Abstract

Context:

The literature regarding work-life balance (WLB) is plentiful, particularly in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I collegiate setting due to its demanding nature as defined by work hours and travel. Despite the comprehensive understanding of factors contributing to WLB for athletic trainers (ATs) in this setting, the effect of time of year has yet to be investigated.

Objective:

To determine the influence sport season timing (ie, preseason, in-season, off-season) can have on perceptions and experiences of WLB for ATs.

Design:

Qualitative, case-study design.

Setting:

Division I collegiate practice setting.

Patients or Other Participants:

Six ATs employed in the Division I college setting (3 women, 3 men) volunteered and completed our study over 1 year. The average age of participants was 31.0 ± 3 years, and they had 9.0 ± 3 years of experience.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We conducted semistructured one-on-one phone interviews with each participant at 4 points during the year (August, November, February, June). All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed inductively, and we used peer review, multiple-analyst triangulation, and member checks for credibility.

Results:

Time of year (eg, competitive in-season), organizational demands (eg, hours and travel), and life stage (eg, roles assumed) were factors that influenced WLB for ATs in the collegiate setting. Having a positive and adaptable mind-set; having coworker, supervisor, and personal support; and engaging in personal or family time were factors that counterbalanced the inhibitors.

Conclusions:

Our results indicate that a career as an AT in the collegiate setting can create WLB concerns; these concerns, however, seem to peak during the competitive in-season for the AT's primary coverage team. Additionally, conflict that arises for ATs seems to be stimulated by time, as work roles are often less accommodating due to the athletic atmosphere.

Key Words: rejuvenation, time management, organizational demands

Key Points

The organizational demands placed upon an athletic trainer in the collegiate practice setting can lead to work-life imbalance, but with support from family, friends, supervisors, and co-workers, work-life balance can occur.

Time of year for the athletic trainer has the potential to negatively or positively affect work-life balance. That is, in-season work schedules are often longer and less flexible than those in the off-season.

An athletic trainer who is positive, adaptable, and accepting of his or her work schedule in the collegiate practice setting can help foster work-life balance.

Work-life balance (WLB) has become a central concern in the United States, as Americans work longer hours and experience more work-family conflict than people in other industrialized countries.1 Moreover, problems with WLB do not discriminate according to economic level; individuals in all job settings are affected, especially those in health professions, including physicians2 and athletic trainers (ATs).3–5 The National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) has placed improving ATs' satisfaction in their personal and professional lives at the forefront of goals for the profession.6 In fact, the NATA will soon release a position statement promoting professional rejuvenation and balance for ATs; this is the first position paper focused on the practitioner.7 The announcement is timely, as WLB has become an increasing concern, particularly because of its effect on retention3,8,9 within the profession. Consequently, examination of the WLB interface has mushroomed over the past few years in athletic training.

Investigators of WLB have examined several practice settings but are often focused on the collegiate practice setting, most notably because of the demands placed upon ATs10,11 in this setting and because it represents the largest employer of ATs.12 Long work hours appear to be the strongest catalyst for causing work-life imbalance as ATs often work more than 40 hours per week to meet their obligations and responsibilities.3,13 Working hours alone are not always the cause of an imbalance, but they appear to play a large role. Recent literature suggests that ATs' departures from the collegiate setting or the profession entirely are directly linked to hours worked,8,14,15 which often restrict time for outside obligations and personal interests. Female ATs have most notably been at the forefront of discussions about departing the profession15; however, recent evidence9 suggests that work-family conflict can stimulate clinical setting or career changes for male ATs as well. In fact, ATs working in the collegiate setting often say that they want more time for their family and feel as though they sacrifice time at home due to work-related responsibilities.16 Despite the challenges many ATs face in attaining WLB, they are able to use time-management skills, prioritize daily responsibilities, develop support systems, and disengage from their AT role in attempts to promote balance.5,14,17 The topic of WLB is multifaceted and often viewed as both negatively and positively influenced by organizational, individual, and sociocultural factors.11,18

The growing body of literature on WLB, however, is saturated with data that examine the occurrence of WLB at a single point in time.3,4,10,11,19 This information has been crucial for understanding the factors that influence WLB and those strategies that help promote it; yet some have suggested anecdotally that time of year could play a role in an AT's assessment of WLB. For example, if interviewed during the off-season, an AT's assessment might not be as negative as if interviewed during preseason training camp. Foundations for these claims center on the hours worked and travel requirements, which appear to be somewhat reduced during off-season.3,13 Still, despite a fairly comprehensive understanding of WLB for ATs in the collegiate setting, researchers have yet to determine how time of year affects WLB. Additionally, these more traditional point-in-time studies offer only a snapshot of current thinking about individual and organizational performance. It is essential to acknowledge variance over time, and the only way to truly assess this variance is to collect data at different time points. By conducting longitudinal research, time can actually be used as an independent variable instead of simply being recognized as a factor.20 Our purpose, then, was to explore how sport season timing (ie, preseason, in-season, off-season) might influence the perceptions and experiences of WLB for athletic trainers. Additionally, WLB should perhaps be viewed not only from an organizational perspective but also by taking into account individual factors such as family values and marital status.21 Our study was guided by the following research questions:

-

1.

How does time of year (ie, preseason, in-season, off-season) affect an AT's assessment of his or her level of WLB?

-

2.

How do marital and family statuses play a role in WLB throughout the year?

METHODS

Research Design

We used a descriptive, single case-study design22 to examine WLB over a 1-year period. The qualitative design allowed us to capitalize on the strengths of one-on-one interviews, including the chance to interact and follow up with our participants. Case-study designs, although not considered a traditional mode of data collection in health sciences, can provide in-depth, quality information regarding WLB. Case-study designs need to be bounded by time or experiences (or both) shared by a group of people22; in this case, our participants were bounded by their evaluation of their experiences of WLB as ATs in the collegiate setting. Mazerolle and Goodman23 established context and structure for this type of study in athletic training.

Participant Sampling

Our sampling, as is standard for case-study designs and other qualitative methods, was purposeful and done via convenience and criterion.22,24 We contacted potential participants directly to determine interest in the study and explain the parameters of data collection. We used convenience sampling via professional relationships as a means to identify and recruit participants based upon the inclusion criteria. Our criteria for inclusion were full-time employment as an AT in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I setting for a minimum of 2 years and approximately 10 years of clinical practice experience. These inclusion criteria would allow them to have attained role continuance (ie, they were established in their roles and had role understanding). Evidence15 also suggests that ATs in the collegiate setting have about 10 years of experience. Furthermore, we wanted to include ATs who represented different marital and family statuses. Recruitment began after institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Connecticut.

Participant Descriptions

Each of the ATs represented different marital and family statuses, including single, married or partnered, and married or partnered with children. Although no differences have been found between sexes or marital or family statuses in athletic training,25 it has been implied that as a person's marital and family status changes, so does the level of WLB.15 In fact, male ATs have recently demonstrated greater struggles in balancing parenthood with their role as an AT.16 Despite these struggles, female ATs reported greater stress levels in trying to manage work and family roles.16 Because of the mixed views on the roles marital and family status can play in WLB, it is important to include ATs who have different roles outside the workplace.

Six ATs agreed to participate and complete all phases of data collection. For case-study research designs, 4 to 6 participants are recommended and considered sufficient.22 Of the 3 women and 3 men, 2 were single, 2 were married, and 2 were married with children (each had 2 children). Participants were 31.2 ± 2.9 years old, with 9.2 ± 2.9 years of experience. The Table provides a full description of each participant. Pseudonyms were assigned after each interview to protect participants' identities.

Table. .

Athletic Trainers' Demographic Information

| Pseudonym |

Age, y |

Years as a Certified Athletic Trainer |

Primary Sport Coverage |

Relationship Status |

Children? |

| Hillary | 31 | 10 | Women's basketball | Single | No |

| Jake | 27 | 5 | Men's and women's track | Single | No |

| Laura | 32 | 10 | Women's soccer | Married | 2 |

| Lindsay | 30 | 8 | Baseball | Married | No |

| Samuel | 31 | 8 | Football | Married | No |

| Scott | 36 | 14 | Men's basketball | Married | 2 |

Procedures

Upon confirmation of consent, we conducted in-depth semistructured interviews with participants. These interviews were completed 4 times during the academic year: August, November, February, and June. We purposefully selected these time points to capture various intensity points in terms of workload and sport season (in-season versus off-season). We chose a semistructured protocol to allow rapport to develop with the participants, as we thought it would enhance the richness of the discussions and create flexibility to explore unanticipated findings while still allowing the interview to be guided by the preestablished questions. During each of the designated time points, we contacted our participants to establish a convenient time to call and complete the interview. Each interview session followed an interview guide that we created to gain an understanding of experiences pertaining to WLB for ATs and how they may change depending upon the time of year. Using previous literature as a guide,3,8 we developed questions that could help us evaluate the effect of time within and outside the sport season. We had 2 peers review the guide for clarity, content, and accuracy. Suggestions and edits were digested, and we made changes accordingly. We also used each interview as a means to allow for other naturally occurring questions to develop and then added those questions to the ensuing interview session. All phone interviews were conducted by the same researcher for consistency and rapport. Each interview session was recorded and then transcribed verbatim upon completion. Field notes were taken during the interviews to aid in transcription, credibility of the findings, and data analysis.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

All demographic data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago IL) to determine descriptive statistics and frequency distributions of the participants. The following steps summarize how we conducted the data analysis: (1) We carefully read all transcripts thoroughly, making notes on initial impressions of the key findings. (2) On our second reading of the transcripts, we looked to identify similarities and then coded the significant pieces of data. (3) We arranged like codes into groups to capture their meaning. (4) All themes presented were included because there was a 50% distribution among participants. Our analyses were ongoing throughout the data-collection process; we kept field notes from our interviews and transcripts from each phase of data collection.

The credibility of the data was secured via 3 methods: peer review, multiple-analyst triangulation, and member checks. Creswell24 recommended using at least 2 methods of data verification to establish trustworthiness and considered peer review the most helpful. Our peer is an experienced researcher with a strong scholarly record that includes editorships, publications, and knowledge of case-study design. We used the peer review to help ensure that our methods met our purpose and that our analyses matched our collected data. Upon completion of transcription and before data analysis, all participants reviewed their transcribed interviews to ensure accuracy and credibility and make any necessary changes. Additionally, after completion of data analysis, we selected 3 participants to review our presentation and representation of its accuracy related to their experiences. Finally, 2 researchers, following the methods described previously, autonomously coded the data before meeting to discuss the emergent themes and theories.

RESULTS

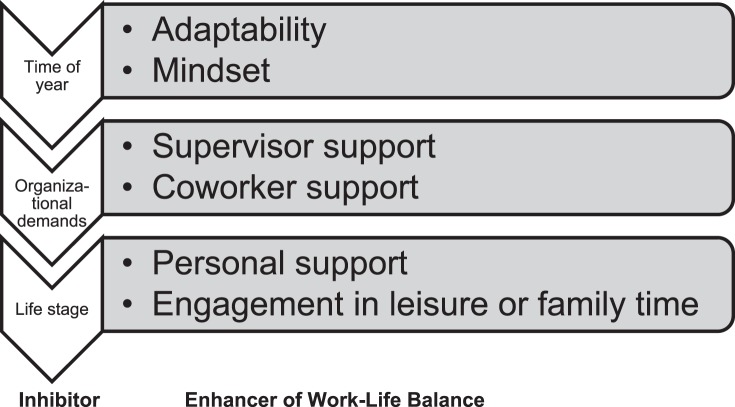

Our general inductive analyses revealed that over the course of a year, there appear to be inhibitors to sustaining WLB in the collegiate setting (Figure). Each of those inhibitors, however, appears to be counterbalanced by several enhancers to WLB (Figure). We discuss these findings in the sections that follow with supporting data from our participant interview sessions.

Figure. .

Barriers and facilitators to work-life balance.

Time of Year

Previous challenges relating to WLB for the AT were described as being facilitated by the time of year.10 That is, work, life, and family responsibilities and obligations can be navigated successfully, but when the AT is providing medical coverage to a team that is in-season, more challenges can arise. Time of year, therefore, reflects the cyclical nature of the professional demands placed on ATs in the collegiate setting. The concept of the time of year can best be summarized by Samuel's comments regarding his role in collegiate athletics as an AT. He shared the following:

There are always demands, and they are constantly changing. Our professional environment, and football specifically, whether it is the season, recruiting, spring ball, summer conditioning, there is always something different going on. You will need to be able to accommodate for that so there [are] ebbs and flows [with demands]. So when there is less demand and stress … I then take more personal time, and then when work is in higher demand, I am at work and we are expected to give more here at work.

Laura, a mother whose primary sport coverage is women's soccer, described how the time of year can influence her WLB. Her reflections are much like Samuel's:

During the off season, I work a little bit less [in hours]. It is definitely different [than being in-season], because of the timing of practice. So usually in the fall we will practice 1 to 3 in the afternoon, which means I will do treatments all day and then have practice and postpractice treatments. So depending upon how long that takes, it can be 5:30–6:00 until I am done and can go home. Where now, because practice is early, I just come to work for 7:30–8:00 and then we practice, which is done by 12:00, and then I can do postpractice treatments and leave by 4:00 each day.

In addition to practice demands, Laura thought the overall schedule in terms of practice times, games, and travel was much less intense in the off-season than during the in-season, which positively influenced her WLB. She continued her interview: “We only have 6 games during the off-season, and they are always a car distance, so we do not have to fly away for weekends. No overnight trips, so that makes a big difference.”

Samuel, like Laura, also described the effect time of year can have on his ability to sustain WLB, primarily related to his workday. During his interviews in August and November, he described his level of WLB as “Not great. As this is the most pressured time of year as far as work demands, I do not have a lot of control over my schedule at this moment.” Samuel's comments were more positive when he was interviewed in June: “I think at this point I am doing a good job with it [balance]. You know over the summer and off-season, there [are] variable amounts of things going on, but the stress is less.”

Jake's comments illustrate the variability of WLB in the collegiate setting due to time of year, as he explained during his February interview: “My work-life balance is probably more work than personal right now as we are [in] the midst of our season. My weekends and nights are a little more work filled than before.” When interviewed in November, before the heart of his season, Jake stated that “my life is the most balanced it has been in a long time.”

Sustaining a Healthy Lifestyle

Time of year also influenced participants' WLB through their ability to sustain a healthy lifestyle. Concerns regarding an AT's ability to engage in and maintain a regular exercise regimen have been noted previously,26,27 and our participants shared their difficulties in doing so, especially when they were in-season, had little autonomy over work schedules, and were working long hours. When asked about her workout routine, Laura was candid: “I usually by now begin working out again. During the in-season, I periodically work out, and then by the end of the season I am not. But now, I am going back to daily or regular workouts.” Laura was also honest about her eating habits, which can be dictated by the day and time of year, and about her struggles to maintain a healthy lifestyle. She reflected that she did a better job of “eating well” and “exercising” when she had more control over her schedule, something that happens during her off-season. In her February interview, Laura shared: “there are days that I can bring lunch but won't eat it until 3:00 in the afternoon, because the day has just taken over. Whereas other days there is more downtime, so I can eat at a more normal time.”

Hillary, like Laura, was also very aware of when her wellness was negatively affected by the time of year. During her in-season interview (February), she said, “I am unsatisfied with my level of wellness and physical activity. My schedule, absolutely [is the cause]; it is hard to find the time to even just be active.” At some point during the year, all 6 participants described struggles with maintaining wellness and physical activity because of time constraints and work demands.

Mind-Set That Showcases Acceptance and Adaptability

This theme speaks to the attitude needed to work in the collegiate setting, namely, that work schedules change and an AT must be flexible. Our participants were acutely aware of the limitations that arise in-season versus off-season or summer months. Those discussions, presented earlier, illustrate potential challenges; however, our participants also used a positive mind-set and demonstrated adaptability to offset these challenges.

Samuel noted the importance of mind-set and the personal reality of job constraints. He said an AT must realize “that you have to have realistic expectations and value the time that you have for work and life. If you do not value the time, you are always going to be dissatisfied about something.” Regarding the variability of the time of year and the limitations it can have for WLB, he stated: “You take what you can get but know, appreciate, and enjoy what you can and do what you have to do work-wise during those specific hour constraints.”

Scott and Laura also commented on how mind-set can help them cope with the demands placed upon them throughout the year but mostly during the in-season of their sport. Scott described:

I look forward to something every weekend. Something fun, that I have planned—like taking my kids to Chuck E Cheese. So that is how I look at my schedule and I say, okay, this is the day I am going to do this and that.

Laura, while reflecting on the year, shared this:

It is all based on knowing what time of year it is. So I know … August to at least the end of October is going to be crazy and just make do and make do with the time you do have. Then I will get a break for a month or so, and then be back at it. Then for a few months I will start up again until the end of May. Then it is easier until August rolls around again. So I kind of just have to get through the hard points, knowing that more time will come to me.

Each participant discussed having a mind-set that was accepting and adaptable. They know that certain times of the year create more challenges due to schedules and travel.

Organizational Demands

Work demands, work schedules, flexibility, travel, and the importance of face time3,11,28 have all been cited as primary factors inhibiting WLB for ATs in the collegiate setting. This theme therefore speaks to those aspects of the workplace that can inhibit WLB for ATs. Our 6 ATs all described the facets just cited as contributors to their reduction in WLB. Hillary shared, “I am averaging 10- to 14-hour days, right now.” She continued, “One of the biggest contributors to the lack of a balanced lifestyle, I feel, is the constant changes to the schedule. My daily schedule changes on a minute's notice.”

Our participants all described working 10- to 12-hour days during their in-season, often reporting to work as early as 5:30 am and leaving between 6:30 and 8:30 pm. In addition, they had very little control over their time in the workplace during the in-season, as illustrated by Samuel's statements related to his current life situation. He said, “I don't have a lot of control over my schedule at the moment. During the long days, you don't have a lot of time, to yourself.” Travel also played an important role in the level of WLB for participants. Jake observed, “I really haven't had the chance to do much of anything else except work. Over the last 4 weeks, we have had trips that were 3 to 4 days long. So it doesn't leave much time for the life portion.”

Support Networks in the Workplace

To combat the demands placed upon ATs, many foster professional relationships with their coworkers and cite supervisor support and understanding as facilitators to improved WLB.10,11 Our participants believed this to be true as well, referencing throughout the interview sessions that coworkers and supervisors were instrumental in creating WLB throughout the year. In fact, our data speak to the concept of cultural work-life support, in which coworkers and supervisors, working together, are able support both professional and family roles through encouragement and job sharing. Lindsay highlighted this when explaining her current work environment:

Our staff, even though we are small, work well together, to really help each other out so that we can all have that time to spend with our families. One of my coworkers said at the beginning of this year, “My son is starting to play high school football.” [The coworker] wanted to leave every Wednesday but asked if we were okay with covering the last 30 minutes of practice. And so we said, “Sure we can do that.” We rarely say no to one another. We definitely want to help each other out. We do really work together, and we are a close-knit staff as we want to help each other out; we want everyone to spend time with their families.

All 6 participants described supportive relationships with their coworkers that fostered valuing family and nonwork roles and helping one another create more time for those roles when necessary. For example, Jake and Scott both described work situations that allowed them to accomplish important tasks in their personal lives, such as attending weddings or social gatherings and picking children up from day care. Scott recounted his perceptions of his current workplace environment and how his staff interacts and demonstrates support:

I think our staff does a really good job of making sure that we help out. And being that I am in the forefront of it now (as a supervisor), we make a point as a staff to say, “OK, you are coming in early, and you are coming in late.” When someone has a late game or practice (11:00), and our facility opens at 6:00 am, we say, “Why don't you leave early that day and go to Costco or whatever you need.” And then they can use that day.

Supervisor Support

Scott, in his role as head AT, illustrated the importance of coworker support as well as the need for the supervisor to endorse collegiality and an understanding of employees' family values and needs. Although he has only been in his role for a short time (<1 year), Scott was able to provide supervisor support, which has recently emerged in the literature as a means to promote balance for ATs in the collegiate athletics setting.29,30

Hillary discussed the role of her supervisor in helping her find balance, especially when the season starts to become overwhelming and it is difficult to find time to balance nonwork roles. She said:

My supervisor is supportive and understands the hectic schedule. He is working with men's basketball, so yesterday when I asked him about getting out early, he was absolutely like “go.” Having his support instead of having a supervisor say, “I am here, so you should be here too,” is crucial. It allows you to not feel guilty about being away from work, even when you should have to feel it. Having a supervisor that is supportive of you is great. When you can actually walk away and leave for half a day and not feel bad about it, so you can actually relax, and get things done. Simple things, like go get dog food, go to the grocery store, all of those things you might not have time for, it makes it a lot easier.

Jake, like Hillary, recognized the importance of having a supervisor who helps him create balance in his life. His first response was that “she plays a major role [in my WLB].” When asked to expand, Jake shared, “She told me: ‘Make sure you make room and time for your personal time and personal life. If not, you will get burnt out or you will reach saturation and will lose a little bit of drive during the track season.'”

Laura spoke about the continued support she received from her supervisor, which included a transition from being married to being married with children. She talked about her experiences:

My boss knows the importance of families, and when I was pregnant he was very supportive of the times when I needed to go to a doctor's appointment; or when I was sick and was in the hospital, he was able to get my coworkers to cover for me. He was very supportive. That is a huge benefit in itself. When you have a boss who understands; it makes it much easier.

Life Stage and Demographics

The life stage and demographics theme speaks to the variables of sex, marital status, and family status and their relationship to WLB. The literature is mixed on whether variables such as sex, marital status, and family status affect the challenges associated with finding WLB.3,14,16 A cursory look at these variables reveals that they have little effect on conflict, but all ATs are susceptible to experiences of WLB. Our participants, regardless of marital or family status, struggled to find balance, and their life stage provided the context for these challenges. For example, the 2 single ATs described problems with creating a balance between work and their personal lives, especially when their team travel demands were high. Simply stated, they struggled with having to manage both domestic and household chores as well as work-related responsibilities. When asked to describe her current level of WLB, Hillary commented, “[My WLB] is probably a zero. As it is all work, there is no life balance at the moment.”

Marriage and Family Status

The 2 single ATs, unlike the ATs who were married or married with children, were solely responsible for household and domestic responsibilities. That is, they were responsible for laundry, grocery shopping, and other tasks that could not be shared with a spouse or partner. Therefore, the conflicts they struggled with were directly related to finding the time to complete necessary household chores outside the workplace. When given the time, however, they did not have to worry about the needs of others, such as a spouse or child, and could then focus on themselves. As Hillary noted: “I try, when I can, to do a couple of things each day just for myself that doesn't have anything to do with athletics or my athletes.”

In contrast, the married and married-with-children ATs needed to balance their personal time among others, such as a spouse and children. The 2 married ATs shared conflicts in creating time for their spouses and balancing each other's work schedules and other demands. Lindsay said:

My WLB is a little less than it has been previously. Our season, in a good way, was extended a few extra weeks, but it took away from that personal time that I do get. So that, combined with my husband doing a lot more work for his job and traveling a lot more, he also was not home for a couple of consecutive weeks. So it has just been a bit tougher to really balance and have some time to ourselves.

Samuel echoed the desire of the married participants to find time for their spouse and to separate his work and personal roles:

I made a commitment to my wife to be around and be present, and so certainly it's making sure that…I'm efficient with the time that I have to be at work and trying to not take my work home with me. And trying to, you know, take advantage of time away when I can.

Although Lindsay mentioned the difficulty of balancing time between her husband and her job during certain times in the year, she acknowledged that the absence of children allowed her to focus on the time she does have to spend with her husband. She explained:

The fact that we don't have children yet definitely plays a role that, you know, I feel like ... when I have home time, I can dedicate it to my husband and myself and it's not being split up too many different ways at this point yet. That's probably ... really the other thing that really plays a part to make me feel at this point that I'm still balanced.

The married-with-children ATs shared how they balance time for work, their spouses, and their children. When asked how he finds balance, Scott responded:

I try to make sure that if I'm going to go into the office early, and to me early is like 5:00 am or 6:00 am in the morning, I try to see to it that I can get out early enough to pick up … our sons … from day care, or I try to see if I'm going in later that I make sure that I'm able to take them to school in the morning and all of that. So that's pretty much every day before work or after work.

Scott also illustrated how being a father and a husband sometimes limited his personal time, mostly because his priorities shifted toward both those roles and are more important than his own needs at times. In terms of his current WLB, Scott commented:

Oh, very bad. I just think it's bad because you'll go on the road or you'll eat late and you won't find time to say, “Hey, let me take an hour out and do what I need to do exercise-wise.” But I bet if someone told me, “Hey, it's gonna affect your well-being if you don't do this,” starting tomorrow I'll make time and I'll block it out in my calendar. But the fact that I don't block it out, and the fact that I don't think it's a priority because my priorities are, hey, let me come in, get my work done. OK, let me get my treatments in, now I gotta get home and get to my kids and family. I think those become priorities and we forget about ourselves.

Marital or family status may not necessarily be a direct contributor to conflict for an AT, but the role assumed can be a catalyst for conflict. The single ATs may not have dependents or a spouse requiring their time and energy, but they do have other aspects of life and family that compete for their time. Unlike the single ATs, however, married and married-with-children ATs must balance their time and resources between themselves and others (ie, spouse and children). Although the situations do not involve the same conflicts, they share outside catalysts, besides individual and work concerns, to WLB.

Personal Support and Personal Time

Having support outside the workplace and creating time away from the workplace were facilitators to WLB. To combat the daily challenges they face in finding a balance between demanding work schedules and personal obligations and responsibilities, the participants relied on personal support networks and engagement in personal or family time.

Both ATs who were married with children described having very supportive and engaging spouses who were able to take on more of the domestic and household duties when necessary to help the AT focus on work and, when at home, to engage with less stress in their family. Laura said, “Lucky for me my husband is so supporting.” Scott highlighted this same point in his discussion of his wife's role in his WLB:

My spouse is very, very, very good at understanding when something changes or if she has to pick up our son[s] instead of me, or whatever it may be. I find it very difficult at times; it is like walking on eggshells, because in the profession of athletic training everything can change. When you think practice is going to end at 4:30 pm and you will be able to pick your son up at 5:00 pm, and then an injury happens at 3:00 pm, and then you are [in] the ER until 8 or 9:00 pm that completely changes it. So my spouse helps with that by being very flexible. She is an honorary ATC because she is so flexible.

The married-with-children ATs used family time as a means to decompress from their hectic job and shared being “all in” when they were home and with family. Laura said, “I just make sure after a long day that when I am home I am spending time with my son, as opposed to doing random stuff like playing on my phone.”

DISCUSSION

Currently, there is a paucity of literature that longitudinally examines WLB. This is of critical importance in athletic training as the WLB of a majority of ATs working in the collegiate practice setting may be greatly affected by the time of year10 and high in-season demands. Our findings show that organizational factors such as work time and job demands are primary inhibitors to fulfilling WLB for ATs in the Division I collegiate setting. Adding to our understanding of WLB in athletic training, our results reveal that during the in-season period, an AT can be overworked and struggle to find time for personal and outside interests. Another unique aspect of our study was observing that life stage could also affect WLB; conflicts can arise despite the number of roles assumed outside the workplace (ie, being single does not reduce the occurrence of conflict but rather may change its source).

Time of Year

Time-based conflict31 is the major catalyst for WLB concerns in ATs, who work long hours each week to meet job-related responsibilities. Our findings support previous research3,11 and show that Division I collegiate athletics can be a demanding work setting due to the nature of athletic competition. Furthermore, collegiate athletics is defined by competitive seasons during which student-athletes' expectations vary in-season versus out-of-season. That is, when they are in their competitive season (in-season), expectations are high and affect those who work directly with them. Like those ATs who participated in the study of Mazerolle et al,11 our participants had less time to be at home or attend to personal needs and interests during the sport's in-season. Comparably, Eberman and Kanahov16 found that ATs in the collegiate setting wanted more time to be at home and thought their families suffered from their absence due to work-related responsibilities. Travel appeared to be the heaviest demand taking ATs away from their personal and family obligations, as many mentioned this during all 4 interview sessions. In addition to travel demands, the ATs must be present to provide medical coverage to their student-athletes, who want to be able to perform at their optimal levels during their competitive seasons, thereby increasing expectations that ATs be available at all hours through either phone contact or direct contact in the clinic. Although our participants shared that the demands are less during the out-of-season period, they still may work 40 to 50 hours per week. Despite this reduction in hours, WLB may still be affected, particularly due to the changes made by the NCAA and to summer conditioning activities.32 Simply put, the demands of the profession (workload, travel, and direct patient care) do not seem to change drastically, with the exception of travel and the urgency of care, when student-athletes are not in their competitive in-season. Thus, the time-of-year effect seems to be most strongly felt during the AT's competitive in-season; however, because of a small reduction in time demands, the off-season period counterbalances some of the challenges with WLB.

In response to the demands placed upon them both from time and energy perspectives, our participants recognized the need for acceptance and willingness to view their WLB in chunks of time. That is, many of the ATs in our study recognized that the competitive in-season is when more time and energy need to be allocated to work roles, not to personal or family roles. In essence, our participants are accepting of the athletics lifestyle and the inconsistencies associated with the hours worked throughout the year. Lazar et al (unpublished data, 2016) found that this concept of acceptance was a facilitator of career longevity, as the AT was able to maintain balance and commitment by being flexible and cognizant of the demands of the profession. In fact, collegiate athletics is well known to be a demanding work setting that requires personal and family sacrifices,18,26,33 but planning and adjusting to the responsibilities of the workplace34 allow the AT to view them as effective coping mechanisms and a way to remain balanced over time.

The participants demonstrated signs of resiliency, a characteristic associated with effective coping and the ability to manage high levels of stress. Individuals who exhibit resiliency often possess effective communication skills, are problem solvers, enjoy helping others, and have support networks.35 Many of the strategies discussed by our participants seem to parallel these attributes associated with resiliency, such as having activities to look forward to; demonstrating a positive, accepting mind-set; and having support networks in both the workplace and home. Resilience, in fact, is a fundamental aspect to maintaining WLB and professional enthusiasm.36 Furthermore, the literature37 suggests that developing a resilient culture within the workplace can reduce negative stressors and improve quality of life for the individual. Resilient workplace environments appear to foster positive relationships among coworkers and exhibit support and sharing of similar views, attitudes, and behaviors. This is probably the case for our participants, as they, like the participants in the study of Mazerolle and Goodman,23 described support and teamwork as coping mechanisms for stress and finding WLB. Furthermore, resiliency, much like WLB, is developed and confounded by individual and organizational factors. That is, an AT must possess emotional intelligence (the ability to understand his or her own needs and an awareness of others' needs), effective coping skills, and optimism and realism to handle stress. Resiliency is also cultivated when collegial relationships are supported within the workplace and members of the workplace communicate effectively with one another.

Organizational Demands

Our findings regarding factors contributing to difficulty finding WLB in the collegiate practice setting are not novel, yet they continue to showcase the demands of a competitive, intense workplace environment.33 Athletic trainers and others in similar fields, such as coaches, sports informational specialists, and strength and conditioning coaches, face demanding workloads regardless of the time of year. This is due in part to growing expectations of student-athletes, which proportionally affect those who work with them. A 2008 NCAA report38 on collegiate coaching and administration revealed that 75% of coaches and administrators in the Division I setting recognized that their careers in athletics conflicted with family duties. Although similar data are not available for the field of athletic training, the outpouring of research on WLB indicates that it is a concern for ATs. The NCAA, recognizing that today's athletic environment is demanding and that many employed within this setting are struggling to find WLB, developed an initiative to help athletic administrators, ATs, staff, and coaches establish WLB strategies and develop more effective policies and workplace practices that address the needs of the individual when attempting to create WLB. Similar to findings in the literature on athletic training3,13,39 and coaching,28,40,41 our participants indicated that an unrelenting workload, which encompasses hours, travel, and lack of control, contributes the most to their imbalance. This shows that the organizational aspects of the job are foundational to WLB concerns for ATs.

To overcome the organizational strain placed upon them by the nature of their professional role in the collegiate setting, our participants relied on support garnered within the workplace. Kossek et al42 described this as cultural work-life parameters, whereby informal processes and means help facilitate WLB for the individual. Simply working alongside individuals who share similar visions, goals, and attitudes regarding WLB allows for cohesion in the workplace, which facilitates WLB. Cultural work-life support is developed not only from the relationships forged with coworkers but also from support and recognition from supervisors that engagement in caregiving and other nonwork roles can provide mutual benefits; this concept, called role enrichment, posits that success in 1 role can spill over into other roles.43 Our findings regarding support networks are not unique but continue to demonstrate, like those of others before us,10,39 that having organizational support, including support from coworkers and supervisors, can be fundamental in achieving success as an AT in the collegiate setting and finding time to be engaged in other aspects of life.

In previous research,10,13,39 ATs described the need for their coworkers to be willing to share in job duties (eg, cover a practice so they can attend a wedding), for their supervisors to be supportive of nonwork and family obligations and willing to allow ATs the chance to fully participate in those roles without consequence, and for a workplace environment that is viewed as family friendly. Our results were similar; however, we also found that it was necessary for ATs to communicate their personal and family needs as a means to fulfill WLB. It was apparent that by communicating effectively and often, our participants were able to satisfy their WLB needs, as they could plan ahead for a day off to attend a wedding, have the oil changed in their car, or watch their son play football. Overall, the descriptions provided by our participants illustrate a cultural work-life support system that exudes organizational support—a fundamental aspect not only for the development of WLB but also for professional commitment and job satisfaction.28 Organizational support, especially for ATs employed in the collegiate setting, is of utmost importance, as over time the demands of the profession can lead an AT to consider leaving15,19 because of the lack of perceived WLB amid other influences.

Life Stage and Demographics

It is often presumed that those who are married and have children, typically younger children, are at greater risk for problems with WLB. These additional personal roles are often thought to increase both the time demands and the stress placed upon the person and make him or her susceptible to work-life conflict. However, these predispositions are no longer considered the only barriers to WLB, as the landscape of the American family has evolved and the perceptions of what is considered acceptable as important personal roles have grown. Mazerolle et al19 found no sex or relationship differences among ATs in the collegiate setting, and since this study, these differences were rarely noted in athletic training.10,11 Much like previous authors, we did not identify any true differences; that is, our male and female ATs did not appear to experience greater WLB challenges because of their sex but rather it was the source of the conflicts that differed among the life-stage groups. For example, our single participants struggled to find WLB, as they often had to manage personal and domestic responsibilities alone and did not have a spouse to provide support for necessary but time-consuming tasks (eg, laundry, grocery shopping). Our married and married-with-children ATs, despite having someone at home who could manage the day-to-day tasks and housework, felt pressures to be present at home with their spouses and children and to be as involved as possible despite demanding work schedules. Simply stated, role conflict is a primary source of WLB concerns, as often the demands in a person's roles (eg, life, home, work) are incompatible, and the individual must try to find the time and energy to navigate these roles.44 So WLB difficulties arise for ATs not because they are married or have children but rather because they work long hours, which limit the time available to seek outside roles, such as parent, friend, spouse, or caretaker, or to just take time for themselves.3–5

Creating personal time and having external support systems were the ways our participants managed their various roles within and outside the workplace, which is comparable with the findings of other researchers10,13 who investigated WLB within athletic training. As discussed in the NCAA “Work and Life Balance” initiative, setting priorities that include personal time and finding support are key to creating WLB when working in the collegiate setting. The recommendations made by the NCAA align with the NATA's position statement7 on WLB, which suggests that ATs need to use priority-setting tactics that include viewing personal and family time as aspects of life that are as important as work and making sure to not neglect those needs and interests in favor of work-related responsibilities. More often, ATs consider their own needs secondary and attend first to the wants and demands of their student-athletes, coaches, and other coworkers. This sacrifice is likely due to a combination of factors, including the personality of the AT and the culture of the sport setting (ie, expectations to be present at all times).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study was the first in athletic training to present findings related to WLB from a longitudinal perspective. We recognize that our study gained the perspective of only a small group of ATs working in the collegiate setting, but it was purposeful because it was exploratory. Departure has been a primary concern for ATs in the collegiate setting and the major influence for our sample population. Future authors need to include participants working in a variety of practice settings, over time, to fully appreciate whether time is as influential a factor on WLB for all ATs or if this is isolated to the collegiate setting. Also, focusing on the collegiate setting sport assignment may play a role in WLB over time; that is, WLB could depend on whether ATs have multiple assignments or sport types. Other concepts, such as professional enthusiasm and commitment, job satisfaction, and burnout, may also be affected by time; however, we did not fully explore these concepts in our study. Furthermore, our study was qualitative in nature, and thus, did not quantify the level of WLB experienced by our participants. Future investigators should explore the influence of time of year using a mixed model to triangulate our findings as well as to fully appreciate WLB and other professional concerns in athletic training over a broader perspective. Personality and other individual factors are beginning to emerge as aspects that can affect WLB and other professional topics, yet little is known about these factors. Resiliency seemed to be a mediating factor for WLB in these ATs; thus, we suggest that future researchers take a deeper look at personality traits such as affectivity, resiliency, and hardiness to explain the WLB interface in athletic training. Finally, we recognize that our participants were relatively young. This is a common demographic for this practice setting, but future authors should include a greater age range to determine if other factors can influence WLB over time.

CONCLUSIONS

Our purpose was to gain a greater understanding of WLB in Division I ATs by examining the construct over time. Our method was unique and essential to learn more about factors of conflict contributing to work-life imbalance for ATs. Several implications can be drawn from our findings. Work-life balance inhibitors are affected by the time of year, specifically the competitive athletic seasons. Our participants used supervisor and coworker support to help them through the more demanding times of year. Additionally, we found that regardless of life stage, our participants experienced some conflict between their work and personal roles; the main difference was what they perceived as demanding their attention in their personal lives. A better understanding of how time affects WLB will help organizations establish better retention strategies.

REFERENCES

- 1. The three faces of work-family conflict: the poor, the professionals, and the missing middle. Center for American Progress Web site . https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2010/01/pdf/threefaces.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chittenden EH, Ritchie CS. Work-life balancing: challenges and strategies. J Palliat Med. 2011; 14 7: 870– 874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008; 43 5: 505– 512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA. Examination of work-life balance among athletic trainers in the clinical rehabilitation setting. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2012; 4 6: 257– 264. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pitney WA, Mazerolle SM, Pagnotta KD. Work-family conflict among athletic trainers in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 2: 185– 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Becker-Doyle E. Editorial: NATA sees future in updated strategic plan. J Athl Train. 2003; 38 3: 192– 193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A, Eason CM. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: work-life balance recommendations. J Athl Train . In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football bowl subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010; 45 3: 287– 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A, Pitney WA. Factors influencing retention of male athletic trainers in NCAA Division I setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2013; 18 5: 6– 9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Trisdale W. Work-life balance perspectives of NCAA Division I male athletic trainers: strategies and antecedents. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2015; 7 2: 50– 62. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies that contribute to work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2013; 5 5: 211– 222. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Membership statistics. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site . http://members.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/index.cfm. Accessed September 18, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 2: 194– 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train. 2010; 45 5: 459– 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kahanov L, Eberman LE. Age, sex, and setting factors and labor force in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 4: 424– 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eberman LE, Kahanov L. Athletic trainer perceptions of life-work balance and parenting concerns. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 3: 416– 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A. Strategies for athletic trainers to find a balanced lifestyle across clinical setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2012; 17 3: 7– 14. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict in coaching I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manage. 2007; 21 3: 377– 406. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008; 43 5: 513– 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wright TA. A look at two methodological challenges for scholars interested in positive organizational behavior. : Nelson D, Cooper CL. Positive Organizational Behavior: Accentuating the Positive at Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2007: 177– 190. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Perceptions of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I female athletic trainers on motherhood and work-life balance: individual- and sociocultural-level factors. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 8: 854– 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Fulfillment of work–life balance from the organizational perspective: a case study. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 5: 668– 677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: SAGE Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Athletic trainers with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2011; 16 3: 9– 12. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Naugle KE, Behar-Horenstein LS, Dodd VJ, Tillman MD, Borsa PA. Perceptions of wellness and burnout among certified athletic trainers: sex differences. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 3: 424– 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Groth JJ, Ayers SF, Miller MG, Arbogast WD. Self-reported health and fitness habits of certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008; 43 6: 617– 623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon MA, Sagas M. The relationship between organizational support, work-family conflict, and the job-life satisfaction of university coaches. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007; 78 3: 236– 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part I: the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 82– 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goodman A, Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part II: perspectives from head athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 89– 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jyothi Sree V, Jyothi P. Assessing work-life balance: from emotional intelligence and role efficacy of career women. Adv Manag. 2012; 5 6: 35. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Exploring summer medical care within the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting: a perspective from the athletic trainer. J Athl Train . 2016;51(2):175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Situating work-family negotiations within a life course perspective: insights on the gendered experiences of NCAA Division I head coaching mothers. Sex Roles. 2008; 58 1–2: 10– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Giacobbi PR., Jr Low burnout and high engagement levels in athletic trainers: results of a nationwide random sample. J Athl Train. 2009; 44 4: 370– 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. What is resilience? Public Broadcasting Service Web site . http://www.pbs.org/thisemotionallife/topic/resilience/what-resilience. Accessed May 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109 4: 949– 955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCann CM, Beddoe E, McCormick K, et al. Resilience in the health professions: a review of recent literature. Int J Wellbeing. 2013; 3 1: 60– 81. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gender equity in intercollegiate athletics. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site . http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/GE2008.pdf. Updated 2008. Accessed May 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Career and family aspirations of female athletic trainers employed in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 2: 170– 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrative approach. Sport Manage Rev. 2005; 8 3: 227– 254. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bruening JE, Dixon MA, Tiell B, Osborne B, Lough N, Sweeney K. Work-life culture of collegiate athletics: perceptions of supervisors. Intl J Sport Manage. 2008; 9: 250– 272. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kossek EE, Lewis S, Hammer LB. Work–life initiatives and organizational change: overcoming mixed messages to move from the margin to the mainstream. Human Relat. 2010; 63 1: 3– 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manage Rev. 2006; 31 1: 72– 92. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goode WJ. A theory of role strain. Am Soc Rev. 1960; 25 4: 483– 496. [Google Scholar]