Abstract

The endothelial cells lining the brain capillaries separate the blood from the brain parenchyma. The endothelial monolayer of the brain capillaries serves both as a crucial interface for exchange of nutrients, gases, and metabolites between blood and brain, and as a barrier for neurotoxic components of plasma and xenobiotics. This “blood-brain barrier” function is a major hindrance for drug uptake into the brain parenchyma. Cell culture models, based on either primary cells or immortalized brain endothelial cell lines, have been developed, in order to facilitate in vitro studies of drug transport to the brain and studies of endothelial cell biology and pathophysiology. In this review, we aim to give an overview of established in vitro blood–brain barrier models with a focus on their validation regarding a set of well-established blood–brain barrier characteristics. As an ideal cell culture model of the blood–brain barrier is yet to be developed, we also aim to give an overview of the advantages and drawbacks of the different models described.

Keywords: Blood–brain barrier, endothelium, astrocytes, pericytes, stem cells

Introduction

The blood–brain barrier

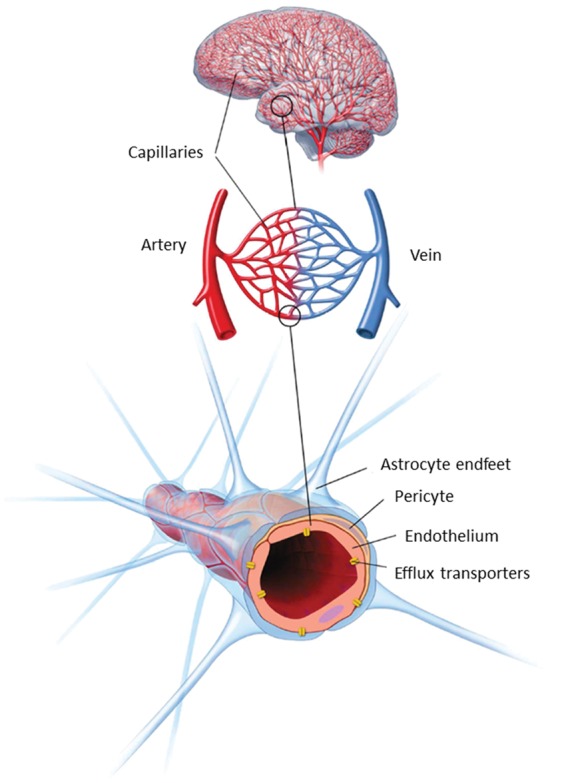

The small capillaries of the brain constitute unique morphological and functional units that serve a number of different roles. The capillaries have to supply the nervous tissue with nutrients and oxygen, they have to participate in the maintenance of water and electrolyte balance in the brain interstitial fluid and they must protect the neurons from potentially harmful substances present in the blood. The barrier function of brain capillaries, the blood–brain barrier (BBB), is primarily due to the presence of complex tight junctions and to a specific expression pattern of different solute carriers (SLCs) and ABC-type efflux transporters. The capillaries of the brain are complex structures, consisting of several cell types (see Figure 1). The endothelial cells constitute the capillary wall and thus the actual barrier, but the endothelial cells are surrounded by pericytes (coverage estimated to be ∼30%).1 The endothelial cells and pericytes are surrounded by a basement membrane, and astrocyte endfeet ensheath the abluminal side of the capillaries with a coverage estimated at 99%.1

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the structure of the neurovascular unit. The endothelial cells of the brain capillaries are covered (∼30%) with pericytes, embedded in the basement membrane of both endothelial cells and astrocytes. The endothelium and attached pericytes are covered almost completely by a surrounding layer of astrocyte endfeet. Communication between the cell types of the neurovascular unit ensures that the brain endothelium maintains the blood–brain barrier specific phenotype. Modified from Lægemiddelforskning 2015 (http://www.farma.ku.dk/index.php/Laegemiddelforskning-2015/11840/0/).

Both pericytes and astrocytes regulate the phenotype of the endothelium, through mechanisms not yet fully understood but involving cell–cell communication via soluble factors and possibly also direct contact interactions.2,3 The brain capillary endothelial cells (BCEC) and the surrounding accompanying cell types thus constitute the “ neurovascular unit” (NVU), a term reflecting the specialized and unique cellular structure of the brain microvasculature.

There is great interest in generating in vitro models reflecting the properties of the BBB. An ideal in vitro model of the BBB would allow mechanistic studies of BBB tight junctions, transporters, enzymes, macromolecular and immune cell trafficking and signaling and be suitable for rapid screening of BBB permeability for new central nervous system (CNS) drug candidates.

Validation markers for in vitro BBB models

A set of validation markers was chosen to compare the different in vitro models in this review. The markers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Blood–brain barrier validation markers.

| Category | Property | Relevance | Validation | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation of cell lineage | Monolayer of thin cells with large surface area | All studies | Visualization, F-actin staining | 4,5 |

| Expression of endothelial markers | Von Willebrand’s Factor/PECAM-1 | 6–8 | ||

| Tight junctions | Occludin claudin-5 ZO-1 | Studies of tight junctions – transendothelial transport and uptake studies – Cell polarization | mRNA and protein expression – localization | 9–11 |

| High junctional tightness | TEER and permeability measurements | 12–16 | ||

| Efflux transporters | P-pg | Transendothelial transport and uptake studies – drug delivery to/through the BBB – toxicity | mRNA and protein expression – Cellular uptake or efflux in absence/presence of inhibitors – bi-directional transport studies | 17,18 |

| BCRP | 19–22 | |||

| Mrp | 23–25 | |||

| SLC expression | Glut-1 | Transendothelial transport and uptake studies – drug delivery to/through the BBB. Brain nutrition studies | mRNA and protein expression – Cellular uptake in absence/presence of inhibitors – transendothelial transport studies | 26–28 |

| LAT-1 | 29,30 | |||

| MCT-1 | 31–33 | |||

| Receptor systems | Transferrin receptor | Studies of receptor-mediated transport, brain nutrition studies | mRNA and protein expression – transferrin uptake – transendothelial transport of iron | 34–36 |

| Responsiveness to regulation from NVU cells | Induction by astrocytes | Studies of cell regulation and NVU signalling | Regulation of TEER, P-gp expression and cell morphology | 37–40 |

| Induction by pericytes | Regulation of TEER, proteins involved in vesicular transport | 41,42 |

The markers shown in Table 1 are not a complete set of BBB characteristics. An important issue is that knowledge about the in vivo BBB is still lacking, which makes it difficult to firmly establish the features that an ideal BBB model should possess. Recent studies focusing on the BBB transcriptome and proteome are beginning to accumulate knowledge, which in time may provide a more complete fingerprint of the BBB for the models to mimic.43–51 While no model exactly mimics the in vivo BBB expression of enzymes, transporters, receptors, and structural proteins, they can nevertheless be useful tools. The validation markers chosen in this study have all been shown to have functional importance at the BBB, which makes their expression and function in the model important, at least for studies concerning subjects related to this characteristic.

An important feature of BBB models is high junctional tightness. This is often measured as transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER). TEER obtained by separate groups in separate studies may differ somewhat, not only because of differences in actual junctional tightness but also because of differences in measuring equipment (chopstick electrodes, cup electrodes, impedance measurements), temperature, and handling of the cells during measurements.52 TEER may also be difficult to translate to a functional estimate of tightness, as the tightness of the endothelial monolayer depends both on the composition of the tight junction complexes and on the size of the compound of interest. Validation of functional tightness can also be performed by permeability studies with hydrophilic tracer molecules such as Lucifer yellow (444 Da), sodium fluorescein (376 Da), sucrose (342 Da), or mannitol (180 Da). TEER correlates with permeability for a given small hydrophilic molecule,53–58 but the correlation depends strongly on the size of the molecule and the experimental design (shaking/no shaking, change of medium, sampling during the experiment, single point estimation/steady state calculations). Thus, the optimal characterization of paracellular permeability should include both TEER and tracer flux. Expression and junctional localization of specific tight junction proteins are related characteristics. Tight junctions exist in a range of different tissues and the specific combination, especially of claudins, gives the junctional complex its specific properties.59,60 Claudin-5 has been established as a tightening claudin with high BBB expression, and loss of claudin-5 causes BBB leakage of small molecules.9 Thus, claudin-5 expression is essential in a BBB model if it is to be used for studying transport- or tight junction-related phenomena.

Efflux transporters of the ABC family and SLCs play essential roles in the BBB permeability of small molecules, both endogenous compounds and xenobiotics.2 This makes their expression, correct localisation, and functionality important validation characteristics for a BBB model, at least if the model is to be used for BBB permeability screening, CNS-toxicity studies, pro-drug formulation studies, or studies of nutritional status of the BBB. Validation can be performed via protein or mRNA expression studies, but functional validation with accumulation or bi-directional transport of model substrates and inhibitors should be performed if the model is to be applied in studies where transporters may have a direct influence on the outcome. Macromolecule transport across the BBB is more controversial. Several receptor systems potentially able to mediate transcytosis and thus CNS delivery of ligands or compounds conjugated to ligands have been investigated including insulin receptor, LRP-1, LDL-receptor, leptin receptor, glutathione receptor, diphtheria toxin receptor, and transferrin receptor61–68 (for review of receptor systems applied for brain targeting, see literature69). Of these, the most studied receptor system shown to facilitate CNS delivery of clinically relevant doses in vivo is the transferrin receptor.35,70 LRP-1 has also been utilized to deliver therapeutics across the BBB, for instance by conjugating paclitaxel to the LRP-1 substrate, angiopep-2, which caused a significant increase in the brain uptake and survival of tumor implanted mice.71,72 Similar results have been demonstrated with angiopep-2 coupled to monoclonal antibodies or doxorubicin.73,74 However, controversies exist regarding LRP-1 expression in brain endothelial cells, where some studies have shown that it is mainly found in pericytes,51,75,76 whereas others show expression in endothelial cells.77–79 The transferrin receptor is widely agreed to be highly expressed in brain endothelial cells in vivo, which makes the transferrin receptor a good validation target when setting up a new model.

A brief history of in vitro BBB model development

Efforts to generate cell cultures of BCEC started in the early 1970s with isolations of brain capillaries.80,81 A combination of mechanical homogenization of brain tissue and sucrose gradient centrifugations yielded pure and intact brain capillaries, which could be used directly to study BBB properties.81 The isolation techniques have since been modified with the use of filtration steps instead of, or in combination with, centrifugation, and isolated capillaries have been used in a number of functional assays to quantify P-glycoprotein (P-gp) activity and tight junction integrity as well as studying transporter regulation and other properties.24,79,82–84 The methods for isolating brain capillaries were further developed to yield isolation of primary endothelial cells.4,85–87 Isolated brain capillaries were treated with a mixture of enzymes to degrade the basement membranes, remove the pericytes, and release the endothelial cells. These cultures were based solely on endothelial cells without induction by other cells of the neurovascular unit (see Figure 2).

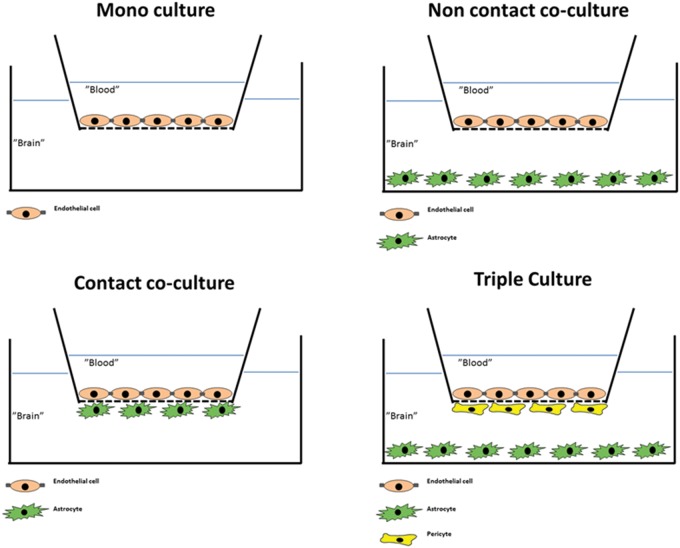

Figure 2.

Commonly used configurations used for culture of brain endothelial cells. Mono-culture: Brain endothelial cells are grown on the upper surface of permeable supports in a two-compartment cell culture system. Media may be added astrocyte-conditioned medium to promote growth and differentiation in the absence of the other cell types of the neurovascular unit. Non-contact co-culture: The endothelial cells are seeded on the upper surface of the support, while astrocytes (or other cell types, often pericytes) are seeded at the bottom of the culture well. This configuration allows for induction of the endothelium by diffusible factors from the “feeder cells” at the bottom of the well, while the insert can be removed after culture for experiments, which can be performed on endothelial cells only. Contact co-culture: Astrocytes (or other cell types) are seeded on the lower surface of the support with endothelial cells on the upper surface. This may allow for direct contact between the opposing cell types. A drawback of the configuration is that the two cell types cannot readily be separated in experimental protocols employing Western blotting or transport and accumulation studies. Triple culture: This configuration includes in its most common form endothelial cells seeded on the upper surface of the support, pericytes seeded on the lower surface, and astrocytes seeded on the bottom of the culture wells. This configuration mimicks the cell arrangement at the neurovascular unit, and allows for interactions between all three cell types. However, due to the different cell types involved, this configuration is also more demanding in terms of workload and experimental skills.

Debault and Cancilla87 reported that co-culture of isolated endothelial cells with C6 glioma cells induced γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity in the endothelium, which was otherwise lost in culture. Furthermore, Tao et al.88 prepared co-cultures of endothelial cells on coverslips in proximity to an astrocyte cell layer and showed an increase in tight junction length and complexity by freeze fracture studies. Dehouck et al.89 used a co-culture approach in studies with bovine endothelial cells and rat astrocytes seeded on opposite surfaces of permeable membranes in transwell culture inserts (contact-co-culture) (see Figure 2). This caused a tightening of the cell junctions as reflected by an increase in TEER to approximately 660 Ω cm2 as well as better retention of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. The ability of astrocytes to increase TEER in endothelial cell cultures has been demonstrated in numerous later studies, both with contact and non-contact co-cultures (astrocytes seeded on the bottom of the plate below the filter insert) and with mono-cultures of endothelial cells cultured in astrocyte-conditioned medium.5,90–96 More recently, pericytes have been included in some BBB models either as a replacement for astrocytes or in triple culture with astrocytes and endothelial cells.97–103 The endothelial cell/pericyte/astrocyte triple cultures have shown slightly higher TEER values than corresponding endothelial cell/astrocyte co-cultures in studies on rat primary cells, but the exact mechanisms of junctional regulation remain to be established.

The years of model development have resulted in a range of well-established and characterized models run on a routine basis in different laboratories. These are based on pig,104–106 bovine,89,90,107 rat,96,98 and mouse endothelial cells.108–110 These models of non-human origin have provided a wealth of information on the physiology and pathophysiology of the BBB and have allowed very valuable cross-validation between models. Human tissue is difficult to obtain on a regular basis, which has limited the development of primary cultures of human brain endothelial cells and cell-based human models.111–113 However, two different methodological approaches to circumvent this problem have been established. Different groups established and characterized immortalized human brain endothelial cells114,115 and three different groups have published BBB models based on stem cell-derived endothelial cells.116–118

Aim of the review

Many of the models generated during the past 40 years continue to be used in different research groups to analyze several aspects of BBB biology and drug targeting. However, none of the models applied behave in exactly similar ways, and small differences in the way the individual laboratories handle the models can make it a challenge to obtain a clear overview of the benefits and drawbacks of the various in vitro BBB-models.

The aim of this review is to give an updated overview of in vitro models of the BBB, to aid in navigating and interpreting the literature, and in choosing the most practical and appropriate models for particular projects. We have selected a number of commonly used – as well as newly developed models derived from mouse, rat, bovine, porcine, and human endothelial cells, and assessed these against a pre-defined set of BBB validation markers including endothelial phenotype, marker protein expression profile, and function. This may provide a clearer overview of the strengths and weaknesses of commonly applied models and point towards questions still unanswered.

Mouse models – Immortalized and primary mouse brain endothelial cultures

Primary cultures of mouse brain endothelial cells must be freshly isolated prior to experiments and show variation from batch to batch. Coisne et al.109 reported a primary cell co-culture model with mouse endothelial cells and astrocytes, which presented classic BBB characteristics, such as occludin, claudin-3, claudin-5, and P-gp expression. The model had high junctional tightness with TEER averaging almost 800 Ω cm2 and sucrose permeability of 4.5 × 10−6 cm/s (see Table 2). However, TEER measurements of this magnitude are rarely reported in studies on mouse primary endothelial cells, and TEER values of 100–300 Ω cm2 are more commonly reported.42,119–121 Thus, considerable effort has been invested in the generation of immortalized mouse brain endothelial cell lines, which have the advantage of being stable for a number of passages and may yield a large number of endothelial cells with the same genetic and phenotypical characteristics. Furthermore, the established protocols for cell isolation and immortalization can be used to generate BCEC cell lines from genetically modified animals. Work by the Risau group122 resulted in the first mouse brain endothelial cell lines generated by immortalization with Polyoma middle T antigen. bEND.5 and bEND.3 are commercially available cell lines based on this immortalization strategy; however, both cell lines generally display low TEER (around 50 Ω cm2).123–125 Forster et al.108,110,126 generated the alternative cell lines, cEND and cerebEND, from mouse cerebral and cerebellar capillaries, respectively (see Table 2). Both cell lines form monolayers and show spindle-shaped morphology.110,126 The cEND cell line has TEER varying from 300 to 800 Ω cm2 and strong occludin and claudin-5 expression at the tight junctions. The higher electrical resistance of the cEND cell line corresponded to lower permeability of FITC-Dextran 4, 10, 70, and 500 kDa,110 as compared to bEND.3, but functional tightness has not been characterized using small molecule tracers. Both cell lines, cEND and cerebEND, express endothelial cell markers and junctional proteins (Pecam-1, VE-cadherin, claudin-5, occludin, ZO-1) as shown at the mRNA and protein level.110,127 Low levels of claudin-1, claudin-3, and claudin-12 were detected at the mRNA and protein levels in cEND and cerebEND.126,128–130

Table 2.

Mouse in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Morphology, tightness and astrocyte/pericyte induction.

| Model type | Endothelial morphology | Junction Claudins | ∼TEER (Ohm·cm2) (mean values) | Permeability 10−6 (cm/s) | Occludin/ZO proteins | Astrocyte induction | Pericyte induction | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary mouse BCEC/astrocyte coculture | Monolayer Spindle shape | 3 and 5 (ICC) | 800 | 4.5 (sucrose) | Occludin (ICC) | – | – | 109 |

| cEND (immortalized mouse cerebral endothelial cells) | Monolayer Spindle shape (serum) Cobblestone (hydrocortisone + insulin) | 5 (ICC,WB), 3 and 12 (WB) low levels of 1 (mRNA) | 300 (serum) to 800 (Hydrocortisone + insulin) | – | Occludin (ICC, WB) | – | – | 110,126,129 |

| cereBEND (immortalized mouse cerebral endothelial cells) | Monolayer Spindle shape | 5 (ICC,WB) low levels of 1,3,12 (mRNA) | 500 | – | Occludin (ICC, WB) ZO1 (ICC, WB) | Slight increase in TEER by coculture with rat glioma C6 cell line | – | 126,130,131 |

: not investigated; ICC: Immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

cEND cells respond strongly to glucocorticoids by induction of BBB properties. Glucocorticoids induce cytoskeletal rearrangements, regulate tight junction proteins occludin and claudin-5, and cause TEER to increase up to 1000 Ω cm2.110,132–134

The cerebEND model has been further developed and co-cultured with an immortalized rat glial cell line (C6), which caused a slight increase in TEER.130 The presence of P-gp, breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and multidrug-resistance protein-4 (Mrp-4) has been demonstrated in cerebEND cells by Western blot and immunofluorescence, but has not been shown in the cEND cell line130 (see Table 3). Functional tests in uptake assays with specific substrates for P-gp (calcein-AM), Mrp-4 (fluo-cAMP), and BCRP (Bodipy-FL-prazosin) showed changes in transporter activity due to oxygen/glucose deprivation (OGD) and due to co-culture of cerebEND cells with C6 astrocytoma.130 Expression of glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1) has been demonstrated in cEND and cerebEND at the mRNA and protein level.126,131

Table 3.

Mouse in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Receptor and transporter expression and function.

| Model type | ABC transporter expression/function | Vectorial net transport of ABC substrates | TFR expression/ function | LAT-1 expression/ function | Glut-1 expression/ function | MCT-1 expression/ function | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary mouse BCEC/astrocyte coculture | P-gp expression (WB) | – | – | – | – | – | 109 |

| cEND (immortalized mouse cerebral endothelial cells) | – | – | – | – | WB | – | 110 |

| cereBEND (Immortalized mouse cerebral endothelial cells) | P-gp, BCRP and Mrp-4 expression (ICC, mRNA, WB) | – | – | – | mRNA, WB (low base levels, upreg. by OGD) | – | 126,130,131 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

Both the cEND and the cerebEND cell lines respond to inflammatory stimuli. Treatment of the cEND and cerebEND cells with TNFα resulted in decreased tight junction protein expression and lower TEER.126,133 TNFα induced the expression of inflammatory stress markers including VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in both cEND and cerebEND.126 Moreover, cEND treated with serum from multiple sclerosis patients showed decrease in occludin, claudin-5, and VE-cadherin levels135 and increased secretion of cytokines and growth factors, such as Ccl12 and Csf3.136

In summary, both in vitro models cEND and cerebEND have proved useful tools in studies of regulation of BBB protein expression under normal and pathophysiological conditions. Both models still need to be characterized regarding the expression and activity of SLC-transporters such as large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT-1) and mono carboxylic acid transporter-1 (MCT-1). Moreover, the effects of co-culture with pericytes on barrier tightness, TJ expression, transporter expression, and general endothelial phenotypic traits need to be further investigated.

Rat models – Mono-, co- and triple cultures of rat BCEC

Rat brains were the first source of BCEC for development of BBB models.85 Contaminating pericytes presented a major problem for primary rat BCEC cultures, and different methods have been employed to increase the purity of the endothelial cultures.137,138 Selection with the P-gp substrate, puromycin, proved successful139 and is now included in the culture protocol in a number of laboratories.55,93,140,141 Puromycin is typically present during the first two to three days of culture. This leads to tighter in vitro models,139,140 which may be caused by a more coherent endothelial monolayer due to the absence of pericytes. Alternatively, the higher resistance may be due to a selection of capillary endothelial cells over endothelial cells from larger microvessels.142 Rat models have been applied in different versions: mono-cultures of endothelial cells have been widely applied, but most recent studies use co-cultures- either endothelial/astrocyte co-cultures or endothelial/astrocyte/pericyte triple cultures. Both purified type-1 astrocytes97 and primary mixed glial cultures96,139 have proven efficient in the induction of a BBB phenotype in rat primary endothelial co-cultures, and models based on astrocyte co-cultures typically present well-characterized BBB models (see below).55,93,141 The triple cultures including pericytes were developed to further mimic the neurovascular unit.97,98 Initially, it was shown that inclusion of pericytes caused a greater differentiation of the brain endothelial cells than astrocyte or pericyte co-culture alone,98 and since then the model has been applied in 13 published papers regarding oxidative stress,143,144 amyloid-ß toxicity,145 and permeability screening146–148 amongst others.

Rat models generally display low to medium TEER, often around 100–300 Ω cm2 depending on the culture method (mono-culture, astrocyte/pericyte co/triple culture, induction with cAMP and/or glucocorticoids).58,96,97,140,141,147–154 However, several studies also report that rat models can reach TEER around 500–800 Ω cm2 under optimal culture conditions.55,93,97,145,155 This translates into permeabilities of sodium fluorescein, Lucifer yellow, and sucrose around 2–19 × 10−6 cm/s in the models displaying lower TEER,96,97,140,141,147,150,156 whereas permeabilities in the range of 0.8–3 × 10−6 cm/s have been reported in the high TEER models55,145,155 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Rat in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Morphology, tightness and astrocyte/pericyte induction.

| Model type | Endothelial morphology | Junction Claudins | ∼TEER (Ohm · cm2) (mean values) | Permeability 10−6 (cm/s) | Occludin/ZO proteins | Astrocyte induction | Pericyte induction | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary rat BCEC/astrocyte co-culture | Monolayer Spindle shape | 5 (ICC,WB) low levels of 12 (mRNA) | 300–600 (Hydrocortisone) | 1.4 (Sucrose) 4.3(Lucifer yellow) | Occludin (ICC, WB) ZO1 (ICC, WB) | Increase in TEER, lowering of Pflourescein | – | 93,96,98, 141,157 |

| Primary rat BCEC/astrocyte/ pericyte triple cultures | Monolayer Spindle shape | 5 (ICC,WB) | 350–723 | 2–4 (flourescein) | Occludin (ICC, WB) ZO1 (ICC, WB) | Increase in TEER, lowering of Pflourescein | Increase in TEER | 97,98, 145,155 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

Astrocyte(+); mixed glial culture dominated by astrocytes.

These high TEER-low permeability models have only been achieved using the co- and triple cultures.55,93,97,145,155

The rat models have been shown to express tight junction proteins claudin-5, occludin and ZO-1 in mono-cultures,140,150 astrocyte co-cultures,55,141,151 and triple cultures,97,155 where claudin-5 and ZO-1 protein expression levels are increased relative to mono-cultures.97 Also claudin-1, -3 and -12, and ZO-2 have been shown at either mRNA or protein level.96,157

Data on the rat BBB transcriptome45 and ABC transporters at the rat BBB158 have been obtained on isolated rat brain microvessels and isolated BCEC. Several BBB proteins were found to be down-regulated in mono-culture, notably Glut-1 (39 fold), P-gp (MDR-1A) (14 fold), and transferrin receptor (9 fold).159 Similar down-regulation has been observed in an endothelial/astrocyte co-culture model, where P-gp, transferrin receptor, Mrp-4, and Glut-1 expression levels were largely reduced upon six days of co-culture, whereas expression of BCRP, Mrp-1, and insulin receptor was retained.58 Although down-regulated, expression of a range of ABC transporters including P-gp, BCRP, and at least one isoform of Mrp is still evident at the mRNA level, protein level or both, in rat models using mono-cultures,160 astrocyte-co-cultures,58,96 and triple cultures.97,153 Functional P-gp expression has been well characterized in both astrocyte co-culture models and the triple-culture models.55,93,96,97,141,151 Bi-directional transport studies with rhodamine123 demonstrate vectorial transport favoring the brain-to-blood direction with an efflux ratio of approximately 2.5 in the triple-culture model,97 whereas similar studies in the astrocyte co-culture models have shown efflux ratios around 1.7 for rhodamine 123141 and 6.1 for amprenavir.58 Functional P-gp expression is further demonstrated by apical uptake studies with P-gp substrates showing increased uptake when P-gp inhibitors were co-administered55,96,141,153,156,160 (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Rat in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Receptor and transporter expression and function.

| Model type | ABC transporter expression/function | Vectorial net transport of ABC substrates | TFR expression/ function | LAT-1 expression/ function | Glut-1 expression/ function | MCT-1 expression/ function | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary rat BCEC/astrocyte co-culture | -P-gp (ICC, WB) BCRP, Mrp-3, Mrp-4, Mrp-5 (mRNA) Inhibitor data on uptake for all. | ER of 1.8 for Rhod 123 ER of 6.1 for Amprenavir (inhibited by GF120918) ER of 7.7 for Dantrolene (inhibited by Ko143) | ICC, mRNA, Tf-Cy3 binding | – | mRNA | – | 58,93,96,141, 157,165 |

| Primary rat BCEC/Astrocyte/ Pericyte triple co-culture | P-gp, Mrp-1 (ICC,WB). Inhibitor data on Rhod 123 uptake | ER of 2.5 for Rhod 123 | – | – | ICC, WB | – | 97,98,145 |

: not investigated; ICC: Immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

The functionality of BCRP on primary rat brain endothelial cells has been shown in the astrocyte co-culture model, both by accumulation assays96 and by bi-directional transport assays,58 in both cases by co-application of the BCRP inhibitor, Ko143.

The expression of glucose and amino acid transporters was demonstrated in primary cultures of brain endothelial cells,97,159,161–163 but few rat BBB culture models have been characterized for SLC transporter functionality. Active glucose uptake was described in primary rat brain endothelial cells, which was positively modulated by n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.162,163 Functional amino acid uptake was also studied in rat primary models.161,164

There could be several reasons for the scarcity of functional studies on SLC transporters in BBB models. Influx transporters, such as Glut-1, are more sensitive to down-regulation by serum-free monolayer culture conditions than efflux pumps.159 Garberg et al.166 suggested that the in vitro BBB models tested were not tight enough to allow estimation of the transcellular component of small molecule transport of glucose and amino acids in permeability assay settings. It remains to be seen whether the newly described and tighter BBB models will be better applicable in uptake and especially in permeability assays for influx transport studies.

An alternative triple-culture model including neurons instead of pericytes has been developed. This showed increased γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity and slightly increased junctional tightness as compared to an astrocyte-endothelial co-culture model.154 The average TEER of the triple culture was 250–300 Ω cm2, which is still below the TEER reported in the tightest rat models.154

A major advantage of the rat BBB models described above is that syngeneic co-cultures can be established and results obtained on rat BCECs can be correlated with in vivo data in the same species and even strain of rats. The genome and transcriptome of rats are well studied, and a large set of antibodies are available for rat antigens. The development of a complex BBB model, like the triple culture is time-consuming and needs expertise, therefore a patented frozen ready-to-use kit version of the rat endothelial/pericyte/astrocyte model was developed and successfully used in different BBB studies.144,147–149

Bovine models – Astrocyte co-culture models develop high junctional tightness and express efflux transporters

Bovine brains have been used as a source for BCEC since 1983.4 Protocols for the generation of bovine BCEC differ between studies and laboratories, but two approaches dominate:

Size-selective filtering of microvessels followed by culture and use of first passage endothelial cells giving approximately 20–30 million cells per brain.53,56,91,107,167,168

Seeding of undigested microvessels followed by subculture up to passage 7 of endothelial clones sprouting from the capillaries.89,95,169

The subculture of endothelial cell clones expanded the yield of endothelial cells per brain by several fold and lowered contamination from pericytes and non-capillary endothelial cells, thus making the model more suitable for high-throughput studies.90

Most studies apply the bovine brain endothelial cells in contact or non-contact co-culture with astrocytes, but a triple co-culture including endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes has also been developed giving a slight reduction in Lucifer yellow permeability.101

Primary cultures of bovine BCECs display high TEER both in mono-cultures (up to averages around 800 Ω cm2)5,170 and in co-cultures with astrocytes (averages often exceeding 1000 Ω cm2 up to 2500 Ω cm2)53,89–91,107,166,168 with values on single filters up to 3000 Ω cm2.53 This reflects a high expression and junctional localization of claudin-5, ZO-1, and occludin.5,63,90,95,107,171–175 Small molecule permeability is reported in the range of 0.4–15 × 10−6 cm/s depending on the compounds examined, the methods applied, and the TEER of the model5,53,63,–89,91,95,101,107,166,168,171,176–178 (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Bovine in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Morphology, tightness and astrocyte/pericyte induction.

| Model type | Endothelial morphology | Junction Claudins | ∼TEER (Ohm·cm2) (mean values) | Permeability 10−6 (cm/s) | Occludin/ZO proteins | Astrocyte induction | Pericyte induction | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary bovine BCEC/rat astrocyte co-culture | Spindle (conventional media) Cobblestone (highly buffered media) | 5 (ICC, WB) 1 (mRNA) | 600–800 (conventional media) 1600 (highly buffered media) | 0.5 (mannitol) | Occludin (ICC) | Increased TEER and P-gp expression in coculture with rat astrocytes Changes in endothelial morphology in contact and non-contact co-culture | – | 91,107, 167,188 |

| Primary bovine BCEC (clonal selection)/ rat astrocyte coculture | Spindle shape | 1 and 5 (ICC) | 800 | 6–12.5 (sucrose) | ZO-1 and Occludin (ICC) | Increased TEER and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity in co-culture with rat astrocytes | Slight decrease in PLY when cultured in non-contact co-culture | 89, 90,101 |

| Primary bovine BCEC (clonal selection) monoculture | Spindle shape | 1 and 5 (ICC) | – | 5.8 (sucrose) | ZO-1 and Occludin (ICC) | – | – | 95 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

Astrocyte(+); mixed glial culture dominated by astrocytes.

The highly differentiated junctions make the model useful for examination of tight junction modulation and studies of passive permeability of drug compounds.56,149,174,175,179–187

P-gp has been shown to be functionally active in the cultured bovine endothelial cells both by accumulation assays and by bi-directional transport experiments.53,101,167,189–194 Protein expression and functional activity of BCRP and Mrp-1, -4, -5, and -6 have also been demonstrated.25,53,195–197 Mrp -4, -5, and -6 mRNA transcripts were detected in bovine brain endothelial cell mono-cultures and in co-culture with glial cells, with Mrp-6 being up-regulated in co-culture with pericytes.197 The same transcripts were found in endothelial cells in triple culture with pericytes and glial cells101 (see Table 7). Warren et al.158 profiled mRNA expression in a range of ABC transporters compared to human expression levels. The relative expression profiles were comparable between human and bovine brain endothelial cells, although the absolute expression levels varied considerably.

Table 7.

Bovine in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Receptor and transporter expression and function.

| Model type | ABC transporter expression/function | Vectorial net transport of ABC substrates | TFR expression/ function | LAT-1 expression/ function | Glut-1 expression/ function | MCT-1 expression/ function | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary bovine BCEC/rat astrocyte coculture | P-gp, BCRP and Mrp-1 (ICC, mRNA) Inhibitor data on transport | ER of 2.5 for digoxin ER of 4.5 for estrone-3-sulphate ER of 2.4 for etoposide | WB Trans-endothelial transport of holo-transferrin | mRNA | mRNA | – | 53,91,107 |

| Primary Bovine BCEC (clonal selection)/ rat astrocyte coculture | P-gp (WB) Inhibitor data on uptake | ER of 2 for vincristine | Trans-endothelial transport of radiolabelled holo-transferrin | High Pleucine relative to Psucrose | High PGlucose relative to Psucrose | – | 89,90,171,177 |

| Primary bovine BCEC (clonal selection) monoculture- | P-gp (ICC,WB), Mrp-1, -4 and -5 (WB) Inhibitor data on Rhod 123 uptake and quinidine transport | – | – | – | – | – | 95,178 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

Bovine BBB models do not always perform well regarding transporter activity and high junctional tightness, and substantial variations occur between and even within laboratories utilizing the models. For instance, many reports have shown bovine BBB models with TEER values in the range of 30–150 Ω cm2 and/or lack of functional activity of both ABC and SLC-transporters known to be present at the BBB in vivo.149,166,173,198,199 Intra-laboratory variations are evident in a series of publications by the group of de Boer where TEER varies from high values around 800 Ω cm2 to around 150–300 Ω cm2,19,187,192,193 using the same model in the same laboratory. This is even clearer in a study by Helms et al.,53 where TEER averages varied from 327 ± 30 Ω cm2 to 2555 ±399 Ω cm2 across model batches within the same study. This emphasizes the need to thoroughly validate the models, especially when setting up a model in a new laboratory.

Bovine models have been applied in several studies investigating receptor-mediated endocytosis or transcytosis across the BBB focusing on the RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end-products),200 LDL-receptor,63,201 LRP-1,77,202 and the transferrin receptor.65,171,203,204

The bovine models have mostly been applied to study receptor-mediated transcytosis, paracellular permeability, and ABC-mediated efflux, whereas only few studies have characterized SLC transporter expression and function in the model. Rapid transcellular leucine and glucose transport have been demonstrated, which indicated functional expression of LAT-1 and Glut-1.177,205 LAT-1 RNA is highly expressed in freshly isolated bovine brain capillaries and induces tryptophan uptake when expressed in oocytes.29 However, the expression and function of LAT-1 have not been confirmed in the bovine BBB models, beyond mRNA expression being detected with conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR)107 and indirectly by a non-sodium-dependent, BCH inhibitable leucine uptake206 Other amino acid transporters investigated in the model are the sodium-dependent transporters B(0,+) (SLC6A14)206 and excitatory amino acid transporters-1/-2/-3 (SLC1A1-3),168 which were functionally active with polarized localization at the luminal and abluminal membrane, respectively. Saturable acetic acid transport has been shown in bovine brain endothelial cells, indicative of functional MCT-1 expression.207

BBB models based on primary endothelial cells of bovine origin are labor intensive and reproducibility between and even within labs may be an issue. A simplified model has been developed aiming to circumvent these drawbacks and make the model more suitable for high throughput screening.95 This led to easier establishment and culture, while the resulting model still displayed sucrose and Lucifer yellow permeabilities around 6 × 10−6 cm/s and expression of P-gp, Mrps, and claudin-5.95 The model was further simplified to a “ready-to-use” model, where endothelial cells were passaged to filter plates and frozen.178 This enables shipment of the model to other laboratories without the expertise and routine to establish a BBB model, while maintaining a BBB phenotype comparable to the simplified format mentioned above.

The porcine models – Mono-cultures develop high junctional tightness

Porcine brain endothelial cells (PBEC) were initially isolated by Mischeck et al.208 Two different isolation protocols have been developed and optimized in different labs. One is based on homogenization of entire brain hemispheres (after meninges and secretory regions have been removed) using sterile cutters followed by a dispase digestion. The digested suspension is centrifuged in dextran to separate microvessels from low-density material, and microvessels are incubated with collagenase/dispase to free endothelial cells. These are isolated by centrifugation on a percoll gradient and subcultured for one passage to increase cell yield and purity.105,208,209 The other protocol is based on mechanical homogenization of isolated gray matter followed by size-selective filtering through sequentially smaller nylon mesh (150 and 60 µm) to isolate microvessels. These are digested with collagenase/DNAse/trypsin, and endothelial cells are obtained by culturing microvessel fragments.106,210 Both methods have been used and characterized extensively and, although different, they have some common characteristics. Porcine models generally develop very high TEER in both mono-culture and astrocyte co-culture normally reaching 500 to 1500 Ω cm2.54,92,105,106,210–213 and sometimes up to 2500 Ω cm2.214,215 This is facilitated by removal of serum from the culture medium as well as addition of hydrocortisone.105 The high TEER translates into low permeability of small molecule compounds with sucrose permeabilities ranging from 0.2 to 8 ×10−6 cm/s57,104,106,209,211,214,216 and similar permeability of mannitol54,57,104,209,213 (see Table 8). Comparative studies with mono-cultures versus mono-cultures stimulated with astrocyte-conditioned media and contact or non-contact astrocyte co-cultures demonstrated that astrocytic influence increases junctional tightness, claudin-5 expression, and activity of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase.54,92,213,215–217 The effect of pericyte co-culture and astrocyte/pericyte triple culture has also been investigated in porcine models, where slight TEER increases were observed when rat or porcine pericytes were included relative to mono-cultures. However, the inclusion of pericytes in the triple culture model did not cause an additional increase in TEER relative to the endothelial/astrocyte co-culture.213

Table 8.

Porcine in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Morphology, tightness and astrocyte/pericyte induction.

| Model type | Endothelial morphology | Junction Claudins | ∼TEER (Ohm · cm2) (mean values) | Permeability 10−6 (cm/s) | Occludin/ ZO proteins | Astrocyte induction | Pericyte induction | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary porcine BCEC (isolation with enzymes) | Cobblestone | 5 (ICC,mRNA) | 250–790 | 6 (sucrose) | Occludin (ICC,mRNA) | Increased TEER and changed morphology by astrocyte co-culture | 54,106,215 | |

| Primary porcine BCEC (isolation including density centrifugation step) | Intermediate | 5 (ICC,WB) | 400–1500 | 0.6–1 (sucrose) 1.8 (mannitol) | ZO1 and Occludin, (ICC,WB) | Increased TEER and claudin-5 expression, decrease in Psucrose and changed morphology by astrocyte co-culture | Decrease in TEER by pericyte co-culture. However increase in TEER by co-culture with bFGF-treated pericytes. Increase in TEER by porcine pericytes in contact-co-culture | 92,104, 213,218–221 |

| Primary porcine BCEC in co-culture with rat astrocytes or astrocyte cell line | Cobblestone in mono-culture, change to spindle in co-culture. Intermediate in both mono and co-culture | 5 (ICC,WB) | 800–1800 | 0.6 (Lucifer yellow) | ZO1 and Occludin (ICC, WB) | Increased TEER and claudin-5 expression, decrease in Psucrose and PLY and changed morphology by astrocyte co-culture | 54,92,215 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

PBECs express tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and -2,92,210,222–225 claudin-5,92,106,214,225 and occludin,92,106,225–230 as determined by real time PCR, Western blotting, confocal- and electron microscopy. The well-differentiated tight junctions of the model make it ideal for examining tight junction expression and modulation, and it has been the model of choice to introduce impedance analysis as a technique to continuously measure TEER in BBB models.231,232

A recent quantitative proteomics comparison of isolated brain capillaries showed that endothelial cells from porcine brain capillaries express a range of BBB-phenotype ABC transporters, with the BCRP:Pgp ratio closer to that of monkey and human than shown by rodent brain capillaries.48 This is reflected in the ABC-transporter expression in porcine models, where P-gp, BCRP, and Mrps-1 and -4 are expressed at the mRNA and protein level.106,215,220,228,229 They mediate polarized transport of P-gp and BCRP substrates228,229,233,234 and limit the accumulation of P-gp, BCRP, and Mrp substrates.106,215,222,235,236 Efflux transporters are thus generally expressed and active in the PBEC models, although subtype specific Mrp functionality including polarization of expression has not been investigated in detail (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Porcine in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Receptor and transporter expression and function.

| Model type | ABC transporter expression/function | Vectorial net transport of ABC substrates | TFR expression/ function | LAT-1 expression/ function | Glut-1 expression/ function | MCT-1 expression/ function | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary porcine BCEC (isolation with enzymes) | P-gp Inhibitor data on uptake and transport BCRP (mRNA) | – | Binding of radiolabeled transferrin | High Pleucine relative to Psucrose | – | – | 106,212, 238,241 |

| Primary porcine BCEC (isolation including density centrifugation step) | P-gp (ICC,mRNA, WB) BCRP (mRNA, WB) Mrp-1 and -4 (mRNA, ICC) Inhibitor data on uptake for all | ER of 2.5 for paclitaxel ER of 4 for Mitoxantrone | – | – | – | – | 104,220,222, 233,234,236 |

| Primary porcine BCEC in coculture with rat astrocytes or astrocyte cell line | P-gp (WB) BCRP (WB) Inhibitor data on uptake for both | – | Uptake of Alexa-555 conjugated human transferrin | – | – | – | 92,215 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

SLC expression and function have not been characterized to a great extent in PBEC models. High Glut-1 and some degree of MCT-1 expression have been shown in isolated porcine brain capillaries,48 but their expression or functions have not been characterized. L-Leucine permeability has been shown to be relatively high compared to sucrose (approximately 12 ×10−6 cm/s versus 5 × 10−6 cm/s), which indicates LAT-1 expression, but it was not directly attributed to LAT-1 via inhibition studies or demonstrations of mRNA or protein expression.106 OAT-1 and OAT-3 (SLC22A6 and 22A8) have been shown to be expressed at mRNA and protein level in PBECs, and functional expression was demonstrated as glutaric acid efflux inhibitable by probenecid.237

PBEC models have been used to study macromolecule transport through the BBB, focusing mainly on receptor-mediated transport. Surface expression of transferrin receptor has been shown in PBECs using binding assays with radiolabeled transferrin,238 and PBECs have shown the ability to take up human transferrin labelled with Alexa-555.215 Other receptors investigated include the LDL receptor, the LRP-1, the mannose-6-phosphate receptor, and lactoferrin receptor.64,223,225,239,240 Arylsufatase A has been shown to cross porcine BCEC, without altering the monolayer integrity. Transport was low (around 0.02 % of the applied amount) but to some degree inhibitable by co-administration of mannose-6-phosphate, which indicated receptor-mediated transport via the mannose-6-phosphate receptor.223 Likewise, fusing arylsulfatase A with ApoB, ApoE-I, and ApoE-II caused significant increases in the transcellular transport, indicative of LDL receptor and/or LRP-1-mediated transcytosis.64

The human models – Establishment of models from renewable sources

BBB models based on primary cultured cells from human tissue have been reported (for instance Bernas et al.111). However, human brain tissue is difficult to acquire on a regular basis, which limits the possibilities to establish BBB models based on primary human BCEC. Some commercial vendors offer primary cultures of human brain endothelial cells(for instance Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (Kirkland, WA, USA) as used by Urich et al.242 and ScienCell Research Laboratories (San Diego, CA, USA) as used by Cucullo et al.243), but often with only sparse documentation on the source. Instead efforts have been made to create alternative models based on immortalized brain endothelial cells or human-derived stem cells.114–118 The different human immortalized endothelial cell lines published have different properties. In this review, focus has been given to the hCMEC/D3 cell line, as this is the most widespread and well characterized of the published cell lines.

The human immortalized endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3

Since its generation and initial characterization,114 more than 150 publications have applied and further characterized the hCMEC/D3 cell line, and it is thus a well characterized, easy to use in vitro model of the human BBB (for a recent review see244).

The hTERT/SV40-immortalized hCMEC/D3 clonal cell line is derived from human temporal lobe microvessels isolated from tissue resected during surgery for epilepsy. hCMEC/D3 cells form a contact-inhibited monolayer of elongated cells on collagen type I or type IV. hCMEC/D3 expresses junction-associated IgG-like proteins such as PECAM-1 and JAM-A, adherens and tight junction structural proteins such as VE-cadherin, claudin-3 and -5, and occludin, scaffolding proteins such as ß-catenin and ZO-1 and -2 as well as the cell polarity complex Par-3/Par-6/PKCz, which further contributes to the control of tight junction integrity and apico-basal polarity.114,124,245–251

hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers express the characteristic tight junction proteins of the BBB252; however, the expression level of claudin-5, which is important for junctional tightness, has been reported to be lower than in intact microvessels,242 although optimal culture conditions can improve this. This is reflected by TEER in the range of 30–50 Ω cm2 and permeability for sucrose, mannitol, urea, sodium fluorescein, and Lucifer yellow in the range of 20–90 × 10−6 cm/s were initially reported114,124,245,247,253,254 (see Table 10). Larger molecules have lower permeabilities in the range of 5–13 × 10−6 cm/s for 4 kDa dextrans and 0.2–0.3 × 10−6 cm/s for 70 kDa dextrans.114,247 Hence, the model in its basic state presents a barrier for large molecules, whereas small molecules relatively easily permeate the barrier.

Table 10.

Human in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Morphology, tightness and astrocyte/pericyte induction.

| Model type | Endothelial morphology | Junction Claudins | ∼TEER (Ohm·cm2) (mean values) | Permeability 10−6 (cm/s) | Occludin/ZO proteins | Astrocyte induction | Pericyte induction | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hCMEC3/D3 (immortalized human brain endothelial cells) in monoculture | Intermediate | 1 (mRNA, WB) 3 (ICC, mRNA, WB) 5 (ICC, mRNA, PROT, WB) 12 (ICC, WB) | 40 (standard culture) 200 (with hydrocortisone) | 27.5 (sucrose) 10–57 (fluorescein) 10–26 (LY) 25 (mannitol) | Occludin (mRNA, ICC,WB) ZO1 (ICC,PROT) | Slight increase in TEER by co-culture with human astrocytes | No changes in TEER | 103,114,247 ,248,250–255 |

| hPSC (human pluripotent stem cells) | cobblestone | 5 (ICC, WB) | 250 (monoculture)–700 (astrocyte co-culture) 5350 (pericyte –primed NPC-co-culture) | 0.6 (sucrose) | Occludin (ICC, WB) ZO1 (ICC) | Increase in TEER by co-culture with rat astrocytes and human NPC’s | Increase in TEER by co-culture with human brain pericytes | 118,256 |

| Cord blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells | Cobblestone | 1 (mRNA) 3 (mRNA) 5 (ICC, mRNA, WB) | 70 (monoculture) 160 (pericyte co-culture) | 10–20 (Lucifer yellow) | Occludin (ICC, mRNA, WB) ZO1 (ICC, mRNA) | Decrease in PLucifer yellow by co-culture with rat astrocytes. Increase in protein expression of P-gp, GLUT-1 and occludin | Increase in TEER and decrease in PLucifer yellow by co-culture with bovine brain pericytes | 116,117 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting; PROT: MS-based proteomics; TEER: transendothelial electrical resistance.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

Astrocyte(+); mixed glial culture dominated by astrocytes.

The barrier properties are dependent on the culture protocols, and tighter monolayers have been obtained by activating the Wnt/ß-catenin pathway,124 the Wnt/planar cell polarity pathway,245 or nuclear receptors.247 Under these conditions, TEER values above 300 Ω cm2 and Lucifer yellow permeabilities in the range of 10–20 × 10−6 cm/s have been reported.124,247,255 Co-culture with astrocytes and/or pericytes has also been shown to increase TEER, although only to a small degree (from 30 to 60 Ω cm2).103 Another approach has been to subject hCMEC/D3 monolayers to a physiological shear stress (about 5 dyn/cm2) in a microfluidic device, which increased TEER to 120 Ω cm2.257

Thus, a number of studies have shown that the junctional tightness of the hCMEC/D3 model may be improved. Future attempts to improve the tightness of the model should focus on co-culturing pericytes and astrocytes either in 2D103 or 3D258 and/or the presence of shear stress.

One hundred and forty-four SLC transporters have been detected in hCMEC/D3 cells at the transcript level, including SLC2A1 (Glut-1), SLC7A5 (LAT-1), and members of the SLC16 (MCT) family, many of them regulated by cytokines.254,259 In a proteomics study, Glut-1 was shown to be expressed at a level similar to freshly isolated human brain microvessels.252 The same study also revealed high levels of additional influx transporters and receptors, including MCT-1, the insulin receptor, and the transferrin receptor (see Table 11). This study did not detect LAT-1 at the protein level. However, uptake of gabapentin inhibitable by phenylalanine, BCH, and siRNA-mediated LAT-1 knockdown has been reported indicating functional LAT-1 expression in the model.260

Table 11.

Human in-vitro models of the blood–brain barrier. Receptor and transporter expression and function.

| Model type | ABC transporter expression/function | Vectorial net transport of ABC substrates | TFR expression/ function | LAT-1 expression/ function | Glut-1 expression/ function | MCT-1 expression/ function | Selected key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hCMEC3/D3 (immortalized human brain endothelial cells) | P-gp (mRNA, PROT, WB) BCRP (mRNA, PROT, WB) Mrp-1 (mRNA,WB, PROT) Inhibitor data on uptake for all MRP5 (mRNA) | – | PROT | Not detected in proteomics study. However, uptake of gabapentin inhibitable by LAT-1 inhibition has been shown | PROT | PROT | 114,252,260 |

| hPSC (human pluripotent stem cells) | P-gp (ICC, mRNA) BCRP (ICC, mRNA) Mrp-1 (ICC, mRNA) Mrp-2, 4 and -5 (mRNA) Inhibitor data on uptake and transport for all | – | mRNA | mRNA | ICC, mRNA, relatively high PGlucose compared to PSucrose | mRNA | 118,256 |

| Cord blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells | P-gp (ICC, mRNA, WB) Inhibitor data on uptake BCRP (mRNA) Mrp-1, -4 and -5 (mRNA) | – | mRNA | mRNA | mRNA | mRNA | 116,117 |

: not investigated; ICC: immunocytochemistry; WB: Western blotting; PROT: MS-based proteomics; BCRP: breast cancer resistance protein; Mrp: multidrug-resistance protein.

Note: The permeability value of the smallest tested compound in the study is given.

hCMEC/D3 cells express mRNA of 23 ABC efflux transporters, including P-gp, Mrp-4, and BCRP.254,261 P-gp and BCRP expression have further been documented at the protein level,261–263 and P-gp has been shown to be primarily localized at the apical membrane, where it limits apical to basolateral permeability of rhodamine.264 This polarized expression is controlled by the cell polarity complex Par-3/Par-6/PKCz.245

In conclusion, the hCMEC/D3 cell line constitutes an easy to use, thoroughly characterized model of human origin, which appears particularly well suited for drug uptake studies and for unravelling the response of brain endothelium to human pathogens and neuroinflammatory stimuli.265 However, its relatively low junctional tightness under routine culture conditions is still a challenge regarding its use for vectorial transport of small molecule compounds and will require further optimization.

In vitro BBB models generated from human stem cells

Recently, human brain endothelial cells have been derived from stem cell sources including human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)118 and human cord blood-derived stem cells of circulating endothelial progenitor and hematopoietic lineages.116,117 These sources could in principle provide renewable and scalable sources for human BBB models.

Human PSCs include both human embryonic stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of human blastocysts266 and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) obtained from reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state.267,268 BBB-like endothelial monolayers have been obtained with a co-differentiation protocol, in which hPSCs were first cultured in unconditioned media to co-differentiate into a mixture of endothelial cells and neural progenitor cells. This co-differentiation environment is hypothesized to create an embryonic-like brain environment, suitable to induce endothelial cell expression of some key BBB traits.118 Human brain endothelial cells were subsequently subcultured and maintained as virtually pure monolayers on collagen/fibronectin-coated transwell filters or plates.

The resulting hPSC-derived brain cell monolayers develop a restrictive barrier with expression of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 localized to cell–cell contact zones. Monolayers produce baseline TEER values of 250 Ω cm2 but can reach up to 1450 Ω cm2 when co-cultured with rat astrocytes.118 This translates into very low sucrose permeabilities of 0.6 × 10−6 cm/s, similar to the lowest permeabilities reported for bovine and porcine models53,92,104 and far below permeability values reported in primary human models (approximately 170 × 10−6 cm/s269 and below those with hCMEC/D3 (20 × 10−6 cm/s as discussed above) (see Table 10). In the same study, diazepam permeability was around 18 × 10−6 cm/s resulting in a permeability dynamic range (diazepam:sucrose) around 40 fold.118 Glucose permeability across the model was around 3.7 × 10−6 cm/s, approximately seven fold higher than for sucrose, suggestive of functional Glut-1 expression, but this has not been confirmed with functional inhibition studies. Protein expression of P-gp, BCRP and Mrp-1 has been shown with immunocytochemistry, and uptake and transport studies with rhodamine and doxorubicin in combination with ABC transporter inhibitors have shown functional and polarized expression of efflux transporters118,256(see Table 11). Combined, these data suggest downstream utility in drug screening assays, although more validation with a larger set of transporter substrates is required. Likewise, receptor expression and function have not been studied in detail in the model, although a range of receptors including transferrin, insulin, and LDL- receptors have been shown at the mRNA level.118

Alternative human stem cell models based on cord blood-derived stem cells have been developed. These utilize different differentiation protocols, either based on pericyte117 or astrocyte116 co-culture. Both models show endothelial cell phenotype and expression of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1. The pericyte co-culture reaches significantly higher junctional tightness than the astrocyte co-culture with a Lucifer yellow permeability around 10 × 10−6 cm/s and TEER around 180 Ω cm2 compared to a Lucifer yellow permeability of 22 × 10−6 cm/s and TEER below 60 Ω cm2 in the astrocyte co-culture (see Table 10). P-gp, BCRP, and Mrp-1, -2, -4, and -5 as well as transferrin receptor and RAGE and a range of SLC transporters including Glut-1 and LAT-1 were found at the mRNA level in pericyte co-cultures.117 Astrocyte co-cultures also showed expression of Glut-1, P-gp and BCRP, and the protein expression levels of Glut-1 and P-gp were found to be up-regulated by the astrocytes116 (see Table 11). As with the hPSC-derived model, the cord blood-derived models still lack validation regarding functional expression of transporters, efflux pumps, and receptors.

The stem cell-derived models offer the opportunity to study the dynamic changes that may occur during BBB development. For example, the current differentiation protocol for the hPSCs recapitulates developmentally relevant in vivo canonical Wnt signaling events between neural progenitor cells and endothelial cells.118,270,271 Similarly, the cord blood-derived endothelial cells are regulated by addition of Wnt3a or Wnt7a, resulting in increased TEER compared to un-stimulated monocultures.117 Furthermore, hPSC-derived brain endothelial cells exhibit significantly increased barrier phenotype in response to retinoic acid (TEER increases up to 2940 ± 800 Ω cm2),256 a hormone implicated in BBB regulation.42,272,273

The stem cell-based models could additionally be used to interrogate other signaling pathways and developmental events such as those with the interacting cells of the NVU.116,117,256 Moreover, with the hPSC system, it would also be possible to model diseased NVU phenotypes using endothelial and neural cells derived from patient-specific iPSCs with diseased genetic backgrounds.274 One caution when using lentivirally reprogrammed iPSCs is that they exhibit random genomic integration of pluripotency factors that could potentially affect the ultimate differentiated phenotype.275 However, hPSC-derived brain endothelial cells have been successfully derived from both human embryonic stem cells118,266 and iPSCs generated by non-integrating methods118,276 to avoid such complications.

In conclusion, the stem cell-derived BBB models represent a promising tool for both mechanistic studies of human brain endothelial cell biology and as a screening tool for CNS-drug permeability studies. However, the models have not yet been extensively characterized, because of the short time period they have been available. Hence, future studies should aim at characterizing these models regarding BBB features as well as validating the reproducibility and “ease of culture” of the models.

Conclusion

Techniques for in vitro culture of brain endothelial cells have been developed continuously over the past 40 years. Endothelial cell cultures have been derived from a number of species, using a variety of isolation and culture methods, which have been optimized for the species in question. This has resulted in a range of in vitro BBB models with different properties, which makes comparisons between different studies and planning of new studies challenging. However, as summarized in this review, the in vitro models have proven to be valuable tools in studies concerning BBB development, physiology, pathophysiology, toxicology, and CNS-drug development. The right choice of model for a study will depend on the research question at hand. Brain endothelial cells of bovine and porcine origin form tight endothelial monolayers with a high transendothelial resistance and are suited for investigations of small molecule transport through the BBB. They display functional efflux transporter activity as well as restrictive tight junctions, resulting in vectorial transport of P-gp and BCRP substrates, and may also be suited for studies of polarized localization of for instance specific receptors or transporters, since the high junctional tightness helps establish good apical:basal polarity. Given that a reliable source of animals is available (abattoir or animal facility), large quantities of endothelial cells can be obtained allowing screening studies. On the other hand, the proteins expressed by bovine and porcine models differ in sequence from their human homologues and this may in some cases translate to differences in affinity and transport rate.50,158 This also poses a challenge when investigating therapeutic antibodies designed to target BBB-expressed proteins, since these are often designed to react with human or mouse and rat homologues. Murine or human endothelial cell culture models may be preferable in these types of studies.

Brain endothelial cell cultures of mouse or rat origin have the advantage of being from species which are thoroughly characterized and are often used as first choice for preclinical studies. While rat and mouse brains are easy to obtain, the generally low yield of endothelial cells from these species has been an obstacle for the routine use of murine endothelial cell models, although quite advanced endothelial cultures can be obtained in dedicated laboratories, e.g. the triple co-culture rat model. Since this model incorporates the three main cell types of the neurovascular unit, it also allows detailed NVU-signaling studies. The establishment and characterization of the immortalized mouse endothelial cell lines such as bEND.3, bEND.5, or cEND can circumvent the problem of low yield of endothelial cells if the cell line has the right characteristics for the given study, but the cell lines have not been widely used so far. Their potential use in preclinical studies does however warrant further attention.

Primary cultures of human brain endothelial cells, reflecting the fully differentiated phenotype, would be ideal for drug development and preclinical studies. It is however difficult to obtain fresh healthy brain tissue on a regular basis. The establishment and characterization of the human immortalized cell line, hCMEC/D3, have given researchers a tool for investigating human brain endothelial cell transporters, receptors, signalling pathways, and metabolism without the issues of availability and variability between isolation batches. The relatively low tightness of the monolayers formed by the hCMEC/D3 cells can be improved by optimizing culture conditions, however not to levels matching the bovine, porcine, or human stem cell-derived models. The hCMEC/D3 cells therefore have some limitations when it comes to vectorial transport studies of small molecules, but may perform well in mechanistic studies of expressed transporters and receptors.

The recent reports describing techniques for the generation of endothelial cell cultures from human stem cells are steps towards a human cell culture model of the brain endothelium. The differentiated endothelial cells form tight monolayers with high electrical resistance and have functional expression of efflux transporters. The human stem cell models are presently being characterized and refined and will, if proven to be easy to handle and reproducible, present great opportunities for researchers in the field.

Open questions and suggestions for future studies

Much progress has been made during the last four decades in the development of in vitro models of the BBB. The field has advanced in parallel with advances in BBB biology and our increased understanding of the roles of the cell types in the neurovascular unit. There are still a lot of open questions within the field of in vitro BBB models, and these cannot be answered without a deeper understanding of the biology of the native barrier/the neurovascular unit. We have outlined some of these below, as an inspiration for future research and as a reminder to those already in the field.

Expression and function of SLC-type uptake transporters

A recent perspectives paper summarizes research trends within the field of SLC-proteins and argues that the field is generally under-studied compared to their biological relevance.277 A similar argument can be made regarding SLCs at the BBB. Traditionally, when characterizing transporter expression in BBB models, the ABC-type efflux transporters have gained most attention. Thus, most models today are well characterized concerning at least P-gp and BCRP expression, whereas it is a common feature of the in vitro BBB models that SLC uptake transporters are relatively uncharacterized, or have low expression levels, as described in the previous sections. It is known that some marketed drugs are transported by SLC-transporters, for instance L-dopa and gabapentin,278 which makes the functional expression of LAT-1 and other SLC transporters important in a BBB model for drug compound screening purposes or for studies regarding regulation of nutrient and micronutrient transporters. Characterization can be performed by a combination of transendothelial transport experiments in combination with substrate and inhibitor profiling, as well as immunocytochemistry showing expression of the transporter in question. Ideally, transporter localization should be confirmed by comparing the localization in intact capillary endothelial cells with the localization in endothelial cells in culture. LAT-1 and Glut-1 are good starting candidates because of their important physiological functions. However, other SLC-transporters may be equally important at the BBB and may have potential as drug targets/transporters. The growing number of studies on the in vivo BBB transcriptome and proteome will assist in directing focus to the SLC transporters of highest significance for future characterization.

The role of other NVU cells, especially pericytes, in BBB models

Pericytes have proven to be essential for the formation of the BBB in vivo,41,42 but the effects of pericytes in vitro vary between BBB models. Results from rat models have shown increased TEER in triple cultures compared to astrocyte-endothelial co-cultures.97 A similar TEER increase was seen in mouse endothelial cells (pericyte co-culture relative to endothelial mono-culture),42 whereas data from pig models have shown reduced TEER in endothelial cells co-cultured with pericytes due to an induction of MMPs.221 The differentiation state of pericytes in vitro was found to be decisive for the effect of co-culture, with pericytes treated with bFGF causing a slightly increased TEER, whereas TGFβ-treated pericytes caused a decrease in TEER.219 However, pericytes were not found to affect tight junction protein expression in vivo, where the main effect of pericytes was to decrease expression of certain genes favoring vascular permeability.42 Thus, the current understanding of pericyte effects in BBB-cell culture models is incomplete. The stem cell models may prove to be effective tools to gain knowledge of signaling effects of pericytes (and other cells of the NVU) and their importance in different stages of BBB induction and maintenance, especially if coupled to detailed transcriptome and proteome analysis, where induction and silencing of individual genes and proteins by the different NVU cells at different development stages can be identified. This kind of knowledge may feed back into the routine use of primary cell cultures to also improve their BBB characteristics. Much of the induction of primary cell models today is dependent on stimulation by cAMP-analogues and steroids (hydrocortisone or dexamethasone). The full effects of these barrier-modulating additives are not known, and the overall BBB characteristics may be better mimicked if barrier-modulating agents can be substituted with induction from NVU cells.

Disease models of the BBB

It is well known that the BBB is a dynamic barrier that changes properties under different conditions. The BBB is affected by different disease states, for example stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and multiple sclerosis.279–283 Many in vitro studies on the ischemic BBB have been performed using oxygen-glucose deprived culture conditions and thus quite well-validated models of the BBB during ischemic insults exist.131,143,284–287

Likewise, several models for the BBB under cancer conditions have been developed, for instance by co-culturing BCEC with the glioblastoma cell lines, RG-2 or C6,94,130,155,181,288 and BBB models have been applied to study adhesion and transmigration of metastatic cancer cells.289–293 The BBB changes properties during Alzheimer’s disease, which contributes to- and may even be a leading cause of neurodegeneration.294,295 In vitro BBB models have been extensively applied to investigate changes caused by the Alzheimer’s disease environment and to investigate the ability of the BBB to transport amyloid beta (see reviews296,297). Using cells from rat and mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, it may be possible to decipher the responses of the BBB during the development of the disease, at the molecular and cellular levels.

Diseases caused by gene-disorders have not been well modelled so far. The human stem cell models may present possibilities to facilitate development of new models from iPSCs isolated from patients with specific CNS-pathologies. Alternatively, mouse and rat models based on endothelial cells isolated from knock-out or transgenic animals may provide useful models for specific disease states, which have been demonstrated with endothelial cells isolated from PPAR-alpha-deficient mice.298

The well-documented changes in BBB properties during different disease states highlight the fact that the BBB should not be considered a static barrier that presents the same obstacle for every disease condition. BBB permeability and drug permeation may change with different pathologies, as is the case of stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and some cancer forms, but in most disease conditions drug permeation remains hindered or even decreases, for instance due to an up-regulation of P-gp as observed in epilepsy.299 Thus, in vitro models mimicking different pathologies should be refined and validated to improve translation of data to the in vivo settings.

Funding

Hans Christian Helms and Birger Brodin wishes to acknowledge the funding received from the Lundbeck Foundation via the project grant “Research Initiatives in Brain Barriers and Drug Delivery” (RIBBDD).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Roméo Cecchelli is one of the holders of the patent WO 2014/203087 A1: A human blood–brain barrier model derived from stem cells, discussed in the review. Mária A. Deli is a scientific consultant to PharmaCo-Cell Co. Ltd, Japan, and one of the holders of the patent WO2007072953 on the in vitro rat triple BBB model discussed in the review.

Authors’ contributions

Hans Christian Helms and Birger Brodin prepared the outline of the manuscript. Malgorzata Burek and Carola Förster drafted the section “Mouse models – Immortalized and primary mouse brain endothelial cultures.” Maria Deli drafted the section “Rat models – Mono-, co-, and triple cultures of rat BCEC.” Elodie Vandenhaute, Romeo Cecchelli, Hans Christian Helms, and Birger Brodin drafted the section “Bovine models – Astrocyte co-culture models develop high junctional tightness and express efflux transporters.” The section “The porcine models – Mono-cultures develop high junctional tightness” was drafted by N. Joan Abbott and Hans Joachim Galla. Romeo Cecchelli, Pierre-Olivier Couraud, Ignacio A. Romero, Eric V. Shusta, Matthew J. Stebbins, Elodie Vandenhaute, and Babette Weksler drafted the section.” The human models – Establishment of models from renewable sources. Remaining sections and figures were drafted by Hans Christian Helms and Birger Brodin. All authors participated in the feedback and writing process following the initial drafting of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mathiisen TM, Lehre KP, Danbolt NC, et al. The perivascular astroglial sheath provides a complete covering of the brain microvessels: an electron microscopic 3D reconstruction. Glia 2010; 58: 1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbott NJ. Anatomy and physiology of the blood–brain barriers. In: Hammarlund-Udenaes M, de Lange ECM, Thorne RG. (eds). Drug delivery to the brain, New York, NY: Springer, 2014, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006; 7: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman PD, Ennis SR, Rarey KE, et al. Brain microvessel endothelial cells in tissue culture: a model for study of blood-brain barrier permeability. Ann Neurol 1983; 14: 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin LL, Hall DE, Porter S, et al. A cell culture model of the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol 1991; 115: 1725–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe EA, Hoyer LW, Nachman RL. Synthesis of antihemophilic factor antigen by cultured human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 1973; 52: 2757–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorovini-Zis K, Huynh HK. Ultrastructural localization of factor VIII-related antigen in cultured human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem 1992; 40: 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]