Abstract

While we may be comfortable with an allopathic approach to male infertility, we are also responsible for knowledge about lifestyle modifications and holistic, complementary, and alternative therapies that are used by many of our patients. This paper provides an evidence-based review separating fact from fiction for several of these therapies. There is sufficient literature to support weight reduction by diet and exercise, smoking cessation, and alcohol moderation. Supplements that have demonstrated positive effects on male fertility on small randomized controlled trial (RCT) include aescin, coenzyme Q10, glutathione, Korean red ginseng, L-carnitine, nigella sativa, omega-3, selenium, a combination of zinc and folate, and the Menevit antioxidant. There is no support for the use of Vitamin C, Vitamin E, or saffron. The data for Chinese herbal medications, acupuncture, mind-body practice, scrotal cooling, and faith-based healing are sparse or inconclusive.

Keywords: alcohol, antioxidants, caffeine, faith-based healing, male infertility, obesity, scrotal cooling, sperm, tobacco, traditional Chinese medicine

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing interest in the United States and worldwide for modification of lifestyle factors, as well as holistic, complementary, and alternative approaches to treat male infertility. As practitioners of allopathic medicine, it is our duty to not only be aware of what our patients are trying outside of our office, but to be proactive in guiding couples through which holistic, complementary, and alternative therapies are valid and which are worthless. Obesity, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol intake have all been associated with subfertility, but how much is too much? Will weight loss, smoking cessation, and alcohol moderation improve fertility in the subfertile man? Is caffeine good or bad for male fertility? Nutritional supplements, herbal medications, acupuncture, mind-body practice, scrotal cooling, and faith-based treatments are increasingly utilized in addition to, or instead of, conventional allopathic approaches. Do any of these approaches truly improve male infertility? This paper provides an evidence-based review of lifestyle factors, holistic, complementary, and alternative therapies as they relate to male infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A preliminary search of the MEDLINE and Cochrane databases was performed using the following keywords: “complementary medicine,” “alternative medicine,” “obesity,” “smoking,” “alcohol,” “caffeine,” “supplements,” “herbal medicine,” “Traditional Chinese Medicine,” “acupuncture,” “acupressure,” “yoga,” “tai chi,” “qigong,” “chiropractic,” “body work,” “scrotal cooling,” “scrotal hypothermia,” “prayer,” “faith healing,” and “spiritualism” cross-referenced with “male infertility” and “sperm.” Nonhuman studies were excluded. The results and their bibliographies were analyzed and used to develop a more extensive search of the MEDLINE database. These search results were examined for articles involving obesity and weight loss, smoking and smoking cessation, alcohol and alcohol moderation or abstinence, caffeine intake and caffeine supplementation to cryopreserved sperm, herbs and supplements, Traditional Chinese Medicine, acupuncture, mind-body practice, scrotal cooling, spiritualism, and their therapeutic use or effects in male infertility. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were included based on the use of objective measures, articles written in the English language, and the inclusion of clear published clinical outcomes. Observational and quasi-experimental studies and reviews were included when RCTs were not identified for the specific therapeutic modality.

RESULTS

Modifiable lifestyle factors

Obesity

Obesity is associated with lower serum testosterone and LH,1 elevated rates of oligospermia or azoospemia,2 and decreased ejaculate volume, sperm concentration, and total sperm count.3 The relationship between obesity and male infertility is likely multifactorial. Hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses that regulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis depend on appropriate caloric and nutritional intake. When there is an energy imbalance, whether inadequate or excessive, disruption in GnRH pulses causes impairments in semen quality. Excess adipose tissue also results in increased conversion of testosterone to estradiol, which may lead to secondary hypogonadism through HPG axis suppression.4 Obesity may also increase endorphins that blunt the GnRH pulse.5 Additionally, excess scrotal fat has been hypothesized to elevate scrotal temperatures resulting in impaired sperm quality.6

Two case series investigated if bariatric surgery would improve semen parameters in obese men. In a case series of two patients who underwent bariatric surgery, one patient experienced increased sperm aneuploidy with a decline in sperm concentration, motility, and morphology, while the other became azoospermic.7 In a case series of three patients who underwent bariatric surgery, all developed extreme oligoasthenoteratospermia.8 This seemingly paradoxical worsening of semen quality with surgical weight loss may be explained by nutritional deficiencies from sudden weight loss disrupting normal pulsatile GnRH secretion.4 In a cohort study of 43 men with BMI >33, BMI was inversely associated with sperm concentration, morphology, motility, and testosterone. Weight loss through a 14-week residential weight loss program was associated with an increase in total sperm count, semen volume, and testosterone.9 While both case series of bariatric surgery demonstrated impairment of sperm production with rapid weight loss and sudden decrease in caloric intake, a lifestyle-based program with gradual weight loss through exercise and a progressive decrease in caloric intake led to improvement in sperm parameters.

There is no RCT to assess the effect of obesity or weight loss in obese men on male infertility. However, evidence suggests obesity may lower sperm parameters and testosterone. These effects may be reversible with gradual weight loss through diet and exercise, but not with bariatric surgery. Using diet and exercise to achieve and maintain normal BMI is recommended for obese men with male factor infertility.

Tobacco

A systematic review of male smokers identified no consistent effect on sperm quality in 21 of 21 studies and no effect on chemical pregnancy or live birth rate in 4 of 4 studies.10 However, since this review was published nearly 20 years ago, multiple recent studies have demonstrated contradictory findings. Smoking has been associated with lower sperm concentration,11 impaired sperm motility and morphology,12 and increased frequencies of sperm aneuploidy.13 Use of chewing tobacco also has a dose-dependent negative effect on sperm count, motility, morphology, and viability.14 The Ontario Farm Family Health Study, a retrospective cohort study on 2607 planned pregnancies, identified that male smoking reduced fecundability (fecundability ratio 0.8, 95% CI: 0.81–0.95).15 Smoking appears to increase levels of spermatotoxic benzo(a)pyrene and cause oxidative injury to sperm DNA. Benzo(a)pyrene is a highly mutagenic carcinogen. Compared to nonsmokers, the sperm of smokers show high levels of benzo(a)pyrene binding to DNA in sperm.16 Cigarette consumption also lowers serum antioxidant activity (superoxide dismutase, P = 0.01) in a dose-dependent manner.17

Although there are no RCTs demonstrating a negative impact on male fertility, The American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) prudently discourages smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke in both men and women attempting to conceive.18

Alcohol

Two studies suggest that moderate alcohol consumption does not impair semen parameters.15,19 Several other studies indicate alcohol consumption is associated with deterioration of sperm parameters and testicular pathology in a dose-dependent fashion.12,20,21,22 One study suggests that even one alcoholic drink a day may negatively impact miscarriage rates and live birth rates associated with in vitro fertilization (IVF).23

A case report demonstrated progressive alcohol-induced sperm alterations during heavy chronic alcohol intoxication (165 g alcohol daily for 10 years). The initial finding was teratospermia (August 2002), followed by oligoasthenoteratospermia (March 2005), cryptozoospermia (June 2007) and ultimately azoospermia (November 2007). A testicular biopsy (December 2007) revealed maturation arrest of the germinal cells at the pachytene stage with no mature sperm cells. Once alcohol withdrawal was achieved (January 2008), normospermia occurred within 3 months (April 2008).24

The effect of alcohol and alcohol sobriety on male infertility has not been assessed with a RCT. From the available literature, evidence suggests a dose- and duration-dependent effect of alcohol on male infertility. While an adverse effect on sperm parameters was not detectable in men with limited alcohol use, progressive deterioration in semen quality was demonstrated in several studies. Habitual alcohol abuse is also associated with hypogonadism which may arise from both primary testicular failure and an inhibition of gonadotropins. The deleterious effects of alcohol on male fertility may be reversible with alcohol abstinence. Even when semen parameters are not affected, alcohol use is associated with higher miscarriages and lower birth rates with IVF. The evidence is sufficient to recommend minimizing alcohol consumption for men.

Caffeine

The effect of caffeine on male fertility has been studied both as dietary intake and as an in vitro supplement to sperm. High caffeine consumption (>6 cups coffee daily) was associated with increased sperm motility in one study,25 while three other studies demonstrated no effect of caffeine on sperm parameters, including a study that compared low (≤100 mg caffeine daily) to very high caffeine intake (>800 mg caffeine daily).26,27,28 In a prospective IVF study, caffeine intake did not affect oocyte fertilization, pregnancy, miscarriage, or live birth. However, the odds of multiple gestations increased by 3.0 for each 100 mg per day of caffeine intake by men during the week of the initial clinic visit or during the week before sperm collection.27

In a number of studies, the addition of caffeine to medium increased the motility of both fresh29 and cryopreserved sperm.30,31,32,33,34 The effect of in vitro caffeine supplementation on other sperm parameters and fertility outcomes were inconsistent. Caffeine caused injury to the sperm head in one study,35 yet another study identified no morphological changes.36 A decrease in fertilization and embryonic development was noted at high concentrations of caffeine in the culture medium,34 while other studies showed improvement in cervical mucus penetration30 and pregnancy rates with IUI (intrauterine insemination) for subfertile men from the addition of caffeine.36 An assessment of Sertoli cells cultured with increasing doses of caffeine found that low doses of caffeine (5 μmol l−1) stimulated lactate production which can promote germ cell survival. Moderate doses (50 μmol l−1) increased expression of glucose transporters. However, the antioxidant capacity of Sertoli cells decreased in a dose-dependent manner with caffeine. Sertoli cells exposed to high doses (500 μmol l−1) demonstrated a pro-oxidant potential with an increase of oxidative damage.37

While there is no RCT evaluating the effect of caffeine on male fertility and the existing studies on caffeine are inconsistent, moderate consumption of caffeine appears to be safe for male reproductive health. There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against in vitro caffeine supplementation.

Nonprescription medications and supplements

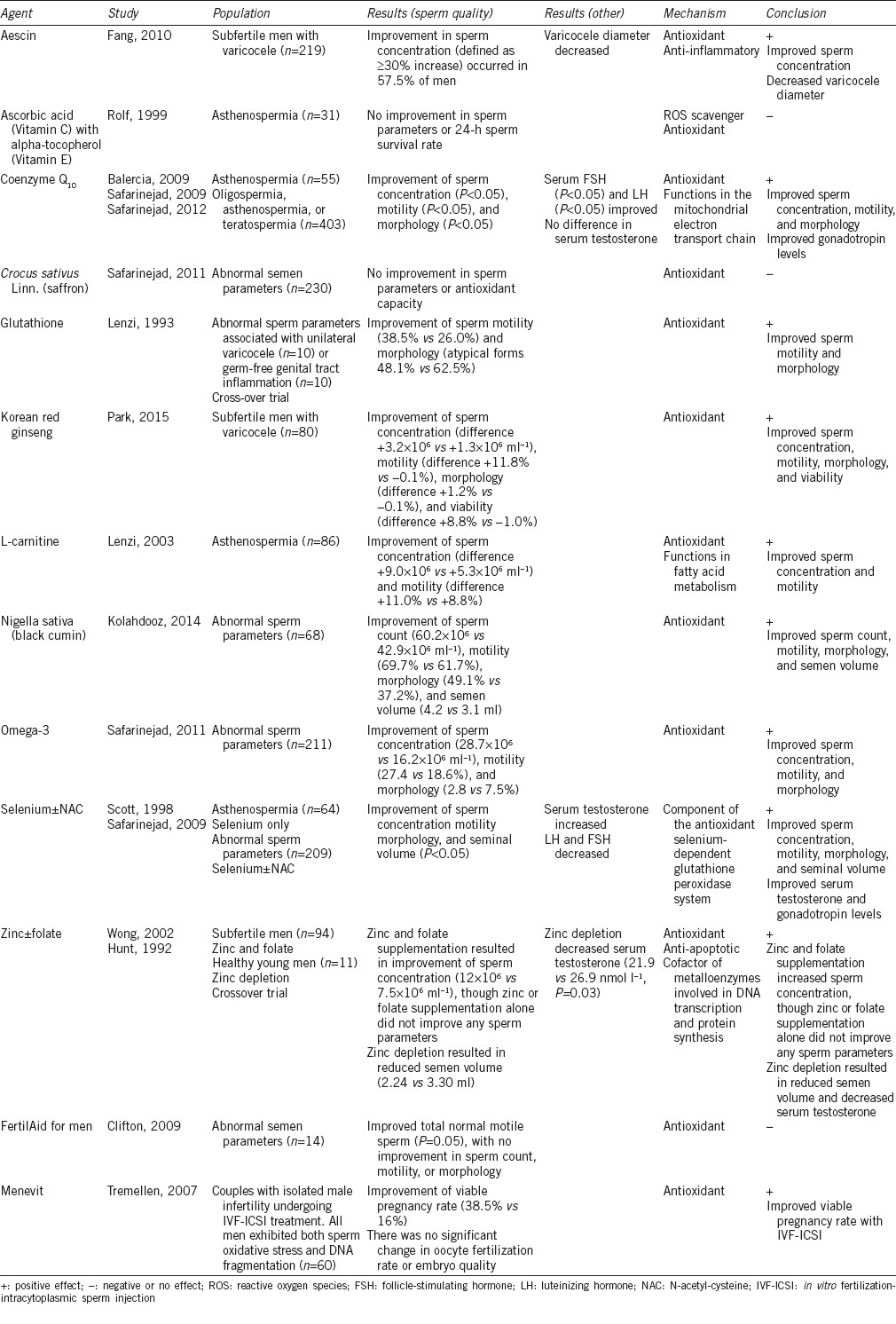

While the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate nutritional supplements, these have become a mainstay of infertility treatment. The following section reviews the literature on nonprescription medications and supplements. Given the vast number of supplements marketed for male infertility, this section is limited to supplements that have been investigated with a RCT. A summary of these supplementations is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes and conclusions from nonprescription medications and supplements

Individual nonprescription medications and supplements

Aescin (horse chestnut seed extract) is a mixture of saponins with antioxidant, anti-edematous, and anti-inflammatory properties.38,39,40 In a study of 219 men with varicocele-associated infertility, a 2-month course of aescin (30 mg twice a day) was compared with a control of Vitamin E, pentoxifylline, and clomiphene. Improvement in sperm concentration (defined as ≥30% increase) was more common in the aescin group (57.5% vs 38.5%, P < 0.05). Varicocele size also decreased with aescin, though the effective rate was more pronounced in mild (41.7%, P > 0.05) and moderate (64.4%, P < 0.05) varicoceles than severe varicoceles (20%).41

Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) is a reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger that may protect sperm against oxidative DNA damage.42 Alpha-tocopherol (Vitamin E) is also an antioxidant. Levels of Vitamin E in sperm have been positively correlated with sperm motility (P < 0.001).43 In a study of 31 infertile men with asthenospermia, an 8-week course of high dose Vitamins C (1000 mg daily) and E (800 mg daily) was compared to placebo. Combined high dose Vitamins C and E did not improve semen parameters or the 24 h sperm survival rate.44

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is an antioxidant that may also contribute to sperm production and quality through its function in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.45 In a study of 55 men with asthenospermia, a 6-month course of CoQ10 (200 mg daily) improved sperm motility (39% vs 33%, P < 0.0001) compared with placebo. Motility returned to baseline after stopping CoQ10 for 3 months.46 Another study assessed the effects of a 6-month course of CoQ10 (200 mg daily) on 191 men with oligospermia, asthenospermia, or teratospermia. Those given CoQ10 had increased sperm concentration (28.7 × 106 vs 16.8 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.005), motility (35.8% vs 25.4%, P = 0.008), and morphology (17.6% vs 14.8%, P = 0.01), compared to placebo. Serum FSH (9.6 vs 16.4 IU l−1, P = 0.02) and LH (8.2 vs 13.1 IU l−1, P = 0.03) decreased. There was no significant difference in serum testosterone.47 Twenty-six weeks of a higher dose of CoQ10 (300 mg daily) in a different group of 212 men with oligospermia, asthenospermia, or teratospermia, similarly improved sperm concentration (26.4 × 106 vs 20.8 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.01), motility (27.6% vs 23.1%, P = 0.04), and morphology (9.6% vs 7.8%, P = 0.04), while serum FSH (10.7 vs 16.8 IU l−1, P = 0.03) and LH (8.8 vs 12.6 IU l−1, P = 0.03) decreased.48

Crocus sativus Linn. (saffron) is a spice containing antioxidant rich carotenoids that scavenge free radicals. A study of 230 infertile men with abnormal semen parameters demonstrated no improvement in sperm concentration, motility, or morphology after 26 weeks of saffron (60 mg daily) compared to placebo. Additionally, saffron failed to improve seminal plasma antioxidant capacity.49

Glutathione is an intracellular antioxidant found in every cell of the human body.50 Glutathione therapy (600 mg IM every other day) for 2 months was assessed in a cross-over trial of 20 infertile men with abnormal sperm parameters associated with unilateral varicocele (n = 10) or germ-free genital tract inflammation (n = 10). Glutathione supplementation improved sperm motility (38.5% vs 26.0%, P < 0.01) and morphology (atypical forms 48.1% vs 62.5%, P < 0.001) after 1 month of treatment. The benefits did not persist when the glutathione was stopped.51

Korean red ginseng (KRG) is composed of multiple ginsenosides, a class of natural product steroid glycosides and triterpene saponins, some of which have antioxidant properties.52 A total of 80 infertile men with varicocele were randomized to placebo, KRG (1.5 g daily), varicocelectomy with placebo, or varicocelectomy with KRG. Semen analysis was obtained in each treatment arm after 12 weeks. Compared to placebo, treatment with KRG improved sperm concentration (difference +3.2 × 106 vs +1.3 × 106 ml−1, P < 0.05), motility (difference +11.8% vs −0.1%, P < 0.01), morphology (difference +1.2% vs −0.1%, P < 0.01), and viability (difference +8.8% vs −1.0%, P < 0.05).53

L-carnitine is a quaternary ammonium compound required for fatty acid metabolism that also has antioxidant effects.54,55 In a randomized trial of 86 infertile men with asthenospermia, a 2-month supplementation with L-carnitine (2 g daily) improved sperm motility (difference +11.0% vs +8.8%, P = 0.04) and concentration (difference +9.0 × 106 vs +5.3 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.01) compared to placebo.56

Nigella sativa (black cumin) is a medicinal plant with antioxidant properties. In a study of 68 infertile men with abnormal semen parameters, a 2-month course of black cumin oil (2.5 ml twice a day) improved sperm count (60.2 × 106 vs 42.9 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.01), motility (69.7% vs 61.7%, P = 0.02), morphology (49.1% vs 37.2%, P < 0.01), and semen volume (4.2 vs 3.1 ml, P < 0.01) compared to placebo.57

Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA, EPA and ALA) are essential to normal human physiology. They may act as antioxidants. Sperm from asthenospermic males have lower levels of DHA in the sperm membrane compared to those from fertile men.58 Seminal plasma EPA and DHA concentrations were positively correlated with seminal plasma superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase-like activity (P = 0.001), both markers of anti-oxidant activity.59 In a study of 211 infertile men with abnormal semen parameters, omega-3 supplementation (515.2 mg EPA and 331.2 mg DHA daily) for 28 weeks improved sperm concentration (28.7 × 106 vs 16.2 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.001), motility (27.4% vs 18.6%, P = 0.002), and morphology (12.8% vs 7.5%, P = 0.002).

Selenium is a mineral that could provide beneficial effects to sperm as a component of the selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase system.60 In a study of 64 asthenospermic men, selenium supplementation to normal amounts (100 μg daily) for 3 months improved sperm motility (28.2% vs 20.1%, P = 0.04) compared to placebo.61 Twenty-six weeks of high dose selenium supplementation (200 μg daily) in 105 subfertile men with abnormal sperm parameters improved sperm concentration (27.6 × 106 vs 22.4 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.03), motility (26.1% vs 22.1%, P = 0.03), morphology (9.2% vs 7.2%, P = 0.03), and seminal volume (3.2 vs 2.7 ml, P = 0.02). The addition of N-acetyl-cysteine (600 mg daily), a free radical scavenger, to high dose selenium (200 μg daily) resulted in similar beneficial effects in sperm concentration (32.1 × 106 vs 21.6 × 106 ml−1, P = 0.01), motility (29.2% vs 22.8%, P = 0.02), morphology (9.3% vs 7.2%, P = 0.03), and ejaculate volume (3.4 vs 2.7 ml, P = 0.03) in a separate cohort of 104 subfertile men. In both selenium and selenium + N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) supplementation cohorts, serum testosterone (20.1 vs 17.4 nmol l−1, P = 0.04; 20.9 vs 17.8 nmol l−1, P = 0.03) rose, while LH (3.6 vs 4.1 IU l−1, P = 0.04; 3.7 vs 4.4 IU l−1, P = 0.04) and FSH (2.1 vs 2.8 IU l−1, P = 0.04; 1.8 vs 2.6 IU l−1, P = 0.03) fell, compared to placebo. Following cessation of selenium ± NAC supplementation, all semen parameters and serum hormone levels returned to pretreatment levels after two spermatogenesis cycles (26 weeks).62

Zinc is a micronutrient that may also promote sperm quality through its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties.63,64 Zinc acts as a cofactor of metalloenzymes involved in DNA transcription and protein synthesis critical to spermatogenesis.65 In a crossover dietary study of 11 healthy young male volunteers (mean age 28 years), severe zinc depletion resulted in reduced semen volume (2.24 vs 3.30 ml, P = 0.03) and decreased serum testosterone (21.9 vs 26.9 nmol l−1, P = 0.03), compared to normal zinc consumption.66 In another study of 94 subfertile men, the combination of zinc and folate supplementation increased sperm concentration (12 × 106 vs 7.5 × 106 ml−1, P < 0.05), though zinc or folate supplementation alone did not improve any sperm parameters compared to placebo.67

Oxidative stress can occur as a consequence of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) or impaired antioxidant defense mechanisms. Although low amounts of ROS are required for critical aspects of sperm function, excessive levels of ROS can negatively impact sperm quality, function, and viability.68,69 Excessive ROS damages sperm nuclear DNA and sperm plasma membrane and has also been associated with decreases in testosterone concentration.69,70 All of the nonprescription medications and supplements reviewed in this section demonstrate antioxidant activity. There is at least some evidence for coenzyme Q10, glutathione, L-carnitine, black cumin, omega-3, selenium ± NAC, and zinc + folate, for the improvement of semen parameters. Aescin and Korean red ginseng may benefit subfertile men with varicocele.

A Cochrane review evaluated the effectiveness and safety of oral supplementation with antioxidants for subfertile male partners in couples seeking fertility assistance. There was low quality evidence that antioxidant supplementation may improve clinical pregnancy rates (OR = 3.43, P < 0.0001) and live birth rates (OR = 4.21, P < 0.0001). There was no evidence of increased risk of miscarriage, but this was uncertain as the evidence was of very low quality. Data were lacking on other adverse effects. There were insufficient data to draw any conclusions from antioxidant versus antioxidant comparison.71

Combination nonprescription medications and supplements

There are two combination male fertility supplements evaluated with a RCT. FertilAid for Men is a combination of antioxidants containing L-carnitine, grape seed extract, Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, selenium, maca root, Asian ginseng, and zinc. Fourteen men with abnormal semen parameters were randomized to either 90-day of FertilAid (n = 8) or placebo (n = 6). In the FertilAid group, total normal motile sperm improved (P = 0.05), with no improvement in sperm count, motility, or morphology.72 Given the small number of men in this study, and the limited impact on sperm parameters, it is difficult to recommend this supplement.

The Menevit antioxidant contains lycopene, Vitamin E, Vitamin C, zinc, selenium, folate, and garlic. The hypothesis that Menevit would reduce oxidative sperm damage resulting in an improvement in embryo quality and pregnancy rates during in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF-ICSI) treatment was tested in 60 couples with isolated male infertility. All men exhibited both sperm oxidative stress (poor sperm morphology, motility, or low membrane integrity) and DNA fragmentation (>25% TUNEL positive). Treatment with Menevit for 3 months before their partner's IVF cycle improved viable pregnancy rate (38.5% vs 16%, P = 0.046), defined as a viable fetus at 13 weeks gestation, compared to placebo. There was no significant change in oocyte fertilization rate or embryo quality.73 The Menevit antioxidant showed an improved viable pregnancy rate, but the study was limited to couples undergoing IVF-ICSI, so benefits can not be extrapolated to couples undergoing timed intercourse or IUI.

Traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used for hundreds of years to treat infertility. The goal of therapy is a balance between reproductive energy (qi), blood, and the yin and yang of internal organs. The kidney and spleen are considered especially important organs for male fertility. The kidney regulates the quality of sperm and the spleen transports nutrients required for sperm production and maturation. TCM employs herbal supplements, acupuncture and mind-body practices to improve fertility parameters.

Chinese herbal medications

Herbal medications are a foundation of TCM for male infertility. Other than ginseng, which was previously described, no RCT was identified for individual herbs or decoctions.

Herbs commonly used in TCM for male infertility have been investigated for endocrine and antioxidant activity. A total of seven herbal decoctions and 37 individual herbs, including all the herbs used in the seven decoctions, were screened in vitro for endocrine and antioxidant activity. The seven decoctions tested exhibited strong (5 decoctions) and weak (two decoctions) anti-estrogenic responses (1.14–13.23 mg and 0.22–0.26 mg tamoxifen equivalents per gram of dried herbs respectively), but not estrogenic, androgenic, or anti-androgenic activities. With regard to antioxidant activity, strong (three decoctions), intermediate (three decoctions), and weak (one decoction) responses were identified (1.02–1.2, 0.72–0.76, 0.44 μg ascorbic acid equivalent per mg dried herbs respectively). None of the 37 individual herbs tested showed androgenic properties while seven showed strong and three showed a weak anti-androgenic response (1.54–66.78 mg and 0.17–0.32 mg flutamide equivalents per gram of dried herb, respectively). Estrogenic responses were present in two herbs (85.3–550 μg estradiol equivalents per gram of dried herb), while 20 showed strong and 10 weak anti-estrogenic activity (1.18–1280.66 mg and 0.06–0.98 mg tamoxifen equivalent per gram of dried herb, respectively). Of the 37 herbs, strong (15 herbs), intermediate (seven herbs), and weak/no (15 herbs) antioxidant activity was detected (ranging 0.91–1.26, 0.6–0.88, 0–0.47 μg ascorbic acid equivalent per mg dried herb, respectively). Herbs exhibiting strong antioxidant activity were Radix Paeoniae Rubrae, Cortex Phellodendri, Cortex Moudan Radicis, Rehmannia Glutinosa Libosch, Fructus Corni Officinalis, Semen Cuscutae, Rhizoma Anemarrhenae Asphodeloidis, Fructus Rubi, Fructus Schisandrae Chinensis, Aurantii Fructus, Acori Graminei Rhizome, Nelumbinis Embryo, Rhizoma Cimicifugae, Pericarpium Citri Reticulate Blanco, and Flos Lonicerae Japonicae.74 Because these are in vitro studies, these findings can not be extrapolated as in vivo data.

Human studies do exist for two popular decoctions: Wuzi Yanzong Wan (Pills for Reproduction) and Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang (Decoction for Generating Sperm). A 3-month course of Wuzi Yanzong Wan in 35 infertile men with either asthenospermia or oligospermia improved sperm concentration (27.1 × 106 vs 14.9 × 106 ml−1, P < 0.01) and motility (50.6% vs 24.6%, P < 0.01) compared to pretreatment sperm parameters. A 3-month course of Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang in a separate cohort of 35 infertile men with either asthenospermia or oligospermia, improved sperm concentration (33.4 × 106 vs 14.8 × 106 ml−1, P < 0.01) and motility (56.7% vs 25.3%, P < 0.01) compared to pretreatment sperm parameters. The improvement in sperm concentration (P < 0.01) and motility (P < 0.01) was superior with Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang compared to Wuzi Yanzong Wan.75

A different formulation of Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang was assessed for an effect on antisperm antibodies. Ninety married men from couples with isolated male infertility related to either a positive sperm immobilization test (SIT) and/or gelatin agglutination test (GIT) were randomized to 60 days of either Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang (n = 60) or control of prednisone 5 mg and clomiphene 50 mg (n = 30). Men with a persistently positive SIT or GIT after 60 days of treatment were extended another 60 days of the same treatment. Men with persistently positive SIT or GIT after 120 days of treatment were extended another 60 days of treatment up to a maximum of 180 days of treatment. Treatment with 2 months of Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang decreased IgA, IgG, and IgM (P < 0.01). Treatment with 4 months of prednisone and clomiphene also decreased IgA, IgG, and IgM (P < 0.01), but the improvement was less when compared to 4 months of Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang (statistical analysis not published). Pregnancy within 1 year of completing treatment was 83% (50 of 60) for the wives of the men treated with Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang, compared to 56.6% (17 of 30) for the wives of men on prednisone and clomiphene.76

The clinical data on Chinese herbal medications for male infertility are intriguing. The nonstandardization of herbal decoctions, however, makes studies difficult to perform. RCTs and standardization of the herbal decoctions are needed to assess the clinical relevance of this treatment.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a key component in TCM fertility therapy. Acupuncture is often an adjunctive therapy, used with or without electrical stimulation, and in combination with herbal medicines for male infertility. Two RCTs assessing the effect of acupuncture on male infertility are reviewed.

A study of 57 men with severe oligoasthenospermia underwent either true or placebo acupuncture. Those who underwent true acupuncture experienced improvement in total motile sperm counts (33.8% vs 24.4% motility A-C, P = 0.035) but lower semen volume (3.7 vs 4.2 ml, P = 0.041).77 In a physiologic study of 80 healthy men 30–35 years of age, Doppler ultrasound flowmetry was used to assess differences in testicular blood flow before and after abdominal electroacupuncture. Men who received acupuncture at points correlating to genital problems (ST-29 or guilai) with electrical stimulation (10 Hz) demonstrated improvements in testicular blood flow (P < 0.005). Electroacupuncture using a lower stimulation (2 Hz or 10 Hz) or at a different location (ST-25 or tianshu) showed no change in testicular blood flow.78

The results of acupuncture on sperm parameters are mixed with one study demonstrating improvement in total motile sperm count, but no improvement in sperm concentration, motility, or morphology, and decline of semen volume. The second study showed a testicular artery response to abdominal electroacupuncture but did not assess if this has clinical relevance for male infertility. An RCT on acupuncture with pregnancy or live birth rate as an outcome is needed before a conclusion can be made about clinical efficacy.

Mind-body practice

Tai chi and qigong are mind-body practices that originated in China that combine meditation with exercise to improve the flow of qi throughout the body. Tai chi originated as a martial art that has evolved to an exercise promoted for general health. Qigong is a form of exercise that is recognized as a standard medical technique in China. The difference between the two lies in the complexity of movements, with qigong being a simpler form utilizing repetitive body movements and breathing techniques. The role of both tai chi and qigong in male infertility is to integrate body, breath, and mind, to achieve mental clarity, body homeostasis, and heightened sexual energy and libido. A literature review of RCTs for tai chi and qigong suggests improvements in bone density, stress management, and immune response, and a reduction in falls,79 but no study assessed specific parameters of male infertility.

Yoga is a physical, mental, and spiritual discipline that originated in India. Yoga focuses on gentle stretching, exercises for breath control, and meditation. The role of yoga in male infertility focuses on reducing anxiety and optimizing erectile function.80

There were no clinical studies that directly evaluated sperm quality, pregnancy rate, or live birth rate, in relationship to tai chi, qigong, or yoga. Further studies are needed to assess if mind-body practices improve male fertility.

Support therapies

Scrotal cooling

The idea of scrotal cooling to benefit male fertility is based on the negative relationship of scrotal heat and spermatogenesis. The scrotal temperature of infertile men is 0.4–0.5°C higher than in fertile men.81 Further, a rise of 1°C in median scrotal temperature results in a 40% drop in sperm concentration.82 These findings contribute to the common belief that “boxers are better than briefs,” though this has never been proven.

There is no RCT study on the effect of scrotal cooling and male infertility. Several small observational studies evaluated the effect of scrotal cooling on male infertility. The first study was published nearly 50 years ago. Seven oligospermic men used scrotal cooling for 14 consecutive days. Sperm count increased, but this effect did not persist beyond 2 weeks.83 A series of observational studies on scrotal cooling was conducted in the 1980s for infertile men with abnormal semen parameters and elevated testis temperatures. Men were treated with scrotal cooling for 8–20 weeks. Sperm parameters improved in 64%–83% of men and pregnancy was achieved in 14%–50% of couples.84,85,86,87 Discontinuance of hypothermia resulted in a return to pretreatment semen parameters.85 The percentage of improved semen parameters was the same whether or not a varicocele was present.87

There are two prospective controlled studies on scrotal cooling. In both studies, scrotal cooling was done for 12 weeks. In one study of 40 infertile men with oligoasthenoteratospermia, scrotal cooling to decrease the scrotal temperature by 1°C improved sperm concentration (P < 0.0001), motility (P < 0.05) and morphology (P < 0.05) after 8 and 12 weeks of treatment, compared to baseline sperm parameters.88 In a separate study of 40 infertile men with oligospermia and testicular maldescent, scrotal cooling to decrease the scrotal temperature by 0.8°C improved sperm concentration (P < 0.01) at 8 and 12 weeks of treatment compared to baseline sperm parameters, but there were no improvements in sperm motility or morphology. Pregnancy rate during the 12-week treatment period was 20% (4 of 20 men), but no information about pregnancy was provided about the matched control group.89 There was no difference in testosterone and FSH in both studies. LH was increased with scrotal cooling in oligoasthenoteratospermic men but not in men with oligospermia and testicular maldescent.

The evidence for the beneficial effect of scrotal cooling on male fertility is based on small observational studies without matched control groups and two prospective controlled trials. Some improvements in sperm count began following 2 weeks of scrotal cooling, but the most robust increase in sperm count occurred at 8 weeks. Achievement of pregnancy following scrotal cooling was not adequately assessed as pregnancy was never a primary outcome in any of the studies.90 Scrotal cooling does not harm and may improve sperm parameters. However, there is no ideal device for scrotal cooling on the market. A randomized controlled trial on scrotal cooling using a hydrogel pad containing I-menthol, FertilMate™, is in the initial recruitment phase.91

Faith based treatment

Faith healing, including spiritual or prayer therapy, for infertility, is practiced by different cultures all over the world.

Several studies assessed the use of faith healing in the Middle East and Africa. On a survey of 1021 patients attending an infertility clinic in Jordan, of which 25% were male, 45% utilized complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Of people reporting to use CAM for infertility, 44% employed religious healing.92 In a Lebanese cross-sectional study of 213 consecutive patients, 41% reported using a CAM modality for their infertility. Of the men using CAM modalities, 32% used faith healing.93 A survey of rural ingenuous healers in South Africa found that 91% of these healers treat infertility on a regular basis.94

Faith healing for fertility is also a part of the Western world. Several Christian websites such as www.whatchristianswanttoknow.com, www.catholicinfertility.org, and www.stronginfaith.org, describe prayer as a remedy for infertility, though the focus is primarily on women. The role of spiritual therapy for male infertility in the Christian community is not a method of achieving pregnancy per se, but rather a focus on hope, strength of will, and preservation of a domestic relationship through love and support. The website www.ldsinfertilty.org invokes the stories of Abraham and Isaac for inspiration. Suggestions for infertile men is to do as Abraham who “exercised remarkable faith, had abiding hope, and remained faithful to the Lord” or to act as Isaac “to plead righteously” and make “a deeply sincere and determined request of the Lord.”

Faith healing is a component of male infertility treatment across cultures. As there is no study on clinical effectiveness in terms of sperm parameters, pregnancy rates, and live birth rates, no recommendation can be made regarding faith healing.

CONCLUSIONS

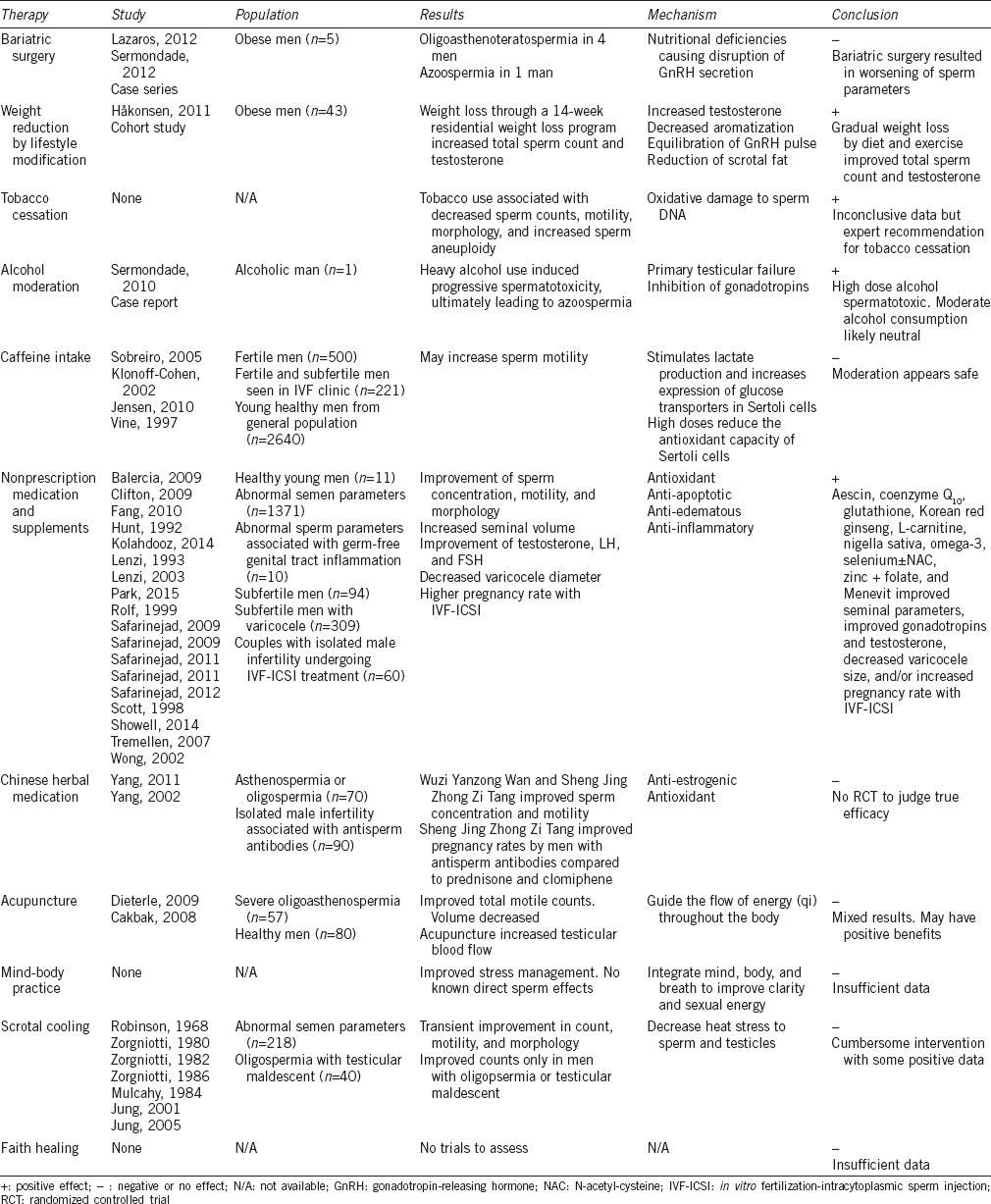

Whether it is as a supplement to or instead of conventional allopathic therapy, men are increasingly using lifestyle modifications and following holistic, complementary, and alternative therapies for the management of male infertility. A summary of outcomes and conclusions from several of these therapeutic modalities is provided in Table 2. Valid strategies include weight reduction by diet and exercise, smoking cessation, and alcohol moderation. Supplements assessed with a RCT to have positive effects on male fertility include aescin, coenzyme Q10, glutathione, Korean red ginseng, L-carnitine, nigella sativa, omega-3, selenium, combination of zinc and folate, and the Menevit antioxidant. There are some studies suggesting benefit from Chinese herbal medications, acupuncture, and scrotal cooling, but the data are currently insufficient to make recommendations. While clinical evidence for mind-body practice and faith based healing is sparse, a familiarity to these complementary approaches allows us to be better practitioners for the many patients who value these therapies.

Table 2.

Outcomes and conclusions from all therapeutic modalities for male infertility

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Ali BM, Gutsxhi T, Pummer K, Zigeuner R, Brookman-May S, et al. Body mass index has no impact on sperm quality but on reproductive hormones levels. Andrologia. 2014;46:106–11. doi: 10.1111/and.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sermondade N, Faure C, Fezeu L, Shayeb AG, Bonde JP, et al. BMI in relation to sperm count: an updated systematic review and collaborative meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:221–31. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg ML, Kim S, Chen Z, Sundaram R, Schisterman EF, et al. The relationship between BMI and waist circumference on semen quality: data from the LIFE study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:193–200. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michalakis K, Mintziori G, Kaprara A, Taelatzis BC, Goulis DG. The complex interaction between obesity, metabolic syndrome and reproductive axis: a narrative review. Metabolism. 2013;62:457–78. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank DM, Clark RV, Heymsfield SB, Rudman DR, Blank MS. Endogenous opiods and hypogonadism in human obesity. Brain Res Bull. 1994;34:571–4. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafik A, Olfat S. Scrotal lipomatosis. Br J Urol. 1981;53:50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1981.tb03128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazaros L, Hatzi E, Markoula S, Takenaka A, Sofikitis N, et al. Dramatic reduction in sperm reduction following bariatric surgery: report in two cases. Andrologia. 2012;44:428–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2012.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sermondade N, Massin N, Boitrelle F, Pfeffer J, Eustache F, et al. Sperm parameters and male fertility after bariatric surgery: three case series. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24:206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Håkonsen LB, Thulstrup AM, Aggerholm AS, Olsen J, Bonde JP, et al. Does weight loss improve semen quality and reproductive hormones. Results from a cohort of severely obese men? Reprod Health. 2011;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes EG, Brennan BG. Does cigarette smoking impair natural or assisted fecundity? Fertil Steril. 1996;66:679–89. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aryanpur M, Tarahomi M, Sharifi H, Heydari G, Hessami Z, et al. Comparison of spermatozoa quality in male smokers and nonsmokers of Iranian infertile couples. Int J Fertil Steril. 2011;5:152–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaur DS, Talekar MS, Pathak VP. Alcohol intake and cigarette smoking: impact of two major lifestyle factors on male fertility. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:35–40. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubes J, Lowe X, Moore D, Perreault S, Slott V. Smoking cigarettes is associated with increased sperm disomy in teenage men. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:715–23. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Said TM, Ranga G, Agarwal A. Relationship between semen quality and tobacco chewing in men undergoing infertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:649–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis KM, Savitz DA, Arbuckle TE. Effects of cigarette smoking, caffeine consuption, and alcohol intake on fecundability. Am J Epidermiol. 1997;146:32–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenzes MT, Bielecki R, Reed TE. Detection of benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts in sperm of men exposed to cigarette smoke. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:330–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasqualotto FF, Umezu FM, Salvador M, Borges E, Sobreiro BP, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on antioxidant levels and presence of leukocytospermia in infertile men: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfeifer S, Fritz M, Goldberg J, McClure RD, Thomas M, et al. Smoking and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen TK, Swan S, Jørgensen N, Toppari J, Redmon B, et al. Alcohol and male reproductive health: a cross-sectional study of 8344 healthy men from Europe and the USA. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1801–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pajarinen J, Karhunen PJ, Savolaninen V, Lalu K, Penttilä A, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and disorders of human spermatogenesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:332–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthusami KR, Chinnaswamy P. Effect of chronic alcoholism on male fertility hormones and semen quality. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:919–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kucheria K, Saxena R, Mohan D. Semen analysis in alcohol dependence syndrome. Andrologia. 1985;17:558–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1985.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klonoff-Cohen H, Lam-Kruglick P, Gonzalez C. Effects of maternal and paternal alcohol consumption on the success rates of in vitro fertilization and gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:330–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sermondade N, Elloumi H, Berthaut I, Mathieu E, Delarouzière V, et al. Progressive alcohol-induced sperm alterations leading to spermatogenic arrest, which was reversed after alcohol withdrawal. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20:324–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobreiro BP, Lucon AM, Pasqualotto FF, Hallak J, Athayde KS, et al. Semen analysis in fertile patients undergoing vasectomy: reference values and variations according to age, length of sexual abstinence, seasonality, smoking habits and caffeine intake. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123:161–6. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802005000400002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen TK, Swan SH, Skakkebaek NE, Rasmussen S, Jørgensen N. Caffeine intake and semen quality in a population of 2,554 young Danish men. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:883–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klonoff-Cohen H, Bleha J, Lam-Kruglick P. A prospective study of the effects of female and male caffeine consumption on the reproductive endpoints of IVF and gamete intra-Fallopian transfer. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1746–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vine MF, Setzer RW, Everson RB, Wyrobek AJ. Human sperm morphometry and smoking, caffeine, and alcohol consumption. Reprod Toxicol. 1997;11:179–84. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(97)00004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenfeld C, Amelar RD, Dubin L. Stimulation of ejaculated human spermatozoa by caffeine. Fertil Steril. 1975;26:158–61. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)40936-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aitken RJ, Best F, Richardson DW, Schats R, Simm G. Influence of caffeine on movement characteristics, fertilizing capacity and ability to penetrate cervical mucus of human spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil. 1983;67:19–27. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0670019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barkay J, Zuckerman H, Sklan D, Gordon S. Effect of caffeine on increasing the motility of frozen human sperm. Fertil Steril. 1977;28:175–7. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)42378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammitt DG, Bedja E, Rogers PR, Syrop CH, Donovan JF, et al. Comparison of motility stimulants for cryopreserved human semen. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60925-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison RF. Insemination of husband's semen with and without the addition of caffeine. Fertil Steril. 1978;29:532–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)43279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imoedemhe DA, Sigue AB, Pacpaco EL, Olazo AB. The effect of caffeine on the ability of spermatozoa to fertilize mature human oocytes. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1992;9:155–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01203756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison RF, Sheppard BL, Kaliszer M. Observations on the motility, ultrastructure and elemental composition of human spermatozoa incubated with caffeine. Andrologica. 1980;12:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1980.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barkay J, Bartoov B, Ben-Ezra S, Langsam J, Feldman E, et al. The influence of in vitro caffeine treatment on human sperm morphology and fertilizing capacity. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:913–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)47907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dias TR, Alves MG, Bernardino RL, Martins AD, Moreira AC, et al. Dose-dependent effects of caffeine in human Sertoli cells metabolism and oxidative profile: relevance for male fertility. Toxicology. 2015;328:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sirtori CR. Aescin: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic profile. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:183–93. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrasco OF, Vidrio H. Endothelium protectant and contractile effects of the antivaricose principle escin in rat aorta. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;47:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD003230. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003230.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang Y, Zhao L, Yan F, Xia X, Xu D, et al. Escin improves sperm quality in male patients with varicocele-associated infertility. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:192–6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraga CG, Motchnik PA, Shigenaga MK. Ascorbic acid protects against endogenous oxidatative DNA damage in human sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:11003–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Therond P, Anger J, Legrand A, Jouannet P. Alpha-tocopherol in human spermatozoa and seminal plasma: relationships with motility, antioxidant enzymes and leukocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:739–44. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.10.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rolf C, Cooper TG, Yeung CH, Nieschlag E. Antioxidant treatment of patients with asthenozoospermia or moderate oligoasthenozoospermia with high-dose Vitamin C and Vitamin E: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1023–33. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.4.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ernster L, Dallner G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1271:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balercia G, Buldreghini E, Vignini A, Tiano L, Paggi F, et al. Coenzyme Q10 treatment in infertile men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1785–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Effects of the reduced form of coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) on semen parameters in men with idiopathic infertility: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J Urol. 2012;188:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.03.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S. Efficacy of selenium and/or N-acetyl-cysteine for improving semen parameters in infertile men: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J Urol. 2009;181:741–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. A prospective double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of the effect of saffron (Crocus sativus Linn.) on semen parameters and seminal plasma antioxidant capacity in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Phytother Res. 2011;25:508–16. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenzi A, Culasso F, Gandini L, Lombardo F, Dondero F. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial of glutathione therapy in male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1657–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi KT. Botanical characteristics, pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean Panax ginseng C A Meyer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:1109–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park HJ, Choe S, Park NC. Effects of Korean red ginseng on semen parameters in male infertility patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study. Chin J Integr Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2139-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bremer J. Carnitine – Metabolism and functions. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:1420–80. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.4.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arduini A. Carnitine and its acyl esters as secondary antioxidants? Am Heart J. 1992;123:1726–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90850-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lenzi A, Lombardo F, Sgro P, Salacone P, Caponecchia L, et al. Use of carnitine therapy in selected cases of male factor infertility: a double-blind crossover trial. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolahdooz M, Nasri S, Modarres SZ, Kianbakht S, Huseini HF. Effects of Nigella sativa L.seed oil on abnormal semen quality in infertile men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:901–5. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conquer JA, Martin JB, Tummon I, Watson L, Tekpetey F. Fatty acid analysis of blood serum, seminal plasma, and spermatozoa of normozoospermic vs.asthenozoospermic males. Lipids. 1999;34:793–9. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Safarinejad MR. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on semen profile and enzymatic anti-oxidant capacity of seminal plasma in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratospermia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised study. Andrologia. 2011;43:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, et al. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179:588–90. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4073.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott R, Macpherson A, Yates RW, Hussain B, Dixon J. The effect of oral selenium supplementation on human sperm motility. Br J Urol. 1998;82:76–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Safarinejad MR. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 on semen parameters, sperm function and reproductive hormones in infertile men. J Urol. 2009;182:237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zago MP, Oteiza PI. The antioxidant properties of zinc: interactions with iron and antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:266–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chimienti F, Aouffen M, Favier A, Seve M. Zinc homeostasis regulating proteins: new drug targets for triggering cell fate. Curr Drug Targets. 2003;4:323–38. doi: 10.2174/1389450033491082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ebisch IM, Thomas CM, Peters WH, Braat DD, Steegers-Theunissen RP. The importance of folate, zinc and antioxidants in the pathogenesis and prevention of subfertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:163–74. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hunt CD, Johnson PE, Herbel J, Mullen LK. Effects of dietary zinc depletion on seminal volume and zinc loss, serum testosterone concentrations, and serum morphology in young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:148–57. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong WY, Merkus HM, Thomas CM, Menkveld R, Zielhuis GA, et al. Effects of folic acid and zinc sulfate on male factor subfertility: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:491–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kefer JC, Agarwal A, Sabanegh E. Role of antioxidants in the treatment of male infertility. Int J Urol. 2009;16:449–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agarwal A, Saleh RA. Role of oxidants in male infertility: rationale, significance, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:817–27. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Desai N, Sabanegh E, Kim T, Agarwal A. Free radical theory of aging: implications in male infertility. Urology. 2010;75:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Showell MG, Mackenzie-Proctor R, Brown J, Yazdani A, Stankiewicz MT, et al. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007411.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clifton GD, Ellington JE. Poster Presented at: American Society of Andrology. Philadelphia, USA, 34th Annual Meeting; 4-7 April; 2009. Prospective Study of FertilAid Vitamin in Men with Low Sperm Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tremellen K, Miari G, Froiland D, Thompson J. A randomized control trial examining the effect of an antioxidant (Menevit) on pregnancy outcome during IVF-ICSI treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:216–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tempest HG, Homa ST, Routledge EJ, Garner A, Zhai X, et al. Plants used in Chinese medicine for the treatment of male infertility possess antioxidant and anti-oestrogenic activity. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2008;54:185–95. doi: 10.1080/19396360802379073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang B, Zhang C, Yang J. Clinical observations on therapeutic effects of the modified Shengjing Zhongzi Tang in patients with asthenospermia and oligozoospermia. J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;31:192–4. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(11)60040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang B, Zhang C, Lei D, Xiaohai S, Peng Z, et al. Clinical study on the treatment of male immune infertility with Sheng Jing Zhong Zi Tang. J Tradit Clin Med. 2002;22:102–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dieterle S, Li C, Greb R, Bartzsch F, Hatzmann W, et al. A prospective randomized placebo-controlled study of the effect of acupuncture in infertile patients with severe oligoasthenozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1340–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cakbak YO, Akpinar IN, Ekinci G, Bekiroglu N. Point- and frequency-specific response of the testicular artery to abdominal electroacupuncture in humans. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1732–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jahnke R, Larkey L, Rogers C, Etnier J, Lin F. A comprehensive review of health benefits of qigong and tai chi. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24:e1–25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081013-LIT-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sengupta P, Chaudhuri P, Bhattacharya K. Male reproductive health and yoga. Int J Yoga. 2013;6:87–95. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.113391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mieusset R, Bujan L, Mondinat C. Association of scrotal hyperthermia with impaired spermatogenesis in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 1987;48:1006–11. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hjollund NH, Storgaard L, Ernst E. Impact of diurnal scrotal temperature on semen quality. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:215–21. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robinson D, Rock J, Menkin MF. Control of human spermatogenesis by induced changes of intrascrotal temperature. JAMA. 1968;204:290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zorgniotti AW, Seaflon AI, Toth A. Chronic scrotal hypothermia as a treatment for poor semen quality. Lancet. 1980;1:904–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zorgniotti AW, Seaflon AI, Toth A. Further clinical experience with testis hypothermia for infertility due to poor semen. Urology. 1982;19:636–40. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(82)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zorgniotti AW, Cohen MS, Seaflon AI. Chronic scrotal hypothermia: results in 90 infertile couples. J Urol. 1986;135:944–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mulcahy JJ. Scrotal hypothermia and the infertile man. J Urol. 1984;132:469–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jung A, Eberl M, Schill WB. Improvements of semen quality by nocturnal scrotal cooling and moderate behavioural change to reduce genital heat stress in men with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Reproduction. 2001;121:595–603. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jung A, Schill WB, Schuppe HC. Improvement of semen quality by nocturnal scrotal cooling in oligozoospermic men with a history of testicular maldescent. Int J Androl. 2005;28:93–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nikolopoulos I, Osman W, Haoula Z, Jayaprakasan K, Atiomo W. Scrotal cooling and its benefits to male fertility: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:338–42. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.758088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Osman MW, Nikolopoulos I, Haoula Z, Kannamannadiar J, Atiomo W. A study of the effect of the FertilMateTM scrotum cooling patch on male fertility. SCOP trial (scrotal cooling patch) – Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bardaweel SK, Shehadeh M, Suaifan GA, Kilani MV. Complementary and alternative medicine utilization by a sample of infertile couples in Jordan for infertility treatment: clinics-based survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ghazeeri GS, Awwad JT, Alameddine M, Younes ZM, Naja F. Prevalence and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use among infertile patients in Lebanon: a cross sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:129. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shai-Mahoko SN. Indigenous healers in the North West Province: a survey of their clinical activities in health care in the rural areas. Curationis. 1996;19:31–4. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v19i4.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]