Abstract

The promise of a community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) initiative to build capacity and reinforce assets is realized through a fully implemented Victory stage. This article reviews the process to plan for victory by including its goals in the main action plans and reviews several key activities that comprise the main accomplishments, which might include products for the community and scientific articles and presentations that are coauthored and co-presented; as well as partnered conferences and reflection retreats on major accomplishments and transitions. Because dealing with conflict is an important part of the work of projects in general and of developing victories, this article also reviews strategies to turn conflicts into celebrations of growth that can set the stage for the next phase of partnership development as well as for further partnered research.

Keywords: Community-Partnered Participatory Research, Community Engagement, Community-Based Research, Action Research

Introduction

Victory is the stage of Community-Partnered Participatory Research that uses the good work completed in the Vision and Valley to develop products, share them with the community and academics to disseminate them more broadly, and to acknowledge the groups, individuals and agencies that have contributed along the way (Figure 7.1).

Fig 7.1.

Victory

Victory is also the stage for reflection on what has been accomplished to consider next steps for the project as well as for the partnership, and to acknowledge the community and academic capacity building that has occurred. In addition, at the Victory stage, the partnership works to achieve policy change, as well as to recognize and further promote the leadership that has developed. As a whole, the Victory stage is a celebration of strength and accomplishment, coupled with making sure that what has been learned will be useful and shared for community benefit.

Victory happens throughout the project. Celebration, products and sharing do not just occur at the end. There will be many smaller victories at every step of your journey to complete an initiative. Every successful meeting, every mutually agreed-upon compromise, every completed task is a victory and an opportunity to recognize accomplishment. All victories should be enjoyed and celebrated. In fact, one of the most important tasks of project leaders is to help groups recognize and celebrate victories.

The Victory mindset is an expression of confidence that you and your teammates will agree on goals and will achieve them together. From the beginning of the project, the Victory mindset is a crucial part of success.

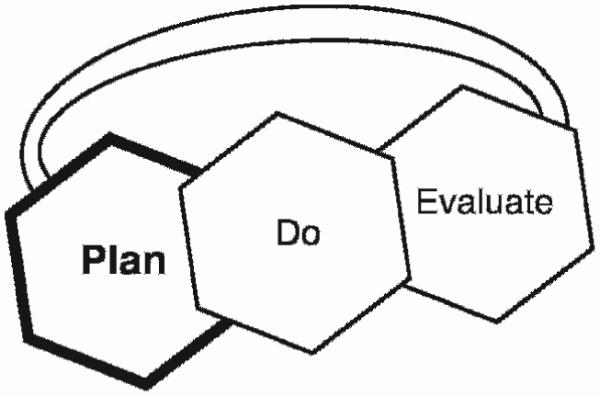

Like the other stages of the project, Victory has three major steps: Plan, Do, and Evaluate. (Figures 7.2, 7.6, 7.10)

Fig 7.2.

Plan

Fig 7.6.

Do

Fig 7.10.

Evaluate

Plan

Planning for Victory starts at the beginning. Each major meeting, the development of the Vision and action plans, the addition of new partners are all cause for celebration. This means that a broad goal of the project at the outset is to develop a Victory mindset, where opportunities for expressing gratitude, pride in accomplishments, and impact are sought, anticipated and recognized.

For example, in developing the Vision, team members should assess the win or victory for each stakeholder to make sure that the Vision is well-formulated to attract diverse partners and to accomplish something of value for each and for the community as a whole.

Throughout the project, project leaders and team members should both watch for signs of progress toward those wins, and set up the project so that those wins are more likely. For example, are partners who want to learn about evaluation included in the Evaluation Committee? Are those to whom community recognition is important given a chance to speak or meet others at community gatherings? Provided that a fair process is set up such that participants have equal chances at serving roles they would like to serve, a project can align its players (or ensure that they align themselves) to optimize the chances of achieving their win. (Figure 7.3)

Fig 7.3.

Win

How does one find out about potential wins for each member? By asking. But remember that at the beginning of the project, trust has not yet been built. So people may not be comfortable sharing some types of goals, such as personal goals. Leaders should be especially cognizant of people during the early stages of engagement, to understand what team members are asking about. Later, as trust develops, direct questions about personal goals or agency goals may become appropriate. Sometimes it is best to find out about wins through what people say about others. For example, one advantage of the Vision exercises we have suggested is that people do not initially talk about themselves or their agency directly, but instead more broadly about what agencies or communities might gain. That information then can be useful in offering roles and discussing advantages with different stakeholders.

Each type of win, personal, agency, and community, can be a cause for a project celebration. But most likely, everyone will agree that the biggest causes for celebration are community wins.

Find Celebration Opportunities

It’s one thing to know generally what wins may be; it’s another thing to find a good opportunity to express appreciation and to celebrate. (There should be some regular celebrations as a group, even if it’s bringing something special to eat to a meeting or giving an individual member a round of applause).

Part of the Victory mindset is victory discovery: being actively on the lookout for events to celebrate.

Victory discovery means that leaders of working groups, Councils and subgroups or subcommittees, as well as individual members, should follow the work by attending meetings, reading minutes, listening to casual comments, reviewing action plans, and following the overall flow and structure of the project to discover what is new and exciting.

Often, working groups are so busy with the work, or so modest, that they are not aware of the very special contributions that they make, as groups or as individuals. Sometimes groups can be highly critical of their own good ideas, even when they have been successful.

For example, in a prior research study, Partners in Care, some of us participated in training dozens of providers all around the country to improve depression care, including training psychotherapists in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for depression. It was quite common for providers throughout the study to express strong doubts about themselves and the work they were doing—they often felt they did not measure up to the standards that they had learned, for example, because of time constraints or local resources available. Yet the study had very positive outcomes. Providers were surprised to learn that, using their Partners in Care training, they had helped people more than they would have without the training. If providers have these kind of self-doubts and self-esteem problems, we would expect many grassroots community members to have such doubts as well!

This means that you might not always be able to rely on the reporting back of working group leaders to the Council, or members of groups themselves, to identify the great ideas that they have or the good plans they are developing.

Leaders must listen to plans and progress, find the accomplishments and give feedback, even immediately. For example, working groups can be given a small amount of resource to support a party or a food treat or have a special guest or go on a trip to a park, as a reward for their progress.

One can also learn about wins and victories that might be happening by watching and listening to the reaction of guests who step into the process. In community-academic partnered projects, there are almost always new members and guests cycling through meetings and events. We have found that these individuals are often surprised at the depth of the partnership, or feel that the community has hit upon an idea that their own agency would like to use. This observation should be immediately shared with the group (look at what our colleague has said about our work!) – and can lead to something bigger, such as special recognition from that agency for community contributions. (Incidentally, if one of your guests expresses strong approval of or interest in your work, don’t neglect the opportunity to develop a new partner.)

Develop Leadership

One of the greatest victories that can emerge from community-academic partnered projects is new leadership for individuals, agencies and the community as a whole. When individuals put themselves on the line and help develop something new, we call that that leadership. When agencies step out of the pack and try something new, we call that leadership. When a community learns how to work across borders, agency and individual lines to try to build capacity for a better community, we call that leadership. (Figure 7.4)

Fig 7.4.

Leadership example

Many people do not see themselves as leaders and may not have had many opportunities for recognition of their leadership. They might not think of a community participatory action group as a leadership opportunity. However, community and academic co-leadership of working groups or committees presents many development opportunities for community and academic members.

Examples of leadership activities include leadership in developing and implementing action plans; representing one’s agency in an initiative; speaking at an event; sharing one’s own personal story; suggesting resources, such as referral lists or agencies for partnering that are available in the community; or even helping to organize refreshments for meetings. These opportunities, if recognized, can build members’ confidence.

Here’s another example. About two years into the Witness for Wellness project, member attendance at meetings dropped dramatically. A community leader in the project made a number of calls to see what was going on. We were afraid the reason might be negative (loss of interest in the project). But instead it was positive; many community members had new jobs and couldn’t participate during the day. Many of them had previously been out of work for some time. Of course we do not know for sure if their participation in the project helped them get jobs, but we can certainly say that we observed their growth in confidence and leadership skills over the course of time. And, we moved the meeting time to accommodate their new schedules.

Mentoring

Mentoring is a responsibility as well as a pleasure. CPPR projects should incorporate mentoring at all levels throughout the project. Established members can mentor new recruits. Council leaders can mentor working group leaders.

Mentoring should occur within and across community and academic lines. For example, senior community leaders should mentor academic partners in understanding community values, language, and issues, responding to conflicts, and even recognizing whether or not there is a conflict (passionate feelings and discussion should not automatically be viewed as conflict). Academic partners can mentor community members in understanding some of the options for evaluation and what the literature reveals, as well as theoretical or clinical issues involved, and academic procedures (such as meeting the requirements of institutional review boards). Junior or new members will require mentoring in the project rules.

Seasoned mentors from community and academic stakeholders in the project should mentor, individually and in groups, with the goal of helping potential new leaders to understand how to partner and rely on each other, and to understand the operational principles and project structure that keeps things moving forward. Special skills are a real asset and can be used in mentoring. (For example, the Witness for Wellness project was enriched by the presence of some individuals skilled in writing grants and some skilled in writing poetry – and we were equally grateful for both.) Just about anyone in a project at any level can mentor at least one other person in the project about something related to the project, using skills they know and enjoy, eg, cooking, reading, use of a different language, and so forth. Pairing mentors and using them well strengthens the bond between mentor and mentee and builds up a sense of victory.

Special Recognition

Project leaders may have roles in their institutions or organizations that allow them to develop recognition opportunities for the project and for its members. Senior academic leaders, for example, may be able to facilitate joint presentations of the project at national meetings, giving community members a travel opportunity as well as wider recognition. Senior community members may be able to develop community presentation opportunities, new partnerships, or actual job opportunities for community members. Leaders should be encouraged to think through the project goals in relation to their contacts, and what they can do to enhance recognition and impact.

Develop Funding

New opportunities for additional projects will require funding. Developing funds means developing a proposal, which requires substantial lead time and possibly additional time for resubmitting the proposal after responding to reviewers’ comments. Obtaining funding for a new phase or component of work is in itself a major project accomplishment and an excellent opportunity to celebrate a victory.

Both community and academic partners may be aware of potential funding opportunities that relate to the central project goals. Project leaders and especially Steering Council members should seek to learn about funding opportunities, for example through reviewing announcements from local, state and national foundations; federal, state, and county governments; or pursuing private philanthropy.

It is important in developing funding to emphasize the diversity of the partnership, and particularly the need for funds for community partners. Academic partners may have the most grant-writing experience (but not always: some community partners have extensive experience). So it is important to consider jointly how the funding is developed, who leads, what the terms of leadership are, and all the other issues spelled out in the operational principles of the partnership. (Figure 7.5)

Fig 7.5.

Funding tip

Other forms of preparation include discussing project ideas with funding agency representatives, learning about the types of proposals they fund, seeing examples of proposals, and reviewing ideas for different ways of developing the project with community members and academic colleagues.

Pilot data or preliminary studies are important to show feasibility and potential of the project to succeed. For this purpose, project documentation that has already been developed – the Operating Principles, Vision, Action Plans, and progress to date, such as any sponsored events or survey data, can serve as preliminary data to show the promise of the overall project.

Funding can be difficult to obtain. Our recommendation: do your homework before trying a new funding agency. Get to know the agency, learn about its work and mission, and attend meetings that it offers to see what kind of work the agency tends to support.

Build Relationships

No discussion of planning for Victories is complete without a discussion of relationship building. Victories are built through programs and activities that depend on strong relationships.

Fortunately, there will likely be some people involved in the project who like to organize events and set up games and activities that are fun and engaging, and to reward others. Having a social chairperson or rewards activity or Victory chairperson can all be ways of building rewarding activities into the project infrastructure. Find the right opportunities and put people in a position to use their gifts to help yield celebrations that are not only enjoyable in themselves, but are also the building blocks for future Victory.

Celebrations as Action Plans

The project can and should have action plans concerning celebrations, although spontaneous celebrations are also important.

Action plans can focus on developing relationships; sponsoring events; creating products; and appreciating and celebrating teamwork. All of these are related and part of the Victory mindset for team members and leaders.

Let’s celebrate that!

Do

Document Programs and Products

One of the key features of community-partnered participatory research projects is the emphasis on documentation and sharing of programs, findings, stories and materials. Without documentation of what happened, what worked and why, effective dissemination, the central activity of the Victory phase, cannot occur. Documentation can be through the written word, visuals, recordings, or passing down through an oral tradition, Internet postings or other means. Documentation enables the project to establish a tradition and leaves something for the team and the community that can be sustained. Documentation allows the project team to share the project and products with others, including community members and agencies, other communities and scientific groups (Figure 7.6).

Reaching different community stakeholders often requires different forms of documentation, specifically tailored to that particular stakeholder group. For example, sharing a program that is designed to support clinics in providing culturally competent care may require a manual or toolkit and either an audio or visual presentation, or a team of leaders to provide training, or a combination. Reaching a scientific audience often requires a published scientific article and presentations. Reaching a policy audience might require a policy brief or publication in a policy review journal and presentations to policy audiences. Such presentations might benefit from stories from the community as well as more formal findings of the project. Reaching community members might mean using a magazine article or local newspaper or radio show, or sharing in other ways such as posters or in-person presentations at a local mall.

Each of these entities requires developing a different kind of product, and different kinds of strength and skills in developing the documentation. In addition, different partners may be needed to open up the opportunity, for example, to access a venue or to provide technical support for that mode of documentation.

Developing documentation means determining who the target audiences are for the document, determining the strengths of the partnership for developing different products, making partnerships to support them, and implementing that strategy to create a finished product.

As in all other phases of community-academic partnered research, all of these phases should be implemented using a partnered approach. That means the decisions about what should be documented, how and for whom, require the working groups and Council as decision-making bodies. This may involve a period of capacity building to enhance the skills of all decision-makers.

For example, academic partners will likely be the most familiar with academic documentation venues and styles, such as presentations at scientific meetings and publishing of scientific articles. Community partners may be the most familiar with venues for the general community, such as which newspapers are read in the community, and the appropriate language and style. Different group members might have ideas about other ways of documenting, such as hosting poetry-reading sessions on the topic with guided discussion, or having a photography exhibit or showing a film and hosting a discussion. There are also existing methods of conducting and presenting blended scientific and arts documents through community participatory research methods, such as photovoice or video-voice.

A general sequence for developing documentation and products is:

Decide on the audience you want to reach.

Decide what kind of product will be effective for that audience.

Develop the partnerships and technical expertise for that product.

Draft and revise the product.

Publish, present, or demonstrate the product.

Acknowledge the accomplishment through a publication party or other celebration open to the partnership and the community, or certificates of appreciation for contributors (as well as authorship or acknowledgements, depending on the kind of product).

For instance, one goal of the Los Angeles Community Health Improvement Collaborative was to develop and demonstrate our partnership’s capacity for partnered research, to set the stage for larger community projects and grants for further work. The partnership and each initiative within it discussed the kind of target audiences for the work and considered community and academic objectives. We developed community, academic and blended objectives.

An example of a community objective was developing a proposal for community-based programs to improve mental health and promote wellness among African Americans in South Los Angeles. This effort involved developing a joint proposal for funding a planning initiative for those centers.

An example of an academic objective was planning scientific papers on the development of the Collaborative and on the progress for each pilot effort within it for publication in a special issue of a scientific journal.

An example of a blended objective was the development of a community art exhibit and poetry sessions, which were intended to result in research papers as well as the immediate community benefit of the exhibits themselves.

Our product-development steps for each of these three examples are described below.

Community Objective: Partnered Proposal for Community Planning

Determine the intended audience

The intended audience for the planning effort arose from the working group discussions of Witness for Wellness, which expanded post-Katrina to a discussion of how to conduct outreach to displaced families from the Gulf States who had been evacuated or otherwise displaced to Los Angeles. The target audiences initially arose from the community priorities but became joint community and academic priorities through the partnership.

Determine the product

Through collaborative discussions, we felt that developing a sustainable infrastructure for community wellness centers would require a planning grant process. We searched for opportunities to submit a planning grant, and approached several large foundations with a history of supporting community, academic, or community-academic efforts.

Ensure partnership and technical expertise

We decided that to successfully conduct outreach in new ways to persons of African descent, we needed to expand our partnership in two ways: securing partnerships from provider groups experienced with providing services to underserved communities and persons of African descent; and partnering with community-trusted organizations such as churches and other faithbased organizations. Community members suggested potential partnering organization; joint meetings involving community and academic leaders helped build those new partnerships. We also attended meetings and conferences in the community to identify and develop relationships with potential organizations.

Draft and revise the product

We drafted a proposal that was circulated extensively for feedback. The proposal title and mission was changed to more closely reflect community priorities. In response to feedback from the potential funding agency, the proposal was divided into two separate proposals with somewhat different partners, one more related to the evacuated Gulf States populations and one more related to the South Los Angeles community.

Publish, present, or demonstrate the product

Since this was a proposal and not a program or product per se, the funded planning proposal was used to draw the potential new partners together and initiate a specific partnership to implement the planning phase.

Acknowledge and celebrate

This successful funding of a long-standing community goal (or at least the planning phase) was a cause for celebration for the Witness for Wellness working groups that supported its development. It was also meaningful for the new partners and their communities, who came to that project through a separate path and history. We joined together in a new program with its own purposes for program planning.

Academic Objective: A Special Journal Issue

Determine the intended audience

The Community Health Improvement Collaborative wanted to share its approach and develop its reputation for work within the scientific community interested in health disparities and interventions to address them. This was a shared goal with community members, who had less experience with this audience and were intrigued, but somewhat intimidated by the idea of publishing scientific articles.

Determine the product

We considered publishing separate articles on different subjects, which can require intensive efforts and months or even years to complete. In addition to the significant time requirement, the separate article strategy would have also risked not showing the inter-relations of different components to the whole Collaborative. We finally decided on a series of articles, all published together in one issue of an academic journal. In addition to meeting the goals of the partnership as a whole, this approach also encouraged junior researchers by allowing early publication of results.

Ensure partnership and technical expertise

We approached an editor of a scientific journal interested in health disparities and negotiated a special issue. We determined the funding that would be required, and then collaborated in identifying resources across the different centers and institutions supporting the Collaborative. We selected a pair of editors and collaboratively identified potential papers. We sought community co-authors on every paper (including as lead author on some).

Draft and revise product

To facilitate community participation and redirect power according to our operational principles, we developed mechanisms as a group to assure an equal community voice (academic participants tend to be much more familiar with writing papers). We set up conference calls and meetings to frame the subject. We identified staff to be available by phone, e-mail or for a personal meeting to record ideas. We offered tape recorders. We developed a pool of funds to pay community members to review project data and minutes of meetings, and asked them to develop summaries of different project components. These were integrated and edited either by a research staff member or by a team of staff and community members. We asked community members to write or talk into tape recorders or to staff, to share their experiences with the work, and we selected quotes about their perceptions and experiences to include in the articles.

Not surprisingly, there were disagreements along the way as to what had occurred in groups and as to partnership processes or accomplishments. In deciding how to present those disagreements or resolve them, we chiefly sought to make sure that the diversity of opinions was fairly presented, and to reassure members that differences of opinion are a strength and are to be expected when diverse views are joined. We experienced growth in community and academic partners through this rigorous method of developing jointly authored papers.

Publish, present or demonstrate

The journal issue was published.1 However, we also wanted to share the papers broadly with community and scientific audiences. We negotiated with the journal editor permission to purchase extra hardcopy issues as well as a large number of CDs with the full set of articles. In addition, we developed a website on the partnership and included PDFs of all the articles on the website. We generated a list of community and scientific leaders and partners and sent a copy of the hardcopy version or the PDF to everyone on the list. We collaborated with one of the academic institutions to develop a newsletter about these new products and created links to the products on the website of community and academic organizations.

Acknowledge and celebrate

The publication and dissemination of this special issue of a scientific journal was a landmark event for the Collaborative and for the members of each project represented. The community leads of one of the papers hosted a party to celebrate their paper and the special issue. Presentations were made at community and scientific conferences concerning the findings.

Blended Objective: Community Arts Events

Determine the intended audience

The community selected the intended audience as attendees at the Pan African Film Festival in Los Angeles, a large gathering that historically attracts thousands of people. Our goal was to highlight the importance of depression as a prevalent (but often hidden) health problem.

Determine the product

The community selected the artistic events, including photography on community sources of stress and resilience by group members; spoken word and comedy acts inspired by the theme of overcoming depression; and a film on the impact of the history of slavery on communities of color today. Academic members worked with community members to develop evaluation designs and measures, which were jointly fielded at the Film Festival.

Ensure partnership development and technical expertise

Event preparation required developing a partnership with the office sponsoring the film festival as well as collaboration with local artists. Local artists interested in the project mission (overcoming depression) were invited to join the main working groups planning the event. Media evaluation experts were called upon to support the academic members of the working group in developing appropriate design and measures, and were invited to speak at the working groups.

Draft and revise product

The feasibility of Spoken Word (a spoken poetry event including spontaneous audience response) was pilot-tested at a local, respected venue for Spoken Word. Artists were engaged to select or develop new poems for the event. Comedians were invited to meet the group or read background information to better familiarize themselves with the core issues in the Vision. Photographs were developed by the group and reviewed to select candidates reflecting positive and negative influences on mood/resiliency. A marketing strategy for events was developed.

Publish, present, or disseminate

After much logistical planning, the events occurred, including their presentation and evaluation, over a two-week period of time. As a record of the events, photographs of events were taken and used in presentations along with survey data from the evaluation. (Figure 7.7) (Note: The survey questionnaire was a focal point of many meetings; see the example below.) These data were used in an academic-community co-authored publication that was accepted for publication.2

Fig 7.7.

Blended objective example

Acknowledge and celebrate

Several forms of acknowledgement and celebration were used for the participants in these arts-and-science events. One of the poets involved published her own poetry book, and we hosted a celebration and reading of several of poems by the poet. We provided honoria for some community and academic coauthors for major partnered research projects. Community members hosted a celebration for publication of the coauthored scientific manuscripts. For several of our Victories, we have found that local politicians are often very willing to recognize community work by issuing citations of merit for key meetings or other products and accomplishments. (Figure 7.7)

Disseminate: Presentations and Conferences

There are many ways of disseminating products and findings. Two of the most common, besides publications or exhibits (discussed above), are presentations and conferences. Presentations and conferences represent important opportunities to disseminate the work and findings through equally shared, public meeting opportunities. (Figure 7.8)

Fig 7.8.

Multi-partnered research conference example

Co-presented, community-academic presentations are not new to community-based participatory research, but they are relatively unusual in medical research settings, such as scientific conferences focusing on clinical research. Such conferences sometimes have presentations from community members to share a community perspective or show a broader partnership with the community, but routine co-presentations are more unusual. However, some of the leading community-academic partnerships do them routinely (such as the Detroit partnerships3).

We developed presentations as equal partners through the Pre-Term Delivery Workgroup in partnership with the Center’s for Disease Control and Prevention, the Community Health Improvement Collaborative, RAND Health, Witness for Wellness, presentations for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Clinical Scholars Program, and other opportunities. For example, one of our senior researchers won a national award for research in his clinical discipline and included a senior community partner as a co-presenter, the first such partnered presentation in this research award series. While we have not perfected the art of shared presentations, we can offer a number of recommendations and suggestions based on our history.

Partnered Presentations

Information to be shared from a CPPR initiative includes your mission, process, successes, obstacles, and results. A good rule of thumb is to share anything that will affect the stakeholder community or that originated with the community. An effective format for informing and involving the broader community is an in-person presentation. The same is true of scientific presentations, as an in-person partnered presentation speaks volumes about the value of partnering.

Negotiating a Partnered Presentation

Unless you have a reputation for partnered presentations and are asked for that specific purpose, you are likely to receive an invitation to present as an individual, either as a community presenter for a community audience, or an academic presenter for an academic audience. You are most likely to be invited to speak alone. There may be travel and an honorarium involved. The host organization is commonly not looking for opportunities to spend more money by inviting more than one person. So, what do you do?

The first step of a partnered presentation is negotiating the ask for a partnered presentation. That means turning an individual invitation into a partnered one, and then determining a solution that is feasible and that will work for the venue. We have usually handled this by reviewing the options for individual and partnered presentations with the inviter, and what they are likely to involve. Most often, the inviter is intrigued by the idea of a partnered invitation, but a big issue leaps to the fore: will the inviter have to pay for two presenters?

The ensuing negotiation can be quite interesting. Sometimes we suggest using the honorarium for a single speaker to cover the travel for a second speaker, and we absorb the lost honorarium. Sometimes one of the sponsoring organizations, recognizing the value of this kind of presentation, commits to additional funds. Sometimes we are able to work the travel into an extended visit for personal reasons (to see family, for example), so the issue of an honorarium is not so important. Usually, the partnered presentation can be negotiated, but one should try to be aware of the implications for the presenters and for the inviting organization.

In any case, we expect both presenters to be treated equally – to have equivalent accommodations and to be paid equivalently.

One particular issue for travel with community members is that asking the inviting organization to front the costs of travel (airplanes, hotels, food) is unrealistic. So we try to figure out strategies to either cover expenses in advance or to have other attendees cover those costs (and subsequently be reimbursed for two). However, some organizations may not support this approach; it’s important to check in advance. It can be a sensitive issue; community members may not be comfortable explaining their financial status and why they need some help to cover costs up front, so it is important for academic partners to ask discreetly and then explore options with their institutions or funding agencies.

Preparing a Partnered Presentation

In community-academic partnered projects, partnered presentations are a requirement. We maintain a mechanism whereby the Council or Executive Committee has to approve the presentations and is informed of who is presenting what and where. If data are being presented, particularly for the first time, this also requires special approval. It is not uncommon for partnership members to forget about the approval requirement until close to the due date (although of course we try to avoid this situation!); in this case, Council members try to approve quickly, but we do insist on approval. For major presentations of new material, we usually request that presenters brief the Council or Executive Committee in person in advance, so that the presenters have the full support of the project leadership for how both the partnership and its findings are presented.

Very often, different audiences (especially community and scientific) have different expectations of presentations. Academic presentations are often factpacked, dry in style, and lacking in stories and context. Community presentations are often the opposite, full of stories and more like a sermon or dialogue with the community, sometimes with jokes or songs or other engaging elements. What to do when two worlds of communication collide? Over time, we have worked to fit presenters’ styles and the messages to be delivered. We divide the presentation time to fit the experience level of the presenters, our sense of expectations of the audience, and the stage of engagement of the partnership.

For example, we encourage community presenters to use their own style and academic presenters to use theirs. But we also encourage presenters to learn from each other and even practice presenting each other’s materials (sometimes to hilarious effect). For example, one senior community presenter uses visual analogies, like an actual wedding ring, to represent engagement, and asks academic partners to propose during presentations. One academic partner asks his community partner to present formal results slides. If partners are new, we may ask them to introduce themselves or each other at the outset, almost in a talk show manner. These unexpected openings and presentations can make their mark by surprising an audience but also showing a partnership that is real and interested in conveying the results.

Presentations should give an overview of the project, the history of partnership, the structure, our stage of development, and findings to date. At each juncture, we try to find ways of making the community meaning apparent, whether by giving quotes or showing video clips from community conferences, or slides of events and artwork, or pictures of the community at work. We often share the tools we use to equal the playing field or ease conflicts, like the “Circle of Stars” (see below under “Turning Conflict into Victory”, Figure 7.9) or the puppets we use in meetings and retreats. Sometimes we act out skits to show how we have handled conflict or gone through stages of partnership development.

Fig 7.9.

A Circle of Stars

Responses to these presentations are generally positive. We couple more playful presentations with in-depth material on the principles and models that we follow, so that people get the points of the stories, examples, and tools we have used.

Making the Presentation

In most situations, we try to give partners equal time. We divide up the presentation, although we also encourage partners to help each other out and step in with examples or corrections, to show an active partnership at work in real time.

We avoid stereotypes. For example, we think that it is a mistake to treat methods and findings as something academic partners must present, and background, context, or interpretation as something suitable for community partners to present. We mix and match, because the work has been partnered, and we want to illustrate the two-way capacity building that is central to community-academic partnered research.

We also do allow some unpartnered presentations. Senior community partners present and teach about community-academic partnered methods. Senior academic partners present and teach about methods, design issues, and strategies to engage and retain academics in partnership initiatives. Most of our partners have other professional work and lives, and not all of it represents partnered research— and they of course present about those matters too. However, whenever possible, we encourage them to include a section of those talks about their community work. In those settings, the partnership and partners should be acknowledged (for example by a slide) and the Council should know even about these smaller opportunities, since they also represent a project accomplishment.

Related Activities: Partnered Visits

Presentations often are accompanied by other activities, such as meetings with members of the agency, community members, or faculty. This is especially true of visits to out-of-area institutions.

It is best to think through the scope of such a visit and how to handle the inclusion of both partners in main activities. A good option is to offer partnered seminars or consultation sessions. Individuals seeking consultations from one partner only may be best handled at a separate time or by phone or mail, unless both partners have some individual and some joint sessions, but such complicated arrangements can be difficult for the sponsoring institution. So it is important for the visiting partners to discuss their expectations and work out such matters in advance, and explain their style of visiting to the host institution, particularly since the host institution is unlikely to have extensive experience with partnered visits.

Related Activities: Partnered Community Presentations

Because the partnership hosts community events, the leaders also have the option of developing and planning partnered presentations for these community events and conferences, especially locally. Such presentations can be used to build knowledge of the partnership and interventions locally, recruit more partners, or set the stage for broader dissemination or financial support. These are all important objectives for the long-term future of the partnership, and merit careful planning.

To set up a planned, partnered community presentation, first review the stage of the initiative, what you have to share, and the audience you wish to reach. Ask yourself “Who do I want to hear this?” and “Who is going to be directly or indirectly affected?” Then, recruit both groups of people.

Think of the future of the project as well as the present. For example, you may want to make sure to invite some potential funders as well as people who can make a difference in the community in using the products of the initiative, both now and in the future.

Your invitations and efforts to reach your audience can include both more general marketing (sending promotional information and invitations) and directly through one-on-one communication (ie, individual letter, phone, on in person). You will probably need to do one-on-one follow-up for people you really want to be there and for policymakers or community opinion leaders. Be sure to let your prospective audience members know how the intervention would affect them and how their input will contribute to the process. No matter what format(s) you choose, two factors are extremely important to success – getting the audience you want and having community members who have been contributing to the project involved.

Be sure to involve community members from the working group in presenting any data that are shared with the community. A community presentation forum is an opportunity to introduce community members who have helped out to other community members, and to give them recognition for their hard work. For example, you can host a reception for the working group members. This allows policymakers to meet and thank those who have developed a special initiative for their community, offering a public opportunity to policymakers and appreciation to working group members.

Turning Conflict into Victory

Partnered projects involve fairly regular and intense interactions, often around issues about which people are passionate (health disparities, for example). Tensions are natural in this environment, and dealing with emotions and relationships is a key part of community engagement.

Sometimes it is easy to feel overwhelmed by tension and conflict. However, in community projects, it is very important to recall that emotional tone and passionate feelings, even anger, are clues that something important is happening and that people are engaged. A partnered project is unlikely to be damaged by passion. It is more likely to be damaged by apathy (such that people are not able to come together around important issues), or misdirected resolution of tensions (such that people do not support each other or alienate or exclude each other). Those are the true signs of damage that need immediate attention.

Those true signs of damage – apathy, alienation, exclusion – should be addressed directly, by asking all parties what is going on, pointing out the behavior or actions that seem to be problematic, and seeking broad opinions in the working group and Council about how to address the problem. Sometimes, individuals need support or discussion and occasionally, the goals of the project may need to be revisited. Rarely, people need to leave the project for a while to attend to issues in their lives. The “on and off the bus” model of flexibility allows people to engage in the project without overwhelming their lives.

However, genuine disagreements among leaders, or differences in views and communication styles that are hard to see through and may seem to stalemate the project, often contain important clues about something in the project mission or work that needs attention, or may parallel a barrier to resolving the issue in the community. In such cases, open discussions are needed to restore the leadership partnership. But how? Recognizing that people can be hurt even if they agree but say things in anger, or simply stop listening to each other, we have developed various strategies to keep an open dialogue while sharing difficult views. These strategies include the use of simple devices to help maintain the connection through the discussion.

For instance, the “Circle of Stars” (Figure 7.9), allows truly different views or perspectives to be expressed while having fun, or releasing anger, or expressing affection, in ways that keep those expressions within the bounds of friendship and leadership roles. We have shared our Circle of Stars tips with leaders at the highest levels.

We also use puppets to say things that are hard to say, and to show reactions and feelings, which if said directly and in the heat of the moment, might hurt, but if said playfully and indirectly, are felt quite differently so that the partnership is maintained.

We often do this work around a meal, which tends in and of itself to so lessen the tension, allowing us to talk about the project work and move past differences or hurt feelings.

The best solutions, however, are when we can develop insight into how a conflict or apparent conflict is a project victory.

On one occasion, for example, working group members discussed what they felt was racial insensitivity by a senior leader. The discussion took place openly in the senior leader’s presence. Rather than being offended, the leader viewed that moment as a breakthrough moment of trust, completely turning the project leadership into a new direction and increasing the community engagement in the work.

Reflection Retreat

Because of the complex issues in doing work across agencies and diverse groups of people, and the need to have perspective and pull together as a partnership, it is helpful to have periodic reflection retreats. These are especially useful if held in a setting that is away from the immediate environment of the project, like at a park or church or the beach, but where the group can also have some isolation and private time.

At these retreats, project leaders or working group members often begin by reintroducing themselves and talking in a personal way about why they are there and what the project has meant to them in the context of their lives. In one such retreat, we facilitated this by having a puppet on each table – people could speak themselves, or through a puppet. The results were astonishing, with academics and community members sharing their thoughts in a very real way, on an equal playing field, and staying close all the time to the project mission and purpose of the retreat. Another device we use frequently is to ask people to sit next to someone they don’t know well. We give the group five minutes to talk in pairs. Then, each person introduces their partner to the group.

After this kind of ice breaker, working groups reflect on what they have done and what they would like to have done. We often have one or two facilitators who move the discussion forward and help members who are less comfortable speaking to share their thoughts.

Then the group breaks into discussion groups (making sure they include people from different working groups), to think about larger questions like:

What have we accomplished?

How strong is the partnership?

Where are we going?

What’s our potential?

Are we serving our community?

The responses are written on large tablets which can be taped to the walls and then summarized by each group using a community-academic pair of reporters.

A closing discussion and closing activity, such as forming a large circle and throwing dreams for the project into the middle, can bring the retreat to a thoughtful close.

Evaluate

Document Accomplishments

A primary task of the Evaluation Committee and Council is to support the documentation of project accomplishments. This can be as simple as keeping records of meetings, training sessions, attendance, and feedback, or as elaborate as tracking outcomes of main interventions (depending on project goals and resources). Development of partnerships, number of individuals participating in groups, and outcomes for individuals and organizations in that process, are also important to document. (Figure 7.10)

A good starting point for documenting accomplishments is to review the logic model (the flow of planned activities to outcomes), and to identify important accomplishments that should be monitored. Next, review the action plans for what is planned; and then monitor the progress of the work through minutes or other notes taken during meetings, to identify both modifications to those plans and to document completed plans.

This activity involves monitoring a set of action points, such as events, pilots of interventions, or partnership expansions. Use attendance sheets, notes of what actually occurs in events, and feedback from participants such as pre- or post-knowledge surveys, or documentation of programs used, to record outcomes.

Relationship development and partnership can be documented through attendance logs if people identify their agencies, or through more formal partnership surveys.

These sources of evidence for impact and accomplishment can be turned into summary information and used for community updates or graphed on a timeline of accomplishments. And, of course, they are cues to Victory celebrations. In fact, an Evaluation Committee can even be asked by the Council to track celebrations or to use accomplishments and a timeline to determine when celebration is due or overdue.

Prepare Findings for Publication

Another key evaluation task at the Victory stage is to provide support, through a partnered research framework, for the presentation of findings for the reports, articles, and products of this phase. For this part of the task, the project team should review the upcoming planned or proposed products, review the findings, support meaningful and accurate data presentation, and work with other members of the partnership to understand what options may be for uses of data.

Here again, both community and academic input are important. The discussion should focus on what kind of presentations will be effective and clear to diverse audiences, and how presentation of data fairly represents the issue, what the data mean in the context of the project, and project history. Are comparisons of responses by certain participant groups important to show? What are the priorities for data to show, for which audiences? These and other matters can be discussed and options reviewed, with the support of the Evaluation Committee as needed.

Monitor the Impact of the Initiative

Over and above the impact or outcomes of any planned and implemented intervention, community-academic partnered initiatives often have other kinds of impacts, such as building new capacities for community planning, or stimulating policy changes. For example, in the process of planning the Building Wellness pilot project of Witness for Wellness, discussions of the pilot design stimulated two organizations to develop a new partnership to share funding streams for care of mental illness. This represented a significant partnership development and a policy change. While one cannot always anticipate what kind of broader impact a program may have and when, it is important to put mechanisms in place to capture such impacts, by having check-points with agencies relating to the study, or doing occasional systematic phone calls or surveys to partners. This will help ensure that victories are recognized and celebrated.

Similarly, leadership development in working groups can be tracked through participant surveys or interviews, which can also provide information on views of what is or is not working in the partnership and satisfaction with the work that has been accomplished.

The strength-based or asset-based perspective of partnered research means that the feedback that is received can and should include the strengths as well as limitations of accomplishments. Partnerships in communities often underestimate their good work, and evaluation can carry a negative connotation, especially in underserved communities. It is important to look fairly at the data, but to include an assessment of assets and accomplishments as well as ongoing unmet needs and room for growth. It is important to celebrate the ability of the partnership to respond to this range as showing a true capacity for self-evaluation.

Leaders must diligently help groups to understand their good work and efforts, to lead to sustainable partnerships and the capacity for ongoing work, and, especially, to celebrate the victories.

Fig 7.11.

Share

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the board of directors of Healthy African American Families II; Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Reproductive Health; the Diabetes Working Groups; the Preterm Working Group; the University of California Los Angeles; the Voices of Building Bridges to Optimum Health; Witness 4 Wellness; and the World Kidney Day, Los Angeles Working Groups; and the staff of Healthy African American Families II and the RAND Corporation.

This work was supported by Award Number P30MH068639 and R01MH078853 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number 200-2006-M-18434 from the Centers for Disease Control, Award Number 2U01HD044245 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award Number P20MD000182 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Award Number P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control.

References

- R1.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: Preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl 1):S18–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R2.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R3.Israel BA, Farquhar SA, Schulz AJ, James SA, Parker EA. The relationship between social support, stress, and health among women on Detroit’s East Side. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):342–360. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]