Abstract

Myzozoans (which include dinoflagellates, chromerids and apicomplexans) display notable divergence from their ciliate sister group, including a reduced mitochondrial genome and divergent metabolic processes. The factors contributing to these divergent processes are still poorly understood and could serve as potential drug targets in disease-causing protists. Here, we report the identification and characterization of a small mitochondrial protein from the rodent-infecting apicomplexan parasite Plasmodium berghei that is essential for development in its mosquito host. Parasites lacking the gene mitochondrial protein ookinete developmental defect (mpodd) showed malformed parasites that were unable to transmit to mosquitoes. Knockout parasites displayed reduced mitochondrial mass without affecting organelle integrity, indicating no role of the protein in mitochondrial biogenesis or morphology maintenance but a likely role in mitochondrial import or metabolism. Using genetic complementation experiments, we identified a previously unrecognized Plasmodium falciparum homologue that can rescue the mpodd(−) phenotype, thereby showing that the gene is functionally conserved. As far as can be detected, mpodd is found in myzozoans, has homologues in the phylum Apicomplexa and appears to have arisen in free-living dinoflagellates. This suggests that the MPODD protein has a conserved mitochondrial role that is important for myzozoans. While previous studies identified a number of essential proteins which are generally highly conserved evolutionarily, our study identifies, for the first time, a non-canonical protein fulfilling a crucial function in the mitochondrion during parasite transmission.

Keywords: alveolates, apicomplexa, Plasmodium, transmission, mitochondrion, ookinete

1. Background

The superphylum Alveolata consists of a large collection of eukaryotic organisms representing diverse living environments, morphologies and trophic strategies [1]. In many cases, these organisms have diverged from typically canonical cellular processes and arrangements in order to survive and reproduce in their corresponding niches. For instance, the mitochondria of apicomplexan parasites and related phototrophic chromerids such as Vitrella and Chromera are characterized by a reduced genome size when compared with ciliates such as Tetrahymena [2]. There is also a notable absence of some classical units of the electron transport chain whereas some enzymes, such as branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase, have been assigned to additional non-classical enzymatic roles (for recent reviews, see [3,4] as well as [5,6]). Thus, these organisms have evolved divergent approaches and factors to accomplish the necessary metabolism required for their biology and could provide unique targets for drug development in the case of disease-causing protists.

Malaria is caused by the obligate intracellular apicomplexan Plasmodium, a unicellular organism with a complex life cycle that requires a mosquito vector and a vertebrate host. To achieve transmission, the parasite possesses a genetic repertoire that enables it to switch between different host environments, for example the 37°C circulatory system of the mammalian host and the reduced temperature of the mosquito midgut. During the course of blood-stage infection, a subset of the parasite population develops into gametocytes—sexually immature forms under cell cycle arrest. Upon ingestion by the mosquito vector, the gametocytes rapidly mature into free gametes and male–female fusion results in zygote formation. Subsequently, zygotes develop into ookinetes: motile cells capable of breaching the peritrophic matrix surrounding the blood meal, traversing the mosquito midgut epithelium and converting into oocysts at the basal lamina. Within these oocysts, sporozoites develop that are transmitted back to the mammalian host. The different parasite forms exhibit strikingly different morphologies and express many stage-specific genes [7–10]. An array of factors contribute to the shape alteration of the zygote into the ookinete, including regulated kinase-dependent signalling [11–20], regulation of gene expression [21,22], localization of pellicular proteins required for ookinete shape [23,24] as well as metabolic activity of the parasite mitochondrion [25–30].

During the transmission from mammal to mosquito, the metabolic requirements for the parasite change and, as a result, there is an observable alteration of mitochondrial morphology and activity: in asexual blood stage mitochondria are acristate, and metabolism is assumed to be predominantly achieved by glycolysis, whereas in mosquito stage the mitochondria are well developed to perform tricarboxylate cycling and oxidative phosphorylation [27,31–34]. Accordingly, some genes required for the TCA cycle, electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation are not required for normal blood-stage development, but are nonetheless essential for the formation of infectious ookinetes and subsequent mosquito infection [25–30]. However, the full array of factors required for proper functioning of the Plasmodium mitochondrion still remains unknown.

Here, we report the discovery of a small mitochondrial transmembrane domain protein PBANKA_1222200 and its subsequent characterization in Plasmodium. The protein was named mitochondrial protein ookinete developmental defect (MPODD) owing to the localization of the protein and the observed phenotype when the gene is deleted: mpodd(−) parasites fail to infect the mosquito vector and display a defect in the developmental transition from zygotes to ookinetes in the rodent-infecting parasite P. berghei. Importantly, we identified the currently unannotated corresponding P. falciparum homologue implying that the role of this protein is also relevant to malaria parasites infecting humans. Using bioinformatics, we have identified homologues in many other apicomplexans as well as in the related chromerid Vitrella brassicaformis and the dinoflagellates Perkinsus marinus, Oxyrrhis marina, Karlodinium veneficum and Alexandrium tamarense, showing that this protein probably has a conserved mitochondrial role in myzozoans that already arose in non-parasitic alveolates.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Bioinformatic analysis

Plasmodium sequences were obtained from PlasmoDB (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo/, version 26) and multiple sequence alignments were done using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Potential signal peptides, secondary structures and transmembrane (TM) domains were predicted using SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/), TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/), TMPred (http://embnet.vital-it.ch/software/TMPRED_form.html), HHPred (http://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/hhpred) and dense alignment surface DAS method [35]. The mitochondrial localization prediction algorithm MitoProt II (v. 1.101) was employed to assess possible export to this organelle [36]. Phylogenetic trees were created using iTOL (http://itol.embl.de/), and the molecular weight of probed proteins was calculated with Expasy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/).

2.2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v. 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Datasets with more than two conditions were tested with a one-way ANOVA. Normally distributed datasets limited to two groups were tested by using Student's t-test, whereas non-parametric sets were tested using a Mann–Whitney test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

2.3. Experimental animals and parasite lines

Female four- to six-week-old NMRI and C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Janvier laboratories. For all transfections and genetic modifications, the P. berghei ANKA strain was used as recipient line [37].

2.4. Generation of parasite lines mpodd(−), mpodd::mCh, mpodd(−);mpoddPBANKA and mpodd(−);mpoddPF3D7

mpodd(−) parasites were generated by amplifying 1132 bp upstream of PBANKA_1222200 via PCR with the primers 1 and 2 (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The PCR product was subcloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and mutated using site-directed mutagenesis (primers 7 and 8; electronic supplementary material, table S1) to remove a single restriction site for NdeI. This was required to clone the 5′ UTR of PBANKA_1222200 directly in front of mCherry to track promoter activity in vivo. The mutated 5′ UTR was cloned via SalI and NdeI sites into the Pb262CSmChef1ahDHFRyFCU vector that contains the mCherry gene and the positive–negative selection marker hdhfr-yfcu [38]. To introduce the second site for homologous recombination, the fragment 632 bp downstream of PBANKA_1222200 was amplified using the primers 5 and 6 (electronic supplementary material, table S1) and cloned into the Pb262-PBANKA1222200KO-int vector via HindIII and XhoI. The final vector Pb262-PBANKA1222200KO was digested (SalI and XhoI) and transfected into P. berghei ANKA parasites [39,40], giving rise to the mpodd(−) line. C-terminally mCherry-tagged parasites were generated in the same way with the exception that a different primer combination (primers 3 and 4; electronic supplementary material, table S1) was used to amplify the 5′UTR together with the open reading frame (ORF) of PBANKA_1222200. The final vector Pb262-PBANKA1222200TAG was transfected into P. berghei ANKA parasites and selected with pyrimethamine to generate the mpodd::mCh line. To complement knockout parasites, the PBANKA_1222200 ORF was amplified with flanking regions upstream and downstream using the primers 1 and 6 (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The PCR product was subcloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector and fully sequenced (GATC-Biotech Ltd, Konstanz) to ensure the sequence was free of mutations. The resulting pGEM-PbComp vector was digested (SalI and XhoI) and transfected into mpodd(−) parasites to generate the mpodd(−);mpoddPBANKA line. We used the gene in/marker out approach based on selection with 5-fluorocytosine (1.5 mg ml−1) to select for parasites that have taken up the desired DNA construct [41]. The ORF of the P. falciparum homologue was synthesized (GeneArt, Invitrogen Ltd) without the intron and cloned via the restriction enzymes NdeI and HindIII in the Pb262-PBANKA1222200KO vector to replace the mCherry gene and the positive–negative selection marker hdhfr-yfcu. In a further step, the 3′ UTR of PBANKA_1222200 was amplified via PCR using the primers 6 and 9 (electronic supplementary material, table S1) and cloned into the Pb262-PF3D7Comp-int vector. The resulting Pb262-PF3D7Comp vector was digested (SalI and XhoI) and transfected into the mpodd(−) line. Selection with 5-fluorocytosine gave rise to mpodd(−);mpoddPF3D7 parasites. All used parasite lines in this study were cloned by limiting dilution to generate isogenic populations. Mice infected with parasites obtained from transfections (parental population) were grown to a parasitaemia of 0.3–1%. Donor mice were sacrificed, and blood was taken by cardiac puncture. Blood-stage parasites were diluted in PBS to 0.8 parasites per 100 µl. A total volume of 100 µl of the last dilution step was injected intravenously into 10 NMRI mice. Blood of infected mice was smeared from day 7 to day 14 [39]. Each mouse that was parasite-positive was assumed to be initially infected with a single parasite. Once parasitemia reached approximately 2%, blood was taken and parasites were either frozen for re-infections or purified to isolate genomic DNA. Genomic DNA was isolated using the Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Ltd). Subsequently, obtained parasites were genotyped via PCR (electronic supplementary material, figure S1 and S2). Blood-stage growth rates were calculated during the course of limiting dilutions. Blood smears of infected mice were performed on day 8 post-injection of a single blood-stage parasite and the calculation for asexual growth rates determined using the general formula

|

thus simplified to (no. of total parasites)1/8 [42].

2.5. Gene model confirmation of Plasmodium berghei and Toxoplasma gondii mpodd—identification of Plasmodium falciparum mpodd

Total RNA from mixed blood-stage P. berghei parasites and P. falciparum as well as T. gondii cultures was isolated with TRIzol reagent and reverse transcribed with Superscript II in the presence of oligo d(T) and random hexamers. cDNA was PCR-amplified with primers 18 and 19 for P. berghei mpodd, primers 24 and 25 for P. falciparum mpodd, and primers 22 and 23 for T. gondii mpodd (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Amplicons were subcloned into pGEM (P. berghei and P. falciparum mpodd) or L432 and sequenced to confirm the identity of the transcribed product.

2.6. Life cycle stage-specific reverse transcriptase-PCR

Total DNA and RNA of parasites at different life cycle stages were isolated using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Scientific). cDNA was prepared from isolated RNA using the Superscript II kit. Primers used for PCR amplification of the mpodd locus using Taq polymerase are given in electronic supplementary material, table S1.

2.7. Western blot

To verify expression of the MPODD::mCherry fusion protein, saponin pellets of schizont cultures from mpodd::mCh and mpodd(−) parasites were lysed in 50 µl RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 1% NP40, 0,5% sodium dexoycholate, 0,1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA). Probes were mixed and denaturated with Laemmli buffer and separated on 4–15% SDS–PAGE gels (Mini Protein TGX Gels, Bio-Rad). Gels were blotted on nitrocellulose membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad) and incubated over night with antibodies directed against mCherry (rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1 : 5000 dilution, ab183628 from AbCam) or HSP70 (mouse monoclonal antibody, 1 : 5000 dilution, obtained through the MR4 as part of the BEI Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH: Mus musculus 65, MRA-662, MF Wiser). Secondary anti-rabbit (Immun-Star (GAR)-HRP, Bio-Rad) and anti-mouse antibodies (NXA931, GE Healthcare) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were applied subsequently for 1 h (1 : 10 000 dilution). Signals were detected using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.8. Ookinete cultures

Mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of frozen stocks and parasites allowed to multiply to a parasitaemia of 1.2–2%. Twenty million parasites were transferred to two naive mice. Three days after transfer, efficient transmission ability was assessed by observation of exflagellation events. One drop of infected mouse blood was placed on a microscope slide for 10 minutes at 20°C. Exflagellation events were counted using a light microscope (Carl Zeiss GmBH, Jena, Germany) with a counting grid. If at least two events per field of view (under 40× magnification) were observed, mice were bled by cardial puncture, blood transferred to T-75 cell culture flasks (NUNC Corp) and mixed with 12 ml complete ookinete medium (RPMI-1640, 25 mM Hepes, 300 mg l−1, l-glutamine, 10 mg l−1 hypoxanthine, 50 000 units l−1 penicillin, 50 mg l−1 streptomycin, 2 g l−1 NaHCO3, 20.48 mg l−1 xanthurenic acid, 20% foetal bovine serum, pH 7.8). Cultures were incubated for 20 h at 19°C. For localization studies, ookinetes were used directly from culture. For morphology observations, cultures were transferred to 15 ml tubes and centrifuged for 8 min at 1500 rpm at room temperature. Supernatants were discarded, and red blood cells lysed by the addition of 10 ml of ice-cold 170 mM NH4Cl. After incubation of 10 min on ice, ookinetes were pelleted by 8 min of centrifugation at 1500 r.p.m. (4°C). Pellets were washed with 10 ml HBSS (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and centrifuged again as above. Supernatants were discarded, and the remaining pellets were resuspended in 1 ml ookinete medium. The suspensions were either smeared and stained with Giemsa solution to test for developed ookinetes or directly imaged using a Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss GmBH, Jena, Germany) fluorescence microscope.

2.9. Electron microscopy

Ookinetes were produced as outlined above and purified from uninfected erythrocytes by gradient purification centrifugation on a 63% Nycodenz (in PBS) cushion. In order to more easily visualize the mitochondrial network, we adapted a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining procedure [43,44]. Cells were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde (0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.2) for approximately 1 h at 4°C. Fixed cells were then washed extensively (twice washed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.2, followed by twice washed with 0.1 M Tris buffer pH 7.5) and resuspended in a solution containing 2 mg DAB and 0.06% (v/v) H2O2 in 0.1 M Tris buffer pH 7.5. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature (in the dark) for approximately 80 min and was then washed once with an equivalent volume of distilled water. Prepared cells were postfixed with 1.5% KMnO4 for 20 min at room temperature, rinsed in water and stained overnight in 0.5% uranyl acetate at 4°C. In preparation for imaging, samples were serially dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in Epon (60°C for 8 h) followed by sectioning. Images were acquired on a JEOL JEM-1400 electron microscope at 80 kV using the TemCam F416 (Tietz Video and Image Processing Systems GmBH, Gautig).

2.10. Mosquito infections and analysis

Two donor mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of frozen stocks. Transmission potential was estimated by observing exflagellation events as described above. When at least one exflagellation event per counting field was observed, mice were anaesthetized and fed to mosquitoes for 30 min. Prior to feeding, mosquitoes were starved overnight to ensure maximal bite rates. Infected mosquitoes were kept at 80% humidity and 21°C in a climate chamber until analysed.

To observe the development of oocysts, midguts of 20–30 mosquitoes were isolated at day 12 post-infection. Midguts were dissected in PBS and either directly mounted on a microscope slide for live cell imaging or stained with 0.1% mercurochrome solution for 30 min followed by washing of the stained midguts with PBS [45]. The number of oocysts within stained midguts was counted manually with 10-fold magnification using an Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope. To investigate the sporozoite stage, salivary glands of infected mosquitos were isolated between day 17 and day 24. Salivary glands were dissected in RPMI (supplemented with 50 000 units l−1 penicillin, 50 mg l−1 streptomycin), crushed to release sporozoites and purified with 17% Accudenz as described previously [46]. Purified sporozoites were resuspended in RPMI further supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin (ROTH Ltd) and transferred into a 96-well plate.

2.11. Protein localization

A mCherry-tagged MPODD construct (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) was used for the assessment of protein localization. For all parasite life stages, approximately 200 nM MitoTracker Green FM (Life Technologies, λex 490 nm, λem 516 nm) was employed in line with the manufacturer's recommendations. For blood-stage parasites, a drop of blood from an infected mouse was added to a microscope slide together with the addition of MitoTracker and 1 µg ml−1 Hoechst 33342 DNA dye. Two hundred microlitres of cultured ookinetes were centrifuged for 10 s at 13 000 r.p.m. (room temperature) and resuspended in 20 µl culture medium containing MitoTracker and Hoechst at the above-mentioned concentrations. Purified salivary gland sporozoites were resuspended in 100 µl RPMI supplemented with 3% BSA and the above-mentioned dyes. Two hundred nanomolar cytochalasin D was also included in the sporozoite medium to minimize motility of activated parasites. For liver stage imaging, approximately 20 000 freshly isolated sporozoites were added to Huh7 cells at approximately 70% confluency for 30 min. The cells were then washed and allowed to culture for 28 h at 37°C, 80% relative humidity and 5% CO2. Cells were then incubated in MitoTracker and Hoechst for 30 min at the above-mentioned concentrations and then replaced with regular culture medium (DMEM, 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine). All images were acquired using a spinning disc confocal microscope (Nikon Ti series) with 100-fold magnification (NA 1.4). In order to assess whether the mitochondria of knockout ookinetes had any residual activity as detected by the dye, ookinete cultures of both the knockout and wild-type strains were produced and stained as described above. Approximately 50 ookinetes from each culture were imaged under the same conditions and durations, and the mitochondrial staining measured using the ImageJ ‘measure’ plugin in FIJI [47].

2.12. Estimation of prepatencies by native transmission and sporozoite injections

To assess any possible defects during transmission from vector to host, re-infection experiments were performed. Infected mosquitos between day 17 and day 24 post-infection were separated into cups to 10 each and starved for 6–8 h. Per experiment, four four- to six-week-old C57Bl/6 mice were anaesthesized using 70 µl of a mixture between ketamine and xylazine (87.5 mg kg−1 ketamine, 12.5 mg kg−1 xylazine). One anaesthetized mouse was put on each cup, and mosquitoes were allowed to bite for 10 min on the ventral and dorsal side. Twenty-four hours after feeding, mosquitos that had taken a blood meal were dissected to determine sporozoite numbers within salivary glands and midguts. Additionally, salivary gland sporozoites were dissected from mosquitos at day 17 to day 24 post-infection. Infected salivary glands were stored in RPMI medium (containing 50 000 units l−1 penicillin, 50 mg l−1 streptomycin) and crushed with a pestle to release the sporozoites. The number of sporozoites was counted (in a Neubauer counting chamber) and subsequently diluted to 10 000 sporozoites per 100 µl. For each experiment, four C57Bl/6 mice were injected intravenously with 10 000 sporozoites. The blood of bitten and injected mice was smeared from day 3 to day 10 after injection or exposure to mosquitoes. Taken smears were stained in Giemsa solution (Merck KGaA) and counted using a light microscope with a counting grid. The time between infection and observation of the first parasite within a blood smear was calculated as prepatency.

3. Results

3.1. Mitochondrial protein ookinete developmental defect (PBANKA_1222200) is a predicted transmembrane protein that is present throughout the Plasmodium life cycle and localizes to the mitochondrion

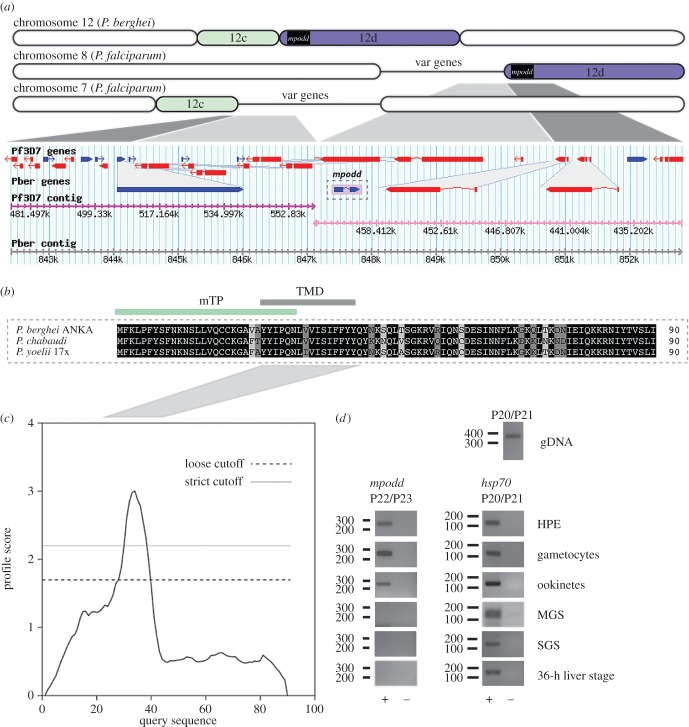

We and others routinely integrate Pb238/262 expression vectors into a presumed silent intergenic P. berghei region. This vector targets a region on chromosome 12 (position 820 043–821 271 bp; PlasmoDB version 26) that represents a synteny break between rodent malaria parasites and the human malaria parasite P. falciparum [48,49] (figure 1a). During the generation of a set of transgenic P. berghei parasites, we noted a marked decrease in transmission efficiency following removal of the resistance marker by negative selection (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). We hypothesized that the bidirectional nature of the ef1α promoter maintains sufficient transcription of a neighbouring, yet at the time unknown gene. Indeed, a recent updated annotation of the P. berghei genome indicated the presence of a previously unrecognized gene (PBANKA_1222200, chromosome 12, position 820 970–821 361 kb) immediately downstream of the integration site. We therefore characterized this gene and experimentally determined its role for life cycle progression. The gene consists of one intron and two exons encoding for a 90-amino-acid protein. Syntenic homologues have been identified in the two related rodent malaria species P. yoelii and P. chabaudi (figure 1b) but are notably absent from P. vivax, P. knowlesi and P. falciparum, and the gene is thus currently annotated as conserved rodent malaria protein with unknown function. The gene is located at a synteny break point between rodent malaria species and human infecting P. falciparum. The P. falciparum locus is characterized by multiple var gene copies: protein encoding genes important for antigenic variation [48]. Owing to the phenotype of the deletion mutants and the localization of the protein (see below), we named the protein MPODD.

Figure 1.

mpodd codes for a transmembrane protein and is located on a synteny break between rodent and human malaria species. (a) Organization of P. berghei chromosome 12 in comparison to chromosomes 7 and 8 from P. falciparum strain 3D7 (not drawn to scale). Evolutionary chromosome rearrangements have resulted in fragmentation of chromosome 12. Therefore, the equivalent segment of P. berghei 12d localizes to chromosome 8 in P. falciparum while segment 12c localizes on chromosome 7. As indicated, mpodd is the first protein coding gene on segment 12d. Sites of crossing-over events are marked by congregations of var genes. Gene locus of mpodd retrieved from PlasmoDB is shown below the scheme: genes are indicated as blue and red arrows, breaks within arrows indicate introns. Corresponding contigs are indicated below the genes. (b) Multiple sequence alignment of MPODD from P. berghei ANKA with its homologues in P. chabaudi, and P. yoelii 17X. Conserved residues are written in white and highlighted in black, highly conserved residues are highlighted in dark grey and mostly conserved residues are highlighted in light grey. Predictions (§2.1) indicate the presence of a transmembrane domain (TMD) and a mitochondrial targeting peptide (mTP) shown as green and black line above the alignment. The alignment was performed with the multiple sequence alignment tool Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). (c) Hydrophobicity plot (dense alignment surface method) based on the sequence of Pb MPODD indicates the presence of a transmembrane domain between tyrosine 25 and tyrosine 40. (d) Total RNA was isolated from indicated life cycle and used in RT-PCR with mpodd-specific primers; (+) and (−) indicate RT+ and RT− cDNA synthesis reactions. Primers specific for hsp70 were used as an expression control for all stages. Amplification of genomic DNA (gDNA) shows the presence of an intron. HPE, non-gametocyte producer line/asexual stage parasites. MGS, midgut sporozoites. SGS, salivary gland sporozoites.

Bioinformatic analysis of MPODD revealed the presence of a TM domain as well as a mitochondrial targeting signal (figure 1b,c). In order to understand the role of MPODD throughout the parasite life cycle, we performed RT-PCR to confirm the gene model and determine its transcription profile. In addition, we tagged the endogenous MPODD C-terminally with mCherry (mpodd::mCh) to assess its localization throughout the parasite life cycle. Expression of the MPODD::mCherry fusion protein was verified by Western blot (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). The mpodd transcript was detected in blood stages and ookinetes (figure 1d), whereas the tagged protein was observed in all life stages with an apparent increased fluorescent signal in mosquito-stage parasites. MPODD::mCh localized to the mitochondrion at all life stages as seen by the distinct co-localization of the fusion protein with the dye MitoTracker (figure 2a).

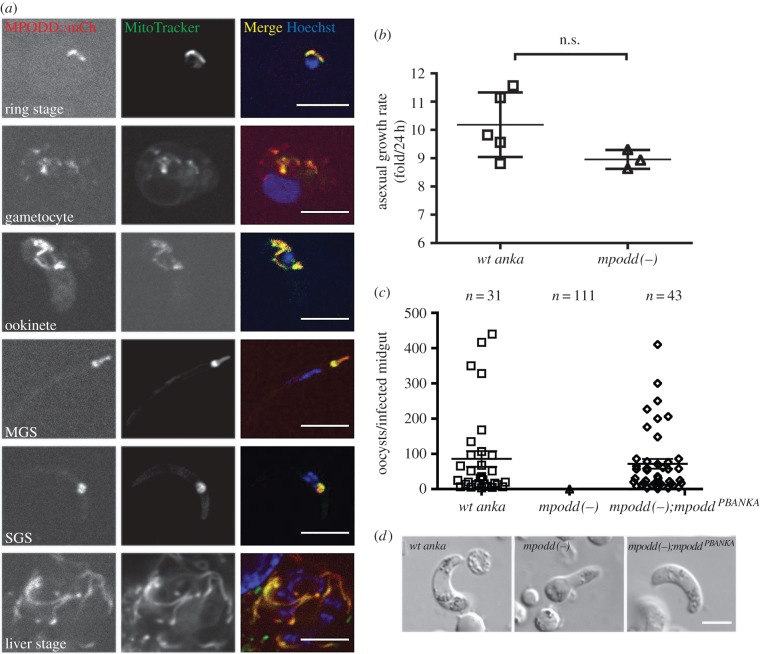

Figure 2.

MPODD is localized to the parasite mitochondrion and is important for zygote to ookinete conversion. (a) C-terminally mCherry tagging of MPODD reveals expression in all life cycle stages and co-localization with MitoTracker Green-FM. MGS, midgut sporozoite. SGS, salivary gland sporozoite. (b) mpodd(−) parasites display comparable blood-stage growth rates. (c) mpodd(−) parasites do not form oocysts in the mosquito midgut, whereas complementation of the knockout with Pb MPODD (mpodd(−);mpoddPBANKA) restores infectivity. Mean with standard error indicated by the horizontal lines. The average wt anka oocyst load per infected midgut was not significantly different from mpodd(−);mpoddPBANKA infected mosquitoes. (d) mpodd(−) parasites do not develop into fully mature ookinetes and arrest at the retort stage. Scale bar: 5 µm.

3.2. mpodd(−) parasites display normal mammalian blood-stage growth, but show a developmental halt in the mosquito

In order to define the potential role for mpodd during life cycle progression, we generated a gene deletion mutant by replacing the entire ORF of mpodd with a pyrimethamine selection cassette following established methodologies (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Gene removal did not affect parasite viability in the blood stages and asexual parasites grew at similar rates to the wild-type control (figure 2b), consistent with reduced mitochondrial functions during asexual development of the parasite in the blood stream. However, mpodd(−) parasites displayed a clear developmental defect when transmitted to the mosquito vector. Even though mpodd(−) parasites showed normal exflagellation of male gametes, independent mosquito feeding experiments did not result in the establishment of oocysts, revealing a complete block in parasite transmission in the gene deletion mutant (figure 2c) that could be due to defects in fertilization or ookinete development. Using standard ookinete in vitro cultures, we could show that knockout parasites failed to develop mature, infectious ookinetes. mpodd(−) mutants typically resembled retort forms with the nucleus still positioned in the bulb-like extension of the zygote (figure 2d), suggesting an important role in final conversion from zygotes to ookinetes. Complementation of the mpodd(−) line with the endogenous P. berghei gene rescued the phenotype completely, reconstituting the ability to produce infectious ookinetes and to produce oocysts in similar numbers per infected midgut to wild-type controls (figure 2c,d; electronic supplementary material, table S2).

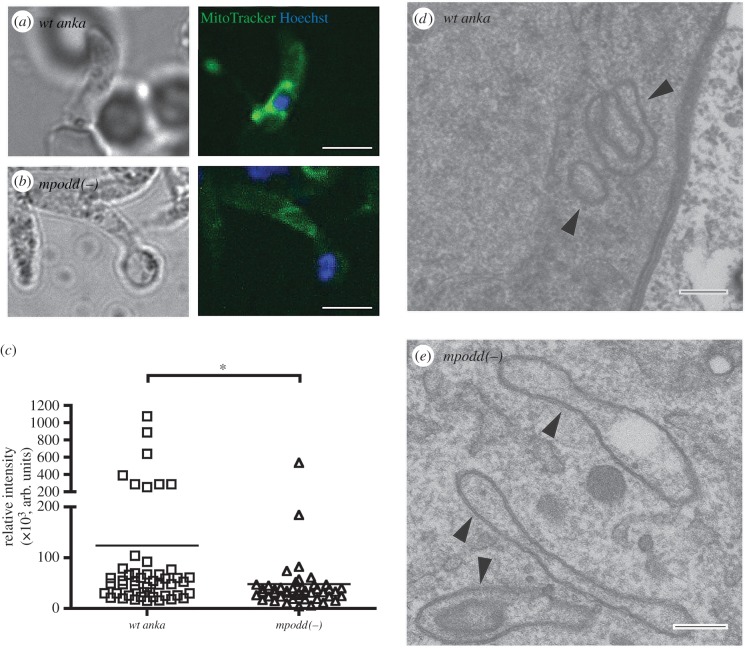

3.3. Absence of MPODD does not affect mitochondrial integrity but results in reduced mitochondrial mass

Given the localization of MPODD to the mitochondrion, we hypothesized that MPODD could play an active role in this parasite organelle (either metabolically or structurally) once in the mosquito. To investigate this, we stained both wild-type and mpodd(−) ookinetes with MitoTracker Green FM dye [50]. This dye fluoresces selectively in the membrane of mitochondria in a membrane potential independent manner and shows the extent of mitochondrial mass in a cell [51,52]. Notably, the signal intensities of mitochondria staining in the knockout line were lower than the wild-type control suggesting reduced mitochondrial mass in the developing ookinete when the gene is absent (figure 3a–c). In order to assess the effect of mpodd deletion on mitochondrial integrity, we isolated ookinetes (or the underdeveloped forms in the case of the knockout), fixed them using standard methodologies and stained for mitochondrial peroxidase activity using DAB staining (see Materials and methods). Electron micrographs show comparable mitochondrial morphology in both the wild-type and knockout lines, suggesting that the absence of MPODD does not affect the overall structural integrity of the organelle as a whole (figure 3d,e).

Figure 3.

mpodd(−) ookinete mitochondria display reduced staining with MitoTracker Green FM dye, suggesting reduced mitochondrial mass. (a,b) Representative images of wild-type and mpodd(−), respectively, stained with Hoechst and MitoTracker Green FM dye, showing diminished MitoTracker signal in mpodd(−) mitochondria compared with wild-type. Scale bar: 5 µm. (c) Quantification of fluorescence intensities of acquired pixels from a set area in the mitochondrial region were measured using the ‘measure’ plugin of FIJI. Individual points on the graph represent the average intensity of a single stained ookinete mitochondrion and the mean represented as a horizontal line. *p < 0.01 (Mann–Whitney test). (d,e) Representative images of glutaraldehyde fixed ookinetes subsequently stained with diaminobenzoic acid revealing comparable structural integrity between parasite lines. Arrowheads indicate stained mitochondrion regions. Scale bar for EM images: 200 nm.

3.4. Identification of a fully functional Plasmodium falciparum homologue and evolutionary origin of MPODD in alveolata

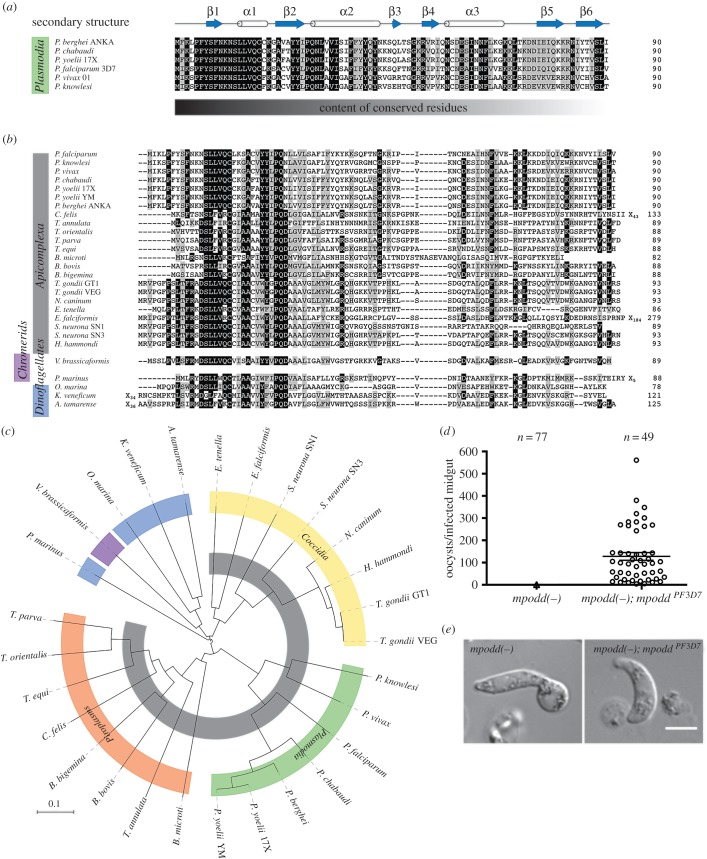

MPODD is currently annotated as a conserved rodent malaria protein with unknown function in P. berghei, P. chabaudi and P. yoelii, and there are no predicted homologues in any of the human malaria parasites. Its key role in the mitochondrion of P. berghei for parasite transmission suggested that this important function might be evolutionarily conserved as the life cycle progression in rodent and human malaria parasites is similar, capable of infecting the same mosquito host. We therefore extended our search for MPODD homologues to other apicomplexan parasites. Using BLASTP, we identified a number of already annotated putative homologues at eupath.db with sequence similarities to Pb MPODD especially within the N-terminal half. Searching EST databases at NCBI with TBLASTN, we identified additional transcripts with coding potential for MPODD homologues in a number of apicomplexan parasites (with the exception of Cryptosporidium which lacks mitochondria and only has mitosomes) as well as phototrophic ancestors in the chromerid and dinoflagellate clades (figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

MPODD arose in a myzozoan ancestor and is functionally conserved. (a) Multiple sequence alignment of MPODD homologues from different Plasmodium species. The secondary structure predicted with HHPred is indicated above the alignment (arrows indicate beta-strands, whereas barrels indicate alpha-helices). Residues that are conserved are written in white and highlighted in black, mostly conserved residues are highlighted in grey. The sequences are especially conserved at the N-terminus, whereas the degree of conserved residues decreases towards the C-terminus (indicated below the alignment). (b) Alignment of all MPODD homologues identified within apicomplexans, chromerids and dinoflagellates. Phyla are indicated on the left. (c) Phylogenetic tree of the sequences aligned in (b). Colours for different subclasses and phyla correspond to (a) and (b), whereas Piroplasmida (orange) and Coccidia (yellow) are also indicated. (d) Oocyst numbers 12 days post-infection of mpodd(−);mpoddPF3D7 in comparison with mpodd(−) infected mosquitoes. Mean with standard error indicated by the horizontal lines. (e) mpodd(−);mpoddPF3D7 and mpodd(−) ookinetes after culturing for 20 h. The mpodd homologue from P. falciparum fully restores normal ookinete development.

Importantly, upon re-visiting the genomic locus in P. falciparum and using TBLASTN, we identified a possible, unannotated P. falciparum homologue on chromosome 8; 425 171–424 797 bp (3D7 strain). The putative P. falciparum homologue Pf MPODD shares 62% identity to P. berghei. In this locus, the P. falciparum homologue is flanked by the same neighbouring genes as PBANKA_1222200 on chromosome 12. Transcription of the gene was supported by a number of ESTs, and we confirmed the conserved exon–intron organization by RT-PCR using cDNA prepared from cultured parasites. In addition, the gene organization of a homologue in Toxoplasma gondii without assigned function (chromosome X, 3690054–3691863 bp, GT1 strain, ToxoDB version 26) was confirmed by RT-PCR suggesting the encoding of the predicted protein (electronic supplementary material, S1).

Within the genus Plasmodium, the sequences adhere to a defined predicted secondary structure (figure 4a). A multiple sequence alignment identified a conserved N-terminal region across all detected myzozoan members with reduced sequence similarity across the C-terminus of the proteins, and a general length of approximately 90 amino acids (figure 4b). With the exception of P. marinus, a phylogentic analysis of MPODD recapitulates the established phylogenetic positions identified in a recent report [53] (figure 4c).

Finally, we introduced the newly identified P. falciparum homologue into the mpodd(−) parasite. Complementation with the proposed P. falciparum homologue from the 3D7 strain (termed Pf mpodd) completely rescued the phenotype of the knockout P. berghei line described above. mpodd(−);mpoddPF3D7 parasites displayed fully formed ookinetes, and the ability to form oocysts in the mosquito vector was equivalent to wild-type and the P. berghei complemented line mpodd(−);mpoddPBANKA (figures 2c and 4d,e; electronic supplementary material, table S2).

4. Discussion

Myzozoans display significant divergence from their ciliate relatives. This is especially obvious in the case of the mitochondrion whereby the myzozoan genomes are markedly reduced with no more than three protein coding genes, the smallest identified [3,54]. Further, key complexes are often absent in these organisms, suggesting modified strategies for effective energy production. Here, we have identified MPODD, a small mitochondrial protein, as a key molecular player in the development of Plasmodium ookinetes and in mosquito-stage establishment. We developed an interest in this gene during the generation of a fluorescent reporter line, where we made use of available vectors that integrate into a region of chromosome 12 previously thought to be transcriptionally silent (position 820 043–821 271 bp) [49]. These transgenic lines behave normally throughout the life cycle [55,56]; however, upon removal of the resistance marker by negative selection [41], we noted a marked decrease in transmission to the mosquito, presumably by affecting mpodd expression. Importantly, while the gene is referred to as an uncharacterized ‘conserved rodent Plasmodium gene’, we have shown here that we can rescue the phenotype by complementation with a homologous gene that we have identified in P. falciparum. This suggests that there could be additional genes currently annotated as rodent malaria specific that are conserved across species, especially given that the numbers of each of this category varies between the annotated genomes (36 genes in P. yoelli, 21 genes in P. chabaudi and 15 genes in P. berghei). Indeed, a bioinformatic analysis of the 15 rodent-specific genes in P. berghei revealed that at least two of these genes (PBANKA_0406600 and PBANKA_1003900) probably have homologues in human infecting Plasmodium species. In addition, through bioinformatics of available sequences, we identified homologues of mpodd in P. vivax and P. knowlesi and transcription of a T. gondii mpodd homologue was confirmed by RT-PCR. A bioinformatic analysis of MPODD within the Alveolata resulted in the identification of numerous homologues in apicomplexans, dinoflagellates and the apicomplexan ancestral organism Vitrella brassicaformis (electronic supplementary material, figure S5) [53]. The phylogenetic distribution of MPODD among myzozoans suggests that the protein fulfils an ancient function within the mitochondrion of this clade. Interestingly, no homologues were identified outside of this clade including its sister group. While we cannot exclude the existence of mpodd-like homologues of lower sequence similarity elsewhere, our current analysis of available databases suggests that mpodd is only present in myzozoans.

MPODD possesses a mitochondrial targeting peptide and a putative TM region (figure 1b,c) suggesting transport into the mitochondria and localization of MPODD to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Interestingly, while the C-terminus is generally divergent in sequence, the N-terminal portion of the protein is well conserved between dinoflagellates, chromerids and apicomplexans. This suggests an important contribution of this region, either in mitochondrial targeting alone or together with its primary function.

MPODD displayed a distinct localization in the mitochondrion throughout the life cycle, indicating a specific function in this organelle. mpodd deletion had no observable effects in the blood stage, which is consistent with other studies assessing important mitochondrial proteins. Parasite mitochondrial activity is only residual in blood-stage parasites, with several knockout lines of mitochondrial enzymes displaying no significant phenotypic defect in blood-stage growth. Phenotypic effects are typically observed in early mosquito stages, largely in ookinete or oocyst formation [25–30]. This suggests a number of important factors are required for transitioning, in both metabolism and morphology, of the parasite mitochondrion during parasite transmission from mammal to arthropod. While these previous studies identified a number of essential proteins that are evolutionarily conserved, our study identifies for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, a non-canonical protein fulfilling a crucial function in the mitochondrion during parasite transmission.

The exact function of MPODD in this organelle is not fully understood. Interestingly, MitoTracker Green FM stains the mitochondria of knockout parasites less intensely than that of wild-type parasites. This suggests that there is significantly reduced mitochondrial mass in parasites lacking this protein. Our electron microscopy studies suggest that the overall integrity of the mitochondrion is comparable to controls. Alteration of organelle mass could be due to an indirect effect of altered metabolism in the cell. Indeed, it has been proposed that human T-effector cells that are more dependent on glycolysis (and less dependent on mitochondrial function) tend to have reduced mitochondrial mass [57]. We could therefore be observing the knockout line displaying less effective stage-specific mitochondrial respiration. Alternatively, reduced MitoTracker Green FM staining when mpodd is absent could indicate decreased protein levels in the mitochondrial membrane [52], and therefore an altered protein import profile, suggesting that MPODD could play a role in transport. MPODD homologues were identified in a wide variety of apicomplexans, chromerids and dinoflagellates, but its apparent absence in the apicomplexan Cryptosporidium is an important observation: this genus possesses a highly reduced mitochondrion and thus is predicted to have only minimal metabolic function [6,58]. mpodd's absence there, together with our results, suggests that MPODD is not involved in the fundamental processes of mitochondrial biogenesis or iron-sulfur cluster formation, which are the remaining ‘mitochondrial’ functions assumed to be intact in Cryptosporidium [58]. We propose that, given the small size of the protein, MPODD possibly acts as an important scaffolding subunit within a larger protein complex that is presumably involved in metabolic function or transport of important metabolic factors (either proteins, lipids or ions) [5,59,60]. Identification of specific interaction partners (for example, using BioID methods) would clarify this mitochondrial role that assists us in understanding the divergent features of an array of organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew Neale for technical assistance; Charlotta Funaya and Stefan Hillmer at the Heidelberg University Electron Microscope Core Facility for their help with EM; as well as Marcel Deponte for helpful discussions and reading the manuscript. We also thank Miriam Reinig for rearing and maintenance of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes and Taco Kooij for the design of the initial transfection plasmids. F.F. is a member of the collaborative research center SFB 1129, D.K. is a member of the Hartmut Hoffman-Berling International Graduate school (HBIGS) and R.D. was a member of CellNetworks (EXC81) at Heidelberg University.

Ethics

All animal experiments were performed according to the FELASA and GV-SOLAS standard guidelines. Animal experiments were approved by the responsible German authorities (Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe).

Data accessibility

Bioinformatic details of all MPODD homologues used in this study, both for sequence comparisons and complementation experiments, can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to study design, interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. D.K., G.R.M. and R.G.D. performed the molecular biology work and analysed the data. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the medical faculty of Heidelberg University, the European Union Framework 7 network of excellence EVIMalaR and by grants from the European Research Council (StG 281719) and the Heidelberg University cluster of Excellence CellNetworks (EcTop4) to Friedrich Frischknecht. We acknowledge the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

References

- 1.Adl SM, et al. 2012. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 59, 429–493. (doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegontov P, et al. 2015. Divergent mitochondrial respiratory chains in phototrophic relatives of apicomplexan parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1115–1131. (doi:10.1093/molbev/msv021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obornik M, Lukes J. 2015. The organellar genomes of Chromera and Vitrella, the phototrophic relatives of apicomplexan parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 129–144. (doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104449) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacot D, Waller RF, Soldati-Favre D, MacPherson DA, MacRae JI. 2016. Apicomplexan energy metabolism: carbon source promiscuity and the quiescence hyperbole. Trends Parasitol. 32, 56–70. (doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.09.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dooren GG, Stimmler LM, McFadden GI. 2006. Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium mitochondrion. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 596–630. (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00027.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danne JC, Gornik SG, Macrae JI, McConville MJ, Waller RF. 2013. Alveolate mitochondrial metabolic evolution: dinoflagellates force reassessment of the role of parasitism as a driver of change in apicomplexans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 123–139. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mss205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan SM, Franke-Fayard B, Mair GR, Lasonder E, Janse CJ, Mann M, Waters AP. 2005. Proteome analysis of separated male and female gametocytes reveals novel sex-specific Plasmodium biology. Cell 121, 675–687. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttery DS, Roques M, Holder AA, Tewari R. 2015. Commit and transmit: molecular players in Plasmodium sexual development and zygote differentiation. Trends Parasitol. 31, 676–685. (doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.08.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matuschewski K, Ross J, Brown SM, Kaiser K, Nussenzweig V, Kappe SH. 2002. Infectivity-associated changes in the transcriptional repertoire of the malaria parasite sporozoite stage. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41 948–41 953. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M207315200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasonder E, et al. 2008. Proteomic profiling of Plasmodium sporozoite maturation identifies new proteins essential for parasite development and infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000195 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000195) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva-Neto MA, Atella GC, Shahabuddin M. 2002. Inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase blocks morphological differentiation of Plasmodium gallinaceum zygotes to ookinetes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14 085–14 091. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M107903200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tewari R, Straschil U, Bateman A, Bohme U, Cherevach I, Gong P, Pain A, Billker O. 2010. The systematic functional analysis of Plasmodium protein kinases identifies essential regulators of mosquito transmission. Cell Host Microbe. 8, 377–387. (doi:10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reininger L, et al. 2005. A NIMA-related protein kinase is essential for completion of the sexual cycle of malaria parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31 957–31 964. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M504523200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reininger L, Tewari R, Fennell C, Holland Z, Goldring D, Ranford-Cartwright L, Billker O, Doerig C. 2009. An essential role for the Plasmodium Nek-2 Nima-related protein kinase in the sexual development of malaria parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20 858–20 868. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.017988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttery DS, et al. 2012. A unique protein phosphatase with kelch-like domains (PPKL) in Plasmodium modulates ookinete differentiation, motility and invasion. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002948 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002948) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guttery DS, et al. 2014. Genome-wide functional analysis of Plasmodium protein phosphatases reveals key regulators of parasite development and differentiation. Cell Host Microbe. 16, 128–140. (doi:10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philip N, Vaikkinen HJ, Tetley L, Waters AP. 2012. A unique Kelch domain phosphatase in Plasmodium regulates ookinete morphology, motility and invasion. PLoS ONE 7, e44617 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttery DS, et al. 2013. The Plasmodium berghei Ca2+/H+ exchanger, PbCAX, is essential for tolerance to environmental Ca2+ during sexual development. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003191 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patzewitz EM, et al. 2013. An ancient protein phosphatase, SHLP1, is critical to microneme development in Plasmodium ookinetes and parasite transmission. Cell Rep. 3, 622–629. (doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akinosoglou KA, Bushell ES, Ukegbu CV, Schlegelmilch T, Cho JS, Redmond S, Sala K, Christophides GK, Vlachou D. 2015. Characterization of Plasmodium developmental transcriptomes in Anopheles gambiae midgut reveals novel regulators of malaria transmission. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 254–268. (doi:10.1111/cmi.12363) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko I, Iwanaga S, Kato T, Kobayashi I, Yuda M. 2015. Genome-wide identification of the target genes of AP2-O, a Plasmodium AP2-family transcription factor. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004905 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerreiro A, et al. 2014. Genome-wide RIP-Chip analysis of translational repressor-bound mRNAs in the Plasmodium gametocyte. Genome Biol. 15, 493 (doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0493-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poulin B, et al. 2013. Unique apicomplexan IMC sub-compartment proteins are early markers for apical polarity in the malaria parasite. Biol. Open. 2, 1160–1170. (doi:10.1242/bio.20136163) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos JM, Kehrer J, Franke-Fayard B, Frischknecht F, Janse CJ, Mair GR. 2015. The Plasmodium palmitoyl-S-acyl-transferase DHHC2 is essential for ookinete morphogenesis and malaria transmission. Sci. Rep. 5, 16034 (doi:10.1038/srep16034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boysen KE, Matuschewski K. 2011. Arrested oocyst maturation in Plasmodium parasites lacking type II NADH:ubiquinone dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32 661–32 671. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.269399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hino A, Hirai M, Tanaka TQ, Watanabe Y, Matsuoka H, Kita K. 2012. Critical roles of the mitochondrial complex II in oocyst formation of rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. J. Biochem. 152, 259–268. (doi:10.1093/jb/mvs058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturm A, Mollard V, Cozijnsen A, Goodman CD, McFadden GI. 2015. Mitochondrial ATP synthase is dispensable in blood-stage Plasmodium berghei rodent malaria but essential in the mosquito phase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10 216–10 223. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1423959112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagaraj VA, Sundaram B, Varadarajan NM, Subramani PA, Kalappa DM, Ghosh SK, Padmanaban G. 2013. Malaria parasite-synthesized heme is essential in the mosquito and liver stages and complements host heme in the blood stages of infection. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003522 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003522) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ke H et al. . 2014. The heme biosynthesis pathway is essential for Plasmodium falciparum development in mosquito stage but not in blood stages. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34 827–34 837. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.615831) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke H et al. . 2015. Genetic investigation of tricarboxylic acid metabolism during the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Cell Rep. 11, 164–174. (doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aikawa M, Huff CG, Sprinz H. 1969. Comparative fine structure study of the gametocytes of avian, reptilian, and mammalian malarial parasites. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 26, 316–331. (doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(69)80010-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howells RE. 1970. Mitochondrial changes during the life cycle of Plasmodium berghei. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 64, 181–187. (doi:10.1080/00034983.1970.11686680) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacRae JI, Dixon MW, Dearnley MK, Chua HH, Chambers JM, Kenny S, Bottova I, Tilley L, McConville MJ. 2013. Mitochondrial metabolism of sexual and asexual blood stages of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Biol. 11, 67 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-11-67) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheiner L, Vaidya AB, McFadden GI. 2013. The metabolic roles of the endosymbiotic organelles of toxoplasma and Plasmodium spp. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 452–458. (doi:10.1016/j.mib.2013.07.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cserzo M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10, 673–676. (doi:10.1093/protein/10.6.673) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claros MG, Vincens P. 1996. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur. J. Biochem. 241, 779–786. (doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vincke LH, Bafort J. 1968. Results of 2 years of observation of the cyclical transmission of Plasmodium berghei. Ann. Soc. Belges. Med. Trop. Parasitol. Mycol. 48, 439–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braks JA, Franke-Fayard B, Kroeze H, Janse CJ, Waters AP. 2006. Development and application of a positive-negative selectable marker system for use in reverse genetics in Plasmodium. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e39 (doi:10.1093/nar/gnj033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janse CJ et al. . 2006. High efficiency transfection of Plasmodium berghei facilitates novel selection procedures. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 145, 60–70. (doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.09.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janse CJ, Ramesar J, Waters AP. 2006. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat. Protoc. 1, 346–356. (doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.53) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin JW, Annoura T, Sajid M, Chevalley-Maurel S, Ramesar J, Klop O, Franke-Fayard BM, Janse CJ, Khan SM. 2011. A novel ‘gene insertion/marker out’ (GIMO) method for transgene expression and gene complementation in rodent malaria parasites. PLoS ONE 6, e29289 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spaccapelo R, et al. 2010. Plasmepsin 4-deficient Plasmodium berghei are virulence attenuated and induce protective immunity against experimental malaria. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 205–217. (doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanker JS. 1979. Osmiophilic reagents in electronmicroscopic histocytochemistry. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 12, 1–85. (doi:10.1016/S0079-6336(79)80002-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von der Malsburg K, et al. 2011. Dual role of mitofilin in mitochondrial membrane organization and protein biogenesis. Dev. Cell. 21, 694–707. (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moll K, Ljungstrom I, Perlmann H, Scherf A, Wahlgren M (eds). 2008. Methods in malaria research, 5th edn Paris, France: BioMalPar/MR4 Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kennedy M, et al. 2012. A rapid and scalable density gradient purification method for Plasmodium sporozoites. Malar. J. 11, 421 (doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-421) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schindelin J, et al. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682. (doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kooij TW, Carlton JM, Bidwell SL, Hall N, Ramesar J, Janse CJ, Waters AP. 2005. A Plasmodium whole-genome synteny map: indels and synteny breakpoints as foci for species-specific genes. PLoS Pathog. 1, e44 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0010044) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deligianni E, et al. 2011. Critical role for a stage-specific actin in male exflagellation of the malaria parasite. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1714–1730. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01652.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Invitrogen Ltd. 2010. The molecular probes handbook: a guide to fluorescent probes and labelling technologies, 11th edn, pp. 503–516. Waltham, MA: Thermo Fisher Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pendergrass W, Wolf N, Poot M. 2004. Efficacy of MitoTracker Green and CMXrosamine to measure changes in mitochondrial membrane potentials in living cells and tissues. Cytometry A 61, 162–169. (doi:10.1002/cyto.a.20033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cottet-Rousselle C, Ronot X, Leverve X, Mayol JF. 2011. Cytometric assessment of mitochondria using fluorescent probes. Cytometry A 79, 405–425. (doi:10.1002/cyto.a.21061) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woo YH, et al. 2015. Chromerid genomes reveal the evolutionary path from photosynthetic algae to obligate intracellular parasites. eLife 4, e06974 (doi:10.7554/eLife.06974) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray MW. 2012. Mitochondrial evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011403 (doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011403) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carey AF, Singer M, Bargieri D, Thiberge S, Frischknecht F, Menard R, Amino R. 2014. Calcium dynamics of Plasmodium berghei sporozoite motility. Cell Microbiol. 16, 768–783. (doi:10.1111/cmi.12289) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singer M, Marshall J, Heiss K, Mair GR, Grimm D, Mueller AK, Frischknecht F. 2015. Zinc finger nuclease-based double-strand breaks attenuate malaria parasites and reveal rare microhomology-mediated end joining. Genome Biol. 16, 249 (doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0811-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Windt GJ, Everts B, Chang CH, Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL. 2012. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity 36, 68–78. (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mogi T, Kita K. 2010. Diversity in mitochondrial metabolic pathways in parasitic protists Plasmodium and Cryptosporidium. Parasitol. Int. 59, 305–312. (doi:10.1016/j.parint.2010.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deponte M, Hoppe HC, Lee MC, Maier AG, Richard D, Rug M, Spielmann T, Przyborski JM. 2012. Wherever I may roam: protein and membrane trafficking in P. falciparum-infected red blood cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 186, 95–116. (doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.09.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaidya AB, Mather MW. 2009. Mitochondrial evolution and functions in malaria parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 249–267. (doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073424) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Bioinformatic details of all MPODD homologues used in this study, both for sequence comparisons and complementation experiments, can be found in the electronic supplementary material.