Abstract

The results of quantum yield (QY) study of tryptophanyl glutamate (Trp-Glu), tryptophanyl lysine (Trp-Lys) and lysinyl tryptophan (Lys-Trp) dipeptides over the pH range, 1.5 – 13, show that the charge state of the N-terminal amine, and not the nominal molecular charge determines the QY. When the terminal amine is protonated, QY is low (10−2) for all three dipeptides. As the terminal amine cation is found proximal to the indole ring in Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys conformers but not in those for Lys-Trp, its effect may lie only in the partitioning of energy between nonradiative processes, not on QY reduction. QY is also low when both the N-terminal amine and indole amine are deprotonated. These two low QY states can be distinguished by fluorescence lifetime measurement. Molecular dynamics simulation shows that the Chi 1 conformers persist for tens of nanoseconds such that 100 – 101 nanosecond lifetimes may be associated with individual Chi 1 conformers. The ground state electron density or isosurface of high QY (0.30) 3-methyindole has a uniform electron density over the indole ring as do the higher QY Trp dipeptide conformers. This validates the association of ground state isosurfaces with QY. Excited state orbitals from calculated high intensity, low energy absorption transitions are typically centered over the indole ring for higher QY dipeptide species and off the ring in lower QY species. Thus excited state orbitals substantiate the earlier finding that the ground state isosurface charge density pattern on the indole ring can be predictive of QY.

Keywords: Tryptophan fluorescence, fluorescence lifetime, quantum yield, excited state, molecular dynamics simulation, quantum mechanics calculations

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The fluorescent indole residue of tryptophan is an intrinsic probe of protein structure, responding to its local environment [1–3]. Several spectral parameters are readily obtainable via steady state and time resolved methods [4–6] but their meaning has long been stymied by the complexities of tryptophan (Trp) photophysics [7–9]. Within a protein, several nonradiative processes compete with fluorescence, and several residues---as well as the peptide bond [10–12]---are potential acceptors of an electron transferred from the indole residue of Trp [13–14]. Intramolecular proton transfer quenching is also possible [15–16]. A 1991 study of several Trp dipeptides [17] showed little variation of quantum yield with the identity or position of the second amino acid, but this study was limited to midrange pH values, and avoided amino acids such as histidine, arginine and cysteine, which interact with the indole ring. Additionally, no molecular dynamics or quantum mechanics calculations, which reveal specifics of intramolecular interaction, were carried out.

Through the application of computational methods [18–27] the contribution of solvent, protein, and the indole residue can be separated out. In our previous molecular dynamics study of the Lys-Trp dipeptide in different charge states [28], optimized molecular dynamics conformations did not show the juxtaposition of the terminal amine cation next to the indole ring. Changes in ground state isosurface charge density on the indole ring, resulting from pH-induced changes in off-ring charge state, were shown to correlate with reduced quantum yield and weighted average lifetime, suggesting a static quenching mechanism as an explanation. In this work, Trp-Lys and Trp-Glu dipeptides are similarly examined. Here, the charge state of the terminal amine is found to govern QY up until the point of indole amine deprotonation. To reinforce our findings, we also consider excited state orbitals from calculated absorption spectra, and highest occupied molecular orbital- lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO-LUMO) orbital overlap. Since fluorescence is a vertical transition and we are focusing on fluorescence rather than radiationless decay processes, topology of the excited state potential energy surface, where the energy tracks with motion of a single molecular group, is not considered here. Indeed, energetic overlap (conical intersection) between excited and charge transfer states along a potential energy surface does not guarantee spatial overlap, i.e., that the charge transfer state will be populated. Others have made extensive and valuable study of indole charge transfer states, and convincingly demonstrated that both electron and proton transfer operate as part of the indole deexcitation process [10–16]. Our work yields insight into the electron distribution responsible for the partition of excitation energy between the light (fluorescence) and dark (radiationless) mechanisms of energy dissipation but does not distinguish between the myriad radiationless mechanisms.

In an earlier paper, we examined the fluorescence lifetimes and Chi 1/Chi 2 dihedral angle preferences of Trp-Glu [29]. We discussed the significance of Chi 1 dihedral angle to conformation, the digital nature of conformational transitions, and noted the juxtaposition of the terminal amine cation to the indole ring in several conformers [29]. In that Trp-Glu paper, we also first noted the unusually high charge density on the beta methylene carbon of the Trp-Glu dipeptide from ring planar charge distribution images. Here, we extend our examination of Trp-Glu dipeptides to include isosurfaces, orbital analysis and experimental QYs. We also examine a dipeptide containing a basic amino acid, the Trp-Lys dipeptide, finding a similar role for the terminal amine cation in controlling quantum yield. In the absence of excited state isosurfaces, molecular orbital calculations for Trp-Lys and Trp-Glu species absorption transition are also carried out. We are especially interested in the HOMO and LUMO for the fluorescent 1La transition because similarities between the isosurfaces of higher quantum yield Lys-Trp species and the HOMO have been observed [28]. We examine the LUMOs from most intense absorption transitions to distinguish between fluorescence, a vertical transition between excited and ground state, and dark state processes, where the excited state electron density can be found off-ring.

2. Experimental

Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys dipeptides were purchased from Research Plus, Inc. (Barnegat, NJ) and used without further purification. Aqueous solutions of dipeptide were adjusted to the required pH by additions of 1mM HCl or 1mM NaOH. Quantum yield standards, L-tryptophan and 2-aminopyridine were purchased from Acros Organics/Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) and Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA), respectively, and used without further purification.

2.1 Absorption measurements

Background corrected absorption measurements were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 650 UV-vis spectrometer (Waltham, MA) with a 2 nm slit width, 1 cm path length cuvette and 1 nm interval.

2.2 Fluorescence emission measurements

Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded on a Fluorolog 3 model FL-1000 (Horiba Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ) fluorimeter with 280 nm excitation, 2 nm slits, 1 nm interval and 0.1 sec integration time. Sample concentrations were all < 0.01 mM to avoid inner filter effects.

2.3 Quantum yield determination

Quantum yield measurement and analysis were carried out using the method of Williams et al. [30]. Details of the method can also be found in Eisenberg and Juszczak [28].

2.4 Time-resolved fluorescence lifetime decay measurements

Fluorescence lifetime measurements (20K counts, 2 nm slits) of the Trp-Lys and Trp-Glu dipeptide species were carried out using a laser diode excitation source with a broad (1.47 ns full-width half maximum, FWHM) instrument response function (Horiba Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ). In addition, the Trp-Lys dipeptide species (pH 1.5 – 11) lifetimes were measured on a Ti:sapphire-pumped, lab-built laser system at the NIH-sponsored Ultrafast Optical Processes Laboratory, (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). Instrument response function width for the Ti:sapphire system is 45 ps FWHM.

Additional details about the Ti-Sapphire system can be found in Eisenberg and Juszczak [28]. Excitation was achieved at 280 nm while emission was monitored at 340 nm on both instruments.

2.5 Fluorescence lifetime decay analysis

The lifetimes for decays collected on the diode instrument were determined by iterative convolution using the vendor-provided Decay Analysis software, DAS6. Details of this method can be found in Eisenberg and Juszczak [29]. The lifetime decay data acquired on the Ti-sapphire-pumped system were analyzed with the fitting program, FluoFit (Picoquant, Photonics North America, West Springfield, MA).

3. Computational Details

3.1 Molecular dynamics simulation

All dipeptide species conformations were simulated via the program, GROMACS 4.5.3 [31]. Roughly 1000 water molecules in a cubic box 1 nm greater than the dipeptide boundary were used with periodic boundary conditions in three dimensions. To be sure that all Chi 1 dihedral space was sampled, a 20–30 ns simulation with 0.5 fs time steps was executed. Other details are given in Eisenberg and Juszczak [29].

3.2 Density functional theory calculations

Ab initio quantum mechanical calculations were carried out via the Gaussian 09 software program [32]. Details of our method are given in Eisenberg and Juszczak [28–29] with the following addition and change. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) excited state calculations were carried out with the B3LYP method and the 6-31++g(df,p) basis set to produce excited state orbitals as well as oscillator strengths for the electronic transitions; oscillator strengths are included in the Supporting information. Range-separated basis sets, such as LC-BLYP and LC-PBE [33–35], correct for errors in delocalization, HOMO-LUMO gaps and fluorescence energies, generated by the B3LYP basis set. Fluorescence energy errors are not of concern here because we do not calculate fluorescence energies. However, the results generated by using the B3LYP basis set and by the long-range corrected CAM-B3LYP basis set were compared (Data not shown). Orbitals and isosurfaces were almost identical. In fact, the lowest energy transition for the standard B3LYP basis set was found to be a closer match to the experimental absorption band than for the long-range corrected basis set. GaussView 5.0 software [36] was used for visualization of the dipeptide species and their isosurfaces. Distance between an isosurface and the nuclei of the indole ring are not directly proportional, but can be estimated with this empirically derived formula [28]: d = y0 + Ae(−i/t), where d is the distance in Å between the nucleus and the isosurface, y0 = 0.370, A = 1.105, t = 0.07228, and i = the isosurface value.

4. Results

4.1 Molecular Dynamics

The conformations revealed by the molecular dynamics simulations are defined by the dihedral angle formed by peptide C---Cα---Cβ ---C3, which are labeled in Figure 1. This dihedral angle is commonly called Chi 1. The dipeptide conformations are determined by three possible Chi 1 dihedral angles, 60°, 180°, and 300°, which have been shown to govern dipeptide conformation for tryptophan dipeptides with glycine, and the dipeptides, Lys-Trp and Trp-Glu under all but the most basic conditions [25, 29]. Dipeptide molecules may remain at one of the preferred Chi 1 angles anywhere from ~1 ns to nearly the entire 30 ns simulation (See Supporting Materials, Figures S1 and S2) while conformational switching between these long-lived Chi 1 conformational states occurs within a few femtoseconds, essentially instantaneously [25, 29]. This means that molecular dynamics simulation (MD) predicts populations of Chi 1 conformers that endure for nanoseconds, which can account for nanosecond fluorescence lifetimes. Such conformational switching is not common for other peptide angles (Data not shown). These conformational characteristics have also been found in simulations for the Trp-Gly, Gly-Trp, Trp-Glu and Lys-Trp dipeptide species, and are peculiar to the Chi1 angle [25, 28–29]. Under extreme base conditions, where the indole amine is deprotonated, calculations indicate that a stable Chi 1= 300° conformation does not exist for either Trp-Glu or Trp-Lys.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of tryptophan with carbon atom numbering used in the text.

4.1.1 Trp-Glu Conformations

The energy-minimized, preferred molecular conformations for Trp-Glu species are shown in Figure 2 along with their isosurface; conformational probabilities are listed adjacent to each. This probability represents the percentage of time spent at the associated Chi 1 angle over the course of the simulation, which is 30 ns.

Fig. 2.

Isosurfaces at the 0.020 level for Trp-Glu dipeptide species in different charge states and for aqueous 3-methylindole. Representative Chi 1 conformations are shown for each of the three dominant Chi 1 angles of 60°, 180° and 300° of Trp-Glu. Probabilities (%) for each conformation are given. The color bar at the top of each isosurface indicates the charge scale.

The Chi 1=300° conformation is most favored by the 1+ to 1− charge states of Trp-Glu. This places a terminal amine cation hydrogen close (2.40 – 2.44 Å) to the indole C3. The Chi 1= 180° conformation is also of significant probability for the 1+ to 1− charge states; here the terminal amine cation hydrogen is also in close proximity to the indole C3 (2.42 – 2.45 Å). The Chi 1= 60° conformation for the Trp-Glu1+ specie shows a relatively high probability of 34%; the C-terminal carboxylate is positioned above the indole ring. In the Chi 1=300° conformation of Trp-Glu 1−, a Glu residue oxygen is 3.25 Å from the indole C2. For the 2− and 3− charge states, where the terminal amine is deprotonated, the Chi 1 = 60° conformation dominates, allowing for the positioning of the negatively charged carboxylates away from the indole ring. The Chi 1=300° conformation of Trp-Glu 3− is not assumed during the 30 ns molecular dynamics simulation due to quantum mechanical calculations, as explained above.

4.1.2 Trp-Lys Conformations

The energy-minimized, preferred molecular conformations for Trp-Lys species are shown in Figure 3. Conformation probabilities based on Chi 1 are listed adjacent to each conformation.

Fig. 3.

Isosurfaces at the 0.020 level for Trp-Lys dipeptide species in different charge states. Representative Chi 1 conformations are shown for each of the three dominant Chi 1 angles of 60°, 180° and 300°. Probabilities (%) for each conformation are given. The color bar at the top of each isosurface indicates the charge scale.

The Trp-Lys 2+ specie favors both the Chi 1 = 60° (63%) and the 300° (35%) conformations, where the Lys residue is extended away from the indole ring. In the Chi 1 = 180° and 300° conformations, the terminal amine cation hydrogen is close to the indole C3 (2.42 and 2.35 Å, resp.). For Trp-Lys 1+, all three Chi 1 conformations occur with significant probability, where the terminal carboxylate is close to the ring (Chi 1= 60°) or the terminal amine cation hydrogen is close to the indole C3 (2.46 Å for Chi 1 = 180° and 2.38 Å for Chi 1=300°). For the Trp-Lys zwitterion, the Chi 1= 60° (56%) and 300° (44%) conformations are both favored. The amide oxygen is 3.31 Å from the indole C3 for the 60° conformation while an N-terminal amine hydrogen is 2.75 Å from the indole C3 in the 300° conformation. For Trp-Lys 1−, the Chi 1=300° conformation is heavily favored (88%). Here, the Lys residue is positioned over the indole ring. For the Trp-Lys 2− specie, the Chi 1= 60° conformation is heavily favored (89%); the terminal carboxylate is positioned over the indole ring. As for Trp-Glu 3−, the Chi 1=300° conformation of Trp-Lys 2− is not assumed during the 30 ns molecular dynamics simulation.

4.2 Charge Density at the Indole Ring: Isosurfaces

Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys dipeptide species’ ground state isosurfaces in different charge states, corresponding to changes in pH, and in the three preferred Chi 1 dihedral angle conformations [37], 60°, 180°, 300°, are included in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The isosurface for aqueous 3-methylindole is also included in Figure 2. All isosurfaces are at the 0.020 isosurface distance, where the isosurface value is a function of distance from the indole ring plane [28]. It is important to note that the color range of the charge scale is the same for all isosurfaces, but the numerical scale is different for each charge state of the dipeptides. The zero charge point shifts from red to blue as negative charge increases on the dipeptides (Figs. 2 and 3). This means that comparison of charge density magnitude between different charged dipeptides cannot be based on color. For example, for the Chi 1=180° conformation of Trp-Glu 1− (Fig. 2), yellow surface represents positive charge density whereas for the Chi 1=180° conformation of Trp-Glu 2−, the yellow surface represents negative charge density. The endpoints of the charge density scale for each isosurface are given on the color scale above each, and the zero charge point is indicated. Generally, it is found that negative charge density becomes more evenly distributed and increases over the indole ring at the 0.02 isosurface as the dipeptide backbone and the non-Trp residue gain negative charge. Once the indole amine is deprotonated, the highest charge density on the indole ring is found at the indole amine.

4.2.1 Trp-Glu Dipeptide Charged Species

The Trp-Glu dipeptides 0.02 isosurfaces ranging in molecular charge from 1+ to 3− are shown in Figure 2. The charged states correspond to the molecular charges at pHs employed in the fluorescence studies: pH 1.5 (1+ charge), the N-terminal amine is protonated; at pH 3.5 (0 charge), the C-terminal carboxylate is additionally deprotonated; at pH 5.5 (1− charge state), the Glu carboxylate is also deprotonated; at pH 10.0 (2− charge state), the terminal amine becomes deprotonated; and at pH 13.0 (3− charge state), the indole amine is also deprotonated.

Regarding charge density distribution, we have already noted that negative charge density on the indole increases at the 0.02 isosurface as negative charge on the dipeptide backbone and non-Trp residue increases. At the same time, the charge distribution across the ring plane shifts as dipeptide negative charge increases (Fig. 2). For the Trp-Glu 1+ and 0 charge species, charge density is skewed towards the phenyl portion of the indole ring (C5 – C7), and is found at the indole nitrogen for all three Chi 1 conformations. With the increase in charge to 1−, charge density is still skewed towards the phenyl ring in the Chi 1= 180° conformer, but is more evenly distributed across the indole ring for the most likely Chi 1 = 300° conformation. Increased charge density at C2 and C3 may be due to that on the adjacent Glu residue carboxylate. In the 2− charge state, charge density distribution is highly conformation-dependent. For the most probable conformation (83%), Chi 1= 60°, charge density is now skewed towards the pyrrole ring with highest density at the indole N and C3. For the less probable Chi 1= 300° conformation, charge is concentrated across the indole ring portion closest to the backbone and Glu residue, at C3 --- C5, and C9, as shown in Figure 2. For the least likely (1.8%) Trp-Glu 2− conformation, charge is roughly evenly distributed across the indole ring (Fig. 2, fourth row). When the indole amine is deprotonated (Trp-Glu 3−, Fig. 2 bottom row), the Chi 1= 300° conformation is not populated. In fact, several different starting geometries were attempted while keeping Chi 1~300°, and the Gaussian 09 program consistently refused to produce any stable geometry. The Chi 1= 60° conformation is instead heavily favored (83%). Unlike all other charge states, the Trp-Glu 3− charge density is concentrated on the indole amine, with lesser charge skewed towards the pyrrole ring for both conformations.

As an exercise in studying charge density changes at Cβ, which were first seen in charge isoplane surfaces for Trp-Glu [29], the indole amine proton was shifted to the pyrrole C3, resulting in a Trp-Glu 2− species (Fig. 2, penultimate row). This 3H-indolenine tautomer has been observed in NMR and x-ray structures [38]. Probability distributions for the conformations are not given. For the Chi 1=60° and 300° conformations, charge density is once again shifted towards the phenyl ring as for the Trp-Glu 1+ and Trp-Glu 0 species.

4.2.2 Trp-Lys Dipeptide Charged Species

The 0.02 isosurfaces for Trp-Lys dipeptides ranging in molecular charge from 2+ to 2− are shown in Figure 3. The charged states correspond to the molecular charges at pHs employed in the fluorescence studies: at pH 1.5 (2+ charge), both the N-terminal amine and Lys residue amine are protonated; at pH 3.5. (1+ charge), the C-terminal carboxylate is additionally deprotonated; at pH 5.5 (0 charge state), the terminal amine is also deprotonated; at pH 11.0 (1− charge state), the Lys residue becomes deprotonated; and at pH 13.0 (2− charge state), the indole amine is also deprotonated.

The 0.02 isosurface charge distribution for all Chi 1 conformations of Trp-Lys 2+ and Trp-Lys 1+ is skewed towards the phenyl ring C4 – C7 with some density at the indole N. Additionally, the terminal amine cation can be found in the vicinity of the indole ring for all conformations of these dipeptide cations except for that of the Trp-Lys 1+ Chi 1= 60°. For the Trp-Lys zwitterion, charge density is spread across both the pyrrole and the phenyl rings yet skewed towards C3 – C5 and C9, for the most probable Chi 1 = 60° and 300° conformations. The positively charged Lys residue also curves back over the indole in these two conformations. Charge density is fairly evenly distributed over the indole ring for all Chi 1 conformations of Trp-Lys 1−; C3, C5 and C9 have higher charge density. The neutral Lys residue overlays the indole ring in the heavily favored Chi 1 = 300° conformation of Trp-Lys 1−. When the indole amine is deprotonated (Trp-Lys 2−), charge density on the indole ring is concentrated at the pyrrole nitrogen, a very different arrangement from all the other Trp-Lys charge states.. Shifting the pyrrole amine hydrogen to the C3 (Trp-Lys 1−, extreme base) results in additional charge density on the phenyl ring.

4.3 Orbital Calculations

Lowest energy/highest intensity absorption transitions were calculated for the most probable Chi 1 conformations for each charged dipeptide species. Oscillator strengths for these significantly contributing transitions are included. Transitions that are too low in calculated intensity to significantly contribute to the molecular absorption are not considered. These states are often charge transfer or Rydberg in character. This neglect does not create a problem because we are not focusing our discussion on charge transfer or trying to distinguish between different dark states. Both diffuse and nondiffuse basis sets were used to calculate orbitals with implicit water but the nondiffuse orbitals were in many cases inconsistent with fluorescence experimental results. In some cases, there was no apparent orbital overlap between excited and ground state, with the excited state orbitals being entirely off the ring (Figs. S3A, B and S4A, B) or even cases where both the HOMO and LUMO were entirely off the ring (Fig. S3C), which is not even a feasible result. Paradoxically, for the very low fluorescing Trp-Glu 3− species, the nondiffuse HOMO and LUMO orbitals are located on the indole ring (Fig. S3D). The advantage to using nondiffuse basis sets is to avoid the orbital density extending into unwarranted areas, but if the lack of diffuse orbitals does not even allow for orbital density where it most probably belongs, it is less likely that the diffuse orbitals contain too many artifacts. The following discussion is based on the diffuse orbitals only.

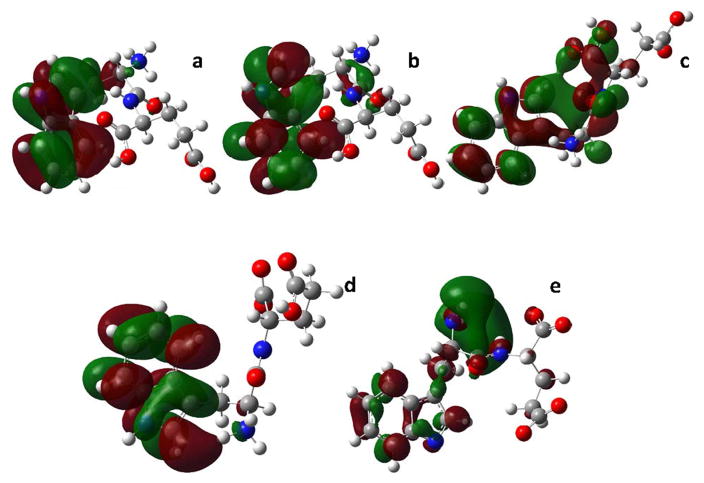

4.3.1 Trp-Glu 1+ transitions

The two most probable conformations of the Trp-Glu 1+ are the Chi 1= 60° (34%) and the Chi 1= 300° (52%) conformations. The former conformation has two lowest energy transitions where both orbitals are centered on the indole ring: HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength, f = 0.0883) and a higher energy HOMO-1 → LUMO (f = 0.049). As shown in Figure 4a, The Trp-Glu 1+ Chi 1= 60° HOMO orbital has electron density concentrated on the indole ring. Continuous density is located on C2-C3, N-C8-C9-C4-C5 and C6-C7. This is a pattern of HOMO orbital density that is common to many of the Trp dipeptides as will be discussed below. Therefore, this particular pattern of HOMO orbital electron density will be referred to as ‘the common HOMO orbital.’ In addition, this HOMO orbital has some electron density on Cα and Cβ.

Fig. 4.

Orbitals for Trp-Glu dipeptide Chi 1 conformations. a. HOMO, Trp-Glu 1+, Chi 1=60° b. LUMO, Trp-Glu 1+, Chi 1= 60° c. LUMO, Trp-Glu 1+, Chi 1=300° d. LUMO, Trp-Glu 0, Chi 1=300° e. LUMO, Trp-Glu 3−, Chi 1=60°.

The orbital electron density for the LUMO for this conformation (Fig. 4b) is also concentrated on the indole ring, but the density is more highly fragmented by nodal planes. It is found individually on C2, C4 and C7 atoms and continuously on N-C8-C9-C3 and C5-C6. Electron density is also found on the peptide bond. The orbitals for the HOMO-1 → LUMO transition are also centered on the indole ring (Data not shown). Other transitions are of too low a calculated intensity to make a significant contribution to the absorbance.

The Trp-Glu 1+, Chi 1= 300° conformation lowest energy transition is the HOMO →LUMO (f = 0.0344) transition. The HOMO orbital electron density is of the common HOMO orbital type (Fig. 4a). The LUMO electron density for this conformation is more fully dispersed over the dipeptide (Fig. 4c). A HOMO → LUMO +1 transition (f = 0.0344) also contributes to the lowest energy transition. The LUMO + 1 is similar in density distribution (Data not shown) to the LUMO (Fig. 4c) but with more density skewed towards the glutamic acid.

4.3.2 Trp-Glu 0 transitions

The Chi 1 = 300° conformation is the most likely (70%) for Trp-Glu 0. The HOMO orbital for this conformation (See Supporting Materials, Figure S5a) is of the common HOMO orbital type (Fig. 4a) except that there is an additional small node between C8 and C9. Orbital density is also seen about the peptide bond. The LUMO for this conformation is shown in Fig. 4d; electron density is concentrated on the indole ring with a small amount of electron density on the terminal amine nitrogen and on the Cα. The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0949.

4.3.3 Trp-Glu 1− transitions

The Chi 1 = 300° is the most probable (65%) for this dipeptide species. The HOMO orbital is of the common HOMO orbital type (Fig. 4a). The orbital electron distribution over the indole ring for the LUMO here is like that shown in Fig. 4d. Additionally, electron density is found over the Cβ and about the peptide bond (Data not shown). The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0856. The HOMO-3 →LUMO transition (f = 0.0459) also contributes significantly to the lowest energy absorbance here. The HOMO-3 orbital electron density is overwhelmingly distributed over the indole ring with continuous density over N-C2, C3-C9-C8-C7 and C4-C5-C6 (Fig. S5b)

4.3.4 Trp-Glu 2− transitions

The Chi 1= 60° conformation is the most likely (83%) for the Trp-Glu 2− species. Its HOMO electron density distribution over the indole ring is like that shown in Fig. S5a. Some density is also found on the Cα and Cβ, and on the amide carbonyl (Data not shown). The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0740. The HOMO-4 orbital also contributes significantly to the dipeptide absorbance. Here, the electron density distribution on the indole is like that shown in Fig. S5b. Some electron density is also found on both backbone termini, and at the peptide bond residues. The density distribution over the indole ring for the associated LUMO is similar to that shown in Fig. 4d. No density is found off the ring. The HOMO-4 → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0740.

4.3.5 Trp-Glu 3− transitions

The most probable conformation (89%) for Trp-Glu 3− is the one with Chi 1= 60°. The HOMO density distribution is similar to that in Fig. S5a. Some density is also found on Cα, Cβ and the peptide carbonyl. Most of the absorption transition is to the LUMO+1, which has an indole ring density distribution like that of Fig. 4d. Very small density appears at Cα, the peptide carbonyl and the N-terminal amine. The HOMO → LUMO+1 oscillator strength is f = 0.0398. However, the LUMO is unique (Fig. 4e). The HOMO→LUMO transition (f = 0.0398) makes a similar contribution to the absorbance. Most of the electron density on the LUMO is distributed about the N-terminus and the peptide bond with small, discrete areas of density on the atoms of the indole ring.

4.3.6 Trp-Lys 2+ transitions

The most populated conformation for Trp-Lys 2+ is the Chi 1=60° (63%). The HOMO orbital density distribution is similar to that shown in Fig. 4a while that for the LUMO is like that shown in Fig. 4b. The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0421. The LUMO+1 orbital also contributes to the absorbance, and it is shown in Fig. 5a. Most of the electron density is over the peptide backbone including the two termini groups and Cβ. Small lobes of density can be found on individual atoms of the indole ring. The HOMO → LUMO+1 oscillator strength is f = 0.0421.

Fig. 5.

Orbitals for Trp-Lys dipeptide Chi 1 conformations. a. LUMO+1, Trp-Lys 2+, Chi 1= 60° b. LUMO+1, Trp-Lys 1+, Chi 1= 300° c. LUMO+2, Trp-Lys 2−, Chi 1=60° d. LUMO, Trp-Lys 2−, Chi 1=60°.

4.3.7 Trp-Lys 1+ transitions

The three possible Chi 1-based conformations are all well-populated, but focus is given to the most likely, Chi 1 = 300° (47%). HOMO and HOMO-1 orbitals participate in the absorption transition, and these are similar to those shown in Fig. S5a and Fig. S5b, respectively. The LUMO orbital is like that shown in Fig. 4b. The HOMO → LUMO and HOMO-1 → LUMO oscillator strengths are both f = 0.0970. The LUMO+1 also contributes to the absorbance, and it is shown in Fig. 5b. Virtually all the electron density is on the peptide backbone with smaller amounts on atoms of the Lys residue. Of all the indole atoms, only the C2 has a small lobe of density. The HOMO → LUMO=1 oscillator strength if f = 0.0312.

4.3.8 Trp-Lys 0 transitions

The Chi 1= 60° conformation is slightly favored (56%) for Trp-Lys 0. The orbital density distribution patterns found here are by now familiar. The HOMO density distribution over the indole is like that in Fig. 4a, the “common HOMO orbital,” with small lobes of density on the backbone. The HOMO-1 orbital also contributes to the absorbance, and indole density distribution is like that seen in Fig. S5b. Some density is also found on the C-terminal carboxylate. The LUMO density distribution is similar to that in Fig. 4b; some density is also located on the N-terminal amine. The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0764 while that for the HOMO-1 → LUMO transition is f = 0.0206. These both constitute the first transition.

4.3.9 Trp-Lys 1− transitions

For Trp-Lys 1−, the Chi 1= 300° conformation dominates (88%). Orbitals for this species have the same shapes as those commonly found for the other species (not including the exceptional Trp-Glu 3−). The HOMO and LUMO densities over the indole ring are like those for Trp-Lys 0, Chi 1=60°, discussed above. Here, the HOMO also has some density over the backbone; the LUMO has very little over the terminal amine nitrogen. The HOMO → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0734. The HOMO-2 also participates in this absorption transition. The density distribution is similar to that in Fig. S5b with no density over the backbone or Lys residue. The HOMO-2 → LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0233.

4.3.10 Trp-Lys 2− transitions

The Chi 1= 60° conformation of Trp-Lys 2− has a probability of 89%. The HOMO → LUMO +1 transition is the dominant contributing transition to indole absorbance; its oscillator strength is f = 0.0336. The HOMO density distribution over the indole ring is like that given in Fig. S5a; there is some density over Cα and Cβ. The LUMO +1 density distribution over the indole is like that of Fig. 4b. The HOMO →LUMO oscillator strength is f = 0.0336. The HOMO → LUMO +2 makes a smaller contributions to the absorbance transition with an oscillator strength of f = 0.0079. The LUMO and LUMO+ 2 orbitals are shown in Figs. 5b and 5c, respectively. The electron density for the LUMO is found almost exclusively over the terminal amine. The electron density for the LUMO+2 orbital is preponderantly over the Lys amine with smaller lobes of density scattered on Lys methyl groups, the backbone and on the indole ring.

4.4 Fluorescence Results

The fluorescence quantum yield results and fluorescence lifetime measurements for the Trp-Glu dipeptide at several pHs are given in Table 1. The corresponding charge states are given above (See Trp-Glu Dipeptide Charged Species).

Table 1.

Quantum Yields and Fluorescence Lifetimes for Trp-Glu Dipeptide at Different pHs.

| pH | Quantum Yield | R2 | Lifetimes (ns) | Amplitude (%) | Average Lifetime (ns) | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 0.036 | 0.99 | 0.095 | 11 | 1.21 | 1.40a | 1.27 |

| 1.28 | 87 | ||||||

| 4.64 | 1.8 | ||||||

| 3.5 | 0.067 | 0.98 | 1.57 | 92 | 1.71 | 2.00 | 1.09 |

| 3.48 | 7.6 | ||||||

| 5.5 | 0.052 | 0.98 | 1.84 | 88 | 2.45 | 2.32 | 1.21 |

| 6.80 | 12 | ||||||

| 10.0 | 0.157 | 0.90 | 1.87 | 35 | 5.68 | 7.16 | 1.22 |

| 7.71 | 65 | ||||||

| 13.0 | 0.071 | 0.96 | 1.97 | 99 | 2.05 | - | 1.24 |

| 8.42 | 1.1 | ||||||

From AS Eisenberg and LJ Juszczak [29]

4.4.1 Trp-Glu

The QY for Trp-Glu at acidic pHs are low, ranging in value from 0.036 – 0.067, as shown in Table 1. At these pHs, the N-terminal amine remains protonated. It is only at pH=10, where the N-terminal amine is deprotonated, that the QY finally increases to 0.157. We note that a QY of 0.34 has been reported for aqueous 3-methylindole [16]. At pH=13, where the indole amine is deprotonated, the QY once again decreases to 0.071.

A parallel set of changes in fluorescence lifetime is found for Trp-Glu over the same pH range. At pH=1.5, a set of three lifetimes is found, which is dominated by a 1.28 ns lifetime; a 4.64 ns lifetime contributes minimally. Increasing the pH to 3.5 results in a dominant 1.57 ns component with a small contribution from a 3.48 ns lifetime. At pH=5.5, the dominant lifetime further increases to 1.84 ns, and the minor component lifetime increases to 6.80 ns. At the alkaline pH of 10.0, the major component lifetime is now the longer one of 7.71 ns, and the shorter lifetime of 1.87 ns has the smaller amplitude. An even longer lifetime of 8.42 ns appears at pH 13, but it has a very small amplitude; a 1.97 ns lifetime dominates. Weighted average lifetimes have been calculated at each pH, and these also appear in Table 1. At acidic pHs, average lifetimes range in value from 1.21–2.45 ns. A lower average lifetime of 1.67 ns at pH 5.5 has been reported [17]. At pH 10, the weighted average lifetime increases to 5.68 ns, but further increase of pH to 13 results in a shorter lifetime of 2.05 ns. Chen et al. [17] report a lifetime of 6.21 ns for Trp-Glu at pH 9.3. A second set of weighted average lifetimes has been computed from lifetimes reported in an earlier publication [29]. The same trend in average lifetime with pH change is found for these lifetimes. For high QY 3-methylindole, a single lifetime of 8.2 ns has been reported [16].

4.4.2 Trp-Lys

The corresponding set of QY measurements and fluorescence lifetimes for Trp-Lys over the pH range 1.5–13 are given in Table 2. At pH 1.5, the QY for the Trp-Lys 2+ species is low, 0.045. QY at pH=5.4 (1+ charge state) is also low: 0.076. At pH=9.3 (0 charge state), where the terminal amine is deprotonated, QY increases to 0.19, and remains high---0.20---at pH=11, where Trp-Lys is in the 1− charge state. At pH=13 (0.1M NaOH), the indole amine is deprotonated, and the QY drops to 0.052.

Table 2.

Quantum Yields and Fluorescence Lifetimes for Trp-Lys Dipeptide at Different pHs.

| pH | Quantum Yield | R2 | Lifetimes (ns) | Amplitude (%) | Average Lifetime (ns) | χ2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 0.045 | 0.97 | 0.480 | 0.301a | 8.9 | 36a | 1.78 | 1.08a | 1.15 | 1.17a |

| 1.44 | 1.52 | 90 | 64 | |||||||

| 3.92 | - | 1.5 | - | |||||||

| 5.4 | 0.076 | 0.99 | 0.494 | 0.677a | 5.7 | 28 | 2.01 | 2.00 | 1.18 | 1.03 |

| 1.67 | 2.51 | 85 | 72 | |||||||

| 5.85 | - | 9.4 | - | |||||||

| 9.3 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 1.80 | 2.10a | 5.9 | 12 | 6.38 | 6.42 | 1.26 | 1.13 |

| 6.67 | 7.01 | 94 | 88 | |||||||

| 11.0 | 0.20 | 0.94 | 1.61 | 1.49a | 6.1 | 22 | 6.35 | 5.17 | 1.19 | 1.10 |

| 5.44 | 6.21 | 48 | 78 | |||||||

| 7.91 | - | 46 | - | |||||||

| 13.0 | 0.052 | 0.95 | 0.0265 | - | 73 | - | 2.37 | - | 1.14 | - |

| 3.45 | - | 12 | - | |||||||

| 12.9 | - | 15 | - | |||||||

Fit to RLBL data, 280 nm excitation, 340 nm emission

Two sets of fluorescence lifetime measurements were obtained for the Try-Lys species. The set of lifetimes in the first column were acquired on the photodiode system (1.47 ns instrument response function, FWHM); lifetime measurements were made for dipeptides spanning the pH range of 1.5 to 13. Lifetimes in the second column were obtained on a Ti-sapphire-laser pumped system (ca. 45 ps instrument response function, FWHM); measurements were made on dipeptides in the 1.5 – 11 pH range.

In general, three lifetimes were obtained for all fluorescence decays measured on the photodiode system except for the decay at pH=9.3. Two lifetimes were obtained for all decays measured with the Ti-sapphire system. For both sets of decays, the dominant lifetime increases (~1.5 →7 ns) as pH increases from 1.5 to 9.3. A second longer, minor lifetime also increases over this pH range for measurements on the diode system: 3.9 →6.7 ns. At pH=11, two lifetimes, 5.4 ns and 7.9 ns, of nearly equal weight are obtained from the photodiode measurement while a 6 ns dominates the Ti-sapphire measurement. A minor component lifetime of 1.6 ns is found at this pH on the photodiode system. A corresponding minor lifetime of 1.5 ns appears in the Ti-sapphire system results. The fluorescence decay results at pH=13 are dominated by a picosecond lifetime of 26 ps with smaller component lifetimes of 3.45 ns and 12.9 ns.

Weighted average lifetimes are also reported in Table 2 for both sets of measurements. Similar nanosecond values are obtained. For pHs 1.5 and 5.4, average lifetimes are 1 – 2 ns. An average lifetime of 1.08 ns at pH 5.5 was obtained by Chen et al. [29]. At pHs 9.3 and 11, lifetimes increase to 5 – 6 ns. In agreement is a published average lifetime of 5.87 ns, pH 9.3 [29]. At pH=13, the single average lifetime drops back to 2 ns.

5. Discussion

In our study of Lys-Trp dipeptide species [28], cationic species exhibit low QY, short (< 1.5 ns) weighted average lifetimes, and ground state indole isosurfaces characterized by low charge density skewed towards the phenyl ring. With increased negative charge, Lys-Trp zwitterionic and 1− charged species were associated with increases in QY and average lifetime, and higher and even distribution of charge density on the indole isosurfaces. Upon deprotonation of the indole amine, QY and weighted average lifetime again decreased while isosurface charge concentrated mainly at the indole amine and on the pyrrole portion of the indole. For Lys-Trp species, the cationic N-terminal amine, which could serve as a charge transfer recipient, was not found in proximity to the indole ring in molecular dynamics studies. Instead, low and skewed charge density on isosurfaces, resulting from the positive charge on the backbone, was associated with low quantum yield and short, weighted average lifetimes.

The effect of backbone positive charge on the skewing of indole pi electron density off the ring was discovered in an earlier study of Trp-Glu [29]. Electrostatic potential surfaces for several Trp-Glu charged species unexpectedly showed negative charge on the indole methylene carbon even when there was little charge on the indole C3. This suggested that the ring pi electron could be attracted off the ring by backbone positive charge. The following discussion reveals similar trends in QY, fluorescence lifetime and distribution of charge density on the indole ring isosurfaces for Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys as pH increases. Comparison of dipeptide isosurfaces with that of high QY (0.34), aqueous 3-methylindole [16] supports the association of an even distribution of charge density over the indole ring with high QY and a ~10 ns. fluorescence lifetime.

5.1 The N-terminal amine charge state controls quantum yield

Similar patterns of association between ring charge distribution (Figs. 2 and 3), QY and highest amplitude or weighted average lifetime (Tables 1 and 2) are found here for Trp-Lys and Trp-Glu species. What also emerges from comparison of the Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys species isosurfaces is that similar distribution of π-electrons on the indole ring is not determined by the nominal molecular charge. What matters is the protonation state of the N-terminal amine. For Trp-Glu, the N-terminal amine is cationic in the molecular 1+ to 1− charge state. For Trp-Lys, the N-terminal amine is cationic in the molecular 2+ and 1+ charge state. As discussed above, charge density at the 0.02 isosurface level is low and skewed towards the phenyl portion of the indole ring for these species. The association of low QY and highest amplitude or weighted average short lifetime with a protonated N-terminal amine is also found for Lys-Trp [28] even though the N-terminal amine cation is not juxtaposed next to the indole ring.

Temperature-dependent (10 – 35°C) study of QY for Trp-Gly and Trp-Ala dipeptides [39–40] at pH 7 (25°C) revealed an increase of 0.01 in QY at the higher temperatures. This QY increase was similarly associated with N-terminal amine cation deprotonation as the pK of deprotonation decreases from 8.2 to 7.3 as temperature increases [41]. We conclude that while the protonation of the terminal amine affects the electron density and its ground state distribution across the ring, resulting in static quenching, the effect of the conformational proximity of this cationic group to the indole may be on the type and distribution of dark state processes. We note that a terminal amine cation hydrogen is within 2.5 Å of the indole C3 for Chi 1= 180° and 300° conformers of Trp-Glu 1+ to 1− and Trp-Lys 2+ to 1+ species.

5.2 Higher quantum yield upon N-terminal amine deprotonation

The QY and highest amplitude or weighted average lifetime increase for the Trp-Glu 2− and Trp-Lys zwitterion and 1− species (Tables 1 and 2) when the N-terminal amine is deprotonated. This is predicted in the calculations as the electron density on the 0.02 isosurface increases, and the density is more evenly distributed over the indole ring (Figs. 2 and 3). Similar trends were found in the earlier study of Lys-Trp [28].

5.3 Effect of deprotonation of the indole amine on ground state isosurfaces

A second route to skewed electron density distribution over the indole ring, and therefore low QY and shortened dominant lifetime, is deprotonation of the indole amine at high pH. Here, overall electron density on the ring is relatively high, as indicated by the shift at the red end of the figure scale to higher negative value (Figs. 2 and 3, bottom), but charge density is shifted to the pyrrole, with high charge density concentrated at the indole amine. A similar association between QY, lifetime and charge density distribution on the ground state isosurface was found for the Lys-Trp dipeptide at high pH [28]. Discussion there within showed that very low QY is associated with hydrogen bonding at the indole amine in several peptides and proteins [28]. Due to the skewed ground state electron density at high pH, the reduced fluorescence is attributed to static quenching. Indeed, the molecular dynamics study indicates almost no interaction between the terminal amine and the indole, and yet there is a severe drop in QY for the both Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys when the indole amine is deprotonated.

5.4 General trends in fluorescence lifetime allow discrimination between low QY species

A general trend of two 100 ns lifetimes, with increasing amplitude for the longer lifetime as pH increases up to the point where the N-terminal amines are deprotonated, is found for both Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys (Tables 1 and 2). Upon indole amine deprotonation, the dominant lifetime is now the shorter 100 ns lifetime (Trp-Glu) or is diminished to 10−1 ns (Trp-Lys). However, we note that the longest lifetime (low amplitude) for both dipeptide species deprotonated at the indole amine is ~10 whereas the longest lifetime for low pH species is closer to 1. A similar trend in lifetime was previously observed for Lys-Trp [28]. Thus fluorescence lifetime analysis distinguishes between the low QY states observed at pH extremes.

For a neutral chromophore in solution, it has been shown that excited state hydrogen bonding between a solvent molecule and a single hydrogen bonding site on the chromophore results in fluorescence emission red shifts and longer average lifetimes. The longer lifetime in alcohols (as opposed to non h-bonding hexane) is a consequence of the hydrogen-bonding solvent-induced decrease in energy of the excited state below that of isoenergetic dark states [42]. For the Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys system discussed here, the effect of excited state hydrogen bonding on average fluorescence lifetime is not straightforward for several reasons. First of all, the solvent is water throughout, although at different pHs. Secondly, the dipeptides are charged at all pHs at more than one site, which provides for multiple hydrogen bonds to water. Additionally, the peptide bond provides two additional hydrogen bonding sites. Here, average fluorescence lifetimes for both Trp-Glu (Table 1) and Trp-Lys (Table 2) follow a trend of starting low and then peaking at a pH range of 9.3–11, followed by a decrease at high pH 13. The fluorescence emission maximum wavelength do not show a similar trend. The emission maximum wavelength for both dipeptides gradually redshift by ~10 nm with increasing pH (Data not shown). Therefore, the complexity of the dipeptide-water interactions does not permit a determination of the effect of excited state hydrogen bonding to solvent on fluorescence lifetime.

5.5 Lifetimes of Chi 1 Conformers and High Amplitude Fluorescence Lifetimes Correlate

MD simulations show that individual Chi 1 conformations can persist under aqueous conditions up to 10s of nanoseconds (Figs. S1 and S2)---the same timescale as measured fluorescence lifetimes (Tables 1 and 2). Dominant Chi 1 conformation probabilities, P, (Figs. 2 and 3) therefore, can be matched to amplitudes, A, of the major fluorescence lifetimes (Tables 1 and 2). Although the absolute difference in conformational probability, P, and amplitude of longest fluorescence lifetime, A, can vary from 0 to 22%, stable Chi 1 conformations of Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys species can account for observed fluorescence lifetime amplitudes.

5.6 Concurrence between LUMO orbitals, isosurfaces and quantum yield

In the absence of excited state isosurfaces, the excited state orbitals that dominate the absorption transitions can be used to discriminate between low and high QY species. Generally, the HOMOs for either the Trp-Glu or Trp-Lys dipeptide species (Figs. 4a and S5a) do not convey the skewed charge density distribution and lower density seen at low pH and extremely high pH on the indole ring ground state isosurfaces (Figs. 2 and 3). This is so because the isosurfaces are a superposition of all contributing orbitals, not just the HOMO, and orbitals do not show the charge density at a specific distance from the ring plane. Therefore individual ground state orbitals are not particularly useful for comparing charge density on closely related species. Indeed, they do not differ much even between species that have disparate QY.

Excited state isosurfaces would be useful for study of the fluorescence emission transition. These calculations are beyond our current level of expertise, and we have relied instead on the calculated excited state orbitals for the highest intensity absorption transitions, which range from LUMO to LUMO+2, for the most probable Chi 1 conformation(s). In the ensuing discussion, the position of charge density on the LUMOs for the most probable conformer of each dipeptide specie is examined in light of the specie’s QY. The HOMOs for all Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys species have the majority of their charge density on the indole ring with smaller lobes of discrete density on the backbone atoms, as discussed above. This HOMO density distribution will be assumed in the following discussion.

LUMO orbitals for all three of the more highly fluorescing dipeptide species, Trp-Glu 2−, Trp-Lys 0 and Trp-Lys 1−, are centered on the indole ring, which is consistent with a fluorescence characterized by a vertical transition. Thus, these diffuse, excited state orbitals are in concurrence with the corresponding even isosurface charge distribution over the indole ring. Furthermore, the significance of the even charge distribution on the indole ring with respect to QY is reinforced by comparison with the isosurface for the high QY 3-methylindole (Fig. 2, last row, rightmost isosurface), where the density is seen to be very evenly distributed across both rings of the molecule.

The LUMO orbitals for the lower fluorescing Trp-Glu 1+ species present a nuanced picture. The LUMO (Fig. 4b) for the Chi 1= 60° conformer is similar to the HOMO (Fig. 4a) where electron density is distributed mostly over the indole ring. Deexcitation of this conformer is expected to contribute mainly to fluorescence. However, the electron density distribution for the LUMO of the Chi 1=300° conformer (Fig. 4c), while still partially remaining over the ring, is dispersed further over the backbone, with some probability on the terminal amine cation and Cβ. Electron density also connects the C-terminal carboxyl oxygen to C2 of the indole ring. This conformer would be expected to contribute more heavily to the nonradiative deexcitation processes.

The electron density for both the HOMO and LUMO (Fig. 4d) of the Trp-Glu 0 Chi 1=300° conformation is predominantly on the indole ring. Some density is found on the terminal amine cation in both orbitals. There is no obvious argument for the lower QY of this Trp-Glu species from examination of the LUMO.

In the case of the Trp-Glu 1− Chi 1=300° conformation, significant electron density is found on the indole ring and on the peptide bond C, O and N of the LUMO. This LUMO also has continuous density between the peptide carbonyl C and the indole C2, which may be used as an argument for nonradiative deexcitation and this species’ lower QY. The excited state for the absorption transition of the low fluorescing Trp-Glu 3−, Chi 1=60° conformation is mainly the LUMO + 1 orbital, where most of the electron density is on the indole ring. Of secondary importance to the absorption transition is the LUMO (Fig. 4e) with a very different electron density distribution: two large volumes of electron density are located near the peptide bond. Excited state relaxation may populate the LUMO, in which case relaxation to the ground state would proceed by a nonradiative mechanism. This explains the low QY of this species.

Conclusions about the excited state orbitals of Trp-Lys species run parallel to those for Trp-Glu. The weakly fluorescing Trp-Lys 2+, Chi 1= 60° conformation and 1+ species, Chi 1= 300° conformation, both have LUMO+1 orbitals that participate in the absorption transition. For these, electron density is predominantly off-ring. LUMOs for both species have continuous electron density extending from the ring to the backbone. The excited state of the absorption transition for the Trp-Lys 2− species is dominated by the LUMO+1 orbital with a smaller contribution from the LUMO (Fig. 5b) and LUMO +2 (Fig. 5c). The electron density of the former is mainly on the indole ring while that for the latter two is off-ring. Again, because the LUMO electron density is off the ring, a nonradiative relaxation mechanism would explain the low QY.

Examination of the LUMO orbitals for these Trp dipeptide conformers presents the possibility of backbone-to-ring deexcitation routes, especially for the lower QY species. The distribution of LUMO electron density suggests that the charge density asymmetry seen in the ground state indole isosurfaces is mirrored by shifts in orbital electron density off the ring in the excited state for these low QY dipeptide species.

6. Conclusions

Two very different flanking residues, one basic and the other acidic, exhibit the same relationship between isosurfaces, quantum yields and fluorescence lifetimes. Both ground state isosurfaces and excited state orbitals present a consistent picture of high and uniform charge density (isosurfaces) or of high electron density (orbitals) over the indole ring when QY of Trp-Lys and Trp-Glu is high (10−1). A longer fluorescence lifetime is also associated with these conditions (~5–8 ns). Reduced and skewed charge density distribution on the indole ground state isosurface is associated with low QY and shorter weighted average fluorescence lifetimes. When the amino terminus is protonated, isosurface charge density is skewed towards the phenyl ring. Also, LUMO and LUMO + 1 excited state orbitals, calculated for the absorption transition of the most likely Chi 1 conformers, either have significant backbone with diminished ring electron density, or electron density is continuous between some segment of the ring and the backbone. When the indole amine is deprotonated, charge density is concentrated at the indole amine and density can be skewed towards the pyrrole ring. The electron density for excited state LUMOs is overwhelmingly off ring for these species.

Thus two structural factors leading to low quantum yield and short average lifetimes have been identified. One is the presence of an N-terminal amine cation. The second structural factor leading to low quantum yield is deprotonation of the indole amine. Here, distinction between the two low QY structural factors can be made on the basis of fluorescence lifetime. Where the indole amine is deprotonated, dipeptides exhibit a low amplitude lifetime of ~10 ns, which is missing from the lifetimes of the low QY dipeptides at low pH. This relationship also holds for Lys-Trp [28].

As shown for Lys-Trp [28], QY may be reduced even where there is no juxtaposition of the terminal amine cation and the indole ring. A ring juxtaposed amine cation may determine the partition of energy between dark state processes including charge transfer.

The isosurface for the higher QY (0.30) 3-methylindole shows the now familiar pattern of uniform charge distribution across the indole ring.

Lastly, the nanosecond persistence found for Chi 1 conformations via MD simulations is consistent with the high amplitude found for individual fluorescence lifetimes of these dipeptides.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Chi 1 dihedral angle changes over time of molecular dynamics simulation for Trp-Lys dipeptide charged species 2+ and 1−.

Figure S2. Chi 1 dihedral angle changes over time of molecular dynamics simulation for Trp-Glu dipeptide charged species 1+ and 3−.

Figure S3. Nondiffuse orbitals for conformations of Trp-Glu species.

Figure S4. Nondiffuse orbitals for conformations of Trp-Lys species.

Figure S5. HOMO orbitals for Trp-Glu species conformations.

Table S1. Calculated oscillator strengths for all Chi1 conformers of all charged species of the Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys dipeptides.

Highlights.

Charge state of the terminal amine in Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys controls quantum yield.

Orbital transitions show charge transfer character for low fluorescing species.

These transitions corroborate ground state isosurface prediction of quantum yield.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH 5SC3GM105562 to L.J.J.). Time-correlated single photon counting measurements were collected at the Ultrafast Optical Processes Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, supported by the National Institutes of Health (9P41GM104605). Computational studies were carried out at the City University of New York High Performance Computing Center, which is supported by NSF grants CNS-0855217, CNS-0958379 and ACI-1126113.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burstein E, Vedenkina N, Ivkova M. Fluorescence and the location of tryptophanresidues in protein molecules. Photochem Photobiol. 1973;18:263–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1973.tb06422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callis PR. Exploring the electrostatic landscape of proteins with tryptophan fluorescence. In: Geddes C, editor. Reviews in Fluorescence 2007. Vol. 4. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 199–248. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reshetnyak Y, Burstein E. Assignments of the components of the fluorescence spectrum of protein to tryptophan residues based on the properties of their microenvironments in a three dimensional structure. Biophysics. 1997;42:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lackowicz J. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Springer Science + Business Media LLC; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valeur B. Molecular fluorescence: principles and applications. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH; Weinheim, Germany: 2001. p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eftink MR. Fluorescence techniques for studying protein structure. Methods Biochem Anal. 1991;35:127–205. doi: 10.1002/9780470110560.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callis PR. Binding phenomena and fluorescence quenching. II: Photophysics of aromatic residues and dependence of fluorescence spectra on protein conformation. J Mol Struc. 2014;1077:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ababou A, Bombarda E. On the involvement of electron transfer reactions in the fluorescence decay kinetics heterogeneity of proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2102–2113. doi: 10.1110/ps.05501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang MC, Petrich JW, McDonald DB, Fleming GR. Nonexponential fluorescence decay of tryptophan, tryptophylglycine, and glycyltryptophan. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:3819–3824. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Liu B, Yu HT, Barkley MD. The peptide bond quenches indole fluorescence. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9271–9278. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Froehlich PM, Nelson K. Fluorescence quenching of indoles by amides. J Phys Chem. 1978;82:2401–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muino PL, Callis PR. Solvent effects on the fluorescence quenching of tryptophan by amides via electron transfer. Experimental and computational studies. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:2572–2577. doi: 10.1021/jp711513b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Barkley MD. Toward understanding tryptophan fluorescence in proteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9976–9982. doi: 10.1021/bi980274n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eftink MR, Jia J, Hu D, Ghiron CA. Fluorescence studies with tryptophan analogs: excited state interactions involving the side chain amino group. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:5713–5723. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shizuka H, Serizawa M, Kobayashi H, Kameta K, Sugiyama H, Matsuura T, Saito I. Excited-state behavior of tryptamine and related indoles. Remarkably efficient intramolecular proton-induced quenching. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1726–1732. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu HT, Colucci WJ, McLaughlin ML, Barkley MD. Fluorescence quenching in indoles by excited-state proton transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:8449–8454. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen RF, Knutson JR, Ziffer H, Porter D. Fluorescence of tryptophan dipeptides: correlations with the rotamer model. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5184–5195. doi: 10.1021/bi00235a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toptygin D, Woolf TB, Brand L. Picosecond protein dynamics: the origin of the time-dependent spectral shift in the fluorescence of the single Trp in the protein GB1. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:11323–11337. doi: 10.1021/jp104425t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callis PR, Petrenko A, Muino PL, Tusell JR. Ab initio prediction of tryptophan fluorescence quenching by protein electric field enabled electron transfer. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10335–10339. doi: 10.1021/jp0744883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callis PR, Vivian JT. Understanding the variable fluorescence quantum yield of tryptophan in proteins using QM-MM simulations. Quenching by charge transfer to the peptide backbone. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;369:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fahlstrom C, Callis PR, Spangler L, Gillispie G. 64th NW Reg. Mtg. Am. Chem. Soc; Tacoma, WA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muino PL, Callis PR. Hybrid simulations of solvation effects on electronic spectra: indoles in water. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:4093–4109. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callis PR, Burgess B. Tryptophan fluorescence shifts in proteins from hybrid simulations: an electrostatic approach. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:9429–9432. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedonder-Lardeux C, Jouvet C, Perun S, Sobolewski AL. External electric field effect on the lowest excited states of indole: ab initio and molecular dynamics study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2003;5:5118–5126. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenberg AS, Juszczak LJ. Correlation of TrpGly and GlyTrp rotamer structure with W7 and W10 UV resonance Raman modes and fluorescence emission shifts. J Amino Acids. 2012;2012:10. doi: 10.1155/2012/735076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon HL, Jarrell HC, Szabo AG, Willis KJ, Somorjai RL. Molecular dynamics simulations of the conformational dynamics of tryptophan. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:1915–1921. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moors SLC, Hellings M, De Maeyer M, Engelborghs Y, Ceulemans A. Tryptophan rotamers as evidenced by x-ray, fluorescence lifetimes, and molecular dynamics modeling. Biophys J. 2006;91:816–823. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenberg AS, Juszczak LJ. The broken ring: reduced aromaticity in Lys-Trp cations and high pH tautomer correlates with lower quantum yield and shorter lifetimes. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:7059–7069. doi: 10.1021/jp503355h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenberg AS, Juszczak LJ. Relating Trp-Glu dipeptide fluorescence to molecular conformation: the role of the discrete Chi 1 and Chi 2 angles. J Comput Chem. 2013;34:1549–1560. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams ATR, Winfield SA, Miller JN. Relative fluorescence quantum yields using a computer controlled luminescence spectrometer. Analyst. 1983;108:1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery J, JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09 Revision A.02. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein T, Eisenberg H, Kronik L, Baer R. Fundamental gaps in finite systems from eigenvalues of a generalized Kohn-Sham method. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:266802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.266802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong BM, Hsieh TH. Optoelectronic and excitonic properties of oligoacenes: substantial improvements from range-separated time-dependent density functional theory. J Chem Theory Comp. 2010;6:3704–3712. doi: 10.1021/ct100529s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong BM, Piacenza M, Sala FD. Absorption and fluorescence properties of oligothiophene biomarkers from long-range-corrected time-dependent density functional theory. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:4498–4508. doi: 10.1039/b901743g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dennington RDI, Keith TA, Millam JM. GaussView 5.0. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babin F, Huynh-Dinh T. Chemical and enzymatic oxidative coupling of 5-hydroxy-N-dimethyltryptamine with amines. J Med Chem. 1987;30:1239–1241. doi: 10.1021/jm00390a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamauchi O, Takani M, Toyoda K, Masuda H. Indole nitrogen-palladium(II) bonding. Chemical and structural characterization of palladium(II) complexes of alkylindoles and intermediacy of the 3H-indole ring. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:1856–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brancaleon L, Crippa PR, Diemmi D. Anomalous temperature fluorescence quenching of N-Trp terminal peptides. Biopolymers. 1995;36:723–733. doi: 10.1002/bip.360360606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brancaleon L, Gasparini G, Manfredi M, Mazzini A. A model for the explanation of the thermally induced increase of the overall fluorescence in tryptophan-X peptides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;348:125–133. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang MC, Petrich JW, McDonald DB, Fleming GR. Nonexponential fluorescence decay of tryptophan, tryptophylglycine, and glycyltryptophan. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:3819–3824. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao GJ, Northrop BH, Han KL, Stang PJ. The effect of intermolecular hydrogen bonding on the fluorescence of a bimetallic platinum complex. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:9007–9013. doi: 10.1021/jp105009t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Chi 1 dihedral angle changes over time of molecular dynamics simulation for Trp-Lys dipeptide charged species 2+ and 1−.

Figure S2. Chi 1 dihedral angle changes over time of molecular dynamics simulation for Trp-Glu dipeptide charged species 1+ and 3−.

Figure S3. Nondiffuse orbitals for conformations of Trp-Glu species.

Figure S4. Nondiffuse orbitals for conformations of Trp-Lys species.

Figure S5. HOMO orbitals for Trp-Glu species conformations.

Table S1. Calculated oscillator strengths for all Chi1 conformers of all charged species of the Trp-Glu and Trp-Lys dipeptides.