Abstract

Objectives

Internet-delivered exposure-based cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) has been shown to be effective in the treatment of severe health anxiety. The health economic effects of the treatment have, however, been insufficiently studied and no prior study has investigated the effect of ICBT compared with an active psychological treatment. The aim of the present study was to investigate the cost effectiveness of ICBT compared with internet-delivered behavioural stress management (IBSM) for adults with severe health anxiety defined as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) hypochondriasis. ICBT was hypothesised to be the more cost-effective treatment.

Setting

This was a cost-effectiveness study within the context of a randomised controlled trial conducted in a primary care/university setting. Participants from all of Sweden could apply to participate.

Participants

Self-referred adults (N=158) with a principal diagnosis of DSM-IV hypochondriasis, of whom 151 (96%) provided baseline and post-treatment data.

Interventions

ICBT or IBSM for 12 weeks.

Primary and secondary measures

The primary outcome was the Health Anxiety Inventory. The secondary outcome was the EQ-5D. Other secondary measures were used in the main outcome study but were not relevant for the present health economic analysis.

Results

Both treatments led to significant reductions in gross total costs, costs of healthcare visits, direct non-medical costs and costs of domestic work cutback (p=0.000–0.035). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) indicated that the cost of one additional case of clinically significant improvement in ICBT compared with IBSM was $2214. The cost-utility ICER, that is, the cost of one additional quality-adjusted life year, was estimated to be $10 000.

Conclusions

ICBT is a cost-effective treatment compared with IBSM and treatment costs are offset by societal net cost reductions in a short time. A cost-benefit analysis speaks for ICBT to play an important role in increasing access to effective treatment for severe health anxiety.

Trial registration number

NCT01673035; Results.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A randomised controlled design was used.

Attrition rates were low.

A prospective societal perspective was used.

Two internet-based treatments were compared, but we did not include a trial arm with conventional face-to-face treatment.

Introduction

Several features of severe health anxiety, here defined as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) hypochondriasis, lead to high societal costs of illness. These features include severe health anxiety, which is associated with increased healthcare consumption and functional impairment.1 2 It is also a relatively common disorder and, in the absence of treatment, it is chronic for most patients.3 4 Since health anxiety can be viewed as a dimensional phenomenon, ranging from adaptive concerns to severely debilitating anxiety,5 the term severe health anxiety is used in this paper to denote our reference to clinically significant impaired individuals meeting diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV hypochondriasis.

Although previously considered a disorder highly difficult to treat, in the past 15 years, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has emerged as an empirically supported treatment for severe health anxiety yielding large reductions of health anxiety.6 Few studies have, however, investigated whether CBT is a cost-effective treatment. This type of analysis means relating the additional gains to the additional costs of an experimental treatment compared with an alternative, such as another treatment or wait list.7 Cost-effectiveness analysis is highly important as it provides information that can be used to guide treatment decisions, so that more patients can be treated effectively and waiting times reduced. Two studies have analysed cost effectiveness of CBT for severe health anxiety delivered in a conventional face-to-face format compared with treatment as usual using data from randomised controlled trials.8 9 In the first study, it was found that CBT but not the control condition reduced consumption of primary and secondary healthcare contacts, but total costs were unchanged in both conditions.8 In the second study, a large-scale randomised trial, the health economic analyses showed that there were no significant differences between the two treatment conditions.9 In both of the above studies, CBT was superior in reducing health anxiety symptoms compared with treatment as usual, which means that as costs were similar across groups, CBT is likely to be the more cost-effective treatment option.

Our research group has developed an internet-delivered exposure-based CBT (ICBT), which has been shown to be effective in reducing health anxiety in two randomised controlled trials.10 11 In terms of format, ICBT can be described as internet-based bibliotherapy with online therapist support through a secure asynchronous online messaging system.11 12 ICBT carries several advantages, with one of the most essential being that it can increase access to psychological treatment for severe health anxiety as each therapist can have up to 80 patients in ongoing treatment. Only one health economic evaluation of ICBT for severe health anxiety has been conducted, and in that study it was found that the treatment was highly cost-effective in comparison to a basic attention control condition that did not receive active treatment.13 The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was −£1244, meaning that each case of improvement in ICBT relative to the control condition generated a societal net economic gain of £1244. That is, the results suggested that when providing ICBT instead of no treatment, the most likely outcome is that patients are improved while society reduces its costs for health anxiety. No prior study has, however, investigated whether ICBT is cost-effective when compared with an active and comprehensive psychological treatment. In the most recently conducted trial of ICBT, we compared it with internet-delivered behavioural stress management (IBSM), which contrasts with ICBT in the sense that it is based on taking direct control over symptoms through stress management and applied relaxation. The results showed that both treatments caused large improvements in health anxiety but that participants who received ICBT made significantly larger reductions of health anxiety than those in IBSM.12 This trial provides an excellent opportunity for investigating the cost effectiveness of ICBT compared with an active treatment and adds to the limited body of knowledge on health economic aspects of CBT for severe health anxiety.

The aim of this study was to investigate the cost effectiveness of ICBT versus IBSM for severe health anxiety featuring a societal perspective and using randomised trial data. Our hypothesis was that ICBT would be cost-effective compared with IBSM using the criteria of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),14 that is, that an additional case of improvement or quality-adjusted life year (QALY) would be achieved at a cost not exceeding £20000.

Methods

Design of the study

This study used a prospective cost-effectiveness analysis design and a societal perspective was taken. This meant that direct costs, for example, healthcare consumption, as well as indirect costs, for example, work cutback, were assessed and analysed. Data were collected within the context of a randomised controlled trial of ICBT (n=79) and IBSM (n=79) for adults with severe health anxiety. As outlined by Saha and et al,15 cost-effectiveness analysis is a combined measure of the incremental costs and gains of a new treatment compared with an alternative. The outcome, ICER, gives an estimate of the cost for one additional unit of improvement when administering ICBT compared with IBSM. Information about how the ICER is calculated is provided below under Data analysis. The trial was pre-registered with clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier NCT01673035). All participants provided written (through a web portal) informed consent. This procedure was approved by the ethics committee.

Participants and recruitment

The total sample comprised 158 adult participants with severe health anxiety, of whom 79 were randomised to ICBT and 79 to IBSM. The mean age was 41.7 years (SD=13.6) in ICBT and 41.4 years (SD=13.2) in IBSM. There were 64 women (81%) in the ICBT group and the participants had suffered from health anxiety for 13 years on average (SD=13.1). In the IBSM group, there were 61 women (77%) and the participants had experienced symptoms of health anxiety for 14 years (SD=13.1). The study was conducted at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, but recruitment was carried out nationwide. To be included in the study, participants who applied had to: (1) have a principal diagnosis of severe health anxiety (hypochondriasis) according to DSM-IV, (2) be at least 18 years old, (3) have no ongoing or prior episode of bipolar disorder or psychosis, (4) have no ongoing substance abuse or addiction, (5) have stable dosage since at least 2 months if on antidepressant or anxiolytic medication and agree to keep the dosage constant throughout the study, (6) not have severe depressive symptoms or serious suicide ideation as indicated by a total score or ≥31 or ≥4 on item 9 of the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-Self-rated (MADRS-S16), (7) receive no concurrent psychological treatment for severe health anxiety and have no history of completed CBT for severe health anxiety during the past 3 years and (8) have no serious somatic disorder to which the health anxiety would be an adequate response. Diagnostic assessments were conducted using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule. A more detailed description of the recruitment procedure is presented in the Hedman et al12 paper.

Treatments

Both treatments comprised extensive self-help texts divided into 12 modules with associated homework exercises and participants were expected to complete at least one module per week during the 12-week treatments. Participants accessed the modules through a secure internet-based treatment platform. Throughout the treatment, an online therapist guided participants and provided feedback on homework exercises through an asynchronous messaging system similar to email. As a main principle, the patient is exposed to the same treatment components as in face-to-face treatment.

Internet-delivered exposure-based CBT

The main intervention component was systematic exposure to health anxiety-related situations or events in combination with response prevention. As described in the main outcome paper,12 an example of this could be to trigger feared bodily sensations through physical exercise (exposure) while refraining from checking that the pulse is normal (response prevention). Mindfulness training was used throughout the treatment as a way to enhance exposure, that is, it was not a stand-alone intervention but used as a way to increase the possibility that patients would conduct exposure exercises. This meant that participants were encouraged to use mindfulness techniques as a means to handle anxiety triggered by exposure. The treatment thus differed in this regard from the mindfulness-based cognitive treatment by McManus et al,17 where mindfulness training is the main treatment component. Treanor18 has suggested that mindfulness training could facilitate extinction learning during exposure through increasing awareness of conditioned triggers of anxiety. The treatment was conducted within an exposure-extinction paradigm and patients were encouraged to use mindfulness and acceptance towards aversive internal events. This treatment has previously been shown to be effective both when given as face-to-face therapy19 and via the internet.10 12 20

Internet-delivered behavioural stress management

The main components of IBSM were applied relaxation and various stress management strategies including activity scheduling, structured problem-solving and increasing recuperating activities. IBSM differed from ICBT in the important sense that it focused on direct symptom control rather than on exposure to health anxiety-related events. That is, when feeling anxious, participants were encouraged to use applied relaxation and stress reduction techniques to take direct control over health anxiety symptoms. The treatment was similar to the behavioural stress management for severe health anxiety tested in a face-to-face format by Clark et al.21 Applied relaxation did not strictly follow but was inspired by the treatment developed by Ost22 and had previously been tested as an internet-based intervention.23 The programme started with progressive relaxation, followed by release-only relaxation, conditioning a relaxed state to a verbal cue, and applying rapid relaxation in distressing situations.

Clinical outcome assessment

The Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI24) was the primary outcome measure. This instrument has been shown to be a highly reliable health anxiety measure (test-retest r=0.90 and Cronbach's α=0.95).

In order to assess health-related quality of life, we used the EQ-5D.25 This is an instrument designed to be a generic measure of quality of life and suitable for a wide range of patient groups. It assesses mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.26

Cost assessment

We used the Trimbos and Institute of Medical Technology Assessment Cost Questionnaire for Psychiatry (TIC-P27) to collect economic cost data. The TIC-P is a self-report measure that covers three economic domains: direct medical costs, indirect medical costs and indirect non-medical costs. Direct medical costs are those associated with healthcare consumption, such as emergency care visits or visit to a psychiatrist. Indirect medical costs are costs that are related to the clinical problem, but not considered healthcare, such as participating in self-help groups. Finally, indirect non-medical costs are those related to loss of productivity, such as costs for sick leave or domestic productivity loss. When estimating costs of productivity loss, we used the human capital approach, which means that monetary losses for the duration of the entire period of productivity loss were taken into account.28 The costs were initially assessed in Swedish krona (Kr) and converted into US$ using 2013 as the reference year, yielding a Kr1 equivalent of US$0.1535. Costs of healthcare services and medications were, when available, obtained from official healthcare tariff indexes for services offered within the publicly funded healthcare system. The costs of the ICBT and IBSM were modelled as a function of therapist time using the same healthcare index to determine therapist tariffs, that is, tariffs for licensed psychologists.

Procedures

Participants were randomised to ICBT or IBSM in a 1:1 ratio using no restriction or matching. Randomisation took place after inclusion assessment, meaning that no allocation bias could be present in terms of assessors knowing the status of forthcoming allocations. Clinical and health economic data of this study were collected at baseline, that is, before treatment start and at post-treatment. Self-report assessments were conducted using a secure online assessment system. Internet administration has been shown to be a reliable format for measures of psychiatric symptoms and quality of life.29

Data analysis

STATA IC/V.11.0 (Stata Corp) and SPSS V.22.0 (IBM) were used to conduct the statistical analyses. Clinical data were analysed using a mixed-effects model approach for repeated data using time and treatment group as independent variables.30 Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d based on pooled SDs.

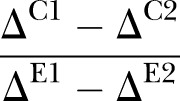

As for the health economic analyses, we estimated ICERs using the formula:

|

C1–C2 is the net difference in cost change between ICBT and IBSM at post-treatment and E1–E2 refers to the net difference in effectiveness of the two conditions.28 The total net difference in costs was thus divided by the net difference in effectiveness. In this study, effectiveness in the ICER formula was defined as the proportion of participants who showed clinically significant improvement.31 The criteria for clinically significant improvement were that participants had to be improved by at least 18 points on HAI and have an end point score of 66 or lower. Participants classified as clinically significantly improved were thus reliably improved beyond what could be expected from measurement error using the Jacobson and Truax formula31 (pretreatment to post-treatment change divided by the SE of the difference between scores) and were closer to the healthy population than to the clinical population. Healthy control scores were obtained from the study by Salkovskis et al24 and baseline scores of participants of this study were used as a reference for the clinical population. The ICER calculations were conducted using a bootstrap framework (5000 replications) generating an estimated figure of the incremental costs of ICBT compared with IBSM in relation to ICBT's incremental effectiveness. Using bootstrap sampling methods increases the reliability of SEs and cost distribution estimates.32

Cost-utility analysis was also conducted, which is the same type of analysis as cost-effectiveness analysis, with the exception that the net cost of an incremental QALY is calculated instead of a disorder-specific outcome measure28 using the EQ-5D and applying the quality of life weights as described by the EuroQol Group.33 This meant that the cost-utility ICER was modelled as the ratio of the net between-group cost change difference and the net EQ-5D change difference. For cost-effectiveness and cost-utility ICERs, we modelled graph planes comprising 5000 simulated ICERs in order to estimate the uncertainty around the ICER. We also modelled cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which is the proportion of scatter points falling south and east of a range of slopes through the origin of the ICER plane where a slope coefficient of 0 (equivalent to the x-axis) represents that willingness to pay (WTP) is 0 and 1 (equivalent to the y-axis) that WTP is infinite.34 Within-group cost changes were analysed using sign tests due to non-normality of the cost data. For the same reason, we used Mann–Whitney U tests to analyse between-group cost differences and Spearman's r to assess association between improvement in health anxiety and gross total changes. Since attrition rates were very low, we imputed missing cost data carrying the last known observation forward.

Results

Attrition and health anxiety outcome

Of the 158 participants, 158 (100%) completed assessments at baseline and 151 (96%) provided data at post-treatment. As previously reported, the pretreatment to post-treatment effect size on the primary outcome of health anxiety HAI was d=1.8 in the ICBT group and d=1.2 in the IBSM group, indicating that both treatments yielded large improvements in health anxiety.12 Mixed-effects models analysis showed that ICBT led to significantly larger reductions of health anxiety compared with IBSM (F=3.9; df=2, 121; p=0.022; between-group d at post-treatment=0.3).

Cost changes

Table 1 presents estimates of costs across assessment points for ICBT and IBSM. In ICBT and IBSM, there were significant reductions in gross total costs, healthcare visit costs, direct non-medical costs and costs of domestic work cutback (Z=−5.78–2.11; p=0.000–0.035). Participants in IBSM also reduced their medication costs (Z=−2.97; p=0.006), whereas ICBT participants did not (Z=−0.38; p=0.703). None of the groups had any cost changes regarding unemployment or sick leave (Z=−0.16–0.00; p=0.289–1.000). Mann-Whitney U tests showed no baseline or post-treatment between-group differences on any of the above type of costs (U=2614–3099; p=0.073–0.938). The slight difference in intervention costs (table 1) was due to the somewhat more therapist time used in ICBT (median minutes/week=11.0) compared with IBSM (median minutes/week=9.2).

Table 1.

Costs by type of expenditure

| Cost | Baseline |

Post-treatment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICBT |

IBSM |

ICBT |

IBSM |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Direct medical | 569 | 773 | 547 | 552 | 337 | 407 | 354 | 403 |

| Healthcare visits | 562 | 770 | 540 | 550 | 331 | 405 | 350 | 404 |

| Medication | 7 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| Direct non-medical costs | 173 | 370 | 129 | 224 | 139 | 374 | 106 | 269 |

| Indirect costs | 507 | 1059 | 621 | 1199 | 561 | 1392 | 439 | 910 |

| Unemployment | 238 | 926 | 354 | 1070 | 250 | 968 | 167 | 733 |

| Sick leave | 71 | 293 | 146 | 489 | 78 | 296 | 132 | 390 |

| Work cutback | 133 | 382 | 72 | 155 | 199 | 801 | 104 | 334 |

| Domestic | 65 | 140 | 49 | 173 | 34 | 68 | 37 | 125 |

| Gross total costs | 1249 | 1585 | 1297 | 1443 | 1036 | 1572 | 909 | 1077 |

| Intervention costs | – | – | 571 | 431 | ||||

| Net total costs | 1607 | 1698 | 1340 | 1123 | ||||

All costs in $USD.

IBSM, internet-based behavioural stress management; ICBT, internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy.

Association of cost and health anxiety changes

As indicated by Spearman's r analysis, there was a significant association between gross total cost changes and improvement in health anxiety as measured by HAI among participants in the ICBT group (r=0.31; p=0.005) but not in the IBSM group (r=0.17; p=0.143). That is, participants in ICBT who made larger reductions of health anxiety lowered their costs more than did those who were less improved.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

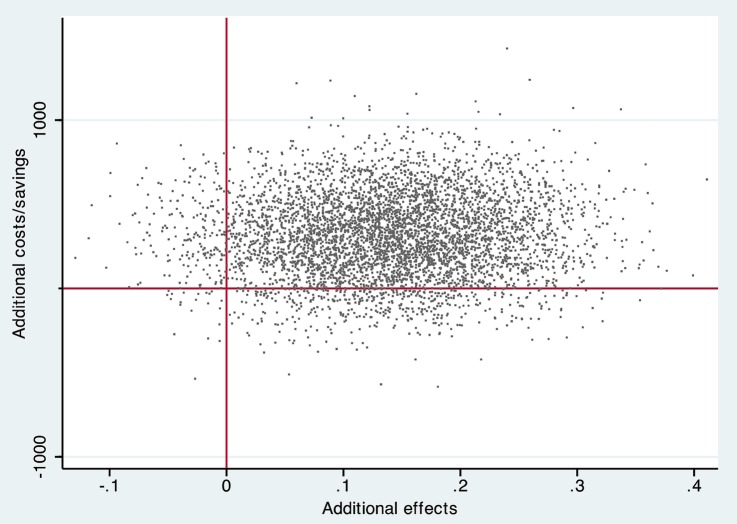

The cost-effectiveness ICER was estimated to be 310/0.14=2214, indicating that each additional case of clinically significant improvement in ICBT (total n improved=38 (48%)) compared with IBSM (total n improved=27 (34%)) was associated with a societal cost of $2214. This was driven by slightly higher total net costs in ICBT than in IBSM and that participants in ICBT were more likely to be clinically significantly improved. The simulation of scattered ICERs is presented in figure 1 where ICERs located in the southeastern quadrant suggest that ICBT is more effective at a lower net societal cost, whereas ICERs in the northwestern quadrant indicates that ICBT is less effective and more costly. Of the ICERs in figure 1, 4340 (87%) are located in the northeast quadrant, indicating that the most likely outcome is that ICBT generates larger improvements at additional net societal costs. Of the remaining ICERs, 436 (9%) are located in the southeastern quadrant, 203 (4%) in the northwestern quadrant and 21 (<1%) in the southwestern quadrant.

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane comparing internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) to internet-based behavioural stress management (IBSM).

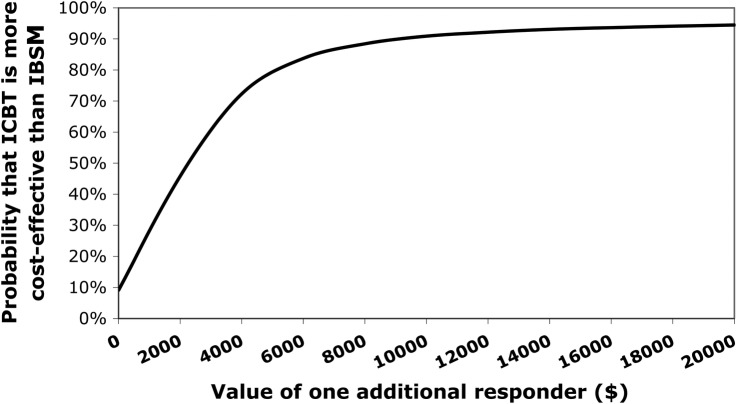

Figure 2 displays a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve where estimates vary as a function of societal WTP for an additional case of improvement. As shown in figure 2, ICBT has a 9% probability of being cost-effective compared with IBSM if WTP for an additional improvement is $0. If WTP is increased to $4000, the probability of ICBT being more cost-effective increases to 72% and if society were willing to pay $10 000 for an additional case of clinically significant improvement, the probability of ICBT being cost-effective compared with IBSM is 91%.

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve comparing internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) to internet-based behavioural stress management (IBSM).

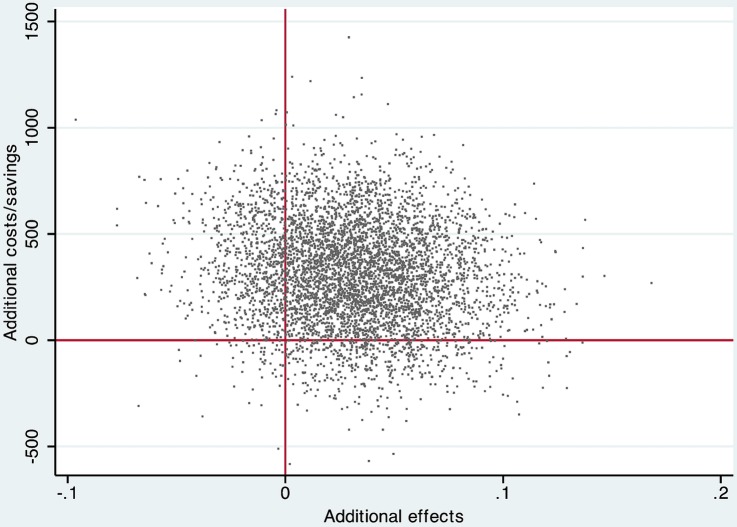

Cost-utility analysis

The cost-utility ICER was 310/0.031=10 000, indicating that the incremental cost of one QALY in ICBT relative to IBSM was $10 000. The cost-utility ICER plane in figure 3 displays the scatter of the 5000 bootstrapped ICERs. The distribution of ICERs in the four quadrants is as follows: 3770 (75%) are located in the northeastern quadrant, 773 (15%) are in the northwestern quadrant, 401 (8%) are in the southeastern quadrant and 56 (1%) are located in the southwestern quadrant. Thus, the most likely outcome is that ICBT in comparison to IBSM generates larger improvements in health-related quality of life at a larger net societal cost.

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness utility plane comparing internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) to internet-based behavioural stress management (IBSM).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the cost effectiveness of ICBT and IBSM for severe health anxiety featuring a societal perspective. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second study to assess ICBT from a health economic view and the first to investigate the cost effectiveness of two comprehensive psychological treatments for severe health anxiety. The results showed that both treatments significantly reduced the gross total costs, which were driven by lowered costs of healthcare visits, direct non-medical costs and costs of domestic work cutback. The cost-effectiveness ICER indicated that the cost of one additional case of clinically significant improvement, when treating patients with ICBT instead of IBSM, was $2214 while the cost-utility ICER was $10 000. Taken together, the findings indicate that ICBT is a cost-effective treatment in comparison to IBSM.

In comparison to the previously conducted study investigating cost effectiveness of ICBT for severe health anxiety,13 the findings of this study showed a substantially higher ICER estimate. Since ICBT displayed very similar outcomes both in terms of treatment pre-to-post effects and costs as in the previous randomised trial,10 the difference in ICERs across studies is explained by how the comparator performed. IBSM was much more effective in reducing health anxiety than the basic control condition in the first trial and also made significant cost reductions. Since ICER is a relative measure, this explains the higher ICER of this study. Having said that, it is important to underscore that the ICERs of this study were rather small in a broader perspective and clearly below the suggested cost-effectiveness limit proposed by NICE, which is £20 000.14 The threshold for what should be considered a cost-effective treatment is of course to some extent arbitrary and varies between countries. As described by Mihalopoulos and Chatterton,14 the WHO on Macroeconomics and Health has suggested that a general cost-effectiveness criterion should be that if the cost of a disability-adjusted life year (DALY) does not exceed the average income per capita in a given country, the treatment can be considered very cost-effective.35 In 2013, the average annual income in Sweden was approximately US$42 500,36 meaning that also when using the WHO's criterion, the findings of this study indicate that ICBT is cost-effective.

To summarise, ICBT is extremely cost-effective in comparison to no treatment and cost-effective compared with IBSM. These results fit well with the cost-effectiveness studies of face-to-face CBT compared with active control conditions, which showed that gross total costs were similar in both treatment conditions but that patients who underwent CBT made larger improvements.8 9

This study has several important implications. First, the societal net costs of providing ICBT were estimated to be offset in a time frame as short as about 3 months. That is, the societal net cost savings exceed the cost of treatment in a short time period, which is important for policymakers, as ICBT thereby is a win-win treatment option in the sense that patients are improved at no longer term net cost. Second, since the main part of cost reductions was in the realm of healthcare consumption, it could mean that the agent that allocates resources to treat severe health anxiety will benefit through overall reduced resource use. For example, it may be that implementing ICBT for this patient group in primary care could lead to reduced strain on general practitioners as the demand for their services decreases as severe health anxiety decreases. The significant association of health anxiety reduction and cost reduction found in this study and in a previous clinical trial of the same treatment delivered in a face-to-face format19 provides empirical support for this. In line with this are also the results from the trial by Seivewright and et al8 where it was found that CBT led to reduced healthcare consumption. Third, since each therapist can treat four times as many patients as in a face-to-face CBT, this internet-delivered treatment can be an effective means of making CBT accessible to patients with severe health anxiety.

The central strengths of this study were the randomised design allowing for control over confounders, the high completion rates and the prospective societal perspective. As for limitations, this study relied on self-report to obtain cost data, but this was regarded as acceptable against the background that studies have demonstrated high convergence between registry data and health economic estimates collected through self-report.37 A second limitation was that we did not include a treatment arm of face-to-face CBT, which constitutes a highly important comparison treatment. This is an area for future research, and although available effect size data suggest that face-to-face CBT and ICBT for severe health anxiety produce similar effects, it cannot be ruled out that the additional direct costs of face-to-face CBT are balanced through larger health anxiety reductions.

On the basis of the findings of this study, we conclude that ICBT is a cost-effective treatment compared with IBSM and that the treatment leads to societal cost reductions offsetting the cost of intervention in a short time frame. ICBT has the potential to reduce suffering from a debilitating disorder while at the same time reducing strain on limited healthcare resources. Implementing ICBT could thus potentially be highly cost-effective not just from a societal perspective but also from a healthcare provider perspective. ICBT could play an important role of making effective psychological treatment accessible to patients with severe health anxiety.

Footnotes

Contributors: EH conceived the study, collected data, interpreted the data, analysed the data and drafted the paper. EA, BL and EAx conceived the study, collected data, interpreted the data and drafted the paper. ML conceived the study, interpreted the data and drafted the paper.

Funding: This study was funded by Karolinska Institutet and by research grants from Stockholm County Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Seivewright H, Salkovskis P, Green J et al. . Prevalence and service implications of health anxiety in genitourinary medicine clinics. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:519–22. 10.1258/0956462041558122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink P, Ørnbol E, Christensen KS. The outcome of health anxiety in primary care. A two-year follow-up study on health care costs and self-rated health. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e9873 10.1371/journal.pone.0009873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyrer P, Cooper S, Crawford M et al. . Prevalence of health anxiety problems in medical clinics. J Psychosom Res 2011;71:392–4. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barsky AJ, Fama JM, Bailey ED et al. . A Prospective 4- to 5-year study of DSM-III-R hypochondriasis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:737–44. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramowitz JS, Braddock AE. Psychological treatment of health anxiety and hypochondriasis: a biopsychological approach. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olatunji BO, Kauffman BY, Meltzer S et al. . Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hypochondriasis/health anxiety: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. Behav Res Ther 2014;58:65–74. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King JT Jr, Tsevat J, Lave JR et al. . Willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life year: implications for societal health care resource allocation. Med Decis Making 2005;25:667–77. 10.1177/0272989X05282640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seivewright H, Green J, Salkovskis P et al. . Cognitive-behavioural therapy for health anxiety in a genitourinary medicine clinic: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2008;193:332–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyrer P, Cooper S, Salkovskis P et al. . Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:219–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61905-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedman E, Andersson G, Andersson E et al. . Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for severe health anxiety: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:230–6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedman E, Axelsson E, Görling A et al. . Internet-delivered exposure-based cognitive-behavioural therapy and behavioural stress management for severe health anxiety: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:307–14. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.140913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedman E, Andersson E, Lindefors N et al. . Cost-effectiveness and long-term effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for severe health anxiety. Psychol Med 2013;43:363–74. 10.1017/S0033291712001079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mihalopoulos C, Chatterton ML. Economic evaluations of interventions designed to prevent mental disorders: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry 2015;9:85–92. 10.1111/eip.12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha S, Hoerger TJ, Pignone MP et al. . The art and science of incorporating cost effectiveness into evidence-based recommendations for clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:36–43. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00260-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svanborg P, Åsberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;89:21–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McManus F, Surawy C, Muse K et al. . A randomized clinical trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus unrestricted services for health anxiety (hypochondriasis). J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:817–28. 10.1037/a0028782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treanor M. The potential impact of mindfulness on exposure and extinction learning in anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:617–25. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Andersson E et al. . Effectiveness and cost offset analysis of group CBT for hypochondriasis delivered in a psychiatric setting: an open trial. Cogn Behav Ther 2010;39:239–50. 10.1080/16506073.2010.496460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedman E, Andersson E, Lindefors N et al. . Cost-effectiveness and long-term effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for severe health anxiety. Psychol Med 2013;43:363–74. 10.1017/S0033291712001079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A et al. . Two psychological treatments for hypochondriasis. A randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ost LG. Applied relaxation: description of a coping technique and review of controlled studies. Behav Res Ther 1987;25:397–409. 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90017-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Andersson E et al. . Internet-delivered exposure-based treatment vs. stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1481–91. 10.1038/ajg.2011.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HM et al. . The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med 2002;32:843–53. 10.1017/S0033291702005822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EuroQol-Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Donker MCH. Manual/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness (TIC-P). Institute of Medical Technology Assessment (iMTA) Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrence GW et al. . Methods for the evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Rück C et al. . Internet administration of self-report measures commonly used in research on social anxiety disorder: a psychometric evaluation. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26:736–40. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:310–17. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108. 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fenwick E, Byford S. A guide to cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:106–8. 10.1192/bjp.187.2.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and Health: investing in health for economic development. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Executive Summary Geneva, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Statistics Sweden. Total income from employment and business 2013, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel A, Rendu A, Moran P et al. . A comparison of two methods of collecting economic data in primary care. Fam Pract 2005;22:323–7. 10.1093/fampra/cmi027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]