Abstract

Long-term, prospective follow-up studies of children diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) show that symptoms tend to decline with age, but impairments in daily life functioning often persist into adulthood. We examined the developmental progression of impairments before and after the transition out of high school in relation to parent involvement during adolescence, parent support during adulthood, and college attendance, using 8 waves of data from the prospective 16-year follow-up of the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) Study. Participants were 548 proband children diagnosed with DSM-IV ADHD Combined Type and 258 age- and sex-matched comparison children (Local Normative Comparison Group; LNCG) randomly sampled from probands' schools. Impairment was assessed consistently by parent report from childhood through adulthood. Results showed that impairment worsens over time both before and after the transition to adulthood for those with ADHD histories, in contrast to non-ADHD peers, whose impairments remained stably low over time. However, impairment stabilized after leaving high school for young adults with ADHD histories who attended college. Involved parenting in adolescence was associated with less impairment overall. Attending college was associated with a stable post-high school trajectory of impairment regardless of parents' involvement during adolescence, but young adults with histories of involved parenting and who attended college were the least impaired overall.

Keywords: ADHD, impairment, trajectories, parenting, college

For many children diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), symptoms (particularly of the hyperactive/impulsive type) decline with age (Fischer, Barkley, Fletcher, & Smallish, 1993; Hart, Lahey, Loeber, Applegate, & Frick, 1995; Hinshaw et al., 2012; Molina et al., 2009), but impairments in daily life functioning typically persist into adulthood. In one sample of children with ADHD, just 20% met DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD symptoms by young adulthood, but over 60% had clinically significant impairment (Sibley, Pelham, Molina, Gnagy, Waxmonsky, et al., 2012a). Similar findings from another longitudinal sample showed that 35% of young adults continued to meet diagnostic criteria, but 72% were functionally impaired (Biederman, Petty, Evans, Small, & Faraone, 2010). Lower rates of diagnoses despite high rates of impairment may reflect the developmental insensitivity of DSM symptom criteria for ADHD in adolescence and adulthood (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2002) and the relative importance of impairment in daily life functioning (e.g., Fedele, Hartung, Cany, & Wilkowski, 2010). Impairments are thus essential to understanding how ADHD progresses into adolescence and adulthood. In the present study, we evaluate trajectories of impairment before and after the transition out of high school and consider parenting and college attendance as factors that may shape the developmental course of impairment through young adulthood.

Children with ADHD display impairments in family functioning, peer relationships, and academic functioning that only modestly correlate with symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity (Burns, Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, & Geiser, 2014; Gathje, Lewandowski, & Gordon, 2008; Gordon et al., 2006). In treatment studies, improvements in specific domains of functional impairment co-occur with symptom improvements for less than half of children (Karpenko, Owens, Evangelista, & Dodds, 2009; Owens, Johannes, & Karpenko, 2009). However, impairments are typically the basis for referral to treatment (Pelham & Fabiano, 2008) and are key targets of treatment (Chronis et al., 2001). As children age, impairments become increasingly relevant due to their cost, education and employment implications, and potential for health consequences (e.g., Barkley et al., 2006; Kleinman, Durkin, Melkonian, & Markosyan, 2009). In early adolescence, increased academic workloads and greater demands for independent and organized work probably account for increased ADHD-related difficulties in high school despite declining symptom levels (Kent, Pelham, Molina, & Sibley, 2011; Langberg et al., 2011). Also during adolescence, peer relationships become more important and complex. Adolescents with childhood diagnoses of ADHD continue to experience elevated peer rejection compared to adolescents without ADHD (Bagwell, Molina, Pelham, & Hoza, 2001).

In general, the transition to adulthood spans several years and creates risk for previously well-functioning adolescents as they struggle with demands imposed by new contexts (Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004b). The transition to adulthood is a phase of intensified vulnerability for adolescents with ADHD who leave behind familiar environments and institutional supports after finishing high school (Heiligenstein, Guenther, Levy, Savino, & Fulwiler, 1999). Increased expectations for autonomy and environments that lack structure may lead to worsening impairments. Indeed, young adults with ADHD histories have fewer close friends, poorer educational outcomes, and are more often fired from their jobs compared to young adults without childhood ADHD (Barkley et al., 2006). Their performance on executive function tasks assessing inhibitory control and working memory is poorer (Murphy et al., 2001), and their rates of internalizing, externalizing, and substance use disorders are higher (Biederman et al., 2006). Two factors that may be relevant to the developmental course of impairment after high school are the ongoing presence of involved and supportive parents and college attendance.

Parent involvement and support

Parents' relationships with their children resonate across the lifespan. Higher-quality parenting from childhood through the early twenties (e.g., greater warmth and closeness) predicts competent and adaptive social, academic, and behavioral functioning during the transition to adulthood and beyond (Masten et al., 2004). For children with ADHD, positive, authoritative parenting in early childhood protects against future conduct problems (Chronis et al. 2007). Authoritative parenting and parental warmth also predict greater peer acceptance and less rejection (Hinshaw, Zupan, Simmel, Nigg, & Melnick, 1997; Hurt, Hoza, & Pelham, 2007). In one school-based sample, greater parental warmth buffered the adverse effect of inattentive symptoms on school social impairment (Kawabata, Tseng, & Gau, 2011). Over time, children with ADHD whose mothers possessed stronger parenting skills showed less academic and behavioral impairment by high school (Latimer et al., 2003). Positive parenting has also been shown to buffer the effect of ADHD symptom severity on task perseverance (Thomassin & Suveg, 2012; but see also Schroeder & Kelley, 2008). However, the link between positive parenting and improved child functioning is weaker for children with more severe ADHD symptoms (Healey, Flory, Miller, & Halperin, 2011). More severe ADHD symptoms are associated with negative parenting (e.g., inconsistent discipline, conflict), which in turn predicts poorer social skills (Kaiser, McBurnett, & Pfiffner, 2011). Reductions in negative and ineffective parenting practices during treatment predicts improvements in social skills and disruptive behavior (Hinshaw et al., 2000).

Involved and supportive parents continue to reinforce positive outcomes as adolescents make the transition to adulthood (Masten et al., 2004). Warm, supportive, and involved parenting predicts greater school engagement through high school, and in turn more years of post-secondary education (Hill & Wang, 2014). For college students with ADHD, parent support is also associated with lower levels of depression (Meinzer, Hill, Pettit, & Nichols-Lopez, 2014). Young adults with supportive parents clearly experience more positive outcomes and are likely less impaired, but do they become less impaired over time as they transition out of high school, and do the benefits of supportive parenting differ for those who do and do not attend college? Parent support during the transition to adulthood (e.g., consultation on important decisions, guidance for complex problem-solving, and support in coping with significant stressors) may be associated with progressive improvements in impaired functioning over time, but to our knowledge this question has not yet been tested.

College attendance

Children with ADHD are less likely than their non-ADHD peers to enroll in college (Barkley et al., 2006; Kuriyan et al., 2012). Yet, increasing numbers of college students are presenting with ADHD, with an estimated 2–8% of students on campus self-reporting clinically significant symptoms (DuPaul, Weyandt, O'Dell, & Varejao, 2009). It is unlikely that these students are a uniformly high-performing group who overcame their ADHD-related deficits. Indeed, inattentive symptoms are associated with poorer GPAs at the end of students' first year of college (Frazier, Youngstrom, Glutting, & Watkins, 2007). Compared to non-ADHD peers, college students with ADHD have lower high school GPAs, earn lower GPAs in college, have more academic concerns, and withdraw from more courses, despite similar hours spent studying (Advokat, Lane, & Luo, 2011; Blase et al., 2009). College students with ADHD display more social skills deficits (Shaw-Zirt, Popali-Lehane, Chaplin, & Bergman, 2005) and aggressive behavior (Richards, Deffenbacher, & Rosen, 2002; Theriault & Holmberg, 2001). They are also less likely to complete their degrees than peers without ADHD (Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008; Wolf, 2001). Thus, studies of college students with ADHD clearly demonstrate impairment, but whether this impairment has continued, or worsened, from childhood is unclear. Prospective longitudinal study of impairment following adolescents beyond the transition out of high school is needed to directly answer this question. For college students with ADHD histories, poorer executive function and difficulties with delaying reward at a time when self-regulation is still maturing creates a “double deficit” (Fleming & McMahon, 2012), and research is needed to determine whether involved and supportive parenting can help ease this transition. To our knowledge, these questions have yet to be tested.

The current study

In the present study we asked four questions about the developmental progression of impairment in adolescents with ADHD histories (MTA probands), compared to peers without ADHD (Local Normative Comparison Group; LNCG), before and after the transition out of high school:

-

(1)

Do impairments tend to increase, decrease, or remain stable as adolescents leave high school? Leaving behind familiar environments and supports, we anticipate impairment will increase after high school.

-

(2)

Are parent involvement and support, before and after the transition out of high school, related to less impairment and stable or declining rates of change in impairment? For adolescents whose parents are involved in their daily activities, and who continue to provide support after high school, levels of impairment may be lower and impairments over time may be more stable. Alternatively, less-impaired adolescents may invite and reinforce parents' efforts at being involved in their daily lives (exemplifying a kind of selection bias).

-

(3)

Do trajectories of impairment after high school differ for adolescents who do and do not attend college? Adolescents who go on to college are probably already less impaired than their non-college attending peers, but college is challenging, with heavy academic demands and expectations for independence that may lead to worsening impairments after high school.

-

(4)

Do parent involvement and support influence impairment and changes in impairment differently for college-attending compared to other young adults? A foundation of involved parenting followed by continued support in adulthood are likely to be advantageous for students, given the challenges of the college context, but young adults in non-college settings face their own set of challenges after leaving high school and may also benefit from a history of involved parenting and continued supportive relationships with parents.

Method

Participants were the 579 children initially recruited into the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) Study when they were aged 7 to 9.9 (M=8.5, SD=.80) and diagnosed with DSM-IV ADHD Combined Type. At each of six sites, between 95 and 98 children were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: multicomponent behavioral treatment (Beh), systematic medication management (MedMgt), the combination of the behavioral and medication treatments (Comb), or referral to usual community care (CC). Children with comorbid diagnoses participated, and exclusion criteria were limited to conditions requiring study-incompatible treatments (e.g., psychosis, neuroleptic mediation), inability to participate (e.g., hospitalization, IQ below 80), cross-arm contamination (children in the same classroom or household), and family-related risks and threats to full participation (e.g., history of abuse, parent stimulant abuse, non-English-speaking primary caregiver). Recruitment strategy, detailed exclusion criteria, diagnostic procedures, treatment, and sample demographic characteristics appear in other reports (Arnold et al., 1997; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999; 2004).

Participant assessments took place at baseline prior to treatment randomization, at 3 months, 9 months, and the conclusion of the 14-month treatment phase, and again at 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 years after treatment randomization. A local normative comparison group (LNCG) of n = 289 children was recruited at the 2-year assessment, randomly sampled from the same schools and grades as MTA probands, matched for age and sex. LNCG children's entry and exclusion criteria were the same as for probands except they were not required to have ADHD. They were followed from the 2- through 16-year assessments. From the original sample, 95% of the MTA probands contributed one or more data points between the 2- and 16-year assessments, and were retained in our analyses. All LNCG participants contributed data, but 31 children who were diagnosed with ADHD at study entry were excluded from analyses. The final sample size was n=806 (n=548 MTA, n=258 LNCG).

For the present study, we drew on participant assessments from the 2-year (M age=10.4, Range=8.2 to 13.9) through 16-year (M age = 25.0, Range = 21.7 to 28.6) follow-up waves of assessment. Participant retention across waves was high. In the present sample, 39% of MTA probands had complete data across all waves (n=215/548), and 39% were missing data on three or fewer waves (n=212/548). The remaining 22% were missing data on half or more of the waves. Fifty-nine percent of LNCG had complete data across all waves (n=152/258), and 32% were missing data on three or fewer waves (n=83/258). The remaining 9% were missing data on half or more of the waves. Analyses for the current study accommodated missing data using multiple imputation. This strategy is appropriate when the pattern of missingness in the data is unrelated to the dependent variable after controlling for relevant measured variables (the missing at random or MAR mechanism; see Enders, 2010; Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Cases with complete and incomplete data did not differ on impairment after controlling for differences between MTA probands and LNCG (F=.04, p=.85). We also performed a series of comparisons between cases with complete versus incomplete data and found that MTA probands with complete data differed from probands with incomplete data on just 6 of 23 baseline variables (participants with incomplete data were more often male, minority, had lower parent income, younger mothers, and had poorer physical health). LNCG with complete data differed from LNCG with incomplete data on 5 of 22 baseline variables (participants with incomplete data were more often male, had lower parent income, younger mothers, and had families who were divorced and who received social assistance). Participants with complete data were no different from participants with incomplete data on the majority of baseline sociodemographic and adversity variables tested (e.g., age, parent job loss, child health, school absences and repeated grades). Thus, we are confident that our data meet criteria for missingness at random (i.e., point estimates and standard errors of parameters in our analyses are not likely biased by attrition). All analyses were based on 100 imputed data sets generated in SAS PROC MI. Data were imputed for all assessments simultaneously, and imputed values were informed by auxiliary variables that were not part of our analysis but that were likely to inform any pattern of missingness in impairment (e.g., mothers' ages).

Measures

Transition out of high school and trajectory coding strategy

The timing of each participant's transition out of high school was not directly recorded as part of the MTA assessments. For participants with complete data, we designated the first wave of assessment out of high school as the first wave at which they had completed 12th grade and reported earning a high school diploma or GED. For participants with incomplete data, we applied the above criteria and also verified the wave closest to the transition out of high school by using the number of months they reported being out of high school. The post-transition trajectory was coded 0 at the first wave out of high school, which corresponded to the 8-year assessment for 13% of participants, the 10-year assessment for 67% of participants, the 12-year assessment for 18% of participants, and the 14-year assessment for 2% of participants. Subsequent waves were coded by adding the number of years since the first wave out of high school (e.g., 2, 4, 6 for a participant whose first wave out of high school was at the 10-year assessment). The pre-transition trajectory was coded by subtracting the number of years prior to the first wave out of high school (e.g., −8, −7, −4, −2 for a participant whose first wave out of high school was at the 10-year assessment). Some participants had no evidence of high school completion based on the above indices because they did not complete MTA study assessments past adolescence; thus, they contributed impairment information only to the pre-transition trajectory. There were 63 participants who dropped out of school (n=56/548 MTA probands, 10.2%; n=7/258 LNCG, 2.7%). For these participants, the “first wave out of high school” was assigned to the wave at which they were between 18 and 19 years old. We also applied this coding strategy to 10 participants who contributed impairment ratings at the 2-year assessment only.

Impairment was assessed by parent report using two measures. For participants under age 18, parents completed the Columbia Impairment Rating Scale (CIS; Bird et al. 1993), administered at the 2-year through 10-year assessments. For participants aged 18 and older, parents completed the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006), administered at the 8-year through 16-year assessments. In childhood, ratings were obtained from the child's primary caregiver. In adulthood, ratings were obtained from the parent or guardian/collateral reporter with the closest parent-like relationship to the target participant. Mothers provided 88% of all child and 85% of all adult impairment ratings; fathers provided 7% of all child and 10% of all adult impairment ratings. The remaining 5% of ratings were provided by grandparents, stepparents, foster parents, and other family members (e.g., aunts, uncles).

Our goal was to combine responses from the CIS and IRS to create a longitudinal measure that tracked participants' general impairment from late childhood through young adulthood. Although several CIS items overlap with IRS items, both scales contain many unique items assessing age-specific functioning (e.g., behavior problems on the CIS; problems affecting work on the IRS). Thus it is not appropriate to treat IRS-rated impairment after age 18 as a continuation of CIS-rated impairment in childhood and adolescence (i.e., we cannot assume or test longitudinal measurement equivalence across these scales; see Horn & McArdle, 1992). We used a technique for pooled or integrative data analysis to create a longitudinal measure of impairment (see Hussong, Curran & Bauer, 2013; Curran et al., 2008), as follows:

Feasibility

We first examined the content of the CIS and IRS to determine whether the scales contained common items. Common items are identical or highly similar in content and function as anchors between disparate scales to link item responses to a common metric over all ages and waves of assessment (described in the item response theory literature as scale aligning and equating; see Holland & Dorans, 2006). We matched four IRS items to CIS counterparts with highly similar content. For example, the IRS item assessing problems in relationships with other people his/her own age corresponded to the CIS item assessing problems getting along with kids his/her own age. Other common items assessed relationships/getting along with parents and siblings, and academic difficulties. The remaining items were unique to each scale. These included CIS items about behavior problems, activities and fun, and getting along with non-parent adults, and IRS items about problems affecting work, self-esteem, romantic relationships, and overall impairment severity.

Selecting an item set

We reviewed and narrowed the pool of items across both scales to those that could be used to define a unidimensional impairment construct. Our final item set contained 12 items, four of which were common to both scales. We harmonized the response scales of the IRS and CIS to be logically equivalent (see Hussong et al., 2013): Responses on the CIS ranged from 0 (no problem) to 4 (a very bad problem) whereas responses on the IRS ranged from 0 (no problem) to 6 (extreme problem). Item endorsement at the most extreme categories of the IRS was sparse (across all IRS items, between 2.6% and 7.4% of responses were in category 5; between 1.4% and 4.9% of responses were in category 6), so we combined responses at this level with responses in category 4 to create a 5-point response scale for IRS items that corresponded to the 5-point scale used on the CIS.

Developing a measurement model

We developed a formal factor analytic measurement model for the purpose of generating factor scores of impairment that would share a common metric over all ages and waves of assessment (i.e., a commensurate measure; see Hussong et al., 2013). We tested our measurement model on a cross-sectional calibration sample of our data, created by retaining impairment items from a single, randomly-selected wave of assessment for each participant in the study. Our measurement model regressed common and unique items from the CIS and IRS on a single latent variable representing impairment. To improve the precision of our factor scores, we conditioned the impairment factor on participants' age, ADHD vs. LNCG group, and sex. Final parameter estimates from the conditional model were applied to a model using the full longitudinal sample. We extracted final factor scores from this model for use in our multilevel analyses. Scores ranged from −2.27 to 2.33 (M=−.43, SD=1.08).

Reliability, validity, and cross-validation

The average reliability of the impairment factor scores was r'=.86 (see Embretson & Reise, 2000, p. 18), and the test-retest correlation between scores at adjacent waves of assessment was r=.72. Correlations between impairment scores and other study measures, described below, were in expected directions (Table 1) and support the validity of the measure. We replicated our measurement model with a second, non-overlapping cross-validation sample of our data, created by retaining data from a single, randomly-selected wave of assessment for each participant from among the remaining waves not included in our calibration sample. Factor scores from the models based on the calibration and cross-validation samples were correlated above r=.99.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Study Variables

| MTA Probands | LNCG | Lower triangle = MTA probands; Upper triangle = LNCG | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| 1. Impairmenta | −.01 | .94 | −1.20 | .89 | 1 | −.14* | −.08* | −.06* | −.05* | - | −.05* | −.04 | −.07* | .05* | −.11* | −.02 | −.03 | .03 | .19* | .24* | .28* |

| 2. Parent involve (adol) | 3.58 | .46 | 3.78 | .47 | −.12* | 1 | .20* | .00 | .10* | - | .09* | −.03 | .06* | .08* | .03 | −.05* | .02 | .03 | −.02 | .00 | −.08* |

| 3. Parent support (adult) | 2.95 | .84 | 2.94 | .83 | −.06* | .15* | 1 | .01 | −.02 | - | .21* | .07* | .10* | .05* | .03 | −.01 | −.03 | .01 | −.06* | −.03 | −.08* |

| 4. Agea | 17.10 | 5.00 | 16.91 | 4.91 | .15* | .01 | −.00 | 1 | .02 | - | −.00 | .01 | −.02 | −.04* | −.07* | −.01 | .27* | −.04 | .01 | −.06* | .02 |

| 5. Family income | 4.93 | 2.49 | 5.86 | 2.61 | .03 | .06* | −.05* | .04 | 1 | - | −.06* | −.31* | −.24* | .13* | .37* | −.24* | .06 | −.07 | −.04 | −.08* | −.03 |

| 6. Special education | 279.23 | 398.72 | - | - | .13* | .06* | .03 | −.01 | −.05* | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Female (%) | 19.89 | - | 19.77 | - | −.03 | .07* | .11* | .03 | .08* | −.06* | 1 | −.01 | .03 | .04 | .12* | −.02 | .00 | .00 | −.07* | −.00 | −.05 |

| 8. Black (%) | 19.71 | - | 11.24 | - | .05* | .02 | .12* | −.03 | −.22* | −.01 | −.01 | 1 | −.13* | −.12* | −.10* | .16* | −.05 | .04 | .01 | .00 | −.00 |

| 9. Hispanic (%) | 6.93 | - | 13.18 | - | −.01 | −.13* | .02 | −.00 | −.16* | .01 | −.05* | −.13* | 1 | −.13* | −.17* | .10* | −.12* | −.00 | −.04 | .03 | −.03 |

| 10. Other (%) | 12.04 | - | 11.24 | - | .03 | .00 | .06* | −.03 | −.08* | −.01 | −.04* | −.17* | −.09* | 1 | .04 | −.06* | .02 | .01 | .04 | .02 | .06* |

| 11. Attended college (%) | 42.15 | - | 67.87 | - | −.07* | .15* | −.02 | .07* | .27* | −.17* | .11* | −.07* | −.07* | .02 | 1 | −.27* | .18* | −.14* | −.01 | −.03 | −.02 |

| 12. Dropped out (%) | 10.22 | - | 2.71 | - | .09* | −.14* | −.00 | .02 | −.17* | .01 | −.04* | −.04* | .05* | .00 | −.32* | 1 | −.06 | .06 | .00 | −.02 | .03 |

| 13. Living indepa (%) | 35.78 | - | 43.81 | - | −.09* | −.01 | −.06 | .20* | .09* | −.12* | .05 | −.04 | −.05 | −.03 | .05 | −.08* | 1 | −.11* | .08 | .09* | −.08 |

| 14. Other livinga (%) | 2.64 | - | 1.55 | - | .04 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .05 | −.01 | −.02 | −.01 | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | .05 | −.12* | 1 | −.01 | −.03 | −.02 |

| 15. ADHD dxa (%) | 37.80 | - | 2.00 | - | .30* | −.05* | −.04 | −.23* | −.01 | .05* | −.02 | .06* | .00 | −.01 | −.06* | .02 | −.08* | −.01 | 1 | .13* | .16* |

| 16. Internalizing dxa (%) | 18.85 | - | 7.83 | - | .11* | .02 | .01 | −.26* | −.05* | .01 | .07* | .04* | .01 | .02 | −.04* | .01 | .02 | .04 | .19* | 1 | .16* |

| 17. Externalizing dxa (%) | 31.37 | - | 4.58 | - | .31* | −.12* | −.02 | −.25* | −.04* | .06* | −.05* | .04 | .03 | .01 | −.08* | .08* | −.10* | −.02 | .30* | .26* | 1 |

Note. Impairment factor scores are on a conditionally standardized scale, with values ranging from −2.27 to 2.33. On average, impairment scores for MTA probands were 1.2 standard deviations higher than for LNCG. Parent involvement ranged from 1 to 5. A score of 3=sometimes and 4=often. Parent support ranged from 1 to 5. A score of 3=very much and 4=extremely much. Family income at baseline was reported on a 9-point scale. Each point represented an interval of $10,000 in annual income. A score of 4=$30,000 to $40,000 per year; a score of 5=$40,000 to $50,000 per year.

Impairment, age, living arrangements, and diagnoses (ADHD, internalizing, externalizing) varied from wave to wave. Summary statistics in this table pool over all waves of assessment.

p<.05

Parent involvement and support

Parent involvement was assessed in adolescence, and parent support was assessed in young adulthood. For participants under age 18, parents completed the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Frick, 1991) at the 2-year and 6- through 10-year assessments. The 10-item involvement subscale used in this study assessed parents' involvement with and conversations about their child's daily activities, homework, and friends, as well as parents' participation in school and extracurricular activities. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Scores across assessments on the involvement subscale were averaged to create a measure of mean parent involvement in adolescence.

Participants aged 18 and over completed the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 2009) at the 12-year through 16-year assessments. Subscales assessed young adults' reliance on their mothers/fathers for support with personal problems, advice, sympathy (support subscale; 3 items) and for help working through challenges and completing tasks (instrumental aid subscale; 3 items). These items were combined with a companionship item assessing social time spent with mothers and fathers to form a 7-item measure of parent support. Participants separately rated their mothers and fathers on a scale ranging from 1 (little or none) to 5 (most). Ratings of mothers and fathers were averaged to create a parent composite, and composite scores across assessments were averaged to create a measure of mean parent support in young adulthood. Participants tended to rate their parents similarly, and discrepancies between participants' perceptions of support from mothers and fathers were unrelated to impairment.

College attendance

Participants were contrast-coded as having attended college (−.5=did not attend; .5=attended college) if at any time from the first wave out of high school and through later waves they indicated current full-time enrollment in a college, university, community college, or post-college graduate program, or if they reported completing at least their first year of college/university/community college. Of the participants who contributed data on college attendance (n=752), 42.1% of MTA probands attended (n=212 of 503), compared to 67.9% of LNCG (n=169 of 249). Two-thirds of college-attending participants were enrolled at their first assessment out of high school, and an additional 26% were enrolled by their second assessment out of high school. Thus, the majority of participants who attended college were traditional-aged students who enrolled immediately or almost immediately after completing high school.

Covariates

Analyses modeled differences between participants with and without childhood ADHD histories (0=ADHD, 1=LNCG), biological sex (0=male, 1=female), ethnicity (three dummy-coded variables to assess differences between Black, Hispanic, and Other ethnicity compared to White), baseline family income (1= less than $10,000 to 9=$75,000 or more), participants' ages within each wave (assessments were not equally spaced for all participants and there was age variability at each wave), whether participants completed high school or dropped out (0=completed high school, 1=dropped out), and participants' post-transition living arrangements (two dummy-coded variables to assess living independently and other living arrangements compared to living in a family or non-family member's household). Ongoing ADHD diagnostic status and internalizing and externalizing comorbidity were also included as covariates, based on responses collected from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; parent and youth versions; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). ADHD diagnostic status was treated as a time-varying covariate: participants were coded at each wave of assessment based on whether they met criteria for an ADHD diagnosis of any subtype from parent- or self-report criteria. Internalizing and externalizing diagnoses at each wave were condensed into codes indicating whether a diagnosis was present at one or more assessments during the pre-transition phase (adolescence), during the post-transition phase (young adulthood), or during both phases. Participants had an internalizing diagnosis if they met criteria for major depression, dysthymia, mania, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Participants had an externalizing diagnosis if they met criteria for conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder. We used weighted effects coding in our analyses to model the effects of having each type of diagnosis during pre-transition, post-transition, or both phases (see Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003, pp. 328–332).

In a supplementary analysis of the MTA probands only, we also included as covariates original randomized treatment (contrast coded; see Jensen et al., 2007; Swanson et al., 2001) and use of special education services during school years (summing over all school years, total number of occasions participants received special education classes or programming, occupational/physical therapy, speech-language therapy, or participated in a special school for children with ADHD or LD).

Analytic Strategy

We tested a two-level multilevel growth model for impairment with SAS PROC MIXED. We used a piecewise linear function (Flora, 2008) to separately model rates of change in impairment through adolescence (Piece 1; the pre-transition trajectory) and after the transition out of high school (Piece 2; the post-transition trajectory). These trajectories and their interaction with ADHD vs. LNCG group tested our first question regarding rates of change before and after the transition out of high school for those with and without ADHD histories. Main effects of parenting and interactions between parenting measures and each of the pre- and post-transition trajectories tested our second question regarding the influence of parent involvement and support on severity and rates of change in impairment. The main effect of college attendance and the interaction with the post-transition trajectory tested our third question regarding the relation between college attendance and impairment after high school. Interactions between parenting and college attendance tested our fourth question regarding differential association of parenting with impairment in college- vs. non-college-attending young adults. ADHD vs. LNCG differences were examined for tests corresponding to each research question. We performed a second, supplementary multilevel analysis of impairment in MTA probands only, adding randomized treatment assignment and receipt of special education services as covariates.

Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables. Impairment scores, derived from the nonlinear factor analysis model, are on a conditionally standardized scale. A score of zero represents MTA probands' mean impairment at the first wave out of high school. In contrast, LNCG mean impairment was 1.2 standard deviations lower at the first wave out of high school (a score of −1.2). Mean levels of parent involvement in adolescence and parent support in young adulthood were similar for MTA probands and LNCG participants. However, 68% of the LNCG attended college full-time after high school compared to 42% of MTA probands; similarly, fewer than 3% of LNCG dropped out before completing high school compared to 10% of MTA probands. Mean family income at the baseline assessment was approximately $10,000 higher for LNCG families compared to MTA proband families; however, the LNCG baseline assessment occurred two years after MTA probands' baseline assessment. During waves of assessment after the transition out of high school, MTA probands reported living independently 36% of the time compared to 44% for LNCG. MTA probands also received on average 279 occasions of special education services over the course of their years in school (SD=398.72; Median=76; Range=0 to 2268).

Pearson correlations between study measures in Table 1 were similar for MTA probands and LNCG: Impairment was negatively correlated with parent involvement and support; parent involvement in adolescence was positively correlated with attending college; family income was positively correlated with attending college and negatively correlated with dropping out. An internalizing diagnosis was associated with more impairment, and an externalizing diagnosis was associated with more impairment and less parent involvement. There were also some differences between ADHD and LNCG: Impairment in MTA probands was negatively correlated with living independently whereas living arrangements were unrelated to impairment for LNCG. Attending college was positively associated with living independently (includes college housing) for LNCG, but unrelated to living arrangements for MTA probands. Dropping out of school was associated with more impairment in MTA probands but was unrelated to impairment for LNCG. For LCNG only, an ADHD or other externalizing diagnosis was also negatively correlated with parent support in young adulthood.

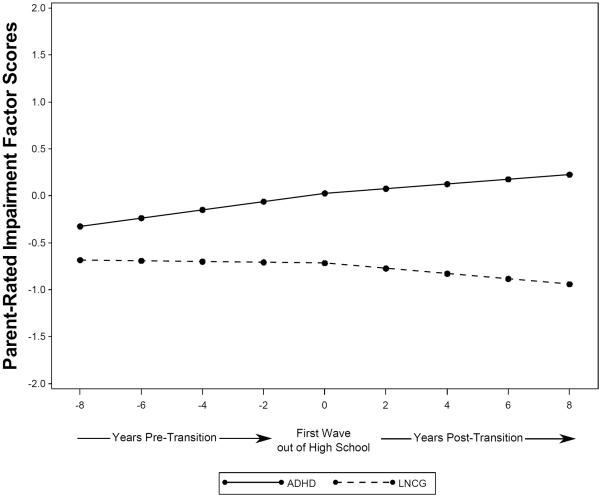

Table 2 and Figure 1 show results of the multilevel model of the developmental progression of impairment from adolescence through the transition out of high school and into young adulthood. For MTA probands, levels of impairment increased through high school (pre-transition trajectory B=.044, 95% CI = .034 to .054) and afterward, but at a slower rate (post-transition trajectory B=.025, 95% CI = .011 to .039). In contrast, impairment levels for LNCG participants were low and stable through high school (pre-transition trajectory B = .044 – .048 = −.004), and declined afterward (post-transition trajectory B = .026 – .053 = −.028). Following Barkley et al. (2002), we established a developmentally referenced criterion (DRC) for clinically significant impairment of +2 SD above the LNCG mean impairment score in each of the pre- and post-transition phases. Forty-two percent of MTA probands exceeded the pre-transition DRC at least once during adolescence, 52% exceeded the post-transition DRC at least once during young adulthood, and 27% exceeded both pre- and post-transition DRCs.

Table 2.

Multilevel Model Results Predicting Parent-Rated Impairment Before and After the Transition out of High School

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Intercepta | .026 | .037 |

| LNCG vs. ADHDb | −.743* | .062 |

| Pre-transition trajectory (Piece 1) | .044* | .005 |

| Post-transition trajectory (Piece 2) | .025* | .007 |

| LNCG differences in impairment trajectories | ||

| LNCG vs. ADHD × Piece 1 | −.048* | .007 |

| LNCG vs. ADHD × Piece 2 | −.053* | .013 |

| Mean parent involvement (adolescence) | −.130* | .058 |

| Mean parent support (young adulthood) | −.019 | .024 |

| College attendance post-transitionc | −.059 | .055 |

| Parenting and College differences in impairment trajectories | ||

| Parent involvement, adolescence × Piece 1 | .009 | .007 |

| Parent support, young adult × Piece 2 | .003 | .006 |

| College attendance × Piece 2 | −.032* | .011 |

| Effects of parenting for college-attending young adults | ||

| Parent involvement, adolescence × College | −.075 | .111 |

| Parent support, young adult × College | −.038 | .047 |

| LNCG differences in parenting and college effects | ||

| Parent involvement, adolescence × LNCG vs. ADHD | .088 | .091 |

| College attendance × LNCG vs. ADHD | −.014 | .088 |

| Parent involvement, adolescence × College × LNCG vs. ADHD | −.568* | .182 |

Represents average impairment at the first wave out of high school for MTA probands;

MTA probands = 0, LNCG = 1;

Contrast coded: Did not attend college = −.5, Attended college = .5;

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Model-implied trajectories of parent-rated impairment through the transition out of high school for MTA probands (ADHD) and non-ADHD age- and sex-matched peers (LNCG). A value of 0 on the x-axis represents for each person their first wave of assessment out of high school.

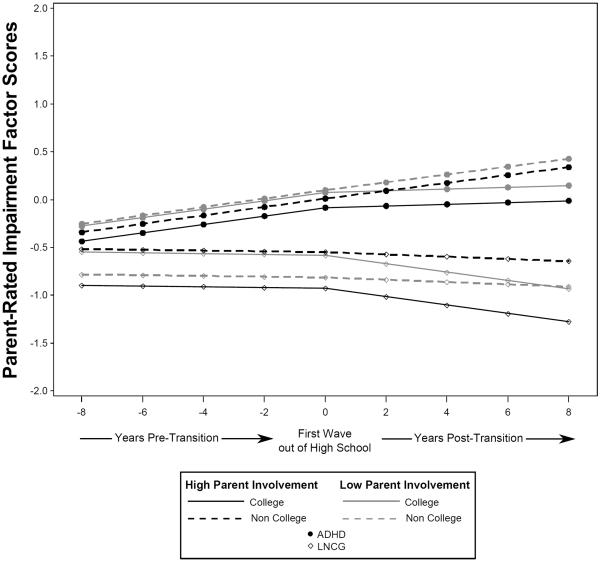

As shown in Table 2, parent involvement was associated with lower overall levels of impairment (B=−.130, 95% CI = −.243 to −.016), but parent support was not (B=−.019, 95% CI = −.060 to .028). There was no main effect of college attendance on impairment, indicating that people who went on to college after high school had similar levels of impairment at the first wave out of high school compared to non-college attending peers (B=−.059, p=.286). Figure 2 shows that college-attending young adults whose parents were more involved during adolescence showed the most dramatic improvements over time, and were the least impaired overall as shown by the solid black lines for both ADHD and LNCG. However, this finding was significant only for the LNCG (B=−.568, 95% CI = −.925 to −.212); it was weaker and non-significant for MTA probands (B=−.075, 95% CI = −.293 to .144).

Figure 2.

Model-implied trajectories of parent-rated impairment through the transition out of high school for college- versus non-college-attending young adults (ADHD and LNCG) with higher versus lower parent involvement (M +/− 1 SD) in adolescence.

For college-attending young adults with ADHD histories, impairment trajectories stabilized following the transition out of high school (B=−.032, 95% CI = −.053 to −.010; see also Figure 2). This stabilizing trend was unrelated to parents' level of involvement during adolescence or to parents' level of support during young adulthood1. Indeed, pre-transition impairment trajectories were virtually identical for college- and non-college bound adolescents with ADHD histories who had less-involved parents (grey lines in Figure 2), and only after leaving high school did impairments stabilize for those who attended college.

Covariates linked to greater impairment levels were higher baseline family income (B=.025, SE=.008), and older age within wave (B=.032, SE=.012). An ADHD diagnosis at a given assessment was also associated with greater impairment at that wave (B=.421, SE=.030). Adolescents who met criteria for an internalizing diagnosis at least once before, but not after, the transition out of high school were slightly more impaired (B=.092, SE=.026). Those who met criteria for an internalizing or externalizing diagnosis at least once before and after the transition out of high school were the most impaired, especially those with persistent externalizing comorbidity (B=.210, SE=.059 and B=.417, SE=.045 for internalizing and externalizing, respectively). Meeting criteria for an externalizing diagnosis after, but not before, the transition out of high school also predicted greater impairment (B=.209, SE=.081).

Sex, ethnicity, dropping out before completing high school, and post-transition living arrangements were unrelated to impairment. In a supplementary analysis of MTA probands only, original randomized treatment assignment did not contribute to impairment. A small effect of use of special education services in school (B=.00021, SE=.00006, p < .05), indicated that participants who received more occasions of special education services through the end of high school were more impaired at their first assessment out of high school. Assuming that services were delivered at a rate of once per day, one year's worth of special education services (181 days; U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2013) corresponded to impairment levels that were .038 units—about of a standard deviation—above average. Effects of other predictors and covariates corresponded to the findings from the full sample, except that age within wave was no longer associated with impairment, Black ethnicity was associated with greater impairment (B=.162, SE=.062), and internalizing and externalizing diagnoses were only associated with greater impairment if a diagnosis was present during both the pre- and post-transition phases.

Discussion

This study assessed the developmental progression of parent-rated impairment, for children with ADHD Combined Type histories compared to non-ADHD peers, from early adolescence through the transition out of high school and into young adulthood. We tested associations of parent involvement, support, and college attendance with changes in impairment before and after the transition out of high school, and whether parenting was differentially associated with change in impairment for young adults who did and did not attend college. There were three key findings: (1) On average, the impairments of adolescents with childhood ADHD increased through high school and after the transition out of high school whereas impairments in LNCG adolescents remained low over time and declined after high school; (2) the post-transition trajectory of impairment stabilized for adolescents with ADHD histories who attended college; and (3) involved parenting in adolescence was negatively associated with impairments overall, and especially for those who attended college. Overall, our findings reveal that ADHD-related impairments persist beyond the transition out of high school but are related to parenting and college attendance. Adolescents (with and without ADHD histories) who grew up with involved parents, attended college, and maintained supportive relationships with parents in young adulthood had the lowest levels of impairment overall and over time.

Impairments continue to increase after the transition out of high school

Previous studies show that children with ADHD continue to manifest impairments in a variety of domains through adolescence (Sibley et al., 2012b) and into young adulthood (Barkley et al., 2006), and that impairments in most domains remain problematic despite symptom reductions (O'Connor, Garner, Peugh, Simon, & Epstein, in press). This study is the first to articulate a progression of impairment over time, from early adolescence through young adulthood. On average, adolescents with ADHD histories became slightly more impaired through high school, and impairments continued to increase, but at a slower rate after the transition out of high school. In contrast, their non-ADHD peers maintained low levels of impairment through adolescence that declined further after the transition out of high school. Rates of clinically significant impairment based on developmentally referenced criteria are consistent with longitudinal trends, suggesting that impairments continue, and potentially worsen, for a substantial number of young people as they make the transition out of high school. These findings are concerning given the high personal and economic costs for young adults with ADHD and their families, such as failure to complete college and subsequent lower earning potential, and early pregnancy (Barkley et al., 2006; Flory, Molina, Pelham, Gnagy, & Smith, 2006).

However, not all adolescents with ADHD follow a worsening trajectory. Our finding of modest average increases over time summarizes a great deal of individual variability. Studies of symptom trajectories of children with ADHD show that about 25% to 30% exhibit a worsening pattern over time (Howard et al., 2015; Malone, Van Eck, Flory, & Lamis, 2010; Pingault et al., 2014; Swanson et al., 2007). In the present study, 27% of MTA probands persisted with clinically significant impairment before and after the transition out of high school, and impairments were most severe for the minority of adolescents with persistent externalizing comorbidity. Thus, while some adolescents with ADHD histories experience worsening impairments over time, others' impairments likely stabilize or become less severe. Our remaining research questions addressed whether college attendance and parent involvement and support were associated with such stability or improvement.

College students' impairment trajectory stabilizes after the transition out of high school

Impairments in college-attending young adults with ADHD histories stabilized after the transition out of high school. There were no differences in impairment at the first wave out of high school between college-bound adolescents and their non-college peers, suggesting that this stabilizing pattern was not exclusively a selection effect of less-impaired people going to college. Importantly, the trajectory of impairment for this group changed course at the first wave out of high school, suggesting that changes occurring around the time of college enrollment contributed to diminished impairment, independent of parent involvement and support. Despite greater impairment relative to non-ADHD peers, it is encouraging that impairments remained stable. The transition out of high school and into college can be an opportunity for struggling adolescents to disengage from the constraints and lack of flexibility typical of high school (Schulenberg, Bryant, & O'Malley, 2004a).

However, while college students with ADHD histories may show some success in managing their newfound independence, their impairments are not improving. Indeed, 47% of young adults with ADHD histories who attended college exceeded the post-transition DRC threshold for clinically significant impairment at least once in young adulthood. Poorer executive function and low self-regulation in a context where demands for cognitive skills are high places those with ADHD histories at a disadvantage (Dvorsky & Langberg, 2014; Fleming & McMahon, 2012). College is a unique developmental context in which students experience multiple, simultaneous transitions and assume new levels of independence. Students form new social groups and leave others behind; they often move away from home; they encounter a broader range of academic choices and opportunities, but also navigate a new set of demands to independently manage their academic careers. Some students with ADHD may thrive in an environment where they are free to select their own classes and set their own daily schedules. For others, however, college lacks the benefits of day-to-day involvement from parents and teachers who regularly check students' progress and remind them about deadlines (Eccles, 2004; Maggs, 1997). The concurrent freedoms and responsibilities of college life may be overwhelming in the absence of a guiding structure.

Parent involvement is linked to reduced impairments

Greater parent involvement was associated with less impairment in adolescence, regardless of ADHD history. Early involved parenting was associated with a reduction in overall impairment of about a third of a standard deviation for adolescents with ADHD histories compared to their peers whose parents were less involved. Less-impaired adolescents may invite and reinforce parents' efforts at involvement in their daily lives, but impairments only began to improve after the transition out of high school At this time, impairments slowed for college-bound adolescents with any level of parent involvement, and young adults with more involved parents and without ADHD histories showed the strongest improvements. Parent support during young adulthood was not significantly associated with reduced impairment, and effects of parent support were similar for those who did and did not attend college.

Involved parenting in adolescence may contribute more strongly to reduced impairment because it sets the stage for autonomy and self-regulation in young adulthood. For typically-developing school-age children and adolescents, support and encouragement from parents facilitates development of intrinsic control over behavior and motivation to achieve (Deci & Ryan, 2008). However, parent-control behaviors such as homework surveillance predict poorer classroom behavior and lower GPAs in school-age children, whereas autonomy-supportive parenting is correlated with achievement and higher GPAs (Ginsburg & Bronstein, 1993). Parent support after the transition out of high school, however, was not related to impairment in the present study. Our measure may have aggregated adaptive kinds of support such as advice, sympathy, and guidance to adult children to independently solve their own problems with maladaptive kinds of support such as hovering and intervening to solve problems on behalf of their children (see Cullaty, 2011). Overinvolvement from warm parents has only modest benefits for young adults, but overinvolvement paired with low warmth predicts lower self-worth and greater involvement in risk behaviors (Nelson, Padilla-Walker, & Nielson, in press).

Striking an appropriate balance of warmth, encouragement, control, and autonomy support may be especially challenging for parents of adolescents with ADHD histories, whose relationships are characterized by greater conflict compared to families of non-ADHD peers (Barkley et al., 1991; Walther et al., 2012). Preliminary results of a treatment program emphasizing parent-adolescent collaboration that increased parents' daily involvement in adolescents' academic routines had secondary benefits of improved parent-teen communication and increased autonomy-granting (Sibley et al., 2014). Adolescents who are raised in families that implement involved, authoritative parenting strategies may be better positioned to apply the self-regulation skills needed for success in college. Overall, levels of impairment in the present study were lowest for young adults with ADHD histories who attended college and who had more involved parents during adolescence.

Strengths and Limitations

We leveraged long-term follow-up data from a large, multi-site study of children well-diagnosed with ADHD Combined Type and an age-matched normative comparison group. An important strength of the MTA is that it was designed with broad generalizability in mind, with participants recruited from clinic and community settings (Arnold et al., 1997). However, children with ADHD inattentive subtype were not recruited into the study. Even though some shifted to this subtype with age (Molina et al., 2009), caution is warranted when generalizing the present findings to the broader population of children with ADHD. In the interest of generalizability, children were not excluded for comorbid diagnoses unless they required treatment in conflict with study treatment (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999).

A strength and a limitation of the present study was our parent-rated measure of impairment from late childhood through the late twenties. We constructed an integrated longitudinal measure of impairment from distinct adolescent and adult measures. This novel strategy allowed us to model long-term trajectories of impairment, but our measure combines information from two existing scales (the CIS and IRS), so our findings are not directly comparable to the adult impairment findings of others who used the IRS alone (Sibley et al., 2012a). Parents' reports of impairment in adulthood may also be less accurate for informants who don't live with their adult children and lack opportunities to directly observe their behavior. At the same time, young adults tend to under-report symptoms and impairment (Sibley et al., 2012a), and self-rated symptoms are poorer predictors of impairment in multiple domains compared to parent ratings (Barkley et al., 2002), so we believe that our findings based on parent ratings more closely resemble the true progression of impairment. However, parent informants were primarily mothers, mixed with father- and other-guardian informants, and there may be systematic differences between types of parent informants. A related concern is that we used parent-rated involvement during adolescence to predict parent-rated impairment. This raises the possibility of shared method variance: more involved parents may have a psychological investment in viewing their son or daughter as less impaired, justifying the time and energy spent on involvement.

Our impairment measure broadly assessed relational, academic, behavioral, and some emotional difficulties, and we cannot draw conclusions about how specific aspects of impairment change over time. A report in preparation will address more specific outcomes, such as college completion, current income, emotional lability, police contact, and pregnancy by age 18. With respect to college students with ADHD histories, it is concerning that students are less likely to complete their degrees compared to peers without ADHD, even when ADHD symptoms desist (Barkley et al., 2006). In the present study, we examined impairment trajectories of full-time students, but college attendance may not be associated with impairment in the same way for part-time students, who are typically less immersed and engaged in the academic and social contexts of college that are geared toward traditional-aged, full-time students (Nelson Laird & Cruce, 2009). Understanding the social and academic impairments in the college context for full- and part-time students with ADHD histories, and their impact on students' college completion, will be an important area for future study.

We examined the impairment trajectories of students who attended colleges/universities (four-year) and community colleges (two-year), but not of students who attended vocational, technical, or trade schools. High school academic problems, achievement test scores, and disciplinary sanctions differentiate students who enroll in four-year compared to two-year and vocational/technical colleges (Kuriyan et al., 2012), but no studies have yet examined differences in post-high school outcomes for students attending different types of post-secondary institutions, and none have compared student and non-student outcomes. This is an important avenue for further study considering that the majority of young adults with ADHD histories are not in school (Barkley et al., 2006).

Implications

Overall, results of this study suggest that adolescents with ADHD Combined Type histories and involved parents maintain lower levels of impairment as they move toward the transition out of high school. Regular conversations between parents and their children about daily activities and friends, help with homework, and parent participation in children's school and extracurricular activities are all important features of involved parenting that may help to reduce impairments well beyond the period of such active involvement. However, the developmental course of impairment stabilizes for young adults with ADHD histories who go on to college after high school, regardless of the extent of their parents' involvement during adolescence. A successful transition out of high school and into adulthood is an important developmental goal, and gaining admission to college is one early achievement of the transition to adulthood. Results of this study show that it coincides with a period of stability in impairments.

General Scientific Summary.

Adolescents with ADHD histories show increasingly impaired functioning as they age, but we found that the rate of change in impairments slowed after leaving high school. For adolescents who went on to college or university, impairments stabilized through young adulthood. Involved parenting in adolescence, combined with college attendance after high school, was associated with the lowest overall levels of impairment in those with and without ADHD histories.

Acknowledgements

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) was a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and finally under a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) contract. Collaborators from NIMH: Benedetto Vitiello, M.D. (Child & Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Interventions Research Branch), Joanne B. Severe, M.S. (Clinical Trials Operations and Biostatistics Unit, Division of Services and Intervention Research), Peter S. Jensen, M.D. (currently at REACH Institute and Mayo Clinic), L. Eugene Arnold, M.D., M.Ed. (currently at Ohio State University), Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D. (currently at Columbia); previous contributors from NIMH to the early phases: John Richters, Ph.D. (currently at National Institute of Nursing Research); Donald Vereen, M.D. (currently at NIDA). Principal investigators and co-investigators from the sites are: University of California, Berkeley/San Francisco: Stephen P. Hinshaw, Ph.D. (Berkeley), Glen R. Elliott, Ph.D., M.D. (San Francisco); Duke University Medical Center: Karen C. Wells, Ph.D., Jeffery N. Epstein, Ph.D. (currently at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center), Desiree W. Murray, Ph.D. (currently at Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute); previous Duke contributors to early phases: C. Keith Conners, Ph.D. (former PI); John March, M.D., M.P.H.; University of California, Irvine: James Swanson, Ph.D., Timothy Wigal, Ph.D.; previous contributor from UCLA to the early phases: Dennis P. Cantwell, M.D. (deceased); New York University: Howard B. Abikoff, Ph.D.; Montreal Children's Hospital/ McGill University: Lily Hechtman, M.D.; New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University/Mount Sinai Medical Center: Laurence L. Greenhill, M.D. (Columbia), Jeffrey H. Newcorn, M.D. (Mount Sinai School of Medicine). University of Pittsburgh: Brooke Molina, Ph.D., Betsy Hoza, Ph.D. (currently at University of Vermont), William E. Pelham, Ph.D. (PI for early phases, currently at Florida International University). Follow-up phase statistical collaborators: Robert D. Gibbons, Ph.D. (University of Illinois, Chicago); Sue Marcus, Ph.D. (Mt. Sinai College of Medicine); Kwan Hur, Ph.D. (University of Illinois, Chicago). Original study statistical and design consultant: Helena C. Kraemer, Ph.D. (Stanford University). Collaborator from the Office of Special Education Programs/US Department of Education: Thomas Hanley, Ed.D. Collaborator from Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention/Department of Justice: Karen Stern, Ph.D.

The work reported was supported by cooperative agreement grants and contracts from NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to the following: University of California–Berkeley: U01MH50461, N01MH12009, N01DA-8-5550; Duke University: U01MH50477, N01MH12012, N01DA-8-5554; University of California– Irvine: U01MH50440, N01MH12011, N01DA-8-5551; Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene (New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University): U01 MH50467, N01 MH12007, N01DA-8-5552; Long Island–Jewish Medical Center U01 MH50453; New York University: N01MH 12004, N01DA-8-5549; University of Pittsburgh: U01 MH50467, N01MH 12010, N01DA-8-5553; McGill University N01MH12008, N01DA-8-5548. The opinions and assertions contained in this report are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Disclosures: Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Lilly, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Shire, and YoungLiving (as well as NIH and Autism Speaks) and has consulted with or been on advisory boards for Arbor, Gowlings, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire, and Tris Pharma and received travel support from Noven.

Footnotes

Three-way interactions of parent involvement × college attendance × post-transition trajectory and parent support × college attendance × post-transition trajectory were not significant and trimmed from the final analyses.

References

- Advokat C, Lane SM, Luo C. College students with and without ADHD: Comparison of self-report of medication usage, study habits, and academic achievement. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2011;15(8):656–666. doi: 10.1177/1087054710371168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LE, Abikoff H, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott G, Greenhill LL, Wells KC. National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Multimodal Treatment Study of children with ADHD (the MTA) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:865–870. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Hoza B. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1285–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research cri- teria, III: Mother-child interactions, family conflicts, and maternal psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:233–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00304.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):279–289. http://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.111.2.279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in adults: What the science says. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Silva JM, Faraone SV. Young adult outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A controlled 10-year follow-up study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(2) doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, Small J, Faraone SV. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Research. 2010;177(3):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shaffer D, Fisher P, Gould MS, Staghezza B, Chen JY, et al. TheColumbia Impairment Scales (CIS): Pilot findings on a measure of global impairment for children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Blase SL, Gilbert AN, Anastopoulos AD, Costello EJ, Hoyle RH, Swartzwelder HS, Rabiner DL. Self-reported ADHD and adjustment in college: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;13(3):297–309. doi: 10.1177/1087054709334446. doi:10.1177/1087054709334446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Servera M, Bernad MDM, Carrillo JM, Geiser C. Ratings of ADHD symptoms and academic impairment by mothers, fathers, teachers, and aides: Construct validity within and across settings as well as occasions. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26(4):1247–1258. doi: 10.1037/pas0000008. http://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Fabiano GA, Gnagy EM, Wymbs BT, Burrows-MacLean L, Pelham WE., Jr. Comprehensive, sustained behavioral and pharmacological treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;8(4):346–359. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80008-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Williams SH, Baumann BL, Kipp H, Rathouz PJ. Maternal depression and early positive parenting predict future conduct problems in young children with Attenditon-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:70–82. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cullaty B. The role of parental involvement in the autonomy development of traditional-age college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2011;52(4):425–439. doi:10.1353/csd.2011.0048. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Cai L, Huang W, Chassin L, Sher KJ, Zucker RA. Pooling data from multiple longitudinal studies: The role of item response theory in integrative data analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):365–380. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.365. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life's domains. Canadian Psychology. 2008;49(1):14–23. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Weyandt LL, O'Dell SM, Varejao M. College students with ADHD: Current status and future directions. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;13(3):234–250. doi: 10.1177/1087054709340650. doi:10.1177/1087054709340650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky MR, Langberg JM. Predicting impairment in college students with ADHD: The role of executive functions. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1087054714548037. doi:10.1177/1087054714548037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Burrows-MacLean L. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the Impairment Rating Scale in samples of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(3):369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DA, Hartung CM, Canu WH, Wilkowski BM. Potential symptoms of ADHD for emerging adults. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32(3):385–396. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9173-x. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Fletcher KE, Smallish L. The stability of dimensions of behavior in ADHD and normal children over an 8-year followup. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21(3):315–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00917537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AP, McMahon RJ. Developmental context and treatment principles for ADHD among college students. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15(4):303–329. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0121-z. doi:10.1007/s10567-012-0121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB. Specifying piecewise latent trajectory models for longitudinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal. 2008;15(3):513–533. doi:10.1080/10705510802154349. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Jr., Gnagy EM, Smith B. Childhood ADHD predicts risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(4):571–577. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Glutting JJ, Watkins MW. ADHD and achievement: Meta-analysis of the child, adolescent, and adult literatures and a concomitant study with college students. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2007;40(1):49–65. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. Unpublished rating scale. University of Alabama; 1991. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral systems version. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33(5):470–478. doi: 10.1177/0165025409342634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathje RA, Lewandowski LJ, Gordon M. The role of impairment in the diagnosis of ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2008;11(5):529–537. doi: 10.1177/1087054707314028. http://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707314028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Bronstein P. Family factors related to children's intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Development. 1993;64(5):1461–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, Antshel K, Faraone S, Barkley R, Lewandowski L, Hudziak JJ, Cunningham C. Symptoms versus impairment: The case for respecting DSM-IV's Criterion D. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2006;9(3):465–475. doi: 10.1177/1087054705283881. doi:10.1177/1087054705283881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart EL, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Applegate B, Frick PJ. Developmental change in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in boys: A four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23(6):729–749. doi: 10.1007/BF01447474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey DM, Flory JD, Miller CJ, Halperin JM. Maternal positive parenting style is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Infant and Child Development. 2011;20(2):148–161. http://doi.org/10.1002/icd.682. [Google Scholar]

- Heiligenstein E, Guenther G, Levy A, Savino F, Fulwiler J. Psychological and academic functioning in college students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of American College Health. 1999;47(4):181–185. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Wang M-T. From middle school to college: Developing aspirations, promoting engagement, and indirect pathways from parenting to post high school enrollment. Developmental Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0038367. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0038367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Wells KC, Kraemer HC, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Wigal T. Family processes and treatment outcome in the MTA: Negative/ineffective parenting practices in relation to multimodal treatment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(6):555–568. doi: 10.1023/a:1005183115230. doi:10.1023/A:1005183115230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, Swanson EN. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):1041–1051. doi: 10.1037/a0029451. doi:10.1037/a0029451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Zupan BA, Simmel C, Nigg JT, Melnick S. Peer status in boys with and without Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Predictions from overt and covert antisocial behavior, social isolation, and authoritative Parenting beliefs. Child Development. 1997;68(5):880–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Dorans NJ. Linking and equating. In: Brennan RL, editor. Educational Measurement. 4th Ed Am. Counc. Educ./Praeger; Westport, CT: 2006. pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, McArdle JJ. A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Experimental Aging Research. 1992;18(3–4):117–144. doi: 10.1080/03610739208253916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Molina BSG, Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP, Belendiuk KA, Harty SC, Wigal T. Developmental progression to early adult binge drinking and marijuana use from worsening versus stable trajectories of adolescent attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delinquency. Addiction. 2015;110(5):784–795. doi: 10.1111/add.12880. doi:10.1111/add.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt EA, Hoza B, Pelham WE., Jr. Parenting, family loneliness, and peer functioning in boys with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(4):543–555. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9111-x. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Integrative data analysis in clinical psychology research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9(1):61–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185522. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Arnold L, Swanson J, Vitiello B, Abikoff H, Greenhill L, Hur K. 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):989–1002. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3180686d48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser NM, McBurnett K, Pfiffner LJ. Child ADHD severity and positive and negative parenting as predictors of child social functioning: Evaluation of three theoretical models. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2011;15(3):193–203. doi: 10.1177/1087054709356171. doi:10.1177/1087054709356171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpenko V, Owens JS, Evangelista NM, Dodds C. Clinically significant symptom change in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Does it correspond with reliable improvement in functioning? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(1):76–93. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20549. doi:10.1002/jclp.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Tseng W-L, Gau SS-F. Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and social and school adjustment: The moderating roles of age and parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;40(2):177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9556-9. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent KM, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Sibley MH. The academic experience of male high school students with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:451–462. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman NL, Durkin M, Melkonian A, Markosyan K. Incremental employee health benefit costs, absence days, and turnover among employees with ADHD and among employees with children with ADHD. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(11):1247–1255. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181bca68c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]