Abstract

Objective. The aim of our study was to evaluate the relation of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) infection with the risk of atherosclerosis (AS). Methods. A systematic literature search was performed through three electronic databases. The pooled odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess the effect of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection on AS risk. Results. 17 studies were available for meta-analysis of HSV-1 infection and AS risk and seven studies for meta-analysis of HSV-2 infection and AS risk. Subjects exposed to HSV-1 infection exhibited an increased risk of AS (OR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.40–2.23; P < 0.001). And consistent elevated AS risks for HSV-1 positive subjects were found in all subgroup analysis of disease type, region, male proportion, and age. HSV-2 positive subjects demonstrated significantly increased AS risk (OR = 1.37; 95% CI: 1.13–1.67; P < 0.005). In subgroup analysis, elevated AS risks were only observed in myocardial ischemia group, male proportion >60% group, and age ≤60-year-old group. Conclusion. Our meta-analysis indicated that HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection could increase the risk of contracting AS.

1. Background

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a major public health problem worldwide that leads to various life-threatening complications, such as coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease [1, 2]. Traditional risk factors include hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and a positive family history, but these do not fully explain the extent and severity of the conditions [3]. In recent years, numerous studies have implicated that pathogen burden might play an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, for example, Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) [4–6].

HSV infection was widespread in the developed countries, with a prevalence of between 35% and 40% [7]. The data showed that the prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 is 37% and 28%, respectively [7]. HSV was first proposed to be a risk factor for AS several decades ago when a chicken herpesvirus led to occlusive AS of large muscular arteries in an animal model [8]. Subsequent molecular biology and epidemiology studies have strengthened the hypothesis that HSV is an important risk factor in the development of AS in humans. The atherogenic mechanisms of HSV may involve increasing adherence of leukocytes to endothelium, inducing lipid accumulation in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and contributing to deposition of thrombin in atherosclerotic plaques [9–11].

Recently an increasing number of epidemiologic studies have investigated the association between HSV infection and AS risk by testing HSV antibodies [12]. Siscovick et al. revealed that HSV-1 infection was associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of incident MI and death from coronary heart disease [13]. Kis et al. detected increased levels of HSV-1 antibodies in patients with acute ischemic stroke, suggesting an association of HSV-1 infection with the disease [14]. The data of Guan et al. showed a higher prevalence of antibodies against HSV-2 in the subjects with acute myocardial infarction [15]. However, there were still some studies demonstrating no relationship between HSV infection and atherosclerosis [16, 17]. Given the controversial results of these studies, we deemed it necessary to conduct a quantitative and systematic assessment with rigorous methodology to further evaluate the potential role of HSV infection in the development of AS. We performed a meta-analysis to explore the relationship between HSV-1 and HSV-2 and AS risk.

2. Methods

2.1. Publication Search

We searched the databases of PubMed, Web of Science, and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) for articles on any relationship between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection and the risk of developing AS. The last search date was March 15, 2015. The following key terms were used: “Herpes Simplex Virus OR HSV” and “atherosclerosis OR myocardial ischemia OR ischemic heart disease OR coronary artery disease OR angina OR myocardial infarction OR stroke OR cerebral ischemia OR carotid artery disease OR peripheral artery disease.” The references cited in the research papers were further searched manually for potentially available publications.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

(1) The study is a case-control design. (2) The study evaluates the association between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection and AS risk. (3) The study confirms the diagnosis of the atherosclerotic diseases. (4) The study clearly supplies the values (or percentage) of positivity for HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection in cases and controls, respectively. (5) The study is published in English or Chinese.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data from these studies were extracted by two of the authors (Yu peng Wu and Dan dan Sun) independently using a standardized form, who reached a consensus on all items. The following data were collected from each study: first author, year of publication, country, region, disease type, mean age, male proportion, detection method of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection, sample size, and the positivity or negativity for HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection in cases and controls, respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to assess the association of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection with AS risk. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed with the χ 2-based Q test and I 2 [18]. When heterogeneity was not an issue (P > 0.10), a fixed-effect model with the Mantel-Haenszel method was used [19]. Otherwise, a random-effect model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was used [20]. Meanwhile, subgroup analysis was conducted for different geographic regions, male proportion, mean age, and disease types (divided into myocardial ischemia and other types of AS). To explore sources of heterogeneity across studies, we conducted logistic metaregression using the following study characteristics: region, test method, and positivity for HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection in controls. In addition, publication bias was evaluated qualitatively by performing funnel plots and was assessed quantitatively by Begg's test and Egger's test, respectively (P < 0.05 was considered representative of statistically significant publication bias) [21, 22]. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12.0 software (Stata, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

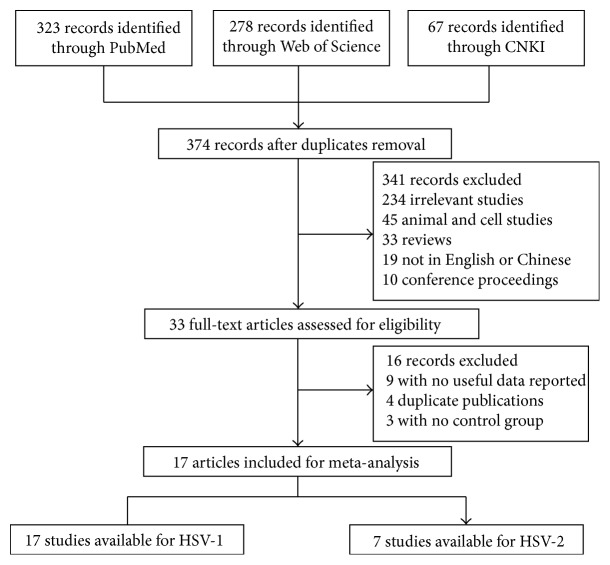

Applying the search strategy, 374 papers were found. The titles, abstracts, and full texts of all retrieved articles were reviewed in accordance with the defined criteria. One study by Mendy et al. was excluded because the atherosclerotic disease was diagnosed by self-reported questionnaire, which could be subject to recall bias or misclassification [23]. Overall, 17 studies including a total of 3488 cases and 4241 controls were available for this analysis [6, 13–17, 24–34]. Among these, seven studies with 1810 cases and 1050 controls were available for HSV-2 infection analysis, and all 17 were available for analysis of HSV-1 infection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for identification of studies.

The characteristics of the selected studies were listed in Tables 1 and 2. Of the 17 studies, 14 were published in English and three were written in Chinese. The sample sizes ranged from 15 to 1532. The controls were randomly selected and frequency-matched with the cases on age, region, and gender. Several methods were used to detect HSV-1 and HSV-2 specific antibody, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), solid-phase radioimmunoassay (SPRIA), and western blotting (WB). The diseases included myocardial ischemia, stroke, carotid artery disease, and mixed AS lesions (coronary, cerebral, carotid, and peripheral artery involvement) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of literatures included in the meta-analysis concerning HSV-1.

| First author | Year | Country | Region | Disease type | Test method | Male proportion | Age | Sample size | Case size | Control size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 (+) | HSV-1 (−) | HSV-1 (+) | HSV-1 (−) | |||||||||

| Jafarzadeh [24] | 2011 | Iran | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 59% | 54 | 180 | 73 | 47 | 20 | 40 |

| Heltai [25] | 2004 | Hungary | European | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | — | — | 129 | 59 | 24 | 32 | 14 |

| Vahdat [26] | 2007 | Iran | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 49% | — | 1754 | 198 | 24 | 1327 | 205 |

| Mundkur [17] | 2012 | UK | European | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 68% | 53 | 866 | 240 | 193 | 214 | 219 |

| Prasad [27] | 2002 | America | American | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 61% | 56 | 375 | 211 | 35 | 102 | 27 |

| Georges [28] | 2003 | Germany | European | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 73% | 62 | 1324 | 922 | 69 | 280 | 53 |

| Lindberg [29] | 1997 | Sweden | European | Carotid artery disease | SPRIA | — | — | 534 | 198 | 69 | 190 | 77 |

| Siscovick [13] | 2000 | America | American | Myocardial ischemia | WB | 63% | 74 | 618 | 191 | 22 | 333 | 72 |

| Guan [15] | 2012 | China | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 62% | 56 | 252 | 71 | 31 | 60 | 90 |

| Zhu [30] | 2000 | America | American | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 63% | 57 | 233 | 133 | 25 | 59 | 16 |

| Kis [14] | 2007 | Hungary | European | Stroke | ELISA | 58% | 52 | 111 | 24 | 35 | 8 | 44 |

| Adam [31] | 1987 | America | American | Mixed AS lesions | SPRIA | 100% | 58 | 226 | 75 | 38 | 69 | 44 |

| Sorlie [16] | 2000 | America | American | Myocardial ischemia | SPRIA | 52% | 55 | 726 | 166 | 55 | 379 | 126 |

| Al-Ghamdi [6] | 2012 | Saudi Arabia | Asian | Mixed AS lesions | ELISA | 64% | 56 | 90 | 72 | 3 | 14 | 1 |

| Pan [32] | 2005 | China | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 48% | 62 | 127 | 46 | 16 | 22 | 43 |

| Pan [33] | 1999 | China | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 70% | — | 60 | 24 | 6 | 22 | 8 |

| Liu [34] | 2004 | China | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 73% | 67 | 124 | 72 | 21 | 19 | 12 |

HSV-1: herpes simplex virus type 1; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; SPRIA: solid-phase radioimmunoassay; WB: western blot; AS: atherosclerosis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of literatures included in the meta-analysis concerning HSV-2.

| First author | Year | Country | Region | Disease type | Test method | Male proportion | Age | Sample size | Case size | Control size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-2 (+) | HSV-2 (−) | HSV-2 (+) | HSV-2 (−) | |||||||||

| Jafarzadeh [24] | 2011 | Iran | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 59% | 54 | 180 | 34 | 86 | 17 | 43 |

| Georges [28] | 2003 | Germany | European | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 73% | 62 | 1324 | 139 | 852 | 27 | 306 |

| Lindberg [29] | 1997 | Sweden | European | Carotid artery disease | SPRIA | — | — | 534 | 64 | 203 | 66 | 201 |

| Guan [15] | 2012 | China | Asian | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 62% | 56 | 252 | 56 | 46 | 57 | 93 |

| Zhu [30] | 2000 | America | American | Myocardial ischemia | ELISA | 63% | 57 | 233 | 84 | 74 | 32 | 43 |

| Kis [14] | 2007 | Hungary | European | Stroke | ELISA | 58% | 52 | 111 | 23 | 36 | 14 | 38 |

| Adam [31] | 1987 | America | American | Mixed AS lesions | SPRIA | 100% | 58 | 226 | 30 | 83 | 31 | 82 |

HSV-2: herpes simplex virus type 2; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; SPRIA: solid-phase radioimmunoassay; AS: atherosclerosis.

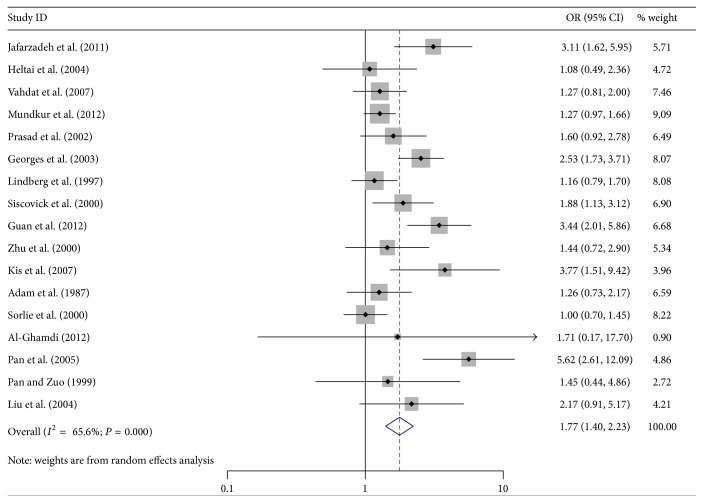

3.2. Effect of HSV-1 Infection on AS Risk

The relationships between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection and the risk of AS were shown in Table 3. Overall, there was statistical evidence of significantly elevated AS risk associated with HSV-1 infection (OR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.40–2.23) (Figure 2). In terms of stratified analysis by disease type, there were significant elevated risks in both myocardial ischemia and other types of AS for HSV-1 infection (myocardial ischemia: OR = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.40–2.40; other types of AS: OR = 1.73; 95% CI = 1.02–1.83). When stratified by region, AS risks were elevated in Asians, Europeans, and Americans (Asians: OR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.57–3.97; Europeans: OR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.09–2.42; Americans: OR = 1.32; 95% CI = 1.06–1.65). And consistent elevated AS risks for HSV-1 positive subjects were found in all subgroup analysis of age and male proportion (male proportion ≤60%: OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.19–4.30; male proportion >60%: OR = 1.80; 95% CI = 1.40–2.31; age ≤60-year-old: OR = 1.74; 95% CI = 1.26–2.41; age >60-year-old: OR = 2.52; 95% CI = 1.92–3.30).

Table 3.

Pooled OR and 95% CI of stratified meta-analysis.

| Variables | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 (%) | P Het | N | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 (%) | P Het | |

| Total | 17 | 1.77 (1.40–2.23) | <0.001 | 65.6 | <0.001 | 7 | 1.37 (1.13–1.67) | 0.002 | 38.2 | 0.138 |

| Disease type | ||||||||||

| Myocardial ischemia | 13 | 1.83 (1.40–2.40) | <0.001 | 69.6 | <0.001 | 4 | 1.66 (1.28–2.15) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.409 |

| Other types of AS | 4 | 1.37 (1.02–1.83) | 0.035 | 45.8 | 0.137 | 3 | 1.05 (0.77–1.41) | 0.777 | <0.001 | 0.410 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| Asian | 7 | 2.49 (1.57–3.97) | <0.001 | 61.3 | 0.017 | 2 | 1.47 (0.75–2.86) | 0.261 | 59.4 | 0.116 |

| European | 5 | 1.63 (1.09–2.42) | 0.017 | 73.2 | 0.005 | 3 | 1.40 (0.87–2.26) | 0.168 | 61.9 | 0.072 |

| American | 5 | 1.32 (1.06–1.65) | 0.014 | 11.9 | 0.338 | 2 | 1.22 (0.82–1.83) | 0.323 | 22.2 | 0.257 |

| Male proportion | ||||||||||

| ≤60% | 5 | 2.26 (1.19–4.30) | 0.013 | 84.0 | <0.001 | 2 | 1.26 (0.75–2.13) | 0.381 | 3.6 | 0.308 |

| >60% | 10 | 1.80 (1.40–2.31) | <0.001 | 47.9 | 0.044 | 4 | 1.61 (1.25–2.07) | <0.001 | 26.8 | 0.251 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| ≤60-year-old | 9 | 1.74 (1.26–2.41) | 0.001 | 67.4 | 0.002 | 5 | 1.41 (1.08–1.85) | 0.012 | 14.9 | 0.320 |

| >60-year-old | 4 | 2.52 (1.92–3.30) | <0.001 | 46.5 | 0.132 | 1 | 1.85 (1.20–2.85) | 0.005 | — | — |

HSV-1: herpes simplex virus type 1; HSV-2: herpes simplex virus type 2; AS: atherosclerosis; OR: odds ratio; P Het: the P value of heterogeneity; —: no data. The results were in bold, if the 95% CI excluded 1 or P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the association between HSV-1 infection and atherosclerosis.

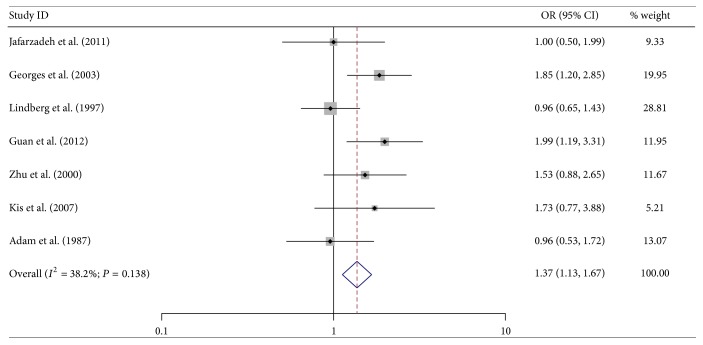

3.3. Effect of HSV-2 Infection on AS Risk

In total population, HSV-2 positive subjects demonstrated significantly elevated AS risk when compared with the negative ones (OR = 1.37; 95% CI = 1.13–1.67) (Figure 3). In terms of stratified analysis by disease type, increased risk was only observed in myocardial ischemia and not in other types of AS (myocardial ischemia: OR = 1.66; 95% CI = 1.28–2.15). We also performed stratified analysis by region, age, and male proportion. Significantly elevated risks were observed in male proportion >60% group and age ≤60-year-old group (male proportion >60%: OR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.25–2.07; age ≤60-year-old: OR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.08–1.85) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the association between HSV-2 infection and atherosclerosis.

3.4. Heterogeneity

There was heterogeneity among studies on HSV-1 infection but not in studies on HSV-2 infection (HSV-1 infection: P < 0.001; I 2 = 65.60%; HSV-2 infection: P = 0.138; I 2 = 38.2%). To explore sources of heterogeneity across studies, we compared HSV-1 infection according to region of origin, test method, and positivity for HSV-1 infection in controls. We found that the region (P < 0.05), but not test method and the positivity for HSV-1 infection in controls (P > 0.05), might play a role in the initial heterogeneity, which could explain the I 2 value of 29% in the overall comparison of HSV-1 infection.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

There was no significant difference in the pooled OR estimated by omitting one study at a time, indicating that the final results of this meta-analysis were relatively stable and reliable (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/2630865). The Begg and Egger tests were conducted to evaluate publication bias. Both revealed no evidence of publication bias in our study; the results were shown in Table 4, Figure S1, and Figure S2.

Table 4.

The results of Begg's and Egger's test for publication bias.

| HSV type | Begg's test | Egger's test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z value | P value | t value | P value | |

| HSV-1 | 1.69 | 0.091 | 1.71 | 0.107 |

| HSV-2 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.15 | 0.887 |

HSV: herpes simplex virus; HSV-1: herpes simplex virus type 1; HSV-2: herpes simplex virus type 2.

4. Discussion

Herpesvirus has been implicated in the inflammatory atherosclerotic process [35]. Chronic activation of inflammation by herpesvirus infection is hypothesized to promote atherosclerosis and thrombosis. As the major subtypes of herpesvirus, HSV-1 and HSV-2 have been a concern in relation to AS for many years. However, the existing data are somewhat conflicting. Hence, we deemed it necessary to take a quantitative approach by combining the results of various studies and provide what to our knowledge is the first meta-analysis evaluating the effect of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection on AS risk.

In the overall analysis, significant increased risk was observed for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection, indicating that HSV infection may play an important role in the process of atherogenesis. Some mechanistic studies may explain certain relationships. In 1991, Etingin et al. demonstrated that the endothelial cells infected by HSV might express the adhesion molecule GMP140, which could mediate endothelial cell injury and inflammation [36]. Subsequently, Chirathaworn et al. showed that HSV enhanced the uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein in endothelial cells [37]. The atherogenic effect of HSV not only concerned the endothelial cells but also involved VSMCs. It had been reported that more saturated cholesteryl esters and triacylglycerols accumulated in VSMCs infected by HSV than in uninfected cells [38]. In addition, Key et al. concluded that HSV could contribute to deposition of thrombi on atherosclerotic plaques and induce coagulant necrosis by decreasing thrombomodulin activity and increasing tissue factor activity [39]. These in vitro studies demonstrated that HSV exerts effects in almost every step of atherogenesis.

Subgroup analysis suggested that both HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection had a significant risk effect in myocardial ischemia. Borderline significance was found for other types of AS in HSV-1 infection whereas no association was observed between HSV-2 infection and other types of AS. Many studies have reported the detection of HSV-1 DNA in human vascular tissue from different sites. Benditt et al. first found HSV-1 DNA in human vascular tissue from the ascending aorta in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery [40]. Subsequently, HSV-1 DNA was reported in coronary artery tissue. Chiu et al. detected HSV-1 DNA in plaques from occlusive carotid artery [41], and HSV-1 DNA was also found in atherosclerotic tissues from six types of atherosclerotic lesions by Shi and Tokunaga [42]. However, only one study, by Kotronias and Kapranos, reported the detection of HSV-2 DNA in coronary artery tissue [43]. These data might partially explain the different results from our subgroup analysis. Future studies concerning the association between HSV-2 infection and other types of AS should be performed to confirm our results.

In the stratified analysis of age and male proportion, we found no relationship of HSV-2 infection with risk of AS in male proportion ≤60% group. We presumed that gender difference might account for more than half of the reason. Males are more likely to suffer from AS than females [44]. And androgen appeared to be associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease by adversely affecting the plasma lipid and lipoprotein profile, producing thrombosis and cardiac hypertrophy [45].

Regarding the subgroup analysis of diverse regions, HSV-1 infection had risk effects on all three subgroups of Asians, Europeans, and Americans. However, the association of HSV-2 infection with AS did not reach statistical significance in any subgroup, possibly because of the limited number of studies and relatively small sample size in each subgroup (two studies of Asians, three studies of Europeans, and two studies of Americans). More well-designed studies with larger sample sizes should be conducted for future validation.

We are aware that this meta-analysis has its own limitations. First, only seven articles with 1810 cases and 1050 controls were available for HSV-2 analysis; the relatively small number of participants made it difficult to perform stratified analysis. Second, our meta-analysis was based on unadjusted estimates; OR adjusted for age and sex should be pooled to provide exact summary estimates if more specific data from studies become available. Third, significant heterogeneity existed in the overall comparison of HSV-1 infection, although we found that regional differences may account for this heterogeneity.

5. Conclusions

Our meta-analysis indicated that HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection potentially increases the risk of AS. However, further large-scale and well-designed studies, including different geographic regions and careful matching between cases and controls, are required to confirm these results.

Supplementary Material

This supplementary material consisted of one table (Table S1) and two figures (Figure S1 and Figure S2). Table S1 showed the ORs and 95% CI of sensitivity analysis concerning HSV-1 and HSV-2. It was no significant difference detected on the pooled OR which was estimated by omitting one study at a time. Figure S1 was Begg's funnel plots concerning HSV-1, and Figure S2 concerning HSV-2. The shape of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in the overall meta-analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partly by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Ref. no. 2015020506).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Yu peng Wu and Dan dan Sun performed statistical analysis, data interpretation, and wrote the paper. Yu peng Wu and Wen Liu analyzed the data and revised the paper. Dan dan Sun and Jun Yang conceived and designed this study and revised the paper.

References

- 1.Cullen P., Rauterberg J., Lorkowski S. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2005;(170):3–70. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27661-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viles-Gonzalez J. F., Fuster V., Badimon J. J. Atherothrombosis: a widespread disease with unpredictable and life-threatening consequences. European Heart Journal. 2004;25(14):1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhlestein J. B., Horne B. D., Carlquist J. F., et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity and C-reactive protein have independent and combined predictive value for mortality in patients with angiographically demonstrated coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102(16):1917–1923. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shmuely H., Passaro D. J., Vaturi M., et al. Association of CagA+ Helicobacter pylori infection with aortic atheroma. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179(1):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S. S., Tondella M. L. C., Bajpai A., et al. Circulating Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA and advanced coronary artery disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2007;118(2):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Ghamdi A. Role of herpes simplex virus-1, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in atherosclerosis. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2012;25(1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malkin J.-E. Epidemiology of genital herpes simplex virus infection in developed countries. Herpes. 2004;11(supplement 1):2A–23A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabricant C. G., Fabricant J., Litrenta M. M., Minick C. R. Virus-induced atherosclerosis. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1978;148(1):335–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Span A. H. M., van Dam-Mieras M. C. E., Mullers W., Endert J., Muller A. D., Bruggeman C. A. The effect of virus infection on the adherence of leukocytes or platelets to endothelial cells. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;21(3):331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1991.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etingin O. R., Hajjar D. P. Evidence for cytokine regulation of cholesterol metabolism in herpesvirus-infected arterial cells by the lipoxygenase pathway. Journal of Lipid Research. 1990;31(2):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Key N. S., Vercellotti G. M., Winkelmann J. C., et al. Infection of vascular endothelial cells with herpes simplex virus enhances tissue factor activity and reduces thrombomodulin expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(18):7095–7099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesonen E., Andsberg E., Grubb A., et al. Elevated infection parameters and infection symptoms predict an acute coronary event. Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 2008;2(6):419–424. doi: 10.1177/1753944708098695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siscovick D. S., Schwartz S. M., Corey L., et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus type 1, and cytomegalovirus and incident myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease death in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2000;102(19):2335–2340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kis Z., Sas K., Gyulai Z., et al. Chronic infections and genetic factors in the development of ischemic stroke. New Microbiologica. 2007;30(3):213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan X., Yang W., Sun X., et al. Association of influenza virus infection and inflammatory cytokines with acute myocardial infarction. Inflammation Research. 2012;61(6):591–598. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorlie P. D., Nieto F. J., Adam E., Folsom A. R., Shahar E., Massing M. A prospective study of cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus 1, and coronary heart disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(13):2027–2032. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mundkur L. A., Rao V. S., Hebbagudi S., et al. Pathogen burden, cytomegalovirus infection and inflammatory markers in the risk of premature coronary artery disease in individuals of Indian origin. Experimental and Clinical Cardiology. 2012;17(2):63–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. The British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantel N., Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begg C. B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. The British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendy A., Vieira E. R., Gasana J. Seropositivity to herpes simplex virus type 2, but not type 1 is associated with premature cardiovascular diseases: a population-based cross-sectional study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(1):18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jafarzadeh A., Nemati M., Tahmasbi M., Ahmadi P., Rezayati M. T., Sayadi A. R. The association between infection burden in Iranian patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Acta Medica Indonesiana. 2011;43(2):105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heltai K., Kis Z., Burian K., et al. Elevated antibody levels against Chlamydia pneumoniae, human HSP60 and mycobacterial HSP65 are independent risk factors in myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173(2):339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vahdat K., Jafari S. M., Pazoki R., Nabipour I. Concurrent increased high sensitivity C-reactive protein and chronic infections are associated with coronary artery disease: a population-based study. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2007;61(3):135–143. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.30748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad A., Zhu J., Halcox J. P. J., Waclawiw M. A., Epstein S. E., Quyyumi A. A. Predisposition to atherosclerosis by infections: role of endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;106(2):184–190. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000021125.83697.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georges J.-L., Rupprecht H. J., Blankenberg S., et al. Impact of pathogen burden in patients with coronary artery disease in relation to systemic inflammation and variation in genes encoding cytokines. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;92(5):515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindberg G., Råstam L., Lundblad A., Sorlie P. D., Folsom A. R. The association between serum sialic acid and asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis is not related to antibodies to herpes type viruses or Chlamydia pneumoniae. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;26(6):1386–1391. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.6.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J., Quyyumi A. A., Norman J. E., et al. Effects of total pathogen burden on coronary artery disease risk and C-reactive protein levels. American Journal of Cardiology. 2000;85(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adam E., Melnick J. L., Probtsfield J. L., et al. High levels of cytomegalovirus antibody in patients requiring vascular surgery for atherosclerosis. The Lancet. 1987;2(8554):291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90888-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan A. Z., Ye X. L., Wang Y. C. Exploration of the association between herpes simplex virus infection and coronary heart disease. International Medicine & Health Guidance News. 2005;11(24):83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan J. H., Zuo L. Investagation of the correlation between herpes simplex virus infection and heart attack. Journal of Guiyang Medical College. 1999;24(3):227–228. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu D. D., He Z. Y., Li J. S. Relation of herpes simplex virus infection to acute myocardial infarction and thromboxane B2, 6-Keto-prostaglandin-F1α and P-selection of patients with myocardial infarction. Chinese Circulation Journal. 2004;19(4):262–265. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X., Tang Q., Xu L. Herpes simplex virus 2 infects human endothelial ECV304 cells and induces cell apoptosis synergistically with ox-LDL. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2014;39(6):909–917. doi: 10.2131/jts.39.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Etingin O. R., Silverstein R. L., Hajjar D. P. Identification of a monocyte receptor on herpesvirus-infected endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(16):7200–7203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chirathaworn C., Pongpanich A., Poovorawan Y. Herpes simplex virus 1 induced LOX-1 expression in an endothelial cell line, ECV 304. Viral Immunology. 2004;17(2):308–314. doi: 10.1089/0882824041310531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hajjar D. P., Pomerantz K. B., Falcone D. J., Weksler B. B., Grant A. J. Herpes simplex virus infection in human arterial cells. Implications in arteriosclerosis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1987;80(5):1317–1321. doi: 10.1172/jci113208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Key N. S., Bach R. R., Vercellotti G. M., Moldow C. F. Herpes simplex virus type I does not require productive infection to induce tissue factor in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Laboratory Investigation. 1993;68(6):645–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benditt E. P., Barrett T., McDougall J. K. Viruses in the etiology of atherosclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1983;80(20):6386–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.20.6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu B., Viira E., Tucker W., Fong I. W. Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus in atherosclerosis of the carotid artery. Circulation. 1997;96(7):2144–2148. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi Y., Tokunaga O. Herpesvirus (HSV-1, EBV and CMV) infections in atherosclerotic compared with non-atherosclerotic aortic tissue. Pathology International. 2002;52(1):31–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotronias D., Kapranos N. Herpes simplex virus as a determinant risk factor for coronary artery atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. In Vivo. 2005;19(2):351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albert M. A., Ravenell J., Glynn R. J., Khera A., Halevy N., de Lemos J. A. Cardiovascular risk indicators and perceived race/ethnic discrimination in the Dallas Heart Study. American Heart Journal. 2008;156(6):1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller M., van der Schouw Y. T., Thijssen J. H. H., Grobbee D. E. Endogenous sex hormones and cardiovascular disease in men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2003;88(11):5076–5086. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This supplementary material consisted of one table (Table S1) and two figures (Figure S1 and Figure S2). Table S1 showed the ORs and 95% CI of sensitivity analysis concerning HSV-1 and HSV-2. It was no significant difference detected on the pooled OR which was estimated by omitting one study at a time. Figure S1 was Begg's funnel plots concerning HSV-1, and Figure S2 concerning HSV-2. The shape of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in the overall meta-analysis.