Abstract

In 2012, CDC issued recommendations calling for those born between 1945 and 1965, or baby boomers, to get tested for the hepatitis C virus. To help implement this recommendation, CDC developed “Know More Hepatitis,” a multimedia national education campaign. Guided by behavioral science theories and formative research, the campaign used multiple strategies to reach baby boomers and health-care providers with messages encouraging baby boomers to get tested for hepatitis C. With a limited campaign budget, the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign relied mostly on donated time and space from broadcast and print outlets. Donated placements totaled approximately $14.7 million, which reflected a more than 12-to-1 return on the campaign investment. This effort was supplemented with a small, paid digital advertising campaign. Combining audience impressions from both paid and donated campaign efforts resulted in more than 1.2 billion audience impressions.

An estimated 3.2 million Americans are living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection,1,2 and approximately 19,000 people die from HCV-associated liver cancer or chronic liver disease each year.2,3 People born between 1945 and 1965, or baby boomers, account for approximately 75% of all HCV infections and for an estimated 74% of HCV-associated deaths.3–6 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued recommendations in 2012 calling for one-time testing of people born between 1945 and 1965 for HCV infection.5 To help implement these recommendations, CDC developed “Know More Hepatitis,” a theory-driven, research-based, multimedia national education campaign, with the goal of increasing HCV testing among baby boomers.

PURPOSE

Target population

The “Know More Hepatitis” campaign had two distinct but complementary target audiences: people born between 1945 and 1965 and the primary care providers who cared for them. Although baby boomers comprise an estimated 27% of the U.S. population,5 they account for 75% of all HCV infections and are at greatest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and other HCV-related liver disease.4,5,7,8 Compared with other adults, baby boomers are five times more likely to have been infected with HCV.5 However, data show that about half of baby boomers who are infected with HCV are unaware of their infection.9,10 Consequently, primary care providers play a critical role in testing their baby boomer patients and linking those infected to lifesaving medical care and treatment.7,9–11 The “Know More Hepatitis” campaign developed strategies to reach both audiences.

Formative research

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine produced a report on hepatitis and liver cancer that indicated a lack of knowledge about chronic viral hepatitis and an insufficient understanding about the extent of the problem.12 In 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services developed the “Action Plan for the Prevention, Care, and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis,” which charged CDC with addressing the burden of chronic viral hepatitis in priority populations through a national direct-to-consumer communication campaign.13 In response to the charge, CDC initiated formative research efforts to further understand knowledge levels and identify key messages that would form the basis of the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign.

Literature reviews, surveys, market analyses, and qualitative research showed misinformation, misunderstandings, and myths about hepatitis C. For example, the national Healthstyles survey of consumers conducted in 2009 and 2010 indicated that approximately 70% of adults were either unsure or disagreed that they were “knowledgeable about viral hepatitis” (Unpublished data, Porter Novelli, 2009, 2010). This finding was corroborated by focus groups, which found that adults knew very little about hepatitis, the different types, and how the virus was transmitted, and even worried that the virus could be transmitted through the air.16 Even more troubling was the stigma associated with hepatitis C, with participants describing infected individuals as only those with “that kind of lifestyle,” such as alcohol or drug abusers, musicians, people with lots of tattoos, or prostitutes.14

To further inform development of the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign, CDC continued formative research activities from 2011 to 2014. Through 26 focus groups comprising 208 baby boomers representing diverse ethnicities, and conducted in six U.S. cities (i.e., Boston, Massachusetts; Charlotte, North Carolina; Chicago, Illinois; Denver, Colorado; Houston, Texas; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), CDC assessed overall knowledge and attitudes about hepatitis C and tested proposed messages for the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign (Unpublished data, CDC, Division of Viral Hepatitis, 2011–2014). Results indicated a lack of knowledge and awareness about hepatitis C and little understanding about the seriousness of the disease and its link to liver cancer. Messages that resonated with baby boomers tended to be very factual, supplying needed basic information about the virus, its effects and severity, and who was most affected by the disease (Unpublished data, CDC, Division of Viral Hepatitis, 2011–2014).

To better understand how to enhance HCV testing of baby boomers, CDC also conducted qualitative research among primary care physicians in 2012 and 2013 (Unpublished data, CDC, Division of Viral Hepatitis, 2011–2014). Through telephone focus groups, CDC explored physicians' attitudes about CDC's 2012 HCV testing recommendation, reasons for or against screening patients, and reactions to rationale supporting the recommendation.5 One year later, almost every physician participant in the 2013 groups reported awareness of the recommendation, although reported uptake of the recommendation was mixed. Some participants said they were testing their baby boomer patients, while others stated they would continue to test for HCV based solely on medical indications and behavioral risk factors. Although physicians found the published rationale behind the recommendation to be compelling, many physicians said they would not change their HCV testing practices to include testing people based solely on birth year. As with the consumer groups, physicians had unfounded beliefs about hepatitis C (e.g., hepatitis C was not an issue for their patient population or in their area of the country). Physicians in the groups suggested, without solicitation, that a direct-to-consumer campaign would encourage patients to request testing and help physicians talk about HCV testing with their patients. Informed by the qualitative research findings, CDC developed educational materials and trainings directed toward providers (Unpublished data, CDC, Division of Viral Hepatitis, 2011–2014).

METHODS

Laying the groundwork with basic consumer education

CDC began laying the groundwork for the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign more than a year prior to launching in 2012. Because formative research findings indicated low consumer knowledge, a direct-to-consumer campaign was needed with the goal of educating the public about hepatitis C and providing a call to action for testing. CDC used several communication strategies to reach consumers, including news media outreach; digital, broadcast, and print media; and social media.

Consumer campaign messages and materials

With the release of HCV testing guidelines in 2012, CDC launched the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign and added a prominent main message: “CDC recommends that anyone born between 1945 and 1965 get tested for hepatitis C.” Messages also highlighted the high prevalence of HCV infection among baby boomers and that, if left untreated, HCV infection could lead to liver cancer (Figure). Because the campaign's formative research indicated a need for basic education, some campaign materials continued to relay general facts about hepatitis C. Other campaign materials attempted to dispel commonly held myths, such as “only those kind of people” get infected or that people would know they were infected with HCV because “they would have symptoms.”

Figure.

Print advertisement and poster from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's “Know More Hepatitis” education campaign,a United States, 2012

a“Know More Hepatitis” is a multimedia national education campaign that used multiple strategies to reach baby boomers (i.e., those born between 1945 and 1965) and health-care providers with messages encouraging baby boomers to get tested.

Broadcast materials included video and radio public service announcements (PSAs) explaining basic facts about hepatitis C and encouraging baby boomers to get tested. Materials containing the aforementioned messages were rendered in a variety of formats, including digital buttons, badges, and banner advertisements; infographics; magazine and newspaper advertisements; printed posters; and out-of-home advertisements (e.g., billboards and airport dioramas). CDC developed the “Know More Hepatitis” website15 to provide detailed information on hepatitis C and baby boomers, answer frequently asked questions, and house campaign materials. To support interpersonal communication between health professionals and their patients, CDC also created a one-page fact sheet highlighting why baby boomers should get tested.16

Consumer implementation strategies

CDC implemented the consumer component of the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign using broadcast, out-of-home, digital, print, news media, and social media strategies. CDC also distributed campaign materials to media outlets nationwide, but, given the limited campaign budget, relied heavily on donated time and space. The donated television, radio, and out-of-home advertisement placements were supplemented with a small, paid digital advertising effort that microtargeted baby boomers using YouTube and Google display advertisement platforms. The YouTube advertisement component involved placing the video PSA before content baby boomers wanted to view (e.g., a clip from the evening news). The Google display advertisement component used banner advertisements promoting HCV testing for people born between 1945 and 1965. When viewers clicked on the advertisement, they were taken to the “Know More Hepatitis” website. CDC also distributed the infographic and matte, or pre-produced articles, to news media outlets that donated print and online placements around the country. Finally, with baby boomers' social media usage increasing,17 CDC used channels such as Facebook and Twitter to supplement the campaign's other strategies and help spread the word to consumers and partners.

To extend the campaign's reach, CDC also relied on state and local public health agencies and community-based groups to help disseminate campaign materials. CDC offered all materials in electronic or downloadable formats through the campaign website and encouraged their widespread use through social media posting, electronic dissemination, or local printing. To broaden use of the campaign materials, CDC encouraged state and local health departments to customize materials with their own information, which allowed campaign messages to spread further.

Primary care providers: educational materials and implementation strategies

To reach primary care providers and other health professionals, CDC used a variety of strategies and communication outlets. When Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report first published the HCV recommendation in 2012,5 CDC disseminated the information via e-mail updates, clinical news announcements, social media, medical and professional news outlets, and the CDC website. CDC developed and delivered trainings and presentations at professional conferences and meetings. CDC also worked with online medical education partners, including Medscape and QuantiaMD, to educate health professionals about CDC's HCV testing recommendation.

To broaden the effort, CDC developed educational materials and clinical tools and posted them on its website. Web content and educational summary sheets explained the HCV testing recommendation, the rationale behind its development, and the benefits that could be achieved from its adoption. Clinical tools included a testing algorithm and interpretation chart to assist in HCV testing. CDC also hosted a Public Health Grand Rounds18 on hepatitis C and participated in the HCV Prevention and Cure Summit in 2014.19 Both events addressed the recommendation, rationale, and importance of full implementation to reduce morbidity and mortality. Both events were also broadcast online and available worldwide.

Finally, CDC funded two medical and public health academic centers to further HCV education. One institution developed a comprehensive online HCV training program for practicing clinicians20 and the other developed an HCV curriculum for use in medical schools.21

OUTCOMES

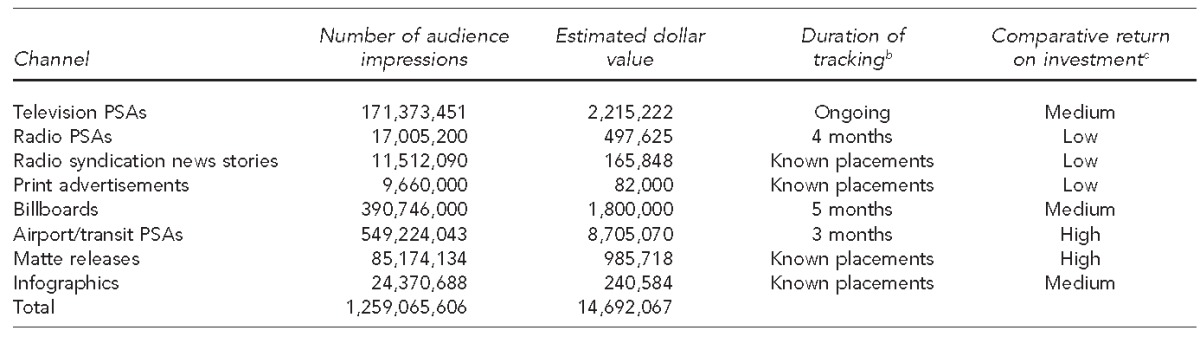

Since its launch, the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign has achieved more than 1.2 billion documented audience impressions, a standard media measurement for the number of times the material was displayed or broadcast. This audience reach resulted from donated placements, estimated to be worth more than $14.7 million, which occurred in several media outlets. The $1 million investment in the campaign, compared with the achieved media value, represented an estimated 12-to-1 return on the campaign's initial investment.

With a small paid outreach effort, CDC Google display advertisements achieved an average 0.40% click rate, which was higher than the industry standard of 0.09%.22 This effort generated approximately 26.5 million impressions and more than 200,000 visits to the “Know More Hepatitis” website. Additionally, the YouTube advertisements generated more than 1.6 million campaign PSA views, which resulted in the PSA being the third most-watched video on CDC's YouTube Channel during the time of the advertisement buy.

LESSONS LEARNED

Launching and implementing any national education campaign has many challenges. One such challenge the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign faced was overcoming the misinformation and stigma surrounding the disease. The consumer target audience had limited understanding and awareness about hepatitis C. Increasing the perceived importance of HCV testing for baby boomers requires an ongoing and concerted effort. Attitudes do not change quickly, and ongoing education is needed to reach the target audience.

Unfortunately, we learned that media outlets vary in the duration and precision of tracking donated space and time. For example, CDC's vendor for transit advertisements and airport dioramas supplied tracking data for only three months. However, individuals reported seeing the campaign advertisements in those outlets more than a year later. As a result, reporting or comparing audience reach and value across the various channels was difficult. In an attempt to compare relative return on investment, we standardized and compared tracking data (Table).

Table.

Comparative return on investment by media channel for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's “Know More Hepatitis” education campaign,a United States, 2012

“Know More Hepatitis” is a multimedia national education campaign that used multiple strategies to reach baby boomers (i.e., those born between 1945 and 1965) and health-care providers with messages encouraging baby boomers to get tested.

bTracking periods vary by channel and distribution vendor. Known placements refer to actual stories or advertisements and their corresponding reach and value.

cComparative return on investment is calculated based on standardizing known reporting periods compared with investments for production and distribution costs.

PSA = public service announcement

Selecting which channels to pay for placements with a limited budget was another challenge. Paying for traditional media would jeopardize donated placement, as media outlets typically do not donate space if paid placements have been obtained. Digital media channels have no donations for public services, so CDC used a small advertisement buy on both Google and YouTube. The reality for any paid media placement is that the audience reach is directly related to the ability to pay for placements. The performance of these advertisements indicate that CDC reached a proportion of baby boomers and encouraged them to click on the banner advertisement to learn more.

CDC also recognized that further ensuring the campaign's reach required a dedicated component that targeted health-care professionals. The “Know More Hepatitis” campaign provided information and rationale on the HCV baby boomer screening recommendation and how providers could incorporate the recommendation into their practice. If campaign messages to consumers urged them to talk to their doctor about getting tested, then providers needed to be ready and willing to discuss the testing recommendations with their patients. CDC is committed to informing providers about the importance of testing baby boomers and facilitating medical care for those who are infected.

CONCLUSIONS

The “Know More Hepatitis” campaign was one component of CDC's overall effort to decrease HCV-associated morbidity and mortality by testing individuals for hepatitis C and linking those infected to medical care. Although the campaign had widespread success, as indicated by available process measures, many more opportunities and challenges lay ahead in the fight against hepatitis C. With new treatments that offer a cure for many of those infected, it is critical that CDC sustain and increase educational efforts.23 CDC is committed to expanding its programs and sustaining the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign as one of the most public-facing aspects of the collective response. The efforts described in this article are ongoing, and future reports will describe how this national campaign may have contributed to increased testing for hepatitis C infection.

Footnotes

All aspects of the “Know More Hepatitis” campaign were considered part of a public health program and determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2014. Viral hepatitis surveillance, United States—2012. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2012surveillance/index.htm [cited 2014 Sep 3] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Holmberg SD. Causes of death and characteristics of decedents with viral hepatitis, United States, 2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:40–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moorman AC, Gordon SC, Rupp LB, Spradling PR, Teshale EH, Lu M, et al. Baseline characteristics and mortality among people in care for chronic viral hepatitis: the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:40–50. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngo-Metzger Q, Ward JW, Valdiserri RO. Expanded hepatitis C virus screening recommendations promote opportunities for care and cure. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:364–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rein DB, Smith BD, Wittenborn JS, Lesesne SB, Wagner LD, Roblin DW, et al. The cost-effectiveness of birth-cohort screening for hepatitis C antibody in U.S. primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:263–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu F, Tong X, Leidner AJ. Hospitalizations and costs associated with hepatitis C and advanced liver disease continue to increase. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1728–35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmberg SD, Spradling PR, Moorman AC, Denniston MM. Hepatitis C in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volk ML, Tocco R, Saini S, Lok AS. Public health impact of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;50:1750–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litwin AH, Smith BD, Drainoni ML, McKee D, Gifford AL, Koppelman E, et al. Primary care-based interventions are associated with increases in hepatitis C virus testing for patients at risk. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Research Council (US) Washington: National Academies Press; 2010. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Washington: HHS; 2014. Action plan for the prevention, care, and treatment of viral hepatitis: updated, 2014–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen CM, Carnes CA. Lessons learned from exploratory research about viral hepatitis. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:364–9. doi: 10.1177/1524839912455643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Know more hepatitis [cited 2014 Sep 15] Available from: www.cdc.gov/knowmorehepatitis.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Hepatitis C: why baby boomers should get tested [cited 2014 Sep 15] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/knowmorehepatitis/media/PDFs/factsheet-boomers.pdf.

- 17.Pew Research Center. Social networking fact sheet [cited 2014 Sep 10] Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) The 25th anniversary of the discovery of the hepatitis C virus: looking back to look forward [cited 2014 Aug 12] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2014/june2014.htm.

- 19.Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. 2014 National Summit on HCV Prevention and Cure [cited 2014 Aug 12] Available from: http://www.viralhepatitisaction.org/2014-national-summit-hcv-prevention-and-cure.

- 20.University of Washington. Hepatitis C online [cited 2014 Aug 12] Available from: http://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu.

- 21.University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health. KnowHepatitis.org: clinical training [cited 2014 Aug 12] Available from: http://knowhepatitis.org/clinicaltraining.

- 22.Google. Display benchmarks [cited 2014 Oct 1] Available from: http://www.richmediagallery.com/resources/benchmarks.

- 23.Fox AN, Jacobson IM. Recent successes and noteworthy future prospects in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 1):S16–24. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]