Abstract

This study analyzed event-level partnership data from a computer-assisted survey of 719 gay and bisexual men (GBM) enrolled in the Momentum Health Study to delineate potential linkages between anal sex roles and so-called “sex drugs”, i.e. erectile dysfunction drugs (EDD), poppers and crystal methamphetamine. Univariable and multivariable analyses using generalized linear mixed models with logit link function with sexual encounters (n=2,514) as the unit of analysis tested four hypotheses: 1) EDD are significantly associated with insertive anal sex roles, 2) poppers are significantly associated with receptive anal sex, 3) both poppers and EDD are significantly associated with anal sexual versatility and, 4) crystal methamphetamine is significantly associated with all anal sex roles. Data for survey respondents and their sexual partners allowed testing these hypotheses for both anal sex partners in the same encounter. Multivariable results supported the first three hypotheses. Crystal methamphetamine was significantly associated with all anal sex roles in the univariable models, but not significant in any multivariable ones. Other multivariable significant variables included attending group sex events, venue where first met, and self-described sexual orientation. Results indicate that GBM sex-drug use behavior features rational decision-making strategies linked to anal sex roles. They also suggest that more research on anal sex roles, particularly versatility, is needed, and that sexual behavior research can benefit from partnership analysis.

Keywords: sexual partnerships, event-level data, anal sex roles, gay and bisexual men, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Research with North American gay and bisexual men (GBM) consistently indicates strong linkages between substance use and sexual behavior (Stall & Purcell, 2000; Green & Halkitis, 2006; Ostrow et al., 2008; Vosburgh et al., 2012; Frederick & Perrone 2014). These linkages feature the use of “recreational” or “club” drugs, including alcohol, cocaine, marijuana/hashish, crystal methamphetamine, GHB, and ketamine, and “sex drugs” represented by crystal methamphetamine, erectile dysfunction drugs (EDD) and amyl nitrates (poppers) taken to enhance, facilitate or prolong sexual pleasure (Mansergh et al. 2006; Semple et al. 2009). Disinhibition (Aguilando & Myers, 2008) and Expectancy Theory (Wells et al., 2011) interpret this behavior as a two-step process in which recreational drugs reduce inhibitions, often leading to high risk sex. As a result, understanding linkages between specific substances and GBM high risk sex is an important research focus (Gilmore et al., 2002; Colfax et al., 2004; Fisher et al., 2006, 2010).

Earlier attempts to delineate linkages used global and/or situational assessments to measure substance use and sexual behavior over specified time periods, for example within the past three months. Results yielded mixed results ranging from no associations (Weatherburn et al., 1993) to strong linkages (Gillmore et al., 2002; Colfax et al., 2004). The subsequent adoption of event-level assessment, measuring substances used and sexual behaviors pertaining to a specific sexual encounter within a highly restricted time period, e.g. 2-4 hours before or during sex (Leigh & Stall, 1993), eliminated some, but not all, earlier methodological problems. Remaining problems include the lack of a standardized definition of “high risk sex” and consistent measures of substance use. In the first regard, while anal sex is recognized as the primary HIV infection route among GBM due to a transmission probability approximately 18 times that of vaginal intercourse (Baggely et al., 2010), there is no consensus on what constitutes high risk anal sex, e.g. any anal sex, condomless anal sex, receptive anal sex, etc. Currently, regional social and/or biomedical differences exacerbate standardization attempts. For example, in British Columbia where a provincial Treatment as Prevention program resulted in high HAART prevalence among GBM (Montaner et al., 2014), HIV-negative men who attended group sex events reported having anal sex with HIV-positive men on HAART as sero-adaptive, not high risk, behavior (Roth et al., 2014). Similarly, different measures of substance use, e.g. alcohol use versus binge drinking, resulted in a recent meta-analysis of event-level studies of GBM substance use and sexual risk behavior to note, “Due to the heterogeneity of the substance use measures and the varied definitions of the sexual risk behavior measures, we determined that a meta-analysis was not the most appropriate approach.” (Vosburgh et al., 2012: 1396).

In addition, most event-level analyses for GBM have not considered anal sex versatility, when men report both insertive and receptive anal sex in the same encounter (Moskowitz et al., 2008). Yet research indicates that the majority of GBM self-identify as versatile (Hart et al., 2003), and practice sexual versatility. For example, in a national Australian on-line survey of GBM over forty years of age (n=1,135) 62% of participants engaged in insertive and receptive anal sex in the past year (Lyons et al., 2013), while another Australian study of over 800 GBM reported that 20% practiced versatility in their last anal sex episode (Lyons et al., 2011). An additional limitation is that event-level studies usually gather data only on participants’ sexual behavior and substance use, not their partners’ (for an exception see Colfax et al., 2004). Yet all three sex drugs listed above have potential linkages to specific anal sex roles, and should vary within sexual dyads. EDD, including sildenafil, manufactured by Pfizer as Viagra®, tadalafil sold as Cialis® by Lilly and vardenafil produced as Levitra® by GlaxoSmithKline appear associated with the insertive role (Fisher et al., 2006). Poppers relax smooth muscles, facilitating penis-anus penetration, and are associated with receptive anal intercourse (Drumright et al., 2009). Finally, crystal methamphetamine is taken to heighten sexual pleasure during both insertive and receptive anal sex (Green & Halkitis, 2006), and because one physiological effect is to decrease erectile function, resulting in so-called “drug dick” or “crystal dick” (Holt, 2009), crystal methamphetamine is reportedly combined with EDD during insertive anal sex (Mansergh et al., 2006).

To address the last two methodological concerns, this study uses event-level partnership data to test four hypotheses related to GBM anal sex roles and substance use. These predict that: 1) EDD are significantly associated with insertive anal sex roles, 2) poppers are significantly associated with receptive anal sex, 3) both poppers and EDD are significantly associated with versatile/reciprocal anal sex and, 4) crystal methamphetamine is significantly associated with all three anal sex roles. Reported event-level data for study participants and their sexual partners permitted hypotheses testing for both members of an anal sex dyad. For example, we predicted that a respondent reporting insertive anal sex would use EDD, his partner in the receptive anal sex role would use poppers, and both would take crystal methamphetamine during this sexual encounter.

METHODS

Protocol

Study data were collected by the Momentum Health Study, which used respondent-driven sampling (RDS, Heckathorn, 1997) to recruit HIV-positive and HIV-negative GBM in Vancouver, British Columbia. RDS was developed for “hidden” populations, i.e. those not amenable to a probability-based sampling scheme, and begins by recruiting “seeds” who share key characteristics, e.g. gender, sexual orientation, substance use, with a target population's network. These respondents in turn recruit a fixed number of others in a long-chain sampling approach. Successive recruitment waves permit population parameter estimation via Markov Chain procedures (Volz et al., 2012). As described fully in Forrest et al. (2014), Momentum seeds distributed paper and/or electronic vouchers to Vancouver GBM. Recipients presented these vouchers at the downtown Vancouver study office where they were screened for study eligibility criteria, which included being 16 years of age and older, identifying as a man, having had sex with other men in the past six months, living in the Greater Vancouver Area region, and competency in understanding and completing a questionnaire written in English. Eligible participants completed a computer assisted self-interview (CASI) questionnaire and biological tests including point of care HIV testing, blood tests for hepatitis C and syphilis serology, and optional tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Participants received a fifty dollar honorarium, received a maximum of six vouchers to recruit other participants, and earned an additional ten dollars for each eligible participant who completed the survey and biological tests. Study procedures received human ethics clearances from Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Victoria. Altogether, a total of 719 GBM, recruited from February 2012 - February 2014, including 119 (16.6%) seeds, were included in this analysis.

The CASI asked about sexual, behavioral, socio-demographic and substance use patterns. One section asked participants to describe their most recent sexual encounters for up to five of their last male sexual partners in the past six months. Group sex events were not included in this section. For each encounter participants described how they first met their partner (in-person, online), how long they knew each other, specific sexual acts performed (receptive and/or insertive anal sex, with and without a condom, receiving and/or giving oral sex, masturbation, fisting, rimming, using sex toys), partner's age relative to the participant, partners’ HIV status.

Analysis

The questionnaire asked about substances participants and their partners used within two hours of or during sex, meeting the definition for event-level associations. Responses gathered in this manner constitute “one with many” or “partner by partner” data (Mustanski et al., 2014), with each partner's information nested within the respondent's and therefore interdependent. To account for interdependence we used generalized linear mixed models with logit link function (Allison, 2012) to test the hypotheses, and made sexual encounters (n=2,154) the unit of analysis. SAS® Version 9.3 PROC GLIMMIX constructed separate models for receptive, insertive and versatile anal sex roles. Independent variables with probability values <0.05 were selected from initial univariable models for inclusion in subsequent multivariable models. Final model selection was conducted for each model using a backward elimination procedure based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Type III P-value and included Adjusted Odds Ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (Lima et al., 2007). Socio-demographic data were adjusted by the RDS program RDSAT version 7.1 (Volz et al., 2012) using respondents’ social network size estimates and each corresponding variable as the weighting variable. Event level data were not weighted, as these captured information about respondents’ network size only, not their partners.

Dependent Variables

In each model, specific roles reported during every anal sex encounter (receptive n=675, insertive n=632, versatile n=358), were contrasted with reporting only non-anal intercourse sexual behavior, which included oral sex (fellatio and rimming), masturbation, etc. (n=849).

Independent Variables

Independent variables included respondents’ age, serostatus as determined by a point-of-care HIV test, sexual orientation, ethnicity, annual income, education, residence, where partners first met, whether the participant had a regular partner, group sex event attendance in the past 6 months, and whether more than one sex partner was involved in the reported sexual event. Psychosocial measures included four multiple-item validated scales: 1) the McKirnan et al. (2001) Sexual Escape Scale (12 questions, Cronbach's study α = 0.90), 2) the Kalichman et al. (1994) Sensation Seeking Scale (Revised) (11 questions, study α = 0.73), 3) the Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983; 14 questions, study α = 0.87), and 4) a Treatment Optimism Scale, adapted from Van de Ven et al. (2001, 12 questions, plus 2 additional items, study α = 0.85). Substance questions asked whether respondents and/or their partners used alcohol, marijuana, EDD, poppers, crystal methamphetamine, Ecstasy/MDMA, GHB, powdered cocaine, crack cocaine, or ketamine two hours before or during the reported sexual event.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

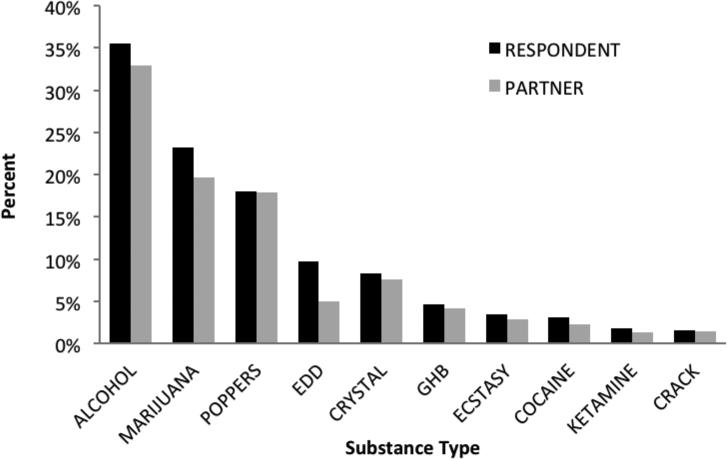

Table 1 shows the sample's basic socio-demographic data. Overall, the sample of 719 GBM was predominantly White and well educated, with a median age of 33 years (IQR 26 - 47) and with a RDS-adjusted HIV prevalence of 23.0%. Based on RDS predictions, gay, White men with annual incomes from $30,000-$59,999, or greater than a high school education were over-represented, while men who self-described their sexual orientation as bisexual/other, had annual income below $30,000, and not educated beyond high school were under-sampled. Across all 2,514 sexual events, 849 had no anal intercourse reported. 675 had receptive-only anal intercourse reported, 632 had insertive-only anal intercourse reported, and 358 had both receptive and insertive anal intercourse reported (i.e., were versatile events). Participants reported a median of four (mean = 3.54, standard deviation = 1.54, mode =5) of the possible five sexual partners. Prevalence of any reported substance use was consistent across sexual positions for participants (68% of all anal sex acts, 66% for insertive, 69% for receptive and 71% for versatile roles), and for their partners, although the latter were lower (60% of all anal sex acts, 58 % for insertive, 62% for receptive and 63% for versatile roles). Figure 1 presents the ten most commonly reported substances by participants and partners. Rank order of substances reported is almost identical for both.

Table 1.

Crude and RDS weighted sample characteristics (n=719).

| Variable | Count | Crude % | RDS weighted % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Orientation | Gay | 612 | 85.1 | 79.9 (75.1, 84.8) |

| Bisexual/Other | 107 | 14.9 | 20.1 (15.2, 24.8) | |

| Age | < 30 | 275 | 38.3 | 34.4 (26.2, 43.2) |

| ≥ 30 | 444 | 61.8 | 65.6 (56.8, 73.8) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 539 | 75.0 | 67.8 (60.4, 73.9) |

| Asian | 72 | 10.0 | 9.7 (6.3, 14.9) | |

| Aboriginal | 50 | 7.0 | 10.8 (5.9, 16.6) | |

| Other | 58 | 8.1 | 11.7 (7.1, 17.4) | |

| Annual Income ($CAD) | 0-29,999 | 457 | 63.6 | 75.0 (69.7, 80.3) |

| 30,000-59,999 | 182 | 25.3 | 16.8 (13.0, 20.7) | |

| 60,000 or more | 80 | 11.1 | 8.2 (5.1, 11.7) | |

| Education | No greater than high school | 154 | 21.8 | 29.6 (24.1, 37.8) |

| Greater than high school | 551 | 78.2 | 70.4 (62.2, 75.9) | |

| Residence | Downtown Vancouver | 356 | 49.5 | 52.1 (44.3, 59.5) |

| Other Vancouver area | 233 | 31.0 | 31.1 (24.7, 37.3) | |

| Greater Vancouver | 133 | 18.4 | 15.9 (11.4, 21.8) | |

| Outside Greater Vancouver | 7 | 1.0 | 0.8 (0.3, 1.9) | |

| HIV POC* Final Result | Negative | 520 | 72.3 | 77.0 (69.3, 84.5) |

| Positive | 199 | 27.7 | 23.0 (15.5, 30.7) |

POC = “point-of-care” test

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of respondents’ and their partners’ substance use during most recent sex with 5 most recent partners

Generalized Linear Mixed Model Logistic Regressions

Tables 2-4 present univariable and multivariable generalized linear mixed model logistic regression results for receptive, insertive and versatile anal sex respectively for all 2,514 sexual encounters reported. For receptive anal sex results, shown in Table 2, in the final multivariable model participants were significantly less likely to report receptive anal sex if they were non-gay-identified, and if they met their partner anywhere but online or via a digital app. In contrast, participants were more likely to be HIV-positive and to have attended group sex events within the past 6 months. Table 2 also shows that for participants EDD, crystal methamphetamine and poppers had statistically significant positive associations in the univariable model though only poppers remained significant in the multivariable model. Partner EDD use in the insertive role was not significantly associated in either univariable or multivariable models. Turning to insertive sex roles, Table 3 shows EDD significantly positively associated with participants, while poppers were significantly negatively associated with partners taking the receptive role. Group sex attendance and multiple substances were significant for participants (marijuana, crystal methamphetamine, GHB) and their partners (crystal methamphetamine, GHB, Ecstasy), in the univariable model, but not in the multivariable model. For the versatile events, shown in Table 4, EDD, poppers, marijuana and group sex attendance were significant variables in the multivariable model. Other substances, including crystal methamphetamine, ketamine, GHB and Ecstasy for participants and marijuana, poppers, EDD GHB and Ecstasy for partners were significant in the univariable but not multivariable models.

Table 2.

Receptive anal sex (Yes = 675 vs. No = 849) univariable and multivariable mixed logistic regression model results.

| VARIABLE | UNIVARIABLE MODEL OR (95% CI) | MULTIVARIABLE MODEL AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Orientation | Bisexual/Other VS Gay | 0.39 (0.20, 0.77) | 0.49 (0.25, 0.93) |

| Age | Continuous | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | |

| Ethnicity | Asian VS White | 1.18 (0.58, 2.42) | |

| Aboriginal VS White | 2.78 (1.02, 7.57) | ||

| Other VS White | 2.20 (0.98, 5.93) | ||

| Annual Income | $30-60K VS <$30K | 0.61 (0.36, 1.04) | |

| ≥$60 VS <$30K | 0.74 (0.35, 1.55) | ||

| Education>High School | Yes VS No | 0.70 (0.40, 1.23) | |

| Residence | Vancouver VS | 1.02 (0.61, 1.69) | |

| Downtown | |||

| Greater Vancouver VS | 1.37 (0.74, 2.52) | ||

| Downtown | |||

| Outside Vancouver VS | 0.65 (0.04, 9.87) | ||

| Downtown | |||

| HIV POC* Result | Positive VS Negative | 2.35 (1.43, 3.87) | 1.80 (1.09 – 2.98) |

| Regular Partner | Yes VS No | 0.93 (0.57, 1.54) | |

| Attended Sex Parties | Yes VS No | 2.85 (1.72, 4.72) | 2.18 (1.32, 3.59) |

| Sensation Seeking Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | |

| Treatment Optimism Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | |

| Cognitive Escape Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Depression/Anxiety Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| First Met Partner | Sex/Premises VS Digital | 1.97 (1.00, 3.85) | 1.30 (0.65, 2.58) |

| In Person VS Digital | 0.62 (0.43, 0.90) | 0.64 (0.42, 0.93) | |

| Other VS Digital | 0.44 (0.24, 0.81) | 0.45 (0.24, 0.83) | |

| Other People Involved | Yes VS No | 1.18 (0.71, 1.95) | |

| Used Alcohol | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.21 (0.85, 1.71) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) | ||

| Used Marijuana | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.53 (0.98, 2.38) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.38 (0.89, 2.15) | ||

| Used EDD** | Participant: Yes VS No | 2.12 (1.03, 4.37) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.86 (0.77, 4.46) | ||

| Used Poppers | Participant: Yes VS No | 4.18 (2.58, 6.78) | 3.02 (1.85, 4.92) |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 2.42 (1.49, 3.94) | Not Selected+ | |

| Used Crystal Meth | Participant: Yes VS No | 2.74 (1.35, 5.57) | Not Selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.94 (0.91, 4.16) | ||

| Used GHB | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.93 (0.79, 4.71) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.64 (0.67, 4.03) | ||

| Used Ecstasy/MDMA | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.18(0.47, 2.98) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.55 (0.53, 4.51) | ||

| Used Cocaine Powder | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.87 (0.74, 4.70) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.49 (0.55, 4.07) | ||

| Used Crack Cocaine | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.70 (0.46, 6.31) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.64 (0.67, 4.03) | ||

| Used Ketamine | Participant: Yes VS No | 0.69 (0.18, 2.63) | |

| Partner Yes VS No | 0.83 (020, 3.48) |

POC = “point-of-care” test

EDD = “erectile dysfunction drugs”

NB: Statistically significant (p<0.05) results in bold. OR = Odds Ratio. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Model selection was conducted for each model using a backward elimination procedure based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Type III P-value.

Table 4.

Versatile anal sex (Yes = 358 vs. No = 849) univariable and multivariable mixed logistic regression model results.

| UNIVARIABLE MODEL | MULTIVARIABLE MODEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLE | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Sexual Orientation | Bisexual/Other VS Gay | 0.69 (0.32 1.49) | |

| Age | Continuous | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |

| Ethnicity | Asian VS White | 0.71 (0.29, 1.71) | |

| Aboriginal VS White | 1.30 (0.36, 4.68) | ||

| Other VS White | 2.48 (0.97, 6.34) | ||

| Annual Income | $30-60K VS <$30K | 0.75 (0.40, 1.39) | |

| ≥$60 VS <$30K | 1.92 (0.85, 4.38) | ||

| Education>High School | Yes VS No | 0.99 (0.50, 1.96) | |

| Residence | Vancouver VS Downtown | 0.88 (0.48, 1.61) | |

| Greater Vancouver VS Downtown | 1.09 (0.52, 2.28) | ||

| Outside Vancouver VS Downtown | 0.61 (0.02,15.32) | ||

| HIV POC* Result | Positive VS Negative | 1.95 (106, 3.55) | Not selected+ |

| Regular Partner | Yes VS No | 1.33 (0.73, 2.40) | |

| Attended Sex Parties | Yes VS No | 2.87 (1.56, 5.25) | 2.02 (1.08, 3.80) |

| Sensation Seeking Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Treatment Optimism Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Cognitive Escape Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Depression/Anxiety Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| First Met Partner | Sex/Premises VS Digital | 1.88 (0.78, 4.55) | |

| In Person VS Digital | 0.81 (0.52, 1.28) | ||

| Other VS Digital | 0.53 (0.24, 1.16) | ||

| Other People Involved | Yes VS No | 1.58 (0.88, 2.85) | |

| Used Alcohol | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.18 (0.77, 1.83) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.96 (0.62, 1.49) | ||

| Used Marijuana | Participant: Yes VS No | 2.86 (1.66, 4.94) | 2.01 (1.16, 3.50) |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 2.20 (1.29, 3.77) | Not selected+ | |

| Used EDD** | Participant: Yes VS No | 9.96 (4.52,21.97) | 7.65 (3.39,17.26) |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 5.33 (2.27,12.54) | Not selected+ | |

| Used Poppers | Participant: Yes VS No | 4.56 (2.44, 8.54) | 3.18 (1.65, 6.12) |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 3.18 (1.75, 5.77) | Not selected+ | |

| Used Crystal Meth | Participant: Yes VS No | 6.54 (2.82,15.20) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 7.57 (3.26,17.55) | Not selected+ | |

| Used GHB | Participant: Yes VS No | 5.36 (1.91,15.05) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 2.86 (1.04, 7.85) | Not selected+ | |

| Used Ecstasy/MDMA | Participant: Yes VS No | 3.45 (1.21, 9.84) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 3.78 (1.24,11.52) | Not selected+ | |

| Used Cocaine Powder | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.70 (0.53, 5.51) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.93 (0.25, 3.56) | ||

| Used Crack Cocaine | Participant: Yes VS No | 0.44 (0.07, 2.80) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.50 (0.08, 3.33) | ||

| Used Ketamine | Participant: Yes VS No | 4.76 (1.17,19.35) | Not Selected+ |

| Partner : Yes VS No | 3.63 (0.81,16.26) |

POC = “point-of-care” test

EDD = “erectile dysfunction drugs”

NB: Statistically significant (p<0.05) results in bold. OR = Odds Ratio. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Model selection was conducted for each model using a backward elimination procedure based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Type III P-value.

Table 3.

Insertive anal sex (Yes = 632 vs. No = 849) univariable and multivariable mixed logistic regression model results.

| UNIVARIABLE MODEL | MULTIVARIABLE MODEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLE | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Sexual Orientation | Bisexual/Other VS Gay | 0.87 (0.46, 1.63) | |

| Age | Continuous | 0.92 (0.97, 1.01) | |

| Ethnicity | Asian VS White | 0.53 (0.25, 1.11) | |

| Aboriginal VS White | 1.36 (0.49, 3.81) | ||

| Other VS White | 1.80 (0.80, 4.02) | ||

| Annual Income | $30-60K VS <$30K | 1.13 (0.68, 1.87) | |

| ≥$60 VS <$30K | 1.71 (0.85, 3.44) | ||

| Education>High School | Yes VS No | 0.77 (0.44, 1.35) | |

| Residence | Vancouver VS Downtown | 0.71 (0.43, 1.18) | |

| Greater Vancouver VS Downtown | 1.14 (0.62, 2.18) | ||

| Outside Vancouver VS Downtown | 0.72 (0.05, 9.66) | ||

| HIV POC* Result | Positive VS Negative | 1.03 (0.61, 1.74) | |

| Regular Partner | Yes VS No | 1.52 (0.93, 2.48) | |

| Attended Sex Parties | Yes VS No | 1.89 (1.08, 3.05) | Not selected+ |

| Sensation Seeking Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Treatment Optimism Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Cognitive Escape Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| Depression/Anxiety Scale | Continuous | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| First Met Partner | Sex/Premises VS Digital | 1.51 (0.71, 3.21) | |

| In Person VS Digital | 0.75 (0.52, 1.08) | ||

| Other VS Digital | 0.58 (0.32, 1.05) | ||

| Other People Involved | Yes VS No | 1.06 (0.70, 1.93) | |

| Used Alcohol | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.01 (0.71, 1.45) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.88 (0.62, 1.26) | ||

| Used Marijuana | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.66 (1.06, 2.59) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.49 (0.96, 2.31) | ||

| Used EDD** | Participant: Yes VS No | 5.25 (2.56,10.77) | 4.69 (2.26, 9.72) |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.57 (0.63, 3.72) | ||

| Used Poppers | Participant: Yes VS No | 2.18 (1.30, 3.66) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 2.86 (1.77, 4.65) | 2.56 (1.56, 4.20) | |

| Used Crystal Meth | Participant: Yes VS No | 2.18 (1.30, 3.66) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 2.63 (1.22, 5.71) | Not selected+ | |

| Used GHB | Participant: Yes VS No | 3.44 (1.34, 8.84) | Not selected+ |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.31 (0.45, 3.79) | ||

| Used Ecstasy/MDMA | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.15 (0.42, 3.14) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.31 (0.45, 3.79) | ||

| Used Cocaine Powder | Participant: Yes VS No | 0.91 (0.32, 2.57) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 1.24 (0.41, 3.73) | ||

| Used Crack Cocaine | Participant: Yes VS No | 1.10 (0.27, 4.48) | |

| Partner: Yes VS No | 0.91 (0.21, 3.88) | ||

| Used Ketamine | Participant: Yes VS No | 0.92 (0.22, 3.87) | |

| Partner : Yes VS No | 1.24 (0.29, 5.25) |

POC = “point-of-care” test

EDD = “erectile dysfunction drugs”

NB: Statistically significant (p<0.05) results in bold. OR = Odds Ratio. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Model selection was conducted for each model using a backward elimination procedure based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Type III P-value.

DISCUSSION

Multivariable analyses of event-level data using generalized linear mixed model with logit link functions tested hypotheses predicting anal sex roles associations with specific sex drugs. Generally, results supported our four hypotheses. Specifically, for the insertive role multivariable model EDD were positively associated with participants, while their receptive role partners were significantly associated with poppers. Similarly, for the multivariable receptive role model participants were significantly more likely to use poppers, although the prediction that their insertive role partners should be more likely to use EDD was not supported in either the univariable or multivariable models. Results from the versatile multivariable model followed our prediction that these GBM should be significantly more likely to use both EDD and poppers. However, their partners, who by definition were also sexually versatile, were significantly more likely to use EDD and poppers in the univariable, but not multivariable model. Our fourth prediction, that crystal methamphetamine should be significant for all multivariable models was not supported. Instead, crystal methamphetamine was statistically significant for both participants and partners in the insertive and versatile univariable models, and for participants in the receptive univariable model, but it was never significant in any multivariable models.

The anal sex role models did not identify many non-sexual recreational drug associations as independent predictors of anal sex positions. Instead, analysis revealed overall high substance use levels, denoted by significant odds ratios for multiple substances in the univariable models, but relatively few in the multivariable models. This was particularly true for sexually versatile men. For example, while many recreational substances were associated at the univariable level with versatile sexual events, only marijuana use remained significant in the multivariable model. Previous research with younger GBMSM in Vancouver found marijuana use within two hours prior to sex was associated with increased odds of condomless anal intercourse, but not condomless receptive anal intercourse (Rusch et al., 2004). Future research will explore these results to determine if they reflect simple substance availability, or specific GBM choices based on perceived psychotropic and sexual effects (Palamar et al., 2013).

Analysis also generated several significant findings for socio-demographic and behavioral independent variables. One notable finding was the positive significant association with attending group sex events in the past six months recorded in the receptive and versatile multivariable models, as well as the insertive univariable model. This supports previous research associating anal sex with group sex events (Prestage et al., 2009). Another important finding was that participants reporting receptive anal sex roles were more likely to be HIV-positive. We interpret this as strategic positioning, since receptive anal sex has higher HIV transmission probabilities (Meng et al., 2014). Similarly, finding that participants not self-identifying as gay (“bisexual/other”) were significantly less likely to engage in receptive anal sex, may indicate a strategic positioning risk reduction strategy for men often viewed as HIV/STI bridge populations to heterosexual women (Green et al., 2013; Godbole et al., 2014). Finally, men reporting only receptive anal sex roles were significantly less likely to meet partners first in person or in other venues (e.g. sex on premises) compared with meeting digitally via the Internet or telephone apps. This raises the issue of how GBM negotiate anal sex roles with their partners. Digital sites can make explicit preferences for “tops”, “bottoms” and/or “versatiles” and recent research indicates GBM attempt to detect sexual role preferences from behavioral and/or physical cues (Tskhay et al., 2014). Future qualitative interviews could help understand decision-making processes of GBM with regard to what type of sex to have, e.g. anal, oral, etc., and what roles to assume for anal sex.

This analysis benefited from event-level data recording both participants and partners’ sexual behavior and substance use. However, we recognize research design limitations. As noted, event data were not weighted by RDS-values, so that the sample cannot represent the Vancouver GBM population. Additionally, these data are not true dyads; instead participants reported on their sexual partners’ characteristics and behaviors. Therefore we could not use dyadic measures such as the intra-class coefficient or Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (Mustanski et al., 2014). Furthermore, the study, for reasons explained earlier, emphasized anal sex roles over sexual risk. This may explain why none of the four psycho-social scales, Hospital Depression and Anxiety, Treatment Optimism, Sensation Seeking and Sexual Escape, were statistically significant in any multivariable analyses. Finally, we asked if participants and/or partners had used alcohol before or during sex. We should have asked about binge drinking, defined as >5 drinks in one sitting for men. Of eleven specific substances (alcohol, binge alcohol drinking, cocaine, crack, ecstasy, EDD, GHB, ketamine, marijuana, methamphetamine and poppers), included in a recent meta-analysis of 23 event-level studies of substance use and sexual risk behavior among GBM (Vosburgh et al., 2012) only two, binge-drinking and crystal methamphetamine use, were consistently associated with sexual risk behavior, regardless of how risk was defined. Not asking about binge drinking may explain why alcohol consumption was not significant in any of the models.

Despite these caveats, this study's results are important for understanding the linkages between substance use and sexual behaviour among GBM. Substance use in this context is sometimes interpreted as reducing not only inhibitions, but also cognitive functioning, resulting in impaired judgement with regard to sexual risk-taking (Aguinaldo & Myers, 2008). This seems paradoxical in light of our findings that the use of sex drugs reflects rational, predetermined decision-making based upon specific anal sex roles. One important theoretical linkage between specific substance use and sexual behavior lies in social norms and expectations surrounding substance use and sex, as stressed by Wells et al. (2011). Thus, in a study of crystal methamphetamine among Manhattan GBM one study participant stated:

I use it [crystal] for specific sexual encounters, if I know that there is gonna be certain activities involving anal sex that I might need to loosen up or be a lot less inhibited.

(Green & Halkitis, 2006, p. 323)

The above indicates rationale decision-making processes for sex-drug use that include both psychological and physical concerns. Beyond the focus on anal sex roles presented here, a fuller understanding of GBM decision-making processes is important for other aspects of mental and sexual health.

Future research could benefit from adopting sexual partnerships/dyads as the unit of analysis. As detailed in a recent special issue of this journal devoted to the sexual health of GBM couples (Mustanski & Parsons, 2014; Mustanski et al., 2014) a sample of important health topics suitable for sexual partnership analyses include HIV/STI testing and counseling, sexual behavior agreements, and acceptability of bio-medical innovations exemplified by pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research [107544]; National Institutes for Health, National Institute for Drug Abuse [R01DA031055] and Health Canada. We thank our community colleagues at the Health Initiative for Men, YouthCO HIV & HepC Society of BC, and Positive Living BC for their support. We also thank the research participants for sharing their important data with the Momentum Health Study. DMM is supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The co-authors acknowledge that they have no financial interest or benefit arising from the direct application of this research to disclose.

REFERENCES CITED

- Aguinaldo J, Myers T. A discursive approach to disinhibition theory: The normalization of unsafe sex among gay men. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:167–181. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. Logistic regression using SAS. SAS Press; Cary, NC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley R, White R, Boily M-C. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39:1048–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Coates TJ. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(10):1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Gorbach PM, Little SJ, Strathdee SA. Associations between substance use, erectile dysfunction medication and recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(2):328–336. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Malow R, Rosenberg R, Reynolds GL, Farrell N, Jaffe A. Recreational Viagra use and sexual risk among drug abusing men. American Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;2:107. doi: 10.3844/ajidsp.2006.107.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Reynolds G, Napper L. Use of crystal meth, Viagra and sexual behaviour. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2010;23:53–56. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334de0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest JI, Stevenson B, Rich A, Michelow W, Pai J, Jollimore J, Roth EA. Community mapping and respondent-driven sampling of gay and bisexual men's communities in Vancouver, Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2014;16(3):288–301. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.881551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick B, Perrone D. “Party N Play” on the Internet: Subcultural formation, Craigslist, and escaping from stigma. Deviant Behavior. 2014;35:859–884. [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore M, Morrison D, Leigh B, Hoppe M, Gaylord J, Rainey D. Does “high = high risk”? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:361–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gobdole S, Sane S, Kamble P, Raj Y, Dulhani N, Venkatsh S, Risbud A. Predictors of bisexual behavior among MSM attending intervention sites may help in prevention interventions for this bridge to the heterosexual epidemic in India: Data from HIV sentinel surveillance. PLOS One. 2014;9(9):e107439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107439. doi:10 1371/journal/pone 0107439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Halkitis P. Crystal methamphetamine and sexual sociality in an urban gay subculture: An elective affinity. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2006;8:317–333. doi: 10.1080/13691050600783320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E, Frye V, Mansergh G, Colfax G, Hudson S, Flores, Hoover D, Bonner S, Kobin B. Correlates of unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse with women among substance-using men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(3):889–899. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, Wolitski RJ, Purcell DW, Gomez C, The Seropositive Urban Men's Study Team Sexual behavior among HIV positive men who have sex with men: What's in a label? Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:179–188. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn D. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Holt M. ‘Just take Viagra’: Erectile insurance, prophylactic certainty and deficit correction in gay men's accounts of sexuopharmaceutical use. Sexualities. 2009;12:746–764. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Johnson J, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, Kelly J. Sexual sensation seeking: scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;62:385–397. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1035–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Geller J, Bangsberg DR, Patterson TL, Daniel M, Kerr T, Hogg RS. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21:1175–1183. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, Smith G, Grierson J, Smith A, McNally S, Couch M. Versatility and HIV vulnerability: Investigating the proportion of Australian gay men having both insertive and receptive anal intercourse. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8:2164–2171. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, Grierson J. Versatility and HIV vulnerability: Patterns of insertive and receptive anal sex in a national sample of older Australian gay men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:1370–1377. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Shouse R, Marks G, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S, Colfax G. Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82:131–134. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan D, Vanable P, Ostrow D, Hope B. Expectancies of sexual “escape” and sexual risk among drug and alcohol-involved gay and bisexual men. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:137–54. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Zou H, Fan S, Zheng B, Zhang L, Dai X, Lu B. Relative risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men engaging in different roles in anal sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis on global data. AIDS and Behavior. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J, Lima V, Harrigan P, Lourenço L, Yip B, Nosyk B, Kendall P. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the “HIV Treatment as Prevention” experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz D, Rieger G, Roloff M. Tops, bottoms and versatiles. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2008;23:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Parsons JT. Introduction to the special section on sexual health in gay and bisexual male couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):17–19. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Starks T, Newcomb M. Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0215-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow D, Stall R. Alcohol, tobacco and drug use among gay and bisexual men. In: Wolitiski R, Stall R, Valdiserri E, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- Palamar J, Kiang M, Stornholm E, Halkitis P. A qualitative descriptive study of perceived sexual effects of club drug use in gay and bisexual men. Psychology and Sexuality. 2014;5(2):143–160. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2012.679363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage G, Hudson J, Down I, Bradley J, Corrigan N, Hurley M, Grulich, McInnes D. Gay men who engage in group sex are at increased risk of HIV infection and onward transmission. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:724–730. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth E, Rich A, Birch R, Jollimore J, Howard T. Applying the concept of positive deviance to group sex events.. Paper presented at the Gay Men's Health Summit; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Oct, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch M, Lampinen TM, Schilder A, Hogg RS. Unprotected anal intercourse associated with recreational drug use among young men who have sex with men depends on partner type and intercourse role. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31(8):492–498. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135991.21755.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple S, Zians J, Strathdee S, Patterson T. Sexual marathons and methamphetamine use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Purcell D. Intertwining epidemics: A review of research on substance use among men who have sex with men and its connection to the AIDS epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tskhay KO, Re DE, Rule NO. Individual differences in perceptions of gay men's sexual role preferences from facial cues. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(8):1615–1620. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven P, Crawford J, Kippax S, Knox S, Prestage G. A scale of optimism–scepticism in the context of HIV treatments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:171–176. doi: 10.1080/09540120050001841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E, Wejnert C, Cameron C, Spiller M, Barash V, Degani I, Heckathorn D. Respondent-Driven sampling analysis tool (RDSAT) Version 7.1. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh H, Mansergh G, Sullivan P, Purcell D. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1394–1410. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn P, Davies P, Hickson F, Hunt A, Mcmanus T, Coxon A. No connection between alcohol use and unsafe sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 1993;7:115–119. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells B, Golub S, Parsons J. An integrated theoretical approach to substance use and risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A, Snaith R. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]