Abstract

To date, the considerable body of research on predictors of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has conceptualized NSSI as a unitary construct despite the fact that NSSI can exist in many forms (e.g., hitting, cutting, burning). The goal of the present study is to examine differential prediction of forms of NSSI. Specifically, we examined trait aggression as a predictor of more aggressive forms of NSSI (i.e., hitting). We hypothesized that higher trait aggression would differentiate those who engaged in hitting forms of NSSI from those who did not, whereas other factors (i.e., emotion regulation and trait anger) would serve as a non-specific predictor of NSSI. We also hypothesized that higher trait aggression would be related to lifetime frequency of hitting NSSI, but not other forms of NSSI, whereas emotion regulation and anger would act as predictors of other forms of NSSI. To test these hypotheses, a large sample of young adults completed measures of trait aggression, trait anger, emotion regulation, and NSSI behaviors. Results were generally in line with our hypotheses. Higher levels of trait aggression differentiated those who engaged in hitting NSSI from those who did not and was also associated with greater frequency of hitting NSSI. These results imply that different factors predict different forms of NSSI and that NSSI may be best examined as a multi-faceted construct.

Keywords: Non-suicidal self-injury, aggression, anger, emotion regulation, NSSI, forms

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the intentional damaging of body tissue without the intent of dying (Klonsky, 2007). Nearly six percent of the general population is estimated to have engaged in NSSI at some point in their lifetime (Klonsky, 2011). Even higher rates have been found in college students, with studies reporting from nearly 15% NSSI engagement in samples (Heath, Toste, Nedecheva, & Charlebois, 2008; Whitlock, et al., 2011) to over 35% engagement in samples (Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002). In addition to the relatively high prevalence, NSSI is a strong correlate of other adverse behavior, including drug use (Hilt, Nock, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2008) and suicide attempts (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006). NSSI exists in several forms including cutting, biting, burning, hitting oneself or objects, and severe scratching. Individuals tend to prefer one (or several) forms over others. Studies of latent classes find that the tendency to use one form over another differentiates types of self-injurers. For example, Klonsky & Olino (2008) found that a preference towards aggressive forms of NSSI, such as hitting oneself, is descriptive of one class of self-injurers, whereas a preference towards more common forms of NSSI, such as self-cutting, are descriptive of another class.

Despite the body of research suggesting that preference towards certain forms of NSSI are indicators of different types of self-injurers, the vast majority of research on NSSI risk is concerned with NSSI as a unitary construct. Such research ignores the possibility of examining the specificity of risk factors to specific forms of NSSI. This is especially relevant given that Klonsky and Olino (2008) have found important differences between groups of individuals with preferences towards specific NSSI forms. For example, individuals who engage in self-hitting tend to have lower levels of depressive symptoms than those who engage in other forms of NSSI. Given that depression is a strong predictor of NSSI when NSSI is examined as a unitary construct (Marshall, Tilton-Weaver, & Stattin, 2013), Klonsky & Olino’s (2008) findings could imply that self-hitting is predicted by a factor other than depression. One such variable might be aggression. Individuals who are high in trait aggression are much more likely to engage in violence towards others (Loeber & Hay, 1997; Tremblay & Belchevski, 2004) including fighting, (i.e., hitting and punching; Bettencourt, Talley, Arlin, & Valentine, 2006). Thus, behaviors such as hitting and punching others could be considered part of an aggressive individual’s behavioral repertoire. That is, aggressive people are familiar with aggressive behaviors such as hitting. Thus, it might be that when an aggressive individual engages in NSSI, they default to these behaviors with which they are familiar.

There is some precedent for aggression predicting NSSI when measured as a unitary construct. Trait aggression is linked with the tendency to engage in NSSI (Haavisto et al., 2005; Hillbrand, Krystal, Sharpe, & Foster, 1994; Tang et al., 2013). At clinical levels, aggression is a component of intermittent explosive disorder, which is associated with increased prevalence of NSSI (McCloskey, Ben-Zeev, Lee, & Coccaro, 2008). In adolescents, aggression is found to be a distal predictor of NSSI, which is mediated by emotion regulation (Adrian, Zeman, Erdley, Lisa, & Sim, 2010). Other studies have found that a family history of aggression distinguishes those who have engaged in NSSI from those who have not (Deliberto & Nock, 2008). Finally, NSSI and suicidal behavior are strongly correlated (Nock et al., 2006), and several studies have found that trait aggression predicts suicidal behavior (Greening, Stoppelbein, Luebbe, & Fite, 2010; Zhang et al., 2012). Thus, there is clear support for trait aggression as a predictor of NSSI and factors related to NSSI. However, all previous studies of aggression and NSSI have examined NSSI as a unitary construct and did not examine it in relationship to specific forms of NSSI. It is anticipated that aggression will be most strongly related to more “aggressive” forms of NSSI, such as hitting oneself or an object, because aggressive people are likely used to engaging in aggressive, violent behaviors. Thus, when engaging in NSSI aggressive individuals would be expected to turn to more aggressive means of self-injury.

The present study

The present study examined the role of trait aggression as a differential predictor of NSSI forms. Specifically, it was hypothesized that trait aggression would differentiate those who engage in hitting as a form of NSSI from those who engage in other forms (e.g., cutting). In addition to exploring the role of aggression as a differential predictor of NSSI forms, the current study explored two other variables that could serve as comparison variables: trait anger and general emotion regulation difficulties. Emotion regulation is arguably the factor that is most often studied in relationship to NSSI (see Jacobson & Gould, 2007 for review) and angry mood inductions are often used in experimental NSSI paradigms (Weinberg & Klonsky, 2012). Thus, it was hypothesized that poorer emotion regulation and higher levels of anger might act as non-specific risk factors for NSSI, differentiating individuals who have never engaged in NSSI from those who have engaged in either hitting or non-hitting forms of NSSI.

Method

Participants

Participants were 2,290 young adults (62.2% female) from a large, diverse, urban university in the northeast. The average age was 20.79 years (SD = 3.21 years). The sample was 60.8% Caucasian, 13.8% Asian, 13.2% African American, and the rest self-identified with another race or as multiple races. Approximately 27% of the participants had engaged in at least one form of NSSI. Further demographic information as a function of NSSI group is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics by NSSI group

| NSSI Groups

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Total (n = 2290) | No NSSI (n = 1666) | Hitting only (n = 98) | Non-hitting only (n = 365) | Hitting + non-hitting (n = 161) | F/χ2 |

| Age (SD) | 20.79 (3.21) | 20.84a (3.33) | 20.54a (2.33) | 20.74a (3.02) | 20.60a (2.93) | 0.78 |

| Female gender (%) | 1424 (62.2%) | 1006a (60.4%) | 33b (33.6%) | 278a (76.5%) | 108a (67.4%) | 99.16*** |

| Race (%) | 16.40* | |||||

| Caucasian | 1393 (60.8%) | 991a (59.5%) | 63a (64.3%) | 231a (63.3%) | 108a (67.1%) | |

| African American | 302 (13.2%) | 240a (14.4%) | 9a (9.2%) | 44 a (12.1%) | 9b (5.6%) | |

| Other | 595 (26.0%) | 435a (26.1%) | 26a (26.5%) | 90a (24.7%) | 44a (27.3%) | |

Note. Columns in each row with different subscripts are significantly different at p < .05 ***, p < .001 *, p < .05.

Procedure

On a secure website, participants completed self-report measures as part of a larger, IRB-approved study on aggression. Participants received course-required research credit for their participation.

Measures

Aggression

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) is a 29-item self-report measure of trait aggression that encompasses verbal aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. Higher scores on all scales equal higher levels of aggression. In the present study, the BPAQ had acceptable internal consistency (a = .84).

Anger

The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory 2 - Trait Subscale (STAXI-T; Spielberger, 1999) is a 10-item self-report measure of trait anger. Higher scores represent higher levels of anger. The STAXI-T has strong utility in determining groups of individuals with clinically relevant levels of anger (Deffenbacher et al., 1996). In the present study, the STAXI-T had acceptable internal consistency (a = .85).

Emotion regulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure of emotion regulation difficulties. The measure assesses various indices of emotion regulation difficulties (e.g., lack of emotional awareness, impulse control difficulties) and can be summed to create an overall global index of emotion dysregulation. In the present study, we used the full scale global emotion dysregulation score, which had excellent internal consistency (a = .93).

NSSI

The Forms and Functions of Self Injury (FAFSI; Jenkins, Conner, & Alloy, 2011) is a measure of the forms, functions, and frequency of NSSI. The FAFSI assesses the following NSSI forms: cutting, carving, scratching, burning, swallowing poison, pinching, poking with a needle or other sharp object, biting, pulling hair, inserting objects under skin, and punching self. Participants are asked if they engage in each form of NSSI as well as how many times they have engaged in each form. For the present study, we grouped punching self and banging head as “hitting” NSSI and all other forms as “other” NSSI.

Analytic Strategy

Our primary hypotheses rest on a distinction between hitting and non-hitting forms of NSSI. To establish this distinction, we first conducted preliminary factor analyses. Our a priori hypothesis was that hitting forms of NSSI would fall on a distinct factor from other forms of NSSI. We had no a priori hypothesis about the factor structure of the other forms of NSSI. Thus, we conducted both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). First, we conducted an EFA of only the non-hitting forms of NSSI to determine the potential factor structure of these variables. Second, we conducted a CFA to support the idea that hitting and non-hitting forms of NSSI would be supported as separate factors. We utilized the results of the prior EFA to inform the factor structure of non-hitting NSSI. As will be discussed, the non-hitting forms of NSSI clustered on to three factors. Thus, we created a second-order factor of non-hitting NSSI, which consisted of these three factors. This method was appropriate because EFA alone did not allow for the testing of a theoretically relevant, a priori model and CFA alone did not allow for the non-specific hypotheses regarding the structure of non-hitting NSSI to be included. These analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013).

EFA in Mplus involves specifying a number of factors starting with one factor and continuing to add factors until a non-significant chi-square model fit statistic is obtained, indicating that the model fits the data. Thus, the number of factors is determined by the lowest number of factors specified that results in a non-significant chi-square. We conducted the EFA using Varimax rotation; with a minimal factor loading of .40 to determine which variables fell on which factor. CFA in Mplus involves specifying which variables load on to which factor and examining a chi-square difference test. We utilized the modification indices function to suggest additional paths that could be added to the model.

To test our first primary hypothesis that individuals who engaged in hitting forms of NSSI (i.e., self-hitting, banging head) would have higher levels of aggression, but not necessarily higher levels of anger or emotion dysregulation, we conducted a series of ANOVAs with NSSI status (i.e., no NSSI, hitting NSSI only, non-hitting NSSI only, hitting + non-hitting NSSI) as the grouping variable. Prior to conducting our analyses, we conducted a Levene’s test of equality to verify that we were not violating the assumption of homogeneity of variances across groups (which was a strong possibility given the unequal cell sizes). The only variable in which this assumption was not met was the DERS score (F = 3.44, p = .016). Although log transforming the DERS scores did correct for this issue (F = 2.51, p = .051), the interpretation of the results for the transformed and untransformed analyses were the same. Thus, for ease of understanding and consistency across measures, we report the untransformed analyses.

To test our second primary hypothesis that higher levels of aggression would be uniquely associated with more frequent engagement in hitting NSSI and unassociated with other NSSI, we conducted a path analysis in Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). In this analysis, BPAQ, STAXI-T, and DERS scores (i.e., the exogenous variables) were simultaneously regressed on to frequency of hitting and non-hitting NSSI (i.e., the endogenous variables). Covariances were specified between all exogenous variables as they were correlated at the bivariate level and measured at the same time. Given that the endogenous variables measured frequency of a specific action, they were specified as count variables. Because they were count variables, error terms were not estimated (see Muthén & Muthén, 2013 for more information).

Results

Preliminary analyses

When examining bivariate correlations, BPAQ, STAXI-T, and DERS scores were all positively correlated. BPAQ scores were positively correlated with STAXI-T scores (r = .59, p < .001) and DERS scores (r = .42, p < .001). STAXI-T and DERS scores were also positively correlated (r = .41, p < .001). Table 1 shows the sample demographics by NSSI group. There were no age differences. Participants were more likely to be female in the no NSSI, other NSSI, and hitting/other NSSI groups, and more likely to be male in the hitting only group. The only race difference was that African American participants were less likely to be in the hitting and other NSSI group than the other groups.

When examining frequency of NSSI acts by NSSI risk group, participants in the hitting only group engaged in hitting an average of 9.97 times in their lifetime (SD = 18.23). Those who engaged in other NSSI engaged in non-hitting NSSI an average of 24.06 times in their lifetime (SD = 53.40). Those who engaged in both hitting and other forms of NSSI engaged in hitting NSSI an average of 17.17 times in their lifetime (SD = 34.15) and other NSSI an average of 51.11 times in their lifetime (SD = 164.59). Thus, individuals who engaged in both forms of NSSI engaged in more hitting NSSI than those who engaged in hitting NSSI only (F = 5.56, p = .019), and more other NSSI than those who engaged in non-hitting NSSI only (F = 11.38, p = .001). This suggests that those who engage in multiple forms of NSSI also engage in more NSSI acts.

Factor analysis of NSSI frequency variables

We first conducted an EFA to determine the factor structure of the frequency of non-hitting NSSI variables. The most parsimonious acceptable solution involved three factors (x2 (1)= 17.69, p = .126, RMSEA = .023). Cutting (.88) and burning (.94) self loaded on to one factor; carving (.31), poisoning (.78), and scratching (.34) self loaded on to another factor; and pinching (.65), pulling hair (.41), and biting (.45) self loaded on to the final factor. Poking self did not load on to any factor and was removed from further analyses. We note that only 8% of the sample engaged in poking at all, and nearly all of those who had indicated they poked themselves (~90%) had done so less than five times in their lifetime.

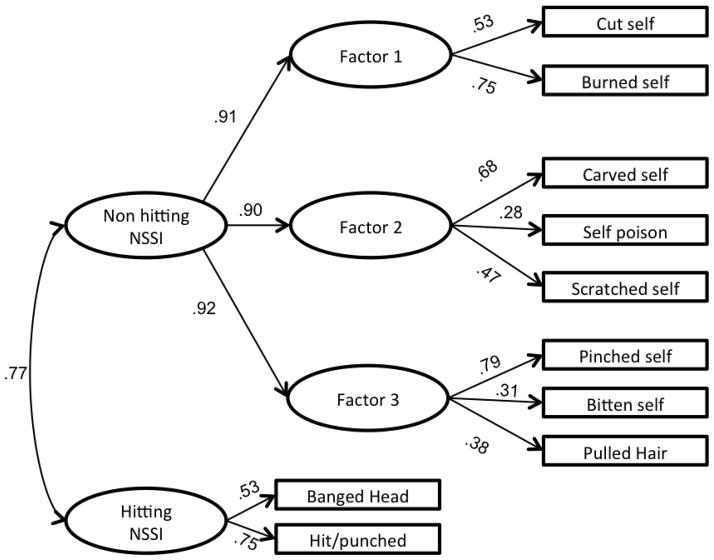

We next used the results of the EFA to construct our CFA. The three non-hitting NSSI factors were loaded onto a higher-order “non-hitting NSSI” factor and the two hitting forms of NSSI (banging head and hitting/punching self) were loaded on to a “hitting NSSI factor.” According to Hu & Bentler’s (1999) recommendation (RMSEA < .06, SRMR < .08), the model had acceptable fit: (x2 (31) = 43.34, p = .069, RMSEA = .021, SRMR = .042). This diagram of the CFA can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of frequency of NSSI behaviors

Note. All solid lines are significant at p < .001; The covariance between biting self and banging head are not shown for clarity of results (r = .14, p < .001).

Hypothesis 1: Aggression identifies those who engage in hitting forms of NSSI

Table 2 shows the results of a series of one-way ANOVAs to determine if the BPAQ, STAXI-T, and DERS were able to distinguish between groups of individuals who had never engaged in NSSI, had engaged in hitting NSSI only, had engaged in other (non-hitting) NSSI only, or had engaged in both hitting and non-hitting forms of NSSI. The mean BPAQ score for the no NSSI group was significantly lower than all other groups, representing medium to large effect sizes (ds = 0.37 – 0.67). When examining the groups of individuals who did engage in NSSI, the individuals who engaged in hitting NSSI only and hitting + non-hitting NSSI did not significantly differ from each other, but did have significantly higher BPAQ scores than either the no NSSI group or the non-hitting NSSI only group. A medium effect size was observed for both the difference between hitting only and non-hitting NSSI only groups (d = 0.30), and hitting + non-hitting NSSI and other NSSI only (d = 0.25) groups. This finding would suggest that the BPAQ serves to distinguish those who have engaged in NSSI from those who have not. It also suggests that the BPAQ distinguishes those who have engaged in hitting NSSI from those who have not.

Table 2.

Results of ANOVA analyses comparing no NSSI, hitting only, non-hitting only, and hitting + non-hitting groups

| NSSI Groups

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | No NSSI | Hitting only | Non-hitting | Hitting + non-hitting | F |

| Aggression (BPAQ) | 66.72a | 77.68b | 72.62c | 76.70b | 40.22*** |

| Anger (STAXI - T) | 16.27a | 18.89b | 18.13b | 18.45b | 66.17*** |

| Emotion regulation (DERS) | 80.39a | 89.11b | 90.31b | 97.62c | 66.17*** |

Note. BPAQ = Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; STAXI-T = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Trait Subscale; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Columns in each row with different subscripts are significantly different at p < .05 ***, p < .001.

The mean STAXI-T score for the no NSSI group was significantly lower than all other groups, representing medium to large effect sizes (ds = 0.43 – 0.75), There was, however, no significant difference observed between any of the groups that engaged in NSSI. This finding would suggest that the while the STAXI-T does distinguish between those who have and have not engaged in NSSI, it does not distinguish the actual forms of NSSI.

The mean DERS score for the no NSSI group was significantly lower than all other groups (ds = 0.42 – 0.73). The mean DERS score of the hitting + non-hitting NSSI only group was significantly higher than any of the other NSSI groups, with medium to large effect sizes (ds = 0.31 – 0.76). The hitting and non-hitting NSSI groups did not significantly differ on the DERS. Thus, this would suggest that the DERS only distinguishes between those who have and have not engaged in NSSI and among those who have engaged in any form of NSSI.

Hypothesis 2: Aggression identifies frequency of hitting NSSI

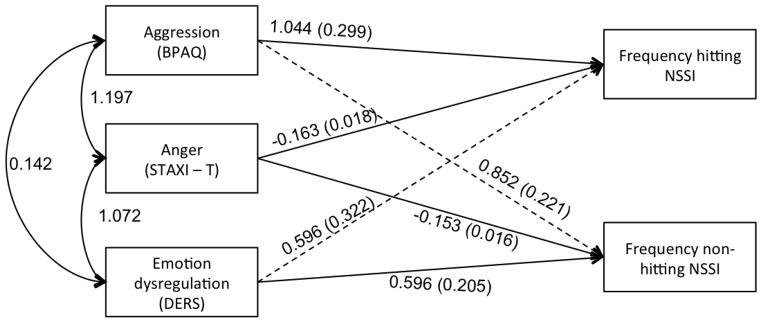

Figure 1 displays results of a path analysis testing the second study hypothesis1. As can be seen in the figure, BPAQ scores were positively related to frequency of hitting NSSI, but not to non-hitting NSSI forms. DERS scores were positively related to frequency of non-hitting NSSI, but were unrelated to hitting NSSI. These two findings are consistent with our hypothesis and support the differential prediction of forms of NSSI. Aggression is only associated with hitting NSSI, while emotion dysregulation is only associated with non-hitting NSSI.

Interestingly, STAXI-T scores showed a weak, but significant, negative relationship with both frequency of hitting and non-hitting NSSI. These relationships might be due to the effect of negative suppression (Maassen & Bakker, 2001). Negative suppression occurs when inclusion of a variable that is strongly correlated with another variable changes the sign of the relationship between that variable and another variable. In other words, negative suppression occurs when the predicting ability that one variable has on another, left over after controlling for a third variable, is somehow different than that within the original relationship. This would be the case for the relationship of STAXI-T scores with both frequency of hitting and non-hitting NSSI. BPAQ and STAXI-T scores were strongly correlated with each other, thus the inclusion of BPAQ scores in the path model changed the relationship between STAXI-T and frequency of hitting NSSI. Additionally, DERS and STAXI-T scores were strongly correlated with each other, thus the inclusion of DERS scores in the path model changed the relationship between STAXI-T and frequency of non-hitting NSSI.

Given that the STAXI-T scores created a situation of negative suppression, we also analyzed a model that did not include the STAXI-T. Because typical nested model tests are not available when using count variables as outcomes, we utilized the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) as an index of relative model fit. Lower BIC scores indicate a better model fit. The original model with the STAXI-T included had better relative model fit (BIC = 71688.34) than the new model without STAXI-T (BIC = 75864.08). Therefore, we can assume that the removal of the STAXI-T worsens model fit and thus it is not discussed further.

Discussion

Despite the considerable research dedicated to the exploration of NSSI, most research has examined NSSI as a unitary construct, ignoring the possible variation in risk factors to specific forms of NSSI. The present study is the first to our knowledge to explore differential predictors of forms of NSSI. Specifically, we examined the role of trait aggression as a predictor of hitting forms of NSSI (e.g., self-hitting). Our first broad hypothesis was that higher levels of trait aggression would distinguish those who had engaged in hitting NSSI from those who had not, while other related factors (i.e., anger and emotion dysregulation) would not. It was expected that these factors would instead act as non-specific risk factors for NSSI in general. The results of the study were mostly in line with our hypotheses. We found that higher levels of trait aggression distinguished those who engaged in hitting NSSI from those who only engaged in non-hitting NSSI and no NSSI at all. There was no difference between those who had engaged in just hitting NSSI or both hitting and non-hitting NSSI.

The findings regarding emotion dysregulation were less straightforward. We found that emotion dysregulation distinguished the no NSSI group from all other groups and the hitting + non-hitting NSSI group from the other two NSSI groups (i.e., hitting only and non-hitting only). It might be that engaging in multiple forms of NSSI is an indicator of more severe NSSI. Thus, higher emotion dysregulation predicts more severe NSSI. Indeed, studies of latent classes of self-injurers in college students find that individuals who engage in multiple forms of NSSI represent a more severe level of NSSI (Klonsky & Olino, 2008). This would suggest that while emotion regulation does not serve to distinguish between forms of NSSI, it may serve as an index of overall NSSI severity.

Our second hypothesis was that trait aggression would predict more frequent engagement in hitting NSSI above and beyond anger and emotion dysregulation. We also predicted that trait aggression would not predict frequency of non-hitting NSSI. Our results were generally in line with this hypothesis. Greater trait aggression was associated with more frequent engagement in hitting NSSI and was unassociated with frequency of engagement in non-hitting NSSI. Greater emotion dysregulation was associated with more frequent engagement in non-hitting NSSI and was unassociated with frequency of hitting NSSI. These results suggest that trait aggression is a unique, differential predictor of hitting NSSI, while emotion dysregulation is a unique predictor of non-hitting NSSI. As discussed earlier, anger demonstrated a negative suppression effect on frequency of hitting and non- hitting NSSI when entered into the same model as emotion dysregulation and trait aggression. This might be a result of anger being a weaker predictor of NSSI when divided between hitting and non- hitting forms. Anger might be especially important when examining functions rather than forms of NSSI. A common function of NSSI is to relieve anger. Thus, individuals with higher levels of trait anger might be more likely to engage in NSSI to relieve anger. Future research is needed that addresses this idea.

In sum, we found that aggression has a unique relationship with hitting forms of NSSI. This can be contrasted to factors such as emotion regulation that appear to have a more general relationship with NSSI. While aggressive individuals appear to engage in more hitting NSSI, individuals with poorer emotion regulation appear more likely to engage in any form of NSSI. At the greatest levels of emotion regulation deficits, individuals appear to engage in more severe forms of NSSI. A more broad implication of these findings is that it is important to examine NSSI as a multifaceted, rather than unitary, construct. Future research may find that other factors distinguish other forms of NSSI. Our study represented only one possible division of forms of NSSI and there are many others possible. For example, attention seeking, a trait present in some personality disorders (e.g., histrionic), might be more strongly related to forms of NSSI that are outwardly visible (e.g., cutting on the lower arm).

There are several strengths and limitations that should be acknowledged. Limitations of the present study involve the use of cross sectional, self-report data in an unselected sample. Future studies using interview measures of NSSI in a prospective, clinical sample are needed. Strengths of the present study include the use of a large, ethnically diverse sample and advanced statistical modeling techniques.

Compared to other college student samples (e.g., Whitlock, 2011), a somewhat larger proportion of our sample had indicated that they engaged in NSSI at some point in their lives (27%). Although this number represents a greater proportion than some previous studies, it should be noted that it is smaller than the proportions reported in other studies (e.g., Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002). Thus, engagement of NSSI in college samples varies widely compared to reports based on the general population. In addition, our study focused on aggressive behaviors and it may have attracted more aggressive individuals who were more likely to engage in NSSI.

Finally, our findings have several clinical implications. First, our findings suggest that it is important to assess for a wide range of NSSI behaviors in a clinical setting, especially among aggressive individuals. Given that aggressive individuals are less likely to engage in more “typical,” non-hitting forms of NSSI (e.g., cutting) and more likely to engage in hitting forms of NSSI that might not be typically acknowledged as NSSI. Screening for multiple forms of NSSI would allow clinicians to avoid missing crucial indicators of self-injurious behavior. Our findings also suggest that it is important to focus on reducing aggression in treatment of individuals who engage in hitting forms of NSSI. There is a notable absence of effective treatments that specifically target any form of NSSI (Nock, Teper, & Hollander, 2007). There are many effective treatments for aggressive behavior (Del Vecchio & O’Leary, 2004). Thus, aggression might prove a useful target for individuals who engage in hitting forms of NSSI, especially in the absence of effective NSSI treatment.

Figure 2.

Path analysis predicting frequency of NSSI behaviors

Note. BPAQ = Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; STAXI-T = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Trait Subscale; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Unstandardized coefficients reported; standard error in parenthesis. All solids lines are significant at p < .05, dotted lines are not significant.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by NIMH Grant R01MH086525 to Dr. Michael McCloskey.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Lisa L, Sim L. Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;39:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencort A, Talley A, Benjamin AJ, Valentine J. Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:751–777. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, Thwaites GA, Lynch RS, Baker DA, Stark RS, Eiswerth-Cox L. State–trait anger theory and the utility of the trait anger scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43:131–148. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.43.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio T, O’Leary KD. Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliberto TL, Nock MK. An exploratory study of correlates, onset, and offset of non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12:219–231. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:128–140. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Luebbe A, Fite PJ. Aggression and the risk for suicidal behaviors among children. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:337–345. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavisto A, Sourander A, Multimäki P, Parkkola K, Santalahti P, Helenius H, Almqvist F. Factors associated with ideation and acts of deliberate self-harm among 18-year-old boys. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:912–921. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath N, Toste J, Nedecheva T, Charlebois A. An Examination of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Among College Students. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2008;30:137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hillbrand M, Krystal JH, Sharpe KS, Foster HG. Clinical predictors of self-mutilation in hospitalized forensic patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Nock MK, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adolescents rates, correlates, and preliminary test of an interpersonal model. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:455–469. doi: 10.1177/0272431608316604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CM, Gould M. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11:129–147. doi: 10.1080/13811110701247602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA, Brodsky B, Ellis SP, Stanley B, Mann JJ. Aggressiveness, not impulsiveness or hostility, distinguishes suicide attempters with major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1779. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1981–1986. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Olino TM. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:22–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Hay D. Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen GH, Bakker AB. Suppressor variables in path models definitions and interpretations. Sociological Methods & Research. 2001;30:241–270. doi: 10.1177/0049124101030002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SK, Tilton-Weaver LC, Stattin H. Non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms during middle adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:1234–1242. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Ben-Zeev D, Lee R, Coccaro EF. Prevalence of suicidal and self-injurious behavior among subjects with intermittent explosive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2008;158(2):248–250. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nock M, Joiner T, Gordon K, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein M. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Teper R, Hollander M. Psychological treatment of self-injury among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63:1081–1089. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2. Orlando, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Ma Y, Guo Y, Ahmed NI, Yu Y, Wang J. Association of aggression and non-suicidal self injury: A school-based sample of adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay PF, Belchevski M. Did the instigator intend to provoke? A key moderator in the relation between trait aggression and aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 2004;30:409–424. doi: 10.1002/ab.20027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Klonsky ED. The effects of self-injury on acute negative arousal: A laboratory simulation. Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36(2):242–254. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9233-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Purington A, Eckenrode J, Barreira P, Baral Abrams G, Knox K. Nonsuicidal Self-injury in a College Population: General Trends and Sex Differences. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59:691–698. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.529626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Roberts RE, Liu Z, Meng X, Tang J, Sun L, Yu Y. Hostility, physical aggression and trait anger as predictors for suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents: A school-based study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]