Abstract

Objective

To comply with the 2012 CDC recommendations for hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening, we implemented a new HCV screening program for patients born between 1945 and 1965 at a South Texas safety-net hospital.

Methods

Patients with no HCV diagnosis or prior HCV test received an automated order for HCV antibody (anti-HCV) tests combined with reflex HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase chain reaction. An inpatient counselor educated anti-HCV-positive patients. A bilingual patient navigator assisted newly diagnosed chronic HCV patients with linkage to primary and specialty care. We examined results for Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic patients in the first 10 months of project implementation in 2013–2014.

Results

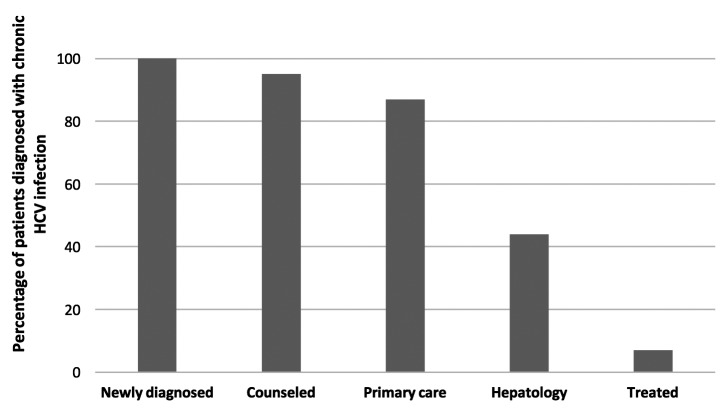

Of 2,327 patients screened for HCV, the 192 (8%) patients who tested anti-HCV positive were younger than those who tested negative (56 vs. 58 years, respectively, p<0.001) and more likely to be male (p<0.001). Of the 167 anti-HCV-positive patients tested for HCV RNA, 108 (65%) were HCV RNA positive (5% of cohort). Barriers to care for HCV RNA-positive patients included a lack of health insurance, current substance abuse, incarceration, and homelessness. Hispanic HCV RNA-positive patients were more likely than non-Hispanic HCV RNA-positive patients to be substance abusers or incarcerated. Of all HCV RNA-positive patients, 103 patients (95%) received counseling, 94 patients (87%) were linked to primary care, 47 patients (44%) were linked to specialty care, and eight patients (7%) started treatment.

Conclusion

The prevalence of anti-HCV-positive and chronically HCV-infected patients was higher than many Hispanic or non-Hispanic white cohorts. Most Hispanic patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV had barriers to care for HCV infection that must be overcome if HCV screening is to reduce morbidity and mortality in this population.

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a significant source of morbidity and mortality in the United States, where most of the estimated 2.7 million people with chronic HCV are unaware of their infection.1–3 HCV is a major contributing factor to the rise of hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is now the leading indication for liver transplantation nationally.4–7 In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its HCV prevention recommendations to include one-time HCV screening of all people born between 1945 and 1965.3 This birth cohort, known as baby boomers, accounts for an estimated 75% of all HCV infections and 73% of HCV-associated mortality. Additionally, this group has the greatest risk for HCC and other HCV-related complications.3,8

Marked racial/ethnic disparities persist in the prevalence and impact of chronic HCV infection.1,9,10 HCV prevalence in those who self-identify as non-Hispanic black is higher than in other racial/ethnic groups.1,11 Among those who self-identify as Hispanic, population-based surveys reveal that HCV antibody (anti-HCV) prevalence differs markedly by country of origin or ancestry, with a higher prevalence in people of Puerto Rican vs. Mexican descent.12 Mortality rates from HCV in Hispanic and non-Hispanic black people are twice those observed for non-Hispanic white people.13 Among people with HCC, Hispanic people have substantially poorer survival rates than non-Hispanic white people.14 HCV infection is also associated with lower income and education levels,1 placing members of poor minority communities at high risk for morbidity and mortality from HCV.

In South Texas, two-thirds of the population self-identifies as Hispanic, with 94% of Mexican origin. Hispanic people in South Texas have the highest prevalence of HCV infection in Texas, and the risk of HCC is three to four times greater than that of non-Hispanic white people in this region.15–17 Chronic HCV infection is present in 50%–60% of people with HCC and is a major target in preventing not only HCC, but also cirrhosis and other sequelae of the disease.18

To address the important health threat of undiagnosed HCV infection in South Texas, we began screening all baby boomers admitted to the largest public hospital in South Texas in December 2012. This inpatient testing program provided screening and linkage-to-care services for people who may have had limited access to ambulatory care. Our program provided anti-HCV testing; reflex HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for confirmation of chronic HCV infection in patients with detectable anti-HCV; counseling; and linkage-to-care and treatment services. We describe successes and challenges from the first 10 months of our program and examine ethnic disparities in the screened population by comparing program results between Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants.

METHODS

Study setting and project development phase

We pilot tested the HCV baby boomer screening program in November 2012 and officially launched the program on December 1, 2012, at University Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, a 498-bed, academic-affiliated hospital in a health-care system serving South Texas' indigent population.

Prior to initiating the screening program, we conducted provider and staff member education—including informational lectures to nursing supervisors, departmental chairs of the affiliated medical school, resident physicians, and leadership—and departmental grand rounds. We held meetings with key hospital stakeholders, including representatives from hospital administration, laboratory, and information technology.

We developed an automatic screen in the electronic medical record (EMR)19 to identify inpatients eligible for screening by searching for certain birth years (1945–1965) and by examining up to seven years' of inpatient and outpatient encounters for exclusion criteria, including diagnosis of HCV infection using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7x, V02.62, or any previously completed test for HCV. Our algorithm excluded patients admitted to the psychiatry service who may have been incompetent and those patients with poor prognoses, such as metastatic cancer (codes available upon request).20

An HCV screening laboratory order was automatically added to the admission order set for identified eligible patients. The order combined an anti-HCV test with a reflex HCV RNA test to confirm chronic HCV infection, as recommended by CDC.21 The anti-HCV test was performed on either serum or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma using the Advia® Centaur” HCV Assay (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Tarrytown, New York). This assay had excellent sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (97.5%).22 Patients reactive for anti-HCV were tested for plasma HCV RNA by quantitative real-time PCR using the COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HCV Test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, California). For most patients, specimens were collected in plasma preparation tubes (BD Vacutainer® PPT” tubes; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey), allowing both anti-HCV screening and HCV RNA PCR confirmatory testing to be performed on the same specimen and avoiding an additional blood draw. If specimens were not collected in plasma preparation tubes and the patient had a positive anti-HCV test, a study team member reached out to the patient and provider to ensure that an HCV RNA PCR confirmatory test was ordered.

Floor nursing supervisors and their nurses were trained to obtain consent from patients for HCV screening during their intake session with admitted patients. If a patient opted out of testing, floor nurses had to discontinue the HCV screening laboratory order set from the patient's admission orders. Upon review of results of the first months of screening, we adapted this procedure to improve testing update, as described later.

To counsel and educate anti-HCV-positive patients, we developed an interactive, low-literacy, educational program in Spanish and English for a tablet device (“HCV app”) that addressed HCV epidemiology, transmission prevention, and management/treatment strategies. The patient had to correctly answer content questions to continue, and the program concluded with screening for alcohol consumption (using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT-C]), drug use, and men who have sex with men so that patient-appropriate counseling messages could be delivered.23

Project implementation

A patient education campaign notified admitted patients about the screening program and included CDC-approved signage with posters placed throughout the hospital and informational flyers added to every admission package.

An EMR-generated report classified all baby boomers admitted in the previous 24 hours as (1) eligible without anti-HCV test ordered, (2) eligible with anti-HCV test pending, (3) ineligible because of prior HCV test or diagnosis, or (4) ineligible because of comorbidity (e.g., metastatic cancer or psychiatric condition). The study team monitored daily admission lists for eligible patients who did not have an HCV screening test as part of their admission order set. HCV screening tests were not automatically added to the admission order set approximately 25% of the time if providers used an uncommon admission order set lacking the automated HCV screen or did not use an order set to admit the patient. The study team manually ordered HCV screening tests for a majority of these patients, although this process infrequently led to a delay in the order being processed, and some patients with short hospital stays were discharged prior to screening. A bilingual counselor provided HCV screening test results to inpatients, reviewed the 15-minute HCV app with anti-HCV-positive patients, and answered questions. Again, if the reflex HCV RNA test was not performed, the counselor arranged for follow-up HCV RNA testing.

One week after hospital discharge, a bilingual community health worker (“promotora”) telephoned patients diagnosed with chronic HCV infection or who still needed confirmatory HCV RNA testing. Traditionally, a promotora is a trusted member of the target community dedicated to promoting health for his or her community.24,25 For this project, the promotora had specific training in motivational interviewing and community health work but no formal medical training. The promotora worked in the outpatient setting to address patients' barriers to HCV care, including lack of health insurance, no primary care provider, needing referral to HCV specialty care, problems with appointment scheduling, and treatment for alcohol or drug abuse. After obtaining signed consent, the promotora sent test results to the patient's outpatient clinician and recommended follow-up care (e.g., hepatitis A and B immunization).

Study data

An EMR-generated summary report included demographic, health insurance, clinical, and health-care variables for all admitted baby boomers. For patients identified with chronic HCV infection, the promotora obtained data about follow-up HCV care, health insurance status, homelessness, and drug and alcohol use/abuse through May 31, 2015, from direct patient communication and by reviewing outpatient medical records within the same health-care system. Harmful or hazardous alcohol use was identified from ICD-9-CM codes associated with the hospital admission when the HCV screen was applied, the presence of alcohol abuse on the problem list of provider admission or progress notes, or a score of 8+ on the AUDIT-C test (range: 0–12, ≥8 associated with a high rate of alcohol dependence) administered via the HCV app.23 Active substance use was identified by ICD-9-CM codes for the hospital admission, clinician notes describing active substance use, or patient acknowledgment of substance abuse within the past year via the HCV app.

Data gathered for this project, including the aforementioned health variables and those gathered during counseling (e.g., risk factor data and alcohol use), were indicated in the routine clinical care of individuals screened and diagnosed with HCV. No additional data were obtained outside of those required for patient management. For the purposes of this project, we defined “linkage to care” as attending an outpatient visit with a medical provider—either a primary care provider or subspecialty provider as noted—in which the provider's visit note specifically addressed HCV.

Statistical analysis

We compared characteristics of anti-HCV-positive patients with those who had a negative test, overall and by ethnicity, using binomial, c2, Fisher's exact, Wilcoxon signed-rank, or Kruskall-Wallis tests, as appropriate. Among anti-HCV-positive patients, we compared characteristics of HCV RNA-positive with HCV RNA-negative patients overall and by ethnicity. We used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using proc logistic in SAS® version 9.4.26 We considered associations to be significant at p≤0.05 using a two-sided test.

Program evaluation

A preliminary program evaluation conducted one month after program implementation included an assessment of the number of eligible people who were screened and a manual EMR-based audit of 100 patients excluded by the automated eligibility screen to evaluate whether or not these patients met exclusion criteria. Subsequently, the program evaluation team, including the inpatient counselor, the promotora, an internist, and an infectious diseases physician, reviewed screening program results monthly. The inpatient counselor solicited continuous feedback on the HCV app to determine patient response to this counseling modality and suggestions for improvement. Further details regarding implementation costs are described elsewhere.27

RESULTS

Antibody screening results

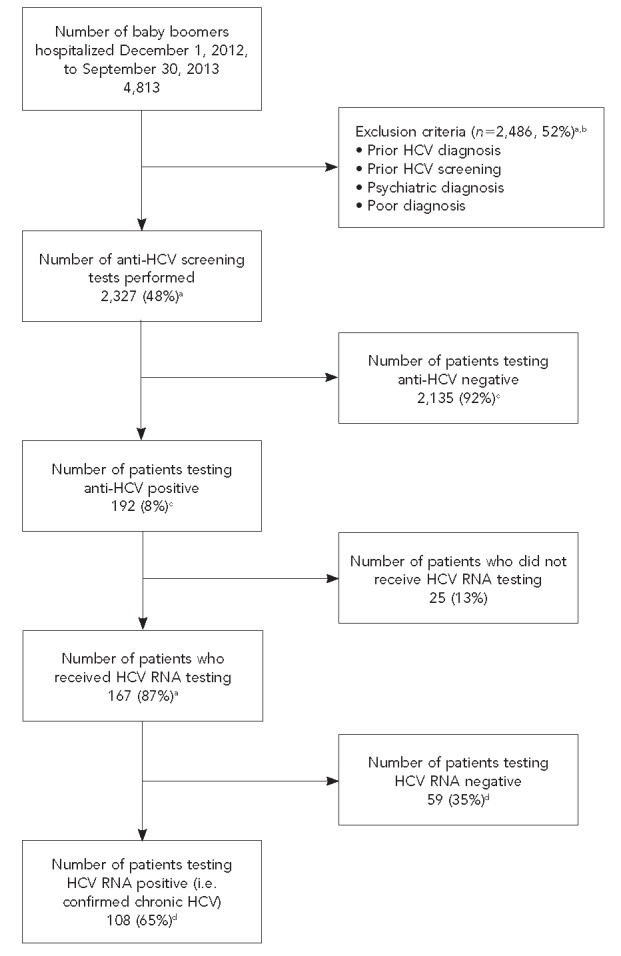

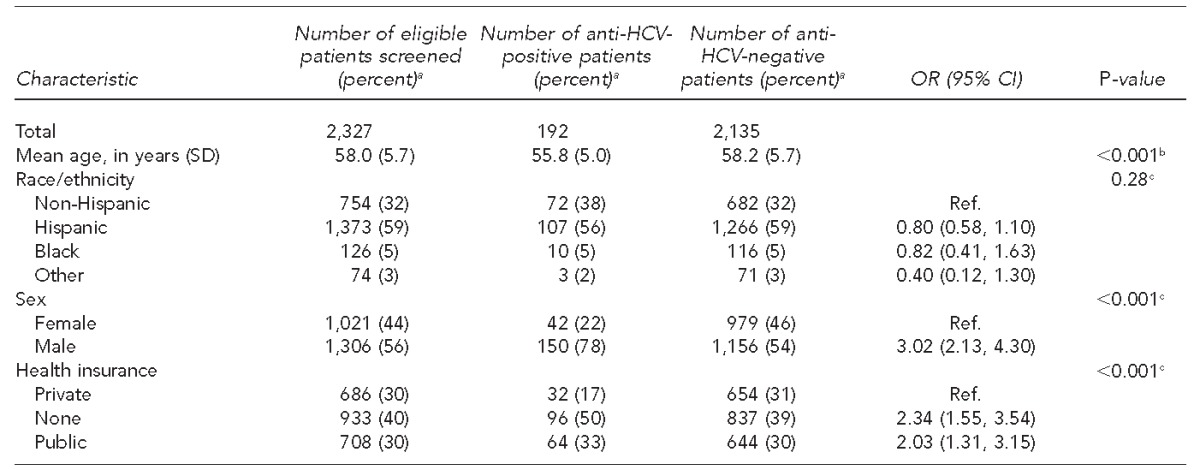

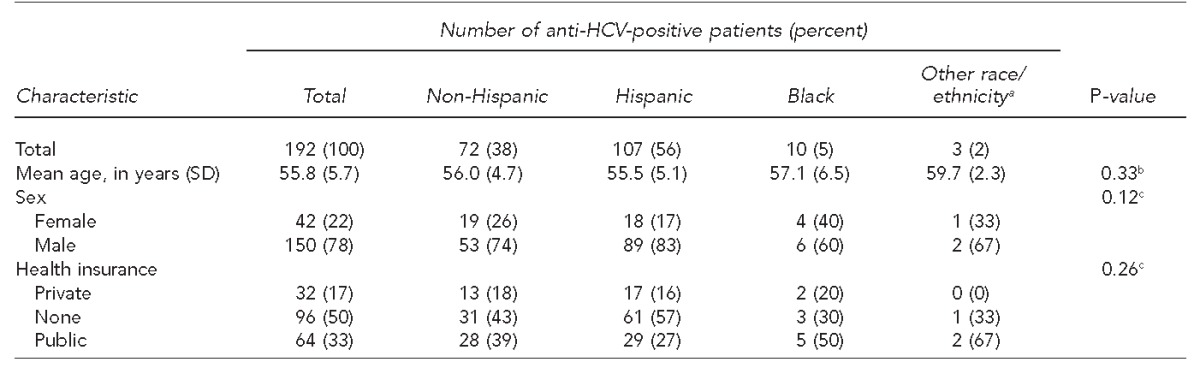

In the first 10 months of the inpatient HCV screening program, 4,813 unique patients born between 1945 and 1965 were admitted to University Hospital. Of these patients, 2,327 (48%) met eligibility criteria for HCV screening and received testing for HCV infection (Figure 1). Of the 2,327 patients screened, 192 (8%) were anti-HCV positive, of whom 107 (56%) were Hispanic (Table 1). Compared with eligible patients screened, anti-HCV-positive patients were more likely to be male (OR=3.02, 95% CI 2.13, 4.30) and slightly younger (mean age: 56 vs. 58 years, respectively, p<0.001). The prevalence of anti-HCV (8% for Hispanic patients and 10% for non-Hispanic patients) did not differ significantly by ethnicity (p=0.28). We also found no significant ethnic differences for anti-HCV-positive patients in mean age, sex, or health insurance type (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of all patients with hepatitis C virus born between 1945 and 1965 who had screening tests performed, University Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, 2012–2013

aPercentage of total baby boomers admitted

bOther exclusions included psychiatric hospitalization, metastatic carcinoma, hospice care, or <6 months to live.

cPercentage of those screened

dPercentage of those HCV RNA tested

HCV = hepatitis C virus

anti-HCV = HCV antibody

RNA = ribonucleic acid

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients born between 1945 and 1965 who were screened for anti-HCV, University Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, 2012–2013

aNot all percentages total to 100 because of rounding.

bWilcoxon signed-rank test

cc2 test

anti-HCV = hepatitis C virus antibody

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

SD = standard deviation

Ref. = referent group

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients born between 1945 and 1965 with detectable anti-HCV (n=192), by race/ethnicity, University Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, 2012–2013

aOther race/ethnicity includes Asian, Pacific Islander, and mixed race.

bKruskal-Wallis test

cFisher's exact test

anti-HCV = hepatitis C virus antibody

SD = standard deviation

Diagnosis of chronic HCV infection in entire cohort and by ethnicity

Of the 192 anti-HCV-positive patients, 25 (13%) did not receive follow-up HCV RNA PCR testing (Figure 1). Of the 167 patients tested, 108 (65%) had detectable HCV RNA PCR indicating chronic HCV infection. For the entire screened cohort, the prevalence of detected chronic HCV infection was 5%.

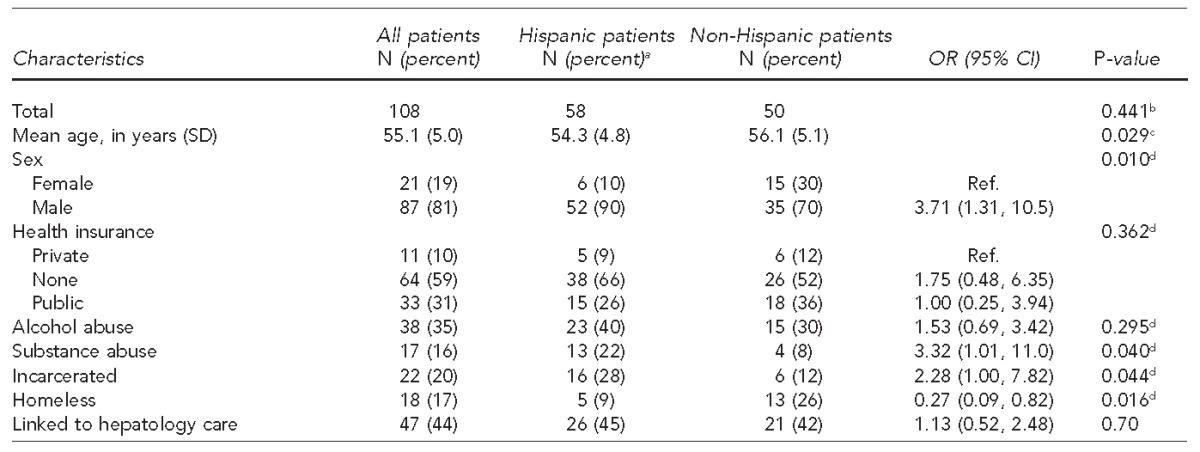

We examined patient characteristics and barriers to care by ethnicity for the 108 patients diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, defined as being anti-HCV-positive and HCV RNA PCR positive (Table 3). Barriers to care for this newly diagnosed population included lack of health insurance (59%), incarceration (20%), homelessness (17%), and substance abuse (16%). Because only seven African American patients were newly diagnosed with HCV, they were combined with the non-Hispanic ethnicity category for analysis, and we did not conduct an analysis by race. Compared with non-Hispanic patients with chronic HCV, Hispanic patients were younger (mean age: 54 vs. 56 years, respectively, p=0.029) and more likely to be male (OR=3.71, 95% CI 1.31, 10.50) and substance users (OR=3.32, 95% CI 1.01, 11.00), but less likely to be homeless (OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.09, 0.82).

Table 3.

Characteristics, barriers to care, and linkage-to-care outcome of patients born between 1945 and 1965 newly diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C virus infection, by ethnicity, University Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, 2012–2013

aNot all percentages total to 100 because of rounding.

bBinomial test

cWilcoxon signed-rank test

dc2 test

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

SD = standard deviation

Ref. = referent group

Engagement in care and treatment

The inpatient counselor and outpatient promotora counseled 103 of 108 (95%) patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV infection and attempted to link them to care and treatment (Figure 2). After at least 20 months of post-diagnosis follow-up, 94 of the 108 (87%) patients had been linked to care with a primary care physician, and 47 of the 108 (44%) patients had received specialty care for HCV infection. Only eight of the 108 (7%) patients received disease-specific treatment for HCV infection, but many patients were still awaiting treatment with pegylated interferon alpha (IFN-α)-free regimens. Of those newly diagnosed with HCV infection, no demographic characteristics were significantly associated with successful linkage to hepatology care.

Figure 2.

Continuum of care for patients born between 1945 and 1965 newly diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C virus infection, University Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, 2012–2013

HCV = hepatitis C virus

Results of program evaluations and program adaptation

The start-up program evaluation occurred one month into the screening program. Barriers to successful project implementation fell into four broad categories: information technology, providers, health-care system, and characteristics of the patient population. First, as the project relied heavily on automated EMR-based algorithms to determine screening eligibility and add the HCV test to admission order sets, we assessed information technology barriers. The manual audit of 100 patients excluded by the automated EMR screen showed that these patients had a legitimate exclusion, so no changes were made. Manual order entry was still required for the 25% of patients for whom the order was not automatically added to the admission order set by the coding algorithm—an information technology hurdle that multiple iterations of the screening program could not overcome.

Second, an assessment of provider (i.e., nurses and physicians) barriers revealed that more than 60% of patients who met HCV screening eligibility did not have the test performed, because nurses were not engaging in the informed-consent process with patients for testing. After discussions with nursing supervisors and hospital staff members, we deemed the informed-consent process too onerous for nurses to engage in during intake evaluations, which are already time consuming. We changed the protocol to opt-out consent, with patients learning about the program from posters placed around the hospital and flyers included in admission packets. Subsequently, fewer than 5% of patients opted out of testing. Subsequent monthly program evaluations found that 75% of eligible patients had the HCV screening order set added to their admission orders. Physician providers also reported concerns that newly diagnosed patients would not be followed up with and linked to care, so we continued provider education in group settings (i.e., resident report, staff rounds) and one on one to address provider concerns and describe our linkage-to-care efforts.

Third, barriers at the health-care system level included limited access to the hepatology clinic, long waits for new appointments, and difficulty navigating the referral process. We addressed these barriers through close collaboration with the gastroenterology faculty to expedite referrals of newly diagnosed patients and additional training of the promotora in case management to assist patients in accessing primary care services. Both the counselor and promotora requested that the HCV app offer a more in-depth explanation of the importance of engagement in primary care, and this adaptation was made.

Fourth, the majority of our patient population lacked health insurance, and many experienced incarceration, homelessness, or problems with alcohol or substance use. We gave the promotora additional training in how to assist patients in applying for insurance, increased communication between the promotora and the county jail and local homeless shelters, and trained the counselor and promotora in motivational interviewing to address substance and alcohol use.

DISCUSSION

We found that the 8% prevalence of HCV infection, as measured by the presence of anti-HCV, was higher than that reported in other cohorts1,12 but similar or lower than two studies conducted in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.28,29 The 35% prevalence of detectable anti-HCV in undetectable HCV RNA PCR, usually indicative of cleared infection, was also high in this cohort, which was consistent with more recent population-based surveys and baby boomer screening programs.1,29

The high prevalence of detectable anti-HCV in this majority Mexican American population is noteworthy and concerning.30 The 8% anti-HCV-positive prevalence for Hispanic people in this cohort was nearly four times the prevalence seen in Hispanic people of Mexican descent in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2007–2010 (2%), or the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (2%).1,12 These data are more in line with anti-HCV-positive prevalence in Hispanic people of Puerto Rican descent. Further investigation is needed to determine why anti-HCV-positive prevalence was elevated in this cohort.

We observed that 65% of anti-HCV-positive patients progressed to chronic HCV infection, as demonstrated by a detectable HCV RNA PCR, which was consistent with findings from other population-based surveys.1,12 Previous reports for populations screened by risk factors have stated that as many as 85% of people initially infected with HCV progress to chronic infection.31,32 Factors contributing to this discrepancy may include the type of screening (i.e., risk factor vs. population-based), higher rates of spontaneous HCV clearance in Hispanic and younger people,33,34 and genetic factors.35 False-positive anti-HCV results were unlikely with the highly specific assay used.22 These results highlight the need for confirmatory HCV RNA PCR testing when screening baby boomers for HCV infection.

Multiple barriers to care existed for those patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, including lack of health insurance, alcohol and substance abuse, and incarceration. These barriers were more common in newly diagnosed patients who self-identified as Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic. Lack of health insurance was the most significant barrier to care; 57% of chronically infected Hispanic patients and 43% of non-Hispanic white patients reported not having health insurance. Unfortunately, the South Texas region has the highest prevalence of uninsured people in the nation.30 Barriers of alcohol abuse, active substance abuse, and incarceration were more common in Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic patients, indicating likely reasons for disparities in access to care for this population.36 Although our program was able to mitigate many linkage-to-care barriers through intensive support from the promotora, only 38% of our patients accessed subspecialty hepatology care for their chronic HCV infection, and only 5% received HCV-specific treatment. During the course of the implementation project, HCV treatment modalities evolved substantially. At project initiation, IFN-α and ribavirin-based regimens were most commonly used; by the end of data collection, IFN-α-free regimens were available in the safety-net health-care system, and patients awaiting these treatments were beginning to receive them.

Our review of the first 10 months of this HCV baby boomer screening project revealed several key approaches for implementation of similar programs to conduct HCV screening. First, it was essential to work closely with the hospital's information technology department to capture patients for automated screening. Second, considering the high percentage (35%) of patients with detectable anti-HCV but undetectable HCV RNA PCR, automatic reflex testing of those with a positive anti-HCV test by HCV RNA PCR was critical to identifying patients with chronic HCV infection. Third, additional training for the promotora in case management and motivational interviewing offered a valuable approach to addressing barriers to care engagement. Finally, although few patients (5%) initiated curative treatment for HCV in the first year after diagnosis, many who were ineligible for interferon-based regimens were candidates for newer, all-oral regimens. Ongoing efforts are required to continue to engage these patients in care now so they can access these better-tolerated regimens as they become available. Given the high burden of HCV infection among the uninsured, it will be necessary to develop strategies to provide access to newer regimens to this vulnerable population.

CONCLUSION

We reported on the implementation of a successful HCV screening program that, in only 10 months, tested more than 2,300 baby boomers admitted to a large, safety-net hospital in South Texas and was accepted by 95% of the target population. We found a higher prevalence of detectable anti-HCV (8%) and chronic HCV infection (5%) than previously reported in other cohorts of Hispanic people of Mexican descent, emphasizing the high impact that HCV screening programs can have in this region. Such HCV screening programs will only have an effect if the significant challenges to care we encountered (i.e., lack of insurance, lack of access to treatment, homelessness, alcohol abuse, and incarceration) can be addressed. If access to life-saving care and treatment for chronic HCV infection can be assured, our automated screening program integrated with standard hospital care should be considered as a model for other health-care systems. Successful implementation of HCV screening is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality from chronic HCV infection in high-prevalence, majority-Hispanic populations.

Footnotes

The authors thank Mary Elizabeth Perez, the inpatient counselor, and Ludivina Hernandez, the outpatient promotora, who worked to counsel patients and engage them in care throughout the project; Rosamaria Ortiz for order entry, Shruthi Vale for project coordination, and all the nurses, counselors, laboratory technicians, and staff members from University Health System who were involved in the project; and all the patients for their acceptance of this initiative and suggestions for improvement.

The University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio Institutional Review Board reviewed this implementation project and deemed it to be exempt because it was a program implementation and not considered human subjects research. The project was funded through a grant for hepatitis C virus screening from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC PS12-1209PPHF12). CDC had no role in the analysis or interpretation of results or the generation of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornschlegel K, Holtzman D, Klevens M, Ward JW. Vital signs: evaluation of hepatitis C virus infection testing and reporting—eight U.S. sites, 2005–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(18):357–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanwal F, Hoang T, Kramer JR, Asch SM, Goetz MB, Zeringue A, et al. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1182–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part III: liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1134–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simard EP, Ward EM, Siegel R, Jemal A. Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:118–28. doi: 10.3322/caac.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guy J, Yee HF., Jr Health disparities in liver disease: time to take notice and take action. Hepatology. 2009;50:309–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.22942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawls RA, Vega KJ. Viral hepatitis in minority America. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:144–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G, Holmberg SD, Kamili S, Xu F. Racial disparities in the proportion of current, unresolved hepatitis C virus infections in the United States, 2003–2010. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1950–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuniholm MH, Jung M, Everhart JE, Cotler S, Heiss G, McQuillan G, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in US Hispanic/Latino adults: results from the NHANES 2007–2010 and HCHS/SOL studies. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1585–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise M, Bialek S, Finelli L, Bell BP, Sorvillo F. Changing trends in hepatitis C-related mortality in the United States, 1995–2004. Hepatology. 2008;47:1128–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.22165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davila JA, El-Serag HB. Racial differences in survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yalamanchili K, Saadeh S, Lepe R, Davis GL. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Texas: implications for future health care. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005;18:3–6. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramirez AG, Munoz E, Holden AE, Adeigbe RT, Suarez L. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in Texas Latinos, 1995–2010: an update. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez AG, Weiss NS, Holden AE, Suarez L, Cooper SP, Munoz E, et al. Incidence and risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Texas Latinos: implications for prevention research. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allscripts. Chicago: Allscripts; 2013. Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics (US) International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) [cited 2012 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm.

- 21.Getchell JP, Wroblewski KE, DeMaria A, Jr, Bean CL, Parker MM, Pandori M, et al. Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(18):362–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor P, Pickard G, Gammie A, Atkins M. Comparison of the ADVIA Centaur and Abbott AxSYM immunoassay systems for a routine diagnostic virology laboratory. J Clin Virol. 2004;30(Suppl 1):S11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albarran CR, Heilemann MV, Koniak-Griffin D. Promotoras as facilitators of change: Latinas' perspectives after participating in a lifestyle behaviour intervention program. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2303–13. doi: 10.1111/jan.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parra-Medina D, Morales-Campos DY, Mojica C, Ramirez AG. Promotora outreach, education and navigation support for HPV vaccination to Hispanic women with unvaccinated daughters. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30:353–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0680-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2015. SAS®: Version 9.4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner BJ, Taylor BS, Hanson JT, Perez ME, Hernandez L, Villarreal R, et al. Implementing hospital-based baby boomer hepatitis C virus screening and linkage to care: strategies, results, and costs. J Hosp Med. 2015;8:510–6. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady KA, Weiner M, Turner BJ. Undiagnosed hepatitis C on the general medicine and trauma services of two urban hospitals. J Infect. 2009;59:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coyle C, Viner K, Hughes E, Kwakwa H, Zibbell JE, Vellozzi C, et al. Identification and linkage to care of HCV-infected persons in five health centers—Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2012–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):459–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Census Bureau (US) Small area health insurance estimates 2012 [cited 2014 Nov 13] Available from: http://www.census.gov/did/www/sahie.

- 31.Shakil AO, Conry-Cantilena C, Alter HJ, Hayashi P, Kleiner DE, Tedeschi V, et al. Volunteer blood donors with antibody to hepatitis C virus: clinical, biochemical, virologic, and histologic features. The Hepatitis C Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:330–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-5-199509010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heintges T, Wands JR. Hepatitis C virus: epidemiology and transmission. Hepatology. 1997;26:521–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolfe KJ, Curran MD, Alexander GJ, Woodall T, Andrews N, Harris HE. Spontaneous loss of hepatitis C virus RNA from serum is associated with genotype 1 and younger age at exposure. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1338–44. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busch MP, Glynn SA, Stramer SL, Orland J, Murphy EL, Wright DJ, et al. Correlates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA negativity among HCV-seropositive blood donors. Transfusion. 2006;46:469–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grebely J, Dore GJ, Kim AY, Lloyd A, Shoukry NH, Prins M, et al. Genetics of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus infection: a complex topic with much to learn. Hepatology. 2014;60:2127–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.27163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Cejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2005. Vital Health Stat. 2006;10(232) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]