Abstract

The favorable consequences of environmental enrichment (EE) on brain and behavior development are well documented. Much less is known, however, about transgenerational benefits of EE on non-enriched offspring. We explored whether transgenerational effects of EE might extend to the development of repetitive motor behaviors in deer mice. Repetitive motor behaviors are invariant patterns of movement that, across species, can be reduced by EE. We found that EE not only attenuated the development of repetitive behavior in dams, but also in their non-enriched offspring. Moreover, maternal behavior did not seem to mediate the transgenerational effect we found, although repetitive behavior was affected by reproductive experience. These data support a beneficial transgenerational effect of EE on repetitive behavior development and suggest a novel benefit of reproductive experience.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, deer mice, reproductive experience, maternal behavior, early experience

The beneficial effects of environmental enrichment (EE) on behavior and brain development have long been recognized (Hebb, 1949; Greenough, 1975). In humans, EE operationalized as daily exposure to multiple sensorimotor stimuli and motor and cognitive tasks, in various novel combinations, was found to benefit children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Woo and Leon, 2013; Woo et al., 2015). In rodents, larger, more complex rearing environments increased brain weight, dendritic branching and spine densities, synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors, and gene expression (Nithianantharajah and Hannan, 2006). Functionally, such changes are reflected in improved cognitive, affective, and motor performance including attenuation of repetitive behavior and amelioration of deficits associated with modeling neurodegenerative diseases (Hannan, 2014; Lewis, 2004; Nithianantharajah and Hannan, 2006).

A growing body of evidence suggests that EE may benefit the offspring of enriched animals, despite their lack of exposure to EE. Denenberg and Rosenberg (1967) first documented transgenerational effects of early experience in rats, showing weight and activity differences in offspring two generations removed. More recently, Arai and Feig (2009) observed increased long-term potentiation (LTP) not only in mice exposed to EE, but also in their F1 offspring that had never directly experienced EE. Some benefit of EE on LTP also accrued to F2 mice. Transgenerational benefits of EE were associated with a signaling cascade in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and passed on by the mother (Arai and Feig, 2009). Wei et al. (2015) found the EE-induced maternal weight loss resulted in reduced offspring fat accumulation and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, effects associated with altered methylation patterns of metabolic genes in the liver. In rats, transgenerational effects of prenatal maternal EE included improvements in exploration and balance, and reductions in hippocampal DNA methlylation at weaning age (Mychasiuk et al., 2012). Moreover, pre-reproductive maternal EE was effective in improving offspring’s motor and cognitive performance as well as increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Caporali et al., 2014; Cutuli et al., 2015). To our knowledge, there have been no attempts to investigate the transgenerational benefits of EE on the development of repetitive motor behaviors.

Repetitive motor behaviors are most strongly associated with ASD, for which they are diagnostic. However, these repetitive invariant patterns of behavior that seemingly lack function are associated with many neurological, neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., intellectual development disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, tic disorders, fronto-temporal dementias, and schizophrenia) (Lewis and Kim, 2009). Early environmental deprivation (e.g., congenital blindness; orphanages) can also induce repetitive motor behaviors (Fazzi et al., 1999; Rutter et al., 1999). Typically developing children sometimes perform repetitive motor behaviors early in development that wane with age (Thelen 1979; Evans et al., 1997; Kim and Lord, 2010). Repetitive motor behaviors are a prominent feature of animal species maintained in confined conditions (Mason et al., 2007).

Deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) develop high levels of repetitive hind limb jumping and/or backward somersaulting in response to standard laboratory caging (e.g., Muehlmann et al., 2015). EE significantly attenuates the development of repetitive behaviors in deer mice (e.g., Bechard et al., 2016).

The present, exploratory study assessed transgenerational effects of EE on the development of repetitive motor behaviors in deer mice. We hypothesized that EE would reduce the development of repetitive behavior in the parent generation, and that offspring of enriched animals would also develop less repetitive behavior, despite never having directly experienced EE. We also assessed maternal care as a potential mediator of transgenerational effects. Opportunistically, we additionally investigated the effect of a single reproductive experience (in this study, mating, pregnancy, and pup rearing) on the expression of repetitive behavior in the dam. To our knowledge, we are the first to assess the effects of reproductive experience on repetitive behavior expression.

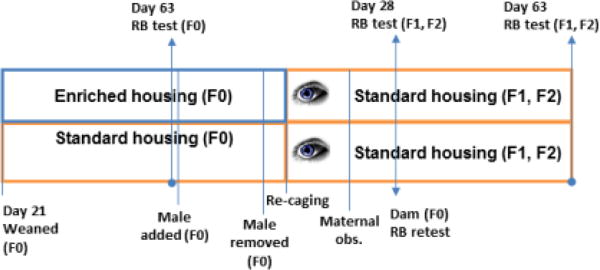

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida and followed the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Our laboratory maintains a colony of deer mice at 70–75°F and 50–70% humidity, under a 16:8 light:dark cycle, from which our parent (F0) generation of deer mice were derived. Figure 1 shows a timeline for the breeding and behavioral assessments. F0 females were weaned at 21 days of age, and siblings split between standard (SH; n=5) and EE (n=10) housing. EE cages were large dog kennels (1.22 × 0.81 × 0.89 m) modified to have three levels interconnected via ramps, with same-sex group sizes of n=4–6. Furnishings inside EE housing consisted of a variety of toys, tunnels and mouse houses, that were systematically rotated each week, and permanent structures that remained undisturbed, such as a large hut and a running wheel. To promote more naturalistic foraging behavior, birdseed was scattered throughout the kennel (~2oz/wk). Nestlets were available for nest construction and refreshed every two weeks, along with food, water, and Sani Chip bedding. Standard environments grouped n=2–3 same-sex individuals within standard rat cages (29 × 18 × 13 cm) provisioned with nestlets, food, water, and bedding, and were refreshed in two week intervals. To control for diet without promoting foraging behaviors, a small amount of birdseed (~0.25oz/wk) was placed in the corner of standard cages at the same time as EE cages.

Figure 1.

A timeline of the breeding and testing schedules.

An age-matched cage of males for standard and EE environments was also generated for the purpose of breeding the subsequent generation. At 65 days of age, one male mouse from the enriched male cage was selected at random and placed into the enriched female cage, and similarly, one standard housed male was placed into the standard female cage. After three weeks, the males were removed and females were moved to individual standard cages to give birth to and rear their F1 offspring.

F1 subjects (EE: n=39, SH: n=21) were born in standard cages, and weaned at 21 days of age into standard cages, grouped by age (+/− 1 day), sex, and housing environment of parents. Following behavioral assessment at 63 days of age, 2 F1 females and 2 F1 males from standard-reared parents, and 3 F1 and 3 F1 males from EE-reared parents were selected for breeding the F2 generation. Pairs remained together for three weeks before males were removed. Unfortunately, 1 EE female lost her pups at birth, and a second EE female lost her pups due to a leaky water bottle that resulted in a flooded cage. In the end, 2 litters of F2 standard pups (n=6) and one litter of F2 EE pups (n=2) were generated. Subjects were left undisturbed in their assigned housing except for routine husbandry procedures. During the rearing of the F1 generation, however, cages were not changed so as to prevent disturbances to maternal behavior. Weight data were collected following the observation session.

Across PND 1–8, instantaneous scan sampling was used to identify dam location and behavior (see Table 1) once every ten minutes, for 1 hour (12:00–1:00pm), resulting in 6 observations per day. We also scored the nest quality of each dam daily (see Table 1). As an additional proxy of maternal investment, dam (F0) and pup (F1) weights were recorded on PND 3, 7, and 21, for a subset of litters.

Table 1.

Description of dam location and behavior.

| Location | Description |

|---|---|

| Dam in nest | Majority of dam positioned inside nest |

| Dam out of nest | Majority of dam positioned outside of nest |

| Behavior | |

| Active | Walking, drinking, eating, grooming |

| Inactive | Sleeping, resting |

| Mothering | Nursing, licking, nosing, grooming, nest building |

| Repetitive behaviors | Pattern of topographically similar behavior performed in bouts (minimum of 3 consecutive events (e.g. hind limb jumps) in less than 3 seconds) |

| Not visible | Cannot see what the dam is doing. No observation made. |

| Nest Score (0–3) | |

| 0 | no nest |

| 1 | 0 < 0.5 cm walls |

| 2 | 0.5–2.0 cm walls |

| 3 | > 2 cm walls/enclosed |

The frequency of repetitive behavior was assessed for each mouse using automated software (Labview software, National Instruments) that records each time there is a break in a photo beam array (Columbus Instruments). The photo beams are positioned high enough so that all four paws of the mouse must leave the floor in order to break them. For each assessment, video surveillance (Geovision software) accompanied the automated data and ensured the accuracy of the automated counts. On the day of testing, mice were placed into individual testing chambers (28 × 22 × 25 cm) at least 30 min prior to lights off (at 10am) until lights on (at 6pm). Food, water, and Sani Chip bedding were provided for the duration of the 8 h assessment period. F0 parent mice were tested for levels of repetitive behavior at 63 days of age and dams were retested 1 week after their offspring were weaned (~2 months after the day 63 assessment). F1 and F2 mice were tested for levels of repetitive behavior at 28 and 63 days of age.

In order to smooth the data for maternal behavior analyses, we calculated the average of behavior over 2 consecutive days (i.e. PND 1 and 2). These binned data values were then used to assess housing conditions on maternal care, which included the proportion of observations spent in contact with the pups, active, inactive, mothering, and performing repetitive behaviors, and nest quality. A Repeated Measures General Linear Model (GLM; SPSS v23) was used to assess differences in maternal care, with rearing environment and age as factors in the model. Differences in litter sizes due to rearing environment were assessed using a GLM with parental (F0) rearing environment as the only factor in the model. This same model was used to assess weight data, which were analyzed separately for each time point (i.e. PND 3) since dam and litter weights were not collected from all litters at every time point.

For each assessment, the total frequency of repetitive behavior across the 8 h test was calculated and used in subsequent analyses. A GLM with housing as a factor in the model was used to assess differences in mean frequencies of repetitive behavior of F0 females exposed to EE. A Repeated Measures GLM was used to assess differences in mean frequencies of repetitive behavior for F1 offspring, using parental (F0) environment, sex and age of the offspring as factors in the model. This same model was used to assess F2 differences in repetitive behavior development. To assess the effects of reproductive experience on repetitive behavior of the dam, a Repeated Measures GLM was used with time (before mothering i.e. d63, and after mothering) and housing as factors in the model.

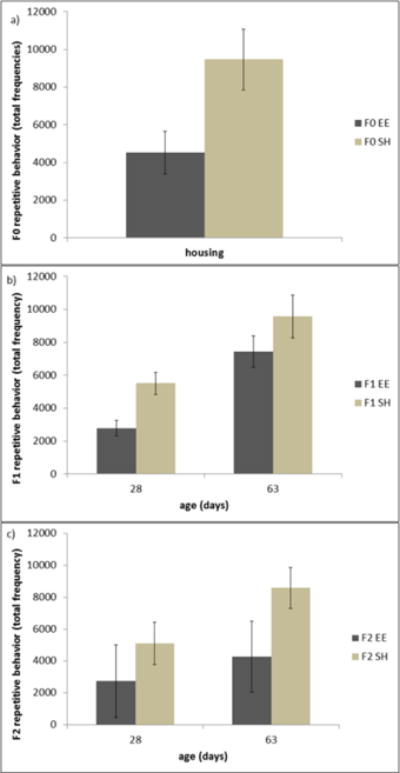

Rearing in EE reduced repetitive behavior development (F(1,13)=6.3, p=0.026; Fig. 2a). Rearing environment had no significant effects on maternal care, as indicated by maternal contact, behaviors, and nest provisioning (all p>0.05). Across PND 1–8, we found non-significant trends for dams from both rearing conditions to spend less time in the nest with their pups (F(3,39)=2.38, p=0.084) and more time active (F(3,39)=2.85, p=0.05). There were no differences in mean litter size (EE: 3.3 pups vs SH: 3.6 pups), and nor were there differences in dam or offspring weights at any time point (all p>0.05).

Figure 2.

The mean total frequencies of repetitive motor behaviors for a) F0 females reared in environmental enrichment (EE) and standard housing (SH), b) non-enriched F1 offspring, and c) non-enriched F2 offspring. Data bar shows mean ± SEM.

The F1 offspring of EE parents developed significantly less repetitive behavior compared to F1 offspring of SH parents (F(1,56)=5.03, p=0.029; see Fig. 2b). For all F1 offspring, repetitive motor behaviors increased with age (F(1,56)=39.2, p<0.001). Although the F2 offspring of EE parents displayed lower mean frequencies of repetitive behavior than F2 offspring of SH parents, differences failed to meet the level of significance (F(1,6)=2.26, p=0.18; see Fig. 2c).

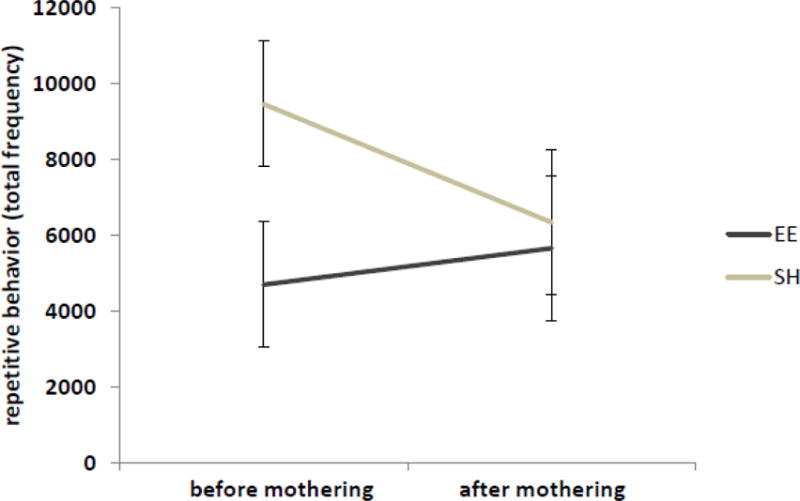

The effect of reproductive experience on repetitive behavior development of the dams was dependent on rearing condition (F(1,12)=7.17, p=0.02; see Fig. 3). Rearing in standard housing generated adults with increased levels of repetitive behavior that were reduced following reproductive experience. Rearing in EE housing generated adults with reduced levels of repetitive behavior that did not change following reproductive experience.

Figure 3.

The effect of reproductive experience on repetitive motor behaviors. Data point shows mean ± SEM.

Using a mouse model, we found a beneficial transgenerational effect of EE on the development of repetitive behavior in offspring never having experienced EE. F1 offspring of EE reared parents developed fewer repetitive motor behaviors than F1 offspring of standard reared parents. Although not statistically significant, the development of repetitive behavior in F2 offspring was similar to that of F1 mice: EE F2 mice displayed less repetitive behavior both in early adolescence and adulthood than standard F2 mice. The small number of F2 EE pups limited the strength of this comparison, however. Both direct and indirect measurements of maternal care suggested that this effect was not maternally mediated, as EE and standard reared dams demonstrated no differences in maternal investment across PND 1–8. We believe this assessment for differences in maternal behaviors of the F0 generation strengthens the findings, having directly tested one potential mechanism for mediating beneficial effects of parental environment on repetitive behavior development.

Evidence from both human and animal studies in support of transgenerational inheritance has been growing. Environmental factors such as stress, diet and toxins have been shown to influence transgenerational inheritance relevant to neurobiological disease, including depression, anxiety, addiction, and ASD (Roth et al., 2009; Vassoler and Sadri-Vakili, 2013; Saab and Mansuy, 2014). Fewer studies have investigated the transgenerational effects of enriching environments on behavior. Of those studies that have, positive effects for offspring, such as enhanced plasticity and memory (Arai and Feig, 2009; Cutuli et al., 2015), motor coordination and balance (Caporali et al., 2014; Mychasiuk et al., 2012), and metabolic health (Wei et al., 2015), were found.

The novel transgenerational effect of EE to reduce repetitive behavior development in non-enriched offspring was, we believe, not maternally-mediated. Although the F2 results need to be replicated these pilot data are promising, suggesting that transmission of the phenotype will persist across several generations and derive from an epigenetic mechanism. Future studies are needed to establish if there are associated changes in the epigenome by which they are mediated.

In addition, we demonstrated that a single reproductive experience affected repetitive behavior levels, although this was dependent on rearing environment. Reproductive experience for standard reared females had a beneficial effect and reduced levels of repetitive motor behaviors. We thus suggest that reproductive experience may be a special case of environmental enrichment. Other studies support this with beneficial findings of reproductive experience on dam anxiety, cognition, affect, stress response, and neural function (Macbeth and Luine, 2009). For EE reared females, however, reproductive experience did not alter levels of repetitive motor behavior. Potentially, its ameliorating effect in EE females was masked by degradation of environmental complexity associated with being moved into standard cages. Notwithstanding, these data are some of the first to empirically support the beneficial effects of reproductive experience on repetitive behavior.

In summary, novel findings from this exploratory study support a beneficial influence of the parental environment on offspring development of repetitive behavior. Moreover, maternal behavior did not seem to mediate the transgenerational effect, although repetitive behavior was affected by reproductive experience. The transgenerational effect of EE on repetitive behavior development now requires replication and the identification of epigenetic mechanisms mediating this effect.

Highlights.

EE reduced repetitive motor behaviors of dams and their non-enriched offspring

Maternal care did not differ between EE and standard reared dams

Reproductive experience reduced repetitive motor behaviors in non-enriched dams

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant MH0800055.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arai JA, Li S, Hartley DM, Feig LA. Transgenerational rescue of a genetic defect in long-term potentiation and memory formation by juvenile enrichment. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1496–1502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard AR, Cacodcar N, King MA, Lewis MH. How does environmental enrichment reduce repetitive motor behaviors? Neuronal activation and dendritic morphology in the indirect basal ganglia pathway of a mouse model. Behav Brain Res. 2016;299:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporali P, Cutuli D, Gelfo F, Laricchiuta D, Foti F, De Bartolo P, Mancini L, Angelucci F, Petrosini L. Pre-reproductive maternal enrichment influences offspring developmental trajectories: motor behavior and neurotrophin expression, Front. Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:195. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutuli D, Caporali P, Gelfo F, Angelucci F, Laricchiuta D, Foti F, Bartolo PDe, Bisicchia E, Molinari M, Vecchioli SFarioli, Petrosini L. Pre-reproductive maternal enrichment influences rat maternal care and offspring developmental trajectories: behavioral performances and neuroplasticity correlates, Front. Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:66. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH, Rosenberg KM. Nongenetic transmission of information. Nature. 1967;216:549. doi: 10.1038/216549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, Leckman JF, Carter A, Reznick JS, Henshaw D, King RA, Pauls D. Ritual, habit, and perfectionism: The prevalence and development of compulsive-like behavior in normal young children. Child Dev. 1997;68:58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzi E, Lanners J, Danova S, Ferrarri-Ginevra O, Gheza C, Luparia A, Balottin U, Lanzi G. Stereotyped behaviours in blind children. Brain Dev. 1999;21:522–528. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT. Experiential modification of the developing brain. Am Sci. 1975;63:37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan AJ. Environmental enrichment and brain repair: harnessing the therapeutic effects of cognitive stimulation and physical activity to enhance experience-dependent plasticity. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40:13–25. doi: 10.1111/nan.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. The organization of behavior. Psychology Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Lord C. Restricted and repetitive behaviors in toddlers and preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Autism Res. 2010;3:162–173. doi: 10.1002/aur.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH. Environmental complexity and central nervous system development and function. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:91–95. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Kim SJ. The pathophysiology of restricted repetitive behavior. J Neurodev Disord. 2009;1:114–132. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macbeth AH, Luine VL. Changes in anxiety and cognition due to reproductive experience: A review of data from rodent and human mothers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:452–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason G, Clubb R, Latham N, Vickery S. Why and how should we use environmental enrichment to tackle stereotypic behaviour? Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007;102:163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlmann AM, Bliznyuk N, Duerr I, Lewis MH. Repetitive motor behavior: further characterization of development and temporal dynamics. Dev Psychobiol. 2015;57:201–211. doi: 10.1002/dev.21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mychasiuk R, Zahir S, Schmold N, Ilnytskyy S, Kovalchuk O, Gibb R. Parental enrichment and offspring development: modifications to brain, behavior and the epigenome. Behav Brain Res. 2012;228:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithianantharajah J, Hannan AJ. Enriched environments, experience-dependent plasticity and disorders of the nervous system. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:697–709. doi: 10.1038/nrn1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting Epigenetic Influence of Early-Life Adversity on the BDNF Gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Andersen-Wood L, Beckett C, Bredenkamp D, Castle J, Groothues C, Kreppner J, Keaveney L, Lord C, O’Connor TG, T. English Romanian Adoptees Study Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation. J Child Psychol Psyc. 1999;40:537–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab BJ, Mansuy IM. Neurobiological disease etiology and inheritance: an epigenetic perspective. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:94–101. doi: 10.1242/jeb.089995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E. Rhythmical stereotypies in normal human infants. Anim Behav. 1979;27:699–715. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(79)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Yang CR, Wei YP, Ge ZJ, Zhao ZA, Zhang B, Hou Y, Schatten H, Sun QY. Enriched environment-induced maternal weight loss reprograms metabolic gene expression in mouse offspring. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4604–4619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CC, Donnelly JH, Steinberg-Epstein R, Leon M. Environmental enrichment as a therapy for autism: A clinical trial replication and extension. Behav Neurosci. 2015;129:412–422. doi: 10.1037/bne0000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CC, Leon M. Environmental enrichment as an effective treatment for autism: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Neurosci. 2013;127:487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0033010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]