Abstract

Objectives

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is recognised as a reliable long-term predictor of adverse health outcomes. Elevated prevalence rates of MetS and chronic lifestyle diseases have been documented in different indigenous groups. We aimed to evaluate the prevalence of MetS and diabetes mellitus in relation to ethnicity in Northern Norway. In addition, we discussed different cut-off values for waist circumference (WC) and what impact this has on the prevalence of MetS.

Materials and methods

SAMINOR is a population-based study of health and living conditions in areas home to Sami and non-Sami populations. The survey was carried out in 2003–2004. All eligible residents in specific age groups were invited. In total, 16 538 males and females aged 36–79 years participated and gave informed consent for medical research.

Results

This study involved a total of 7822 female and 7290 male participants. Sami affiliation was reported by 5141 participants (34%). The prevalence of MetS was high in both ethnic groups independent of which WC cut-off value was used. No ethnic differences in prevalence of diabetes mellitus were demonstrated. However, ethnicity appeared to affect diabetes treatment, which was more prevalent among Sami than non-Sami women.

Conclusions

In this study, there was no ethnic difference in diabetes prevalence, but ethnicity appeared to affect diabetes treatment. Tablet treatment was more commonly in use among Sami women than among non-Sami women. We demonstrated a high share of negative metabolic components. These metabolic components have important health implications. Therefore, determining preventive initiatives is important in the primary and specialist healthcare system. These initiatives must be made culture and linguistic specific, in order to reduce differences and improve health status in the whole population.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The SAMINOR study is the first survey to report on the prevalence of diabetes and metabolic syndrome (MetS) in a large geographic area of North Norway including both the indigenous and non-indigenous population.

The large sample size allowed for detailed analysis of diabetes and MetS in Sami and non-Sami populations of rural North Norway.

The survey has a relatively high response rate.

Categorising people based on ethnicity is a contentious practice. Different studies use different criteria of ethnicity, which makes it difficult to compare results.

Cross-sectional data cannot assess the effect of lifestyle on the incidence of MetS, and longitudinal cohort studies are, therefore, needed.

Introduction

Chronic disease has become a global problem and a burden on healthcare services, reaching epidemic proportions. In Norway, as well as internationally, the great majority of patients in healthcare systems are living with chronic disease.1 2 Cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the most common causes of hospitalisation and premature death.3 Unfavourable health factors such as obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and hypertension are known to elevate risks of developing CVD and T2DM. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) indicates a cluster of these risk factors.4 5 MetS is generally recognised as a reliable long-term predictor of adverse health outcomes.6 Further, MetS has been recognised as a growing, global public health problem.7 In addition, several studies demonstrate MetS to be associated with elevated cancer risk.8 9

Information on the prevalence of chronic disease in various ethnicities of North Norway remains sparse. The Sami, Kven and Norwegian ethnic groups have inhabited the region for centuries; the Norwegian government acknowledges the Sami people as the indigenous people of Norway. The Norwegian health authorities have little systematic knowledge about the health status and living conditions among the Sami. National health and medical registers contribute to comprehensive information and knowledge about health-related lifestyle and disease prevalence. However, by law, information about ethnic background is not permitted to be documented in these registers nor in patients' medical records. Therefore, no reliable or updated demographic records on the Sami exist that can be used for health research purposes.

Several epidemiological studies have documented elevated prevalence rates for chronic lifestyle diseases in a number of different minority groups.5 10 11 Although such disorders have emerged quite recently in indigenous populations—mainly due to changes in lifestyle and diet—they are, however, prevalent in several such populations.12 13 Publications from the SAMINOR study of North Norway demonstrate that the prevalence of obesity was high in the survey population, especially among Sami women.14 15

In order to evaluate the health of indigenous and non-indigenous populations of Norway (inhabiting the same geographic area) it was necessary to conduct an epidemiological survey. The present study aims to evaluate the prevalence of MetS and diabetes mellitus in Sami and non-Sami populations residing in selected areas of North Norway. In addition, we will discuss different cut-off values for waist circumference (WC) and what impact this has on the prevalence of MetS.

Methods

The SAMINOR study

The cross-sectional data are derived from the SAMINOR study from 2003 to 2004 (SAMINOR 1). The SAMINOR study was conducted by the Centre for Sami Health Research, Department of Community Medicine, UiT—the Arctic University of Norway, in collaboration with the National Screening Program for Cardiovascular Diseases. The survey is described in detail elsewhere.16

The study sample

All eligible residents aged 30 and 36–79 years, registered in the Central Population Register in 24 selected municipalities were invited regardless of ethnic background (n=27 987). Owing to a low response rate among those aged 30 years, our analyses were restricted to the age interval 36–79 years (n=27 151). In total, 16 538 males and females aged 36–79 years participated and gave informed consent for medical research. The response rate was 61%. Data were obtained from physical tests and blood samples. Information on ethnicity and the different diagnostic tools for MetS were available for 15 112 participants.

Questionnaire design

An invitation was mailed several weeks before the survey arrived at the municipality. The invitation contained information about the time and place of screening, together with a five-page questionnaire. Those who agreed to attend the screening returned the questionnaire to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. These participants later received an invitation to the clinical examination. After the consultation, the participants were asked to complete a new questionnaire. Information regarding ethnicity, disease and lifestyle was collected using these two self-administrated questionnaires. The questionnaires were translated into the three main Sami languages: Northern, Lule and South Sami. However, as only 1.6% of the participants chose to use the Sami version of the questionnaire, any language problems are probably of little importance in this study. Ethnicity was measured using the following questions: ‘What language(s) do/did you, your parents and your grandparents use at home?’ The questions were to be answered separately for each relative. The available responses were: ‘Norwegian’, ‘Sami’, ‘Kven’ and ‘Other’. Multiple answers were allowed. Providing the same response options we also asked: ‘What is your, your father's and your mother's ethnic background?’ The respondents also reported whether they considered themselves to be Norwegian, Sami, Kven or other (self-perceived ethnicity). We refer to Lund et al16 for a full description of the ethnicity and language questions. Based on these variables, we generated two categories of ethnicity: ‘Sami’ and ‘Non-Sami’. Participants reporting at least one Sami identity mark (Sami language spoken by the respondent or at least one parent or grandparent, or Sami ethnic background or self-perceived Sami ethnicity) were placed in the category ‘Sami’. The remainder comprised the ‘Non-Sami’ participants.

Screening

Owing to the large size of the study sample, participants were examined at different times of day. This meant that it was not possible to ask participants to fast prior to arrival. Non-fasting blood samples were obtained at the research station. Blood samples were drawn by venopuncture at normal venous pressure, in a sitting position. Serum was separated at the station within 1.5 h. Serum was sent by overnight mail to laboratories in Oslo and Tromsø. The laboratory analyses are described in detail elsewhere.17

Body mass index (BMI) was based on measurements of weight and height, and expressed as body weight in kilograms/(body height in metres)2. BMI categories were defined according to guidelines from the WHO; ‘underweight’ corresponding to a BMI<18.5 kg/m², ‘standard weight’ in the range 18.5–24.9 kg/m², ‘overweight’ in the range 25–29.9 kg/m² and ‘obese’ ≥30 kg/m².18

WC, which is used to identify abdominal obesity, was measured (to the nearest centimetre) at the umbilicus, with the participant standing erect. Two different WC cut-off values were applied to define abdominal obesity to enable the comparison of how the corresponding values influenced the subsequently calculated prevalence of MetS. The US National Institute of Health (NIH) Clinical Practice Guidelines defines central/abdominal obesity as WC≥102 cm in males and WC≥88 cm in females.19 In addition, abnormal WC for Europid males is ≥94 cm and for females it is ≥80 cm. These figures are based on cross-sectional data from Europids and were included in the analyses.18 20

Trained personnel measured blood pressure (BP), using a Dinamap—R automatic device. Measurements were initiated after participants had been seated for 2 min with their arms resting on a table. BP was measured three times, at 1 min intervals. The mean value of the second and third reading was used in the analysis.

Diabetes mellitus

Because all blood samples in the SAMINOR study were non-fasting, we used random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L, in addition to self-reported diabetes and information about antidiabetic medication from a questionnaire, to define diabetes mellitus. The question on diabetes mellitus was: ‘Do you have or have you had diabetes?’ The available responses were ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Missing values were classified as ‘no’. In the absence of oral glucose tolerance tests, we used random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L as a substitute for elevated oral glucose tolerance test.

Metabolic syndrome

Several attempts have been made at developing diagnostic criteria for the definition of MetS.21–23 In 2004, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the WHO and the National Cholesterol Education Program Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III), produced a consensus statement on the definition of MetS.24 The latter definition requires central obesity and cut-off points to be specified according to gender and ethnicity. Central obesity is most commonly measured by WC; cut-off values are based on cross-sectional studies conducted in Europe, the USA and Asia.18 19 20 25 The diagnostic tools are intended for clinical and research purposes. The definition of MetS used in this article adheres to the IDF MetS worldwide definition24—central obesity plus any two of four additional factors: elevated triglyceride level >1.7 mmol/L, reduced HDL-cholesterol <1.03 mmol/L in males and <1.29 mmol/L in females, elevated BP (systolic BP≥130 or diastolic BP≥85 mm Hg) and elevated fasting plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were stratified by gender. Sample characteristics were presented separately by gender and ethnicity as mean values for continuous variables with corresponding 95% CIs. Analyses of variance were used for tests of ethnic differences (table 1). Differences according to diabetes mellitus and MetS prevalence were tested by χ2 tests (tables 2 and 3). MetS prevalence was also stratified by age (table 3). Logistic regression analyses were used to test for age influence on MetS with age as a continuous variable (table 3).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by gender and ethnic group (N=15 112)

| Men | Sami (N=2559) | Non-Sami (N=4731) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | 55.0 (54.8 to 55.1) | 54.8 (54.7 to 54.9) | 0.584 |

| Height (cm) | 170.0 (170.0 to 170.2) | 175.7 (175.6 to 175.8) | <0.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.6 (80.4 to 80.7) | 85.1 (85.0 to 85.3) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 (27.7 to 27.9) | 27.5 (27.5 to 27.6) | 0.009 |

| WC (cm) | 93.2 (93.0 to 93.3) | 95.0 (94.9 to 95.2) | <0.0001 |

| Non-fasting glucose (mmol/L | 5.8 (5.8 to 5.8) | 5.8 (5.7 to 5.8) | 0.313 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.27 (1.26 to 1.28) | 1.25 (1.25 to 1.26) | 0.115 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.87 (3.86 to 3.89) | 3.80 (3.79 to 3.81) | 0.004 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.98 (5.96 to 5.99) | 5.90 (5.90 to 5.90) | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.86 (1.85 to 1.88) | 1.86 (1.85 to 1.88) | 0.970 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 135 (135 to 135) | 134 (134 to 134) | 0.168 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 78 (78 to 78) | 78 (78 to 78) | 0.182 |

| Women | Sami (N=2581) Mean (95% CI) |

Non-Sami (N=5241) Mean (95% CI) |

p Value |

| Age (years) | 54.2 (54.1 to 54.4) | 54.5 (54.4 to 54.6) | 0.277 |

| Height (cm) | 157.3 (157.2 to 157.4) | 162.6 (162.6 to 162.7) | <0.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.7 (69.6 to 69.9) | 72.1 (71.9 to 72.2) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 (28.1 to 28.3) | 27.3 (27.2 to 27.3) | <0.0001 |

| WC (cm) | 86.0 (85.9 to 86.2) | 85.5 (85.4 to 85.6) | 0.053 |

| Non-fasting glucose (mmol/L | 5.66 (5.63 to 5.68) | 5.57 (5.55 to 5.58) | 0.018 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.45 (1.44 to 1.45) | 1.49 (1.49 to 1.50) | <0.0001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.82 (3.81 to 3.83) | 3.81 (3.80 to 3.82) | 0.707 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.98 (5.96 to 5.99) | 5.99 (5.98 to 6.00) | 0.617 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.54(1.56 to 1.59) | 1.53 (1.52 to 1.54) | 0.044 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 130 (129 to 130) | 130 (130 to 131) | 0.125 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 72 (72 to 72) | 73 (73 to 73) | 0.008 |

*Test of differences, ANOVA, for Sami versus non-Sami.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; WC, waist circumference.

Table 2.

Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and diabetes treatment in the SAMINOR study (N=15 112)

| Sami (N=2559) | Non-Sami (N=4731) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | n (%) | n (%) | p Value |

| Diabetes prevalence | 132 (5.2) | 212 (4.5) | 0.19* |

| Insulin treatment | 13 (0.5) | 31 (0.7) | |

| Tablet treatment | 45 (1.8) | 87 (1.8) | |

| Insulin and tablet treatment | 25 (1.0) | 21 (0.4) | |

| Non-treatment | 49 (1.9) | 73 (1.5) | |

| Non-diabetes | 2427 (33.3) | 4519 (95.5) | 0.05† |

| Sami (N=2581) | Non-Sami (N=5241) | ||

| Women | n (%) | n (%) | p Value |

| Diabetes prevalence | 129 (5.0) | 220 (4.2) | 0.11* |

| Insulin treatment | 13 (0.5) | 29 (0.6) | |

| Tablet treatment | 61 (2.4) | 71 (1.6) | |

| Insulin and tablet treatment | 20 (0.8) | 38 (0.7) | |

| Non-treatment | 35 (1.4) | 82 (1.6) | |

| Non-diabetes | 2452 (95.0) | 5021 (95.8) | 0.025† |

*χ2 Test for differences in diabetes prevalence among Sami versus non-Sami.

†χ2 Test for differences in treatment level among Sami versus non-Sami.

Table 3.

Prevalence of MetS among Sami and non-Sami, by age groups and gender (N=15 112)

| Men (years) | European cut-off of WC |

NIH cut-off of WC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sami (N=650) n (%) |

Non-Sami (N=917) n (%) |

p Value* | Sami (N=315) n (%) |

Non-Sami (N=728) n (%) |

p Value* | |

| 36–49 | 194 (22.3) | 429 (26.0) | 0.038 | 89 (10.2) | 203 (12.3) | 0.118 |

| 50–59 | 229 (27.2) | 440 (29.7) | 0.202 | 115 (13.7) | 238 (16.1) | 0.121 |

| 60–79 | 227 (26.9) | 489 (30.6) | 0.055 | 111 (13.1) | 287 (18.0) | 0.002 |

| p Value† | 0.029 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | ||

| Women (years) | Sami (N=790) n (%) |

Non-Sami (N=1521) n (%) |

Sami (N=588) n (%) |

Non-Sami (N=1091) n (%) |

||

| 36–49 | 232 (24.4) | 369 (19.1) | 0.006 | 161 (16.2) | 263 (13.6) | 0.056 |

| 50–59 | 248 (31.5) | 455 (29.4) | 0.291 | 177 (22.5) | 309 (20.0) | 0.155 |

| 60–79 | 310 (38.7) | 697 (39.6) | 0.641 | 250 (31.2) | 519 (29.5) | 0.393 |

| p Value† | 0.004 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

*χ2 tests for differences in MetS prevalence of Sami versus non-Sami.

†Age effect tested by logistic regression with age as a continuous variable.

MetS, metabolic syndrome; NIH, National Institute of Health; WC, waist circumference.

We used the SAS statistical software package, V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

The current analysis involved a total of 7822 female and 7290 male participants. Sami affiliation was reported by 5141 participants (34%). Table 1 shows gender-specific and ethnicity-specific characteristics at enrolment in the study.

The mean BMI was greater in Sami males, whereas the mean WC was greater in non-Sami males. Sami females, however, showed significantly greater values for mean BMI, WC and lipids.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of diabetes in Sami and non-Sami participants.

No differences in prevalence of diabetes mellitus was demonstrated between ethnic groups; however, ethnicity appeared to affect diabetes treatment. Particularly, tablet treatment was more commonly used among Sami women than among non-Sami women. However, a combination of tablet and insulin treatment was more frequently in use among Sami men than among non-Sami men.

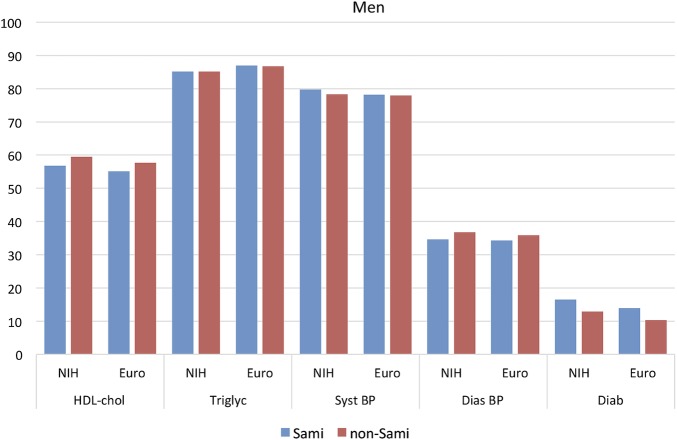

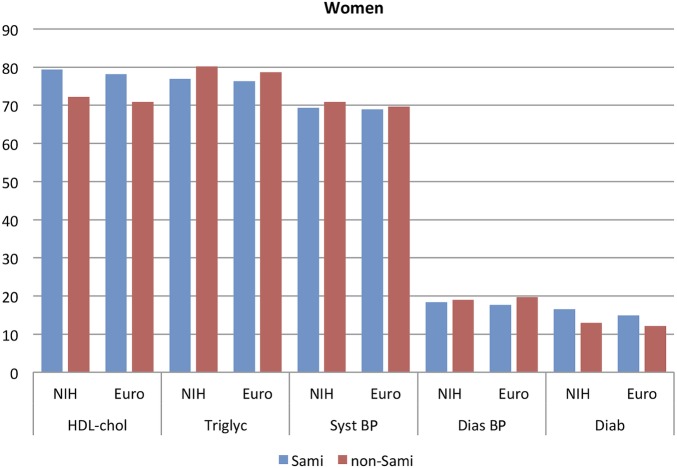

The prevalence of the various diagnostic tools for MetS is presented in figures 1 (males) and 2 (females).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of different risk markers in participants with MetS. Men, N=2008 Euro and N=1043 NIH. BP, blood pressure; Euro, European; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NIH, National Institute of Health.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of different risk markers in participants with MetS. Women, N=2311 Euro and N=1679 NIH. BP, blood pressure; Euro, European; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NIH, National Institute of Health.

The most prevalent risk marker for MetS (aside from central obesity) was the presence of elevated systolic BP and high triglyceride levels, independent of gender and ethnicity.

Table 3 presents the prevalence of MetS according to WC cut-off points based on European and NIH values.

In each age bracket, the results are stratified according to ethnicity (Sami and non-Sami). Based on the European WC cut-off points, prevalence of MetS was higher in non-Sami participants in the age bracket 36–49 years. However, when applying the NIH WC cut-off point, a significantly lower prevalence was found for Sami males in the top age group.

Non-Sami males showed a higher overall prevalence of MetS (in comparison with Sami males) for both WC cut-off values. In females, ethnicity was not significant overall; however, when stratified by age, a significantly higher prevalence of MetS in the younger Sami females (in comparison with non-Sami females) was found—when applying the European WC cut-off value. The prevalence of MetS increased with age regardless of gender and ethnicity. The proportion of women with all four risk markers was almost twice as large within the Sami population (in comparison with non-Sami females) for both WC cut-off values (not shown). For males, ethnicity appeared not to affect the number of risk markers found.

Discussion

The prevalence of MetS was high in both ethnic groups. No difference in prevalence of diabetes mellitus was demonstrated between ethnic groups. It was more common to give treatment for diabetes to Sami men and women than providing it to the non-Sami population. The two different WC cut-off values greatly influenced the measured prevalence of MetS. The present study demonstrates that ethnicity is a significant factor for MetS in participants belonging to the lowest age bracket.

The two different WC cut-off values greatly influenced the measured prevalence of MetS. The present study demonstrates that ethnicity is a significant factor for MetS in participants belonging to the lowest age bracket. In the case of males aged between 36 and 49 years, MetS is less prevalent in the Sami population (in comparison with non-Sami). For females in the same age bracket, however, MetS is more prevalent in the Sami population. When the NIH cut-offs were used, we found that—in the highest age bracket—the non-Sami males showed significantly higher prevalence of MetS in comparison with Sami males. The prevalence of MetS increased significantly by age in both ethnic groups, regardless of which WC cut-off values were used.

In general, overweight and obesity were common among the participants in the SAMINOR study. From earlier publications based on the SAMINOR study, central obesity has been shown to be more common in Sami females.15 14 General obesity in Sami females has also been discussed by Njolstad et al.26 However, obesity rates were high in non-Sami females as well.14 For males, central obesity occurred more frequently in the non-Sami population relative to the Sami population.14 15

MetS has several different definitions, making it difficult to directly compare and contrast prevalence found in different surveys. WC is the most significant measurement of central obesity and fat distribution, according to the IDF.27 The group that produced the consensus statement on the definition of MetS in 2004 recommended that gender and ethnicity should be the basis for classification of cut-off points.24 The existing values are based on cross-sectional population survey data from the respective countries. How to define the WC cut-off point in the various indigenous populations has not yet been established; however, an immediate response would be to perform cross-sectional population surveys within indigenous societies. In our study, two different cut-off points were used in order to facilitate comparison. The European cut-off values doubled the prevalence of MetS in males and increased prevalence by more than 40% in females (compared with values found when applying NIH WC cut-off values). This was the case in both ethnic groups. But the question of what the WC values should be in terms of optimal prediction of prospective disease in the SAMINOR sample remains unanswered. A follow-up study could provide better answers to questions regarding disease development.

Irrespective of cut-off values, elevated BP was the most frequent MetS component present in obese participants. These findings were also demonstrated in a collaborative analysis of 10 large cohort studies in Europe.28 In the 10 studies included, obesity coincided with hypertension in up to 85% of cases.

The presence of MetS, as well as its individual components, however, shows considerable variance between populations. Several studies of MetS have been performed in circumpolar areas, such as in indigenous peoples of Alaska, Canada and Greenland.29–31 American Indians and Aboriginal Canadians represent populations in which MetS, obesity and T2DM are becoming more prevalent.13 29 MetS also frequently occurs in Greenland's Inuit population.31 A health survey in Greenland showed that central adiposity and obesity were more prevalent in the Inuit population when compared with the corresponding Danish population, but was not associated with the same degree of metabolic disturbance as in the general Danish population.32 Yet, it is debatable which factors in the cluster of MetS are the most significant in the development of chronic lifestyle diseases.

There is a significant relation between T2DM and MetS; the syndrome itself is not a disease, but consists of a cluster of factors that increase the risk for developing diseases. Thus, we prefer to include diabetes in this article to demonstrate the link between the health indicator MetS and diabetes mellitus.24 In the SAMINOR study, diabetes mellitus was identified using a questionnaire, in addition to measured random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L in participants who did not report diabetes mellitus. As the study had a large number of participants, up to 140 per day, conducting 2 h plasma glucose tolerance tests was considered unfeasible. The portable glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) instruments available in 2003–2004 were inadequate for conducting HbA1C measurements at rural research stations. In addition, the survey was performed in provincial areas at long distances from the medical laboratory.

Our analyses do not differentiate between type 1 diabetes mellitus and T2DM due to insufficient information provided by the questionnaire. However, 8 of 10 diabetes cases in Norway are T2DM.33 Also, globally, around 80% of diabetes cases are T2DM,34–36 giving a prevalence rate of 8.3%. This figure is expected to increase due to lifestyle changes.35 Diabetes prevalence in our study was between 4% and 5%, which is a lower rate than the prevalence rate found in the urban population residing in 2007–2008 in the city of Tromsø (8.5%).37 This study encompassed participants aged between 30 and 87 years, with a mean age of 61 years. However, in the Tromsø study, fasting plasma glucose, 2 h plasma glucose and HbA1c was measured. It is therefore likely that the present study under-reports the diabetes prevalence by as much as up to 50%. The significance of treatment differences between ethnic groups has not been reported earlier and is difficult to explain. These findings will therefore be addressed in future research.

Strengths

Our study is the first survey to report on the prevalence of diabetes and MetS in a large geographic area of North Norway including both the indigenous and the non-indigenous population. The large sample size allowed for detailed analysis of diabetes and MetS in Sami and non-Sami populations of rural North Norway; it also reduces the influence of random errors, which cannot fully be controlled for. The survey had a relatively high response rate.

Unquestionably, one of the strengths of the study was that clinical data—such as central obesity (on which MetS relies)—were collected by direct measurement and conducted by trained personnel, providing reliable estimates of obesity prevalence in the participating cohort.

Limitations

The cross-sectional study design is suitable for the examination of associations in order to generate hypotheses that may be explored in longitudinal studies. Conversely, however, the design prevents the establishment of causality. Owing to the nature of the design, people with severe disease may be missed because they are either diseased at home or in long-term hospitalisation, or have died in the time since the sample list was prepared (ie, selection bias). The SAMINOR study has used questionnaires to survey self-reported diseases. This approach cannot detect people with undiagnosed symptoms and is limited by recall bias. In Norway, it is estimated that between 9000 and 120 000 people have diabetes and nearly as many have undiagnosed disease.38

Categorising people based on ethnicity is a contentious practice. Different studies use different criteria of ethnic categorisation, which makes it difficult to compare results. Our definition of the Sami group is rather weak. This may have influenced our results. Since there are no national records with information on ethnic background, it is impossible to know if the response rates among Sami and non-Sami are different. We are therefore unable to assess whether differences in participation have influenced the observed disease burden.

In summary, cross-sectional studies may be used in the measurement of the burden of disease in a population. However, cross-sectional data cannot assess the effect of lifestyle on the incidence of MetS, and longitudinal cohort studies are therefore needed.

Conclusion

Without question, the prevalence rates for several negative health factors were high in the Sami and non-Sami populations. Overweight and obesity were common, especially in the case of Sami females. No difference in prevalence of diabetes mellitus was demonstrated between the ethnic groups. However, ethnicity appeared to affect diabetes treatment and was significantly more frequently in use among Sami women than among non-Sami women. However, the prevalence of MetS was generally high among participants in the SAMINOR study, with the highest prevalence for the European cut-off values. The syndrome has important health implications, but a cross-sectional study cannot be used to validate the best ethnicity-specific values for WC used in the definition of MetS and more data on this issue must be obtained. In addition, determining preventive initiatives is important in the primary and specialist healthcare system. These initiatives must be made culture and linguistic specific, in order to reduce differences and improve health status in the whole population.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the participants of the SAMINOR study, without whom the research would have been impossible. They would also like to thank the staff at the Department of Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital of North Norway, for technical assistance and careful evaluation of blood samples.

Footnotes

Contributors: The idea behind the study was conceived by ARB. Both authors participated in the study concept and design. ARB drafted the manuscript. Both authors performed the analyses of the tables and figures. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Funding for this project was provided by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Approval was granted by the Regional Board of Research Ethics in Northern Norway and by the Board's Sami Consultant (2002/1525-2). The survey is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The National Data Protection Authority (Datatilsynet) approved the use of personal information.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing ann.ragnhild.broderstad@uit.no.

References

- 1.Banatvala N, Donaldson L. Chronic diseases in developing countries. Lancet 2007;370:2076–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61877-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale AC, Nilsen TI, Vatten L et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of fatal ischaemic heart disease by gender: 18 years follow-up of 74,914 individuals in the HUNT 1 Study. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2924–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parajuli R, Bjerkaas E, Tverdal A et al. The increased risk of colon cancer due to cigarette smoking may be greater in women than men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013;22:862–71. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 2004;109:433–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons RK, Alberti KG, Gale EA et al. The metabolic syndrome: useful concept or clinical tool? Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Diabetologia 2010;53:600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: a summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1769–78. 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. On treating metabolic syndrome: emphasise lifestyle change. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:415 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70055-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishino K, Mutoh M, Totsuka Y et al. Metabolic syndrome: a novel high-risk state for colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett 2013;334:56–61. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo A, Autelitano M, Bisanti L. Metabolic syndrome and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:293–7. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence in worldwide populations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2004;33:351–75, table of contents 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyer BB, Mohatt GV, Plaetke R et al. Metabolic syndrome in Yup'ik Eskimos: the Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2535–40. 10.1038/oby.2007.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Young TK, Zinman B et al. Lifestyle variables, non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and the metabolic syndrome in an Aboriginal Canadian population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:500–8. 10.1038/oby.2006.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher C, Ferucci ED, Lanier AP et al. Metabolic syndrome: prevalence among American Indian and Alaska native people living in the southwestern United States and in Alaska. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2008;6:267–73. 10.1089/met.2008.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nystad T, Melhus M, Brustad M et al. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of general and central obesity among the Sami and Norwegian populations: the SAMINOR study. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:17–24. 10.1177/1403494809354791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broderstad AR, Melhus M, Lund E. Iron status in a multiethnic population (age 36-80 yr) in northern Norway: the SAMINOR study. Eur J Haematol 2007;79:447–54. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00929.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lund E, Melhus M, Hansen KL et al. Population based study of health and living conditions in areas with both Sami and Norwegian populations—the SAMINOR study. Int J Circumpolar Health 2007;66:113–28. 10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nystod T, Utsi E, Selmer R et al. Distribution of apoB/apoA-1 ratio and blood lipids in Sami, Kven and Norwegian populations: the SAMINOR study. Int J Circumpolar Health 2008;67:67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO technical Report Series 894. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000:1997 Report by the Secretari. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB130/B130_9-en.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen I, Peter T, Katzmarzyk PT et al. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2074–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ 1995;311:158–61. 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balkau B, Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med 1999;16:442–3. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleeman JI. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome—a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 2006;23:469–80. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin WY, Lee LT, Chen CY et al. Optimal cut-off values for obesity: using simple anthropometric indices to predict cardiovascular risk factors in Taiwan. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:1232–8. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Njolstad I, Arnesen E, Lund-Larsen PG. Cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus in different ethnic groups: the Finnmark study. Epidemiology 1998;9:550–6. 10.1097/00001648-199809000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2004;53:2087–94. 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Nuotio ML, Slagter SN et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolically healthy obesity in Europe: a collaborative analysis of ten large cohort studies. BMC Endocr Disord 2014;14:9 10.1186/1472-6823-14-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley SH, Harris SB, Mamakeesick M et al. Metabolic syndrome and its components as predictors of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in an Aboriginal community. CMAJ 2009;180:617–24. 10.1503/cmaj.080972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell M, de Simone G, Resnick HE et al. The metabolic syndrome in American Indians: the strong heart study. J Cardiometab Syndr 2007;2:283–7. 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorgensen ME, Bjerregaard P, Gyntelberg F et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among the Inuit in Greenland. A comparison between two proposed definitions. Diabet Med 2004;21:1237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorgensen ME. Obesity and metabolic correlates among the Inuit and a general Danish population. Int J Circumpolar Health 2004;63(Suppl 2):77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folkehelseinstituttet. Forekomst av diabetes—faktaark med helsestatistikk. http://www.fhi.no/artikler/?id=70814 Folkehelseinstituttet 2015.

- 34.Velho G, Froguel P, Mann J et al. Type 2 diabetes. In: Ekoe J, Zimmet P, Williams R, eds. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2001:133–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Federation ID. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th edition [internet] 2013. http://idf.org/diabetesatlas (accessed 4 May 2013).

- 36.Gao XH, Winsey S, Li G et al. HLA-DR and DQ polymorphisms in bullous pemphigoid from northern China. Clin Exp Dermatol 2002;27:319–21. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchinson MS, Joakimsen RM, Njolstad I et al. Effects of age and sex on estimated diabetes prevalence using different diagnostic criteria: the Tromso OGTT study. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:613475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stene LC, Midthjell K, Jenum AK et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegrforen 2004;124:1511–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]