Abstract

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) constitute two key cellular signalling systems that participate in the modulation of diverse cellular functions. Importantly, growing evidence suggests that cross-talk between these two prominent signalling systems acts to modulate functionality of the ECS as well as redox homeostasis in different cell types. Herein, we review and discuss evidence pertaining to ECS-induced regulation of ROS generating and scavenging mechanisms, as well as highlighting emerging work that supports redox modulation of ECS function. Functionally, the studies outlined reveal that interactions between the ECS and ROS signalling systems can be both stimulatory and inhibitory in nature, depending on cell stimulus, the source of ROS species and cell context. Importantly, such cross-talk may act to maintain cell function, whereas abnormalities in either system may propagate and undermine the stability of both systems, thereby contributing to various pathologies associated with their dysregulation.

Keywords: endocannabinoid system, reactive oxygen species, antioxidant, redox homeostasis, oxidative stress, cannabinoid receptor

1. Introduction

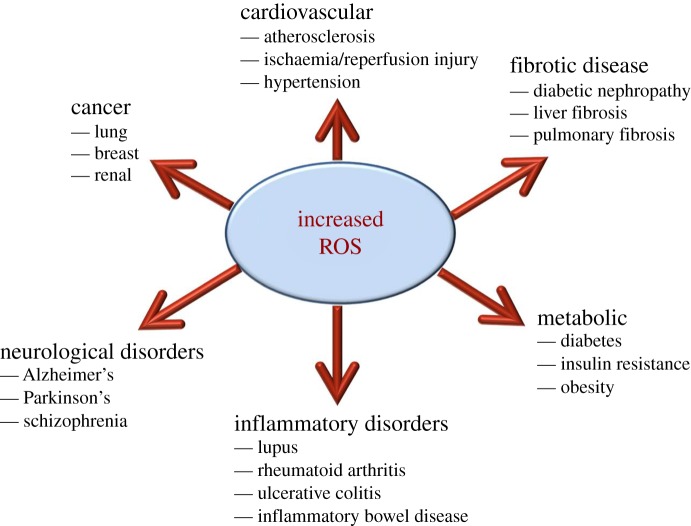

The cellular redox environment constitutes a delicate balance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their removal by antioxidant enzymes and small-molecular-weight antioxidants. At low concentrations, ROS are involved in regulating numerous physiological events, including their ability to mediate signal transduction from membrane receptors, thereby facilitating the activation of multiple proteins and enzymes [1,2]. However, excess accumulation of intracellular ROS causes oxidative stress, which can damage cellular membranes, promote mitochondrial injury and induce cell death, thereby negatively impacting upon cell function and survival [3–5]. Notably, this is largely owing to the damaging effects that free radicals convey upon cellular lipids, proteins and DNA, thus impairing their normal function. Accordingly, the dysregulation of redox homeostasis has been linked with the development of various pathologies, including those associated with metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, cardiovascular disease, as well as various neurodegenerative disorders (e.g. Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis; figure 1) [6–11]. Consequently, there is growing interest in identifying cellular pathways and/or processes that can regulate ROS levels, for example by altering the balance between pro-oxidants and free radical scavenging molecules. In this review, we explore experimental evidence supporting a role for the endocannabinoid system (ECS) in the modulation of redox homeostasis and provide examples of how this relationship may impact upon cellular function.

Figure 1.

ROS involvement in disease pathogenesis. Schematic of the involvement of increased ROS production in the development of various pathologies.

2. Reactive oxygen species: generation and neutralization

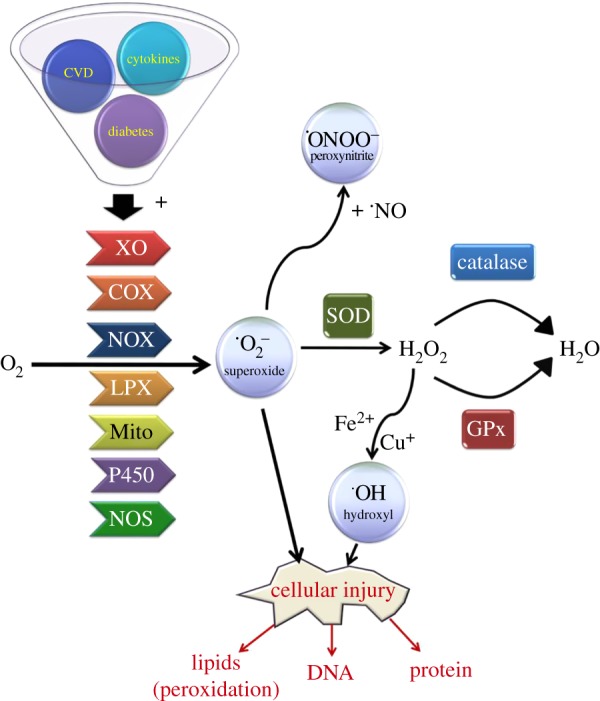

ROS are oxygen-containing molecules that are highly reactive in redox reactions, and are primarily produced by two metabolic sources: the mitochondrial electron-transport chain, and/or through oxygen-metabolizing enzymatic reactions such as those catalysed by xanthine oxidases, the cytochrome P450 system, NADPH oxidases, myeloperoxidase, lipoxygenase and nitric oxide synthase [12–16] (figure 2). Oxygen concentrations can also act as a key determinant of ROS production. Indeed, molecular oxygen is the terminal electron acceptor during energy production whereby it accepts an additional electron to create superoxide (.O2−), a highly reactive form of oxygen. Notably, the superoxide anion can act as a precursor for the formation of other ROS moieties including peroxynitrite (ONOO−), and hydroxyl radicals (.OH) through its reaction with transition metals (e.g. cuprous and ferrous ions; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of pathways involved in ROS production and clearance. Pathological conditions such as chronic inflammation, cardiovascular disease (CVD), as well as obesity and diabetes can lead to the aberrant production of various oxygen radicals from molecular oxygen, including superoxide (O2−), peroxides and hydroxyl radicals. A number of different enzymes have been implicated in mediating this process including NADPH oxidase (NOX), xanthine oxidase (XO), cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LPX), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and cytochrome P450 isoforms as well as ROS derived from mitochondria (Mito). In response, cells will often initiate an antioxidant response that facilitates the neutralization of ROS into less harmful products by activating enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase, in an attempt to alleviate the damaging effects of ROS upon lipid, protein and DNA integrity.

Importantly, there is substantial evidence supporting a role for ROS as key signalling intermediates that can regulate numerous cellular processes, including cell growth and proliferation, by modulating a number of different protein kinases and ion channels [10,17–20]. Cellular ROS levels are maintained by controlling the production and neutralization of ROS by various antioxidant enzymes and small-molecular-weight antioxidants. For example, superoxide is converted to hydrogen peroxide by members of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) family of enzymes, including manganese-dependent SOD (MnSOD), copper/zinc-dependent SOD (CuZnSOD) and extracellular SOD (EcSOD). MnSOD is a mitochondrial enzyme that functions to neutralize ROS generated by these organelles [21]. In contrast, CuZnSOD resides within both the cytoplasm and nucleus, while EcSOD is present in the plasma membrane and extracellular space [22]. Two other key antioxidant enzymes include catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which act to neutralize H2O2 by catalysing its conversion to water. Different isozymes of GPx are present in most subcellular compartments, and function to convert reduced monomeric glutathione (GSH; γ-l-glutamyl-l-cysteinyl-glycine) into its oxidized form (GSSG; glutathione disulfide) using hydrogen peroxide as a substrate, whereas catalase is found primarily in peroxisomes [23–25]. In the case of glutathione, its cysteine residue forms a redox-active thiol group which becomes oxidized when GSH reduces target molecules [26]. Additional intracellular small-molecular-weight antioxidants include cysteine, vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and vitamin E (α-tocopherol). Alternatively, chemical antioxidants such as N-acetyl-l-cysteine are also widely used as ROS scavengers.

3. The endocannabinoid system

The ECS is a ubiquitous ligand-directed signalling system that has been implicated in regulating a wide range of physiological processes and pathologies, including energy homeostasis, cardiovascular disease, cancer and neurodegeneration [27–30]. Two key lipid-derived molecules that act as endogenous ligands for this system are anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA)) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)—commonly referred to as endocannabinoids. Both AEA and 2-AG can be synthesized on demand within the plasma membrane from arachidonic acid-derived lipids [31,32]. Anandamide generation from its membrane phospholipid precursor N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE) is driven by the action of the enzyme NAPE-hydrolysing phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) [33]. In contrast, phospholipase C-mediated cleavage of membrane phosphatidylinositols gives rise to a diacylglycerol precursor whose subsequent hydrolysis (via diacylglycerol lipase activity) permits the formation of 2-AG [34]. In addition to these synthetic pathways, enzymes that catalyse the degradation of anandamide and 2-AG have also been characterized, including fatty acid amide hydroxylase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), respectively [35].

Both AEA and 2-AG evoke cellular and physiological responses through binding and activating two distinct G protein-coupled receptors identified as the cannabinoid type 1 (CB1R) and type 2 (CB2R) receptors [36–39]. Indeed, various synthetic CB1R and/or CB2R agonists (e.g. CP-55,940, ACEA, WIN-55,212-2, JWH-133 and HU-210) have been used to provide mechanistic insight into the regulation of cellular processes by the ECS (table 1) [40,46,47,50,51]. Importantly, these are often applied in combination with selective receptor antagonists to determine receptor-specific responses. Such cannabinoid receptor blockers act either by competitively binding and preventing activation of a receptor by an agonist (i.e. as an antagonist), and/or function as inverse agonists through suppressing spontaneous (ligand-free) receptor signalling. For example, SR141716 (also known as rimonabant) has been shown to act as both a CB1R antagonist and an inverse agonist (table 1) [52,53]. Notably, endocannabinoids have also been reported to mediate some of their biological effects through alternative molecular targets such as the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR55, the transient receptor potential cation channel (TRPV1), as well as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and gamma isoforms [54–56].

Table 1.

Synthetic modulators of cannabinoid receptor function. Citations refer to studies performed using the compounds listed in order to elucidate the functional role of CB1R and CB2R.

| name | activity at CB1 (Ki in nM) | activity at CB2 (Ki in nM) | comments | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEA | 1.4 ± 0.3 | >2000 | selective CB1 receptor agonist | [40,41] |

| AM251 | 7.5 | 2000–3000 | selective CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist | [42,43] |

| SR141716 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | — | selective CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist | [44] |

| JWH-133 | 680 | 3.4 | selective CB2 receptor agonist | [45] |

| AM630 | 5.2 × 103 | 31.2 | selective CB2 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist | [46] |

| CP-55940 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | non-selective potent CB1/2 receptor agonist | [47] |

| HU-210 | 0.1–0.7 | 0.2–0.5 | non-selective potent CB1/2 receptor agonist | [48] |

| WIN-55,212-2 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 0.25 | non-selective CB1/2 receptor agonist | [49] |

4. Endocannabinoid system-mediated regulation of reactive oxygen species

There is accumulating evidence that supports a key role for the ECS in the modulation of ROS production in different cell types. For example, extensive work carried out investigating the neuroprotective properties of cannabinoid ligands has revealed a crucial link between the ECS and redox homeostasis [57–60]. For example, anandamide has been reported to attenuate neurotoxicity in response to oxidative stress [58,61]. In accord with this, the mixed CB1R/CB2R agonist WIN-55,212-2 and the plant-derived cannabinoid tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) have both been shown to protect serum-deprived astrocytes against H2O2-induced apoptosis [57]. Notably, this protective action was found to be prevented by the selective CB1R blocker SR141716, suggesting the involvement of CB1R in mediating these anti-apoptotic and/or antioxidant actions. However, it is noteworthy that the protective effect of THC may be cell specific as judged by the finding that activation of CB1R by THC increases cellular susceptibility of C6 glioblastoma cells to oxidative damage [62].

Notably, as well as responses mediated through CB1R, there is evidence to suggest that stimulation of CB2R may also convey beneficial free radical scavenging effects. Indeed, in a study by Ribeiro et al. [60], and co-workers, the selective CB2R agonist AM1241 was shown to almost completely block ROS generation in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in BV-2 cells. Consistent with this, CB2R activation has also been reported to attenuate oxidative stress damage in various tissue types, including brain [59], kidney [63], heart [64] and liver [65]. Moreover, previous work using CB2R agonists and/or knockout mice indicates that activation of CB2R confers protection against hepatic ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury, concomitant with its ability to alleviate tissue free radical damage [66–68]. Allied to this, further evidence supporting a protective role for the ECS was provided in a study by Cao et al. [65], who demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase, the enzyme which catalyses the hydrolysis of 2-AG, led to the suppression of oxidative stress and associated inflammation in liver tissue following hepatic I/R injury in mice [65]. Notably, the protective effects of MAGL inhibition against hepatic I/R injury involved increased endocannabinoid signalling via CB2R [65].

Conversely, stimulation of the ECS has also been demonstrated to induce the production of ROS in certain cell types [69–71]. For example, 2-AG stimulation has been shown to promote an increase in cellular ROS in BeWo trophoblasts [71]. Moreover, increased ROS and concomitant TNF-α cytokine production have been reported in human macrophages following CB1R activation, with both responses being attenuated by pharmacological inhibition of CB1R [69]. Moreover, CB1R inhibition using SR141716 has been found to ameliorate diabetes-induced retinal oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as improving oxidative stress in mice with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [72]. In accord with this, evidence from a number of studies indicates that CB1R stimulation can either promote and/or facilitate oxidative stress and associated inflammation and/or cell death in human coronary artery endothelial cells [70], as well as in various models of cardiomyopathy [28,73,74], and nephropathy [75]. In addition, work by Dando et al. [76] showed that activation of CB1R or CB2R promotes oxidative stress in Panc1 pancreatic cancer cells resulting in the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent induction of autophagy, which may, at least in part, account for the observed inhibitory effects of cannabinoid receptor ligands upon tumour cell growth [77–79]. Importantly, such findings are often supported by data demonstrating the beneficial effects on ROS-related inflammation and/or cell death following genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of CB1R [72,74,75,77,78].

Intriguingly, CB1R and CB2R have also been reported to differentially regulate ROS production within the same cell type. For example, a study by Han et al. [69] demonstrated that CB1R activation led to the upregulation of ROS levels in RAW264.7 macrophages, whereas CB2R stimulation in the same cells acted to suppress CB1R-stimulated ROS production through a pathway involving the small G protein Rap1. Therefore, modulation of these distinct cannabinoid receptors can promote differential responses with respect to cellular redox homeostasis, even within one specific cell type.

4.1. Mechanisms underlying cellular reactive oxygen species production by the endocannabinoid system

It is likely that the ability of the ECS to modulate the production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species is largely mediated through alterations in the expression and/or activity of enzymes implicated in the generation of these free radical species. For example, the NADPH oxidase (Nox) family of proteins are key generators of cellular ROS, particularly in central nervous system cell types such as neurons, astrocytes and microglia under pathophysiological conditions [80,81]. Notably, treatment of H2O2-stimulated HT22 neuronal cells with AEA led to the suppression of intracellular ROS and Nox2 protein/mRNA expression, with these antioxidant responses being reversed by application of the CB1R antagonist AM251 or CB1R-siRNA [82]. The authors of the same study also demonstrated that under conditions of oxidative stress, AEA acted to raise intracellular levels of SOD and GSH, while concomitantly decreasing GSSG. Importantly, these responses were prevented by AM251, indicating that AEA could restore the balance of intracellular antioxidants and pro-oxidants through targeting CB1R. In accord with these findings, treatment of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats with Δ9-THC was also reported to increase pancreatic glutathione levels, as well as enzymatic activities of SOD and catalase [83]. Conversely, in other cell types, CB1R inhibition (by either pharmacological or genetic silencing) has been shown to attenuate ROS formation by repressing the expression of Nox isoforms [28,74,75,84]. Therefore, these findings suggest that the pathways involved in mediating the effects of cannabinoid receptor modulation upon ROS formation may be cell-type-specific. Notably, both CB1R and CB2R agonists have also been reported to repress the expression/activity of cyclooxygenase, an enzyme implicated not only in the generation of ROS but also in the degradation of anandamide [85–87].

Alternatively, the ability of ECS stimulation to regulate the production of cellular ROS may be mediated through the accumulation of toxic lipid intermediates. For example, activation of CB1R and/or CB2R has been associated with increased ceramide formation in various cell types (e.g. hepatocytes, colon cancer cells) through either increased sphingomyelin hydrolysis or ceramide de novo synthesis [88–90]. This is in accord with the reported ability of ceramide to stimulate activation of NADPH oxidase by promoting translocation of its regulatory p47phox subunit to the plasma membrane [91]. Conversely, chronic CB1R stimulation has also been reported to protect against the sensitizing effects of ceramide towards H2O2-induced loss of astrocyte viability [57]. Therefore, some of the biological actions of cannabinoid receptor modulation, for example the maintenance of cell viability, may occur partly as a result of ECS modulation of ceramide and ROS formation [92].

In addition, various protein kinases may also be implicated in mediating ECS regulation of ROS. One such candidate is the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), whose regulation of ROS production has been described in several systems, including leptin-stimulated endothelial cells [93], tumour necrosis factor-treated fibrosarcoma cells [94], and in cardiomyocytes following hypoxia and reoxygenation [95]. Given the fact that PKA has been implicated in positively regulating the expression and/or activity of enzymes involved in ROS generation such as NADPH oxidase and nNOS [96,97], and that activation of CB1R can lead to reduced cellular levels of cyclic AMP and the corresponding inhibition of PKA [98], this may, at least in part, act as a means by which CB1R stimulation acts to suppress ROS formation in certain cell types, such as neuronal cells [61].

Protein kinase C (PKC) activity may also be involved in mediating the pro- and/or antioxidant responses induced by ECS stimulation. Indeed, various PKC isoforms have been shown to convey biological actions of cannabinoid ligands [99–101]. Moreover, PKC has been reported to disrupt cannabinoid actions through its ability to serine phosphorylate the CB1 receptor [102]. Based on previous findings that PKC isoforms (e.g. PKCα and PKCε) can facilitate and/or stimulate ROS formation, for example through activation of NADPH oxidase [103,104], it is plausible that ECS-mediated regulation of ROS homeostasis may also be mediated, at least in part, through the activity of one or more PKC isoforms, although further work will be required to determine their involvement. In addition, active PKC can stimulate the MEK/ERK1/2 signalling pathway whose activation has been shown to upregulate Nox5 activity [105], as well as being positively modulated by CB1R and/or CB2R activity [30,106–108]. Furthermore, stimulation of RAW264.7 cells by the CB1R agonist ACEA was found to induce ROS generation by a pathway dependent upon p38 MAPK, a protein kinase which can also be stimulated in response to PKC activity [69,109].

Another potential regulator of ROS production by the ECS is Rap1, a small G protein of the Ras family. In a study by Han et al. [69], active Rap1 was demonstrated to inhibit CB1R-induced generation of intracellular ROS and associated pro-inflammatory responses in murine peritoneal macrophages. Moreover, expression of a dominant-negative form of Rap1 profoundly enhanced CB1R-dependent ROS production. Intriguingly, the authors of the same study also demonstrated that CB2R stimulation led to the activation of Rap1, concomitant with the amelioration of CB1R-induced ROS formation in macrophages [69]. These findings therefore highlight the potential opposing effects of CB1R and CB2R activation in the modulation of ROS production in macrophages, and implicate a key role for Rap1 in regulating ROS levels by the ECS in immune cells.

In addition, the ECS has also been reported to regulate the activity of redox-sensitive transcription factors. For example, CB2R-mediated protection against myocardial infarction in mice was shown to coincide with increased nuclear translocation of the transcription factor Nrf-2 in the myocardium, concomitant with the induction of its target gene haem oxygenase-1, a key cellular antioxidant [110]. Notably, Nrf-2 functions to activate the antioxidant response element transcriptional pathway, thereby controlling the expression of genes whose protein products are involved in the detoxification and elimination of reactive oxygen intermediates [111].

Alternatively, cannabinoid ligands may act to alter cellular ROS production through controlling the production of mitochondrial-derived ROS. For example, in hepatic stellate cells, mitochondria were found to be the predominant source of ROS generated in response to 2-AG stimulation [112]. Furthermore, a recent study by Ma et al. [113] demonstrated that treating hippocampal neurons and tissue with the CB1R agonist ACEA increased the expression of CB1R protein in the mitochondrial membrane. Notably, in this same study, ACEA was shown to inhibit ROS generation and attenuate Ca2+-induced mitochondrial injury, effects that were prevented by co-application of a cell permeant CB1R antagonist (AM251), but not following co-treatment with a cell impermeable CB1R blocker (haemopressin). Therefore, it is possible that CB1R residing within mitochondria may act to control the production of ROS by these organelles, for example, by altering the expression and/or activity of components of the mitochondrial electron-transport chain, and/or by promoting changes in mitochondrial membrane potential.

4.2. CB1R/CB2R-independent modulation of cellular reactive oxygen species production

As well as conveying their biological effects through activation of CB1R and/or CB2R, it is possible that endocannabinoids may also regulate ROS levels by targeting alternative receptors/ion channels such as TRPV1 or GPR55 [55,56]. Indeed, one study performed by Balenga et al. [114] revealed that 2-AG-induced ROS production in neutrophils was significantly diminished upon co-treatment with the GPR55 activator lysophosphatylinositol (LPI). Endocannabinoids such as AEA are also known to mediate some of their cellular responses by targeting the non-selective cation channel TRPV1, whose activation has been linked to increased ROS production [115–118]. Indeed, this may be driven, at least in part, through the ability of TRPV1 stimulation to trigger Ca2+ signalling which is functionally coupled to ROS generating systems, in particular mitochondrial ROS production, as well as the upregulation of Nox5 activity following its phosphorylation by CAMKII, a serine/threonine protein kinase activated in response to calcium signals [119–121]. In addition, AEA has also been reported to target the PPAR family of nuclear receptors [54], whose activation is known to induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes, including catalase and glutathione peroxidase 3 [122,123].

It should be highlighted that some cannabinoid receptor ligands may also convey more direct free radical scavenging activity. For example, analysis performed in cell-free biochemical assays has revealed that some phenolic cannabinoid compounds (e.g. Δ9-THC, cannabinol, cannabidiol, CP-55,940, HU-210 and AM-404) can act as potent lipophilic antioxidants [124]. Moreover, owing to their lipophilicity, these compounds may further affect membrane-associated and intracellular signalling mechanisms, leading to changes in the activity of membrane-bound receptor systems (e.g. neurotransmitter receptors). Therefore, such free radical scavenging activity should also be considered as a potential explanation for non-CB1R/CB2R-dependent modes of antioxidant action by cannabinoid receptor ligands.

5. Redox-mediated regulation of the endocannabinoid system

In addition to the effects of altering ECS activity upon cellular redox homeostasis, it should be highlighted that changes in cellular redox homeostasis can also impact upon the function of the ECS. For example, activation of NADPH oxidase isoforms Nox4 and Nox1 has been reported to mediate the upregulation of CB1R expression in mouse hepatic stellate cells during Schistosoma J. infection [125]. Consistent with this finding, H2O2-induced oxidative stress has been reported to increase CB1R and CB2R mRNA and protein abundance in human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, as well as downregulating expression of FAAH, the enzyme involved in the degradation of anandamide [126]. The authors of the same study also demonstrated that treatment with the CB2R agonist JWH-015 protected RPE cells from oxidative damage, suggesting that upregulation of cannabinoid receptor expression and/or endocannabinoid levels may constitute part of a counter-feedback mechanism to ameliorate the damaging effects of ROS exposure under those conditions. Furthermore, Batkai et al. [66] have reported elevated hepatic levels of AEA and 2-AG following I/R injury in mice. Notably, the authors of the same study also demonstrated raised levels of these endocannabinoids in hepatocytes following brief exposure to pro-oxidants (hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite). Therefore, these findings support an important role for ROS in modulating ECS function, for example by regulating the expression of key ECS components.

6. Conclusion and future perspective

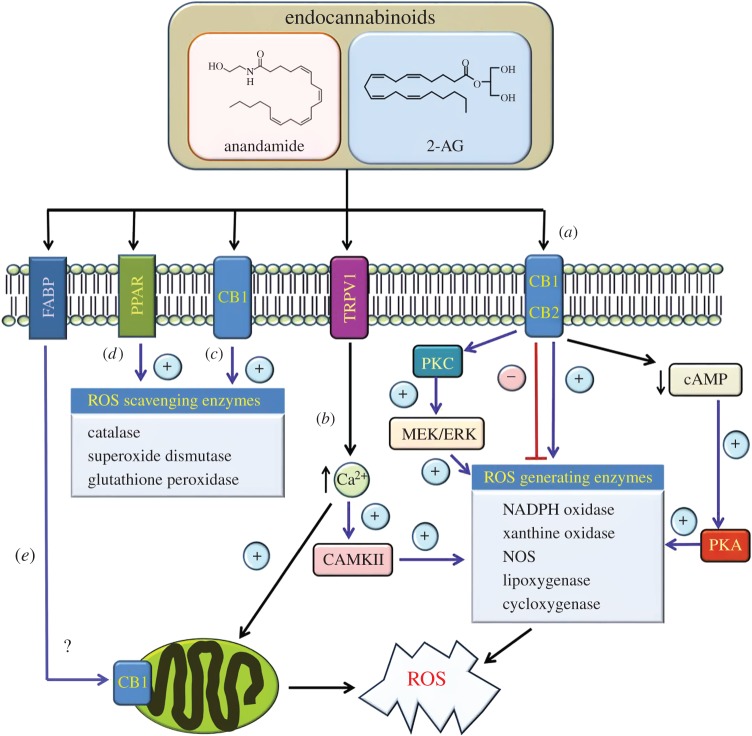

To conclude, there is growing appreciation that the ECS may play an important role in the regulation of cellular redox homeostasis. Collectively, the evidence presented in this review indicates that ECS activation or inhibition can convey detrimental and/or beneficial biological effects through altering cellular ROS levels, depending on the cell type and/or stimulus involved. Indeed, the studies highlighted in this review show that ECS function can impact upon free radical production in a number of different ways (figure 3). Crucially, given the importance of redox status in the development of numerous pathologies, these findings identify ECS components as potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of oxidative stress-related neurological, cardiovascular and metabolic disorders.

Figure 3.

Summary of pathways implicated in the regulation of ROS production by the ECS. (a) Activation of CB1R and/or CB2R has been reported to either stimulate and/or repress the activity of enzymes implicated in ROS generation as indicated. For example, cannabinoid receptor activation may act to suppress cAMP-dependent activation of PKA thereby repressing the expression and/or activity of enzymes such as NADPH oxidase. Alternatively, cannabinoid receptor stimulation can activate PKC isoforms and the downstream MEK/ERK signalling axis which have been implicated in upregulating NADPH oxidase activity. (b) Endocannabinoids such as anandamide have also been shown to target the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. In this case, TRPV1 activation would promote an increase in intracellular calcium signalling which in turn may impact on the expression/activity of ROS generating enzymes, for example through stimulating CAMKII activity. In addition, elevated calcium levels may also promote an increase in ROS generation within mitochondria. (c,d) Endocannabinoids such as anandamide may also convey protective effects by inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase through activation of CB1R or PPAR receptors. (e) Following its uptake into cells, for example via transporters such as fatty acid binding protein (FABP) isoforms, endocannabinoids such as anandamide may also directly impact upon mitochondrial ROS generation through targeting CB1R residing within these organelles.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Research in the authors' laboratory is supported by Diabetes UK and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

References

- 1.Griendling KK, Ushio-Fukai M. 2000. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiotensin II signaling. Regul. Pept 91, 21–27. (doi:10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00136-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Droge W. 2002. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 47–95. (doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valencia A, Moran J. 2001. Role of oxidative stress in the apoptotic cell death of cultured cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 64, 284–297. (doi:10.1002/jnr.1077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ha JS, Lim HM, Park SS. 2010. Extracellular hydrogen peroxide contributes to oxidative glutamate toxicity. Brain Res. 1359, 291–297. (doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.086) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu X, Xu H, Sun B, Zhu Z, Zheng D, Li X. 2013. Enhanced neuroprotective effects of resveratrol delivered by nanoparticles on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in rat cortical cell culture. Mol. Pharm. 10, 2045–2053. (doi:10.1021/mp400056c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonian NA, Coyle JT. 1996. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 36, 83–106. (doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.000503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castilho RF, Ward MW, Nicholls DG. 1999. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 72, 1394–1401. (doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721394.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markesbery WR, Carney JM. 1999. Oxidative alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 9, 133–146. (doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00215.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhalla NS, Temsah RM, Netticadan T. 2000. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J. Hypertens. 18, 655–673. (doi:10.1097/00004872-200018060-00002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. 2007. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 44–84. (doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao ZY, Luan P, Huang SX, Xiao SH, Zhao J, Zhang B, Gu BB, Pi RB, Liu J. 2013. Edaravone protects HT22 neurons from H2O2-induced apoptosis by inhibiting the MAPK signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 19, 163–169. (doi:10.1111/cns.12044) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massey V, Strickland S, Mayhew SG, Howell LG, Engel PC, Matthews RG, Schuman M, Sullivan PA. 1969. The production of superoxide anion radicals in the reaction of reduced flavins and flavoproteins with molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 36, 891–897. (doi:10.1016/0006-291X(69)90287-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinzel B, John M, Klatt P, Bohme E, Mayer B. 1992. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent formation of hydrogen peroxide by brain nitric oxide synthase. Biochem. J. 281, 627–630. (doi:10.1042/bj2810627) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bokoch GM, Knaus UG. 2003. NADPH oxidases: not just for leukocytes anymore! Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 502–508. (doi:10.1016/s0968-0004(03)00194-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zangar RC, Davydov DR, Verma S. 2004. Mechanisms that regulate production of reactive oxygen species by cytochrome P450. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 199, 316–331. (doi:10.1016/j.taap.2004.01.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebanoff SJ. 2005. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77, 598–625. (doi:10.1189/jlb.1204697) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burdon RH. 1995. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18, 775–794. (doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00198-S) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behrend L, Henderson G, Zwacka RM. 2003. Reactive oxygen species in oncogenic transformation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1441–1444. (doi:10.1042/bst0311441) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. 2006. Redox signaling in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 71, 247–258. (doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartosz G. 2009. Reactive oxygen species: destroyers or messengers? Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 1303–1315. (doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCord JM, Fridovich I. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folz RJ, Crapo JD. 1994. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3): tissue-specific expression, genomic characterization, and computer-assisted sequence analysis of the human EC SOD gene. Genomics 22, 162–171. (doi:10.1006/geno.1994.1357) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto K, Volkl A, Hashimoto T, Fahimi HD. 1988. Catalase in guinea pig hepatocytes is localized in cytoplasm, nuclear matrix and peroxisomes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 46, 129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberley TD, Oberley LW, Slattery AF, Lauchner LJ, Elwell JH. 1990. Immunohistochemical localization of antioxidant enzymes in adult Syrian hamster tissues and during kidney development. Am. J. Pathol. 137, 199–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brigelius-Flohe R, Maiorino M. 2013. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830, 3289–3303. (doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. 2010. Orchestrating redox signaling networks through regulatory cysteine switches. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 47–62. (doi:10.1021/cb900258z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Marzo V, Petrocellis LD. 2006. Plant, synthetic, and endogenous cannabinoids in medicine. Annu. Rev. Med. 57, 553–574. (doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.011205.135648) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhopadhyay P, et al. 2010. CB1 cannabinoid receptors promote oxidative stress and cell death in murine models of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy and in human cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 773–784. (doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp369) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugamura K, et al. 2010. Cannabinoid 1 receptor blockade reduces atherosclerosis with enhances reverse cholesterol transport. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 17, 141–147. (doi:10.5551/jat.2865) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Fang Y, Chen T, Guo J, Yan J, Song S, Zhang L, Liao H. 2013. WIN55, 212-2 promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and improve remyelination through regulation of the phosphorylation level of the ERK 1/2 via cannabinoid receptor 1 after stroke-induced demyelination. Brain Res. 1491, 225–235. (doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basavarajappa BS. 2007. Neuropharmacology of the endocannabinoid signaling system: molecular mechanisms, biological actions and synaptic plasticity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 5, 81–97. (doi:10.2174/157015907780866910) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alger BE, Kim J. 2011. Supply and demand for endocannabinoids. Trends Neurosci. 34, 304–315. (doi:10.1016/j.tins.2011.03.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N. 2004. Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5298–5305. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M306642200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ueda N, Tsuboi K, Uyama T, Ohnishi T. 2011. Biosynthesis and degradation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. BioFactors (Oxford, England) 37, 1–7. (doi:10.1002/biof.131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taschler U, et al. 2011. Monoglyceride lipase deficiency in mice impairs lipolysis and attenuates diet-induced insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17 467–17 477. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.215434) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devane WA, Dysarz FA III, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. 1988. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 34, 605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. 1990. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346, 561–564. (doi:10.1038/346561a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cencioni MT, Chiurchiu V, Catanzaro G, Borsellino G, Bernardi G, Battistini L, Maccarrone M. 2010. Anandamide suppresses proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via CB2 receptors. PLoS ONE 5, e8688 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008688) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desroches J, Charron S, Bouchard JF, Beaulieu P. 2013. Endocannabinoids decrease neuropathic pain-related behavior in mice through the activation of one or both peripheral CB1 and CB2 receptors. Neuropharmacology 77, 441–452. (doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipina C, Stretton C, Hastings S, Hundal JS, Mackie K, Irving AJ, Hundal HS. 2010. Regulation of MAP kinase-directed mitogenic and protein kinase B-mediated signaling by cannabinoid receptor type 1 in skeletal muscle cells. Diabetes 59, 375–385. (doi:10.2337/db09-0979) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Tedesco L, et al. 2010. Cannabinoid receptor stimulation impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse white adipose tissue, muscle, and liver: the role of eNOS, p38 MAPK, and AMPK pathways. Diabetes 59, 2826–2836. (doi:10.2337/db09-1881) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jbilo O, et al. 2005. The CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant reverses the diet-induced obesity phenotype through the regulation of lipolysis and energy balance. FASEB J. 19, 1567–1569. (doi:10.1096/fj.04-3177fje) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eckardt K, et al. 2009. Cannabinoid type 1 receptors in human skeletal muscle cells participate in the negative crosstalk between fat and muscle. Diabetologia 52, 664–674. (doi:10.1007/s00125-008-1240-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang NL, Juang JM, Wang YH, Hsueh CH, Liang YJ, Lin JL, Tsai CT, Lai LP. 2010. Rimonabant inhibits TNF-α-induced endothelial IL-6 secretion via CB1 receptor and cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 31, 1447–1453. (doi:10.1038/aps.2010.126) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Q, Wang F, Zhang YM, Zhou JJ, Zhang Y. 2013. Activation of cannabinoid type 2 receptor by JWH133 protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 31, 693–702. (doi:10.1159/000350088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deveaux V, et al. 2009. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor potentiates obesity-associated inflammation, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. PLoS ONE 4, e5844 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005844) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.South T, Huang XF. 2008. Temporal and site-specific brain alterations in CB1 receptor binding in high fat diet-induced obesity in C57Bl/6 mice. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 1288–1294. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01785.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Athanasiou A, et al. 2007. Cannabinoid receptor agonists are mitochondrial inhibitors: a unified hypothesis of how cannabinoids modulate mitochondrial function and induce cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364, 131–137. (doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gustafsson K, Christensson B, Sander B, Flygare J. 2006. Cannabinoid receptor-mediated apoptosis induced by R(+)-methanandamide and Win55,212-2 is associated with ceramide accumulation and p38 activation in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1612–1620. (doi:10.1124/mol.106.025981) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mechoulam R, et al. 1995. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 50, 83–90. (doi:10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Hare JD, Zielinski E, Cheng B, Scherer T, Buettner C. 2011. Central endocannabinoid signaling regulates hepatic glucose production and systemic lipolysis. Diabetes 60, 1055–1062. (doi:10.2337/db10-0962) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouaboula M, Poinot-Chazel C, Bourrie B, Canat X, Calandra B, Rinaldi-Carmona M, Le Fur G, Casellas P. 1995. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by stimulation of the central cannabinoid receptor CB1. Biochem. J. 312, 637–641. (doi:10.1042/bj3120637) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Landsman RS, Burkey TH, Consroe P, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. 1997. SR141716A is an inverse agonist at the human cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 334, R1–R2. (doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01160-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Sullivan SE. 2007. Cannabinoids go nuclear: evidence for activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 152, 576–582. (doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707423) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyashita K, Oyama T, Sakuta T, Tokuda M, Torii M. 2012. Anandamide induces matrix metalloproteinase-2 production through cannabinoid-1 receptor and transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 in human dental pulp cells in culture. J. Endodont. 38, 786–790. (doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.02.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharir H, Console-Bram L, Mundy C, Popoff SN, Kapur A, Abood ME. 2012. The endocannabinoids anandamide and virodhamine modulate the activity of the candidate cannabinoid receptor GPR55. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7, 856–865. (doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9351-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carracedo A, Geelen MJ, Diez M, Hanada K, Guzman M, Velasco G. 2004. Ceramide sensitizes astrocytes to oxidative stress: protective role of cannabinoids. Biochem. J. 380, 435–440. (doi:10.1042/bj20031714) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mnich K, Finn DP, Dowd E, Gorman AM. 2010. Inhibition by anandamide of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cell death in PC12 cells. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 818497 (doi:10.1155/2010/818497) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aso E, Juves S, Maldonado R, Ferrer I. 2013. CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonist ameliorates Alzheimer-like phenotype in AbetaPP/PS1 mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 35, 847–858. (doi:10.3233/jad-130137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ribeiro R, Wen J, Li S, Zhang Y. 2013. Involvement of ERK1/2, cPLA2 and NF-κB in microglia suppression by cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 100–101, 1–14. (doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2012.11.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim SH, Won SJ, Mao XO, Jin K, Greenberg DA. 2005. Involvement of protein kinase A in cannabinoid receptor-mediated protection from oxidative neuronal injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313, 88–94. (doi:10.1124/jpet.104.079509) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goncharov I, Weiner L, Vogel Z. 2005. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol increases C6 glioma cell death produced by oxidative stress. Neuroscience 134, 567–574. (doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Pan H, Patel V, Mukhopadhyay B, Batkai S, Gao B, Hasko G, Pacher P. 2010. Cannabinoid-2 receptor limits inflammation, oxidative/nitrosative stress, and cell death in nephropathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 457–467. (doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montecucco F, Lenglet S, Braunersreuther V, Burger F, Pelli G, Bertolotto M, Mach F, Steffens S. 2009. CB(2) cannabinoid receptor activation is cardioprotective in a mouse model of ischemia/reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 46, 612–620. (doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.12.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao Z, et al. 2013. Monoacylglycerol lipase controls endocannabinoid and eicosanoid signaling and hepatic injury in mice. Gastroenterology 144, 808–817.e15. (doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.028) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Batkai S, et al. 2007. Cannabinoid-2 receptor mediates protection against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 21, 1788–1800. (doi:10.1096/fj.06-7451com) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pacher P, Hasko G. 2008. Endocannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors in ischaemia–reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 252–262. (doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707582) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pacher P, Mechoulam R. 2011. Is lipid signaling through cannabinoid 2 receptors part of a protective system? Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 193–211. (doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2011.01.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han KH, et al. 2009. CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors differentially regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by macrophages. Cardiovasc. Res. 84, 378–386. (doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp240) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Hasko G, Liaudet L, Mackie K, Pacher P. 2010. Cannabinoid-1 receptor activation induces reactive oxygen species-dependent and -independent mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and cell death in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 688–700. (doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00712.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Costa MA, Fonseca BM, Keating E, Teixeira NA, Correia-da-Silva G. 2014. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol effects in cytotrophoblasts: metabolic enzymes expression and apoptosis in BeWo cells. Reproduction 147, 301–311. (doi:10.1530/rep-13-0563) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jorgacevic B, Mladenovic D, Ninkovic M, Veskovic M, Dragutinovic V, Vatazevic A, Vucevic D, Jesic Vukicevic R, Radosavljevic T. 2015. Rimonabant improves oxidative/nitrosative stress in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 842108 (doi:10.1155/2015/842108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mukhopadhyay P, et al. 2007. Pharmacological inhibition of CB1 cannabinoid receptor protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 528–536. (doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rajesh M, et al. 2012. Cannabinoid 1 receptor promotes cardiac dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 61, 716–727. (doi:10.2337/db11-0477) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mukhopadhyay P, et al. 2010. CB1 cannabinoid receptors promote oxidative/nitrosative stress, inflammation and cell death in a murine nephropathy model. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 657–668. (doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00769.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dando I, Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Dalla Pozza E, D'Alessandro A, Zolla L, Palmieri M. 2013. Cannabinoids inhibit energetic metabolism and induce AMPK-dependent autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 4, e664 (doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.151) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarfaraz S, Afaq F, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. 2005. Cannabinoid receptor as a novel target for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 1635–1641. (doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-3410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qamri Z, Preet A, Nasser MW, Bass CE, Leone G, Barsky SH, Ganju RK. 2009. Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit tumor growth and metastasis of breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8, 3117–3129. (doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-09-0448) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Donadelli M, et al. 2011. Gemcitabine/cannabinoid combination triggers autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 2, e152 (doi:10.1038/cddis.2011.36) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen H, et al. 2011. Oxidative stress in ischemic brain damage: mechanisms of cell death and potential molecular targets for neuroprotection. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1505–1517. (doi:10.1089/ars.2010.3576) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paramo B, Montiel T, Hernandez-Espinosa DR, Rivera-Martinez M, Moran J, Massieu L. 2013. Calpain activation induced by glucose deprivation is mediated by oxidative stress and contributes to neuronal damage. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 2596–2604. (doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.08.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jia J, Ma L, Wu M, Zhang L, Zhang X, Zhai Q, Jiang T, Wang Q, Xiong L. 2014. Anandamide protects HT22 cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide by inhibiting CB1 receptor-mediated type 2 NADPH oxidase. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 893516 (doi:10.1155/2014/893516) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coskun ZM, Bolkent S. 2014. Oxidative stress and cannabinoid receptor expression in type-2 diabetic rat pancreas following treatment with Delta(9)-THC. Cell Biochem. Funct. 32, 612–619. (doi:10.1002/cbf.3058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tiyerili V, Zimmer S, Jung S, Wassmann K, Naehle CP, Lutjohann D, Zimmer A, Nickenig G, Wassmann S. 2010. CB1 receptor inhibition leads to decreased vascular AT1 receptor expression, inhibition of oxidative stress and improved endothelial function. Basic Res. Cardiol. 105, 465–477. (doi:10.1007/s00395-010-0090-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zoppi S, Perez Nievas BG, Madrigal JL, Manzanares J, Leza JC, Garcia-Bueno B. 2011. Regulatory role of cannabinoid receptor 1 in stress-induced excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 805–818. (doi:10.1038/npp.2010.214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim J, Watkins BA. 2014. Cannabinoid receptor antagonists and fatty acids alter endocannabinoid system gene expression and COX activity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 25, 815–823. (doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.03.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zoppi S, Madrigal JL, Caso JR, Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Manzanares J, Leza JC, Garcia-Bueno B. 2014. Regulatory role of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in stress-induced neuroinflammation in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2814–2826. (doi:10.1111/bph.12607) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Velasco G, Galve-Roperh I, Sanchez C, Blazquez C, Haro A, Guzman M. 2005. Cannabinoids and ceramide: two lipids acting hand-by-hand. Life Sci. 77, 1723–1731. (doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cianchi F, et al. 2008. Cannabinoid receptor activation induces apoptosis through tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated ceramide de novo synthesis in colon cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 7691–7700. (doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-08-0799) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cinar R, Godlewski G, Liu J, Tam J, Jourdan T, Mukhopadhyay B, Harvey-White J, Kunos G. 2014. Hepatic cannabinoid-1 receptors mediate diet-induced insulin resistance by increasing de novo synthesis of long-chain ceramides. Hepatology 59, 143–153. (doi:10.1002/hep.26606) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang DX, Zou AP, Li PL. 2003. Ceramide-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and endothelial dysfunction in small coronary arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 284, H605–H612. (doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen YY, Hsu MJ, Sheu JR, Lee LW, Hsieh CY. 2013. Andrographolide, a novel NF-κB inhibitor, induces vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis via a ceramide-p47phox-ROS signaling cascade. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 821813 (doi:10.1155/2013/821813) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yamagishi SI, Edelstein D, Du XL, Kaneda Y, Guzman M, Brownlee M. 2001. Leptin induces mitochondrial superoxide production and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic endothelial cells by increasing fatty acid oxidation via protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25 096–25 100. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M007383200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Van Herreweghe F, Mao J, Chaplen FW, Grooten J, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Vancompernolle K. 2002. Tumor necrosis factor-induced modulation of glyoxalase I activities through phosphorylation by PKA results in cell death and is accompanied by the formation of a specific methylglyoxal-derived AGE. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 949–954. (doi:10.1073/pnas.012432399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El Jamali A, Freund C, Rechner C, Scheidereit C, Dietz R, Bergmann MW. 2004. Reoxygenation after severe hypoxia induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro: activation of CREB downstream of GSK3β. FASEB J. 18, 1096–1098. (doi:10.1096/fj.03-1054fje) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boissel JP, Bros M, Schrock A, Godtel-Armbrust U, Forstermann U. 2004. Cyclic AMP-mediated upregulation of the expression of neuronal NO synthase in human A673 neuroepithelioma cells results in a decrease in the level of bioactive NO production: analysis of the signaling mechanisms that are involved. Biochemistry 43, 7197–7206. (doi:10.1021/bi0302191) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Savchenko VL. 2013. Regulation of NADPH oxidase gene expression with PKA and cytokine IL-4 in neurons and microglia. Neurotox. Res. 23, 201–213. (doi:10.1007/s12640-012-9327-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Childers SR, Deadwyler SA. 1996. Role of cyclic AMP in the actions of cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 52, 819–827. (doi:10.1016/0006-2952(96)00419-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Asimaki O, Mangoura D. 2011. Cannabinoid receptor 1 induces a biphasic ERK activation via multiprotein signaling complex formation of proximal kinases PKCepsilon, Src, and Fyn in primary neurons. Neurochem. Int. 58, 135–144. (doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2010.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang W, Cao X, Liu C, Liu L. 2012. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 inhibits TRPV1 in trigeminal ganglion neurons via PKA and PKC pathways. Neurol. Sci. 33, 79–85. (doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0620-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ma L, Jia J, Liu X, Bai F, Wang Q, Xiong L. 2015. Activation of murine microglial N9 cells is attenuated through cannabinoid receptor CB2 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 92–97. (doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Garcia DE, Brown S, Hille B, Mackie K. 1998. Protein kinase C disrupts cannabinoid actions by phosphorylation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J. Neurosci. 18, 2834–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lv P, et al. 2012. Phosphorylation of smooth muscle 22alpha facilitates angiotensin II-induced ROS production via activation of the PKCdelta-P47phox axis through release of PKCdelta and actin dynamics and is associated with hypertrophy and hyperplasia of vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo. Circ. Res. 111, 697–707. (doi:10.1161/circresaha.112.272013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen F, Yu Y, Haigh S, Johnson J, Lucas R, Stepp DW, Fulton DJ. 2014. Regulation of NADPH oxidase 5 by protein kinase C isoforms. PLoS ONE 9, e88405 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pandey D, Fulton DJ. 2011. Molecular regulation of NADPH oxidase 5 via the MAPK pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H1336–H1344. (doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01163.2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ahn KH, Mahmoud MM, Kendall DA. 2012. Allosteric modulator ORG27569 induces CB1 cannabinoid receptor high affinity agonist binding state, receptor internalization, and Gi protein-independent ERK1/2 kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12 070–12 082. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.316463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Franklin JM, Carrasco GA. 2013. Cannabinoid receptor agonists upregulate and enhance serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor activity via ERK1/2 signaling. Synapse 67, 145–159. (doi:10.1002/syn.21626) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vida M, et al. 2014. CB1 blockade potentiates down-regulation of lipogenic gene expression in perirenal adipose tissue in high carbohydrate diet-induced obesity. PLoS ONE 9, e90016 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tanaka Y, Gavrielides MV, Mitsuuchi Y, Fujii T, Kazanietz MG. 2003. Protein kinase C promotes apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through activation of p38 MAPK and inhibition of the Akt survival pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33 753–33 762. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M303313200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang Y, et al. 2014. Effects of cannabinoid receptor type 2 on endogenous myocardial regeneration by activating cardiac progenitor cells in mouse infarcted heart. Sci. China Life Sci. 57, 201–208. (doi:10.1007/s11427-013-4604-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB. 2009. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13 291–13 295. (doi:10.1074/jbc.R900010200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Siegmund SV, Qian T, de Minicis S, Harvey-White J, Kunos G, Vinod KY, Hungund B, Schwabe RF. 2007. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl glycerol induces death of hepatic stellate cells via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. FASEB J. 21, 2798–2806. (doi:10.1096/fj.06-7717com) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ma L, Jia J, Niu W, Jiang T, Zhai Q, Yang L, Bai F, Wang Q, Xiong L. 2015. Mitochondrial CB1 receptor is involved in ACEA-induced protective effects on neurons and mitochondrial functions. Sci. Rep. 5, 12440 (doi:10.1038/srep12440) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Balenga NA, et al. 2011. GPR55 regulates cannabinoid 2 receptor-mediated responses in human neutrophils. Cell Res. 21, 1452–1469. (doi:10.1038/cr.2011.60) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ma F, Zhang L, Westlund KN. 2009. Reactive oxygen species mediate TNFR1 increase after TRPV1 activation in mouse DRG neurons. Mol. Pain 5, 31 (doi:10.1186/1744-8069-5-31) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chavez AE, Chiu CQ, Castillo PE. 2010. TRPV1 activation by endogenous anandamide triggers postsynaptic long-term depression in dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1511–1518. (doi:10.1038/nn.2684) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Talbot S, Dias JP, Lahjouji K, Bogo MR, Campos MM, Gaudreau P, Couture R. 2012. Activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin induces functional kinin B(1) receptor in rat spinal cord microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 16 (doi:10.1186/1742-2094-9-16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hofmann NA, Barth S, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Klec C, Strunk D, Malli R, Graier WF. 2014. TRPV1 mediates cellular uptake of anandamide and thus promotes endothelial cell proliferation and network-formation. Biol. Open 3, 1164–1172. (doi:10.1242/bio.20149571) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Adam-Vizi V, Starkov AA. 2010. Calcium and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation: how to read the facts. J. Alzheimers Dis. 20(Suppl 2), S413–S426. (doi:10.3233/jad-2010-100465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pandey D, Gratton JP, Rafikov R, Black SM, Fulton DJ. 2011. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates the phosphorylation and activation of NADPH oxidase 5. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 407–415. (doi:10.1124/mol.110.070193) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nishio S, et al. 2012. Activation of CaMKII as a key regulator of reactive oxygen species production in diabetic rat heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 52, 1103–1111. (doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Toyama T, Nakamura H, Harano Y, Yamauchi N, Morita A, Kirishima T, Minami M, Itoh Y, Okanoue T. 2004. PPARalpha ligands activate antioxidant enzymes and suppress hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 697–704. (doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.110) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chung SS, et al. 2009. Glutathione peroxidase 3 mediates the antioxidant effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in human skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 20–30. (doi:10.1128/mcb.00544-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Marsicano G, Moosmann B, Hermann H, Lutz B, Behl C. 2002. Neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids against oxidative stress: role of the cannabinoid receptor CB1. J. Neurochem. 80, 448–456. (doi:10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00716.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang M, Abais JM, Meng N, Zhang Y, Ritter JK, Li PL, Tang WX. 2014. Upregulation of cannabinoid receptor-1 and fibrotic activation of mouse hepatic stellate cells during Schistosoma J. infection: role of NADPH oxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 71, 109–120. (doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wei Y, Wang X, Wang L. 2009. Presence and regulation of cannabinoid receptors in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Mol. Vis. 15, 1243–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]