Abstract

Objective

In 2012, CDC's Division of Viral Hepatitis launched a public health initiative to increase hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection testing for those at risk and to improve linkage to medical care for those infected. We describe testing outcomes of previously unidentified people at risk for HBV and HCV infection and the lessons learned while linking patients to care.

Methods

CDC's Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care (HepTLC) initiative provided 34 financial awards to U.S. organizations that serve people at risk for viral hepatitis, 25 of which focused on HCV and nine of which focused on HBV. Grantees offered testing and test result notification to people at risk for HBV and/or HCV infection, as well as counseling, referral, and verification or notification of linkage to care for people with positive test results. We entered demographic data, self-reported risk factors, country of origin (for HBV), and testing outcomes into a confidential database.

Results

The 34 grantees tested 87,860 people at more than 260 sites in 17 states. Of the 23,144 people tested for HBV, 1,317 (6%) were positive. Of the 64,716 people tested for HCV, 57,570 (89%) received an HCV antibody (anti-HCV) test, of whom 7,580 (13%) tested anti-HCV positive. Of the 4,765 people who received an HCV RNA test, 3,449 (72%) tested positive. Of the 4,766 people who tested positive for either HBV or HCV infection, 2,116 (44%) were linked to care.

Conclusion

Interventions targeting people at risk for HBV and HCV infection reached a substantial number of people for whom testing is recommended and identified a large proportion of those who had previously unrecognized infection. Patient navigation was critical for follow-up and linkage to care.

In the United States, 800,000 to 1.4 million people are living with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection,1 and an estimated 2.7 million people are living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Among those with HBV infection, up to 70% were born in Asia, Africa, or other regions where HBV is moderately or highly endemic (i.e., hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg] prevalence ≥2%). Most of these people were infected at birth or during early childhood and were usually asymptomatic until advanced liver disease developed. Fewer than half of those infected with HBV living in the United States are aware of their infection, and an even smaller proportion is receiving recommended medical monitoring and care.3 Similarly, few people with HCV infection have been tested, and 45%–85% are unaware of their infection.4 Among those identified with HCV infection in the United States, an estimated 32%–38% have been referred to care, 20%–23% have had HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) testing for evidence of active infection (viremia), and 7%–11% have been treated.5–7

However, advances in viral hepatitis treatment and new practice guidelines for management of patients with chronic HBV and HCV infection could curb rising viral hepatitis-related morbidity and mortality.8,9 The low proportions of people infected with HBV and HCV who are tested and treated reflect a considerable gap in health-care delivery at every stage of the care continuum. A 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report noted these gaps in HBV and HCV testing and care and highlighted viral hepatitis-associated morbidity and mortality; documented barriers to reducing the incidence of viral hepatitis;10 and prompted development of the first-ever U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) national strategy for addressing the prevention, care, and treatment of viral hepatitis in the United States in 2011.11

Since publication of the IOM and HHS reports, many efforts have been undertaken to combat viral hepatitis. To increase the proportion of people who are aware of their viral hepatitis infection and receive care, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued recommendations for risk-based HCV testing and one-time HCV testing for people born between 1945 and 1965,12,13 as well as risk-based HBV testing and testing for foreign-born people from countries with a high prevalence of HBV infection.1,14 CDC-developed educational campaigns further promoted testing by targeting people at risk for HBV and HCV infection and the clinicians who care for them.15 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines for screening, diagnosis, and management of patients chronically infected with HBV and HCV have been recently updated.8,9

We assessed testing outcomes of previously unidentified people at risk for viral hepatitis infection and identified lessons learned during implementation of CDC's Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care (HepTLC) initiative.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

In 2012, guided by recommendations and national priorities for the prevention, care, and treatment of viral hepatitis, the U.S. Congress supported CDC in increasing testing and linkage to care through the Prevention and Public Health Fund and the HHS Secretary's Discretionary Funds. HepTLC awarded two-year cooperative agreements to 34 grantees throughout the United States.

The HepTLC initiative had two main components: (1) early identification and linkage to care of foreign-born people with HBV infection (i.e., in countries with HBsAg prevalence ≥2%) and (2) early identification and linkage to care of people with HCV infection. The latter was subdivided into three parts: (1) HCV testing in settings that provide services to people who inject drugs, (2) HCV services in community health centers, and (3) HCV testing and linkage to care in other settings.

CDC selected awardees through an objective review process based on organizational capacity, skill, and experience with the targeted population. In the HBV component, CDC funded nine projects to conduct HBV testing, including three state and local health departments, three universities, two community-based coalitions, and one community health center. Testing was conducted in more than 260 sites in 17 U.S. states (i.e., Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin); Washington, D.C.; and Puerto Rico. Testing sites included community outreach events, health centers, and community-based organizations (CBOs) that served foreign-born people from Asia and Africa. In the HCV component, four HIV prevention and education centers, four state and local health departments, one drug treatment center, and one university tested people who inject drugs. Testing sites included homeless shelters, syringe services programs, methadone clinics, alcohol and drug treatment centers, and correctional facilities. Seven community health centers provided services to populations with a large proportion of underserved and underinsured people born between 1945 and 1965 (i.e., baby boomers) and people who had ever injected drugs. Those funded in other settings (e.g., university hospitals, primary care centers, and public health clinics) provided HCV testing and care in venues prioritizing baby boomers. All grantees designed and implemented their testing and linkage-to-care programs independently.

CDC provided scientific and technical assistance to all projects, including access to educational materials and fact sheets from CDC's viral hepatitis education campaigns and training tools (i.e., hepatitis case studies and model medical curriculum). CDC also provided monitoring and guidance in the programs' development and evaluation. Additionally, CDC provided support for data collection, data entry or upload, and monthly report submission into EvaluationWeb®, the HepTLC data collection and management system.16

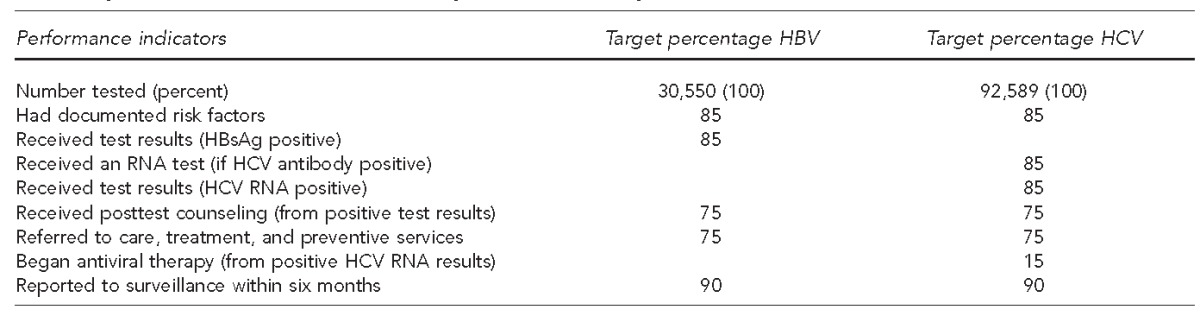

Each project was expected to conduct 1,000 to 4,000 HBV or HCV tests per year for a two-year period (September 2012 through September 2014). The number of expected tests depended on funding (e.g., some grantees received enough money to perform an expected 1,000 tests while others received enough money to perform an expected 4,000 tests) (Table). CDC set a combined testing goal of 123,139 people (30,550 HBsAg and 92,589 HCV antibody [anti-HCV] tests) for the HepTLC initiative.

Table.

Performance indicators and goals for HBV and HCV testing set by the Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care (HepTLC) initiative, United States, September 2012–September 2014a

The HepTLC initiative promoted viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, posttest counseling, and linkage to care at more than 260 sites in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington (DC), and Wisconsin.

HBV = hepatitis B virus

HCV = hepatitis C virus

HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen

RNA = ribonucleic acid

METHODS

Grantees entered data on patient demographics, testing, and linkage to care into EvaluationWeb.16 Patient demographics included birth year, race/ethnicity, sex, and health insurance status. Self-reported hepatitis B risk factors and exposures increasing the likelihood of chronic HBV infection included country of origin, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, identification as a man who has sex with men, household or sexual contact with someone known to be HBV infected, more than one sexual partner in the past six months, and injection drug use (ever or in the past 12 months). Self-reported hepatitis C risk factors and exposures included birth year (born between 1945 and 1965), HIV infection, currently on hemodialysis, injection drug use (ever or in the past 12 months), and having received a blood transfusion or clotting factors before 1992.

Performance indicators for HBV projects included the total number of people screened for HBV infection (i.e., the number of unique individuals screened for HBsAg) and those identified with HBV infection (i.e., the number of unique individuals who tested HBsAg positive on an initial or repeat HBsAg test). Performance indicators for HCV projects included the total number of people with anti-HCV-positive results (i.e., determined by the number of unique individuals with a positive [initial or repeat] anti-HCV test [i.e., rapid tests or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays]), those who received an HCV RNA test (i.e., the total number of individuals with a valid HCV RNA test date and valid HCV RNA qualitative or quantitative viral load ≥10 international units/milliliter [IU/mL] or result), and those identified with HCV infection (i.e., the total number of individuals with a valid HCV RNA qualitative/quantitative test date, and a positive qualitative HCV RNA test or quantitative HCV RNA viral load [≥10 IU/mL]).

RESULTS

A total of 87,860 people were tested for HBV or HCV infection (71% of the 123,139 testing goal).

HBV testing and linkage to care

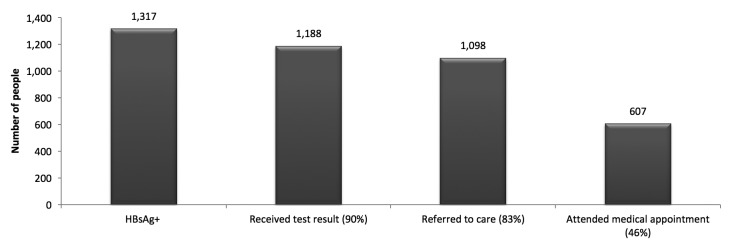

A total of 23,144 HBV (HBsAg) tests were conducted at more than 50 sites comprising primarily health-care settings and CBOs serving foreign-born people. Nearly two-thirds of people tested (n,14,407) were ≥40 years of age and 47% (n=10,859) were male. Among 19,883 people with known health insurance status, 7,441 (37%) reported having no health insurance. Of the 23,144 people tested, 19,805 (86%) originated from countries endemic for hepatitis B (i.e., HBsAg prevalence ≥2%); 13,230 (57%) originated from Asian/Pacific Island countries, 2,129 (9%) originated from African countries, 4,446 (19%) originated from other endemic countries, and 3,339 (14%) had missing data or originated from non-endemic countries. Among the 23,144 people tested, 1,317 (6%) were HBsAg positive, of whom 607 (46%) had a verified visit with a health-care provider (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HBV testing and linkage-to-care continuuma for the 23,144 people tested for hepatitis B surface antigen through the Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care (HepTLC) initiative, seven U.S. states, September 2012–September 2014b

aThe denominator for each result is the 1,317 people with a positive HBsAg.

bThe HepTLC initiative promoted viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, posttest counseling, and linkage to care at more than 260 U.S. sites. Sites that conducted HBV testing were located in California, Florida, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Oregon.

HBV = hepatitis B virus

HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen

HCV testing and linkage to care

A total of 64,716 people were tested for HCV (either anti-HCV and/or HCV RNA) at 206 venues. Of those tested, 14,884 (23%) were ≤30 years of age, 39,476 (61%) were male, 20,061 (31%) self-identified as non-Hispanic white, and 22,003 (34%) self-identified as non-Hispanic black. Among the 57,331 participants with known health insurance status, 32,866 (57%) reported having health insurance. One site conducted 7,146 HCV RNA tests without first obtaining an anti-HCV test during the testing period. All other projects initially conducted an anti-HCV test, per CDC recommendations.

During the initiative, 57,570 people were tested for anti-HCV (33,735 by rapid test and 23,835 by enzyme immunoassay [EIA]), of whom 7,580 (13%) were anti-HCV positive. Of the 7,580 people who tested anti-HCV positive, 4,756 (63%) were identified using rapid tests and 2,818 (37%) were identified using EIAs. (Test type was not available for six anti-HCV-positive people.) A total of 27,615 (48%) of those tested were born between 1945 and 1965, of whom 4,044 (15%) were anti-HCV positive. Among all people tested, 14,412 (25%) reported ever injecting drugs, of whom 4,651 (32%) were found to be anti-HCV positive.

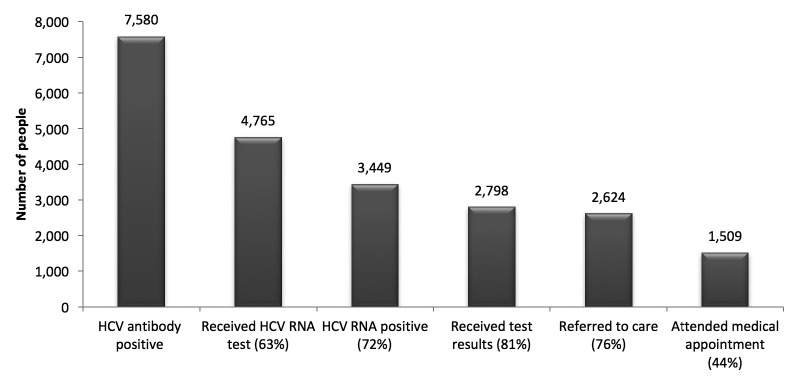

Of the 7,580 people who tested anti-HCV positive, 4,765 (63%) received an HCV RNA test (Figure 2). HCV RNA testing was much less frequent among people who had rapid anti-HCV testing. Of the 4,756 anti-HCV-positive people identified by rapid test, 2,340 (49%) were tested for HCV RNA. Of the 2,818 anti-HCV-positive people identified by EIA, 2,422 (86%) were tested for HCV RNA. Three individuals who tested positive for HCV RNA did not receive the initial anti-HCV test and were tested for HCV RNA only.

Figure 2.

HCV testing and linkage-to-care continuuma for the 57,570 people tested for HCV antibody through the Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care (HepTLC) initiative, 15 U.S. states/districts, September 2012–September 2014b

aThe denominator for each result is the 3,449 people with confirmed HCV infection.

bThe HepTLC initiative promoted viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, posttest counseling, and linkage to care at more than 260 U.S. sites. Sites for HCV testing were located in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maine, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, Washington (DC), and Wisconsin.

HCV = hepatitis C virus

RNA = ribonucleic acid

Of the 4,765 people who received an HCV RNA test, 3,449 (72%) had a positive HCV RNA test, of whom 2,798 (81%) received their test results, 2,624 (76%) were referred to medical care, and 1,509 (44%) had a verified visit with a primary care provider or liver specialist (Figure 2). About half of those tested had health insurance.

LESSONS LEARNED

Through participation in the HepTLC initiative, projects built their capacity to initiate or expand HBV or HCV testing and linkage to care among a variety of partner venues. The projects demonstrated that they could reach and test substantial numbers of people at risk for chronic viral hepatitis and identify previously unknown infections. We learned several lessons during project implementation. These observations often led to adjustments in project operations (e.g., increasing patient navigation access) that improved outcomes and can be instructive for other programs seeking to test people at risk for viral hepatitis infection and refer those with infection to care.

HBV testing and linkage to care

Education and testing were promoted to HBV-focused communities with large numbers of immigrants and refugees (principally from Asia and Africa). During implementation, employing staff members who were culturally and linguistically similar to the patients was a successful strategy to increase testing, provide test results and counseling, and link people with HBV infection to appropriate medical care. Promoting testing through community radio, newspapers, and cultural events facilitated programs' success in the continuity of care. These promotions addressed health literacy and cultural and community belief systems, including stigma associated with hepatitis B, and helped identify culturally and linguistically appropriate providers. Close collaboration among CBOs, community and refugee health centers, and other local clinical providers led to successfully linking patients to care. Additionally, dedicating resources to patient navigation was most effective in ensuring an initial visit, and translation services and insurance enrollment assistance were useful in supporting continuity of care.

HCV testing and linkage to care

Hepatitis C-focused venues succeeded in reaching at-risk populations by conducting anti-HCV testing. The proportion of anti-HCV-positive people was nearly 10 times the estimated prevalence among the U.S. population and more than four times the estimated anti-HCV prevalence among baby boomers (3.3%). Additionally, the projects were successful in identifying HCV infection, providing test results and posttest counseling, and referring individuals to medical care.

Among the various steps in the HCV care continuum, the two biggest challenges for these projects were ensuring HCV RNA testing for people with an anti-HCV-positive test result and linking people with confirmed HCV infection to care.

Projects using anti-HCV rapid test technology in community-based, nonclinical settings had the biggest challenges in assuring HCV RNA testing for people who were anti-HCV positive. EIA testing uses a venous blood specimen (i.e., residual serum can be used for HCV RNA testing if the specimen is anti-HCV positive), while rapid tests use a finger stick blood specimen, which requires a venous blood draw for HCV RNA testing if the rapid test result is positive. Most rapid anti-HCV tests were conducted at programs serving people who inject drugs and at nonclinical sites where skilled phlebotomy was not always available.

At testing sites where a phlebotomist was not available for immediate blood draw, anti-HCV-positive people needed to return for testing or accept referral to a different venue. Projects reported that anti-HCV-positive people often declined an additional test or were lost to follow-up. Community health centers and hospitals generally obtained venous blood samples for anti-HCV EIA testing and had the capacity for HCV RNA testing using the same specimen (i.e., reflex testing). Sites that provided onsite health care navigated people from HCV RNA testing to care and integrated services more successfully than sites that had to refer patients elsewhere.

Clinics or hospitals with integrated services for hepatitis C care facilitated the linkage process. People who actively injected drugs, were homeless, or did not have a permanent address appeared to benefit most from integrated services that met multiple needs in one location. CBO testing settings relied on referrals to health-care facilities or the individual's personal provider for follow-up medical care, and each additional step in the referral process presented another barrier to care. We were unable to assess initiation of antiviral therapy or continuity of hepatitis C-directed care. Anecdotally, some patients and providers chose to delay treatment until all-oral treatments became available.

The use of counselors and navigators helped ensure people could be contacted in the community and receive support to attend scheduled medical appointments. Navigators who knew the neighborhoods, spoke the language of targeted populations, could deliver culturally competent messages, and facilitated transportation to care facilities contributed to successfully linking patients to care. Successful patient navigation also required additional resources (e.g., staff funding).

Populations with the highest prevalence of undetected and untreated chronic viral hepatitis are also among the most medically underserved and challenging to reach. The HepTLC project demonstrated that it is possible to reach and test populations at the highest risk for chronic HBV and HCV infection, as evidenced by the high prevalence we found of each (6% HBsAg positivity and 13% anti-HCV positivity). Even in challenging circumstances, project personnel identified and informed many affected people and provided initial linkage to care. Such efforts required substantial investments in outreach and support services and in collaborating with CBOs and health-care providers. Research and evaluation efforts are needed to identify effective interventions to improve the rate of HCV RNA testing for people who are anti-HCV positive.

Although the HepTLC initiative was not designed to assess outcomes in care, CDC is assessing ways to improve hepatitis B and hepatitis C medical services beyond testing and referral to care. Opportunities available through the Affordable Care Act may increase access to care and treatment for underserved people with viral hepatitis.

Footnotes

The authors thank Jon Zibbell, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Division of Viral Hepatitis for editing this article.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC. All aspects of this project were considered part of a public health program and determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, et al. Recommendation for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu DJ, Xing J, Tohme RA, Liao Y, Pollack H, Ward JW, et al. -Hepatitis B testing and access to care among racial and ethnic minorities in selected communities across the United States, 2009–2010. Hepatology. 2013;58:856–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.26286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, Lu M, Teshale EH, Gordon SC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million persons with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1047–55. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmberg SD, Spradling PR, Moorman AC, Denniston MM. Hepatitis C in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, Lo Re V., 3rd The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Practice guidelines [cited 2014 May 15] Available from: http://www.aasld.org/practiceguidelines/documents/bookmarked%20practice%20 guidelines/chronic_hep_b_update_2009%208_24_2009.pdf.

- 9.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C [cited 2014 May 14] Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/full-report-view. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.National Research Council (US) Washington: National Academies Press; 2010. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis. 2011 [cited 2014 May 12] Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/hepatitis/actionplan_viralhepatitis2011.pdf.

- 12.Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Bell BP, Bice SD, Buffington J, Chamberland M, et al. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preventive Services Task Force (US) Rockville (MD): USPSTF; 2013. Hepatitis C: screening. Also available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshepc.htm [cited 2015 May 15] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preventive Services Task Force (US) Rockville (MD): USPSTF; 2014. Hepatitis B virus infection: screening, 2014. Also available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/page/topic/recommendation-summary/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014 [cited 2014 May 11] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Know More Hepatitis campaign materials [cited 2014 Mar 12] Available from: www.cdc.gov/knowmorehepatitis/materials.htm.

- 16.Luther Consulting, LLC. Carmel (IN): Luther Consulting, LLC; 2013. EvaluationWeb®: Version 5. [Google Scholar]