Abstract

Objective

An estimated 2.7–3.9 million Americans are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). Despite being the most common blood-borne virus in the United States, routine HCV testing is not commonly practiced. To address this gap, we measured the impact of integrated routine HCV testing on patient care.

Methods

As part of CDC's Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care initiative, which promoted viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, posttest counseling, and linkage to care at 34 U.S. sites, National Nursing Centers Consortium integrated a routine opt-out HCV testing and linkage-to-care model at five federally qualified health centers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from October 1, 2012, to June 30, 2014. The model included medical assistant-initiated testing, reflex laboratory-based HCV tests, and electronic health record modifications to prompt, track, and facilitate reimbursement for tests performed on uninsured patients.

Results

During the study period, 4,207 unique patients received HCV antibody (anti-HCV) testing, of whom 488 (11.6%) tested anti-HCV positive. Of those testing positive, 433 (88.7%) received a confirmatory HCV RNA test; of these 433 recipients, 313 (72.3%) were diagnosed with current infection (overall prevalence = 7.4%), of which 243 (77.6%) received their HCV RNA-positive results, 184 (58.8%) were referred to an HCV care provider, and 121 (38.7%) were linked to care. The highest rates of current infection were among non-Hispanic white patients (18.1%, 90/496); patients from the Public Health Management Corporation Care Clinic, which treats HIV and HCV patients on-site (14.3%, 200/1,394); and patients aged 50–69 years (10.7%, 189/1,767).

Conclusion

Our model successfully integrated HCV testing and linkage to care into routine primary care. This study also identified potential successes and barriers that may be experienced by other primary care health centers that are integrating HCV testing.

In the United States, approximately 2.7–3.9 million people are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV).1,2 Reports show that the majority of those infected are unaware of their diagnosis and that infected people are diagnosed late—after decades of infection once they have developed HCV-associated complications.1,3–5 HCV is the most common blood-borne virus and a leading cause of chronic liver disease (i.e., hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation). In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released recommendations for one-time HCV testing for all individuals born between 1945 and 1965, or baby boomers.1,5–8 HCV-associated morbidity and mortality rates are projected to increase as HCV-infected baby boomers age.9,10 Annual direct costs associated with HCV already total $1.1 billion, and annual indirect costs total $7.5 billion.11,12 Because so many infected people remain unaware of their status, annual direct spending is expected to exceed $10.7 billion between 2010 and 2019.12,13

To detect active HCV infection, two tests are required. The HCV antibody (anti-HCV) test determines if someone has been exposed to the virus, while the confirmatory test detects the presence of HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) and definitively identifies people with current (i.e., active) disease.7 Of individuals who are exposed to HCV, an estimated 15%–25% will clear the virus on their own, while 75%–85% will develop chronic infection.5 People with chronic infection require regular medical evaluation by an HCV care provider, including a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, or primary care provider trained to treat HCV.7

HCV disproportionately affects certain subpopulations, including baby boomers, people with a history of incarceration, individuals living in households with annual incomes <$25,000, people with less than a high school education, and homeless people.8,14,15 Although the most common identified risk factor is intranasal or injection drug use (IDU), up to 45% of infected people have no knowledge of how they contracted the virus.8

Routine testing is not commonly integrated into primary care. In a 2014 study, primary care providers from four large health networks were interviewed to assess their perspectives on HCV testing.9 The study found that most providers had not implemented the recommendations because of the time required to gather patient risk-factor history; the need to discuss stigmatized behaviors; the concern that health insurance would not adequately cover HCV testing or treatment; and the worry that appropriate support for patients lacking access to HCV care, medical evaluation, and treatment would not be available.9 However, testing in primary care settings offers many benefits, including the use of reflex laboratory-based testing (i.e., a laboratory test performed subsequent to an initially ordered and resulted test), disclosure of test results by a known and trusted medical provider, and integrated support services that help patients transition from primary to HCV care.

As part of CDC's 2012 Hepatitis Testing and Linkage to Care initiative, which promoted viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, posttest counseling, and linkage to care at 34 U.S. sites, National Nursing Centers Consortium—a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania-based national membership organization that promotes nurse-led care through technical assistance, policy, and program management—integrated routine HCV testing and linkage to care at five federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in Philadelphia. They integrated testing and linkage to care by modifying the shared electronic health record (EHR) and clinic policies and by increasing health center staff member awareness of HCV testing recommendations. We aimed to demonstrate that an integrated testing and intensive linkage-to-care model could increase rates of testing, disease detection, and linkage to care.

METHODS

In October 2012, National Nursing Centers Consortium partnered with its parent company, Public Health Management Corporation (PHMC), a public health institute, to implement routine HCV testing and linkage to care in PHMC's five FQHCs:16 Mary Howard Health Center, PHMC Care Clinic, PHMC Health Connection, Rising Sun Health Center, and Congreso Health Center.13 Each health center serves at-risk populations, including the homeless and underserved. In addition to primary care, two health centers offer specialized health services: Congreso Health Center treats patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on-site, and PHMC Care Clinic treats both mono-infected HCV and HIV patients and coinfected patients on-site.

To integrate testing, the health centers adopted a medical assistant-initiated, opt-out, laboratory-based testing model through staff member training, clinic flow analysis, and modifications to the shared EHR.16 Three steps prior to testing implementation included (1) training to educate health center staff members about HCV etiology and epidemiology, as well as project goals and model implementation plan; (2) negotiating with commercial laboratories that were paid with grant funding on pricing for HCV tests performed on uninsured patients; (3) and deciding if universal or risk-based HCV testing was the most efficient testing method.

Health centers serving patients at high risk for HCV (i.e., Mary Howard Health Center and PHMC Care Clinic) conducted universal testing, and health centers serving patients at low risk for HCV (i.e., Rising Sun Health Center, PHMC Health Connection, and Congreso Health Center) conducted testing on patients at high risk for HCV. HCV testing eligibility included the following risk factors: patients born between 1945 and 1965; history of intranasal or IDU; individuals who reported having received a tattoo or piercing from an unlicensed location; recipients of a blood transfusion/organ transplant before 1994; women who had a cesarean section before 1990; individuals on long-term hemodialysis; people with a liver condition; individuals with a work exposure to infected blood; HIV-positive patients without an HCV test in their medical chart; and patients who were presently or previously homeless.

Risk was determined by the percentage of clinic patients who met at least one of the HCV testing eligibility criteria. For example, all patients seen at Mary Howard Health Center had experienced homelessness and were eligible for testing. Similarly, PHMC Care Clinic serves baby boomers, patients with a history of intranasal or IDU, patients who have experienced homelessness, or patients who are HIV-positive. Universal HCV testing at these sites best fit the patient population and did not add unnecessary work for health center staff members.

Unlike Mary Howard Health Center and PHMC Care Clinic, PHMC Health Connection and Rising Sun Health Center have a younger patient population who typically lives in nearby public housing complexes, and patients do not report a history of hard drug use or homelessness. Congreso Health Center provides care for HIV-positive patients, many of whom report an intranasal or IDU history, but they also serve a large number of women and their children. If patients were universally tested at Congreso Health Center, many patients who did not have a reported risk factor would be unnecessarily testing based on the HCV testing eligibility criteria. Instead, medical assistants asked patients at these sites if they had any of the aforementioned risk factors while taking vital signs prior to the medical appointment.

Using an opt-out model, medical assistants informed eligible patients that they would be tested for HCV unless they declined.16,17 Standing orders allowed medical assistants to begin the laboratory requisition for the existing U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved anti-HCV test with reflex HCV RNA quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction test (RealTime HCV/m2000sp/2000rt, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois; and COBAS® AMPLICOR HCV Test, Version 2.0, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana) on all patients who accepted HCV testing. Reflex testing technology allows the laboratory to perform the confirmatory HCV RNA test on the same specimen that tested anti-HCV positive, thereby eliminating the need for a second specimen. We defined patients with a negative anti-HCV test result as lacking HCV infection. We defined a positive anti-HCV test and negative HCV RNA test as HCV exposure but not having current HCV infection. We defined patients with both positive anti-HCV and HCV RNA tests as having current HCV infection and requiring follow-up care.

Laboratories electronically uploaded confirmed HCV test results into the patient's medical chart. Abnormal tests were highlighted in red, alerting clinic staff members to schedule a follow-up appointment. At the follow-up appointment, providers disclosed the positive result and educated patients about their disease, including the actions required to preserve their liver health. EHR modifications to support the program included two types of automatic reminders (i.e., one for testing eligibility and one for linkage services), templates to collect discrete data, monthly data reporting, and weekly summary reports. Weekly reports and customized data extraction reports were used for program research and evaluation. Lastly, an account for the HCV tests performed on uninsured patients was added to the laboratory requisition.16 In September 2013, a linkage-to-care coordinator was hired to oversee patient engagement in HCV care.

We present HCV testing and linkage-to-care data from the 21-month study period, from October 1, 2012, to June 30, 2014. We extracted data presented in this article from the shared EHR, Allscripts Professional, and analyzed the data using SAS® version 9.3.18,19

RESULTS

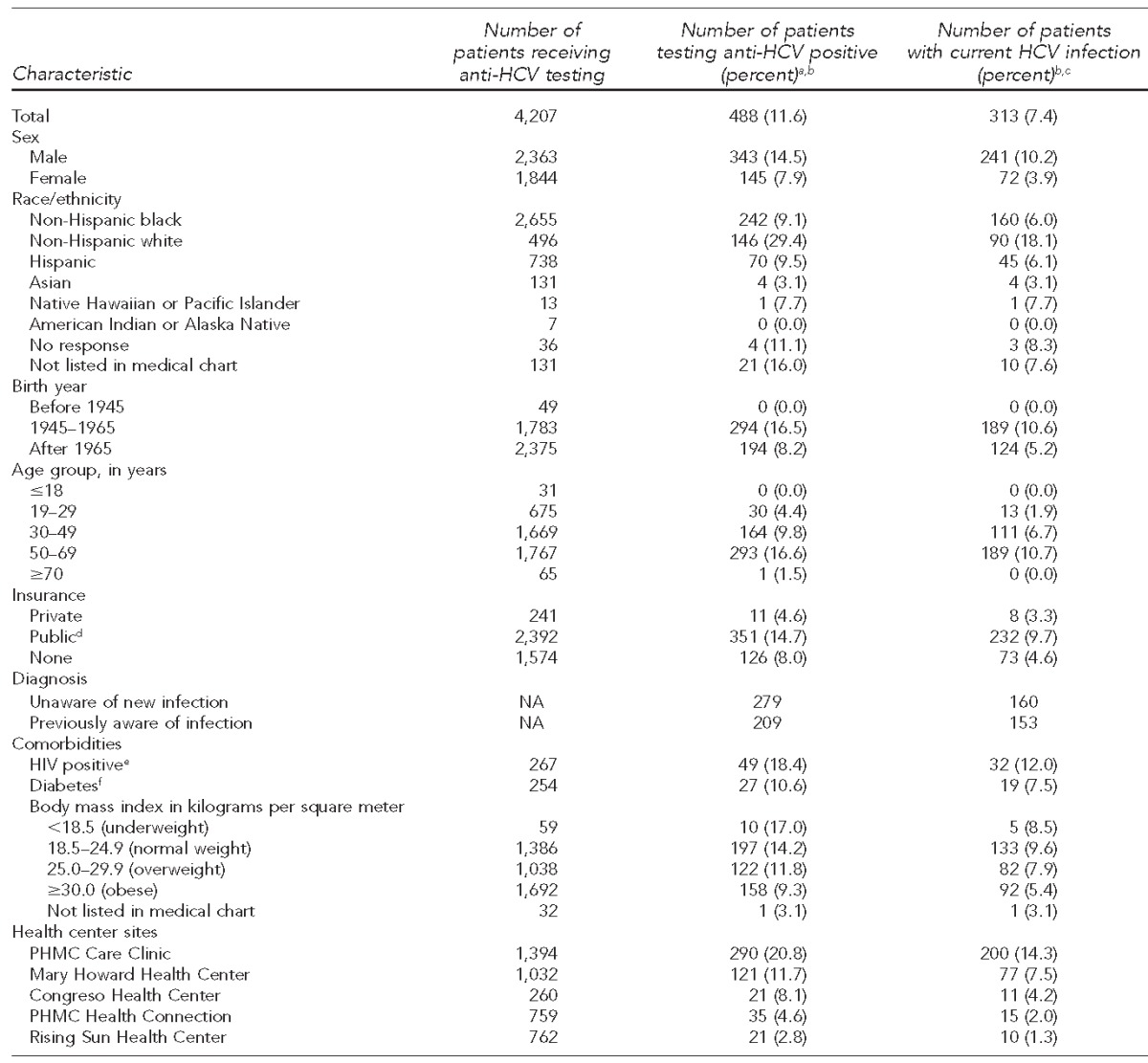

During the study period, 4,207 anti-HCV tests were performed at the five FQHCs, of which 488 (11.6%) were anti-HCV positive and 313 (7.4%) were HCV RNA positive. Those who self-identified as non-Hispanic black, men, those aged 50–69 years, and individuals with public health insurance were tested most frequently and had the highest number of positive HCV tests compared with other groups. Health centers conducting universal HCV tests (i.e., PHMC Care Clinic and Mary Howard Health Center) performed more HCV tests than the health centers performing targeted risk-based testing. The highest rates of current infection were among patients aged 50–69 years (10.7%, 189/1,767), patients of the PHMC Care Clinic (14.3%, 200/1,394), and those who self-identified as non-Hispanic white (18.1%, 90/496) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and seroprevalence of patients who received anti-HCV testing, tested anti-HCV positive, and are currently infected with HCV at five federally qualified health centers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 2012–June 2014

aDenotes a positive anti-HCV test without HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) test performed

bPercentages are row percentages.

cDenotes a positive anti-HCV test and positive HCV RNA test

dPublic insurance is defined as Medicaid, Medicare, or Medicaid-managed plan.

eCalculated using the number of patients who had an HIV test

fCalculated using the number of patients whose diabetes status was listed in their medical chart

anti-HCV = hepatitis C virus antibody

HCV = hepatitis C virus

NA = not applicable

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

PHMC = Public Health Management Corporation

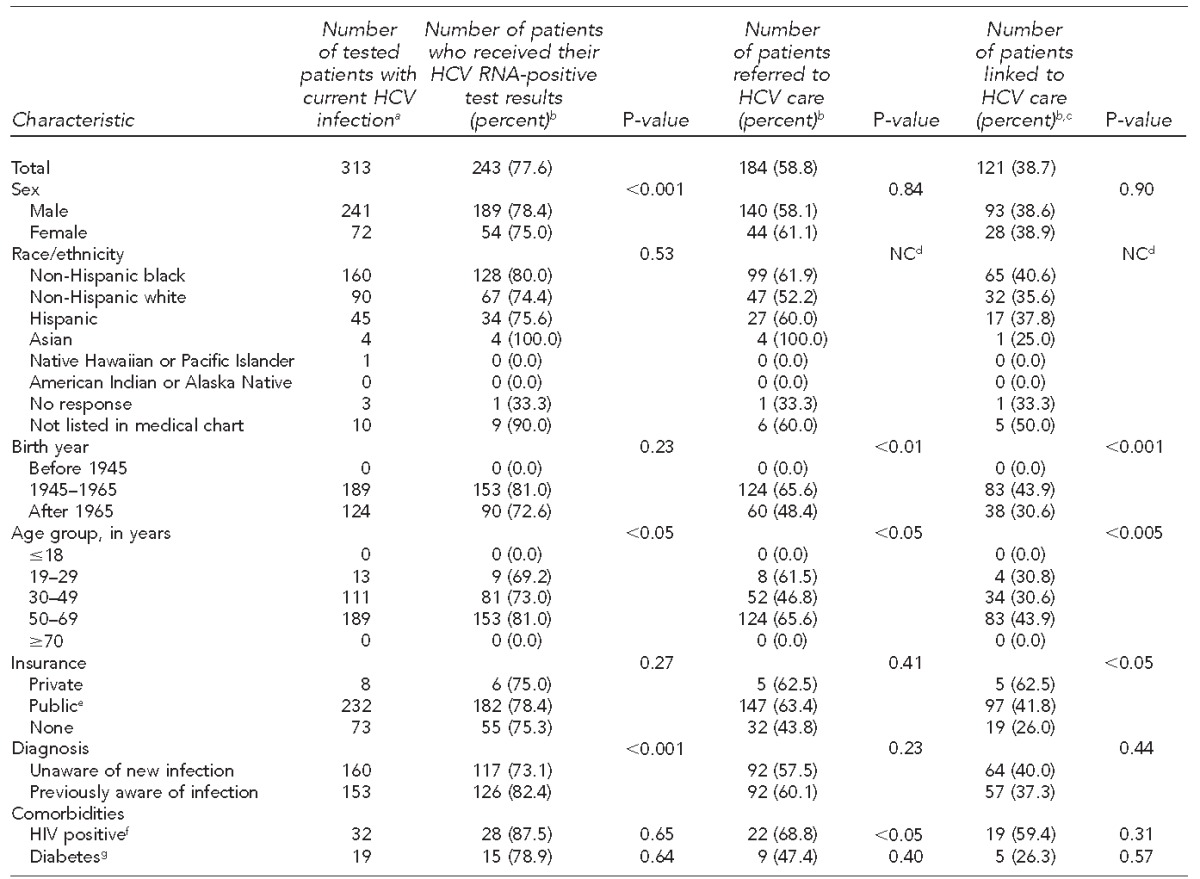

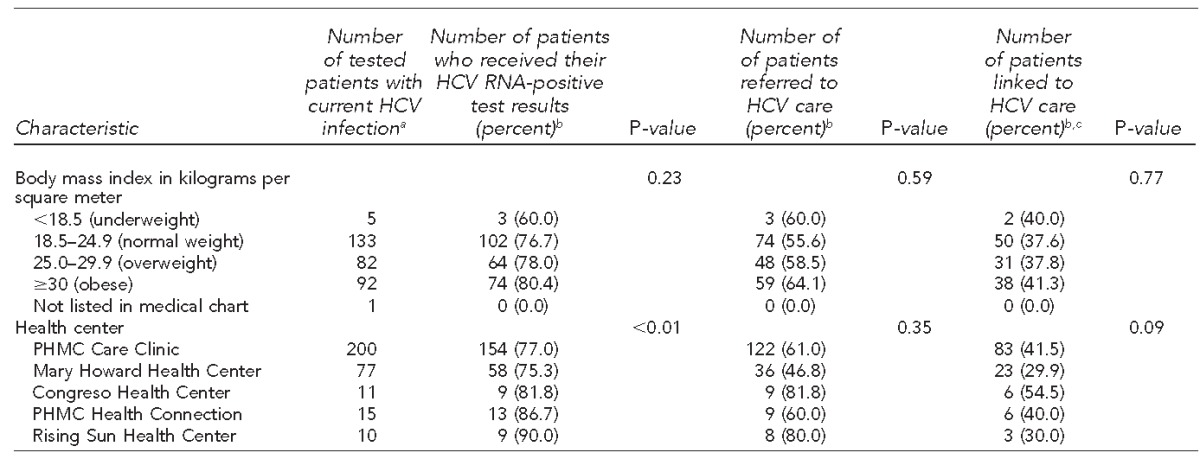

Of the 488 anti-HCV-positive patients, 433 (88.7%) received a confirmatory HCV RNA test, of whom 313 (72.3%) tested positive for HCV RNA (overall prevalence = 7.4%). Of the 313 patients with current HCV infection, 243 (77.6%) received their diagnosis, 184 (58.8%) were referred to an HCV care provider, and 121 (38.7%) were medically evaluated by the referred provider. Coinfected patients had higher linkage-to-care rates than mono-infected HCV patients: Of the 32 people with HIV who tested positive for anti-HCV, 28 (87.5%) received their HCV RNA-positive result, 22 (68.8%) were referred to an HCV care provider, and 19 (59.4%) were evaluated by the referred provider. Those born between 1945 and 1965 also had a high rate of medical evaluation once referred to an HCV care provider (43.9%, 83/189). The lowest linkage-to-care rate was for uninsured patients (26.0%, 19/73). Only sex and prior knowledge of HCV status (p<0.001) were significant predictors of chronic HCV infection. Birth year was the only significant predictor of a person being referred to an HCV care provider (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with current HCV infection who received their results and were linked to care at five federally qualified health centers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 2012–June 2014

aDenotes positive HCV antibody test and positive HCV RNA test

bPercentages are row percentages.

cDefined as attending at least one appointment with a primary care provider from PHMC Care Clinic or hepatologist or gastroenterologist at a local academic medical center

dCounts were too small to calculate p-values.

ePublic insurance is defined as Medicaid, Medicare, or Medicaid-managed plan.

fCalculated using the number of patients who had an HIV test

gCalculated using the number of patients who had diabetes status listed in their medical chart

HCV = hepatitis C virus

RNA = ribonucleic acid

NC = not calculated

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

PHMC = Public Health Management Corporation

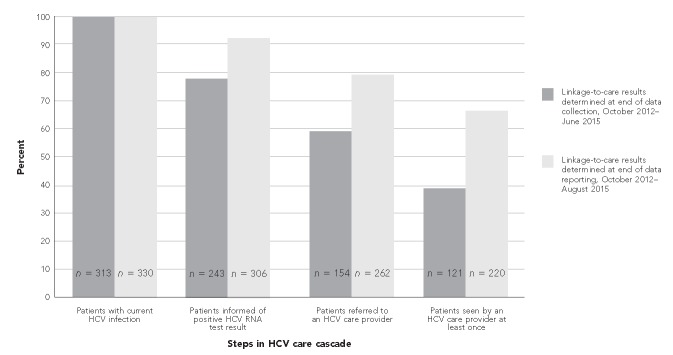

Data collection for this study ended June 30, 2015, but analysis did not end until August 15, 2015. During that time, the number of anti-HCV-positive patients who received confirmatory testing increased from 433 of 488 (88.7%) to 451 of 488 (92.4%), and another 17 patients were identified as currently infected with HCV. Of the 330 HCV-infected patients, 306 (92.7%) were told their results, 262 (79.4%) were referred to an HCV care provider, and 220 (66.7%) received a medical evaluation. Comparing the linkage-to-care cascades during data collection with the end of data analysis shows an improvement in linkage-to-care rates (Figure). Finally, of the 330 infected patients, 24 (7.3%) had initiated treatment and 15 (4.5%) had achieved sustained virologic response (i.e., eradication of HCV infection).

Figure.

Comparison of linkage-to-care cascade for patients identified with current HCV infection and showing improvement in linkage-to-care rates at five federally qualified health centers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 2012–June 2015a

aSites included Mary Howard Health Center, Public Health Management Corporation (PHMC) Care Clinic, PHMC Health Connection, Rising Sun Health Center, and Congreso Health Center.

HCV = hepatitis C virus

RNA = ribonucleic acid

DISCUSSION

This integrated routine HCV testing model provides a successful example of scaling up HCV testing and linkage to care. Through the model, a large number of HCV-positive patients were identified, made aware of their current HCV status, and linked to care. Results also confirmed that testing in FQHCs is an important way to identify large numbers of people previously undiagnosed with HCV.

Although non-Hispanic black patients were tested more frequently and had a larger number of positive results than patients in other racial/ethnic groups, their rate of current disease (6.0%) was substantially lower than that of non-Hispanic white patients (18.1%). In Philadelphia, non-Hispanic black people are disproportionately affected by HCV infection; however, higher rates of infection among non-Hispanic white individuals occur in other U.S. areas, with increased IDU as the most common risk factor for HCV infection.14,20,21

Our data also showed high linkage-to-care rates among HIV-positive patients. These patients were primarily from PHMC Care Clinic, which treats mono-infected and coinfected HCV and HIV patients. Patients are seen frequently as part of routine HIV care, allowing more opportunities for providers to monitor HCV.

As more effective and tolerable treatments are made available, routine screenings and improved linkage to care have become increasingly important to improve individual and public health. However, studies have identified gaps in HCV care. A 2014 meta-analysis found that of the estimated 3.5 million individuals with current HCV infection, 43% had access to outpatient health care, 27% were confirmed through HCV RNA testing, and 16% had started HCV treatment.22 Surveillance data captured by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health from 2010 to 2013 showed that of 47,525 individuals with positive anti-HCV tests, 6,383 of 13,596 (47%) people aware of their exposure had a positive confirmatory HCV RNA test, indicating current infection. Of those 6,383 people with current infection, 1,745 (27%) were in medical care and 956 (15%) had received or were undergoing HCV treatment.23

Our linkage-to-care results exceeded those seen in Philadelphia and nationally, likely because of testing in a primary care setting, intensive linkage services, and enhanced patient tracking.22,23 Patients tested in primary care are already in a trusted health-care setting where they can easily speak with their primary care provider and link into HCV care for medical evaluation. Intensive care management and patient navigation also enabled patients to be tracked through care and offered aid when necessary. For example, our coordinator found that some patients living in shelters needed to be signed out and escorted to their HCV-related appointments. Similar findings about the importance of intensive linkage services were seen in a Philadelphia community-based HCV testing and linkage-to-care program.24

Additionally, project staff members are working with specialist offices at local academic medical centers to improve feedback to referring providers, who were not notified if patients attended HCV care appointments or consultations from the visit. This increased communication has improved the continuity of patient care because primary care providers are more aware of missed appointments.

Although a large proportion of patients found to be currently infected were successfully linked to HCV care, the number of patients starting HCV treatment was low. This finding is not uncommon. Payers have made it increasingly difficult to get prior authorization to treat patients because of the prohibitively high cost of HCV medications, which has delayed treatment.25 The complicated prior authorization process did not cause a delay in patients getting referred to off-site HCV care providers, but it did prevent more PHMC Care Clinic patients from starting treatment during the study period.

In March 2015, a dedicated staff member—the HCV treatment coordinator—was assigned to the project to increase the number of patients treated at PHMC Care Clinic. This individual submits paperwork to insurance companies, lists missing or expired laboratory tests required by each insurance company, and notifies providers of the tests that need to be drawn. The HCV treatment coordinator also tracks medication refills and clinical outcomes. Additionally, a welcome packet for patients who want to pursue HCV treatment has been developed to educate patients on what to expect throughout the process, including typical timelines.

New EHR modifications to facilitate the prior authorization process have also been made. One modification includes a results summary template that shows the laboratory test date and result for tests required by all insurance companies and a custom folder that lists the required tests for insurance companies. When the folder is selected, the requisition will prepopulate with the necessary International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes. These modifications help staff members to quickly identify missing or expired tests and eliminate the need to remember which tests insurance companies require.

As the project has progressed, three adjustments have been made to promote testing and improve clinic protocols. The first was adding the linkage-to-care coordinator in September 2013. Simultaneously, health centers implemented routine HIV testing.16 Bundling HCV and HIV tests resulted in a 52.7% (942/1,786) increase in HCV tests performed between the 11 months before (1,786 tests performed) and after (2,728 tests performed) dual HCV/HIV testing started.16,17 As of June 2014, all health centers have adopted universal testing; today, only patients ≥18 years of age without a previous HCV diagnosis are eligible for testing. Patients are subsequently tested based on reported risk factors, such as incarceration, housing changes, drug use, and new tattoos or piercings from unlicensed locations. To help support this transition and ensure that all eligible patients are tested, a new EHR query runs every evening to identify patients who are at least 18 years of age, who have no HCV diagnosis code or anti-HCV test result in their chart, and who have appointments the following day. An automatic reminder stating the patient's testing eligibility based on updated guidelines is then attached to the patient's chart.

The final adjustment was a response to testing fatigue and new, untrained staff members. The project manager now visits each clinic weekly to report the total numbers of tests performed and to identify and address problems before they become larger issues. As a result, an average of 211 more anti-HCV tests were performed monthly—a 63.9% increase—between the five months before (March–July 2015, n=330) and the five months after (August–December 2015, n=541) the adjustment.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Our testing model was integrated into a preexisting patient population; as such, our results may not represent those tested at community sites. The participating health centers also represent at-risk populations in a large urban county, and portions of this model may not be replicated at different care settings or in other areas of the country.

Second, the number of patients receiving HCV treatment at PHMC Care Clinic did not reflect the true number of patients who were receiving treatment for HCV. Many of the patients receiving treatment were not anti-HCV tested within the study time frame, data collection for patients receiving HCV care outside of PHMC Care Clinic was in the early stages, and the final processes were still being developed. As a result, updated linkage-to-care and treatment data were likely underreported.

CONCLUSION

Our model successfully integrated HCV testing into routine primary care and showed that a multipronged approach to HCV care can increase testing and improve linkage-to-care rates. The barriers to testing and care found in this project may also be encountered at other testing sites, and interventions used to overcome them may prove integral to success for HCV testing at other clinics nationwide.

Footnotes

The authors thank the medical staff and patients at Mary Howard Health Center, Public Health Management Corporation (PHMC) Care Clinic, PHMC Health Connection, Congreso Health Center, and Rising Sun Health Center for making this study possible; and Grace Lee from National Nursing Centers Consortium for extracting data from the electronic medical records. This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hepatitis C virus grant (CDC-RFA-PS12-1209PPHF12) and Frontlines of Communities in the United States, a program of Gilead Sciences, Inc. This article does not necessarily represent the views of CDC and/or Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Catelyn Coyle is a medical advisory member of Gilead Sciences, Inc., for which she received honoraria and travel compensation. All aspects of this project were considered part of a public health program and determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, editors. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington: National Academies Press; 2010. Institute of Medicine (US), Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward JW, Valdiserri RO, Koh HK. Hepatitis C virus prevention, care, and treatment: from policy to practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 1):S58–63. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, Ewelukwa O, Ditah C, Njei B, et al. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol. 2014;60:691–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SL, Morgan TR. The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:47–52. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:556–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965 [published erratum appears in MMWR Recomm Rep 2012;61(43):886] MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewett A, Garg A, Meyer K, Wagner LD, Krauskopf K, Brown KA, et al. Hepatitis C virus testing perspectives among primary care physicians in four large primary care settings. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16:256–63. doi: 10.1177/1524839914532291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward JW, Lok AS, Thomas DL, El-Serag HB, Kim WR. Report on a single-topic conference on “chronic viral hepatitis—strategies to improve effectiveness of screening and treatment.”. Hepatology. 2012;55:307–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.24797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens M, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007 [published erratum appears in Ann Intern Med 2012;156:840] Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:271–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong JB, McQuillan GM, McHutchison JG, Poynard T. Estimating future hepatitis C morbidity, mortality, and costs in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1562–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tohme RA, Xing J, Liao Y, Holmberg SD. Hepatitis C testing, infection, and linkage to care among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, 2009–2010. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:112–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strehlow AJ, Robertson MJ, Zerger S, Rongey C, Arangua L, Farrell E, et al. Hepatitis C among clients of health care for the homeless primary care clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:811–33. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyle C, Viner K, Hughes E, Kwakwa H, Zibbell JE, Vellozzi C, et al. Identification and linkage to care of HCV-infected persons in five health centers—Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2012–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):459–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle C, Kwakwa H. Routine dual HCV and HIV testing: seroprevalence and linkage to care in four community health centers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(Suppl 1):41–52. doi: 10.1177/00333549161310S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allscripts. Chicago: Allscripts; 2013. Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2011. SAS®: Version 9.3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, Suryaprasad A, Sanders KJ, Moore-Moravian L, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years—Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onofrey S, Church D, Kludt P, DeMaria A, Cranston K, Beckett GA, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among adolescents and young adults—Massachusetts, 2002–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(17):537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, Lo Re V., 3rd The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viner K, Kuncio D, Newbern EC, Johnson CC. The continuum of hepatitis C testing and care. Hepatology. 2015;61:783–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trooskin SB, Poceta J, Towey CM, Yolken A, Rose JS, Luqman NL, et al. Results from a geographically focused, community-based HCV screening, linkage-to-care and patient navigation program. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:950–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3209-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffin PO, Reynolds A. Ending hepatitis C in the United States: the role of screening. Hepat Med. 2014;6:79–87. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S40940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]