Abstract

Objectives

It has been suggested that since 1990, de-institutionalisation of mental healthcare in Western Europe has been reversed into re-institutionalisation with more forensic beds, places in protected housing services and people with mental disorders in prisons. This study aimed to identify changes in the numbers of places in built institutions providing mental healthcare in Western Europe from 1990 to 2012, and to explore the association between changes in psychiatric bed numbers and changes in other institutions.

Settings and data

Data were identified from 11 countries on psychiatric hospital beds, forensic beds, protected housing places and prison populations. Fixed effects regression models tested the associations between psychiatric hospital beds with other institutions.

Results

The number of psychiatric hospital beds decreased, while forensic beds, places in protected housing and prison populations increased. Overall, the number of reduced beds exceeded additional places in other institutions. There was no evidence for an association of changes in bed numbers with changes in forensic beds and protected housing places. Panel data regression analysis showed that changes in psychiatric bed numbers were negatively associated with rising prison populations, but the significant association disappeared once adjusted for gross domestic product as a potential covariate.

Conclusions

Institutional mental healthcare has substantially changed across Western Europe since 1990. There are ongoing overall trends of a decrease in the number of psychiatric hospital beds and an increase in the number of places in other institutions, including prisons. The exact association between these trends and their drivers remains unclear. More reliable data, information on the characteristics of patients in different institutions, long-term pathway analyses and effectiveness studies are required to arrive at evidence-based policies for the provision of institutional mental healthcare.

Keywords: mental health services, institutional care, de-institutionalisation, re-institutionalization, psychiatric beds, prison populations

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a large longitudinal study on different types of institutional mental healthcare, including prison populations, forensic beds and protected housing places, in Western Europe over a period of 22 years.

The study includes countries from different regions within Western Europe and used what are arguably the best available data.

The analysis of associations between hospital beds and prison places considered gross domestic product as a covariate representing other societal time trends.

The accuracy of some of the data remains questionable, data on forensic beds and protected housing places were incomplete, and definitions of the different categories of institutions vary across countries.

The number of data points is too small for reliable time series analyses, and there are no data on the characteristics of patients in the different institutions.

Background

Since the 1950s, major reforms have changed mental healthcare across Western Europe. These reforms were characterised by the process of ‘de-institutionalisation’.1 Although the term ‘de-institutionalisation’ has been used inconsistently in the literature, it usually refers to the closure or downsizing of former large asylums and the development of various services in the community.2 3 These community services are intended to provide care for people with mental disorders, including those with severe mental illnesses who would have been long-term hospitalised before ‘de-institutionalisation’. Psychiatric in-patient treatment was provided in smaller units,4 often linked to general district hospitals, with a focus on short-term acute care. Various forms of protected housing services should support those patients who could not—or not yet—live independently, while all other patients were supposed to live outside mental healthcare institutions. Reasons for these reforms included the concern that asylums were therapeutically ineffective and even detrimental, as well as the attitude that civil rights entitled patients to a life as autonomous as possible.5 6

Although the political context, drivers, timing, pace and exact outcomes of de-institutionalisation varied across countries, changes were implemented everywhere, often supported by substantially increased funding for mental healthcare.7

However, previous analyses of changes in the provision of institutional mental healthcare in Europe suggested that the trend might have been reversed. Since 1990—according to historians the end of the post-war period in Europe—the number of conventional psychiatric beds decreased further. Yet, in most studied countries, the places in protected housing services and of forensic psychiatric beds increased as did the prison population, which may be assumed to include a large and possibly rising number of prisoners with mental illnesses. Considering this increase in institutions accommodating people with mental disorders, previous analyses suggested that ‘de-institutionalisation’ of mental healthcare might have been superseded by ‘re-institutionalisation’.8–14 This leads to questions as to whether the trend continued and, if so, whether the total number of additional places in alternative institutions (ie, protected housing facilities, forensic hospitals, prisons) was greater than the reduction in hospital beds so that overall there has indeed been a re-institutionalisation.

A further question is whether changes in different forms of institutional care are associated, for example, whether drastic reductions in bed numbers are associated with a more marked increase in protected housing places or in the prison populations. The latter association, that is, an inverse relationship between psychiatric hospital beds and the size of the prison populations, was first suggested by Penrose15 in 1939, based on a cross-sectional observational study in 18 European countries. He concluded that a fixed proportion of people were required to be kept in institutions and that the provision of more psychiatric hospital beds could help to reduce the prison populations.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have tried to test the Penrose hypothesis with inconsistent conclusions.16–21 Yet only longitudinal studies can explore whether changes in hospital beds and the prison population are really linked. Kelly16 found a strong rank correlation in Ireland between 1963 and 2003; specifically, a decline in psychiatric inpatients significantly exceeded the increase of prisoners. Replicating the method of Kelly, Mundt et al20 did not find a correlation in post-communist European countries between 1991 and 2010. In South American countries, a significant association has been identified since 1990 using multivariate regression analysis,21 that is, when and where bed numbers were more reduced, the prison population tended to increase more.

Against this background, the present study used longitudinal data from 11 European countries to assess whether ongoing trends in institutional care since 1990 are consistent with the notion of re-institutionalisation and in what way changes in psychiatric bed numbers are associated with changes in other forms of institutional care, including the prison population.

Methods

Sample

We attempted to identify data on institutional mental healthcare in European countries, excluding the post-communist countries as their data had already been reported and analysed in a previous study. The selection of countries was largely due to convenience as it was driven by the availability of sufficiently reliable data. We included 11 European countries from different regions: Northern Europe, including the British Isles (UK and Ireland) and Scandinavia (Denmark); Central Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands); and Southern Europe (Spain and Italy). Although all of the included countries underwent major mental health reforms with de-institutionalisation since the 1950s, they represent different traditions of mental healthcare, different social and judicial systems, and healthcare systems with different funding arrangements and organisations.8

Data sources and variables

Data on psychiatric hospital bed numbers were retrieved from the European Health for All Database (HFA-DB). According to the HFA-DB, ‘psychiatric hospital beds’ are defined as hospital beds accommodating patients with mental health problems, a definition harmonised with EUROSTAT and OECD in 2006. Prison population data were extracted from the statistical office of the European Union (EUROSTAT). According to EUROSTAT, ‘prison population’ is defined as the total number of adult and juvenile prisoners (including pretrial detainees) at 1 September (or nearest available date) of a given year. The numbers of forensic beds, including all forms of forensic inpatient care and protected housing places, were obtained from national annual reports and websites of Ministries of Health, Ministries of Social Welfare, Ministries of Justice and National Statistical Offices of the studied countries. Protected housing was used as an umbrella term for all forms of supported housing, including residential care. Authors also sought help from collaborators in several countries to access appropriate sources of information. Where the number of forensic beds was not available, the number of forensic treatment cases was used as proxy if available. Similarly, where numbers of protected housing places were unavailable, the number of residents in supported places was used if available.

Since macroeconomic factors have been suggested to influence the number of psychiatric hospital beds,18 21 22 we also obtained data on the gross domestic product (GDP). Data on GDP per capita were obtained from the World Bank (http://www.worldbank.org). For GDP per capita, data in constant 2005 U.S. dollars were used to exclude any effect of fluctuating exchange rates.

Statistical analysis

The official data were first set up as panel data where a given sample of individuals was followed over time23 (ie, repeated observations from 11 countries observed at 22 different time periods) and analysed using STATA statistical software V.12. For all analyses, p<0·05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

First, descriptive statistics (time series graphs and overall magnitude of changes) were generated to explore the development of alternative institutional care and prison populations over time. Next, in order to assess the associations between psychiatric hospital beds and other forms of institutional care, that is, forensic beds, places in protected housing and prison populations, panel data linear regression models were used. For all variables, numbers per 100 000 inhabitants rather than absolute figures were used in order to avoid a bias arising from differences in population size and growth between the countries.

In all analyses of associations, the number of psychiatric hospital beds was used as the independent variable and other forms of care as the dependent variable. This was to test whether changes in psychiatric hospital bed numbers may have influenced the provision of other institutions, which for the association of psychiatric beds with the prison populations reflects the hypothesis of Penrose.

We first computed univariate fixed effects analyses individually with prison populations, forensic beds and protected housing places as dependent variables and psychiatric hospital beds as independent variables. To explore the potential association between hospital beds and prison populations further, we then conducted multivariate regression analyses, in which an independent variable (eg, GDP) was added separately as a potential covariate.

Fixed effects models were used to control for all time-invariant differences between the countries in the sample, and the resulting estimation is not biased by omitted time-invariant characteristics.24 Furthermore, robust sandwich estimators were used because they produce estimates of the SEs that are robust to the detected heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in our panel data.

Owing to the long coverage of data over the 22-year period, time units were also accounted for in addition to country-specific effects. To cross-check the appropriateness of time-fixed effects, a joint test was conducted across the multivariate analyses.25 Time fixed effects control for omitted variables that vary over time but are constant over units.26 In this case, the joint test showed that time fixed effects are needed, so that these analyses were also conducted with joint fixed effects (country and year).

Results

Trends in psychiatric beds, forensic beds, residential supported places and prison populations

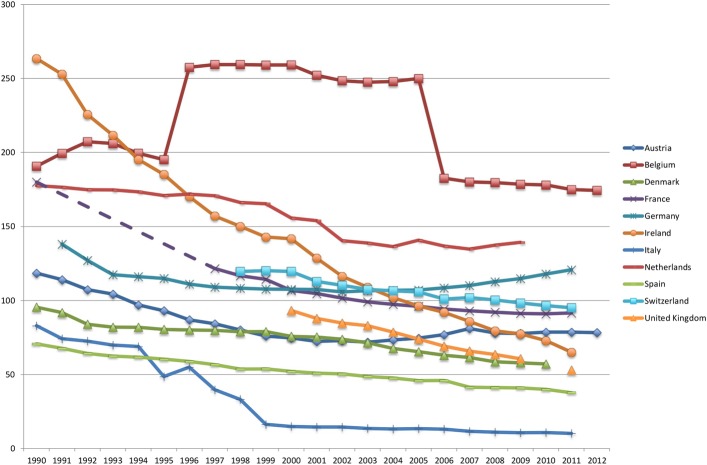

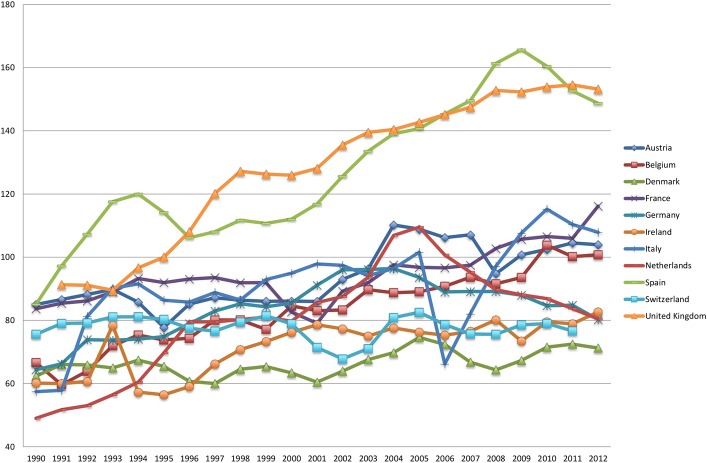

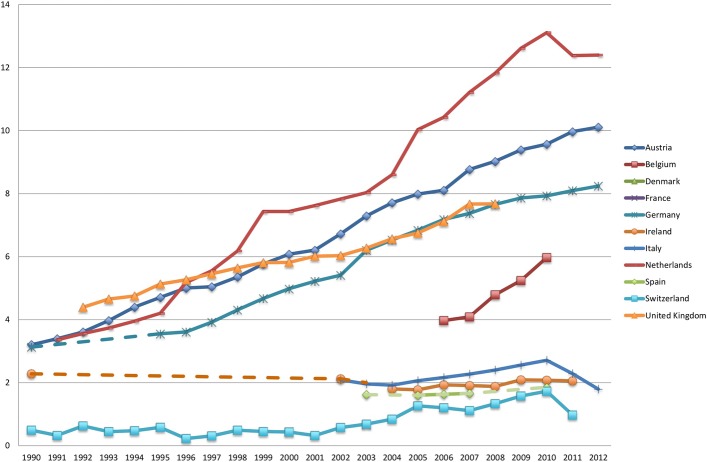

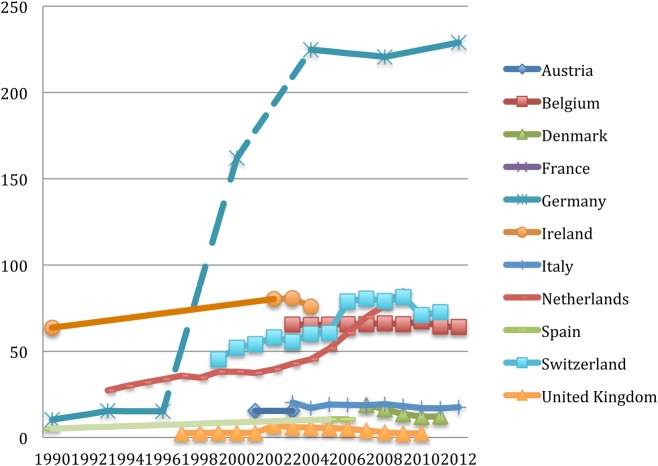

Data on psychiatric hospital beds and prison populations were obtained in all 11 countries. As shown in figure 1, the overall number of psychiatric hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants fell in all countries over time. At the same time, the prison population increased in all countries (figure 2). The number of forensic beds per 100 000 inhabitants rose in almost all countries (figure 3), while changes in protected housing were inconsistent across countries (figure 4). For instance, there was a steady increase in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, while data show a reduction in Denmark, Italy and Ireland. Dashed lines in figures indicate extrapolation of missing data between years.

Figure 1.

Psychiatric hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants from 1990 to 2012.

Figure 2.

Prison population per 100 000 inhabitants from 1990 to 2012.

Figure 3.

Forensic beds per 100 000 inhabitants from 1990 to 2012.

Figure 4.

Places in protecting housing per 100 000 inhabitants from 1990 to 2012.

The magnitude of changes varies across countries. When analysing average changes over time in different forms of institutional care, the averages refer only to those countries for which data for the given form of institutional care are available, which varies.

From 1990 to 2000, the average decrease of psychiatric hospital beds was 42.5 beds per 100 000 inhabitants, and from 2000 to 2012 it was 22.44. During the same two periods, prison populations rose by an average of 21.82 and 17.05, respectively. Forensic beds rose by an average of 0.49 between 1990 and 2000 and of 0.76 between 2000 and 2012. For protected housing places, there were too few data for an estimate of average changes between 1990 and 2000. For the period from 2000 to 2012, there was an average increase of 5.03 places per 100 000 inhabitants, although some countries showed a reduction during this time.

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses

Table 1 shows the results of associations between psychiatric hospital beds and other forms of institutional care.

Table 1.

Results of univariate regression using psychiatric beds per 100 000 inhabitants as independent variables (with country fixed effects)

| N (observations) | Fixed effects | p Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||||

| 1. Prison population per 100 000 inhabitants | 215 | −0.216 | 0.021 | −0.392 to −0.040 |

| 2. Forensic beds per 100 000 inhabitants | 125 | −0.033 | 0.316 | −0.104 to 0.037 |

| 3. Residential beds per 100 000 inhabitants | 76 | −0.184 | 0.108 | −0.417 to 0.049 |

The number of observations in each model varied (table 1), as data were not available for all countries and years for the different main study variables, in particular data on forensic beds and protected housing places. The number of available data points for these two variables is lower than that for the variables where data were available from international sources. The univariate fixed effects regression analyses showed a significant negative association between psychiatric hospital beds and prison populations, and non-significant coefficients for the associations with forensic beds and protected housing places.

The significant association between psychiatric hospital beds and prison populations was then further explored in multivariate regressions adjusting for overall time effects and potential covariates to account for spurious relationship. There was a positive significant relationship between GDP and prison populations, that is, a higher GDP was linked with a larger prison population (0.001; 95% CI 0.00001 to 0.0027; p=0.032). When GDP was included as a covariate in the multivariate regression analysis, the association between bed numbers and prison population was no longer significant (−0.024; 95% CI −0.189 to 0.141; p=0.756). The same happened when year fixed effects were considered: bed numbers and prison population were not significantly associated anymore (−0.003; 95% CI −0.123 to 0.118; p=0.958).

Discussion

Main findings

The provision of institutional forms of mental healthcare has changed in Western Europe since 1990 and the changes continue to appear. The number of psychiatric hospital beds has been falling substantially. At the same time, the numbers of forensic beds and prison populations have increased, while changes in protected housing have been inconsistent across countries with a tendency to increase too.

Overall, the number of reduced psychiatric hospitals is larger than the total number of additional places in other forms of institutional care combined. The precise figures vary between countries, but the overall difference is substantial if one assumes that only a proportion of additional prisoners are likely to have a mental disorder. If one excludes the prison populations from this analysis, because it is debatable as to whether prisons can be seen as forms of care, the number of reduced beds exceeds the additionally established places even more clearly. So the total number of institutional places in mental healthcare has rather decreased, and this applies, although to a different extent, to the period from 1990 to 2000 and the following period until 2012. However, according to these findings, there has been further de-institutionalisation in terms of psychiatric hospital beds in addition to an ongoing trend towards re-institutionalisation, namely forensic beds and prison populations.

The data of this study cannot reveal the historical and societal drivers behind the decrease of psychiatric beds and increase of prison populations. The reduction of hospital beds and the increase of other forms of institutional care happened over the same period of time, and both phenomena are likely to be linked as part of overall historical changes in European societies. Societal processes leading to an increase of prison populations are complex. Data as presented in this study cannot identify the real influence of anticipated or experienced bed closures within these processes. However, the data did allow one to explore a quantitative association of the extent of the two phenomena, that is, whether there were fewer beds when and where there were overall more prisoners. We did find such an association, which was statistically significant. However, once adjusted for overall time trends (years as fixed effect) or the overall economic activity of a country (GDP), the correlation was no longer significant. Thus, falling bed numbers and rising prison populations appear to go together, but they are not necessarily causally linked. Wider political and social changes in a society, as reflected by the GDP and potentially other indicators, are the drivers for the changes, and trends other than changes in bed numbers may explain the extent of the increase of prison populations in Western Europe.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest longitudinal study examining the association between different types of institutional mental healthcare, including prisons populations, in Western Europe over a period of 22 years. This study included countries from different regions within Western Europe and used what are arguably the best available data. The study included forensic beds and protected housing places to have a more comprehensive picture of institutional care as far as such institutions are defined by bricks and mortar. In the analysis of associations, we considered non-specific time effects and GDP as a potential covariate. The association between bed numbers and prison population was no longer significant, representing other important societal time trends.

The study also has several major limitations; thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. First, the accuracy of some data remains questionable. We tried and took the most reliable data by cross-checking between reports. Yet some of the data had been collected for administrative purposes rather than for research, and definitions and reporting procedures were inconsistent. In particular, figures for forensic beds and protected housing places referred to varying and sometimes vague definitions. Second, we included only 11 countries, and for some forms of institutional care, in particular protected housing, the number was even smaller. As a result, the overall number of observations is rather small for a panel data analysis, and too small to conduct more complex analyses such as a co-integration analysis as a method for identifying influences in time series.

Third, comparisons of absolute numbers across countries should be carried out only with great caution, as the definitions of settings and samples vary significantly. Within each country, however, definitions are likely to have been consistent so that changes over time can be interpreted with more confidence.

Finally, the data are only total figures of patients in each type of institution without any breakdown of diagnosis or other patient characteristics. These total figures cannot reveal whether there is ongoing de-institutionalisation or re-institutionalisation for specific patient groups such as those with severe and chronic disorders.

Comparisons against the literature

Comparisons against findings in other regions in the world and other historical contexts are problematic. Mundt et al21 have provided data from South American countries since 1990. They suggested an association between psychiatric hospital beds and the prison population in line with the Penrose hypothesis, although, unlike Penrose, they explicitly did not assume a direct causal relationship. However, the numbers involved were very different from those in Europe. While in South America there were five more prisoners since 1990 for every reduced psychiatric bed, in Western Europe there were more beds reduced than additional prison places established. A similar study of changes of institutional care in post-communist countries in Eastern Europe analysed data from a period of drastic reductions of the prison population in some countries during that time,20 a historically rather unusual phenomenon.

It appears questionable as to whether generalised hypotheses—like the Penrose hypothesis—can be applied across so different contexts.

The analysis of mere numbers of places in institutions does not show the characteristics of people in them. In 1939, Penrose had patients with severe mental illness in mind, who would be either in a hospital or in a prison. Recent studies indeed show an overlap of people who over time can be in a type of revolving door between prison and psychiatric hospital care.27 Yet the predominant diagnosis of these people is a substance abuse disorder, sometimes but not always linked with a severe mental illness.28–30 People with severe mental illness are the dominant group in different forms of protected housing and in forensic beds,31 while the clientele of inpatient care may vary more depending on the number of beds available and the organisation of care in each country. Since there has been a tendency for shorter lengths of stay of inpatient care since 1990, the reduced bed number does not mean that the number of patients who get hospitalised at some point of time has similarly decreased. In all institutions, the length of stay is essential to estimate the number of people who are affected over time.

Conclusion

The trends towards decreasing psychiatric bed numbers and overall increasing forms of other forms of institutions for people with mental disorders in Western Europe—first described in 2005—appear to continue, although the drivers for these changes and the precise relationships between them remain poorly understood.

The places in institutional mental healthcare may reflect the approach of a society to people with mental disorders, and certainly involve substantial costs to the health, social and judicial systems. This study underlines the need for more complete and reliable data from more countries. Better data would allow more reliable time series analyses. However, statistical analyses of places in institutions alone will not provide conclusive evidence on the causes for changes, and various potential economic, social and political drives may have to be analysed as potential drivers for changes in different forms of institutions.

Data are needed on the number of places in institutions, as well as on the precise characteristics and histories of people with mental disorders in these institutions. While routine data are largely available for the characteristics of patients in hospital beds, less is known about people with mental disorders in prisons10 13 14 27 29 30 and even less about patients in protected housing services.31 32 Most importantly, studies of long-term pathways of people moving between these institutions are required to understand their potential interplay. The aim of such wider research should be to explore how the institutions included in this study, as well as other community-based and outpatient services, are linked and influence each other. This will require complex analyses of whole mental healthcare systems, which an increasing availability of comprehensive routine data may allow in the future.33

Finally, evidence is required on how effective and cost-effective care in psychiatric hospitals, in forensic beds and in protected housing for different patient groups is, for example, as compared to outpatient care, so that policies and funding for institutional care can be based on evidence about their costs and benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the collaborators in the different countries for their time and support with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study concept and design were developed by WSC and SP in collaboration. WSC performed the literature search, gathered the data, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. The manuscript was then further developed and edited by SP. Both authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved of the final version.

Funding: The study was funded by the East London NHS Foundation Trust in the context of a Ph.D. studentship at Queen Mary University of London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full data set is available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Thornicroft G, Bebbington P. Deinstitutionalisation—from hospital closure to service development. Br J Psychiatry 1989;155:739–53. 10.1192/bjp.155.6.739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow WS, Priebe S. Understanding psychiatric institutionalization: a conceptual review. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:169 10.1186/1471-244X-13-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb HR, Bachrach LL. Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1039–45. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muijen M. Focus on mental health care reforms in Europe. Mental health services in Europe: an overview. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:479–82. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhoury W, Priebe S. The process of deinstitutionalization: an international overview. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15:187–92. 10.1097/00001504-200203000-00011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakhoury W, Priebe S. Deinstitutionalization and reinstitutionalization: major changes in the provision of mental healthcare. Psychiatry 2007;6:313–16. 10.1016/j.mppsy.2007.05.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Mental health ten years on: progress on mental health care reform. DH, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Priebe S, Badesconyi A, Fioritti A et al. Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison of data on service provision from six European countries. BMJ 2005;330:123–6. 10.1136/bmj.38296.611215.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Priebe S, Frottier P, Gaddini A et al. Mental health care institutions in nine European countries, 2002 to 2006. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:570–3. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 2002;359:545–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konard N. Prisons as new asylums. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15:583–7. 10.1097/00001504-200211000-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. The shift of psychiatric inpatient care from hospitals to jails and prisons. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2005;33:529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dressing H, Kief C, Salize HJ. Prisoners with mental disorders in Europe. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:88 10.1192/bjp.194.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazel S, Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:364–73. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penrose LS. Mental disease and crime: outline of a comparative study of European statistics. Br J Med Psychol 1939;18:1–15. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1939.tb00704.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly BD. Penrose's law in Ireland: an ecological analysis of psychiatric inpatients and prisoners. Ir Med J. 2007;100:373–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartvig P, Kjelsberg E. Penrose's Law revisited: the relationship between mental institution beds, prison population and crime rate. Nord J Psychiatry 2009;63:51–6. 10.1080/08039480802298697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Large MM, Nielssen O. The Penrose hypothesis in 2004: patient and prisoner numbers are positively correlated in low-and-middle income countries but are unrelated in high-income countries. Psychol Psychother 2009;82:113–19. 10.1348/147608308X320099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prins SJ. Does transinstitutionalization explain the overrepresentation of people with serious mental illnesses in the criminal justice system? Community Ment Health J 2011;47:716–22. 10.1007/s10597-011-9420-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mundt AP, Frančišković T, Gurovich I et al. Changes in the provision of institutionalized mental health care in post-communist countries. PLoS ONE 2012;7(6):e38490 10.1371/journal.pone.0038490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mundt AP, Chow WS, Arduino M et al. Psychiatric hospital beds and prison populations in South America since 1990: does the Penrose hypothesis apply? JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:112–18.13 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceccherini-Nelli A, Priebe S. Economic factors and psychiatric hospital beds—an analysis of historical trends. Int J Soc Econ 2007;34:788–810. 10.1108/03068290710826396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao C. Analysis of panel data. 2nd edn Cambridge Universirty Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene W. Econometric analysis. 5th edn Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wooldridge JM. Econometric data of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mundt AP, Kastner S, Mir J et al. Did female prisoners with mental disorders receive psychiatric treatment before imprisonment? BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:5 10.1186/s12888-015-0387-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunn J. Future directions for treatment in forensic psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:332–8. 10.1192/bjp.176.4.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrell M, Boys A, Bebbington P et al. Psychosis and drug dependence: results from a national survey of prisoners. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:393–8. 10.1192/bjp.181.5.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction 2006;101:181–91. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Priebe S, Saidi M, Want A et al. Housing services for people with mental disorders in England: patient characteristics, care provision and costs. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 2009;44:805–14. 10.1007/s00127-009-0001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Girolomo G, Picardi A, Micciolo R et al. Residential care in Italy. National survey on non-hospital facilities. Br J Psychiatr 2002;181:220–5. 10.1192/bjp.181.3.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munk-Jørgensen P. Has deinstitutionalization gone too far? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;249:136–43. 10.1007/s004060050078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]