Abstract

Objective

To explore conflicts of interest (COI) and their reporting in systematic reviews of psychological therapies, and to evaluate spin in the conclusions of the reviews.

Methods

MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases were searched for systematic reviews published between 2010 and 2013 that assessed effects of psychological therapies for anxiety, depressive or personality disorders, and included at least one randomised controlled trial. Required COI disclosure by journal, disclosed COI by review authors, and the inclusion of own primary studies by review authors were extracted. Researcher allegiance, that is, that researchers concluded favourably about the interventions they have studied, as well as spin, that is, differences between results and conclusions of the reviews, were rated by 2 independent raters.

Results

936 references were retrieved, 95 reviews fulfilled eligibility criteria. 59 compared psychological therapies with other forms of psychological therapies, and 36 psychological therapies with pharmacological interventions. Financial, non-financial, and personal COI were disclosed in 22, 4 and 1 review, respectively. 2 of 86 own primary studies of review authors included in 34 reviews were disclosed by review authors. In 15 of the reviews, authors showed an allegiance effect to the evaluated psychological therapy that was never disclosed. Spin in review conclusions was found in 27 of 95 reviews. Reviews with a conclusion in favour of psychological therapies (vs pharmacological interventions) were at high risk for a spin in conclusions (OR=8.31 (1.41 to 49.05)). Spin was related in trend to the inclusion of own primary studies in the systematic review (OR=2.08 (CI 0.83 to 5.18) p=0.11) and researcher allegiance (OR=2.63 (0.84 to 8.16) p=0.16).

Conclusions

Non-financial COI, especially the inclusion of own primary studies into reviews and researcher allegiance, are frequently seen in systematic reviews of psychological therapies and need more transparency and better management.

Keywords: bias, psychotherapy, conflict of interest, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study addresses a widely neglected research topic, that is, spin introduced by non-financial conflicts of interest (COI), for example, the researcher's allegiance to a specific therapy, in reviews on psychotherapy studies.

Although authors of reviews of psychological therapies frequently show COI (which mainly are not declared), the relationship to spin in review conclusions is less clear and has to be interpreted with caution.

We decided to use the term ‘spin’ instead of ‘bias’, although we cannot make claims about the nature of the influence which might be mere bias or more intentional spin.

The selection of studies up to 2013 does not reflect possible changes in COI declarations in recent years.

Introduction

Conflicts of interest (COI) are defined as a set of circumstances that creates a risk that a professional judgement or action regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest.1 2 Research on COI has so far mainly focused on financial COI such as close financial relationships between researchers or medical doctors and pharmaceutical companies, or the financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies.3–7 Such research has shown that studies funded by pharmaceutical companies more often yield results or conclusions in favour of the sponsoring company as compared to non-industry-funded trials;8 9 that close relationships of researchers to pharmaceutical companies are linked to biased assessments of drug safety and efficacy;10 11 that positive trials are more likely to be published than trials unfavourable to sponsors;12 and that COI are under-reported in meta-analyses of pharmacological treatments.13 14

The influence of non-financial COI, however, on the framing of research questions, the data analysis and interpretation of results, or the decision which results are being published, has been much less extensively studied.15 With respect to outcome research of psychological therapies, researcher allegiance constitutes an important non-financial COI. Allegiance covers the belief of a researcher in the superiority of a treatment.16 17 Allegiance may be due to a special training in one specific psychological therapy, the involvement in previous efficacy research about this psychological therapy or the involvement in development of aetiological models via basic research.18–20 Empirical studies showed a strong impact of researcher allegiance on outcome in psychotherapy studies: a recent meta-analysis showed a robust and moderate allegiance outcome association (r=0.26),21 and such an association is also present in equally effective treatments.22 Taking allegiance into account for the explanation of effect differences between two active treatments studies with balanced allegiance for two different treatments show no difference in the effectiveness.23

Since nothing is known about the extent and nature of non-financial COI in systematic reviews of psychological therapies, the aim of this study was to investigate how often non-financial COI are present and disclosed in systematic reviews of psychological therapies, and to analyse whether these COI increase the risk of spin in the conclusions of the reviews.

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria of systematic reviews

We searched the MEDLINE and PsycINFO data bases for systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCT) on psychological therapies. Reviews were selected if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) inclusion of psychological therapies to treat patients with anxiety disorders, personality disorders and/or major depressive disorders in adults, (2) active control groups with either other forms of psychological therapy or pharmacological interventions, (3) inclusion of at least one randomised study and (4) English language. Searches were last run on 3 February 2014, covering the publication period of January 2010–December 2013. For exact MEDLINE and PsycINFO search strategies, refer online supplementary tables S1 and S2.

bmjopen-2015-010606supp.pdf (334.7KB, pdf)

Screening and inclusion of systematic reviews and primary studies

Retrieved references were initially screened for inclusion by title and abstract by two independent researchers. In a second step, full texts of relevant reviews were retrieved and assessed for inclusion by two independent researchers. These reviews were used to rate COI and their disclosure.

Primary studies included in these reviews were identified from the reference lists of the systematic reviews and retrieved if one of the coauthors of the review was an author of the respective primary study. These primary studies were then used to rate researcher allegiance.

Assessment of disclosed and undisclosed COI

All disclosed COI were extracted: financial COI (honoraria, eg, for consulting, lectures, scientific articles, training courses, or money for research projects), non-financial COI (eg, researcher allegiance to a psychological therapy, special qualification in a psychological therapy, enthusiasm for a psychological therapy in scientific publications, lectures and research, or inclusion of own primary studies in reviews), and personal COI (eg, employee or private relationship to an employee of a company—regularly addressed as relationships to pharmaceutical companies). If no COI was reported, the websites of the respective journals as well as the guidelines for authors were screened for requirements of COI disclosures at the time of the publication of the review. In addition, we assessed whether review authors included own studies on psychological therapies into their review, and whether this inclusion was disclosed.

Rating of researcher allegiance

In case that a review author included at least one own primary study (which he or she coauthored) into the review, we retrieved these primary studies and rated the researcher allegiance according to information presented in the primary study (note that a rating of researcher allegiance was not possible in the reviews since these do not provide essential information to rate researcher allegiance according to established standards).18–20 Researcher allegiance was rated in 73 of the 86 included primary studies since 13 reviews did not compare psychological therapies to other treatments and were therefore excluded.

Researcher allegiance was defined to be present if the author (1) recommended the respective psychological therapy over another therapy and was (2) either involved in the development of the respective psychological therapy, or (3) was involved in research of/development of the aetiological model of the psychological therapy. Two independent researchers (JvdOS, JB) assessed allegiance in the primary studies, and disagreements were resolved with a third rater (KL). If researcher allegiance was rated to be present in at least one of the primary studies included in a review, this review was rated as afflicted by researcher allegiance. κ Statistics showed substantial inter-rater reliability (k=0.62; agreement 82%).

Assessment of spin in review conclusions

To assess spin in review conclusions, we evaluated whether the conclusion of the review as expressed in the abstract or the discussion section was inconsistent or consistent with the empirical results described in the results section of the review. If the conclusion was consistent with the empirical results, the review was considered as showing no spin. If it was inconsistent, the review was rated as showing spin. Two researchers (KL, JvdOS), who both were blind to the author names of the review as well as the journal having published the review, independently assessed review conclusions and results, and rated whether a spin in review conclusions was present or not. If no consensus was achieved, disagreements were resolved by a third person (JB). κ Statistics showed substantial inter-rater reliability (k=0.70; agreement 87%).

Statistical analyses

The percentage of disclosed COI, researcher allegiance and reviews with spin was calculated. For the first two indicators, the number of reviews was the denominator, the latter indicator was calculated with the number of studies as denominator. The association of researcher allegiance with a spin in the conclusion of reviews is presented as OR with 95% CI. The same procedure was used for the association of the inclusion of own primary studies of the authors in the review, and the disclosure of COI with a spin in the review.

Results

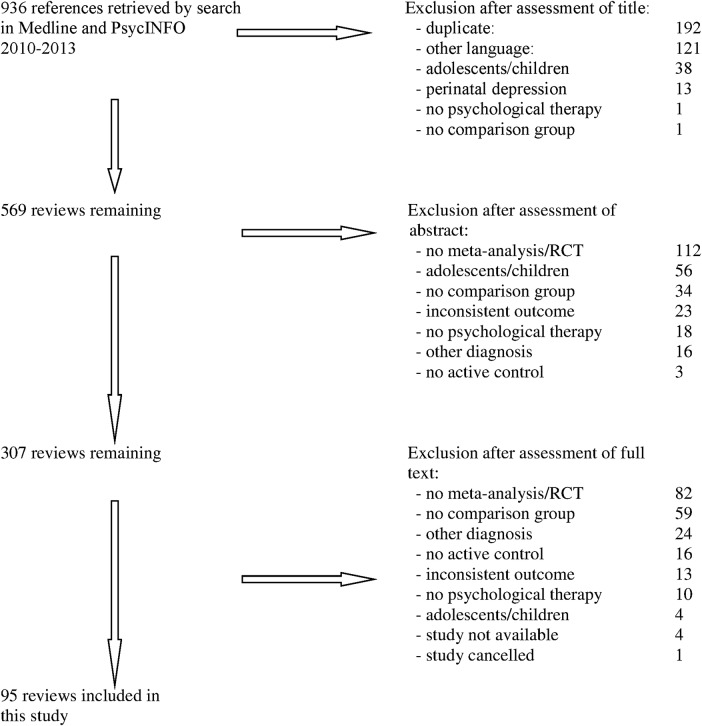

Our search yielded 936 references. After screening and retrieving full-text articles, 95 reviews remained which met our inclusion criteria. A detailed flow chart with a schedule of the reasons for exclusions is found in figure 1. The reviews and meta-analyses addressed anxiety disorders (n=42), depressive disorders (n=48), and/or personality disorders (n=13), and allowed conclusions about the following interventions: 59 reviews compared psychological therapies with other forms of psychological therapies, and 36 compared psychological therapies with pharmacological interventions.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection. RCT, randomised control trial.

Required COI disclosure by journal and disclosed COI

The references of the 95 reviews included in this study are listed in online supplementary table S3. online supplementary table S4 gives an overview how many reviews were published per year and in which journal. Forty of the 50 journals regularly requested a disclosure of COI at the time of publication of the respective review. online supplementary table S5 demonstrates which journal asked for which kind of COI disclosure in the respective year of publication of the review article. In sum: of the 50 publishing journals, 40 requested a disclosure of financial COI (80%), 28 of personal COI (56%), and 17 of non-financial COI (34%).

In 37 of 95 reviews (38.9%), the authors disclosed that no competing interests exist. Authors in 25 of 95 reviews (26.3%) made COI statements as follows: own study included in the review (n=2), research activities in relation to one psychological therapy (n=2), research support (n=18), author has served as consultant (n=4), served as speaker on congresses (n=1), get honoraria (n=5), have holdings (n=2), have patents (n=1), served as a trainer for a psychological therapy (n=1), being influenced as employer (n=1). In other words, financial, non-financial and personal COI were disclosed in 22 reviews (23.1%), 4 reviews (4.2%), and 1 review (1%), respectively. One of the disclosures of financial COI was given in a journal which does not request declaration of COI; the non-financial and personal COI were all given in journals requesting such disclosures. In 33 of 95 reviews (34.7%), no COI statement was made.

Inclusion of own studies into the reviews and researcher allegiance

We also looked at the frequency of the inclusion of own primary studies into the review, and the allegiance of the researcher. Thirty-four of 95 reviews (35.8%) included at least one primary study of one of the review authors. In sum, 86 primary studies (all addressing psychological therapies) were identified which were included in 34 reviews (see online supplementary table S6 for references of these included studies). Twenty reviews included 1 study, 4 reviews 6 studies, 4 reviews 3 studies, 4 reviews 2 studies, 1 review 4 studies and 1 review 18 studies. In 15 of the 34 reviews which included at least one own primary study, we found a researcher allegiance.

Since both the inclusion of own primary studies and researcher allegiance can be described as non-financial COI, we further assessed the disclosure of such COI in relation to the requests of the journal to declare non-financial COI. Regarding the inclusion of own studies into the review, we found: of 34 reviews including own primary studies, inclusion of own studies by review authors was declared in two reviews according to the policy of the journal which specifically asked for inclusion of own studies; was not declared in 16 reviews published in journals requesting the disclosure of non-financial COI (but not defining inclusion of own studies as non-financial COI specifically); and was not declared in 16 reviews published in journals not requesting the disclosure of non-financial COI at all. Regarding researcher allegiance, we found that researcher allegiance was never disclosed: of 15 reviews with a researcher allegiance, researcher allegiance was not declared in nine reviews published in journals requesting the disclosure of non-financial COI (but not defining researcher allegiance as non-financial COI specifically), and was not declared in six reviews published in journals not requesting the disclosure of non-financial COI at all.

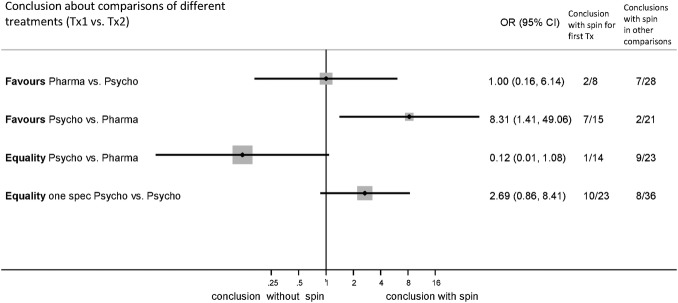

Spin in review conclusions

Spin in the interpretation of review results was rated to be present in 27 of 95 reviews (28%). Within the 36 reviews comparing psychological therapies to pharmacological interventions, nine (25%) showed a spin. In reviews comparing psychological therapies and pharmacological interventions, spin in favour of a specific psychological therapy was more often present as compared with spin in favour of a pharmacological intervention (figure 2). Reviews with a favourable conclusion about psychological therapies (vs pharmacological interventions) are at high risk for a spin in conclusions (OR=8.31 (1.41 to 49.05)), whereas favourable conclusions about effects of pharmacological interventions showed no spin in our sample (OR=1.00 (0.16 to 6.14). Also the conclusion of equal effects of psychological therapies and pharmacological interventions does not face a risk of spin (OR=0.12 (0.01 to 1.08). The conclusion of the equality of effects of psychological therapies, however, showed a trend for a spin, which means that for the primary outcome of interest the review more often states equality despite inequality of treatment effects (OR=2.69 (0.86 to 8.41).

Figure 2.

Risk of spin in review conclusions in comparison with different treatments.

We further explored whether spin in review conclusions is associated with a disclosed COI, the inclusion of own primary studies of the authors, or the researcher allegiance of the authors. To do so, we first investigated these associations in all 95 reviews (table 1). Conclusions with spin were not associated with disclosed COI. However, spin, in conclusions, was related in trend to the inclusion of own studies in the systematic review. Reviews with inclusion of own primary studies showed more often spin than reviews without inclusion of own primary studies of the review authors (OR=2.08 (CI 0.83 to 5.18) p=0.11; table 1). The odds for spin in conclusions in systematic reviews including studies with researcher allegiance was similarly increased, but statistically non-significant (OR=2.63(0.84 to 8.12), p=0.16; table 1).

Table 1.

Association between disclosed conflicts of interest (COI) and other forms of COI (ie, inclusion of primary studies in reviews, researcher allegiance) and spin in review conclusions in all 95 reviews

| Review with spin in conclusion | Review without spin in conclusion | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion of own primary study | 13 | 21 | 2.08 (0.83 to 5.18) |

| No inclusion of own primary study | 14 | 47 | |

| Researcher allegiance | 7 | 8 | 2.63 (0.84 to 8.16) |

| No researcher allegiance | 20 | 60 | |

| COI disclosed | 9 | 16 | 1.63 (0.61 to 4.32) |

| No COI disclosed | 18 | 52 | |

| Inclusion of own primary study, researcher allegiance and/or COI declared | 16 | 31 | 1.74 (0.70 to 4.29) |

| None of the three | 11 | 37 |

Since we were especially interested in spin in favour of psychological therapies, we also investigated whether spin in review conclusions in favour of psychological therapies is associated with a disclosed COI, the inclusion of own primary studies of the authors, or the researcher allegiance of the authors (table 2). However, none of the associations were statistically significant or showed trends.

Table 2.

Association between disclosed conflicts of interest (COI) and other forms of COI (ie, inclusion of primary studies in reviews, researcher allegiance) and spin in review conclusions in the reviews rated as having spin in favour of psychological therapies as compared with all other reviews

| Review rated as ‘spin’ in favour of psychological therapies | Review rated as ‘no spin’ or ‘spin’ against psychological therapies | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion of own primary study | 6 | 28 | 1.24 (0.40 to 3.83) |

| No inclusion of own primary study | 9 | 52 | |

| Researcher allegiance | 2 | 13 | 0.79 (0.16 to 3.94) |

| No researcher allegiance | 13 | 67 | |

| COI disclosed | 4 | 21 | 1.02 (0.29 to 3.56) |

| No COI disclosed | 11 | 59 | |

| Inclusion of own primary study, researcher allegiance and/or COI disclosed | 7 | 40 | 0.88 (0.29 to 2.64) |

| None of the three | 8 | 40 |

Discussion

This study is—at least to our knowledge—the first that systematically assessed the extent and nature of reporting of financial and non-financial COI in systematic reviews of psychological therapies, and that investigated how often these conflicts are disclosed, and whether they may lead to spin in review conclusions. Financial and non-financial COI were disclosed only in 23.1% and 4.2% of the reviews, respectively, although non-financial COI were much more often detectable: review authors had included 86 own studies in approximately one-third of the reviews, and authors of at least 16% of the reviews had allegiance for the evaluated psychological therapy. Spin in review conclusions was found in 27 of 95 reviews (28%), and was associated in trend with a non-financial COI, that is, the inclusion of own primary studies in the systematic review.

Disclosure of financial, non-financial and personal COI

The disclosure of financial COI was requested by 80% of the journals which published the reviews in our study, but only 22 reviews (23.2%) disclosed any financial COI. This may be explained by two reasons: first, systematic reviews focusing on effectiveness of psychological therapies are most often written by psychologists who have rather seldom financial ties to pharmaceutical companies as compared to physicians who often show these relationships,3–7 and second, the minority of reviews (36 of 95 reviews) compared psychological therapies with pharmacological interventions (in 10 of those reviews, financial COI were disclosed). Although psychologists may mostly judge themselves as free of financial COI, however, researcher allegiance, as well as the inclusion of own studies into a review (which we both rated as non-financial COI), may well lead to financial gains indirectly.15 Since psychologists who develop new psychological treatments are often the ones who distribute and train other psychologists in those therapies, the demonstration of effectiveness of a specific psychotherapy in a review may potentially lead to high financial incentives. The promotion of the respective therapy might be easier, and the number of trained psychotherapists with high course fee increases. Showing the effectiveness of a treatment can also be an important step for patents and for the implementation in treatment guidelines. The fact that researchers developing and evaluating the effectiveness of psychological therapies are mostly allied with a specific psychotherapy (eg, cognitive–behavioural therapy or psychoanalysis), makes the issue of COI in psychology therapy research very complex and much more complicated than in pharmacological research. Psychotherapy researchers who realise that the effect of the therapy to which they are allied is less beneficial than another therapy cannot easily switch their research programme to another therapy (since they have often been trained in that therapy for many years), in contrast with a researcher addressing pharmacotherapy who can more easily change his or her research agenda to another drug if a drug proves to be less effective than previously thought. Therefore, researcher allegiance might be present in primary studies in any case to some extent, but needs to be carefully declared in systematic reviews.

Non-financial COI were disclosed only in a very small number of reviews (4.2%) although non-financial COI, such as the inclusion of own primary studies of the review authors (in 34 of 95 reviews) and researcher allegiance (in 15 of 95 reviews), were detectable in a considerable number of them. This low disclosure rate may be explained by three factors: first, only a minority of journals (34% at the time of assessment) request a disclosure of non-financial COI, and all four declarations of non-financial COI were done in these journals; second, only two journals (Perm J and Cochrane Database Syst Rev) specifically asked the authors for the inclusion of own primary studies, and only two others (Psychol Trauma and J Psychiatr Res) asked for circumstances related to the presence of researcher allegiance at the point of our assessment; third, researchers may not see the necessity to declare such COI, although present and requested by the journal asking for non-financial COI. We conclude from this finding that the necessity to declare non-financial COI should be made more transparent in journal articles. The following strategies may be effective: journals should consequently ask their authors to disclose any non-financial COI, should exactly define such conflicts, and should include examples of common causes of non-financial COI, such as the inclusion of own primary studies into review articles or researcher allegiance. Even the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors mainly focuses on financial COI and their disclosures, but gives little emphasis on and advice to the disclosure of non-financial COI.

Similar to non-financial COI, also personal COI were very seldom disclosed (only in one review). This is probably due to the common definition of personal COI meaning any relationship to a person working in a pharmaceutical company. This, of course, is a less relevant COI for psychotherapist assessing treatment effects of psychological therapies. However, psychotherapists, especially the ones who develop new therapies, are very often personally involved in institutes promoting the distribution and training of new psychological therapies. Such personal COI may indirectly lead to considerable financial gains.

Spin in review conclusions

Previous research of our group and others has identified different risks increasing the likelihood of bias in psychotherapeutic outcome research.21 24 In our study, we investigated whether researcher allegiance, an important risk factor of moderate effect size,21 the inclusion of own primary studies into the review, or any declared COI, may be associated with spin in review conclusions, which we found in 27 of the 95 reviews. Both reviews with inclusion of own primary studies and reviews with researcher allegiance showed more often a spin (statistical trend). Since researcher allegiance has been shown to be significantly related to outcome of psychological therapies,21 authors should be transparent in disclosing their own psychotherapeutic training background and the inclusion of own outcome studies in systematic reviews to make an assessment of COI and allegiance easier. The allegiance indicators of our study might be an initial step for such a statement (development of treatment or basic research on the aetiological model for a specific treatment).

Shortcomings

This study has several shortcomings. First, we restricted our search to systematic reviews and meta-analyses of anxiety disorders, personality disorders and major depressive disorders. This may limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, our study is limited to published reports from 2010 onwards. This limits generalisability to earlier reviews, but is justified since COI reporting has become more regular nowadays and authors might not have been asked for a COI statement in earlier submissions. Third, our indicators of COI and allegiance are based on publications, and reporting quality on some indicators was rather low. The inter-rater reliability of both ratings might be much better if reporting standards in journals would be implemented. Fourth, we only checked the disclosed COI, but did not investigate whether authors might have more COI than the disclosed ones. We also did not investigate which authors of a review might be responsible for the evaluation and interpretation of studies addressing different types of interventions (ie, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy), since such investigations are at high risk of being inaccurate and incomplete.

Conclusions and suggestions for the management of COI in psychotherapy outcome research

We conclude that non-financial COI, especially the inclusion of own primary studies into reviews and researcher allegiance, are frequently seen in systematic reviews of psychological therapies and need more transparency. Most policies and journal requirements for COI disclosure focus on the importance of financial COI for risks of bias, and fail to capture the risk of spin associated with an allegiance. Therefore, if journals place more emphasis on the declaration of non-financial COI, declaration rates of non-financial COI by authors will most likely increase. If spin effects of non-financial COI in psychotherapy outcome research are confirmed in further studies, journals should do more than simply providing transparency of COI in order to better manage the impact of COI on research outcomes and publications.15 Strategies to mitigate biases may include the detection and removal of spin at the editorial stage, using independent authors and reviewers interpreting the findings of meta-analyses, the rejection of systematic reviews that demonstrate selective citation biases, and providing free access to all data of systematic reviews to ensure that systematic reviews can be more easily replicated.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by intramural funds from the University Medical Center Mainz, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Mainz, Germany; there was no extramural funding. The authors thank V Stancheva for helping in study extraction.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL designed the study, analysed data, monitored study extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and drafted and revised the manuscript. He is guarantor. JvdOS and NR extracted and analysed data and revised the draft of the manuscript. JS-W analysed data and revised the draft of the manuscript. JB analysed data, monitored study extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: JB was involved in the development of indicators of allegiance. KL, NR, JS-W and JB are psychotherapists trained in CBT, KL and NR also in schematherapy. NR and JB received money from institutes providing training in schematherapy and CBT within the last 3 years. JS-W and KL are coauthors on two reviews included into the study (Gibbon et al, 2010 and Stoffers et al, 2012; see online supplementary table S3), and NR and KL are coauthors on one primary study (Reiss et al, 2014; see online supplementary table S6) included in one of the reviews.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data is available by emailing the corresponding author at Klaus.lieb@unimedizin-mainz.de.

References

- 1.Thompson DF. The challenge of conflict of interest in medicine. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2009;103:136–40. 10.1016/j.zefq.2009.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo B, Field MJ, eds. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice, Institute of Medicine, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell EG. Doctors and drug companies—scrutinizing influential relationships. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1796–7. 10.1056/NEJMp078141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell EG, Rao SR, DesRoches CM et al. . Physician professionalism and changes in physician-industry relationships from 2004 to 2009. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1820–6. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Ehringhaus S et al. . Institutional academic industry relationships. JAMA 2007;298:1779–86. 10.1001/jama.298.15.1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieb K, Brandtönies S. A survey of German physicians in private practice about contacts with pharmaceutical sales representatives. Dt Arztebl Int 2010;107:392–8. 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e110130 10.1371/journal.pone.0110130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:454–65. 10.1001/jama.289.4.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schott G, Pachl H, Limbach U et al. . The financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies and its consequences. Part 1: a qualitative, systematic review of the literature on possible influences on the findings, protocols, and quality of drug trials. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;107:279–85. 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang AT, McCoy CP, Murad MH et al. . Association between industry affiliation and position on cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone: cross sectional systematic review. BMJ 2010;340:c1344 10.1136/bmj.c1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn AG, Arachi D, Hudgins J et al. . Financial conflicts of interest and conclusions about neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza: an analysis of systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:513–18. 10.7326/M14-0933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roest AM, de Jonge P, Williams CD et al. . Reporting bias in clinical trials investigating the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of anxiety disorders: a report of 2 meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:500–10. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA et al. . Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. JAMA 2011;305:1008–17. 10.1001/jama.2011.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roseman M, Turner EH, Lexchin J et al. . Reporting of conflicts of interest from drug trials in Cochrane reviews: cross sectional study. BMJ 2012;345:e5155 10.1136/bmj.e5155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark AM, Choby A, Ainsworth K et al. . Addressing conflict of interest in non-pharmacological research. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:270–2. 10.1111/ijcp.12569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leykin Y, DeRubeis RJ. Allegiance in psychotherapy outcome research: separating association from bias. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2009;16:54–65. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01143.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert MJ. Are differential treatment effects inflated by researcher therapy allegiance? Could Clever Hans count? Clin Psychol Sci Pract 1999;6:127–30. 10.1093/clipsy/6.1.127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaffan EA, Tsaousis I, Kemp-Wheeler SM. Researcher allegiance and meta-analysis: the case of cognitive therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:966–80. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.6.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munder T, Gerger H, Trelle S et al. . Testing the allegiance bias hypothesis: a meta-analysis. Psychother Res 2011;21: 670–84. 10.1080/10503307.2011.602752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller S, Wampold B, Varhely K. Direct comparisons of treatment modalities for youth disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychother Res 2008;18:5–14. 10.1080/10503300701472131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munder T, Brütsch O, Leonhart R et al. . Researcher allegiance in psychotherapy outcome research: an overview of reviews. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:501–11. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munder T, Flückiger C, Gerger H et al. . Is the allegiance effect an epiphenomenon of true efficacy differences between treatments? a meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 2012;59:631–7. 10.1037/a0029571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD et al. . The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:280–91. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E et al. . The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol Med 2010;40:211–23. 10.1017/S0033291709006114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010606supp.pdf (334.7KB, pdf)