Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between histories of childhood abuse and aggressive behaviors among adolescent girls involved in child welfare, and determined whether symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression mediated this relationship. Participants were 237 girls ages 12–19 years. Overall, results indicated 89 % of the adolescents endorsed at least one aggressive behavior towards others. Specifically, 72.0 % engaged in physical aggression, 78.5 % engaged in non-physical aggression, and 51.5 % endorsed relational aggression. Greater severity of emotional and physical abuse were significantly associated with a higher frequency of aggressive behaviors. Sexual abuse was not significantly related to aggression. Post-traumatic stress and depression fully mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and aggression, controlling for race, service use, and living situation. The linkages between physical abuse and aggression were not mediated by either post-traumatic stress or depression. Findings suggest that among adolescent girls with histories of emotional abuse, post-traumatic stress and depression represent potential modifiable risk factors to target for reducing aggression.

Keywords: Aggression, Emotional abuse, Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Adolescent girls, Mental health

Childhood abuse has profound long-term health and mental health consequences, and recent research indicates that the number of children who experienced substantiated or confirmed childhood abuse and neglect by 18 years old is 1 in 8 (Wildeman et al. 2014). Childhood abuse is a form of child maltreatment which includes any act or series of acts by a parent or other caregiver that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm (Leeb et al. 2008). Consistent with the theory on the “cycle of violence” (Widom 1989a), exposure to childhood abuse increases the intergenerational risk of engaging in violent or aggressive behaviors in adolescence and adulthood. Children with a history of childhood abuse, for example, were significantly more likely to have official records for juvenile delinquency, adult criminality, and violent criminal offenses (Widom 1989b), and the effect was stronger among abused girls in comparison to boys (Magdol et al. 1998; Maxfield and Widom 1996).

In a recent review of the relationship between childhood abuse and youth violence perpetration, Maas et al. (2008) identified several key findings. First, physical childhood abuse appears to be the most consistent predictor of youth violence perpetration in comparison to the other forms of abuse and neglect (Farrington 1989; Herrenkohl et al. 1997; Smith and Thornberry 1995; Widom 1989b). The interrelations between sexual abuse and perpetration are less consistent than physical childhood abuse, but it also remains a potential risk factor for future adolescent aggression (Maas et al. 2008). Emotional childhood abuse can also increase risk for future violence perpetration for youth who live in poverty and communities with higher rates of violence (Farrington 1989; Silva et al. 2014; Smith and Thornberry 1995; Zurbriggen et al. 2010). Last, childhood abuse, particularly for females in comparison to their male counterparts, can increase the risk for future intimate partner violence perpetration (Magdol et al. 1998). For example, emotional childhood abuse, including harsh parental disciplining, was associated with physical intimate partner violence perpetration for females only.

Pathways Between Childhood Abuse and Adolescent Aggression

Although researchers have been calling for theoretically-informed examinations of the developmental pathways connecting childhood abuse and adolescent aggression (Bender 2010; Hong et al. 2012; Maas et al. 2008), little research exists that examines the roles of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression as potential causal mechanisms or mediators. The extant literature provides consistent and compelling empirical evidence of the increased risk of PTSD (Arata 1999; Brewin et al. 2000; Lansford et al. 2002; Runyon and Kenny 2002; Widom 1999) and depression (Danielson et al. 2005; Stuewig and McCloskey 2005; Turner et al. 2006) after exposure to childhood abuse.

Multiple theoretical explanations, such as general strain theory, social control theory, and attachment theory, have been proposed to explain the connection between childhood abuse and future engagement in adolescent aggression (Maas et al. 2008). General strain theory, for example, predicts children exposed to adverse, traumatic experiences will have problems regulating their emotional states and identifying positive coping strategies, resulting in the overreliance on hostile and aggressive behaviors as a coping mechanism (Agnew 1999). Additionally, social control theory posits that the establishment of prosocial bonds or attachments inside and outside of the family system (e.g., parents, school, religion) control or inhibit deviant and aggressive behaviors (Hirschi 1969). In a longitudinal study, parental attachment, as measured by communication, trust, and closeness, was associated with less internalizing and externalizing behaviors including aggression (Buist et al. 2004). Consistent with social control theory, attachment theorists contend psychological functioning and the quality of peer relationships are determined to a great extent by early caregiver experiences and the successful development of secure parental attachments (Goldenson et al. 2007). Children who experience childhood abuse often fail to develop secure attachments and, as a result, perceive their care-givers as unavailable, unhelpful, or unresponsive in times of distress, which is linked to depression (Fonagy et al. 1996) and posttraumatic stress symptomology (Dutton et al. 1994; Swan and Snow 2006). Furthermore, the extant literature indicates that depression and posttraumatic symptomology are associated with higher levels of aggression and antisocial behavior (Kendra et al. 2012). In alignment with the aforementioned theories, the experience of childhood abuse appears to be an important link in a developmental pathway leading to the potential onset of PTSD and depression that can increase involvement in future aggressive behaviors.

In comparison to the general population, the child welfare population experiences a substantially larger number of traumatic events and has a higher prevalence of PTSD (Kolko et al. 2010). For example, 6 to 7 % of the general population of youth is estimated to meet the criteria for PTSD of re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event, and increased arousal (Merikangas et al. 2010) in comparison to 15 to 16 % of youth in foster care, and 22 % among females (McMillen et al. 2005; Salazar et al. 2013). In addition to PTSD, childhood abuse increases the risk of depression in childhood and in adulthood (Brown et al. 1999; Gibb et al. 2007). Depression appears to be associated equally with all forms of childhood abuse (Lansford et al. 2002). The higher prevalence rates of PTSD and depression within the child welfare population, coupled with our understanding of general strain theory and attachment theory, suggest the usefulness of exploring PTSD and depression as potential mediators explaining the relationship between childhood abuse and adolescent aggression in child welfare populations.

The purpose of the study was to describe the mental health pathways by which histories of child abuse lead to aggression (verbal, physical, and relational) among adolescent girls. Specifically, the following research questions were addressed: 1) What are the associations of types of childhood abuse (emotional, physical, sexual abuse) with current aggressive behaviors among adolescent girls involved in the child welfare system? and 2) Do mental health problems (symptoms of PTSD and depression) mediate this relationship in this population? Findings will contribute to our understanding of the pathways or mechanisms by which different types of childhood abuse increase the risk of aggressive behaviors during adolescence. Results will identify potential modifiable mental health symptoms to target for preventing violence among this population.

Methods

Subjects

Participants were 237 girls ages 12–19 years (M = 14.9, SD = 1.6) who had been involved with the child welfare system and who were recruited for a trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral intervention study. Baseline data collected for the group intervention study were used for the present analyses. The majority of participants were youths of color (75 %) who primarily were African-American (70 %), and the remaining adolescents were White, non-Hispanic (25 %). The majority of participants 88 % lived in non-congregate care (biological parent, relative, adoptive parent, foster homes) and the remainder lived in congregate or group homes. Participants were recruited through referrals from the state’s child protective agency (35 %), other agencies that provide services to adolescents in the child welfare system (54 %), and from caregivers (11 %). Inclusion criteria for the study included: 1) adolescent girls ages 12–19 years old, and 2) a history of maltreatment that had been formally investigated by the child protective services. Girls were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: were unable to read or write, were hospitalized for mental health problems in the last 6 months, were unable to tolerate discussing abuse or neglect, or had behaviors that would prohibit participation in a group treatment or interview.

Procedures

The study protocol was first approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of the two collaborating universities. Second, a Certificate of Confidentiality was issued by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the funding agency, to protect the privacy of research subjects by withholding their identities from all persons not connected with the research. Additionally, the Research Committee of the state office of child protective services approved the research protocol.

The consent procedures included several steps. After a referral was made to the study team and the adolescent expressed interest in participating, written consent was obtained by the legal custodian, which could be the biological parent, relative, adoptive parent, or the youth’s case manager. Additionally, to the fullest extent possible, the written consent of the members of the family support team (e.g., Guardian ad litem, Juvenile Officer, and child’s current therapist) was secured. All adolescents under the age of 18 provided written assent to participate in the study. Participants were given a $20 gift card to compensate them for their time.

Face-to-face interviews were administered by interviewers who were masters-level or doctoral-level social work students who participated in 8 h of interview training. The training included background knowledge of the population, basic interviewing skills, confidentiality and ensuring privacy during the interview, and procedures for reports of abuse and endorsing items related to suicide. Interviews were conducted in participant homes or a community-based mental health agency and took approximately 1 h to complete.

Variables and Measures

Childhood Abuse

The Child Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein and Fink 1998) was used to obtain participant’s reports of the types and severity of childhood abuse experienced. Three subscales from the CTQ-SF were used in the present study: emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. Items are rated from never true (1) to very often true (5). Previous research has demonstrated the validity and reliability of the CTQ-SF (Scher et al. 2001). Additionally, guidelines for classification of CTQ-SF scores are provided according to the following categories: None or minimal, low-moderate, moderate-severe, and severe-extreme (Bernstein and Fink 1998). Internal consistency alpha coefficients for the current sample were as follows: emotional abuse (r = 0.86), physical abuse (r = 0.87), and sexual abuse (r = 0.92).

PTSD Symptoms

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS; Foa et al. 2001). Seventeen items (e.g., Having bad dreams or nightmares; Trying not to think about, talk about, or have feelings about the trauma) assessed domains of re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal. Participants rated the frequency of post traumatic symptoms over the past month using a 4-point scale from “not at all” (0) to “five or more times a week” (4). The CPSS has previously demonstrated convergent validity, correlating highly with a similar PTSD scale (Foa et al. 2001). Good internal consistency and test-retest reliability have also been established (Foa et al. 2001). For the present study, internal consistency reliability was r = 0.90.

Depression

The Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 2003) was used to measure depressive symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. The 27 items were rated from 0 to 2 and summed, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Concurrent, discriminative, and criterion validity have been demonstrated (Kovacs 2003). Good internal consistency and test-retest reliability have been demonstrated for a child welfare population (Kolko et al. 2010). The internal consistency alpha coefficient for the current sample was r = 0.89.

Aggression Perpetration

The Aggression—Problem Behavior Frequency Scale (Farrell et al. 2000) was used to assess the participants’ engagement in aggressive behaviors towards others in the last 3 months. The 18-item scale measured physical aggression (e.g., Threw something at someone to hurt them); verbal or non-physical aggression (e.g., Insulted someone’s family); and relational aggression (e.g., Spreading a false rumor about someone). The current study modified the language in the items from “student” or “kid” to “person” or “someone” (i.e., “Spread a false rumor about someone;” “Shoved or pushed another person”) to assess aggressive behaviors beyond schools and peers. Items were rated to indicate the frequency with which they had happened over the past 3 months on a 6-point scale coded as follows: 1=‘0 times’, 2 = ‘1–2 times’, 3 = ‘3–5 times’, 4 = ‘6–9 times’, 5 = ‘10–19 times’, and 6 = ‘20+ times.’ Items were summed to yield a total aggression score with a possible range of 18 to 108. Previous studies have shown adequate to good internal consistency (Farrell et al. 2000). Internal consistency reliability for the current study was r = 0.93.

Potential Control Variables

Demographic variables such as age and race (0 = youths of color; 1 = white) were investigated as potential control variables. Several other control variables were also investigated because they have been shown in previous research to predict mental health and behavioral outcomes among child welfare populations, such as current living situation, and use of services. Current living situation was coded into: 0 = non-congregate care (i.e., biological family, foster family, relative care) and 1 = congregate care (group home).

The number of services used in the participant’s lifetime was measured using the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA; Stiffman et al. 2000). This structured interview asks about the number and types of inpatient, out-patient, and school-based social, behavioral, and mental health services the participant has ever received.

Data Analysis

The mediating roles of PTSD and depression were tested using the steps established by Baron and Kenny (1986), followed by the bootstrapping technique to test the significance of the indirect effects described by Preacher and Hayes (2004). First, a preliminary analysis was conducted to determine that there were significant correlations among the hypothesized predictor, mediator, and outcome variables. Second, a mediation analysis was conducted using the Hayes (2013) PROCESS SAS macro. In addition to calculating the standard a, b, c, and c’ path coefficients, the Hayes macro uses a bootstrap re-sampling methodology to enable a significance test of the indirect effect (the impact of the predictor on the outcome variable through the mediator).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

According to the classification of CTQ-SF subscale scores by Bernstein and Fink (1998), the girls in the current study experienced emotional abuse in the low to moderate range (M = 12.1, SD = 6.0), physical abuse in the moderate to severe range (M = 11, SD = 5.8), and sexual abuse in the severe range (M = 12.6, SD = 7.4).

Results indicated that 51 % of the girls experienced PTSD symptoms above the clinical cut-off scores (≥15), with a mean score of 16.9 (SD = 10.9) for the entire sample. The participants’ mean depression score was 12.0 (SD = 8.6), and 21 % of the girls reported depressive symptoms ≥ 17, a clinical cutoff score defined as at or above the 85th percentile in the normative sample (Kovacs 2003).

Overall, results indicated 89 % of the sample engaged in one type of aggressive behavior towards others (based on endorsing one item of the total scale). Specifically, 72 % endorsed at least one item related to physical aggression, 78.5 % endorsed non-physical aggression, and 51.5 % endorsed relational aggression. The frequencies of each aggression item that were experienced in the last 3 months are shown in Table 1. Notably, 11 % (n = 27) threatened someone with a weapon, 51 % (n = 121) shoved or pushed a peer, and 50 % (n = 118) hit or slapped a peer.

Table 1.

Frequencies and percentages of physical, non-physical, and relational aggression (N = 237)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Aggression | ||

| Thrown something at someone to hurt them? | 70 | 30 |

| Been in a fight in which someone was hit? | 102 | 43 |

| Threatened to hurt a teacher? | 22 | 9 |

| Shoved or pushed another kid? | 121 | 51 |

| Threatened someone with a weapon (gun, knife, club, etc.)? | 27 | 11 |

| Hit or slapped another kid? | 118 | 50 |

| Threatened to hit or physically harm another kid? | 88 | 37 |

| Non-Physical Aggression (Verbal and Non-Verbal) | ||

| Insulted someone’s family? | 40 | 17 |

| Teased someone to make them angry? | 88 | 37 |

| Put someone down to their face? | 62 | 26 |

| Gave mean looks to another student? | 169 | 71 |

| Picked on someone? | 84 | 35 |

| Relational Aggression | ||

| Didn’t let another student be in your group anymore because you were mad at them? | 65 | 27 |

| Told another kid you wouldn’t like them unless they did what you wanted them to do? | 18 | 8 |

| Tried to keep others from liking another kid by saying mean things about him/her? | 40 | 17 |

| Spread a false rumor about someone? | 22 | 9 |

| Left another kid out on purpose when it was time to do an activity? | 54 | 23 |

| Said things about another student to make other students laugh? | 91 | 38 |

Aggression total M (SD) = 28.2 (13.3)

Bivariate and Mediation Analyses

Bivariate analyses were conducted between independent, mediating, and dependent variables to determine if they met the criteria to test the mediating hypothesis. Bivariate correlations shown in Table 2 indicated that greater severity of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse was significantly associated with higher levels of PTSD and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, significant relationships were also found between emotional and physical abuse with aggression; higher levels of emotional and physical abuse were associated with a higher frequency of aggressive behaviors. However, even though the bivariate relationship between physical abuse and aggression was significant (r = .15, p < .05), the total effect model, which included the control variables of service use (β = 1.27, p < .001), race (β = −4.53, p < .05), and living situation (β = 4.98, p < .10), indicated that physical abuse was no longer significantly related to aggression (β = .10, p = .52). Therefore, the criteria were not met for testing the mediating effect of PTSD or depression on the pathway between physical abuse and aggression. Additionally, because sexual abuse was not associated with aggression at the bivariate level, no further analysis was conducted to examine the mediators between sexual abuse and aggression. Last, service use, race, and living situation were significantly associated with emotional abuse and aggression at the bivariate level, and therefore were used as control variables in the mediating models.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between childhood abuse, mental health, aggression, and potential control variables (N = 237)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional abuse | – | |||||||||

| 2. Physical abuse | .69*** | – | ||||||||

| 3. Sexual abuse | .38*** | .30*** | – | |||||||

| 4. PTSD | .45*** | .24*** | .32*** | – | ||||||

| 5. Depression | .39*** | .15* | .25*** | .75*** | – | |||||

| 6. Aggression | .28*** | .15* | .10 | .40*** | .44*** | – | ||||

| 7. Age | .09 | .10 | .04 | −.08 | −.01 | .10 | – | |||

| 8. Race | .16* | .02 | .13* | .05 | .07 | −.14* | .04 | – | ||

| 9. Living situation | .15* | .21** | .04 | .04 | .07 | .23*** | .20** | −.06 | – | |

| 10. Service use | .38*** | .36*** | .21** | .19** | .18** | .29*** | .19** | .07 | .37*** | – |

Race (0 = youths of color; 1 = white); Living Situation (0 = non-congregate care; 1 = congregate care)

p ≤ .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

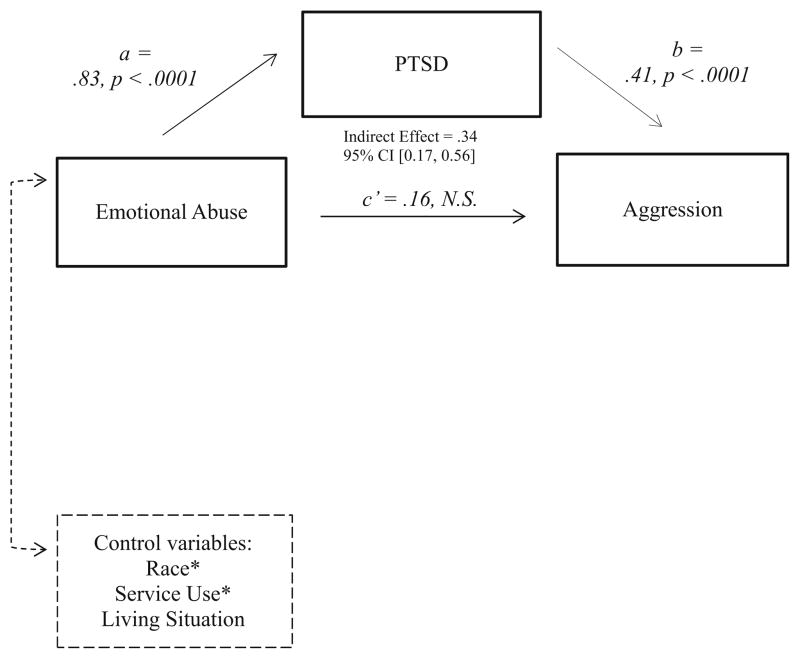

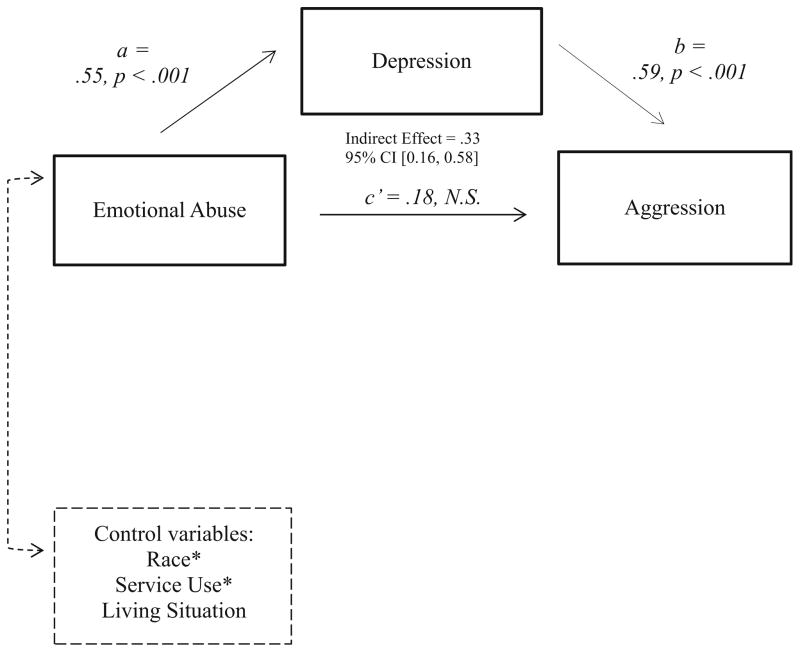

Results testing the mediators between emotional abuse and aggression are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Mediation analyses indicated that participants with greater emotional abuse were associated with increased aggressive behaviors, and this pathway was fully mediated by PTSD (i.e., the c’ path becomes non-significant with PTSD in the model). Results of the bootstrapping analysis described by Preacher and Hayes (2004) indicated significant indirect effects of emotional abuse on aggressive behaviors via the hypothesized mediator of PTSD, β = .34, 95 % CI [0.17, 0.56]. Likewise, as shown in Fig. 2, the same pattern emerged; depression also fully mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and aggression. Results indicated a significant indirect effect of emotional abuse on aggressive behaviors, β = .33, 95 % CI [0.16, 0.58]. In both models examining the pathways from emotional abuse to aggression, youths of color and youths who received more lifetime services displayed higher levels of aggression.

Fig. 1.

Mediation analysis testing PTSD as a pathway between childhood emotional abuse and aggression in adolescent girls (N = 237). Note. * Significant covariate

Fig. 2.

Mediation analysis testing depression as a pathway between childhood emotional abuse and aggression in adolescent girls (N = 237). Note. * Significant covariate

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that adolescent girls who report more severe histories of childhood emotional abuse engage in significantly higher frequencies of aggressive behaviors than those with lower levels of emotional abuse, and this relationship is fully mediated by both PTSD and depression. Emotional abuse in the current study included items such as “… my parents wished I had never been born” or “… someone in my family hated me” (Bernstein and Fink 1998). These findings provide support for a developmental pathway bridging experienes of childhood emotional abuse with adolescent aggression. Consistent with social control theory and attachment theory, emotional abuse could disrupt the development of prosocial parental bonds and secure attachments, leading to depression and PTSD. These mental health consequences can contribute to aggressive behaviors towards others as a strategy to protect themselves against harm (Bender 2010). In addition to social control theory and attachment theory, many other hypotheses have been proposed to explain the connection between child abuse and adolescent aggression. For example, adolescent aggression might be a learned behavior through direct or witnessed violent interactions (Burton et al. 2002), or the result of a cognitive bias for interpreting the intentions or motives of peers as hostile in ambiguous social situations (Dodge 2006). The extant literature, including the current study, provide little empirical evidence for a single explanation for the association between child abuse and future aggression (Maas et al. 2008). Overall, aggression is best understood as a complex interaction between the adolescent and her environment, with the mental health consequences of child abuse (depression and posttraumatic stress) playing an important role in understanding aggression among girls in the child welfare system.

In the current study, adolescents who reported histories of sexual abuse reported higher symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression, yet there was no significant relationship between sexual abuse and aggressive behaviors, even at the bivariate level. Previous research suggests females are more likely to respond to childhood sexual abuse with internalizing behaviors, such as depression, rather than externalizing behaviors such as aggression towards others (Turner et al. 2006), and that victims of childhood sexual abuse are almost twelve times as likely to be revictimized than those who were not abused (Boney-McCoy and Finkelhor 1995). Not surprisingly, many of the previous investigations of the effects of childhood abuse have focused on the increased risk of revictimization rather than on aggression towards others. For example, children who were maltreated were 6.7 times more likely to be revictimized and 6.9 times more likely to be sexually revictimized (Finkelhor et al. 2007). Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect have all been associated with peer victimization (Duncan 1999). Our finding that sexual abuse was not associated with aggression should be interpreted with caution because we did not account for abuse characteristics in our study, such as duration and chronicity, and the girl’s relationship to the perpetrator (Maas et al. 2008; Thornberry et al. 2001), all of which may influence an adolescent’s risk for aggression.

Evidence for testing the mediating role of PTSD and depression as pathways from physical abuse to aggression was not supported in the current study since the unique association between physical abuse and aggression became non-significant when the control variables were entered in the model. This finding is inconsistent with research by Fagan (2005) and Herrenkohl et al. (1997); however, differences in how child maltreatment outcomes were defined and sample differences in prior studies (i.e., IPV perpetration among young adults, violent crimes among adolescents) may have accounted for the lack of consistent results. Interestingly, in the current study’s sample of adolescent girls in child welfare, who were predominately urban and African American, girls who used more services and girls of color engaged in a significantly higher frequency of aggressive behaviors than their counterparts. Additionally, higher service use was associated with greater severity of all types of abuse, and higher levels of PTSD and depression. Essentially, adolescents who experience more mental health and behavioral problems are also receiving more services. Because there were no racial differences in severity of abuse or mental health symptoms among study participants, the modest higher frequency of aggressive behaviors found among girls of color cannot be explained by abuse or mental health histories. Although little research has examined race and ethnic differences in aggression by gender, the literature has focused primarily on social, institutional, and community-level characteristics in explaining this racial/ethnic disparity in rates of aggression (Miller-Johnson et al. 2012). For example, poverty and less access to economic and educational opportunities during adolescence and young adulthood are seen as key explanatory factors in higher rates of aggression among African American boys and girls. Coie and Jacobs (1993) have also suggested a range of other possible factors: limited social resources, high neighborhood crime rates, fewer connections to communities and schools, and weak intergenerational bonds. There might be other culturally specific factors (e.g., minority stress) that explain the relationship between race and aggression among adolescent girls in child welfare, and these should be explored in future studies.

The findings from this study suggest that reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression among girls who have histories of emotional abuse may reduce or prevent aggressive behaviors during adolescence. Unfortunately, evidence suggests that emotional abuse may be overlooked in child protection investigations. A study of case records of maltreated urban adolescents found that although 50 % of the sample had experienced emotional abuse, only 9 % were identified as emotionally abused at the time of referral to child protective services (Trickett et al. 2009). Failure to capture exposure to emotional abuse during child abuse investigations may prevent children and adolescents from receiving proper referral and treatment services for their unique maltreatment histories. Moreover, despite the strong evidence that childhood abuse increases the risk of long lasting mental, physical, and behavioral health problems, and the knowledge that children in the child welfare system are disproportionately exposed to trauma, integrating evidence-based trauma treatments into child welfare has been challenging (Kessler et al. 2005; Maher et al. 2009). Several organizational barriers that have been identified include heavy caseloads and time constraints of child welfare workers, lack of staff, and limited resources (Kramer et al. 2013). Recently, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has developed a toolkit that contains resources for disseminating evidence-based interventions for treating trauma in child welfare involved populations (Chadwick Center for Children and Families and the United States of America 2013). Recommended strategies include increasing child welfare workers’ awareness of the effects of trauma on children’s emotional and behavioral well-being, promoting comprehensive trauma-focused mental health assessments, and implementing evidence-based trauma treatment for this population. In accordance with the main findings from the current study, this toolkit may be used to enhance child welfare workers’ knowledge and screening of emotional abuse, depression, PTSD, and aggressive behavior among investigated adolescents, as well as referral to appropriate trauma treatments. Additionally, future research is needed to evaluate the effects of evidence-based treatments, not only on mental health outcomes such as PTSD and depression, but on behavioral outcomes that include aggression in child welfare populations.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, cross-sectional data were utilized to determine the relationships between childhood abuse, symptoms of PTSD and depression, and aggressive behaviors, and a longitudinal design would have been more rigorous. Second, our measure of physical, verbal, and relational aggression did not specify who was the victim or target of the youths’ aggression; it could have been a peer, family member, or some other person, since the items use the word “someone” or “person” as the target of aggression. Additionally, it is important to note that the adolescents who participated in the current study were not a representative sample of girls served by the child welfare system, but a convenience sample of those who were referred for a trauma-focused group treatment. However, the current study’s findings may be generalized to adolescent girls who are seeking treatment for exposure to traumatic events, including childhood abuse. Furthermore, because we did not use a clinical cut-off score for either PTSD or depression as inclusion criteria, the current sample may be more representative of a general child welfare sample of female adolescents than a clinical sample would be. Last, because the purpose of the current study was to compare the mediating pathways of three types of abuse leading to aggression, we did not examine the impact of co-occurring types of abuse. It may be argued that examining single types of abuse does not mirror reality, since often girls in child welfare experience multiple forms of abuse. Additionally, the current study did not assess the characteristics of the child abuse and its relation to aggressive behaviors. For example, prior research suggests that an adolescent has more serious consequences when the childhood abuse is persistent, and occurs at an older age (Thornberry et al. 2001). Further investigation of the abuse characteristics may be important to understanding the pathways from abuse to aggression in this population.

Despite these limitations, the current study has several strengths. The current study’s reporting of histories of abuse is more accurate than retrospective reports in that the current study’s sample was formally investigated by workers from child protective services. Also, identifying mediating pathways during adolescence rather than in adults provides information that may be useful to prevent the perpetration of dating and intimate partner violence in adulthood. Another strength of the study is the ability to compare pathways from different types of childhood maltreatment to aggressive behaviors in adolescence. Of the studies that have compared types of child maltreatment and the linkages to aggression, few have conducted mediating analyses, and examined girls involved in child welfare. Furthermore, the current study includes emotional abuse, an often overlooked type of abuse, despite some recent evidence that the effects of emotional abuse are considered disabling and enduring (Riggs 2010; Shaffer et al. 2009). Last, the current study’s measure of abuse used a continuous scale instead of a single dichotomous item that allowed us to capture the severity of the abuse.

This study highlights the need for more theoretically-informed examinations of mental health mechanisms that might be able to explain the association between childhood abuse and engagement in higher rates of adolescent aggression. The major finding of this study indicates that PTSD and depression fully mediate the association between emotional abuse and aggression. The child welfare system and other service providers may reduce the risk of aggression among adolescent girls through training to increase awareness of emotional abuse, as well as targeted assessment and referral to evidence-based treatment of depression and PTSD. Further research is needed to confirm the results of the current study, as well as to identify additional modifiable factors that may help to explain the relationship between other forms of childhood abuse, such as physical abuse and aggression, in adolescents involved in the child welfare system.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant No. 1R49CE001510 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention awarded to Washington University. The authors would like to acknowledge Children’s Division of Missouri of St. Louis City and County, and Jefferson County. Portions of this paper were presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting (2012) in San Francisco, CA.

References

- Agnew R. A general strain theory of community differences in crime rates. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1999;36:123–155. [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM. Sexual revictimization and PTSD: an exploratory study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1999;8(1):49–65. doi: 10.1300/J070v08n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender K. Why do some maltreated youth become juvenile offenders?: A call for further investigation and adaptation of youth services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Psychosocial sequelae of violent victimization in a national youth sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(5):726–736. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(5):748–766. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: specificity and effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(12):1490–1496. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Deković M, Meeus W, van Aken MAG. The reciprocal relationship between early adolescent attachment and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(3):251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DL, Miller DL, Shill CT. A social learning theory comparison of the sexual victimization of adolescent sexual offenders and nonsexual offending male delinquents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26(9):893–907. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick Center for Children Families the United States of America. Creating trauma-informed child welfare systems: A guide for administrators. 2. San Diego, CA: Chadwick Center for Children and Families; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Jacobs MR. The role of social context in the prevention of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5(1–2):263–275. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson CK, de Arellano MA, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Resnick HS. Child maltreatment in depressed adolescents: differences in symptomatology based on history of abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(1):37–48. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Translational science in action: hostile attributional style and the development of aggressive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18(03):791–814. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RD. Maltreatment by parents and peers: the relationship between child abuse, bully victimization, and psychological distress. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4(1):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, Saunders K, Starzomski A, Bartholomew K. Intimacy-anger and insecure attachment as precursors of abuse in intimate relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24(15):1367–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb01554.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA. The relationship between adolescent physical abuse and criminal offending: support for an enduring and generalized cycle of violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(5):279–290. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-6604-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kung EM, White KS, Valois RF. The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29(2):282–292. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence and Victims. 1989;4(2):79–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Re-victimization patterns in a national longitudinal sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:479–502. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Johnson KM, Feeny NC, Treadwell KR. The child PTSD symptom scale: a preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2001;30(3):376–384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, Steele H, Kennedy R, Mattoon G, … Jones EE. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(1) doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatients. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24(4):256–263. doi: 10.1002/da.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson J, Geffner R, Foster SL, Clipson CR. Female domestic violence offenders: their attachment security, trauma symptoms, and personality organization. Violence and Victims. 2007;22(5):532–545. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl RC, Egolf BP, Herrenkohl EC. Preschool antecedents of adolescent assaultive behavior: a longitudinal study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(3):422–432. doi: 10.1037/h0080244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Espelage DL, Grogan-Kaylor A, Allen-Meares P. Identifying potential mediators and moderators of the association between child maltreatment and bullying perpetration and victimization in school. Educational Psychology Review. 2012;24(2):167–186. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9185-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendra R, Bell KM, Guimond JM. The impact of child abuse history, PTSD symptoms, and anger arousal on dating violence perpetration among college women. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27(3):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9415-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler ML, Gira E, Poertnew J. Moving best practice to evidence-based practice in child welfare. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2005;86(2):244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Hurlburt MS, Zhang J, Barth RP, Leslie LK, Burns BJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents referred for child welfare investigation a national sample of in-home and out-of-home care. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(1):48–63. doi: 10.1177/1077559509337892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory (CDI): Technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L, Sigel BA, Conners-Burrow NA, Savary PE, Tempel A. A statewide introduction of trauma-informed care in a child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(8):824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb RT, Paulozzi L, Melanson C, Simon T, Arais I. Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maas C, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C. Review of research on child maltreatment and violence in youth. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2008;9(1):56–67. doi: 10.1177/1524838007311105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: a prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(3):375–389. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher EJ, Jackson LJ, Pecora PJ, Schultz DJ, Chandra A, Barnes-Proby DS. Overcoming challenges to implementing and evaluating evidence-based interventions in child welfare: a matter of necessity. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen CJ, Zima BT, Scott LD, Jr, Auslander WF, Munson MR, Ollie MT, Spitznagel EL. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(1):88–95. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Moore BL, Underwood MK, Coie JD. African-American girls and physical aggression: Does stability of childhood aggression predict later negative outcomes. In: Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster CW, Levene KS, editors. The development and treatment of girlhood aggression. 2. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012. pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs SA. Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: what theory and research tells us. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:5–51. doi: 10.1080//10926770903475968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon MK, Kenny MC. Relationship of attributional style, depression, and posttrauma distress among children who suffered physical or sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7(3):254–264. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar AM, Keller TE, Gowen LK, Courtney ME. Trauma exposure and PTSD among older adolescents in foster care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(4):545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0563-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJG, McCreary DR, Forde DR. The childhood trauma questionnaire in a community sample: psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Trauamatic Stress. 2001;14(4):843–857. doi: 10.1023/A:1013058625719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Yates TM, Egeland BR. The relation of emotional maltreatment to early adolescent competence: developmental processes in a prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva TC, Grana JL, Gonzalez-Cieza L. Self-reported physical and emotionall abuse among youth offenders and their association with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: a preliminary study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2014;58(5):590–606. doi: 10.1177/0306624X12474975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33(4):451–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1995.tb01186.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Compton W, III, Cottler L, Bean DL, … Weisz JR. The service assessment for children and adolescents (SACA): Adult and child reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(8):1032–1039. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuewig J, McCloskey LA. The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(4):324–336. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. The development of a theory of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(11):1026–1045. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(4):957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Mennen FE, Kim K, Sang J. Emotional abuse in a sample of multiply maltreated, urban young adolescents: issues of definition and identification. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(1):13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989a;244(4901):160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989b;59(3):355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen EL, Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. Childhood emotional abuse predicts late adolescent sexual aggression perpetration and victimization. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:204–223. doi: 10.1080/10926770903539631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]