Abstract

The Pediatric Growth Chart (2007) is used as a standard reference to evaluate weight and height percentiles of Korean children and adolescents. Although several previous studies provided a useful reference range of newborn birth weight (BW) by gestational age (GA), the BW reference analyzed by sex and plurality is not currently available. Therefore, we aimed to establish a national reference range of neonatal BW percentiles considering GA, sex, and plurality of newborns in Korea. The raw data of all newborns (470,171 in 2010, 471,265 in 2011, and 484,550 in 2012) were analyzed. Using the Korean Statistical Information Service data (2010–2012), smoothed percentile curves (3rd–97th) by GA were created using the lambda-mu-sigma method after exclusion and the data were distinguished by all live births, singleton births, and multiple births. In the entire cohort, male newborns were heavier than female newborns and singletons were heavier than twins. As GA increased, the difference in BW between singleton and multiples increased. Compared to the previous data published 10 years ago in Korea, the BW of newborns 22–23 gestational weeks old was increased, whereas that of others was smaller. Other countries' data were also compared and showed differences in BW of both singleton and multiple newborns. We expect this updated data to be utilized as a reference to improve clinical assessments of newborn growth.

Keywords: Birth Weight, Singleton, Multiple Birth, Newborn, Gestational Age

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide data of the significance of newborn birth weight (BW) have been studied since the 1970s (1). By analyzing newborn BW by gestational age (GA), we can evaluate fetal growth, intrauterine growth restriction (which has high perinatal mortality), and epidemiologic data comparing fetal growth and chronic adulthood disease. The newborn's condition immediately after birth can be predicted accordingly. From the long-term perspective, a nation's public health system could be established (2,3). Since 2000, several studies have provided a reference range of newborn BW by GA in Korea. However, some have limitations, including: an insufficient sample size based on 18,427 newborns in 2003; the Korean Statistical Information Service data (2001-2003, 1,509,763 persons; 2000–2004, 2,585,516 persons) were based on the previous 10 years; and recent data based on Korean Statistical Information Service data (2008-2012) did not exclude the common error showing the double humped curve that appears most frequently in the big data analysis and made only singleton references (4,5,6,7).

It has recently become popular in Korea to marry at a later age, which could increase the number of elderly gravida and high-risk pregnancies, eventually increasing premature birth rates. In addition, in vitro fertilization is associated with an increase in multiple pregnancies. There has been a recent increase in inter-racial infants in Korea (8,9,10). These changes have a strong influence on BW. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to establish a new national reference range of neonatal BW percentiles considering the GA, sex, and plurality of newborns in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this study, we used the Korean Statistical Information Service data (2010.01–2012.12) of a total of 1,425,986 newborns. The raw data of all newborns (470,171 in 2010, 471,265 in 2011, and 484,550 in 2012) were analyzed. Our results were based on 1,422,890 births after exclusions. Newborns with unknown BW (n = 2,100), unknown GA (n = 2,514), or a GA < 22 weeks (n = 73) or > 42 weeks (n = 297) were excluded. Some of the exclusions (n = 1,888) are duplicated. The GA referred to the interval, in completed weeks, between the first day of the mother's last menstrual period and the delivery date. Therefore, the GA of 40 weeks means 40 weeks plus 0–6 days. BW was measured to the nearest 10 g.

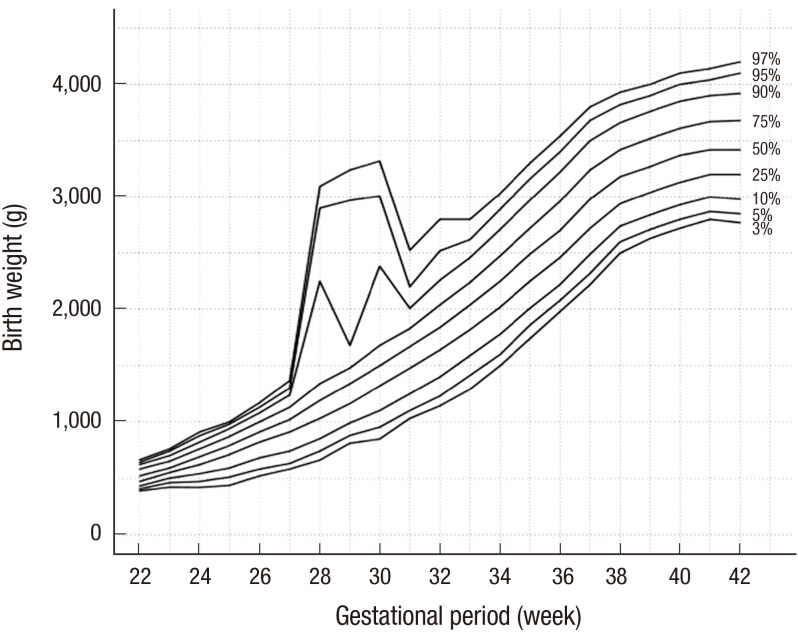

Fig. 1 represented the percentile curves of BW for GA based on the Korean Statistical Information Service's raw data after exclusions. It included the estimated error data of 28–32 weeks' gestation. The histogram of BW of 28–32 weeks' gestation before smoothing showed a double humped curve as reported by Lee (6). Both humps are normal distributions with the estimated truth (left) and error values (right).

Fig. 1.

Percentile curves [3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th] of birth weight for gestational age based on the raw data. %, percentile.

This report used the Finite Gaussian mixture model, which is a convex combination of two or more probability density functions that was enabled to correct the error and represent the normal distribution curve (11,12). The lambda-mu-sigma (LMS) method, a way of obtaining normalized growth curves, was developed by Cole and Green (13), and it was expected that the data could be normalized using a powerful transformation that changes raw data into a standard deviation Z-score. The LMS method calculates asymmetrical parameters by the Box-Cox transformation to be normal. Here it estimated the three parameters of the Box-Cox transformation of the measurement distribution (14). The three parameters are constrained to change smoothly as the covariate changes.

The LMS methods were analyzed by Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Moreover, all graphs were made using GraphPad Prism software (ver. 6.05, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The SPSS for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the data input, processing, and analysis. The smoothed data were represented by the BW percentile curves. The curves appeared at intervals of one week by gestation and separated into all live births, singlet births, and multiple births. We also constructed separate curves and tables for male and female newborns for the 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentiles from 22 to 42 completed weeks based on smoothed estimated curves.

Classification according to BW are as follows: extremely low birth weight (ELBW, BWs < 1,000 g) infants, very low birth weight (VLBW, BWs < 1,500 g) infants, low birth weight (LBW, BWs < 2,500 g) infants, normal birth weight (NBW, 2,500 ≤ BWs ≤ 3,999 g) infants, high birth weight (HBW, BWs > 4,000 g) infants.

RESULTS

Of all infants born between 2010 and 2012, there were 733,980 and 692,006 boys and girls, respectively, showing a gender ratio of 1.06, and there were 1,381,088 and 42,314 singleton and multiple births, respectively (Table 1). After assessing BW and GA for the 3-year period, extremely low BW infants and very low BW infants accounted for 0.24% and 0.62%, respectively, while premature birth infants born at < 37 weeks' gestation accounted for 6% of the total infant population (Table 2). Initially, data on 2,726 infants whose BW and GAs were unclear as well as those of 370 infants whose GA was ≤ 21 weeks or ≥ 43 weeks were excluded from the raw data of the National Statistical Office of South Korea. Subsequently, error data of 28–32 weeks' gestation were removed, followed by smoothing with the LMS method.

Table 1. Number of infants divided by infant sex and multiplicity before exclusions, 2010–2012.

| Demography parameters | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 242,901 | 242,121 | 248,958 | 733,980 |

| Female | 227,270 | 229,144 | 235,592 | 692,006 |

| Male/female ratio | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Multiplicity* | ||||

| Singlet | 455,309 | 457,171 | 468,608 | 1,381,088 |

| Multiple | 12,841 | 13,852 | 15,621 | 42,314 |

| Multiple birth rate† | 27.3 | 29.4 | 32.2 | 29.7 |

*Except unknown multiplicity.

†Per 1,000 live births.

Table 2. Distribution of births by birth weight and gestational period before exclusions, 2010-2012.

| Birth parameters | No. (%) of birth |

|---|---|

| By birth weight | |

| ELBW infants | 3,394 (0.24) |

| VLBW infants | 8,789 (0.62) |

| LBW infants | 74,054 (5.19) |

| NBW infants | 1,300,902 (91.23) |

| HBW infants | 48,930 (3.43) |

| Unknown | 2,100 (0.15) |

| Total | 1,425,986 (100) |

| By gestational period | |

| Preterm infants | 86,365 (6.06) |

| Term infants | 1,333,242 (93.5) |

| Post-term infants | 3,865 (0.27) |

| Unknown | 2,514 (0.18) |

| Total | 1,425,986 (100) |

ELBW, extremely low birth weight; VLBW, very low birth weight; LBW, low birth weight; NBW, normal birth weight; HBW, high birth weight.

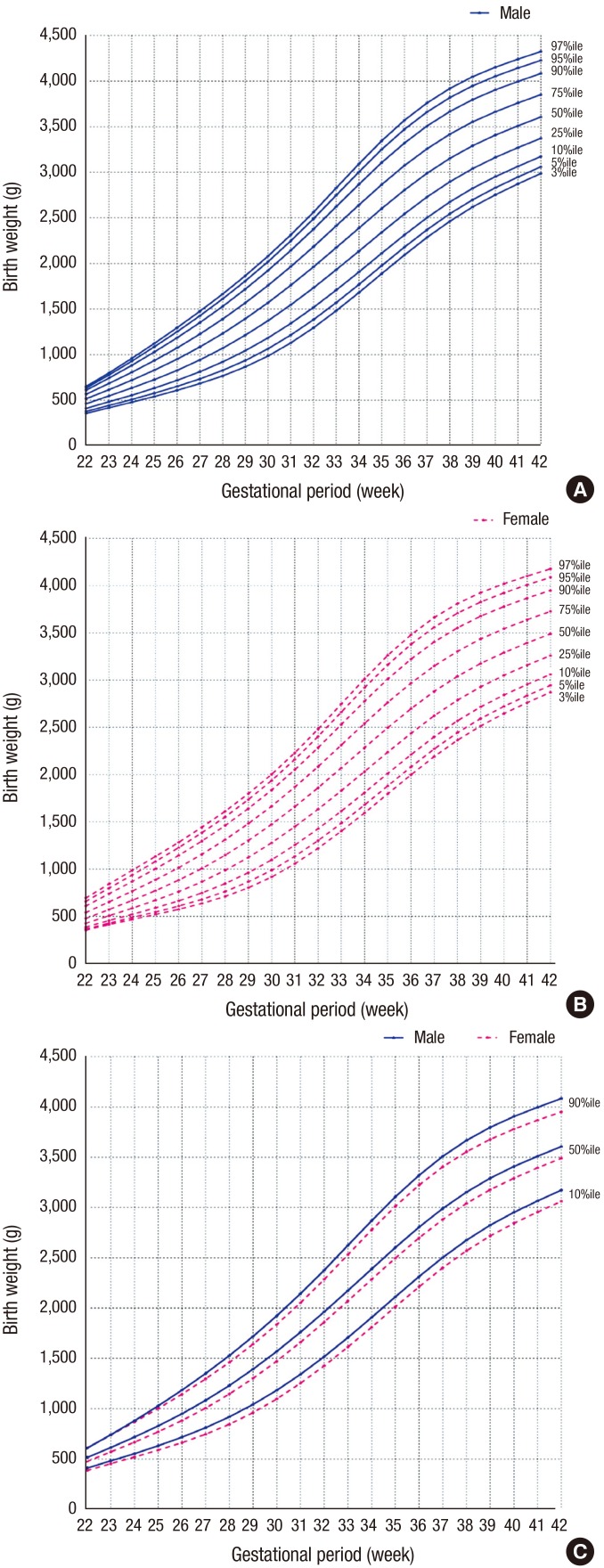

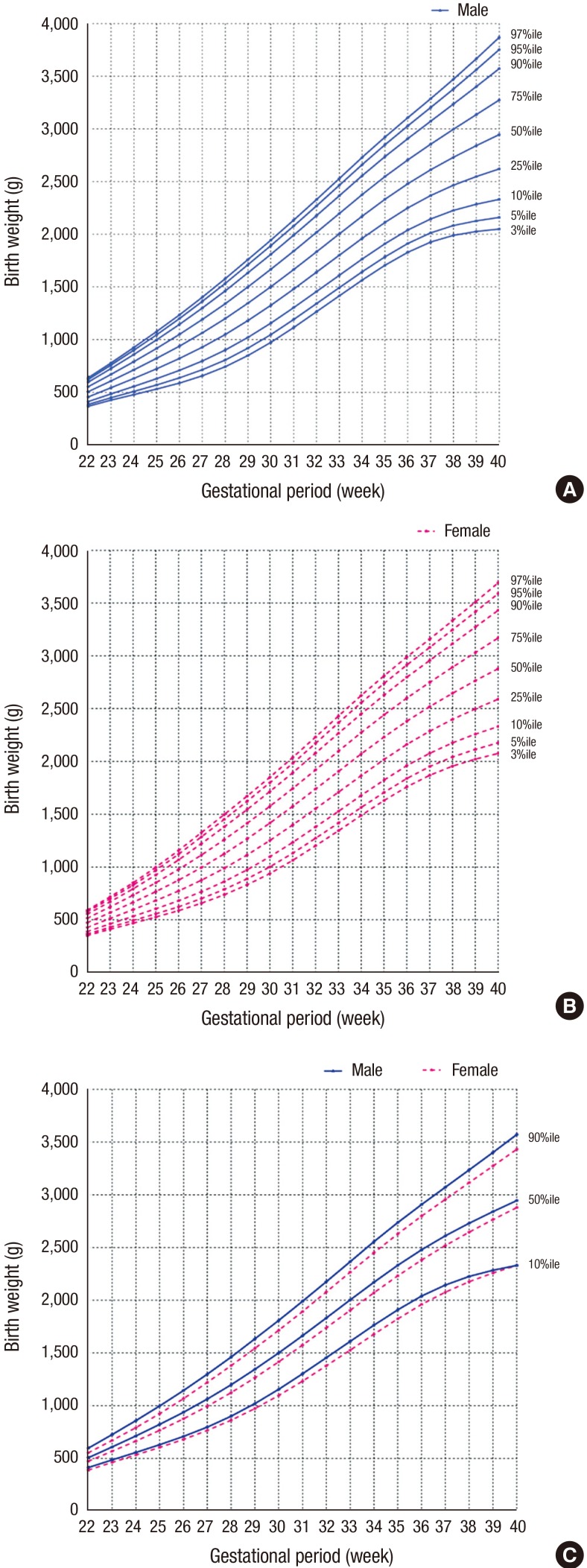

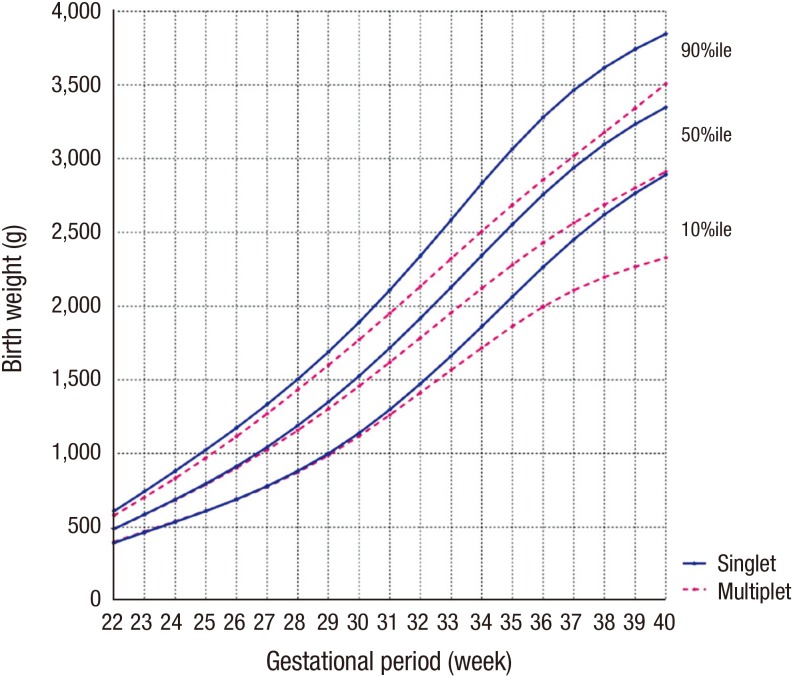

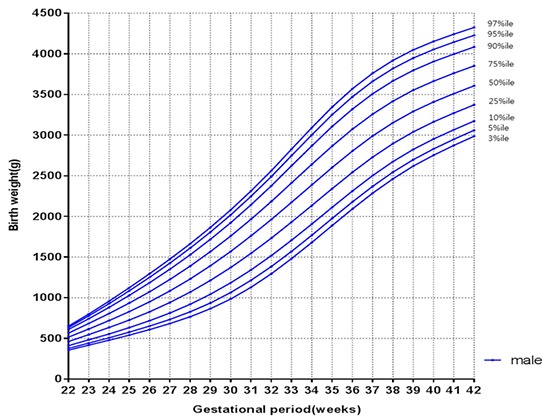

All infants were classified according to gestation regardless of singleton or multiple birth, and data on the 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentiles are presented in Tables 3 (male) and 4 (female). Data on boys and girls born by singleton and multiple births are presented in Tables 5678. The BW percentile curves after smoothing singleton births are presented in Fig. 2A and 2B, while the BW percentile curves of multiple births are presented in Fig. 3A and 3B. In the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile graphs of singleton births, boys showed higher BW than those of girls in the total infant graphs at each GA (Fig. 2C). Multiple-birth infants also showed a pattern similar to that of singleton-birth infants. However, BW of boys and girls close to 40 weeks' gestation in the 10th percentile graph tended to be similar (Fig. 3C). When graphs of singleton- and multiple-birth male and female infants overlapped by GA, more differences in BW were seen between multiple- and singleton-birth infants as GA increased (Fig. 4).

Table 3. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentiles of birth weight (g) for 22–42 weeks' gestational age for all male infants.

| GP | No. | 3rd Percentile |

5th Percentile |

10th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

90th Percentile |

95th Percentile |

97th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 65 | 356 | 374 | 402 | 448 | 499 | 550 | 596 | 623 | 641 |

| 23 | 157 | 418 | 441 | 476 | 535 | 602 | 669 | 730 | 767 | 791 |

| 24 | 285 | 479 | 507 | 550 | 624 | 707 | 793 | 871 | 918 | 949 |

| 25 | 325 | 541 | 575 | 628 | 717 | 819 | 923 | 1,017 | 1,074 | 1,112 |

| 26 | 434 | 606 | 647 | 712 | 819 | 940 | 1,061 | 1,171 | 1,236 | 1,279 |

| 27 | 547 | 677 | 728 | 805 | 932 | 1,072 | 1,210 | 1,334 | 1,407 | 1,454 |

| 28 | 744 | 758 | 819 | 909 | 1,057 | 1,216 | 1,371 | 1,507 | 1,587 | 1,638 |

| 29 | 793 | 857 | 926 | 1,030 | 1,197 | 1,374 | 1,544 | 1,692 | 1,779 | 1,835 |

| 30 | 1,032 | 974 | 1,052 | 1,167 | 1,351 | 1,545 | 1,730 | 1,891 | 1,985 | 2,045 |

| 31 | 1,325 | 1,114 | 1,197 | 1,321 | 1,518 | 1,728 | 1,929 | 2,103 | 2,205 | 2,271 |

| 32 | 1,944 | 1,273 | 1,359 | 1,488 | 1,697 | 1,922 | 2,139 | 2,330 | 2,442 | 2,514 |

| 33 | 2,728 | 1,448 | 1,535 | 1,668 | 1,888 | 2,127 | 2,362 | 2,571 | 2,695 | 2,775 |

| 34 | 5,236 | 1,637 | 1,725 | 1,861 | 2,087 | 2,339 | 2,591 | 2,817 | 2,952 | 3,040 |

| 35 | 9,516 | 1,836 | 1,924 | 2,060 | 2,292 | 2,552 | 2,816 | 3,057 | 3,202 | 3,297 |

| 36 | 22,408 | 2,038 | 2,126 | 2,262 | 2,494 | 2,759 | 3,030 | 3,280 | 3,431 | 3,530 |

| 37 | 67,989 | 2,237 | 2,323 | 2,458 | 2,688 | 2,953 | 3,226 | 3,479 | 3,633 | 3,735 |

| 38 | 188,256 | 2,422 | 2,506 | 2,638 | 2,864 | 3,125 | 3,395 | 3,647 | 3,801 | 3,902 |

| 39 | 210,907 | 2,588 | 2,670 | 2,798 | 3,018 | 3,273 | 3,538 | 3,785 | 3,937 | 4,038 |

| 40 | 174,916 | 2,735 | 2,814 | 2,938 | 3,152 | 3,400 | 3,659 | 3,901 | 4,051 | 4,150 |

| 41 | 40,834 | 2,867 | 2,943 | 3,063 | 3,270 | 3,511 | 3,763 | 4,001 | 4,147 | 4,244 |

| 42 | 1,677 | 2,992 | 3,066 | 3,181 | 3,381 | 3,614 | 3,859 | 4,091 | 4,234 | 4,329 |

GP, gestational period.

Table 4. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentile birth weight (g) for 22–42 weeks' gestation for all female infants.

| GP | No. | 3rdPercentile | 5thPercentile | 10thPercentile | 25thPercentile | 50thPercentile | 75thPercentile | 90thPercentile | 95thPercentile | 97thPercentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 62 | 349 | 361 | 381 | 419 | 467 | 523 | 582 | 622 | 650 |

| 23 | 123 | 409 | 425 | 452 | 500 | 563 | 635 | 710 | 760 | 795 |

| 24 | 240 | 467 | 488 | 521 | 583 | 661 | 750 | 841 | 901 | 943 |

| 25 | 328 | 523 | 549 | 592 | 668 | 764 | 871 | 978 | 1,047 | 1,095 |

| 26 | 379 | 582 | 614 | 667 | 761 | 875 | 1,000 | 1,122 | 1,200 | 1,252 |

| 27 | 493 | 646 | 686 | 751 | 864 | 998 | 1,140 | 1,275 | 1,359 | 1,415 |

| 28 | 674 | 720 | 770 | 848 | 981 | 1,134 | 1,291 | 1,437 | 1,525 | 1,583 |

| 29 | 643 | 810 | 869 | 961 | 1,114 | 1,285 | 1,457 | 1,612 | 1,705 | 1,766 |

| 30 | 892 | 919 | 987 | 1,090 | 1,261 | 1,449 | 1,635 | 1,801 | 1,900 | 1,964 |

| 31 | 1,013 | 1,051 | 1,125 | 1,238 | 1,423 | 1,627 | 1,828 | 2,008 | 2,114 | 2,183 |

| 32 | 1,561 | 1,204 | 1,281 | 1,400 | 1,598 | 1,817 | 2,035 | 2,231 | 2,348 | 2,423 |

| 33 | 2,198 | 1,371 | 1,451 | 1,575 | 1,784 | 2,018 | 2,254 | 2,469 | 2,598 | 2,682 |

| 34 | 4,213 | 1,553 | 1,635 | 1,762 | 1,979 | 2,226 | 2,479 | 2,711 | 2,851 | 2,943 |

| 35 | 7,659 | 1,746 | 1,828 | 1,958 | 2,181 | 2,437 | 2,702 | 2,948 | 3,098 | 3,197 |

| 36 | 18,226 | 1,943 | 2,026 | 2,156 | 2,381 | 2,642 | 2,914 | 3,167 | 3,323 | 3,426 |

| 37 | 56,714 | 2,137 | 2,220 | 2,350 | 2,574 | 2,835 | 3,108 | 3,363 | 3,520 | 3,624 |

| 38 | 163,877 | 2,319 | 2,400 | 2,528 | 2,749 | 3,006 | 3,274 | 3,526 | 3,681 | 3,784 |

| 39 | 197,141 | 2,484 | 2,563 | 2,688 | 2,904 | 3,155 | 3,417 | 3,662 | 3,813 | 3,913 |

| 40 | 184,907 | 2,627 | 2,705 | 2,827 | 3,038 | 3,282 | 3,536 | 3,774 | 3,921 | 4,017 |

| 41 | 47,541 | 2,756 | 2,832 | 2,951 | 3,157 | 3,394 | 3,641 | 3,871 | 4,012 | 4,106 |

| 42 | 1,888 | 2,878 | 2,952 | 3,068 | 3,269 | 3,499 | 3,738 | 3,961 | 4,097 | 4,188 |

GP, gestational period.

Table 5. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentile birth weight (g) for 22-42 weeks' gestation for singleton-birth male infants.

| GP | No. | 3rd Percentile |

5th Percentile |

10th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

90th Percentile |

95th Percentile |

97th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 27 | 356 | 378 | 411 | 462 | 516 | 566 | 610 | 635 | 652 |

| 23 | 82 | 417 | 443 | 483 | 547 | 616 | 684 | 743 | 777 | 800 |

| 24 | 162 | 478 | 508 | 555 | 634 | 720 | 806 | 882 | 928 | 958 |

| 25 | 205 | 541 | 577 | 633 | 726 | 830 | 935 | 1,030 | 1,087 | 1,124 |

| 26 | 278 | 609 | 652 | 718 | 828 | 951 | 1,074 | 1,186 | 1,252 | 1,296 |

| 27 | 375 | 683 | 734 | 812 | 942 | 1,084 | 1,225 | 1,351 | 1,426 | 1,475 |

| 28 | 538 | 766 | 827 | 920 | 1,070 | 1,232 | 1,390 | 1,529 | 1,611 | 1,664 |

| 29 | 604 | 865 | 936 | 1,043 | 1,213 | 1,394 | 1,568 | 1,719 | 1,808 | 1,865 |

| 30 | 793 | 985 | 1,065 | 1,184 | 1,372 | 1,571 | 1,760 | 1,924 | 2,020 | 2,081 |

| 31 | 1,003 | 1,128 | 1,215 | 1,342 | 1,546 | 1,761 | 1,966 | 2,143 | 2,247 | 2,313 |

| 32 | 1,338 | 1,295 | 1,384 | 1,518 | 1,733 | 1,963 | 2,184 | 2,377 | 2,491 | 2,563 |

| 33 | 1,974 | 1,482 | 1,571 | 1,708 | 1,931 | 2,174 | 2,412 | 2,623 | 2,748 | 2,828 |

| 34 | 3,830 | 1,681 | 1,770 | 1,907 | 2,136 | 2,389 | 2,642 | 2,869 | 3,005 | 3,093 |

| 35 | 7,105 | 1,888 | 1,976 | 2,112 | 2,342 | 2,602 | 2,865 | 3,106 | 3,251 | 3,345 |

| 36 | 17,178 | 2,093 | 2,179 | 2,313 | 2,543 | 2,805 | 3,074 | 3,321 | 3,472 | 3,571 |

| 37 | 60,877 | 2,287 | 2,371 | 2,503 | 2,730 | 2,990 | 3,259 | 3,509 | 3,662 | 3,762 |

| 38 | 186,011 | 2,464 | 2,546 | 2,675 | 2,897 | 3,153 | 3,419 | 3,667 | 3,820 | 3,920 |

| 39 | 210,574 | 2,619 | 2,698 | 2,824 | 3,040 | 3,291 | 3,553 | 3,797 | 3,948 | 4,048 |

| 40 | 174,769 | 2,753 | 2,830 | 2,952 | 3,163 | 3,408 | 3,664 | 3,905 | 4,053 | 4,152 |

| 41 | 40,813 | 2,873 | 2,948 | 3,066 | 3,271 | 3,510 | 3,761 | 3,997 | 4,144 | 4,241 |

| 42 | 1,674 | 2,987 | 3,060 | 3,174 | 3,373 | 3,606 | 3,851 | 4,084 | 4,228 | 4,324 |

GP, gestational period.

Table 6. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentile birth weight (g) for 22-42 weeks' gestation for singleton-birth female infants.

| GP | No. | 3rd Percentile |

5th Percentile |

10th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

90th Percentile |

95th Percentile |

97th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 28 | 354 | 366 | 387 | 426 | 477 | 540 | 609 | 658 | 694 |

| 23 | 69 | 412 | 428 | 455 | 506 | 572 | 652 | 738 | 798 | 841 |

| 24 | 139 | 467 | 488 | 522 | 586 | 669 | 766 | 869 | 938 | 987 |

| 25 | 230 | 520 | 546 | 590 | 670 | 771 | 886 | 1,003 | 1,080 | 1,133 |

| 26 | 270 | 575 | 609 | 664 | 762 | 883 | 1,015 | 1,145 | 1,228 | 1,284 |

| 27 | 329 | 636 | 679 | 747 | 866 | 1,007 | 1,156 | 1,297 | 1,385 | 1,443 |

| 28 | 505 | 710 | 763 | 846 | 987 | 1,147 | 1,311 | 1,461 | 1,553 | 1,612 |

| 29 | 496 | 802 | 865 | 962 | 1,124 | 1,303 | 1,481 | 1,641 | 1,736 | 1,798 |

| 30 | 661 | 916 | 988 | 1,098 | 1,278 | 1,474 | 1,666 | 1,837 | 1,938 | 2,003 |

| 31 | 743 | 1,056 | 1,135 | 1,254 | 1,449 | 1,661 | 1,869 | 2,052 | 2,161 | 2,231 |

| 32 | 1,069 | 1,220 | 1,302 | 1,427 | 1,634 | 1,861 | 2,085 | 2,286 | 2,405 | 2,482 |

| 33 | 1,466 | 1,401 | 1,485 | 1,614 | 1,830 | 2,071 | 2,313 | 2,531 | 2,662 | 2,748 |

| 34 | 2,888 | 1,595 | 1,680 | 1,810 | 2,033 | 2,285 | 2,542 | 2,777 | 2,920 | 3,013 |

| 35 | 5,316 | 1,797 | 1,881 | 2,013 | 2,238 | 2,497 | 2,764 | 3,012 | 3,163 | 3,262 |

| 36 | 13,186 | 1,999 | 2,082 | 2,212 | 2,437 | 2,698 | 2,969 | 3,223 | 3,379 | 3,481 |

| 37 | 49,484 | 2,191 | 2,272 | 2,401 | 2,623 | 2,881 | 3,151 | 3,405 | 3,561 | 3,664 |

| 38 | 161,640 | 2,365 | 2,444 | 2,570 | 2,788 | 3,041 | 3,306 | 3,555 | 3,709 | 3,811 |

| 39 | 196,832 | 2,516 | 2,594 | 2,717 | 2,930 | 3,177 | 3,436 | 3,678 | 3,828 | 3,927 |

| 40 | 184,778 | 2,646 | 2,723 | 2,843 | 3,051 | 3,292 | 3,544 | 3,779 | 3,924 | 4,020 |

| 41 | 47,525 | 2,762 | 2,837 | 2,955 | 3,159 | 3,394 | 3,639 | 3,868 | 4,009 | 4,102 |

| 42 | 1,882 | 2,871 | 2,945 | 3,061 | 3,260 | 3,490 | 3,729 | 3,951 | 4,088 | 4,178 |

GP, gestational period.

Table 7. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentile birth weight (g) for 22-40 weeks' gestation for multiple-birth male infants.

| GP | No. | 3rd Percentile |

5th Percentile |

10th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

90th Percentile |

95th Percentile |

97th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 19 | 368 | 386 | 413 | 457 | 506 | 554 | 597 | 622 | 638 |

| 23 | 41 | 426 | 449 | 485 | 544 | 608 | 670 | 725 | 758 | 779 |

| 24 | 76 | 478 | 509 | 556 | 632 | 713 | 791 | 859 | 899 | 925 |

| 25 | 77 | 531 | 570 | 629 | 723 | 822 | 916 | 998 | 1,045 | 1,076 |

| 26 | 111 | 588 | 637 | 708 | 821 | 938 | 1,049 | 1,144 | 1,199 | 1,234 |

| 27 | 147 | 657 | 714 | 797 | 928 | 1,063 | 1,190 | 1,299 | 1,362 | 1,402 |

| 28 | 185 | 742 | 806 | 900 | 1,047 | 1,198 | 1,340 | 1,462 | 1,533 | 1,578 |

| 29 | 173 | 848 | 918 | 1,020 | 1,180 | 1,345 | 1,500 | 1,634 | 1,711 | 1,760 |

| 30 | 228 | 973 | 1,046 | 1,155 | 1,325 | 1,501 | 1,667 | 1,809 | 1,892 | 1,944 |

| 31 | 316 | 1,114 | 1,190 | 1,303 | 1,480 | 1,665 | 1,840 | 1,991 | 2,078 | 2,134 |

| 32 | 545 | 1,264 | 1,341 | 1,456 | 1,640 | 1,833 | 2,017 | 2,176 | 2,269 | 2,328 |

| 33 | 743 | 1,415 | 1,493 | 1,611 | 1,801 | 2,003 | 2,197 | 2,366 | 2,465 | 2,529 |

| 34 | 1,396 | 1,564 | 1,643 | 1,764 | 1,960 | 2,171 | 2,376 | 2,555 | 2,661 | 2,729 |

| 35 | 2,401 | 1,705 | 1,786 | 1,910 | 2,112 | 2,332 | 2,547 | 2,737 | 2,850 | 2,922 |

| 36 | 5,206 | 1,828 | 1,912 | 2,039 | 2,249 | 2,479 | 2,706 | 2,908 | 3,028 | 3,106 |

| 37 | 7,081 | 1,925 | 2,012 | 2,145 | 2,367 | 2,612 | 2,855 | 3,073 | 3,203 | 3,287 |

| 38 | 2,197 | 1,989 | 2,082 | 2,226 | 2,465 | 2,731 | 2,997 | 3,236 | 3,379 | 3,472 |

| 39 | 301 | 2,026 | 2,127 | 2,284 | 2,547 | 2,841 | 3,136 | 3,402 | 3,562 | 3,666 |

| 40 | 120 | 2,048 | 2,159 | 2,331 | 2,620 | 2,946 | 3,275 | 3,573 | 3,753 | 3,870 |

GP, gestational period.

Table 8. Smoothed 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 90th, 95th, and 97th percentile birth weight (g) for 22-40 weeks' gestation for multiple-birth female infants.

| GP | No. | 3rd Percentile |

5th Percentile |

10th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

90th Percentile |

95th Percentile |

97th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 15 | 350 | 365 | 389 | 429 | 472 | 515 | 554 | 577 | 591 |

| 23 | 34 | 410 | 430 | 461 | 512 | 567 | 621 | 670 | 698 | 717 |

| 24 | 65 | 467 | 493 | 532 | 595 | 664 | 732 | 792 | 827 | 850 |

| 25 | 80 | 525 | 556 | 603 | 681 | 766 | 850 | 924 | 968 | 996 |

| 26 | 79 | 587 | 623 | 680 | 773 | 875 | 977 | 1,068 | 1,122 | 1,157 |

| 27 | 144 | 657 | 700 | 765 | 874 | 994 | 1,113 | 1,221 | 1,285 | 1,326 |

| 28 | 149 | 737 | 787 | 862 | 987 | 1,124 | 1,259 | 1,380 | 1,451 | 1,498 |

| 29 | 135 | 830 | 887 | 973 | 1,113 | 1,265 | 1,413 | 1,544 | 1,622 | 1,672 |

| 30 | 216 | 938 | 1,001 | 1,097 | 1,251 | 1,416 | 1,576 | 1,716 | 1,799 | 1,851 |

| 31 | 260 | 1,063 | 1,131 | 1,233 | 1,399 | 1,575 | 1,745 | 1,894 | 1,982 | 2,038 |

| 32 | 479 | 1,201 | 1,272 | 1,379 | 1,552 | 1,739 | 1,920 | 2,079 | 2,172 | 2,232 |

| 33 | 725 | 1,343 | 1,416 | 1,527 | 1,709 | 1,905 | 2,097 | 2,266 | 2,366 | 2,430 |

| 34 | 1,317 | 1,489 | 1,564 | 1,678 | 1,866 | 2,071 | 2,273 | 2,451 | 2,557 | 2,626 |

| 35 | 2,332 | 1,630 | 1,707 | 1,824 | 2,018 | 2,231 | 2,441 | 2,629 | 2,740 | 2,812 |

| 36 | 5,028 | 1,760 | 1,839 | 1,960 | 2,161 | 2,382 | 2,601 | 2,798 | 2,914 | 2,990 |

| 37 | 7,217 | 1,869 | 1,951 | 2,077 | 2,287 | 2,519 | 2,750 | 2,957 | 3,080 | 3,160 |

| 38 | 2,213 | 1,955 | 2,042 | 2,176 | 2,399 | 2,646 | 2,893 | 3,115 | 3,248 | 3,334 |

| 39 | 287 | 2,021 | 2,114 | 2,258 | 2,498 | 2,765 | 3,032 | 3,273 | 3,418 | 3,511 |

| 40 | 100 | 2,076 | 2,176 | 2,331 | 2,590 | 2,880 | 3,171 | 3,433 | 3,591 | 3,694 |

GP, gestational period.

Fig. 2.

Smoothed percentile curves of birth weight distribution by gestational age for singlet (A) male, (B) female, and (C) male + female populations. %ile, percentile.

Fig. 3.

Smoothed percentile curves of birth weight distribution by gestational age for twin (A) male, (B) female, and (C) male + female populations. %ile, percentile.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of singleton and multiple percentile curves of birth weight by gestational age for male and female infants. %ile, percentile.

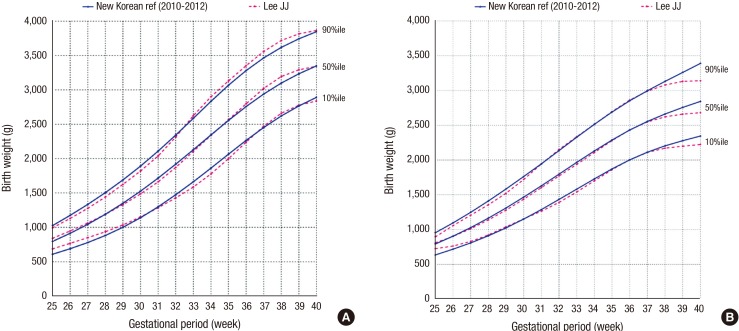

When BW of singleton-birth male and female infants were compared with other data in South Korea from 2000–2004 for the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile graphs (6), the patterns were similar for 30–32 weeks, whereas the 10th percentile graph of the present study showed a lower mean BW before 30 weeks' gestation (Fig. 5A). In contrast, when twin male and female infants were compared in the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles, BW increased after 37 weeks' gestation compared to the data of 2000–2004 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of (A) singleton, (B) twin birth weight percentile curves for male and female infants among different study of Korean populations. %ile, percentile.

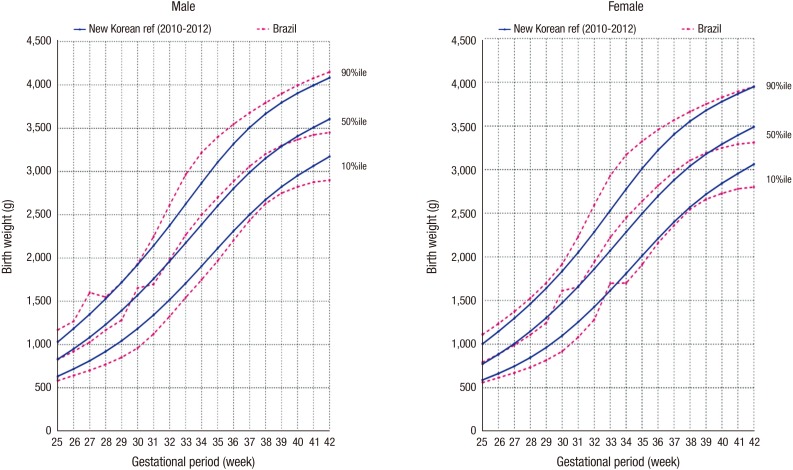

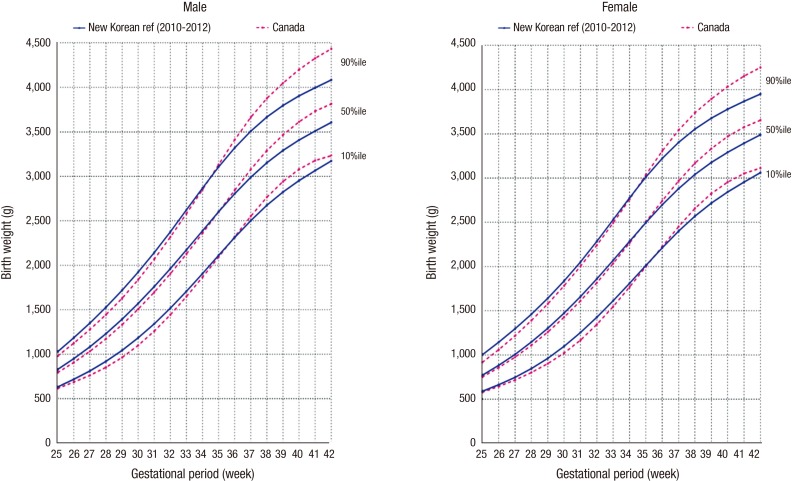

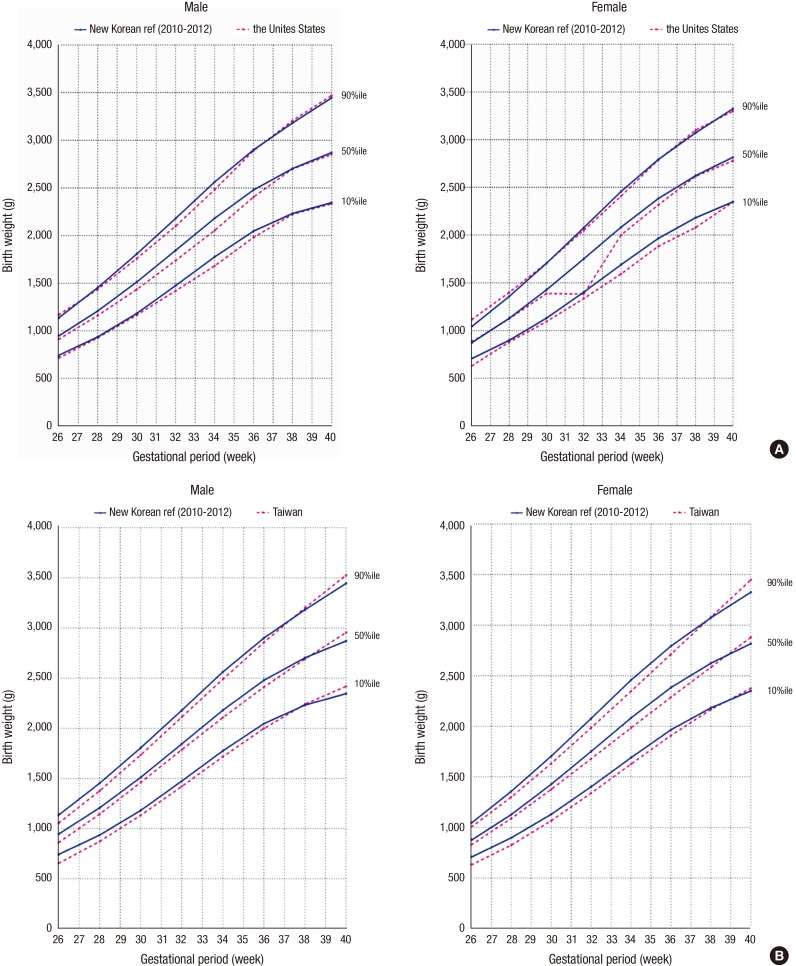

Graphs of data from 7,993,166 singleton-birth infants born in Brazil between 2003 and 2005 were compared with the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile graphs; both boys and girls were heavier than singleton-birth infants in Brazil in the 10th percentile but lighter in the 90th percentile (Fig. 6) (15). Compared with data of 676,605 singleton births in Canada between 1994 and 1996 (16), Canadian infants were lighter or similar in BW until 36 weeks' gestation, but BW of Korean infants were much lower than those of Canadian infants after 36 weeks' gestation (Fig. 7). While BW of twins were higher than those of American and Taiwanese boys and girls, the gap decreased after 38 weeks' gestation (Fig. 8) (17,18). In the American study, the fetal growth of each twin was estimated from regression curves fit to ultrasonographic fetal weight measurements, and the estimated data could have a bias.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of singleton birth weight percentile curves of Brazil. %ile, percentile.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of singleton birth weight percentile curves of Canada. %ile, percentile.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of twin birth weight percentile curves of the United States (A) and Taiwan (B). %ile, percentile.

DISCUSSION

The most basic characteristic of babyhood is growth, and since abnormal growth may be a critical signal of disease, its evaluation is essential (19). Growth begins in the uterus, and BW, the starting point after birth, is an important index for quantifying uterine and later growth and related to complications including perinatal mortality and perinatal distress (20). BW is also related to the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adulthood (21). However, since infant BW is affected by both environmental and genetic factors, it is important to identify the percentile distribution of BW during pregnancy using recent data to evaluate infants (22). In fact, the reference BW of the 90th percentile, which was the reference for 30 weeks' gestation singleton births in the present study, was 1,924 g for boys and 1,837 g for girls. These weights were higher than those reported in Korea approximately 10 years previously (boys, 1,855 g; girls, 1,758 g). In addition, the reference BW were higher than those reported in the United States for 257,855 singleton births between 1998 and 2006 (boys, 1,761 g; girls, 1,693 g), and in Canada for 676,605 singleton births between 1994 and 1996 (boys, 1,837 g; girls 1,783 g). The reference BW for the 10th percentile at 40 weeks' gestation were 3,000 g for boys and 2,890 g for girls. These weights were higher than those in Korea 10 years previously (boys, 2,898 g; girls, 2,790 g) and those reported in the US (boys, 2,950 g; girls, 2,855 g) but were lower than those in a Canadian report (boys, 3,079 g; girls, 2,955 g) (6,16,23).

In this study, male singleton and multiple infants had higher BW than female infants at each GA. These findings are consistent with those of other studies. According to the report by Kramer et al. (16), the mean BW of male singletons is approximately 50 g heavier than that of female singletons at the 90th percentile at 30 weeks' gestation, increasing to 120 g heavier at the 10th percentile at 42 weeks' gestation. Roberts et al reported that the mean BW of male twins is approximately 100 g heavier than that of female twins at 27–29 weeks' gestation, increasing to 150 g heavier at 40 weeks' GA (24). Fetal growth is generally influenced by placental properties and the fetus's inherent growth potential. This observed gender-specific difference may be caused by gender-dependent differences in “sensitivity” to the placental and fetal tissue to fasting plasma glucose or weight gain–associated factors (25). The differences in BW between males and females reportedly differed less in multiples than in singletons (26). However, our study showed that this gender difference was almost the same within singleton and multiple births.

Compared to singleton-birth infants, multiple-birth infants have limited growth within the uterus; therefore, the evaluation criteria for infant BW need to be changed depending on singleton or multiple births (17). The growth of twins and triplets is reportedly similar to that of singleton-birth infants until 32 and 29 weeks' gestation, respectively, after which point it differs from that of singleton-birth infants. In contrast, it has been reported that a difference in growth between singleton- and multiple-birth infants began to appear after 28 weeks since multiple-birth infants showed growth limitations after 28 weeks' gestation (23,27). According to the report by Bleker et al. (26), the difference in BW between singletons twins at 39–40 weeks' gestation was 600 g. Our study showed a similar difference in BW between singletons and multiples until about 30 weeks' gestation, but as GA increased after 30 weeks, the difference was greater. As such, the mean BW of male singletons is approximately 460 g heavier than that of female singletons, while that of male multiples is 410 g heavier than that of female multiples at the 50th percentile at 40 weeks' gestation.

We compared our new curve with previously published data on singleton (both sexes) and twin BW percentiles by GA in 2000–2004 in Korea. When the validation samples were categorized as small for GA (SGA; < 10th percentile of a standard BW curve for GA)/appropriate for GA (10th percentile ≤ appropriate for GA ≤ 90th percentile of a standard BW curve for GA)/large for GA (> 90th percentile of a standard BW curve for GA), the new curves had lower average weights at younger GA until 30–31 weeks and higher or similar average weights after 31 weeks on the SGA curve. The differences found between our new curves and previous curves may be explained in part by differences in the infants who were born in 2010–2012 versus those born in 2000–2004. These differences in BW distribution may be explained by multiple factors that influence BW in developed countries, such as smoking, low weight gain during pregnancy, low pre-pregnancy body mass index or demographic changes by increasing numbers of multicultural families in Korea (28,29). On the contrary, the new curves had higher average weights at younger GA until 32–33 weeks and lower average weights after 33 weeks on the large for GA curve. Data from Statistics Korea reported that the percentages of HBW infants among total live births decreased over the years as follows: 6.7% (1993), 6.3% (1995), 5.1% (1997), 4.5% (2000), and 3.5% (2010). Between 1993 and 2010, the average BW of Korea was reduced from 3.31 kg in 1993 to 3.22 kg in 2010 by approximately 0.1 kg (30). Recent changes in percentages of HBW infants and average BW could help to explain why the new curves are shifted down in the older GA on the appropriate GA and large for GA curves. Compared with twin curves, our twin curve had similar average weights at < 37 weeks but higher weights at > 37 weeks. The reason for these differences is currently unknown and should be confirmed in further studies that include fetal outcome.

Despite the fact that the total number of newborns in 2010 was lower than that in 2000, the number of multiple gestations increased from 10,723 in 2000 to 12,841 in 2010, while the multiple birth rate increased 1.6 times from 16.9 in 2000 to 27.3 in 2010 as results of the ovulation inducing agent related to artificial insemination and the increased use of in vitro fertilization (31,32,33). Although multiples compared with singletons have higher mortality and morbidity rates, few studies have examined the BW of multiples in Korea (34,35). In this study, we tried to establish the distribution of BW percentiles considering newborn plurality. However, the overall data of newborns by the Korean Statistical Information (2010–2012) have estimated errors at 28–32 weeks' gestation. The distribution curves represent the double humped curve. The estimated error data were located on the right, which means heavier newborns for GA. This is the limitation of the large data analysis, but this report removed errors using the Finite Gaussian mixture model.

In this study, we established the new reference range of the neonatal BW percentiles considering GA, sex, and plurality of newborns in Korea. We expect the updated data to be utilized as a new Korean reference to improve clinical growth assessments in newborns.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study conception and design: Lee JK, Jang HL, Kang BH, Shim KS, Choi YS, Bae CW, Chung SH. Data acquisition: Lee KS. Statistical analysis: Lim JW. First draft of the manuscript: Lee JK, Chung SH. Manuscript approval: all authors.

References

- 1.Babson SG, Behrman RE, Lessel R. Fetal growth. Liveborn birth weights for gestational age of white middle class infants. Pediatrics. 1970;45:937–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas P, Peabody J, Turnier V, Clark RH. A new look at intrauterine growth and the impact of race, altitude, and gender. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E21. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ananth CV, Wen SW. Trends in fetal growth among singleton gestations in the United States and Canada, 1985 through 1998. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26:260–267. doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.34772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JJ, Kim MH, Ko KO, Kim KA, Kim SM, Kim ER, Kim CS, Son DW, Shim JW. The study of growth measurements at different gestatioal ages of Korean newborn the survey and statistics. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2006;13:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JJ, Park CG, Lee KS. Birth weight distribution by gestational age in Korean population: using finite mixture model. Korean J Pediatr. 2005;48:1179–1186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JJ. Birth weight for gestational age patterns by sex, plurality, and parity in Korean population. Korean J Pediatr. 2007;50:732–739. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim JS, Lim SW, Ahn JH, Song BS, Shim KS, Hwang IT. New Korean reference for birth weight by gestational age and sex: data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (2008-2012) Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;19:146–153. doi: 10.6065/apem.2014.19.3.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in neonatal epidemiology during the last 3 decades in Korea. Neonatal Med. 2013;20:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Korea. Infant, Maternal and Perinatal mortality Statistics 2010~2012. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2012. Cause of death statistics, maternal death rate; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Family Database [Internet] 2012. [accessed on 1 October 2015]. Available at http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FAMILY.

- 11.Platt RW, Abrahamowicz M, Kramer MS, Joseph KS, Mery L, Blondel B, Bréart G, Wen SW. Detecting and eliminating erroneous gestational ages: a normal mixture model. Stat Med. 2001;20:3491–3503. doi: 10.1002/sim.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oja H, Koiranen M, Rantakallio P. Fitting mixture models to birth weight data: a case study. Biometrics. 1991;47:883–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1992;11:1305–1319. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flegal KM. Curve smoothing and transformations in the development of growth curves. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:163S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.1.163s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedreira CE, Pinto FA, Pereira SP, Costa ES. Birth weight patterns by gestational age in Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2011;83:619–625. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652011005000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS, Allen A, Abrahamowicz M, Blondel B, Bréart G, Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min SJ, Luke B, Gillespie B, Min L, Newman RB, Mauldin JG, Witter FR, Salman FA, O'sullivan MJ. Birth weight references for twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1250–1257. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.104923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu IJ, Hsieh CJ, Jeng SF, Wu HC, Chen CY, Chou HC, Tsao PN, Lin SJ, Chen PC, Hsieh WS. Nationwide twin birth weight percentiles by gestational age in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KH. Growth assessment and diagnosis of growth disorders in childhood. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2003;46:1171–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AC, Mullany LC, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Adhikari RK, Shrestha SR, Darmstadt GL. Risk factors for neonatal mortality due to birth asphyxia in southern Nepal: a prospective, community-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1381–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osmond C, Barker DJ. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):545–553. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein H. Factors related to birth weight and perinatal mortality. Br Med Bull. 1981;37:259–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e214–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts CL, Lancaster PA. National birthweight percentiles by gestational age for twins born in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35:278–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voldner N, Frøslie KF, Godang K, Bollerslev J, Henriksen T. Determinants of birth weight in boys and girls. Hum Ontogenet. 2009;3:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleker OP, Breur W, Huidekoper BL. A study of birth weight, placental weight and mortality of twins as compared to singletons. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb10577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garite TJ, Clark RH, Elliott JP, Thorp JA. Twins and triplets: the effect of plurality and growth on neonatal outcome compared with singleton infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer MS. Socioeconomic determinants of intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52(Suppl 1):S29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Hahn MH, Chung SH, Choi YS, Chang JY, Bae CW, Kim YK, Kim HR. Statistic observation of marriages, births, and children in multi-cultural families and policy perspectives in Korea. Korean J Perinatol. 2012;23:76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang BH, Moon JY, Chung SH, Choi YS, Lee KS, Chang JY, Bae CW. Birth statistics of high birth weight infants (macrosomia) in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2012;55:280–285. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2012.55.8.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim JW. The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:429–435. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.11.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blickstein I. Normal and abnormal growth of multiples. Semin Neonatol. 2002;7:177–185. doi: 10.1053/siny.2002.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozturk O, Templeton A. In-vitro fertilisation and risk of multiple pregnancy. Lancet. 2002;359:232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imaizumi Y. A comparative study of zygotic twinning and triplet rates in eight countries, 1972-1999. J Biosoc Sci. 2003;35:287–302. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003002876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ananth CV, Chauhan SP. Epidemiology of twinning in developed countries. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36:156–161. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]