Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a toxic gas that has been recognized as an important mediator of many physiological processes, such as neurodegeneration, regulation of inflammation, blood pressure, and metabolism. In the human colon, H2S is produced by both endogenous enzymes and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB). H2S is involved in the physiological and pathophysiological conditions of the colon, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer (CRC), which makes the pharmacological modulation of H2S production and metabolism a potential chemical target for the treatment of colonic diseases. However, the exact mechanisms and pathways by which H2S-mediates normal physiological function and disease in the colon are not fully understood. Besides, the production and release of H2S are modulated by both endogenous and exogenous factors. This review will discuss the production and storage of H2S, its biological roles and the emerging importance in physiology and pathology of IBD and CRC.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide, sulfate-reducing bacteria, pathophysiological roles, colonic diseases, chemical target

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a pungent gas that smells like rotten eggs, and has been identified as the third gaseous transmitter, following nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO; Gallego et al., 2008). Since the discovery of its synthesis in mammalian and human tissues, it has attracted much interest as an endogenous mediator in recent years (Whiteman et al., 2011). Over the last decade, H2S has been recognized to have various biological effects in human health and diseases, such as in the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, and the immune system (Kimura, 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Recently, studies involving the physiological and pathophysiological effects of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) have attracted much attention. Multiple studies also imply the important role of H2S in colonic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; Wallace et al., 2009; Hirata et al., 2011) and colorectal cancer (CRC) (Cai et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Kimura, 2011). In the present review, we will discuss the endogenous and exogenous production of H2S, and its biological and pathological roles in IBD and CRC.

Endogenous production and biological roles of H2S

The concentration of H2S ranges from 0.2 to 1 mmol/L in the colon of mice and may reach 3.4 mmol/L in human stools (Rose et al., 2005). Under normal conditions, approximately 70% of H2S is produced from cysteine and the other 30% from homocysteine (Chiku et al., 2009). There are three principal enzymes involved in the endogenous production of H2S: cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). They are expressed in many organs, including the liver, kidney, ileum, and brain (Kimura, 2011). CBS and CSE have been investigated widely, and both use vitamin B6 as a cofactor to catalyze the production of H2S (Chiku et al., 2009). The catalytic effect of CBS changes with the extent of allosteric activation of S-adenosylmethionine (Singh et al., 2009), and the activity of CSE is enhanced by sodium nitroprusside (SNP; Chiku et al., 2009). A study also shows that CSE is regulated by calcium calmodulin, although the requirement for Ca2+ concentrations is quite high (1 mM; Yang et al., 2008). The role of 3-MST along with cysteine aminotransferase (CAT), which can efficiently produces H2S from cysteine and a-ketoglutarate (Kimura, 2011), in regulating endogenous H2S levels has recently been examined in specific types of cells and tissues (Shibuya et al., 2009b; Wang, 2012).

H2S may function as a signal molecule immediately after released from the enzyme; it can also be stored as bound sulfane sulfur, which may in turn release H2S (Whiteman et al., 2011). At physiological pH, nearly two-thirds of H2S exists as the hydrosulfide anion (HS−), which is a powerful nucleophile (Bouillaud and Blachier, 2011).

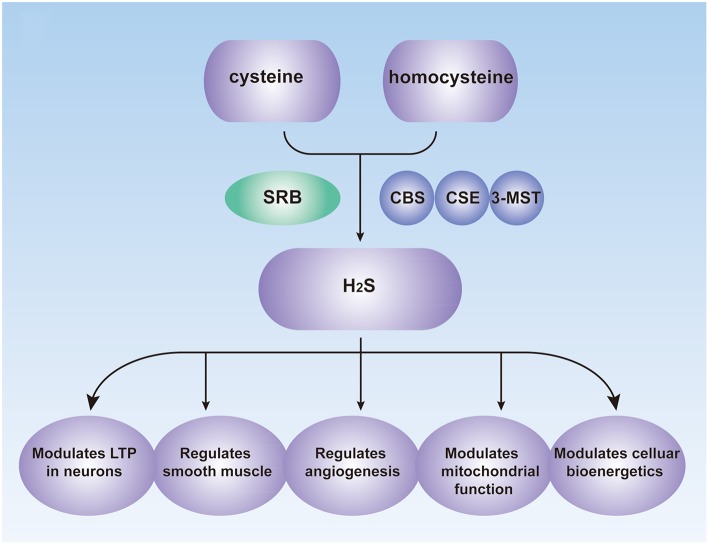

Endogenous H2S performs vital roles in many physiological processes, including vasorelaxation, angiogenesis, cellular energy production, neuromodulation, cytoprotection, and pathological processes (Figure 1; Kimura et al., 2010; Coletta et al., 2012), and it is now considered as a signaling modulator or a messenger molecule (Farrugia and Szurszewski, 2014). H2S was initially considered as a neuromodulator that aids the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) by enhancing NMDA-induced currents in neurons (Abe and Kimura, 1996; Nagai et al., 2004). H2S may also mediate the reciprocal interactions between glial calcium waves and neuronal activity, which has not been fully investigated (Kimura, 2011). Prior studies also showed that transient receptor potential (TRP) channels might be involved in the effects of H2S (Patacchini et al., 2005; Gratzke et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Biological Roles of H2S in the human. CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; CSE, cystathionine γ-lyase; 3-MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; SRB, sulfate-reducing bacteria; LTP, long-term potentiation.

H2S also functions as signal molecule in smooth muscle relaxation. Although NO performs most of the vessel-relaxing work in large vessels, H2S may be responsible for similar actions in smaller blood vessels (Wang, 2009). The mechanisms of H2S-mediated vasodilation may involve the activation of KATP channels or other channels, the inhibition of phosphodiesterases and synergy with NO (Wang, 2012).

The important pro-angiogenic role of H2S has also been recognized (Coletta et al., 2012). Angiogenesis is a complex biological process involved in endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and formation of capillary structures (Roudsari and West, 2015). Pupo et al. showed that endogenous H2S is involved in the angiogenic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key growth factor and tumor-derived angiogenic hormone (Pupo et al., 2011). Other studies showed that H2S exerts its effects via multiple mechanisms including activation of VEGFR2, stimulation of potassium channels and increase of cellular glutathione (GSH) levels (Cai et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Kimura et al., 2010; Tao et al., 2013).

In addition to serving as a signal molecule, H2S also participates in concentration-dependent modulation of mitochondrial function and cellular bioenergetics. In various cell types (including intestinal epithelial cells and hepatocytes), low concentrations of H2S act as mitochondrial electron donors, which results in the stimulation of bioenergy (Szabo et al., 2014). They increase the levels of glutathione and redistribute it to the mitochondria. In addition, they can promote the catalytic activity of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH (Mustafa et al., 2009). Endogenous H2S may also serve as a bioenergetic stimulator (Modis et al., 2013a,c). H2S produced by 3-MST along with CAT can scavenge reactive oxygen species in mitochondria and protect cells from oxidative stress (Kimura et al., 2010). Modis et al. demonstrated that H2S donors could stimulate mitochondrial electron transport and ATP generation in various cell lines in vitro (Modis et al., 2013b).

However, when the concentrations of this molecule are relatively high, the stimulatory effect of H2S is superseded by an inhibitory effect (Szabo et al., 2014), and high concentration of H2S may become a broad-spectrum poison to the nervous system, respiratory system and cardiovascular system (Wang, 2012). The concentration of H2S produced naturally in the human body is much lower than the toxic levels, which may be necessary for cell survival (Kimura, 2011).

The complexities of H2S biology may be related to its pharmacology. It is a diffusible gas and has a bell-shaped or biphasic dose-response curve, whereby lower concentrations of H2S show quite different (often, opposing) effects compared with higher concentrations (Szabo et al., 2013). Lower levels of H2S exert multiple physiological, cytoprotective, antioxidant and, anti-inflammatory functions. At higher local levels, however, H2S can become prooxidant, cytostatic, and cytotoxic (Baskar and Bian, 2011). However, these studies are limited by the lack of enzyme-specific inhibitors to target H2S biosynthesis, which may be related to the above-mentioned controversial observations (Whiteman et al., 2011).

Biological roles of H2S in the GI tract

Emerging evidence indicate that endogenous H2S can be produced and released by colonic tissue (Linden et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2010). In the GI tract H2S is mainly produced by CBS and CSE. CSE seems to be the main H2S-generating enzyme in the stomach, while CBS is the major enzyme in the colon (Wallace et al., 2009). The functions of H2S in the GI tract have also received much attention in recent years. It can relax ileal smooth muscle, increase colonic secretion (Gallego et al., 2008; Matsunami et al., 2009), and protect the intestines from ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats (Liu et al., 2009). However, high levels of H2S may also cause diseases, such as IBD and CRC.

Roles of exogenous H2S donors

There are multiple reports related to exogenous H2S donors in tumor cells that either promote or inhibit cell proliferation at different concentrations (Baskar and Bian, 2011; Wu et al., 2012). Previous studies have attempted to use various molecules to produce H2S (Kashfi and Olson, 2013), such as NSAIDs (Chattopadhyay et al., 2013; Kashfi, 2014), GYY4137 [morpholin-4-ium 4 methoxyphenyl (morpholino)] (Ning et al., 2014), S-propargyl-cysteine (Ma et al., 2011), Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) (Cai et al., 2010), Na2S (Hirata et al., 2011). The pros and cons of these molecules are summarized in a review article by Hellmich et al. (2015). Among them NaHS is most widely used to study the physiological functions of H2S. NaHS is a fast-release H2S donor, which immediately dissociates and forms the hydrosulfide anion (HS−) in the liquid culture, and reacts with H+ to form H2S.

Many studies have reported duplex effects of H2S on cell proliferation/cell death in various transformed and non-transformed cell lines in vitro (Leschelle et al., 2005; Cai et al., 2010; Murata et al., 2014). Baskar et al. have summarized most of these reports in a review article (Baskar and Bian, 2011). Note that the effects of H2S donors are bi-phasic, just like endogenously produced H2S. Cai et al. reported a concentration-dependent stimulation of cell growth by NaHS at doses between 10 and 50 μM, a plateauing of the effect at 200 μM, and an inhibition of proliferation at 1000 μM in HCT116 and SW480 cells (Cai et al., 2010). Hellmich et al. also demonstrated that the nature of the cellular response (stimulation or inhibition of growth) is determined by the rate of H2S production (fast- vs. slow-release H2S donors) as well as by the concentration of donor relative to the basal level of endogenous enzyme-dependent H2S production (Hellmich et al., 2015). It should be considered that H2S donors with different release rates might induce quantitative, as well as qualitative, variance in cellular responses (Whiteman et al., 2010; Baskar and Bian, 2011).

Thus, the bell-shaped properties of H2S provide a useful framework to reconcile some of the controversies regarding H2S functions. However, the complexities of the temporal relationship between H2S donation and its effects remain to be further explored.

Bacteria associated with hydrogen sulfide metabolism

H2S was one of the earliest products of bacterial decomposition to be recognized (Shatalin et al., 2011). Sulfur reduction and oxidation are handled by two different groups of bacteria. The former comprise the sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and sulfur-reducing bacteria, while the latter includes sulfur-oxidizing bacteria and sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (Wang, 2012). They both contribute to a balanced H2S level in a given environment. Among them, SRB belong to the most ancient forms of bacteria and utilize a wide range of substrates, including hydrogen, short-chain fatty acids, alcohols and amino acids to reduce sulfur and sulfur-containing compounds to H2S (Scanlan et al., 2009).

SRB are Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, obligate anaerobes. SRB are considered to be strictly anaerobic microorganisms, but they are also found in anoxic habitats depleted of sulfate, such as the GI tract (Rey et al., 2013). Although Hansen et al. demonstrated the lack of SRB in human gut microbiota (Hansen et al., 2011), other studies using different analytic approaches have identified SRB in the fecal microbiota of healthy adults and the distal gut mucosa (Stewart et al., 2006; Rey et al., 2013). The number of healthy individuals harboring SRB ranged from 24 to 100% (Loubinoux et al., 2002). The most frequently detected SRB from animal and human feces that are relevant to bowel colonization are flagellate Vibrio bacteria and Desulfovibrio (Scanlan et al., 2009).

For bacterial-derived H2S, little is known about the metabolic pathways involving host cellular processes. Huycke et al. showed that H2S produced by SRB in the GI tract is potentially genotoxic to the gut epithelium (Huycke and Gaskins, 2004). However, Konstantin et al. demonstrated that H2S produced by SRB acts as a cytoprotectant molecule against oxidative stress and antimicrobials by suppressing the DNA-damaging Fenton reaction and stimulating the major antioxidant enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Shatalin et al., 2011). Moreover, Devkota et al. found that SRB are positively associated with inflammation (Devkota et al., 2012): both pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling is attributed to H2S (Pitcher et al., 2000; Wallace et al., 2009). In conclusion, bacterial-derived H2S may have important roles in the GI tract, but the conclusions remain to be further explored.

Roles of H2S in the pathophysiology of IBD and CRC

IBD

The incidence of IBD and other immune-related human disorders have increased considerably over the past 50 years, matching the changes in human diet and lifestyle. The pathological roles of colonic luminal H2S and/or SRB in IBD have attracted much attention recently (Roediger et al., 1997; Wallace et al., 2009; Hirata et al., 2011). However, the viewpoint that H2S contributes to the pathogenesis of IBD remains controversial (Table 1). It has been reported previously that high levels of H2S produced by bacteria could contribute to ulcerative colitis (UC) by damaging oxidation of n-butyrate, leading to impaired barrier function (Levitt et al., 2002). However, several studies have challenged the idea for the lack of compelling evidence that H2S causes damage to colonic epithelial cells, and have demonstrated that H2S can act as a metabolic fuel for colonocytes (Goubern et al., 2007; Picton et al., 2007). Wallace et al. reported significant accumulation of H2S after induction of colitis in rats and inhibition of H2S synthesis exacerbates colitis, suggesting that H2S contributes to the resolution of experimental colitis (Wallace et al., 2009). Recently, Hirata et al. also confirmed that endogenous H2S acted as an anti-inflammatory molecule by preventing neutrophil accumulation and via its anti-oxidant ability, suggesting cytoprotective effects of H2S (Hirata et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Roles of H2S in the pathophysiology of IBD and CRC.

| Diseases | Effects of H2S | Possible pathogenesis/Epidemiologic study | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBD | Pro-inflammatory effects | Impaired oxidation of n-butyrate | Levitt et al., 2002 |

| Patients with UC had excessive SRB colonization or H2S in feces | Pitcher et al., 2000; Rowan et al., 2009 | ||

| Anti-infammatory effects | Suppression of the activation of NF-kB | Oh et al., 2006 | |

| Promotion of ucler healing in rats | Wallace et al., 2007b | ||

| Downregulation of TNF-α,IFN-γ and iNOS epression | Li et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2007a | ||

| Contribution to the resolution of experimental colitis | Wallace et al., 2009 | ||

| Acting as an antioxidant | Hirata et al., 2011 | ||

| Preventation of neutrophil accumulation and viaits anti-oxidant ability | Hirata et al., 2011 | ||

| No effects | No difference in SRB between patients with IBD and controls | Fite et al., 2004; Picton et al., 2007 | |

| CRC | Carcinogenic factor | Decrease of suifide-detoxifying enzymes | Ramasamy et al., 2006 |

| Genomic DNA damage | Attene-Ramos et al., 2007 | ||

| Stimulation of the growth and migration | Cai et al., 2010; Szabo et al., 2013; Modis et al., 2014 | ||

| Inhibition of cell apoptosis | Sen et al., 2012 | ||

| Stimulation of tumor angiogenesis and peritumoral vasodilation | Szabo et al., 2013 | ||

| Cancer suppressive factor | Reduction of cell viability | Cao et al., 2010 | |

| Inhibition of proliferation and promotion of protective autophagy | Wu et al., 2012 |

Although the functions of endogenous and exogenous H2S in IBD remains controversial, many prior studies have shown multiple effects of H2S. It can downregulate the expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ and iNOS (Li et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2007a); suppress the activation of NF-κB (Oh et al., 2006); act as an antioxidant (Hirata et al., 2011); and promote ulcer healing in rats (Wallace et al., 2007b). The colonic mucosa is endowed with an efficient H2S-detoxifying mechanism, oxidizing more than 300 μmol of H2S daily in the rat colon (Suarez et al., 1998). When the barrier breaks down, such as in severe colitis, a large amount of H2S may access the muscle layers and inhibit motility.

In addition, the contribution of bacteria-derived H2S in colitis remains unclear. An epidemiologic study revealed that patients suffering from UC had either excessive SRB colonization or excessive H2S in their feces (Pitcher et al., 2000; Rowan et al., 2009). Kleessen et al. reported variable counts of SRB from colonic mucosal specimens in patients with UC, Crohn's disease (CD) and healthy controls (Kleessen et al., 2002). However, Picton et al. found no evidence of defective enzymic detoxication of sulfide in patients with UC or CD (Picton et al., 2007). Fite et al. also confirmed that there is no disease-related difference in SRB carriage between patients with UC and controls by rectal biopsies (Fite et al., 2004).

In summary, endogenously and exogenously produced H2S in the GI tract might contribute to colitis and IBD, but there is no complete mechanistic model that explains the relationship.

CRC

CRC is the second leading cause of death from cancer and the fourth most common cancer in men and women worldwide. H2S is also implicated in CRC (Huycke and Gaskins, 2004; Cai et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Hellmich and Szabo, 2015). Although the basal expression of H2S-synthesizing enzymes in human colon tissue is relatively low (Whiteman et al., 2011), Szabo et al. observed the selective upregulation of CBS in the colon cancer tissue compared to normal mucosa tissue (Szabo et al., 2013). The expression of CBS is also upregulated in certain colon adenocarcinoma-derived cell lines (HCT-116, HT-29, and LoVo) compared with the colonic epithelial cell line. (Szabo and Hellmich, 2013) Genomic DNA damage is observed in colon cells after H2S exposure (Attene-Ramos et al., 2007). In addition, sulfide-detoxifying enzymes in the human colon are decreased in cancer tissues (Ramasamy et al., 2006).

Recently, several studies suggested that H2S regulated cell growth or death in a multitude of settings (Cai et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Medani et al., 2011; Szabo et al., 2013). Cai et al. demonstrated that H2S promoted colon cancer cell proliferation, as mentioned previously (Cai et al., 2010). However, Cao et al. demonstrated that H2S is endogenously produced in colonic tissues and that exogenously applied H2S at physiologically concentrations reduced cell viability (Cao et al., 2010). Another study showed that H2S could inhibit proliferation and promote protective autophagy in colon epithelial cells by the activation of the AMPK/ mTOR cascade (Wu et al., 2012). Previous studies have shown cell type-specific activation of MAPK by H2S, which determines the fates of cells (Cho et al., 2006; Shibuya et al., 2009a; Cao et al., 2010). These controversies may relate to the bell-shaped dose-response curve of H2S.

For tumor-produced CBS-derived H2S in CRC, Szabo et al. defined this gas as a combined autocrine and paracrine-signaling molecule (Szabo and Hellmich, 2013). As an autocrine factor, H2S stimulates the proliferation and migration of CRC cells (Cai et al., 2010; Szabo and Hellmich, 2013; Szabo et al., 2013; Modis et al., 2014). However, at higher concentrations or longer exposures to S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM), the inhibitory effects become more prominent because of cytotoxicity. Recently, Sen et al. found that the sulfhydration of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) by H2S could inhibit cell apoptosis (Sen et al., 2012). The mechanisms of the proliferative and pro-migratory effects might be the stimulation of the Akt/PI3K signaling pathway, decrease of p21 gene expression and interaction with NO (Cai et al., 2010).

As a paracrine factor, H2S might diffuse out from the tumor cell to stimulate tumor angiogenesis and peritumoral vasodilation. Szabo et al. reported that treatment of nude mice with a CBS inhibitor could attenuate the growth of patient-derived colon cancer xenografts and reduce peritumoral blood flow (Szabo et al., 2013). This study also confirmed the stimulatory role of H2S on the activity of GAPDH, indicating that H2S can affect both oxidative and glycolytic metabolism in tumor cells. Another independent study also confirmed the autocrine and paracrine functions of colon cancer-derived H2S (Yamagishi et al., 2012). Yamagishi et al. detected significant amounts of H2S inside colon cancer tissue.

Subsequent studies in nude mice bearing xenografts of either HCT116 or patient-derived tumor tissue (PDTX) extended the findings into in vivo models. Inhibition of CBS significantly reduced the growth rate of the tumor xenografts, which might be related to intratumoral mechanisms or paracrine mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment (Hellmich and Szabo, 2015). In addition, CSE can stimulate colon cancer cell proliferation, migration in vitro and tumor xenografts growth in vivo, however, the roles of CSE/H2S in colon cancer remain uncertain. Another study demonstrated that the canonical Wnt pathway can upregulate CSE expression (Fan et al., 2014).

Thus, H2S may exhibit both protective and pathological effects in the GI tract given its biphasic pharmacological characters. However, the prior studies demonstrated controversial effects of H2S and the mechanisms remain unknown.

The therapeutic potential of H2S in colonic diseases

Although limited in terms of quantity and mechanistic models, there is reasonable evidence suggesting that H2S is important for the occurrence and development of colonic diseases. The intriguing discovery that H2S governs specific protective responses against oxidative stress and antibiotics also suggested the potential therapeutic implications (Shatalin et al., 2011). We can hypothesize that H2S inhibition might be potentially applicable to inhibition of tumor blood supply and/or the hyperproliferative response in CRC. Given the particular pharmacological character of H2S, both stimulation and inhibition of H2S might have potential therapeutic applications (Szabo and Papapetropoulos, 2011).

In addition, it is noted that exposure to a relatively low level of H2S over a relatively long time period selectively inhibits cancer cell proliferation. Therefore, slow-releasing H2S donors and H2S-releasing hybrid drugs could be designed and developed as novel anticancer drugs (Wu et al., 2015). However, these possibilities are merely hypothetical at present, and the lack of wholly enzyme- and tissue-specific inhibitors of H2S has meant that controversial or contradictory conclusions have been made in previous studies.

In conclusion, H2S might play vital roles in the development of colonic diseases, and further investigations are needed to determine the proper dose range and time frame of H2S in IBD and CRC, thereby achieving optimal anti-inflammation and anti-cancer effects.

Author contributions

FG collected the references and wrote the majority of the manuscript; TY helped with the preparation and the revision of the manuscript; JH contributed to the correction of the grammar and terminology; JF contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abe K., Kimura H. (1996). The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J. Neurosci. 16, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attene-Ramos M. S., Wagner E. D., Gaskins H. R., Plewa M. J. (2007). Hydrogen sulfide induces direct radical-associated DNA damage. Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 455–459. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskar R., Bian J. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide gas has cell growth regulatory role. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 656, 5–9. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillaud F., Blachier F. (2011). Mitochondria and sulfide: a very old story of poisoning, feeding, and signaling? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 379–391. 10.1089/ars.2010.3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W. J., Wang M. J., Ju L. H., Wang C., Zhu Y. C. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide induces human colon cancer cell proliferation: role of Akt, ERK and p21. Cell Biol. Int. 34, 565–572. 10.1042/CBI20090368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q., Zhang L., Yang G., Xu C., Wang R. (2010). Butyrate-stimulated H2S production in colon cancer cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1101–1109. 10.1089/ars.2009.2915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay M., Nath N., Kodela R., Sobocki T., Metkar S., Gan Z. Y., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin inhibits the growth of leukemic Jurkat cells and modulates beta-catenin expression. Leuk. Res. 37, 1302–1308. 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiku T., Padovani D., Zhu W., Singh S., Vitvitsky V., Banerjee R. (2009). H2S biogenesis by human cystathionine gamma-lyase leads to the novel sulfur metabolites lanthionine and homolanthionine and is responsive to the grade of hyperhomocysteinemia. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11601–11612. 10.1074/jbc.M808026200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. D., Ahn N. S., Jung J. W., Yang S. R., Park J. S., Lee Y. S., et al. (2006). Critical role of the c-JunNH2-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways on sodium butyrate-induced apoptosis in DU145 human prostate cancer cells. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 15, 57–63. 10.1097/01.cej.0000195704.05246.fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coletta C., Papapetropoulos A., Erdelyi K., Olah G., Modis K., Panopoulos P., et al. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9161–9166. 10.1073/pnas.1202916109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devkota S., Wang Y., Musch M. W., Leone V., Fehlner-Peach H., Nadimpalli A., et al. (2012). Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in Il10-/- mice. Nature 487, 104–108. 10.1038/nature11225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan K., Li N., Qi J., Yin P., Zhao C., Wang L., et al. (2014). Wnt/beta-catenin signaling induces the transcription of cystathionine-gamma-lyase, a stimulator of tumor in colon cancer. Cell. Signal. 26, 2801–2808. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G., Szurszewski J. H. (2014). Carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide, and nitric oxide as signaling molecules in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 147, 303–313. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite A., Macfarlane G. T., Cummings J. H., Hopkins M. J., Kong S. C., Furrie E., et al. (2004). Identification and quantitation of mucosal and faecal desulfovibrios using real time polymerase chain reaction. Gut 53, 523–529. 10.1136/gut.2003.031245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego D., Clave P., Donovan J., Rahmati R., Grundy D., Jimenez M., et al. (2008). The gaseous mediator, hydrogen sulphide, inhibits in vitro motor patterns in the human, rat and mouse colon and jejunum. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 20, 1306–1316. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubern M., Andriamihaja M., Nubel T., Blachier F., Bouillaud F. (2007). Sulfide, the first inorganic substrate for human cells. FASEB J. 21, 1699–1706. 10.1096/fj.06-7407com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzke C., Streng T., Waldkirch E., Sigl K., Stief C., Andersson K. E., et al. (2009). Transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) activity in the human urethra–evidence for a functional role for TRPA1 in the outflow region. Eur. Urol. 55, 696–704. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E. E., Lozupone C. A., Rey F. E., Wu M., Guruge J. L., Narra A., et al. (2011). Pan-genome of the dominant human gut-associated archaeon, Methanobrevibacter smithii, studied in twins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108(Suppl. 1), 4599–4606. 10.1073/pnas.1000071108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich M. R., Coletta C., Chao C., Szabo C. (2015). The therapeutic potential of cystathionine beta-synthetase/hydrogen sulfide inhibition in cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 424–448. 10.1089/ars.2014.5933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich M. R., Szabo C. (2015). Hydrogen Sulfide and Cancer. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 230, 233–241. 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata I., Naito Y., Takagi T., Mizushima K., Suzuki T., Omatsu T., et al. (2011). Endogenous hydrogen sulfide is an anti-inflammatory molecule in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 56, 1379–1386. 10.1007/s10620-010-1461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huycke M. M., Gaskins H. R. (2004). Commensal bacteria, redox stress, and colorectal cancer: mechanisms and models. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 229, 586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashfi K. (2014). Anti-cancer activity of new designer hydrogen sulfide-donating hybrids. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 831–846. 10.1089/ars.2013.5308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashfi K., Olson K. R. (2013). Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85, 689–703. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide: its production, release and functions. Amino Acids 41, 113–121. 10.1007/s00726-010-0510-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Goto Y., Kimura H. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide increases glutathione production and suppresses oxidative stress in mitochondria. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1–13. 10.1089/ars.2008.2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleessen B., Kroesen A. J., Buhr H. J., Blaut M. (2002). Mucosal and invading bacteria in patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with controls. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 37, 1034–1041. 10.1080/003655202320378220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leschelle X., Goubern M., Andriamihaja M., Blottiere H. M., Couplan E., Gonzalez-Barroso M. D., et al. (2005). Adaptative metabolic response of human colonic epithelial cells to the adverse effects of the luminal compound sulfide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1725, 201–212. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M. D., Springfield J., Furne J., Koenig T., Suarez F. L. (2002). Physiology of sulfide in the rat colon: use of bismuth to assess colonic sulfide production. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 92, 1655–1660. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00907.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Rossoni G., Sparatore A., Lee L. C., Del Soldato P., Moore P. K. (2007). Anti-inflammatory and gastrointestinal effects of a novel diclofenac derivative. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 706–719. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden D. R., Sha L., Mazzone A., Stoltz G. J., Bernard C. E., Furne J. K., et al. (2008). Production of the gaseous signal molecule hydrogen sulfide in mouse tissues. J. Neurochem. 106, 1577–1585. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05502.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Bai X. B., Shi S., Cao Y. X. (2009). Hydrogen sulfide protects from intestinal ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 61, 207–212. 10.1211/jpp.61.02.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loubinoux J., Bronowicki J. P., Pereira I. A., Mougenel J. L., Faou A. E. (2002). Sulfate-reducing bacteria in human feces and their association with inflammatory bowel diseases. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 40, 107–112. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K., Liu Y., Zhu Q., Liu C. H., Duan J. L., Tan B. K., et al. (2011). H2S donor, S-propargyl-cysteine, increases CSE in SGC-7901 and cancer-induced mice: evidence for a novel anti-cancer effect of endogenous H2S? PLoS ONE 6:e20525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami M., Tarui T., Mitani K., Nagasawa K., Fukushima O., Okubo K., et al. (2009). Luminal hydrogen sulfide plays a pronociceptive role in mouse colon. Gut 58, 751–761. 10.1136/gut.2007.144543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medani M., Collins D., Docherty N. G., Baird A. W., O'Connell P. R., Winter D. C. (2011). Emerging role of hydrogen sulfide in colonic physiology and pathophysiology. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 1620–1625. 10.1002/ibd.21528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis K., Asimakopoulou A., Coletta C., Papapetropoulos A., Szabo C. (2013a). Oxidative stress suppresses the cellular bioenergetic effect of the 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase/hydrogen sulfide pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 433, 401–407. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis K., Coletta C., Asimakopoulou A., Szczesny B., Chao C., Papapetropoulos A., et al. (2014). Effect of S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM), an allosteric activator of cystathionine-beta-synthase (CBS) on colorectal cancer cell proliferation and bioenergetics in vitro. Nitric Oxide 41, 146–156. 10.1016/j.niox.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis K., Coletta C., Erdelyi K., Papapetropoulos A., Szabo C. (2013b). Intramitochondrial hydrogen sulfide production by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase maintains mitochondrial electron flow and supports cellular bioenergetics. FASEB J. 27, 601–611. 10.1096/fj.12-216507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis K., Panopoulos P., Coletta C., Papapetropoulos A., Szabo C. (2013c). Hydrogen sulfide-mediated stimulation of mitochondrial electron transport involves inhibition of the mitochondrial phosphodiesterase 2A, elevation of cAMP and activation of protein kinase A. Biochem Pharmacol. 86, 1311–1319. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.08.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T., Sato T., Kamoda T., Moriyama H., Kumazawa Y., Hanada N. (2014). Differential susceptibility to hydrogen sulfide-induced apoptosis between PHLDA1-overexpressing oral cancer cell lines and oral keratinocytes: role of PHLDA1 as an apoptosis suppressor. Exp. Cell Res. 320, 247–257. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A. K., Gadalla M. M., Sen N., Kim S., Mu W., Gazi S. K., et al. (2009). H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci. Signal. 2, ra72. 10.1126/scisignal.2000464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Tsugane M., Oka J., Kimura H. (2004). Hydrogen sulfide induces calcium waves in astrocytes. FASEB J. 18, 557–559. 10.1096/fj.03-1052fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning N., Zhu J., Du Y., Gao X., Liu C., Li J. (2014). Dysregulation of hydrogen sulphide metabolism impairs oviductal transport of embryos. Nat. Commun. 5, 4107. 10.1038/ncomms5107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh G. S., Pae H. O., Lee B. S., Kim B. N., Kim J. M., Kim H. R., et al. (2006). Hydrogen sulfide inhibits nitric oxide production and nuclear factor-kappaB via heme oxygenase-1 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41, 106–119. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patacchini R., Santicioli P., Giuliani S., Maggi C. A. (2005). Pharmacological investigation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) contractile activity in rat detrusor muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 509, 171–177. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton R., Eggo M. C., Langman M. J., Singh S. (2007). Impaired detoxication of hydrogen sulfide in ulcerative colitis? Dig. Dis. Sci. 52, 373–378. 10.1007/s10620-006-9529-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher M. C., Beatty E. R., Cummings J. H. (2000). The contribution of sulphate reducing bacteria and 5-aminosalicylic acid to faecal sulphide in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 46, 64–72. 10.1136/gut.46.1.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupo E., Pla A. F., Avanzato D., Moccia F., Cruz J. E., Tanzi F., et al. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide promotes calcium signals and migration in tumor-derived endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 1765–1773. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy S., Singh S., Taniere P., Langman M. J., Eggo M. C. (2006). Sulfide-detoxifying enzymes in the human colon are decreased in cancer and upregulated in differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291, G288–G296. 10.1152/ajpgi.00324.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey F. E., Gonzalez M. D., Cheng J., Wu M., Ahern P. P., Gordon J. I. (2013). Metabolic niche of a prominent sulfate-reducing human gut bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13582–13587. 10.1073/pnas.1312524110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E., Moore J., Babidge W. (1997). Colonic sulfide in pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 42, 1571–1579. 10.1023/A:1018851723920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose P., Moore P. K., Ming S. H., Nam O. C., Armstrong J. S., Whiteman M. (2005). Hydrogen sulfide protects colon cancer cells from chemopreventative agent beta-phenylethyl isothiocyanate induced apoptosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 3990–3997. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.3990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudsari L. C., West J. L. (2015). Studying the influence of angiogenesis in in vitro cancer model systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 97, 250–259. 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan F. E., Docherty N. G., Coffey J. C., O'Connell P. R. (2009). Sulphate-reducing bacteria and hydrogen sulphide in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis. Br. J. Surg. 96, 151–158. 10.1002/bjs.6454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan P. D., Shanahan F., Marchesi J. R. (2009). Culture-independent analysis of desulfovibrios in the human distal colon of healthy, colorectal cancer and polypectomized individuals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 69, 213–221. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen N., Paul B. D., Gadalla M. M., Mustafa A. K., Sen T., Xu R., et al. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide-linked sulfhydration of NF-kappaB mediates its antiapoptotic actions. Mol. Cell 45, 13–24. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatalin K., Shatalina E., Mironov A., Nudler E. (2011). H2S: a universal defense against antibiotics in bacteria. Science 334, 986–990. 10.1126/science.1209855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya N., Mikami Y., Kimura Y., Nagahara N., Kimura H. (2009a). Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J. Biochem. 146, 623–626. 10.1093/jb/mvp111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya N., Tanaka M., Yoshida M., Ogasawara Y., Togawa T., Ishii K., et al. (2009b). 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 703–714. 10.1089/ars.2008.2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Padovani D., Leslie R. A., Chiku T., Banerjee R. (2009). Relative contributions of cystathionine beta-synthase and gamma-cystathionase to H2S biogenesis via alternative trans-sulfuration reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22457–22466. 10.1074/jbc.M109.010868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. A., Chadwick V. S., Murray A. (2006). Carriage, quantification, and predominance of methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria in faecal samples. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43, 58–63. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez F., Furne J., Springfield J., Levitt M. (1998). Production and elimination of sulfur-containing gases in the rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. 274, G727–G733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C., Coletta C., Chao C., Modis K., Szczesny B., Papapetropoulos A., et al. (2013). Tumor-derived hydrogen sulfide, produced by cystathionine-beta-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12474–12479. 10.1073/pnas.1306241110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C., Hellmich M. R. (2013). Endogenously produced hydrogen sulfide supports tumor cell growth and proliferation. Cell Cycle 12, 2915–2916. 10.4161/cc.26064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C., Papapetropoulos A. (2011). Hydrogen sulphide and angiogenesis: mechanisms and applications. Br. J. Pharmacol. 164, 853–865. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01191.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C., Ransy C., Modis K., Andriamihaja M., Murghes B., Coletta C., et al. (2014). Regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetic function by hydrogen sulfide. Part I. Biochemical and physiological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2099–2122. 10.1111/bph.12369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao B. B., Liu S. Y., Zhang C. C., Fu W., Cai W. J., Wang Y., et al. (2013). VEGFR2 functions as an H2S-targeting receptor protein kinase with its novel Cys1045-Cys1024 disulfide bond serving as a specific molecular switch for hydrogen sulfide actions in vascular endothelial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 448–464. 10.1089/ars.2012.4565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. L., Caliendo G., Santagada V., Cirino G., Fiorucci S. (2007a). Gastrointestinal safety and anti-inflammatory effects of a hydrogen sulfide-releasing diclofenac derivative in the rat. Gastroenterology 132, 261–271. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. L., Dicay M., McKnight W., Martin G. R. (2007b). Hydrogen sulfide enhances ulcer healing in rats. FASEB J. 21, 4070–4076. 10.1096/fj.07-8669com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. L., Vong L., McKnight W., Dicay M., Martin G. R. (2009). Endogenous and exogenous hydrogen sulfide promotes resolution of colitis in rats. Gastroenterology 137, 569–578.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Qiu B., Han L., Feng G., Hu Y., Chang L., et al. (2012). Effect of precursor and preparation method on manganese based activated carbon sorbents for removing H2S from hot coal gas. J. Hazard. Mater. 213–214, 184–192. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.01.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. (2009). Hydrogen sulfide: a new EDRF. Kidney Int. 76, 700–704. 10.1038/ki.2009.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. (2012). Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 92, 791–896. 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M., Le Trionnaire S., Chopra M., Fox B., Whatmore J. (2011). Emerging role of hydrogen sulfide in health and disease: critical appraisal of biomarkers and pharmacological tools. Clin. Sci. 121, 459–488. 10.1042/CS20110267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M., Li L., Rose P., Tan C. H., Parkinson D. B., Moore P. K. (2010). The effect of hydrogen sulfide donors on lipopolysaccharide-induced formation of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1147–1154. 10.1089/ars.2009.2899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Si W., Wang M., Lv S., Ji A., Li Y. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide in cancer: friend or foe? Nitric Oxide 50, 38–45. 10.1016/j.niox.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. C., Wang X. J., Yu L., Chan F. K., Cheng A. S., Yu J., et al. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide lowers proliferation and induces protective autophagy in colon epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 7:e37572. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi K., Onuma K., Chiba Y., Yagi S., Aoki S., Sato T., et al. (2012). Generation of gaseous sulfur-containing compounds in tumour tissue and suppression of gas diffusion as an antitumour treatment. Gut 61, 554–561. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Wu L., Jiang B., Yang W., Qi J., Cao K., et al. (2008). H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science 322, 587–590. 10.1126/science.1162667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]