Abstract

Previous literature reveals a high prevalence of grief in dementia caregivers before physical death of the person with dementia that is associated with stress, burden, and depression. To date, theoretical models and therapeutic interventions with grief in caregivers have not adequately considered the grief process, but instead have focused on grief as a symptom that manifests within the process of caregiving. The Dementia Grief Model explicates the unique process of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers. In this paper we introduce the Dementia Grief Model, describe the unique characteristics dementia grief, and present the psychological states associated with the process of dementia grief. The model explicates an iterative grief process involving three states – separation, liminality, and re-emergence – each with a dynamic mechanism that facilitates or hinders movement through the dementia grief process. Finally, we offer potential applied research questions informed by the model.

Keywords: ambiguous loss, caregiving, dementia grief, pre-death grief

There are 5.4 million people in the United States with Alzheimer's disease and approximately 15 million unpaid, informal family caregivers attending to them, incurring costs estimated to total $214 billion in 2014 (Alzheimer's Association, 2014). Dementia caregivers, especially spouses, are at increased risk for developing mental and physical health conditions related to the stress of caregiving (Kiely, Prigerson, & Mitchell, 2008). Caregivers experience a magnitude of stress in dementia caregiving preceding physical death considered equal to or greater than the stress in bereavement after physical death (Noyes et al., 2010). Caregivers who experience higher levels of pre-death grief have a higher risk of health complications post-death (Chan, Livingston, Jones, & Sampson, 2013; Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Schaffer, & Mitchell, 2011; Sanders, Ott, Kelber, & Noonan, 2008; Shuter, Beattie, & Edwards, 2013). Dementia researchers have focused on describing and defining pre-death grief (Lindauer & Harvath, 2014; Meuser & Marwit, 2001; Sanders & Corely, 2003) and exploring the association between grief, stress, and depression in caregivers (Adams & Sanders, 2004; Chan et al., 2013; Holly & Mast, 2009; Noyes et al., 2010). To date, pre-death grief in dementia is predominantly understood within the stress-process model of caregiving (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) where grief emerges as symptoms within an overarching stress process (Noyes et al., 2010). We propose that the dementia grief process, which is normative within the context of caregiving, is at risk of being impeded due to aspects unique to dementia. In this paper we present a theoretical model of dementia grief by placing the caregiving experience within an a grief framework to clarify how the disease process makes grief distinct by presenting specific hindrances to its natural trajectory, posing risks to caregiver health by increasing pre-death grief levels that can impact levels of stress and depression.

Literature Review

Pre- and Post-Death Grief

Grief is generally understood to be the psychological response to a disruption in a significant attachment through death or loss (Bowlby, 1973, 1969; Mancini, Robinaugh, Shear, & Bonanno, 2009; Neimeyer, Prigerson, & Davies, 2002; Shear, 2010; Stroebe, Schut, & Boerner, 2010). Caregivers show a high prevalence of stress, grief, and depression before the physical death of the person with dementia (Adams & Sanders, 2004; Joling et al., 2012; Meuser & Marwit, 2001; Ott, Kelber, & Blaylock, 2010; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2004), yet rarely recognize symptoms of pre-death grief (Marwit & Meuser, 2001; Sanders & Corley, 2003; Silverberg, 2007). Pre-death grief increases as dementia advances (Adams & Sanders, 2004; Chan et al., 2013; Meuser & Marwit, 2001; Ott et al., 2010;), as caregiver health deteriorates (Holley & Mast, 2007), and as a sense of burden increases (Chan et al., 2013; Holley & Mast, 2009). Grief increases as caregivers plan for and make facility placement (Chan et al., 2013; Marwit & Meuser, 2001; Walker & Pomeroy, 1996), while burden and depression decrease after facility placement (Gaugler, Mittelman, Hepburn, & Newcomer, 2014).

There is an emerging association between degrees of pre-death grief and post-death complicated grief in dementia caregivers. Complicated grief can occur as a result of any loss and is defined as a prolonged and severe form of grief that includes separation distress, intrusive thoughts, and an inability to resolve the loss (Shear, 2010). Complicated grief occurs in approximately 20% of dementia caregivers following physical death of the person with dementia (Holland, Currier, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2009; Schulz et al., 2006), and 30% are at risk of clinical depression in the first year (Schulz et al., 2006). Greater pre-death grief is a key predictor of post-death complicated grief in dementia caregivers (Holland et al., 2009; Schulz et al., 2006). Interventions that reduce levels of burden and stress in dementia caregivers decrease levels of post-death depression and complicated grief (Hebert et al., 2006; Schulz et al., 2006).

The purpose of this paper is to present the Dementia Grief Model, a theoretical model of dementia grief as a unique grief experience in dementia caregivers. First we define the term dementia grief. Then, we present a review of research and theories that inform the Dementia Grief model. In the model, the trajectory of dementia grief iteratively cycles through three psychological states: separation, liminality, and re-emergence. Distinguishing characteristics of each respective state is discussed, including compounded loss, ambiguity, and adaptation. Finally, potential implications of the Dementia Grief model are discussed with respect to clinical interventions and research.

Dementia Grief

Pre-death grief in dementia family caregivers, or dementia grief, captures the unique role the disease process plays while implying pre-death status, as the grief response to physical death is readily termed bereavement (Chan et al., 2013; Lindauer & Harvath, 2014). Dementia grief is a specific type of anticipatory grief in response to compounded serial losses of varying magnitude and marked by the ambiguity that characterize the experiences of loss in dementia.

Lindauer and Harvath (2014) offer the following definition of pre-death grief in dementia family members:

Pre-death grief in the context of dementia family caregiving is the caregiver's emotional and physical response to the perceived losses in a valued care recipient. Family caregivers experience a variety of emotions … that can wax and wane over the course of a dementing disease, from diagnosis to the end of life. (p. 8)

Dementia grief overlaps with anticipatory grief (Chan et al., 2013; Large & Slinger, 2013; Lindauer & Harvath, 2014). Anticipatory grief may occur in many terminal medical conditions (Chan et al., 2013; Large & Slinger, 2013). Dementia grief is distinguished from anticipatory grief by disruptions in communication and impairments in awareness that occur even early on in the disease. With most terminal medical conditions, there is an opportunity for conflict resolution and sharing feelings between the dying person and their family members up until death (Lindauer & Harvath, 2014; Rando, 2000). However, the opportunity for similar resolution is limited for dementia caregivers due to language deficits and a lack of insight in care recipients resulting from disruptions in reasoning that can manifest in the early stages of dementia (Noyes et al., 2010; Santulli & Blandin, 2015).

Dementia Grief: Compounded Loss, Ambiguity, and Receding of the Known Self

Compounded serial loss

Most significant losses associated with dementia occur before physical death. A key experience in dementia grief is of compounded serial losses (Chan et al. 2013; Large & Slinger, 2013; Santulli & Blandin, 2015). Compounded serial losses build in number and magnitude as the disease progresses. Early losses include memory and communication deficits as well as withdrawal from activities. Advanced losses include declines in ability to cook, drive, and dress (Mace & Rabins, 2006; Mittelman, Epstein, & Pierzchala, 2003; Santulli, 2011). Compounded serial losses are numerous and cyclical in nature; family members experience many small losses and several large losses during the extended trajectory of the disease process (Mace & Rabins, 2006; Mittelman et al., 2003; Santulli, 2011; Santulli & Blandin, 2015).

Ambiguity

Dementia grief is characterized by ambiguous loss. Ambiguous loss (Boss 1999; Boss 2002; Boss 2011) is experienced as a lack of clarity due to losses that are unstable and fluctuating, evading finality and resolution. In dementia, ambiguity derives from the manner of losses that fluctuate through the disease trajectory, as well as types of losses. For example, some family members may experience a loss of hope for reconciliation of past conflicts with the person with dementia, while others may experience loss of an envisioned future and expectations (Chan et al., 2013; Noyes et al., 2010; Sanders & Corely, 2003; Santulli & Blandin, 2015). These types of losses are more typically experienced when a person has physically died, and their presence when the person with dementia is physically alive is particularly confounding.

Ambiguity also emerges from increasingly profound changes in cognition and states of consciousness in the person with dementia. Of note, losses of identifying personality characteristics and the ability to access personal memories lead to experiences of ambiguity in family members in that the person with dementia may not appear to be the same person or may be psychologically inaccessible (Chan et al., 2013; Dupuis, 2002; Frank, 2008; Noyes et al., 2010; Ott et al., 2010; Sanders & Corely, 2003). Ambiguous loss is rarely recognized by family members themselves or others. A lack of acknowledgement and the unpredictable timing of losses exacerbate the ambiguity in dementia caregiving (Sanders & Corley, 2003; Shuter et al., 2013). The lack of clarity and resolution from ambiguous loss may be prolonged for years, as the median span of caregiving for a loved one with dementia is 5 to 8 years (Xie, Brayne, & Matthews, 2008). Due to this protracted state, it can be especially challenging to process difficult feelings related to loss, grief, and burden because a final resolution of grief cannot typically occur until physical death (Boss, 1999, 2011; Furlini, 2001; Large & Slinger, 2013; Sanders & Corely, 2003).

Receding of the Known Self

A significant distinguishing factor of dementia grief is particular psychological losses of the person with dementia that occur before physical death. We offer the term the receding of the known self. Receding of the known self is defined as the changes in the self, including identifying personality characteristics, memories, and abilities, observed in people with dementia. Lindauer and Harvath (2014) found that dementia grief in caregivers is primarily a response to the psychological loss of the person the family has known and experiencing this loss slowly over time is particularly stressful (Albinsson & Strang, 2003; Lindauer & Harvath, 2014; Sanders et al., 2008; Sanders & Corley, 2003).

A common experience among family members is that eventually the person with dementia will express themselves as though they are someone else, someone new, or otherwise not who they used to be (Albinsson & Strang, 2003; Chan et al., 2013; Madsen & Birkelun, 2013). Family members experience profound pre-death grief akin to post-death bereavement as they experience the loss of the person they know (Meuser, Marwit, & Sanders, 2004; Sanders et al., 2008). Yet their loved one is still alive, and though they may not act like the same person caregivers once knew, they are the same person and family members often strive to remain connected to them (Large & Slinger, 2013; Lindauer & Harvath, 2014). An adult daughter spoke to directly to this ambiguity when she stated that her mother died for her the day her mother didn't recognize her anymore (Madsen & Birkelun, 2013). This creates a paradoxical disconnection between the physical and psychological losses, capturing the crux of ambiguity in the receding of the known self in dementia grief.

The Grief Process

Grief is fluid

The current paradigm, that some term the “new science” of grief, asserts that grief is a fluid and dynamic process that will naturally resolve itself for most bereaved people (Bonnano, 2009; Konisberg, 2011). The consensus among grief theorists and researchers is that grief is a cyclical processing of emotions that over time resolves painful feelings of loss into acceptance and adaptation (Farran, Keane-Hagerty, Salloway, Kupferer, & Wilken, 1991; Maciejewski et al., 2007; Neimeyer et al., 2002; Neimeyer, 2006; Prigerson & Maciejewski, 2008; Romanoff & Terenzio, 1998). Further, research has clarified the distinction between normal and pathological forms of grief. While most grief naturally resolves and does not need to be treated (Bonanno, 2004; Bonanno & Mancini, 2008), a small but stable minority of bereaved people develops complicated or chronic forms of grief, requiring identification and treatment (Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005).

The Dual Process Model of Coping in Bereavement (DPMCB) represents a current understanding of the dynamic and iterative trajectory of grief (Richardson, 2007, 2010; Stroebe & Schut, 1999). The DPMCB frames the process of bereavement in the oscillation between two orientations: a loss-oriented adaptation and restoration-oriented adaptation. Loss-oriented adaptations involve coping directly with the deceased person while restoration-oriented adaptations focus on secondary stressors resulting from the loss (e.g., financial responsibilities, role changes). The bereaved move naturally between confronting losses and avoiding the reality of losses as well as confronting and avoiding restoration needs as their grief resolves (Richardson, 2007; Stroebe & Schut, 1999; Stroebe et al., 2010). In an analysis of interviews with family members of a person with dementia, Madsen and Birkelund (2013) noted congruence between the reported experiences of grief in the family members and the loss-restoration patterns described by the DPMCB.

Existing Dementia Grief Models

While several conceptual models of the general grief and bereavement process have been offered to the field, to our knowledge three models specifically addressing dementia grief have been offered to date by Noyes and colleagues (2010), Marwit and Meuser (2001, 2002), and Silverberg (2007). Noyes and colleagues' (2010) model places grief symptoms within an expanded stress process model of dementia caregiving. Meuser and Marwit's (2001) model contrasts descriptions and intensity of grief experiences in caregivers correlated with the stages of dementia in the care recipient (Marwit & Meuser, 2002). Silverberg's (2007) 3-A grief intervention model offers a three-pronged intervention of acknowledging grief, assessing coping styles, and assisting caregivers with managing grief symptoms. Each of these models characterizes grief as a symptom among many of the dementia caregiving experience. While not naming grief specifically, other models deal with the nuanced losses in caregiving (Pearlin et al., 1990).

In contrast, the Dementia Grief model brings attention and focus to the overarching grief process associated with dementia, rather than only recognizing grief as a discrete symptom. Further, the Dementia Grief model characterizes dementia grief as a normal grief process and experience with unique properties. The Dementia Grief Model is predicated upon the distinct characteristics of dementia grief and identifies mechanisms unique to the dementia grief process that facilitate and/or hinder caregivers in moving through repetitive patterns of loss. The model can be applied to provide understanding of how grief impacts caregiver burden and stress. Understanding these mechanisms can lead to potentially new and effective interventions with dementia caregivers.

The Dementia Grief Model

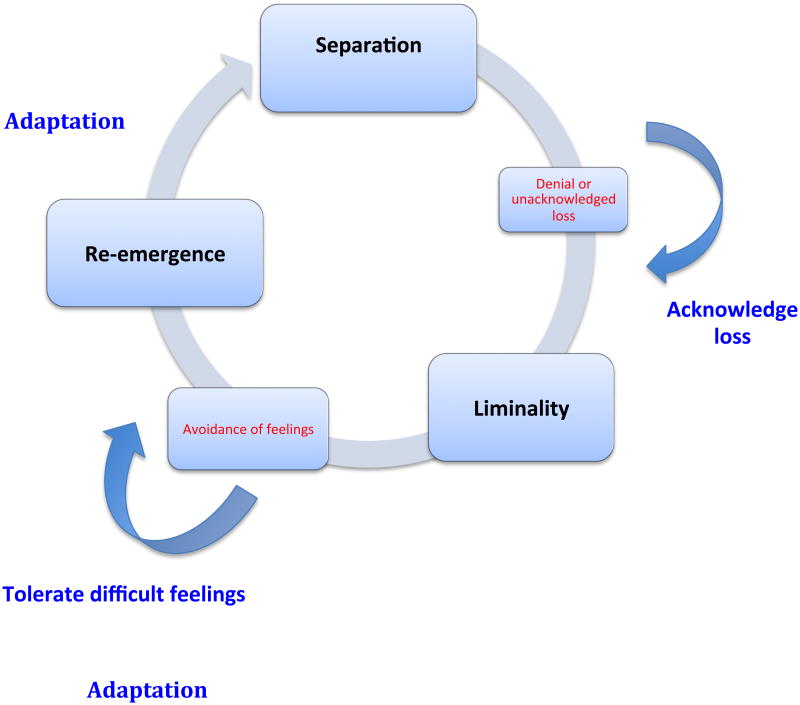

In the Dementia Grief model, grief cycles through three states: separation, liminal, and re-emergence. See Figure 1 for details. Each state is characterized by a specific psychological state and has a dynamic mechanism that propels movement through the grief process. Failure of the dynamic mechanism is hypothesized to inhibit the grief trajectory, adding to the distress of the caregiver. We propose that the dementia grief process is vulnerable to being stalled through a failure of the dynamic mechanisms: acknowledging loss, tolerating difficult feelings, and adapting to the new life circumstance or reality of the loss. The dynamic mechanisms provide a specific focus for future interventions.

Figure 1. Dementia grief states and dynamic mechanisms.

State of Separation

A person is in a state of separation when they suffer a significant loss(es). Separation is characterized by compounded serial losses; the dynamic mechanism is acknowledgment of loss. Each loss invites a state of separation from the person with dementia, from the life one has lived in the past, and from an anticipated future. Acknowledging that a significant loss has occurred is an initial recognition of the grief process, which, as noted above, caregivers do not always recognize (Marwit & Meuser, 2001; Sanders & Corley, 2003; Silverberg, 2007).

The dynamic mechanism of acknowledgment can be inhibited through a lack of recognizing losses, resistance or denial of the losses, or an inability to emotionally acknowledge losses. Achieving resolution of compounded loss can be challenging because they are either irresolvable or come at such a rate that there is not enough time or energy available to devote to the consequences of each loss. For example, a slow receding of the known self occurring in the years before physical death is difficult to resolve, putting a caregiver at risk of stalling in separation, unable or unwilling to acknowledge loss. Similarly, a caregiver is at risk of stalling in separation if facing multiple, compounded losses without adequate time to fully recognize each loss and their associated consequences, as when the person with dementia is no longer able to manage finances, to be left alone, and loses the ability to drive all within a span of a few months.

The Liminal State

Liminality is the state of being in-between a previous situation and an emerging situation. The liminal state is characterized by ambiguity and has a dynamic mechanism of tolerating difficult feelings. Liminal derives from the Latin word limen, which means threshold. In crossing a threshold, there is movement from one place or state to another; when one stands in the threshold, however, one is betwixt and between both. Liminality is an apt description of an experience of ambiguous loss (Boss, 2011) and thus the liminal state is linked with ambiguity and the receding of the known self, preceding physical death. Liminality is a state of transition, and while the end result may be positive, the process is ambiguous and unstable.

The dynamic mechanism of tolerating difficult emotions can be hindered if painful feelings are avoided or otherwise suppressed. Consequences of this avoidance can manifest in unhealthy habitual behaviors, such as indulging in food or alcohol, or in compulsive behaviors, such as angry outbursts or chronic distracting activities. Tolerating painful emotions enables the grief process to unfold into clarity of the caregiver's losses and the possibility of adaptation to the new, emergent situation. This clarity moves them naturally into states of re-emergence in which recognition of a new landscape, inner and outer, enables adaptation to the consequences of their losses.

The State of Re-emergence

The state of re-emergence is characterized by acceptance and the dynamic mechanism is adaptation. Tolerating and confronting difficult emotions in the liminal state eventually unfold into states of clarity wherein the losses one has experienced are acknowledged, accepted, and understood in their consequences. Adaptation is enacted in behavior, such as arranging for new circumstances in care, taking over a responsibility previously held by the person with dementia, or learning to communicate with the care recipient in a new way. Re-emergence can appear on a specific loss (intimacy, anticipated future, freedom, etc.), or, it can appear as a state of clarity and grounding that one is moving through stages of the disease (realizing one has moved from the early to the moderate stage of Alzheimer's disease due to an important functional loss, such as a crisis with driving). Adaptation signals a resolution of loss in a practical manner, i.e., the loss has been recognized, accepted, and the new reality has been incorporated into daily life. This brings a sense of finality, albeit temporary. Adaptation is a crucial step for the caregiver in providing an aspect of closure and stability.

Conclusion

The Dementia Grief model offers a theoretical model of dementia grief to better understand the unique characteristics of dementia grief and the process of dementia caregiving by placing the caregiving experience within an overarching context of grief. In the model, grief cycles through three states: separation, liminal, and re-emergence. Each state has a dynamic mechanism that propels movement through the grief process; failure of the dynamic mechanism is hypothesized to inhibit the grief trajectory, adding to the emotional stress of the caregiver. Acknowledging loss is the dynamic mechanism in separation that moves one into a liminal state of being confronted with ambiguity and difficult feelings. The dynamic mechanism of tolerating difficult or negative emotions in the liminal state allows the caregiver's experience to naturally clarify into a state of re-emergence in which they can make behavioral adaptations to a new reality. Re-emergence is accomplished through the dynamic mechanism of adaptation to the new life situation, i.e., adapting to the reality of the loss. Adaptation is the goal of grief generally that signals resolution; in the case of dementia grief, it is a temporary finality as the cycle is enacted repeatedly until physical death.

This new framework provides opportunity for innovative therapeutic interventions through the dynamic mechanisms of acknowledging loss in separation, tolerating difficult feelings in liminality, and in behavioral adaptations in re-emergence. Though this is a descriptive theoretical model, it potentially informs testable research questions on the process of grief and the development of targeted interventions including:

How are the dynamic mechanisms represented in caregiver decisions?

To what extent does the dementia grief process impact the quality and effectiveness of caregiver decisions?

How do the adaptive modes of primary and secondary control predict health outcomes in dementia caregivers?

To what extent does intervention in the dementia grief process impact levels of depression, stress and burden in pre-death caregiving?

To what extent does intervention in the dementia grief process impact post-death depression and/or complicated grief?

How do individual differences (i.e., personality, attachment styles) facilitate or inhibit the dynamic mechanisms?

Dementia caregiving involves changing emotional states in response to radical losses and changing conditions as the disease progresses in the person with dementia. By viewing dementia caregiving and dementia grief in an overarching frame of grief in general, we can identify specific mechanisms for moving through patterns of loss over time. The Dementia Grief model highlights these patterns particular to the unique experience of grief in dementia caregivers. Strengthened abilities of caregivers to cope with the stressors of dementia caregiving by gaining competency in managing the grief process may lead to better health outcomes during caregiving as well as after physical death of the person with dementia.

Footnotes

The final, definitive version of this article is available at http://online.sagepub.com/

References

- Adams KB, Sanders S. Alzheimer's caregiver differences in experience of loss, grief reactions and depressive symptoms across stage of disease: A mixed-method analysis. Dementia. 2004;3(2):195–210. doi: 10.1177/1471301204042337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albinsson L, Strang P. Existential concerns of families of late-stage dementia patients: Questions of freedom, choices, isolation, death and meaning. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6(2):225–235. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2014 Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2014;10(2):e47–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen P, Schut H, Stroebe M, Zijerveld A. Continuing bonds and grief: A prospective analysis. Death Studies. 2006;30:767–776. doi: 10.1080/07481180600852936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Heckhausen J. To have and have not: Adaptive bereavement by transforming mental ties to the deceased. Death Studies. 2003;27:199–226. doi: 10.1080/07481180302888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Schulz R. Caregiving, bereavement, and complicated grief. Bereavement Care. 2009;28(3):10–13. doi: 10.1080/02682620903355382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After Loss. NY: Perseus Books Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Mancini AD. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):369–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, et al. Nesse RM. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18 months postloss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(5):1150–1164. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Nesse RM. Prospective Patterns of Resilience and Maladustment During Widowhood. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):260–271. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss P. Loving Someone Who Has Dementia: How to Find Hope While Coping with Stress and Grief. NY: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boss P. Ambiguous loss in families of the missing. The Lancet. 2002;360:s39–s40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11815-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss P. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, volume 1: Attachment. NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, volume 2: Separation. NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chan D, Livingston G, Jones L, Sampson EL. Grief reactions in dementia carers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28:1–17. doi: 10.1002/gps.3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore J, Flint M. Mediating grief: Postmortem ritualization after child death. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2012;17:158–172. doi: 10.1080/15325024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore J, DeFrain J, Jones KLC. When a baby dies: Ambiguity and stillbirth. Marriage and Family Review. 2008;44(4):439–454. doi: 10.1080/01494920802454017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doka K. Living with grief: Alzheimer's disease. Washington, DC; Hospice Foundation of America; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis SL. Understanding ambiguous loss in the context of dementia care: Adult children's perspectives. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2002;37(2):93–115. doi: 10.1300/J083v37n02_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farran CJ, Keane-Hagerty E, Salloway S, Kupferer S, Wilken CS. Finding meaning: An alternative paradigm for Alzheimer's disease family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 1991;31(4):483–489. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JB. Evidence for grief as the major barrier faced by Alzheimer caregivers: A qualitative analysis. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias. 2008;22(6):516–527. doi: 10.1177/1533317507307787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JL, Linde BD, Gigliotti C, Kim KY. Grief experiences of 3 caregiving wives of veterans with dementia. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. 2012;30(2):137–145. doi: 10.1177/1049909112446847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlini L. The parent they knew and the ‘new’ parent: Daughters' perceptions of dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2001;20(1):21–38. doi: 10.1300/J027v20n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Mittelman MS, Hepburn K, Newcomer R. Identifying at-risk dementia caregivers following institutionalization: The nursing home admission-burden and nursing home admission-depression prognostic tools. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33(5):624–646. doi: 10.1177/0733464812454008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Prigerson HG, Kiely DK, Schaffer ML, Mitchell SL. Grief among family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19:543–550. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcbe0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:683–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JM, Currier JM, Gallagher-Thompson D. Outcomes from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer's caregiver health (REACH) program for bereaved caregivers. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(1):190–202. doi: 10.1037/a0014303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley CK, Mast BT. The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):388–396. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Smit F, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, van de Ven P, et al. van Hout HPJ. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? A randomized trial. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e30936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer B. Gain in the caregiving experience: Where are we now? What next? Gerontologist. 1997;37(2):218–232. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely DK, Prigerson H, Mitchell SL. Health care proxy grief symptoms before the death of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(8):664–673. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181784143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konisberg RD. The Truth About Grief: The Myth of Its Five Stages and the New Science of Loss. NY: Simon & Schuster; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. NY: Touchstone; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross E, Kessler D. On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss. NY: Scribner; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Large S, Slinger R. Grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease and related dementia: A qualitative synthesis. Dementia. 2013;0(0):1–20. doi: 10.1177/1471301213494511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindauer A, Harvath TA. Pre-death grief in the context of dementia caregiving: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1111/jan.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace NL, Rabins PV. The 36-Hour Day: A Family Guide to Caring for People with Alzheimer Disease, Other Dementias, and Memory Loss in Later Life. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press Health Book; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA. 2007;297(7):716–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen R, Birkelund R. ‘The path through the unknown’: The experience of being a relative of a dementia-suffering spouse or parent. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2013;22:3024–3031. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: Toward an individual differences model. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(6):1805–1831. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Robinaugh D, Shear K, Bonanno GA. Does attachment avoidance help people cope with loss? The moderating effects of relationship quality. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(10):1127–1136. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwit SJ, Meuser TM. Development and initial validation of an inventory to assess grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):751–765. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuser TM, Marwit SJ. A comprehensive, stage-sensitive model of grief in dementia caregiving. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):658–670. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuser TM, Marwit SJ, Sanders S. Assessing grief in family caregivers. In: Doka KJ, editor. Living with Grief: Alzheimer's disease. Washington, DC; Hospice Foundation of America; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, Epstein C, Pierzchala A. Counseling the Alzheimer's Caregiver: A Resource for Health Care Professionals. American Medical Association Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA. Bereavement and the quest for meaning: Rewriting stories of loss and grief. Hellenic Journal of Psychology. 2006;3:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Prigerson HG, Davies B. Mourning and meaning. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;46(2):235–251. doi: 10.1177/000276402236676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes BB, Hill RD, Hicken BL, Luptak M, Rupper R, Dailey NK, Bair BD. The role of grief in dementia caregiving. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias. 2010;25(1):9–17. doi: 10.1177/1533317509333902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Kelber ST, Blaylock M. “Easing the Way” for Spouse Caregivers of Individuals with Dementia: A pilot feasibility study of a grief intervention. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2010;3(2):89–99. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100302-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Lueger RJ, Kelber ST, Prigerson HG. Spousal bereavement in older adults: Common, resilient, and chronic grief with defining characteristics. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(4):332–341. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243890.93992.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Sanders S, Kelber ST. Grief and personal growth experience of spouses and adult-child caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):798–809. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Mullan J, Semple S, Skaff M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorenson S. Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: A meta-analytic comparison. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8(5):438–449. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001725036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. Grief and acceptance as opposite sides of the same coin: Setting a research agenda to study peaceful acceptance of loss. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;193:435–437. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA. Clinical Dimensions of Anticipatory Mourning. Chicago, IL: Research Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson VE. A dual process model of grief counseling: Findings from the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2007;48:311–329. doi: 10.1300/J083v48n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson VE. Length of caregiving and well-being among older widowers: Implications for the dual process model of bereavement. Omega. 2010;61(4):333–356. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.4.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanoff BD, Terenzio M. Rituals and the grieving process. Death Studies. 1998;22:697–711. doi: 10.1080/074811898201227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Dagley JC. An assessment of anticipatory grief as experienced by family caregivers of individuals with dementia. Alzheimer's Care Today. 2009;10(1):8–21. doi: 10.1097/ACQ.0b013e318197427a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C. Grief: The Mourning After: Dealing with Adult Bereavement. 2nd. NY: Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S, Ott CH, Kelber ST, Noonan P. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease and related dementia. Death Studies. 2008;32:495–523. doi: 10.1080/07481180802138845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S, Corley CS. Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Social Work in Health Care. 2003;37(3):35–53. doi: 10.1300/J010v37n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli RB. The Alzheimer's Family: Helping Caregivers Cope. NY: Norton; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santulli RB, Blandin K. The Emotional Journey of the Alzheimer's Family. Lebanon, NH: Dartmouth College; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shear K. Complicated grief treatment: The theory, practice and outcomes. Bereavement Care, 2010 January 1. 2010;(3):29. 10–14. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2010.522373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: A prospective study of bereavement. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck P, Reynolds C., III Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuter P, Beattie E, Edwards H. An exploratory study of grief and health-related quality of life for caregivers of people with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2013;29(4):379–385. doi: 10.1177/1533317513517034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg E. Introducing the 3-A grief intervention model for dementia caregivers: Acknowledge, assess and assist. Omega. 2007;54(3):215–235. doi: 10.2190/D1R5-0473-1922-4N70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut HAW. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies. 1999;23:1–23. doi: 10.1080/074811899201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Boerner K. Continuing bonds in adaptation to bereavement: Toward theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Folkman S, Hansson RO, Schut H. The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:2440–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RJ, Pomeroy EC. The impact of anticipatory grief on caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 1997;16(1-2):55–76. doi: 10.1300/J027v16n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews FE. Survival times in people with dementia: Analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ. 2008;336(7638):258–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39433.616678.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]