Abstract

Host defense peptides (HDPs) play a critical role in innate immunity. Specific modulation of endogenous HDP synthesis by dietary compounds has been regarded as a novel approach to boost immunity and disease resistance in animal production. 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (1,25D3) is well known as a powerful HDP inducer in humans, but limited information about the effect of 1,25D3 on HDPs in poultry is available. Here, we sought to examine whether 1,25D3 could stimulate avian β-defensin (AvBD) expression in chickens. We used chicken embryo intestinal epithelial cells (CEIEPCs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to study the effect of 1,25D3 on the expression of AvBDs. We observed that 1,25D3 is able to up-regulate the expression of several AvBDs in CEIEPCs and PBMCs, whereas it increased the amounts of AvBD4 mRNA in CEIEPCs only in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). On the other hand, LPS treatment not only inhibited the expression of CYP24A1 but also altered the expression pattern of VDR in CEIEPCs. Furthermore, AvBDs were not directly regulated by 1,25D3, as cycloheximide completely blocked 1,25D3-induced expression of AvBDs. Our observations suggest that 1,25D3 is capable of inducing AvBD gene expression and is a potential antibiotic alternative through augmentation of host innate immunity as well as disease control in chickens.

Introduction

Host defense peptides (HDPs) are a group of cationic amphipathic peptides with less than 100 amino acid residues. They are important immune molecules that are able to kill a broad range of microbes, including viruses, Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria, fungi, protozoa and parasites. Besides those broad-spectrum antibiotic activities, they also play important roles in adaptive immunity, wound healing and sperm fertilization [1–3]. In birds, avian β-defensins (AvBDs) are the biggest cluster of host defense peptides, these peptides consist of a signal peptide, short propiece and conserved mature peptide. There are a total of 14 chicken AvBDs located on chromosome 3 and expressed in a wide array of tissues [4–6].

In order to meet the increasing demands for meat, antibiotics have been used in animal production since 1950s. Although antibiotic use is an effective way of improving animal feed efficiency, preventing disease, and controlling infections, routine use of antibiotics in-feed has been criticized for triggering the emergence of drug-resistant microbes and contamination of food products and environment with unwanted antibiotic residues [7–9]. Numerous countries have implemented bans on the use of low dose of antibiotics as feed additive [10]. Therefore, antibiotic alternatives are urgently needed to ensure animal health and food safety. HDPs are attractive candidates as alternatives to antibiotics as they have the potential to control a broad spectrum of pathogens without eliciting resistance. However, high production cost and peptide instability limit direct use of HDPs as effective antibiotics alternatives in animals [1]. Recently, several nutrients have been found to be highly potent in augmenting HDP synthesis and enhancing disease resistance [11–15], suggesting a high-efficiency and low-cost strategy for antimicrobial therapy. Furthermore, because those compounds come from dietary source and have no direct interaction with pathogens they provoke no inflammatory response. Hence, dietary supplementation of HDP-inducing compounds is considered as a high efficiency strategy to enhance animal immunity.

Vitamin D3 (Vit-D3), also called cholecalciferol, is a sterol that can be obtained from dietary sources. After absorbed, the bioactive mechanism of dietary Vit-D3 contains two hydroxylated steps. The initial hydroxylation (25-hydroxylase) takes place in liver, where 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (25OHD3) is formed. The final hydroxylation occurs in kidney, bone, prostate and immunocytes by 1α-hydroxylases which convert 25OHD3 into 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin-D3 (1,25D3), the most biologically active hormonal metabolite of Vit-D3 [16, 17]. Apart from its typical action in regulating calcium phosphorus homeostasis and bone mineralization, 1,25D3 is known to enhance the expression of HDPs and strengthen host innate immunity in various species. In human, 1,25D3 dramatically induce the expression of cathelicidin (LL-37) and defensins in different cell types [11, 18]. In bovine, although no evidence shows that 1,25D3 stimulate the production of cathelicidins, the expression of several HDPs such as β-defensins [19, 20] S100A7 [20] and S100A12 [21] are increased by 1,25D3. In chickens, previous studies showed that feed or injection of VIT-D3 can induce the expression of some HDPs in different tissues and conditions in vivo [22–24]. However, there is no direct evidence to indicate that Vit-D3 boost the expression of AvBDs through 1,25D3. Likewise, to our knowledge, there is no report about the effect of 1,25D3 on the expression of chicken AvBDs in vitro. In the present study, we report 1,25D3 is capable of inducing the expression of AvBDs in chicken embryo intestinal epithelial cells (CEIPCs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Furthermore, we reveal that 1,25D3-induced expression of AvBDs in chickens is a secondary response to 1,25D3. These findings are vital in the development of antibiotic alternatives and disease prevention in poultry production.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatments

CEIEPCs were prepared and cultured according to a previous method [25]. Briefly, 15-days-old chicken embryos were obtained from Beijing Merial Vital Laboratory Animal Technology Co, LTD. Beijing, China. Small intestines were separated and cut into small pieces prior to being digested with type I collagenase (200 U/mL, Sigma Aldrich) and hyaluronidase (100 U/mL, Sigma Aldrich) at 37°C. Then the cells were collected by centrifugation at 500×g for 10 min. After that, all cells were resuspended in 10 mm plates and incubated in complete DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 20 μg/L epidermal growth factor (Sigma Aldrich), 100 mg/L heparin sodium (Sigma Aldrich), 110 mg/L pyruvate (Sigma Aldrich), 2.5 mg/L insulin (Sigma Aldrich), 200 mM glutamic acid (Sigma Aldrich), 100 U/L penicillin (Hyclone) and 100 μg/L streptomycin (Hyclone) for 24h. Last, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5×105 and cultured in 37°C under 5% CO2 overnight, prior to stimulation. PBMCs were isolated and cultured as previous descripted [12]. For signaling studies, PBMCs were pretreated with 10 μg /mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for 1h, followed by stimulation with 1.25D3. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Sichuan Agricultural University under permit number DKY-S20123120. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 055:B5 (Sigma Aldrich) was solubilized in endotoxin-free water. 1,25D3 (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved and diluted to different concentrations by 100% ethanol. For each treatment, 1 μL of solution with different doses of 1,25D3 was added into the cell culture medium. Cycloheximide (Santa Cruz) was also diluted in 100% ethanol and equal amount of 100% ethanol alone was added to the controls to balance the effect of ethanol.

CCK-8 viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by using CCK-8 (Shanghai Bestbio Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). CEIEPCs were seeded at a density of 5×104 cells/well in 96-well plates. At the indicated times, CCK-8 was added and incubated for 2h at 37°C for color development. The degree of the color was directly proportional to the number of viable cells. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated by RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio Inc., Dalian, China) and dissolved in RNase-free water. PrimeScript® RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio Inc., Dalian, China) was used for reverse transcription reaction and performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences, annealing temperature and accession numbers are shown in Table 1. The total volume of PCR contained 1 μL of cDNA, 0.8 μL 10 pmol/μL of each primer, 12.5 μL SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio Inc., Dalian, China) and double-distilled H2O to 25 μL. The optimum thermal cycling procedure was 95°C for 2min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5s, n°C for 30s (n is the annealing temperature), and 60°C for 30s. GAPDH was used as the reference gene and relative quantification of mRNA transcripts was accomplished using the 2-ΔΔCt method [26]. For each experiment, the control samples were used as the calibrator, and expression of each gene is reported as fold increase relative to the controls.

Table 1. Detail information of primers used in real-time PCR analysis.

| Primer | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Fragment length (bp) | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Accession numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AvBD-1 | GGATGCACGCTGTTCTTGGT | TCCGCATGGTTTACGTCTGTC | 100 | 60 | NM_204993.1 |

| AvBD-2 | CTGCTTCGGGTTCCGTTCCT | TGCTGCTGAGGCTTTGCTGTA | 127 | 60 | DQ677633.1 |

| AvBD-3 | AGGATTCTGTCGTGTTGGGAGC | TTCCAGGAGCGAGAAGCCAC | 143 | 62 | NM_204650.2 |

| AvBD-4 | GGCTATGCCGTCCCAAGTATT | CCAAATCCAACAATGCAAGAAG | 106 | 60 | NM_001001610.2 |

| AvBD-5 | AGCCGATGGTATTCCTGATGG | TGGTGATTGTTGCCTCTGGTG | 107 | 61 | NM_001001608.2 |

| AvBD-6 | TGGCAGTGGACTAAAATCTTGC | TTTCACAGGTGCTGATAGGGA | 197 | 59 | NM_001001193.1 |

| AvBD-7 | ATGGAATAGGCTCTTGCTGTG | GCCAGATAGAATGGAGTTGGAG | 119 | 58 | NM_001001194.1 |

| AvBD-8 | CGACTAATGTTCGCCAGGACC | TCTCTTCTGTTCAGCCTTTGGTG | 154 | 61 | NM_001001781.1 |

| AvBD-9 | AACACCGTCAGGCATCTTCACA | CGTCTTCTTGGCTGTAAGCTGGA | 131 | 62 | NM_001001611.2 |

| AvBD-10 | AACTGCTGTGCCAAGATTCCG | AGGAGGAATCCATCACAATCAGC | 112 | 62 | NM_001001609.1 |

| AvBD-11 | AGTCTGCAATTCGTTAGAGGCG | GGATGTGGTTTCCAAGGGTTTA | 180 | 61 | NM_001001779.1 |

| AvBD-12 | CACCAACTCCCACCAAGACCT | AAGTGAATCCACAGCCAATGAGA | 144 | 60 | NM_001001607.2 |

| AvBD-13 | AGCTGTGCAGGAACAACCATG | CAGCACTGAATGTTTAGGGTTGG | 143 | 60 | NM_001001780.1 |

| AvBD-14 | TGTCGGAAGATGAAGGGCAA | GCCAGTCCATTGTAGCAGGT | 83 | 59 | AM402954.1 |

| CYP24A1 | CGGTAGAAACGCTGCATTCAG | TAGGGCCGTCATTAGTCAAGC | 94 | 60 | NM_204979.1 |

| VDR | AGAAGCAAATTCAGCAGCAGGA | AAGGCATCGGAGCCAAAGAC | 101 | 60 | NM_205098.1 |

| IL-1β | ACTGGGCATCAAGGGCTA | GGTAGAAGATGAAGCGGGTC | 131 | 56 | NM_204524.1 |

| TLR-4 | ACTGTCAAGGCTGAGAACGG | AGCTGAGGGAGCTGAGATGA | 204 | 58 | NM_204305.1 |

| GAPDH | CCAGAACATCCCAAGCGTC | GGCAGGTCAGGTCAACAACAGA | 134 | 60 | NM_204305.1 |

Data Analysis

All data is shown as Means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS (version9.3) software and differences in ΔΔCT values among the different treatments were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey tested. The P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of target genes in CEIPCs

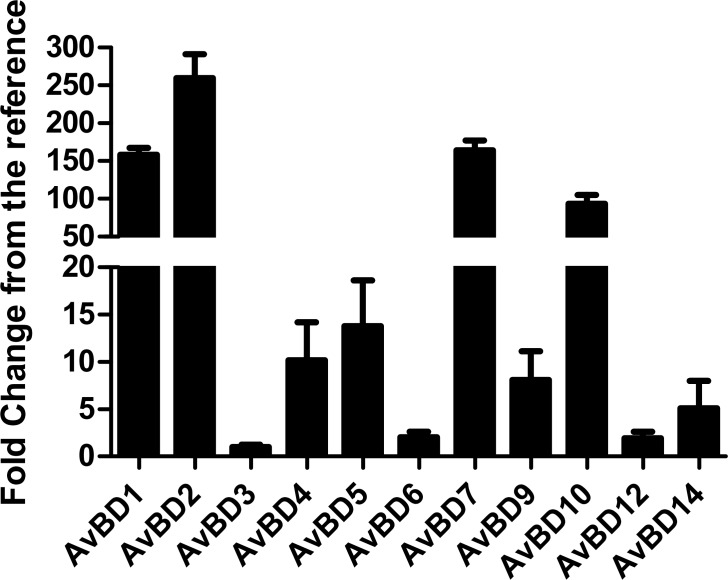

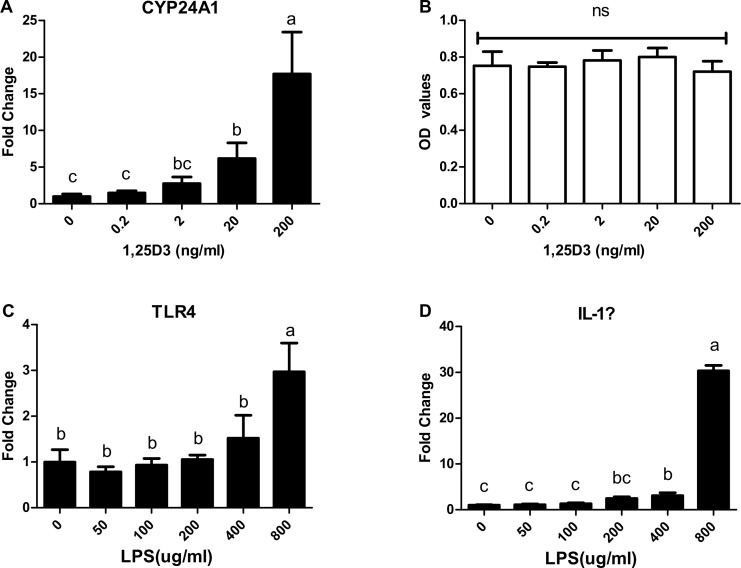

Prior studies in our lab demonstrated that injection of Vit-D3 is able to modulate AvBD gene expression in intestinal tissues [23]. To confirm the previous results, CEIEPCs were used as a model to evaluate the action of 1,25D3 on the expression of AvBDs with or without LPS. Basal expression levels of AvBDs are shown in (Fig 1). The expression of AvBD8, AvBD11 and AvBD13 was not detected in CEIEPCs within the 40 real-time PCR cycles. By contrast, the other 11 AvBDs were expressed in chicken CEIEPCs (Fig 1). Of those, the mRNA of AvBD1, AvBD2 and AvBD10 were more abundant, while AvBD3, AvBD6 and AvBD12 were expressed at lower levels. In order to ensure CEIEPCs are responsive to 1,25D3 and LPS, cells were treated with increasing doses of 1,25D3 or LPS. As illustrated in Fig 2A, 1,25D3 influenced 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) expression in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with controls, 200 ng/mL of 1,25D3 robustly induced CYP24A1 (>15 fold) expression in CEIEPCs, while the cell viability was not significantly influenced by different concentrations of 1,25D3 (P > 0.05) (Fig 2B). The expression of toll-like receptors (TLR)-4 and interleukin (IL)-1β were not significantly up-regulated by LPS until its concentration reached to 800 μg /mL and 400 μg/mL, respectively (Fig 2C and 2D). Since 800 μg/mL is a relative high dose of LPS concentration, we did not try a higher dose of LPS in this study.

Fig 1. Relative expression levels of AvBDs in CEIEPCs.

CEIEPCs were incubated with complete medium for 12h, followed by RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR analysis of all 14 AvBDs. Expression levels of all AvBDs were calculated relative to that of AvBD3 using GAPDH as a reference gene. Each bar represents mean ± SD of the results from two independent experiments performed in triplicate. AvBD8, AvBD11, and AvBD13 were not reliably detected within 40 real-time PCR cycles, and therefore, were not shown.

Fig 2.

Effect of 1,25D3 on the expression of CYP24A1 (A) and the growth (B) of CEIEPCs. CEIEPCs were incubated with indicated concentrations of 1,25D3 for 12h. Effect of LPS on the expression of TLR4 (C) and IL-1β (D) in CEIEPCs. CEIEPCs were incubated with indicated concentrations of LPS for 12h. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 2–3 independent experiments. The bars without the same letter indicate differences significant at P < 0.05.

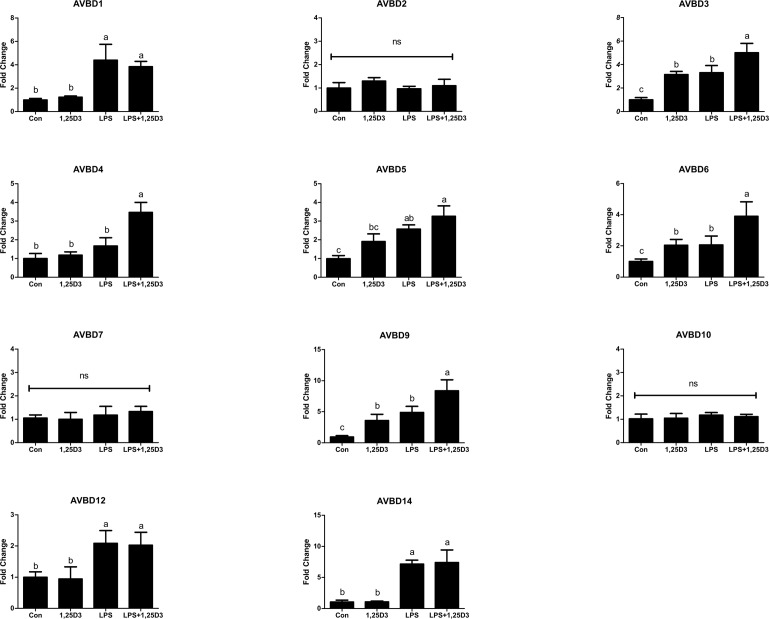

Effect of 1,25D3 combined with LPS on the expression of AvBDs in CEIEPCs

Along with the above analysis, CEIEPCs were treated with 20 ng/mL of 1,25D3 alone or in conjunction with 800 μg/mL LPS for 12h, and the expression of AvBD mRNA was measured by real-time PCR. The relative mRNA abundance of 11 AvBDs is summarized in Fig 3. Similar to the observations in other species, 1,25D3 induced the expression of several AvBDs with or without LPS. More specifically, the expression of AvBD3, AvBD6 and AvBD9 was significantly induced by 1,25D3 both in non-stimulated and LPS-stimulated CEIEPCs. Interestingly, the expression of AvBD4 was not up-regulated by 1,25D3 treatment alone, while the combination of LPS and 1,25D3 increased AvBD4 gene expression relative to either treatment alone.

Fig 3. Effects of 1,25D3 on the expression of AvBDs with or without the presence of LPS.

CEIEPCs were treated with 20 ng/mL of 1,25D and 800 μg/mL for 12h. The relative gene expression was measured by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Each bar represents mean ± SD of the results from 2–3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. The bars without the same letter indicate differences significant at P < 0.05.

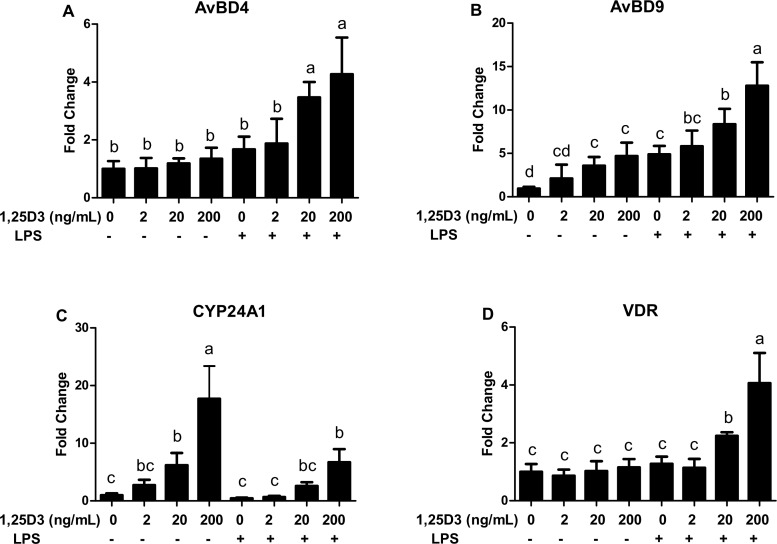

To further investigate the HDP-inducing activity of 1,25D3, CEIEPCs were incubated with increasing concentrations of 1,25D3 with or without LPS stimulation. Expression of AvBD4, AvBD9, vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the positive control gene CYP24A1 mRNA was evaluated by qPCR. Confirming our observations, the expression of AvBD4 was up-regulated by 1,25D3 only in the presence of LPS (Fig 4A). AvBD9 showed a dose-dependent expression in response to both 1,25D3 alone and synergy with LPS (Fig 4B). Moreover, LPS treatment significantly antagonized the expression of CYP24A1 mRNA induced by 1,25D3 (Fig 4C). By contrast, co-treatment of 1,25D3 and LPS showed a synergy role, and notably increased the expression of VDR (Fig 4D).

Fig 4.

The synergy effect of 1,25D3 and LPS on the expression of AvBD4 (A), AvBD9 (B), CYP24A1 (C) and the VDR (D). CEIEPCs were incubated with indicated concentrations of 1,25D3 with or without 800 μg/mL LPS for 12h. Data are shown mean ± SD from 2–3 independent experiments. The bars without the same letter indicate differences significant at P < 0.05.

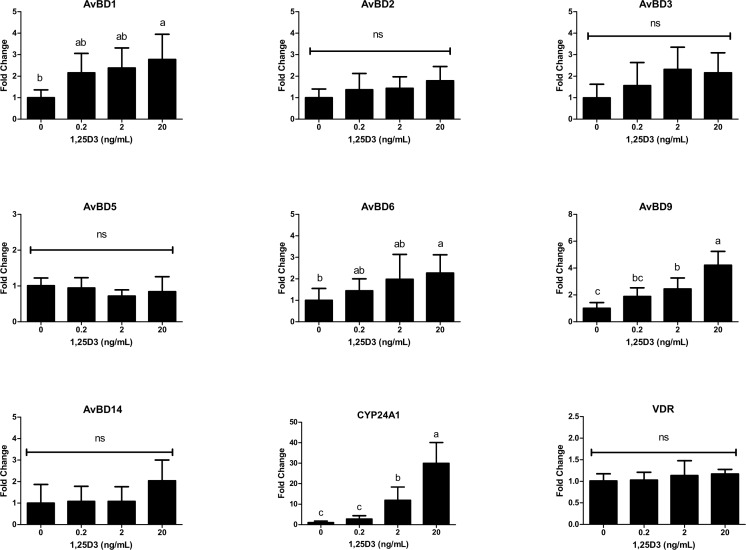

Effect of 1,25D3 on the expression of AvBDs in PBMCs

In mammals, 1,25D3 augmentation of HDPs is widely observed in immunocytes [11, 19, 27]. To investigate the effect of 1,25D3 in monocytes, chicken PBMCs were stimulated with different concentration of 1,25D3 for 24h. In comparison with CEIEPCs, similar results were also observed in PBMCs (Fig 5). Of the seven expressed AvBD genes [12], 1,25D3 significantly increased AvBD6 and AvBD9 expression in PBMCs. AvBD3 was not notably induced in PBMCs at 24h (P > 0.05), instead, AvBD1 was up-regulated about 2.5 fold by 20 ng/mL of 1,25D3 (P < 0.05). At the same time, 1,25D3 increased CYP24A1 expression in a dose-dependent manner suggesting PBMCs are responding to the stimulation of 1,25D3.

Fig 5. Effects of 1,25D3 on the expression of AvBDs in PBMCs.

Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 1,25D3 for 24h. The relative gene expression was measured by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Each bar represents mean ± SD of the results from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The bars without the same letter indicate differences significant at P < 0.05.

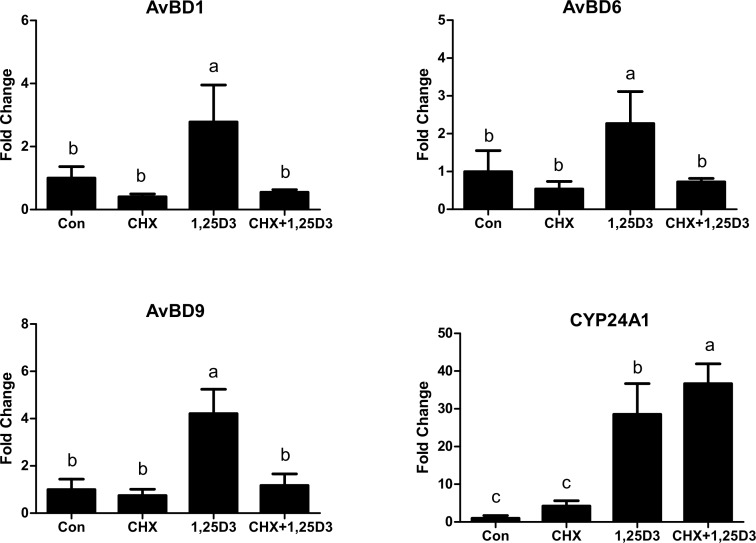

Cycloheximid inhibit 1,25D3 mediated expression of AvBDs

1,25D3 exerts its genomic effects through VDR. After activation by 1,25D3, VDR ligand binds the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to form VDR:RXR heterodimers which can bind to DNA sequences containing vitamin D response elements (VDREs) and influence the transcription of target genes [28, 29]. In humans, VDREs directly regulate the expression of cathelicidin and human β-defensin (HBD) 2, while an intermediate factor is involved in the regulation of β-defensins in cattle [19]. To reveal whether 1,25D3 is able to induce AvBDs expression through VDREs, PBMCs were pre-treated with CHX, the protein translation inhibitor, before 1,25D3 treatment. As shown in Fig 6, CHX completed blocked 1,25D3-induced up-regulation of AvBD1, AvBD6 and AvBD9 in PBMCs. In contrast, CHX did not blunt 1,25D3-induced expression of CYP24A1. Collectively, these results suggest that VDR and putative VDREs are not directly involved in the regulation of AvBDs by 1,25D3. Instead, those AvBDs appear to be secondary 1,25D3 target genes in chicken PBMCs.

Fig 6. AvBDs are not directly regulated by 1,25D3.

Chicken PBMCs were pretreated in duplicate with 10 μg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for 1h, followed by stimulation with 20 ng/mL 1,25D3 for anther 24h. The relative gene expression was measured by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Each bar represents mean ± SD of the results from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The bars without the same letter indicate differences significant at P < 0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we have presented the first evidence that 1,25D3 is capable of inducing the expression of AvBDs in vitro, suggesting that 1,25D3-induced synthesis of HDPs not only occurs in mammals, but is also conserved in chickens. This conclusion is further supported by the fact that 1,25D3 is able to trigger expression of multiple AvBDs in chicken HD11 macrophages (L. Zhang and G. Zhang unpublished data). This evidence indicates that 1,25D3 induction of β-defensins is not specific to mammals. Because all β-defensins emerge from the same ancestor and are conserved across the vertebrate lineage [30, 31], we speculate that 1,25D3-mediated β-defensins are widespread in vertebrates. At the same time, specific expression and regulation patterns of AvBDs were also observed. First, not all of the AvBD members were detectable in CEIEPCs and PBMCs. Among the 14 AvBDs, three and seven of them were not expressed in CEIEPCs and PBMCs, respectively. Secondly, AvBDs were differently regulated by 1,25D3. In CEIEPCs, 1,25D3 alone specifically up-regulated AvBD3, AvBD6 and AvBD9, while AvBD4 was induced only in conjunction with LPS. Finally, AvBDs responded to 1,25D3 in a cell-specific regulation pattern, as indicated by the inability of 1,25D3 to significantly up-regulate AvBD3 and AvBD1 in PBMCs and CEIEPCs, respectively.

In chickens, Vit-D3 and its analogues play an immunomodulatory role in the immune system both in vivo and vitro. In particular, vitamin D-deficiency decreases cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity response to phytohemagglutinin-P [32], while adding extra 25OHD3 to diets enhances both the humoral immune response and cell-mediated immune response [33]. Simultaneously, MQ-NCSU cells treated with 1,25D3 display increased production of nitric oxide and decreased expression of IL-1β as well as chemokine ligand 8 in the presence of LPS [34]. LPS stimulation in HD11 cells concomitantly treated with either 25(OH)D3 or 1,25D3 have higher amounts of IL-10 mRNA [35]. Importantly, a recent study found that maternal supplication of 25D3 enhanced bactericidal capability in posthatch chickens [36]. However, there is no evidence indicating Vit-D3 analogues enhance chicken innate immunity by inducing AvBD expression. Our discovery provides new sight to better understanding the molecular mechanism of Vit-D3 and its metabolic productions in chicken immunity.

Due to the presence of potential VDREs in the promoters of chicken AvBDs [23], we hypothesized 1,25D3 may increase the relative mRNA abundance of some AvBD genes through VDREs. In this experiment, CHX pretreatment completely inhibited 1,25D3-mediated up-regulation of three AvBD genes in PBMCs, however, CHX further increased the expression of CYP24A1, the primary VDR/1,25D3 target gene [28]. These results indicated the induction of AvBD mRNA is not a direct effect of 1,25D3 and other proteins are involved in vitamin D-mediated AvBD response in PBMCs. At present, multiple pathways, proteins and transcription binding motifs have been reported that may contribute to 1,25D3-mediated HDP expression. For example, P38, ERK and JNK signaling pathways are involved in HBD3 expression in keratinocytes [37], while NF-κB signaling pathways are involved in HBD2 expression in primary monocytes [18]. Meanwhile, 1,25D3 treatment increases the levels of Fra1 and c-Fos proteins which enable it to stimulate AP-1 transactivation [37]. In the human THP-1 monocyte cell line, several genes are indirectly induced by 1,25D3 through its regulation of several transcription factors [38]. In chicken macrophages, P3, MAPK, JNK and cAMP signaling regulate the expression AvBD9 [15], suggesting some potential mechanism for further studies. It will be interesting to investigate the mechanisms of 1,25D3-induced chicken HDP expression in the future. On the other hand, because LPS induces the section of pro-inflammatory cytokines and is recognized by several chicken TLRs [39, 40], the mechanism of 1,25D3 in inducing AvBD4 may be similar to HBD2 (also known as DEFB4) expression in human [18], which means that the activation TLRs and cytokines are probably required for the upregulation of AvBD4 in CEIEPCs. Moreover, because both 1,25D3 [41] and LPS [42, 43] are able to alter the histone acetylation which plays a very important role in regulation of HDPs expression [44], we cannot exclude the possibility that histone acetylation is involved in the expression of AvBDs in this study.

The intestinal epithelium is a single-cell layer that generates a physical and biochemical barrier against microorganisms from the external environment. Intestinal epithelial cells secrete various HDPs that not only hinder the growth of microorganisms but also maintain intestinal homeostasis [45–47]. Since intestinal epithelial cells are continually exposed to commensal bacteria and their components, the insensitive of intestinal epithelial cells to LPS is a protective mechanism to avoid eliciting an inflammatory response by the normal external environment [48, 49]. The present results showed that LPS did not significantly trigger the expression of TLR-4 until it reached a concentration of 800 μg/mL. This suggested that CEIEPCs have developed LPS hyporesponsiveness and tolerance to stimulation by bacterial products. Furthermore, oral administration of HDPs is able to enhance barrier functions and suppress inflammatory diseases [50, 51], indicating that strengthening the expression of AvBDs in intestinal cells is probably beneficial to improve the mucosal antimicrobial barrier and reduce the metabolic consequences of the inflammatory response, especially in newborn chickens.

In this study, although 1,25D3 induced the expression of AvBDs, VDR was not regulated by different concentrations of 1,25D3 in both cell types. Instead, the expression of VDR was only induced by 1,25D3 in combination with LPS in CEIEPCs. We speculate it is a cell-type specific response and associated with environmental stimuli. In general, increasing the expression of CYP24A1 could lead to activation of the vitamin D catabolism pathway. Hence, CYP24A1 serves as a feedback regulator to limit the concentration of 1,25D3. In the present study, LPS stimulation inhibited 1,25D3 induced up-regulation of CYP24A1, meaning it blocked the degradation of 1,25D3 and increased the 1,25D3 levels compared to cells without LPS stimulation. This may be the related to the effect of 1,25D3 on VDR and the extra fold change of AvBDs in LPS-activated CIEPCs.

Compared to butyrate that robustly increased HDP expression in chickens, 1,25D3 only produced a marginal effect on the expression of AvBDs. It is important to confirm whether 1,25D3-induced up-regulation of AvBDs is associated with pathogen clearance and disease resistance in the future. In addition, 1,25D3, as well as the vitamin D pathways, are able to interact with other HDP inducers and synergize with specific dietary compounds in HDP induction [13, 52, 53]. For example, in human keratinocytes, butyrate synergizes with 1,25D3 to induce the expression cathelicidin and enhance the antimicrobial function [41]. It is thus important to investigate the synergy effects among different HDP inducers in antibiotic alternatives development.

In conclusion, evidence from the present study demonstrates that 1,25D3 is able to induce the expression of AvBDs in vitro for the first time. Those results indicate that 1,25D3 can be used as an antibiotic alternative to enhance chicken immunity in chickens. However, due to the large phylogenetic distance between chicken and mammals, more investigation is needed to detect the mechanisms and cellular signaling pathways of 1,25D3 in chickens.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of P.R. China (Grants No.31160500), the Young scientists training plan of Jiangxi province (Grant No. 20112BCB23030), the International cooperation plan of Jiangxi province (Grant No. 20111BDH80036) and Foundation of Sichuan Province (2011NZ0099-6).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of P. R. China (Grants No. 31160500), the Young scientists training plan of Jiangxi province (Grant No. 20112BCB23030), the International cooperation plan of Jiangxi province (Grant No. 20111BDH80036) and Foundation of Sichuan Province (2011NZ0099-6).

References

- 1.Zhang G, Sunkara LT. Avian antimicrobial host defense peptides: from biology to therapeutic applications. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;7(3):220–47. 10.3390/ph7030220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock RE, Sahl H-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24(12):1551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai Y, Gallo RL. AMPed up immunity: how antimicrobial peptides have multiple roles in immune defense. Trends in immunology. 2009;30(3):131–41. 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuperus T, Coorens M, van Dijk A, Haagsman HP. Avian host defense peptides. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2013;41(3):352–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynn DJ, Higgs R, Gaines S, Tierney J, James T, Lloyd AT, et al. Bioinformatic discovery and initial characterisation of nine novel antimicrobial peptide genes in the chicken. Immunogenetics. 2004;56(3):170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao Y, Hughes AL, Ando J, Matsuda Y, Cheng J-F, Skinner-Noble D, et al. A genome-wide screen identifies a single β-defensin gene cluster in the chicken: implications for the origin and evolution of mammalian defensins. BMC genomics. 2004;5(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen HK, Levine UY, Looft T, Bandrick M, Casey TA. Treatment, promotion, commotion: antibiotic alternatives in food-producing animals. Trends in microbiology. 2013;21(3):114–9. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall BM, Levy SB. Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2011;24(4):718–33. 10.1128/CMR.00002-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DL, Dushoff J, Morris JG. Agricultural antibiotics and human health. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(8):731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castanon J. History of the use of antibiotic as growth promoters in European poultry feeds. Poultry science. 2007;86(11):2466–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311(5768):1770–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunkara LT, Achanta M, Schreiber NB, Bommineni YR, Dai G, Jiang W, et al. Butyrate enhances disease resistance of chickens by inducing antimicrobial host defense peptide gene expression. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27225 10.1371/journal.pone.0027225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwab M, Reynders V, Loitsch S, Steinhilber D, Schröder O, Stein J. The dietary histone deacetylase inhibitor sulforaphane induces human β‐defensin‐2 in intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology. 2008;125(2):241–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02834.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo C, Rosoha E, Lowry MB, Borregaard N, Gombart AF. Curcumin induces human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide gene expression through a vitamin D receptor-independent pathway. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2013;24(5):754–9. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunkara LT, Zeng X, Curtis AR, Zhang G. Cyclic AMP synergizes with butyrate in promoting β-defensin 9 expression in chickens. Molecular immunology. 2014;57(2):171–80. 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gombart AF. The vitamin D-antimicrobial peptide pathway and its role in protection against infection. Future microbiology. 2009;4(9):1151–65. 10.2217/fmb.09.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones G, Strugnell SA, DeLUCA HF. Current understanding of the molecular actions of vitamin D. Physiological reviews. 1998;78(4):1193–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu PT, Schenk M, Walker VP, Dempsey PW, Kanchanapoomi M, Wheelwright M, et al. Convergence of IL-1beta and VDR activation pathways in human TLR2/1-induced antimicrobial responses. PloS one. 2009;4(6):e5810 10.1371/journal.pone.0005810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merriman KE, Kweh MF, Powell JL, Lippolis JD, Nelson CD. Multiple β-defensin genes are upregulated by the vitamin D pathway in cattle. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2015;154:120–9. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Téllez-Pérez AD, Alva-Murillo N, Ochoa-Zarzosa A, López-Meza JE. Cholecalciferol (vitamin D) differentially regulates antimicrobial peptide expression in bovine mammary epithelial cells: implications during Staphylococcus aureus internalization. Veterinary microbiology. 2012;160(1):91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson C, Reinhardt T, Thacker T, Beitz D, Lippolis J. Modulation of the bovine innate immune response by production of 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D 3 in bovine monocytes. Journal of dairy science. 2010;93(3):1041–9. 10.3168/jds.2009-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang G-W, Li D-B, Lai S-J, Chen S-Y, Lei R-P, Zhou D-G. Effects of dietary vitamin D3 supplementation on AvBD-1 and chCATH-1 genes expression in chicken. The Journal of Poultry Science. 2011;48(4):254–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu L, Li S, Zhang L, Liu X, Li D, Zhao X, et al. Expression of β-defensins in intestines of chickens injected with vitamin D. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2015;14(2):3330–7. 10.4238/2015.April.13.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Ouyang L, Zhou D. Effects of vitamin D3 on expression of defensins, Toll-like receptors, and vitamin D receptor in liver, kidney, and spleen of Silky Fowl. Czech Journal of Animal Science. 2013;58(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Athman R, Fernandez MI, Gounon P, Sansonetti P, Louvard D, Philpott D, et al. Shigella flexneri infection is dependent on villin in the mouse intestine and in primary cultures of intestinal epithelial cells. Cellular microbiology. 2005;7(8):1109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T-T, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, et al. Cutting edge: 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):2909–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haussler MR, Jurutka PW, Mizwicki M, Norman AW. Vitamin D receptor (VDR)-mediated actions of 1α, 25 (OH) 2 vitamin D 3: genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011;25(4):543–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlberg C, Seuter S. The vitamin D receptor. Dermatologic clinics. 2007;25(4):515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu S, Gao B. Evolutionary origin of β-defensins. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2013;39(1):79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittington CM, Papenfuss AT, Bansal P, Torres AM, Wong ES, Deakin JE, et al. Defensins and the convergent evolution of platypus and reptile venom genes. Genome research. 2008;18(6):986–94. 10.1101/gr.7149808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aslam S, Garlich J, Qureshi M. Vitamin D deficiency alters the immune responses of broiler chicks. Poultry Science. 1998;77(6):842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gómez-Verduzco G, Morales-López R, Avila-Gozàlez E. Use of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in Diets of Broiler Chickens: Effects on Growth Performance, Immunity and Bone Calcification. The Journal of Poultry Science. 2013;50(1):60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shojadoost B, Behboudi S, Villanueva A, Brisbin J, Ashkar A, Sharif S. Vitamin D3 modulates the function of chicken macrophages. Research in veterinary science. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris A, Selvaraj RK. In vitro 25-hydroxycholecalciferol treatment of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated chicken macrophages increases nitric oxide production and mRNA of interleukin-1beta and 10. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2014;161(3):265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders-Blades J, Korver D. Effect of hen age and maternal vitamin D source on performance, hatchability, bone mineral density, and progeny in vitro early innate immune function. Poultry science. 2015;94(6):1233–46. 10.3382/ps/pev002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai X, Sayama K, Tohyama M, Shirakata Y, Hanakawa Y, Tokumaru S, et al. PPARγ mediates innate immunity by regulating the 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induced hBD-3 and cathelicidin in human keratinocytes. Journal of dermatological science. 2010;60(3):179–86. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurminen V, Neme A, Ryynänen J, Heikkinen S, Seuter S, Carlberg C. The transcriptional regulator BCL6 participates in the secondary gene regulatory response to vitamin D. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2015;1849(3):300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannaki T, Reddy M, Shanmugam M, Verma P, Sharma R. Chicken Toll-like receptors and their role in immunity. World's Poultry Science Journal. 2010;66(04):727–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kogut M, He H, Kaiser P. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein/CD14/TLR4-dependent recognition of Salmonella LPS induces the functional activation of chicken heterophils and up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine gene expression in these cells. Animal biotechnology. 2005;16(2):165–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schauber J, Oda Y, Büchau AS, Yun Q-C, Steinmeyer A, Zügel U, et al. Histone acetylation in keratinocytes enables control of the expression of cathelicidin and CD14 by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2008;128(4):816–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angrisano T, Pero R, Peluso S, Keller S, Sacchetti S, Bruni CB, et al. LPS-induced IL-8 activation in human intestinal epithelial cells is accompanied by specific histone H3 acetylation and methylation changes. BMC microbiology. 2010;10(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aung HT, Schroder K, Himes SR, Brion K, van Zuylen W, Trieu A, et al. LPS regulates proinflammatory gene expression in macrophages by altering histone deacetylase expression. The FASEB Journal. 2006;20(9):1315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yedery RD, Jerse AE. Augmentation of Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Production with Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as a Novel Epigenetic Therapy for Bacterial Infections. Antibiotics. 2015;4(1):44–61. 10.3390/antibiotics4010044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukherjee S, Hooper LV. Antimicrobial Defense of the Intestine. Immunity. 2015;42(1):28–39. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dupont A, Heinbockel L, Brandenburg K, Hornef MW. Antimicrobial peptides and the enteric mucus layer act in concert to protect the intestinal mucosa. Gut microbes. 2014;5(6):761–5. 10.4161/19490976.2014.972238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2014;14(3):141–53. 10.1038/nri3608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abreu MT, Vora P, Faure E, Thomas LS, Arnold ET, Arditi M. Decreased expression of Toll-like receptor-4 and MD-2 correlates with intestinal epithelial cell protection against dysregulated proinflammatory gene expression in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(3):1609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otte J- M, Cario E, Podolsky DK. Mechanisms of cross hyporesponsiveness to Toll-like receptor bacterial ligands in intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1054–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han F, Zhang H, Xia X, Xiong H, Song D, Zong X, et al. Porcine β-Defensin 2 Attenuates Inflammation and Mucosal Lesions in Dextran Sodium Sulfate–Induced Colitis. The Journal of Immunology. 2015;194(4):1882–93. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang H, Xia X, Han F, Jiang Q, Rong Y, Song D, et al. Cathelicidin-BF, a Novel Antimicrobial Peptide from Bungarus fasciatus, Attenuates Disease in a Dextran Sulfate Sodium Model of Colitis. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2015;12(5):1648–61. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D'Aldebert E, Mve MJBB, Mergey M, Wendum D, Firrincieli D, Coilly A, et al. Bile salts control the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin through nuclear receptors in the human biliary epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1435–43. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwab M, Reynders V, Shastri Y, Loitsch S, Stein J, Schröder O. Role of nuclear hormone receptors in butyrate-mediated up-regulation of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in epithelial colorectal cells. Molecular immunology. 2007;44(8):2107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.