Abstract

Nurses are increasingly the primary contact for clients concerned about health problems related to their environment. In response to the need for nursing expertise in the field of environmental health, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), and National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) have designed core competencies for the nursing profession. The IOM competencies focus on four areas: (1) knowledge and concepts; (2) assessment and referral; advocacy, ethics, and risk communication; and (4) legislation and regulation. The competencies establish a baseline of knowledge and awareness in order for nurses to prevent and minimize health problems associated with exposure to environmental agents. To address the known difficulties of incorporating new priorities into established practice, nurses attending an environmental health short course participated in a nominal group process focusing on the question, “What specific actions can we take to bring environmental health into the mainstream of nursing practice?” This exercise was designed to bring the concepts of the national initiatives (IOM, NINR, ATSDR) to the awareness of individual nurses involved in the direct delivery of care. Results include 38 action items nurses identified as improving awareness and utilization of environmental health principles. The top five ideas were: (1) get environmental health listed as a requirement or competency in undergraduate nursing education; (2) improve working relationships with interdepartmental persons—a team approach; (3) strategically place students in essential organizations such as NIOSH, ATSDR, or CDC; (4) educate nurse educators; and (5) create environmental health awards in nursing. The 38 original ideas were also reorganized into a five-tiered conceptual model. The concepts of this model include: (1) developing partnerships; (2) strengthening publications; (3) enhancing continuing education; (4) updating nursing practice; and (5) strengthening schools of nursing. The model serves as a road map for action in building environmental health capacity within mainstream nursing.

Keywords: environmental health, nominal group process, thinking upstream, continuing education, curriculum revision, scope of practice, public health, nursing practice

Nurses have restored health through environmental interventions since the time of Florence Nightingale and her emphasis on light, fresh air, and cleanliness in the care of clients. As the delivery of health care changed over the past century, nurses' involvement in reducing environmentally induced health problems diminished. However, current findings regarding environmental etiologies of disease require nurses to recapture their expertise in environmental health principles.

Several national initiatives have been launched over the past 5 years to reestablish nursing capacity in environmental health. These efforts have been spearheaded by three organizations: the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ASTDR), and a multidisciplinary panel brought together by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). Nurses in these organizations have, for the first time, specified nursing competencies in environmental health. These competencies provide direction for the profession in the areas of environmental health assessment, referral, risk communication, and legislative issues.

Although the IOM, ATSDR, and NINR initiatives provide coherent goals for nursing, the challenges of implementation remain. Among the challenges are smaller operating budgets at hospitals and universities, universities facing already full curricula, individual nurses adopting changes in their practice techniques, the current nursing shortage, and finally, a lack of awareness of environmental health principles among nurses. Attendees of a recent conference on environmental health and nursing discussed the mandate to change their own practice and that of the profession as a whole to better reflect environmental health science. Through a nominal group process exercise, participants identified 38 action items to integrate the IOM, NINR, and ATSDR competencies into professional nursing practice.

Background of National Initiatives

Each national initiative provides direction for the profession by specifying activities (e.g., taking a health history), exposures (e.g., arsenic, lead), conditions (e.g., asthma), or policies (e.g., risk assessment) that nurses need to understand on behalf of the clients they serve. During the conference each of these initiatives was reviewed to provide the foundational underpinnings for the group's thinking.

Initiative 1: Institute of Medicine

The IOM is a non-government organization composed of experts in the health related fields who volunteer to advance and disseminate scientific knowledge to improve human health. “The Institute provides objective, timely, authoritative information and advice concerning health and science policy to government, the corporate sector, the professions and the public” (available: http://www.iom/edu/iom/). The IOM report titled Nursing, Health and the Environment (Pope, Snyder, & Mood, 1995) sets forth specific competencies for nursing practice, education, and research. Four general competency areas are proposed for all of the nation's 2.6 million nurses. These include:

Basic knowledge and concepts. Understanding scientific principles addressing individuals or populations and the environment. Explaining basic mechanisms of exposure to environmental health hazards, prevention and control strategies, the role of basic and applied research, and the interdisciplinary nature of environmental health.

Assessment and referral. Completing a comprehensive environmental exposure history and making appropriate referrals for conditions with probable environmental etiologies. Locating and providing appropriate scientific information for individual patients and communities.

Advocacy, ethics, and risk communication. Understanding the role of advocacy, principles of environmental justice, and risk communication in addressing environmental health issues.

Legislation and regulation. Understanding major areas of environmental health policy as well as state and national regulations addressing environmental health (Pope et al., 1995).

Initiative 2: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

ATSDR is the principal federal public health agency involved with hazardous waste issues. The Superfund Law created the agency in 1980. Its mandate is to help prevent or reduce the harmful effects of exposure to hazardous substances (e.g., chemical spills, waste disposal sites) on human health. ATSDR cooperates with state and local public health agencies to conduct medical assessments and promote communication and advocacy for affected citizens. ATSDR created the Environmental Health Nursing Initiative in 1994, recognizing the power of the nation's 2.6 million nurses in developing a national, integrated environmental health strategy. The goal of the initiative is to identify gaps in research, develop collaborative relationships with other agencies concerned with environmental hazards, and increase the presence of environmental health education opportunities to students and practicing nurses (available: http://www.ats-dr.cdc.gov/EHN/).

Initiative 3: National Institute of Nursing Research

The NINR initiative emphasizes the role of nursing research in correlating environmental agents and health consequences. It focuses on three areas: first, reducing hazards for high-risk population groups (e.g., migrant farm workers, older adults, and women of childbearing age); second, identifying target research areas and assessing for hazards (e.g., homes and workplaces); and third, determining infrastructure needs for enhancing the ability of nurses to investigate environmental health related issues. This involves identifying gaps in existing science and facilitating nursing research in that area (Grady, Harden, Moritz, & Amende, 1997).

Developing Strategies for Implementation

The final session of a 5-day environmental health course was used to develop strategies for incorporating environmental health competencies into nursing practice. The class was part of a conference titled, “Moving Upstream: Environmental Health and Nursing,” held in July 2000 at the College of Nursing at Montana State University—Bozeman. The course sessions focused on health effects secondary to environmental etiologies such as pesticide exposure, chemical and biologic contaminants in drinking water, and groundwater contamination from industrial solvents. Other topics included risk communication, advocating for change, and conducting an environmental health assessment. The objectives for each session were designed to reflect the intent of the four competencies set forth by the IOM. Case studies were used in many sessions to make more explicit the relationships between environmental agents and subsequent health problems. For example, a case study of an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund site addressed the health consequences (e.g., cancer, dermatitis, neurological changes) of rail yard contamination from diesel, perchloroethylene, and other volatile organic compounds. The class was offered to nurses from all specialty areas, although public health nurses constituted the majority of attendees. Attendees included nurse clinicians, academics, and researchers from Montana, California, Florida, Texas, and Connecticut.

The final conference session titled, “Charting our Future: A Group Process Activity Addressing the Future of Environmental Health and Nursing” was planned as an opportunity for course attendees to synthesize course information and provide suggestions about how to move environmental health into mainstream nursing practice.

Conducting a Nominal Group Process Exercise

Nominal group process (NGP) was chosen as the method of soliciting and organizing input from attendees; a step-by step overview of this process is provided in Table 1. NGP is a common technique that has been used to gather and distill group input on a variety of nursing topics, including staff concerns, clinical supervision skills, and program design (Cawthorpe & Harris, 1999; Sloan, 1999; Sarvela, Holcomb, & Odulana, 1992). In addition, nominal group techniques have been used to solicit faculty input in the revision of both nursing and medical curricula (Davis, Rhodes, & Baker, 1998; Moon, 1999; Lloyd-Jones, Fowell, & Bligh, 1999).

Table 1. Nominal Group Process Step by Step.

| Step | Group Facilitator Activities | Group Member Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Prior to group activity | Identify and clearly define the nature and scope of the problem to be discussed. | Inform group members on day 1 of conference that on day 5 the group process will occur. |

| Obtain poster board, tape, and felt-tipped pen. Prepare a “nominal group task statement” and make it available to each participant. | Request that group members write their solutions to the problem statement on the poster board. | |

| Introducing NGP to the group | Explain that the objective of the group activity on day 5 is to increase their understanding of the priorities of the movement. Explain that NGP will be the method of exploring problems. | |

| Relate time frame of 2 hr. | ||

| Subdivide large groups into subgroups of 7–10 and provide a working place, recorder, and facilitator for each subgroup. (The “Moving Upstream” group had 13 members) | ||

| Silent generation of ideas in writing | Instruct members to spend time throughout the following 5 days listing their suggested solutions to the problem. | Each group member lists solutions on a note pad and adheres the note pages to the poster board at the front of the room. |

| Encourage multiple entries. | Group members work independently. | |

| Instruct group members to save their discussion of the problem statement for the group activity on day 5. | ||

| Facilitated listing of ideas | Appoint two group members to number and write each idea on the white board at the front of the room. | Members may add additional items to the poster board while the listing process takes place if hearing the ideas of others inspires them. This is called “hitchhiking.” |

| Ideas are recorded as close to verbatim as possible. | ||

| Instruct the transcribers to leave a box to the left of each item where numeric rankings can be written later. (Consider having a staff member collect the pieces of notepaper to confirm that all ideas are represented on the white board. This person may then enter the ideas into a laptop and track the scoring electronically as well.) | ||

| Discussion of ideas on white board during transcription process | Position the white boards so that all participants can see all the distinct ideas. | Group members participate in rendering solutions as distinct or duplicate. |

| Facilitate a discussion during the transcription process to clarify the meaning of similar sounding solutions and distinguish their differences. | ||

| Similar solutions that are confirmed by the group members to be duplicates in meaning are identified and written as one solution. (In this case 45 ideas were reduced to 38 distinct solutions) | ||

| Rank ordering ideas | Advise participants to contemplate the solutions for 10 min to determine the five solutions they individually consider to be the most critical. | Group members ponder the ideas individually. |

| Ask each of the group members to list the five most critical solutions from the list. Members should assign a “5” to the item they perceive as most critical to the problem “4” to the next most critical, and so on. | Group members may take notes on the items they consider to be finalists. This will expedite the process of recording their numeric scores on the white board. | |

| Suggest that group members keep notes as they narrow the field to five to facilitate the scoring process. | Group members take turns recording their scores on the white board. | |

| Provide dry erase markers and instruct 2–3 participants at a time to record their numeric ranking in the margins next to the solutions, as they are ready. | ||

| Total rankings | Before the totals are summed, the facilitator double-checks with the group members to be certain they recorded their votes with the number 1 appointed to their fifth choice. | Group members confirm that they recorded their scores in the correct order. |

| After confirming that participants scored the ideas correctly, the facilitator and another group member each total the points for each item. Two people do this to ensure accuracy. | ||

| Discussion | After the ideas are ordered, group members are instructed to discuss the new list and then clarify and re-rank any of the items. | Group members may wish to change or re-rank the items and re-tally the final score. |

| Conclusion | The process ends when there is group consensus on critical items and their rank ordering. The group may choose at this time to move into a discussion of solutions based on the analysis of the problem. The facilitator thanks the group members for their attention and contributions. | Group members observe trends in the data. |

Van de Ven & Delbelq (1972) state that nominal group process is to be “problem centered.” The primary problem as identified by the IOM is the need to expand existing environmental health competencies in public, community, and occupational health nursing practice into mainstream nursing practice (Pope et al., 1995). Accordingly, the problem statement, “What specific actions can we do to bring environmental health into the mainstream of nursing practice?” was posed for the classroom exercise.

The problem statement was placed on a poster board at the front of the classroom on the first day of the 5-day conference. During course orientation, participants were oriented to the exercise and encouraged to record all of their proposed solutions on the poster board at any time throughout the conference. They were encouraged to work independently without group discussion on the problem statement to increase the number and variety of ideas individuals generated.

The course instructor facilitated the NGP. The 45 proposed solutions were analyzed for duplication, and 38 unique solutions (Table 2) were transferred onto a large white board where participants could read and ponder them. Participants were instructed to individually rank the five best ideas from the list. Participants registered their votes on the board, and scores were totaled and recorded.

Table 2. Activities Identified by Group Members to Bring Environmental Health Issues into the Mainstream of Nursing Practice.

| 1 | Environmental questions on recertification exams |

| 2 | NCLEX-RN questions on environmental health |

| 3 | Articles in American Journal of Nursing (AJN), Excellence in Clinical Practice, and Nurse Week on environmental health |

| 4 | Environmental health workshops |

| 5 | QA/TQM/CQI program with environmental health items |

| 6 | Strategically place students in essential organizations: NIOSH, ATSDR, CDC |

| 7 | Continuing education program in AJN on nursing and the environment |

| 8 | More basic information for nurses to demystify environmental health nursing |

| 9 | Improve working relationships with interdepartmental persons—a team approach |

| 10 | Adequate funding for education, planning, and implementation |

| 11 | Internet- or televideo-based programs (distance education) for nominal fees |

| 12 | A textbook for beginning environmental health nursing |

| 13 | Get environmental health listed as a requirement or competency in undergraduate nursing education |

| 14 | Education and classes for family nurse practitioners and doctors |

| 15 | Provide knowledge of environmental health to guidance counselors in high school setting to promote interest in this field |

| 16 | Incorporate environmental epidemiology into undergraduate and graduate curricula |

| 17 | Promote and recognize nurses working with the environment (i.e., create a registry of environmental health nurses (potential speakers) |

| 18 | Create a registry of potential employers of environmental health nurses |

| 19 | Educate nurse educators |

| 20 | Prepare/present environmental panels and programs at national meetings like APHA, ANA |

| 21 | Environmental health continuing education for all health care providers in all facilities |

| 22 | Public health nursing training, which is being developed, should include environmental health nursing |

| 23 | Training for the board of health and county commissioners |

| 24 | Recognize, identify and incorporate environmental health issues into our daily practice (lead by example and inform others that this is how we practice!) |

| 25 | Enlist the support of respected lobbying groups (e.g., Ralph Nader, AARP) to counter corporate groups |

| 26 | Environmental health nurse practitioner specialty |

| 27 | More environmental health in graduate education, not mixed with NP programs |

| 28 | Family/home assessment with an environmental health risk checklist |

| 29 | Broaden ownership of environmental health by articulating how the role is within scope of practice and how the role is different from other disciplines roles (i.e., public health/community health nursing) |

| 30 | Incorporate questions regarding environmental health into the admission history and assessment. |

| 31 | Network with our colleagues to see what is happening and what they are doing or seeing |

| 32 | Publicize environmental health nursing research agenda |

| 33 | Environmental health awards in nursing |

| 34 | Media campaign regarding environmental health nursing |

| 35 | Cultivate media friendships |

| 36 | Connect and explicitly state the relationships between environment and health (i.e., environment and prenatal risks, environment and poison control, environment and dermatological problems, environment and communicable disease) |

| 37 | Education departments of hospitals/county health department could have inservices on environmental causes of presenting illness and interventions to deal with it |

| 38 | Publish, publish, and publish |

The identification of the top five ideas reflects the group's perceptions of the most critical activities for moving environmental health into the mainstream of nursing practice. The top five ideas were: (1) get environmental health listed as a requirement or competency in undergraduate nursing education (item 13); (2) improve working relationships with interdepartmental persons—a team approach (item 9); (3) strategically place students in essential organizations such as NIOSH, ATSDR, or CDC (item 6); (4) educate nurse educators (item 19); and (5) create environmental health awards in nursing (item 33).

Analysis of Nominal Group Process Exercise

The highest ranked item (item 13) was to develop an across-the-curriculum approach to integrating environmental health into undergraduate nursing programs. Most participants did not consider it desirable to create a nursing subspecialty in environmental health (i.e., environmental health nurses). Rather, the suggested approach would integrate environmental health theory into the current undergraduate curricula. For example, case studies of environmentally induced illness in pediatric and adult clients could be added to the traditional case study profiles in maternity, pediatrics, and medical-surgical courses (i.e., IOM competency I). The nursing assessment course could incorporate questions regarding workplace exposures into the existing health history format (i.e., IOM competency II). Issues related to advocacy, ethics, and risk communication could be discussed in the legal and ethical concepts course (i.e., IOM competency III). The content regarding policy framework and environmental health regulations could be included in either the community health or management courses (i.e., IOM competency IV).

The item ranked second (item 9) focused on improving teamwork among groups of professionals. Environmental health is multidisciplinary by nature, because no single professional can hold all the expertise to address every facet of an environmental health problem. For example, in the case of a train derailment that released chlorine gas into the environment, many professionals would be involved in providing emergency response and acute care for exposed persons. An entire team of emergency response personnel, scientists, medical professionals, businessmen, remediation teams, and legal professionals would likely be collaborating to address different aspects of the same problem. Nurses need to know how to communicate clinical and toxicologic information to different professions during the acute event as well as in the weeks and months that follow such an incident. Moreover, nurses need to be able to communicate across professional boundaries in order to perform in their roles as client advocate and risk communicator. Some nurses identified authority-related boundaries within their current workplace hierarchy as an obstacle to the presence of nursing in multidisciplinary situations. Both nurses and administrators can improve teams by emphasizing collaboration, discarding previous authority related boundaries and adopting ability related role descriptions (B. J. Safriet, personal communication, October 5, 2000). Nurses may create a “seat at the table” for the profession by clarifying their goals during annual performance evaluations, contract negotiations/collective bargaining sessions, and by recruiting individuals into the profession who already have skills in other disciplines. Over time, the nurse gains authority and strengthens the image of the profession. This evolution enhances their ability to incorporate current science into health care organizations (i.e., IOM competency I) to be an advocate for clients (i.e., IOM competency III) and to communicate risk effectively (i.e., IOM competency III).

The third ranked activity (item 6) was to strategically place students in essential organizations such as NIOSH, ATSDR, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as part of their clinical experiences. While interning in federal, state, or community agencies, the students would build an awareness of current environmental health–related resources (i.e., IOM competency I) and the efficacy of other nursing professionals in reaching the public regarding environmental health issues (i.e., IOM competencies III and IV). Additionally, the presence of nursing students participating in clinical training in these agencies reinforces the legitimacy of nurses in policymaking positions.

The fourth ranked activity (item 19) was to educate nurse educators. This solution also emphasizes the importance of building environmental health into the foundations of professional nursing practice. Course attendants emphasized the need to call the attention of nurse educators to the role the environment plays in the manifestation of illness. One method for reaching nurse educators is to encourage attendance at continuing education sessions on subjects such as principles of risk communication, environmental epidemiology, and research methods. Other critical topic areas for nurse educators include environmental risks to childrens' health, minimizing exposure risks for immunosuppressed populations, and building awareness regarding industrial and vocational sources of exposure. An evaluation tool would be to form a national network of college of nursing deans and monitor the progress of their universities toward incorporating the IOM competencies into the curriculum. Educating the nurse educators is a broad intervention and has applications in all four of the IOM competency areas.

The fifth activity (item 33) involved providing a venue through which to honor and recognize professional nurses for including environmental health principles in their practice or research. Monetary rewards sponsored by environmental health agencies to support the recipient's attendance at continuing education events would be one way to encourage nurses to embrace the first IOM competency.

Observations of the Nominal Group Process

Nominal group process has the benefits of being democratic, highly structured, and relatively quick (Carney, McIntosh & Worth, 1996). Drawbacks to the technique include individual interpretations of the problem statement and the difficulty of differentiating between similar but not identical solutions. For instance, one idea was to “publish, publish, publish!” and another was to “publish articles in American Journal of Nursing (AJN), Excellence in Clinical Practice, and Nurse Week on environmental health.” While these ideas seem to represent a single notion to gain visibility, the individuals who generated the ideas had different intentions. The first was to publish prolifically and become very visible (e.g., Good Housekeeping, Parents), while the second participant thought peer-reviewed publications were a better idea. An additional drawback to NGP in this setting is a tendency to generate ideas that are a “mile wide and an inch deep.” This results in a global solution set for altering the profession that does not easily apply to changes in daily practice that nurses can make. Like the IOM competencies, some of the global solutions developed by the group will face difficulties in implementation.

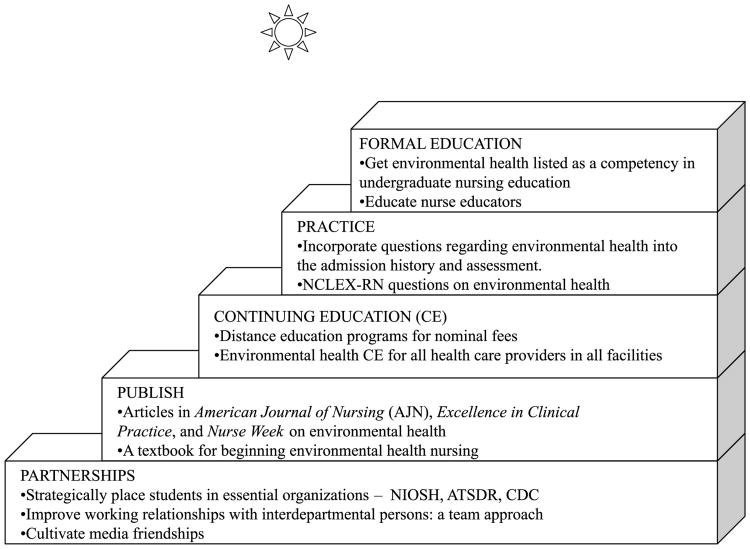

At the conclusion of the NGP, one participant spontaneously observed that the 38 original solutions were of two categories: conceptual and practical. Further discussion and observation revealed that the conceptual solutions fit into five categories and the practical solutions were steps for making progress toward those conceptual solutions. It is important to note that these five new categories differed in approach from the top five ideas identified in the previous part of the group discussion. Overall, these categories provided the basis for a conceptual model of environmental health action. The group illustrated the conceptual goals (Fig. 1) as an ascending staircase and assigned the corresponding action items to each step. This reorganization of the 38 solutions is likely due to the frequent use of the nursing process by the course participants. In the nursing process, long-term goals (i.e., the IOM competencies) are supplemented with short-term goals (i.e., the steps of the ascending staircase), and both are achieved through specific interventions (i.e., the action items assigned to each step). Although not intended to be part of the nominal group process, the five-tiered conceptual model did help achieve the overall objective of the course—to provide attendees with an opportunity to translate course information into an action plan.

Figure 1.

Concepts and action steps to move environmental health into the mainstream of nursing.

Conclusion

Since the time of Florence Nightingale, communities have looked to nurses to provide leadership in environmental health. Changes in technology and health care financing over the past few decades have de-emphasized the environmental health role of the nurse (Butterfield, 2000). However, current issues of air quality, water quality, and pesticide use, coupled with new findings about asbestos and “sick” buildings, have once again created an atmosphere in which people are looking to nurses for answers. Nurses must be able to respond to clients' questions and concerns about the environments in which they live, work, and play. Nurses must develop a capacity to respond to environmental health issues in the communities where they practice or teach.

The IOM, NINR, and ATSDR competencies provide a foundation that will accelerate growth and change within our profession. The task of incorporating those competencies into mainstream nursing practice is challenging for public health departments facing smaller budgets, universities facing already full curricula, and individual nurses facing new practice techniques. Participants in an environmental health and nursing course agreed that progress toward proficiency in the IOM competencies will have to come in the form of incremental efforts to increase awareness among practicing nurses and to encourage universities to augment their programs with the fundamentals of environmental health. Participants determined that the five most critical steps to achieving the IOM competencies are to: (1) get environmental health listed as a requirement or competency in undergraduate nursing education; (2) improve working relationships with interdepartmental persons—a team approach; (3) strategically place students in essential organizations such as NIOSH, ATSDR, or CDC; (4) educate nurse educators; and (5) create environmental health awards in nursing. Nominal group technique facilitated the conversion of IOM conceptual competencies into a mission for nurses to recover the legacy of environmental health nursing and integrate it into mainstream nursing practice.

Acknowledgments

The RWJ Executive Nurse Fellows program provided support for the “Moving Upstream” environmental health and nursing course. Class participants included: Carolyn Wenger, Rebecca Spear, Esther Sherman, Maryann Prawdzienski, Sheila Arbury, Kathy Helmuth, Sharon Kelly, Stephanie Atherly, Linda Schwartz, Ann Shors, Ruth Gralow, Suzanne Brown, Mary Hoke, Terri Hocking, Laura Larsson, and Patricia Butterfield.

Contributor Information

Laura S. Larsson, Swinqle Student Health Center, College of Nursing, Bozeman, Montana.

Patricia Butterfield, Montana State University– Bozeman, College of Nursing, Bozeman, Montana.

References

- Association of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/EHN/

- Butterfield PG. Recovering a lost legacy: Nurses' leadership in environmental health. Journal of Nursing Education. 2000;39(9):385–386. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001201-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney O, McIntosh J, Worth A. The use of the nominal group technique in research with community nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:1024–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.09623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthorpe D, Harris D. Nominal group technique: Assessing staff concerns. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(7–8):11, 18, 37. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DC, Rhodes R, Baker AS. Curriculum revision: Reaching faculty consensus through the nominal group technique. Journal of Nursing Education. 1998;37(7):326–328. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19981001-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady PA, Harden JT, Moritz P, Amende LM. Incorporating environmental sciences and nursing research: An NINR initiative. Nursing Outlook. 1997;45:73–75. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(97)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Available: http://www.iom/edu/iom/

- Lloyd-Jones G, Fowell S, Bligh JG. The use of the nominal group technique as an evaluative tool in medical undergraduate education. Medical Education. 1999;33(1):8–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RH. Finding diamonds in the trenches with the nominal group process. Family Practice Management. 1999;6(5):49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope AM, Snyder MA, Mood LH, editors. Nursing, health and the environment: Strengthening the Relationship to improve the public's health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvela PD, Holcomb DR, Odulana JA. Designing a safety program for a college health service. Journal of American College Health. 1992;40(5):231–233. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.9936285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan G. Good characteristics of a clinical supervisor: a community mental health nurse perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30(3):713–722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven AH, Delbelq AL. The nominal group technique as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. American Journal of Public Health. 1972;69:337–342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]