittauer CE. High school principals' resources, knowledge, and practices regarding the returning student with concussion. J Pediatr. 2015; 166 3: 594– 599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. . Heads up to schools: know your concussion ABCs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/headsup/schools.html. Published 2012. Accessed July 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. . Student-athletes; Board of Education shall amend its guidelines for policies on concussions. HB 1096, ch 349 ( Va 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18. . LB 923, 103rd Leg, 2nd Sess ( Neb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19. . Eisenberg MA, Andrea J, Meehan W, Mannix R. Time interval between concussions and symptom duration. Pediatrics. 2013; 132 1: 8– 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. . Thomas DG, Apps JN, Hoffmann RG, McCrea M, Hammeke T. Benefits of strict rest after acute concussion: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015; 135 2: 213– 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. . Popoli DM, Burns TG, Meehan W, III, et al. CHOA concussion consensus establishing a uniform policy for academic accommodations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014; 53 3: 217– 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. . Arbogast KB, McGinley AD, Master CL, et al. Cognitive rest and school-based recommendations following pediatric concussion: the need for primary care support tools. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013; 52 5: 397– 402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. . Zonfrillo MR, Master CL, Grady MF, et al. Pediatric providers' self-reported knowledge, practices, and attitudes about concussion. Pediatrics. 2012; 130 6: 1120– 1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. . Student-to-school nurse improvement bill. National Association of School Nurses Web site. http://www.nasn.org/PolicyAdvocacy/StudenttoSchoolNurseRatioImprovementAct. Published 2013. Accessed July 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. . Wing R, Amanullah S, Jacobs E, Clark MA, Merritt C. Heads up: communication is key in school nurses' preparedness for facilitating “return to learn” following concussion. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016; 55 3: 228– 235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. . Williams RM, Welch CE, Weber ML, Parsons JT. Valovich McLeod TC. Athletic trainers' management practices and referral patterns for adolescent athletes after sport-related concussion. Sports Health. 2014; 6 5: 434– 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. . Adams WM, Mazerolle SM, Casa DJ, Huggins RA, Burton L. The secondary school football coach's relationship with the athletic trainer and perspectives on exertional heat stroke. J Athl Train. 2014; 49 4: 469– 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. . Mensch J, Crews C, Mitchell M. Competing perspectives during organizational socialization on the role of certified athletic trainers in high school settings. J Athl Train. 2005; 40 4: 333– 340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]