Abstract

This study was to investigate the effect of annexin A5 on testosterone secretion from primary rat Leydig cells and the underlying mechanisms. Isolated rat Leydig cells were treated with annexin A5. Testosterone production was detected by chemiluminescence assay. The protein and mRNA of Steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR), P450scc, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD), and 17α-hydroxylase were examined by Western blotting and semi-quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. Annexin A5 significantly stimulated testosterone secretion from rat Leydig cells in dose- and time-dependent manners and increased mRNA and protein expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD but not 17α-hydroxylase. Annexin A5 knockdown by siRNA significantly decreased the level of testosterone and protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD. The significant activation of ERK1/2 signaling was observed at 5, 10, and 30 min after annexin A5 treatment. After the pretreatment of Leydig cells with ERK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μmol l−1) for 20 min, the effects of annexin A5 on promoting testosterone secretion and increasing the expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD were completely abrogated (P < 0.05). Thus, ERK1/2 signaling is involved in the roles of annexin A5 in mediating testosterone production and the expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD in Leydig cells.

Keywords: 17β-HSD, 3β-HSD, annexin A5, P450scc, StAR, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Annexin A5 is a member of the annexin family proteins that bind phospholipids in a calcium dependent manner.1 Annexin A5 was first identified as a protein with structural similarity to annexin 1 that is a mediator of the anti-inflammatory activity of glucocorticoids via inhibiting phospholipase A22,3,4,5 and an inhibitor of blood coagulation.6 Annexin A5 also shows the inhibitory activity7,8,9 and forms calcium channels on phospholipid membranes.10,11,12,13 Although the biochemical properties of annexin family proteins suggest important roles in cell functions, the function of these proteins in the physiological process is still obscure.14 Kawaminami et al. found that annexin A5 was expressed in the regressing corpus luteum.15 The expression of annexin A5 in the luteal cells was accompanied by apoptotic change, which was inhibited by the local administration of a GnRH receptor antagonist. Thus, annexin A5 synthesis is stimulated by GnRH in the ovary.15

It has been reported that annexin A5 is expressed in the Leydig cells and Sertoli cells of rat.16,17 We previously reported that both hCG and GnRH agonists increased the expression of annexin A5 and testosterone secretion in the primary rat Leydig cells in vitro. Moreover, hCG increased the expression and the localization of annexin A5 in the whole interstitial tissue of testes.18 These observations suggest that the expression of annexin A5 in Leydig cells leads to its secretion into the interstitial tissue of testes where annexin A5 regulates testosterone synthesis and secretion.

Therefore, this study was to investigate the effects of annexin A5 on steroidogenesis in rat Leydig cells and to reveal the mechanism how annexin A5 modulates testosterone production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The rat annexin A5 was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's nutrient mixture F12 (DMEM/F12) was purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). Percoll, HEPES, collagenase type I were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. (Paisley, Scotland, UK). PD-98059 and Reverse-Transcription System were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Antibodies against StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). β-actin antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse, and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Boster (Wuhan, China).

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (9–10 weeks old) were bred in our laboratory. The animal room was maintained at 22–24°C under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Animals were fed with standard pellet diet and water ad libitum. The animal experiments were performed following the guidelines for animal treatment of Nanjing Jinling Hospital and approved by the Local Ethics Committee, which is in accordance with the principles and procedure of the NIH guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Leydig cell isolation, culture, and treatment

Leydig cells were prepared from rat testes by collagenase treatment as described previously.19 Briefly, decapsulated testes were incubated with collagenase type I (0.25 mg ml−1) for 20 min at 37°C. The crude interstitial cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 ×g for 10 min, then washed twice in HBSS containing 0.1% BSA (w/v). To obtain pure Leydig cells, crude cell suspension was loaded on the top of a discontinuous Percoll gradient (20%, 40%, 60%, and 90% Percoll in HBSS) and subsequently centrifuged at 800 ×g for 20 min. The fractions enriched in Leydig cells were obtained and centrifuged in a continuous, self-generating density gradient starting with 60% Percoll at 20 000 ×g for 30 min at 4°C.

The total number of cells and the percentage of 3β-HSD-positive cells were determined by the protocol for Leydig cell preparation.20 The purity of Leydig cells was 85%–90%. The cell viability, as assessed by Trypan blue exclusion, was >90%. The purified Leydig cells were washed twice with DMEM-F/12 and resuspended in DMEM-F/12 supplemented with 15 mmol l−1 HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mg ml−1 BSA, 365 mg l−1 glutamine, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin.

For Leydig cell culture, 2 ml cell suspension containing 106 cells ml−1 was plated into each well of 6-well plate (Costar, NY, USA) and incubated at 34°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air for 24 h. For testosterone measurement, the cells were incubated with fresh medium containing increasing concentrations of annexin A5 (0, 0.1, 1.0, 10 nmol l−1) for different time (6, 12, 24 h). After incubation, culture medium was collected and frozen at −20°C for testosterone measurement. For total RNA and protein extraction, the cells were washed once with fresh medium and serum-starved for 6 h, then stimulated with 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 for 24 h. For the detection of ERK activation, Leydig cells were serum-starved for 6 h, then treated with 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 for 0, 5, 10, 30, 60, and 90 min. The phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) and total ERK (T-ERK) were detected by Western blotting. To investigate whether the effect of annexin A5 on testosterone secretion in rat Leydig cells is mediated by ERK signaling pathway, PD98059 (50 μmol l−1), a specific inhibitor of ERK, was added 20 min before annexin A5 treatment. Testosterone level was determined by chemiluminescence assay and protein expression (StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD) was examined after 24 h treatment by Western blotting.

Transfection of siRNAs in Leydig cells

Four siRNA duplexes were synthesized commercially by Bioneer with the help of tools available online (http://www.bioneer.com). siRNA1: 5’-GAG CAU ACC UGC CUA CCU U (dTdT)-3’, siRNA2: 5’-GUU UUC UAU CCU CUU CUA A (dTdT)-3’, and siRNA3: 5’-GAC AGA CCU UCC CAC GUC U (dTdT)-3’ were designed to target different coding regions of the Rattus norvegicus annexin A5 mRNA (Gene Bank Accession No. NM_013132.1). The sequences of negative control were: 5’-CCU ACG CCA CCA CUU AUU UCG U (dTdT)-3’.

The day before transfection, 2 × 106 cells in 2 ml of DMEM without antibiotics were plated so that cells will be 70%–90% confluent at the time of transfection. The annexin A5 siRNA was transfected into cells by GenEscortTM II, an efficient transfection reagent, according to the product manual. Briefly, 1ug annexin A5 siRNA and 2ul GenEscortTM II were diluted and mixed in 50 μl PBS in different tube respectively, then the GenEscortTM II dilution was added to the siRNA dilution and mixed gently, and then incubated for 10–15 min at room temperature to allow transfection complex formation. The transfection complex was then added to the cells. After culture for 48 h at 34°C with 5% CO2, the cells in the 6-well plates were lysed to collect total proteins for Western blotting.

RNA extraction and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA in Leydig cells was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instruction. The quality and concentration of RNA were determined with Eppendorf Biophotometer (Germany). Total RNA was reversely transcribed with Reverse-Transcription System in a total volume of 25 μl including 5 × AMV Buffer, 2.5 mmol l−1 dNTP, OligdT, 10 U μl−1 AMV together with 1ug RNA as the template. The reaction was run at 42°C for 60 min, and 95°C for 5 min to terminate the reaction.

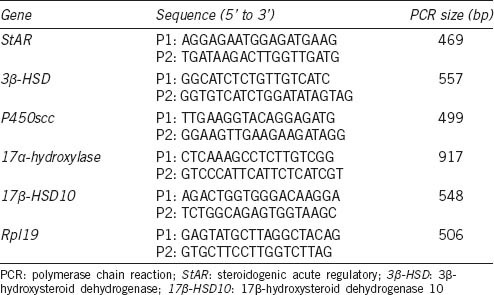

After reverse-transcription, the PCR was carried out for 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s in a final volume of 25 μl containing 2 × PCR Mi × 12.5 μl, 20 μmol l−1 specific forward and reverse primers 1.0 μl, ddH2 O 9.5 μl, and 1 μl cDNA as a template. Primers for 3β-HSD, StAR, P450scc, 17α-hydroxylase, 17β-HSD, and Rpl19 were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software (Table 1). Products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, and densitometric analysis of DNA bands was tested by Quantity One software. The relative expression of 3β-HSD, StAR, P450scc, 17α-hydroxylase, and 17β-HSD mRNAs in different samples was determined by the normalization to the amount of Rpl19 mRNA. Each RT-PCR experiment was repeated at least 3 times, and data were presented as the relative rate of mRNA expression.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers for semi-quantitative PCR

Western blotting analysis

The cells treated with annexin A5 were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 200 μl of ice-cold RIPA buffer (150 mmol l−1 NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mmol l−1 Tris [pH 7.4], 1 mmol l−1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mmol l−1 Na3VO4, and 1 mmol l−1 NaF). The cell lysate was harvested by centrifugation at 10 000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. The protein concentration of supernatants was determined by Bradford method. Thirty microgram of total protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gels, then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF) (Millipore Corporation). The membrane was then blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk powder in TBST (0.5% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline) for 1.5 h at 37°C, and washed 3 times with TBST for 30 min. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for StAR, 450scc, 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD, p-ERK, T-ERK, and β-actin for 16–18 h at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the bands were visualized with ECL (Promega) as described by the manufacturer. The intensity of bands was quantitated by Quantity-One software.

Testosterone determination

The testosterone level in cell culture medium was measured using the Access Testosterone Kit (Backman Coulter, Inc., CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistics

All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. of at least three independent experiments. Differences between the means were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and the LSD method. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Dose- and time-dependent effects of annexin A5 on testosterone production in rat Leydig cells

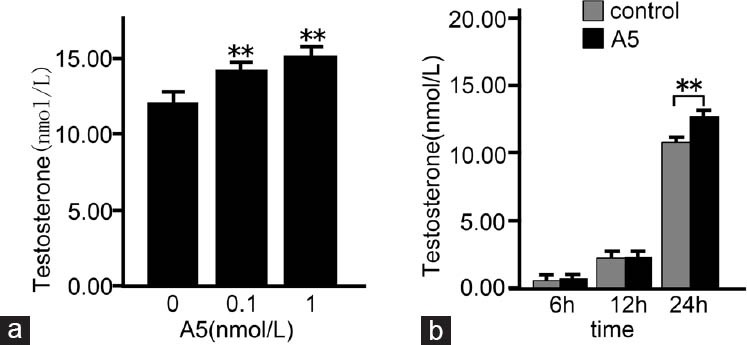

To determine whether annexin A5 can stimulate testosterone production, rat Leydig cells were treated with different concentrations of annexin A5 for 24 h and testosterone production was detected by chemiluminescence assay. As shown in Figure 1a, the level of testosterone was significantly increased by 18% and 26% after treatment with 0.1 nmol l−1 and 1 nmol l−1 of annexin A5 for 24 h (P < 0.01), respectively. Then, annexin A5 at 1 nmol l−1 was used to determine the temporal effect. Time-dependent study indicated that the maximal effect of annexin A5 on testosterone production was seen at 24 h after treatment (P < 0.01; Figure 1b). Therefore, the dose of 1 nmol l−1 and time point of 24 h were used in the following experiments.

Figure 1.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of annexin A5 (A5) on testosterone production in rat Leydig cells. The cells were treated with various concentrations of annexin A5 for 24 h (a) or cells were treated with 1 nmol l−1 of annexin A5 for different time points (b), then culture medium was collected and assayed for testosterone production by chemiluminescence assay. The data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01, compared with the control.

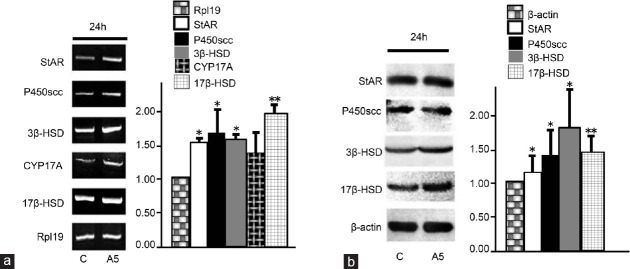

Effects of annexin A5 on the expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, CYP17A, and 17β-HSD in rat Leydig cells

To evaluate the effect of annexin A5 on the expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, CYP17A, and 17β-HSD, rat Leydig cells were treated with 1 nmol l−1 Annexin A5 for 24 h. The mRNA levels of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, CYP17A, and 17β-HSD were examined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 2a, compared with control, the mRNA level of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was increased by 55%, 69%, 59%, and 104%, respectively (P < 0.05), while the CYP17A mRNA expression was not significantly affected (P > 0.05). Moreover, their protein expression was examined by Western blotting. The StAR protein expression was not affected after annexin A5 treatment for 24 h, while the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was significantly increased by 35%, 88%, and 47%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Effects of annexin A5 (A5) on the mRNA and protein expression of StAR and testosterone synthesis-related enzymes in rat Leydig cells. (a) Cells were treated with 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 for 24 h, and the mRNA expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, CYP17A, and 17β-HSD10 was examined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Rpl19 was used as an internal control. (b) The protein expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was detected by Western blotting. Quantitation of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD expression was determined by the normalization to the internal control β-actin. All data represent mean ± s.d. from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with the control.

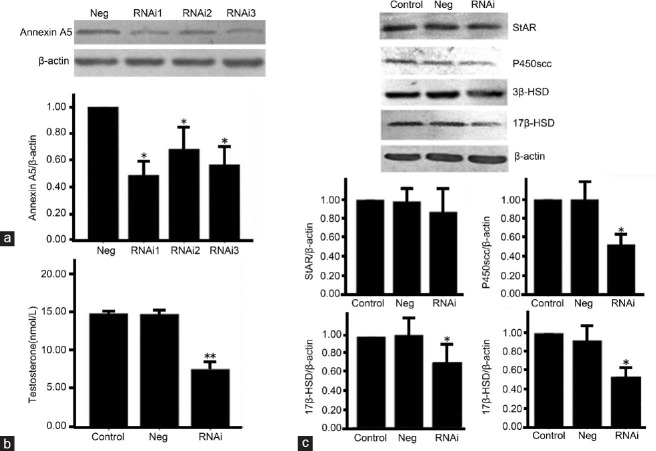

Annexin A5 mediates testosterone production in rat Leydig cells

To verify the effect of annexin A5 on testosterone production and protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD, we transfected three different annexin A5 siRNA duplexes and a negative control into leydig cells. The knockdown effect of annexin A5 was examined at 48 h after transfection by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 3a, compared with the control, all three annexin A5 siRNA duplexes showed the inhibitory effect on annexin A5 expression. The protein expression of annexin A5 was decreased by 51%, 35%, and 43%, respectively (P < 0.05). We further examined the level of testosterone in the supernatant after annexin A5 gene knockdown. As shown in Figure 3b, the level of testosterone was decreased by 49% at 48 h after annexin A5 knockdown (the best siRNA) (P < 0.01). Western blotting results showed that, 48 h after transfection, StAR protein level was not affected by annexin A5 siRNA, while the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was decreased by 48%, 33%, and 53%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 3c). Our results suggest that annexin A5 in leydig cells is involved in mediating testosterone production and the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of annexin A5 inhibits testosterone production and the expression of testosterone synthesis-related enzymes in rat Leydig cells. (a) Leydig cells were transfected with three different siRNAs targeting annexin A5, and the protein expression of annexin A5 was detected at 48 h after transfection by Western blotting. (b) Leydig cells were transfected with annexin A5 siRNA for 48 h, then culture medium was collected and assayed for testosterone production by chemiluminescence assay. (c) Protein expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD in Leydig cells was detected after annexin A5 knockdown. The densitometric analysis of Western blots was determined by the normalization to internal control β-actin. Values are shown as mean ± s.d. from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with negative control.

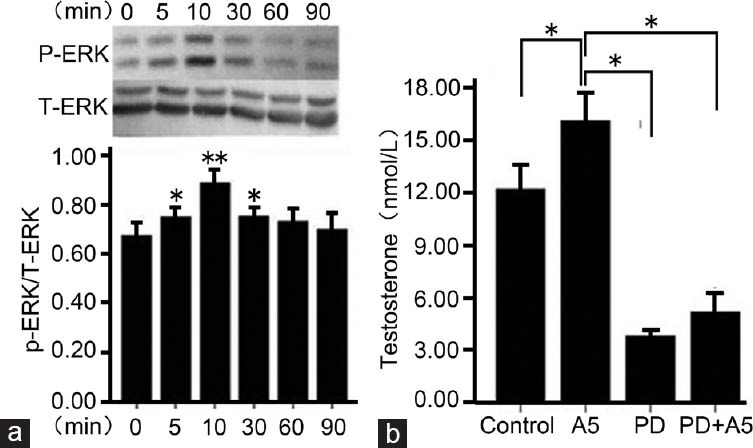

ERK1/2 activation by annexin A5 in rat Leydig cells

To confirm whether the effect of annexin A5 on testosterone secretion in rat Leydig cells is relevant to ERK1/2 signaling pathway, Leydig cells were treated with annexin A5. Annexin A5 induced a significant activation of ERK1/2 at 5, 10, and 30 min, and the maximal increase as high as 33% (vs control) was observed at 10 min (Figure 4a). Total-ERK was not affected by annexin A5 treatment at all-time points. Moreover, Leydig cells were treated with pH 8.0 Tris-HCl, 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5, PD98059 (50 μmol l−1, a specific inhibitor of ERK), and 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 plus PD98059 (PD98059 was added 20 min before Annexin A5 treatment), respectively. The result showed that PD98059 significantly inhibited the secretion of testosterone from Leydig cells, and the promoting effect of annexin A5 on testosterone production was significantly abrogated by PD98059 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

ERK1/2 signaling is involved in annexin A5-stimulated testosterone secretion in Leydig cells. (a) After incubation with annexin A5 (1 nmol l−1) for different time points, activated ERK (P-ERK) and total ERK (T-ERK) were detected by Western blotting. The ratio of P-ERK to T-ERK was calculated. The P-ERK level in Leydig cells without annexin A5 treatment (0 min) was set as a control. (b) Leydig cells were pretreated with 50 μmol l−1 PD98059 (ERK inhibitor) for 20 min, followed by treatment with 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 for 24 h. The control culture was treated with Tris-HCl. Culture medium was collected for testosterone assay by chemiluminescence assay. Values are represented as mean ± s.d. from six individual experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with the control.

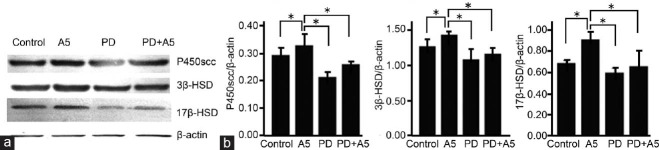

The regulation of P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD expression by annexin A5 is involved in ERK signaling pathway

To investigate whether the regulation of annexin A5 in the expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD is related to ERK1/2 signaling pathway, the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was detected after different treatments (pH 8.0 Tris-HCl, 1 nmol l−1 Annexin A5, 50 μmol l−1 PD98059, 1 nmol l−1 Annexin A5 plus 50 μmol l−1 PD98059). Results showed PD98059 obviously decreased the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD. Moreover, the promoting effect of annexin A5 on protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was also obviously inhibited by PD98059 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

PD98059 pretreatment inhibited the promoting effect of annexin A5 on protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD. Leydig cells were pretreated with 50 μmol l−1 PD98059 for 20 min, followed by treatment with 1 nmol l−1 annexin A5 for 24 h. Control cells were treated with Tris-HCl. The protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD was examined by Western blotting. (a) Representative blotting of P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD proteins. β-actin was used as an internal control; (b) Quantitation of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD expression after normalization to β-actin. Values are represented as mean ± s.d. from six individual experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control

DISCUSSION

To explore the function of annexin A5 on the Leydig cells in the testis, we tested the regulation of annexin A5 on testosterone production in Leydig cells and underlying mechanisms. For the first time, we showed that annexin A5 increased testosterone production in dose- and time-dependent manners in rat Leydig cells. We also found that rat annexin A5 treatment could increase the mRNA expression of StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD in Leydig cells at 24 h. Moreover, the protein expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD in Leydig cells was regulated after annexin A5 treatment. Furthermore, we verified that annexin A5 mediated testosterone production the expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD in rat Leydig cells via the activation of ERK signaling. These results suggest a novel function of annexin A5 in steroidogenesis.

It is well-established that steroidogenesis in Leydig cells is regulated by LH-activated G-protein-adenylate cyclase-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway that phosphorylates or activates proteins. The expression and activity of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD enzymes can be regulated by various factors to regulate steroidogenesis. In the present study, annexin A5 was found to increase testosterone production by upregulating the expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD. However, the promoting effect of annexin A5 on testosterone production is much lower than that of LH, which could increase testosterone production in Leydig cells by as high as 10-fold. Besides its role in testosterone production, we speculate that annexin A5 may regulate other functions in Leydig cells because Annexin A5 can regulate cell migration and apoptosis in the epithelial cells.21,22 Moreover, knockdown of annexin A5 by siRNA could decrease testosterone production in Leydig cells by 50% and the expression of P450scc, 3ί-HSD and 17ί-HSD that are closely related to steroidogenesis. The mRNA expression of StAR in rat Leydig cells was also upregulated significantly by annexin A5 treatment, although its protein expression was not changed. Annexin A5 may regulate StAR expression at transcription level, but the precise mechanism needs further investigation. It is accepted that StAR's entry into mitochondria causes physical contact between the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes, then results in cholesterol decrease to a chemical concentration gradient from the outer to inner membrane. The upregulation of testosterone secretion by annexin A5 is probably not due to the increasing import of cholesterol into mitochondria. These data indicate annexin A5 regulates Leydig cell function through mediating steroid hormone synthesis and the expression of some steroidogenesis-associated proteins.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (MAPK ERK 1/2) has been reported to be involved in the steroidogenesis in Leydig cell.23,24,25,26,27 Gyles et al. reported that MAPK kinase inhibitors inhibited forskolin-stimulated steroid production in the mouse testicular MA-10 cell line,27 which is consistent with our result that ERK inhibitor PD98059 blocked testosterone production induced by annexin A5 in Leydig cells. In human LH receptor-expressing MA-10 cells, hCG was able to increase the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ras and ERK1/2.28 Also, the effect of hCG on the expression of phosphorylated-ERK1/2 was diminished by the inhibition of PKC and PKA responsiveness in immature rat Leydig cells.29 Our previous study demonstrated that the synthesis of annexin A5 is stimulated by GnRH and hCG, and GnRH positively regulates steroidogenesis by activating ERK in rat Leydig cells.18,30 ERK1/2 but not JNKs or p38-MAPKs was activated by GnRH in our previous study,30 and ERK1/2 is also activated by annexin A5 in the current study. Interestingly, JNKs or p38-MAPKs were not activated by annexin A5 in our study. So annexin A5 may be the mediator between the GnRH/hCG and P-ERK1/2.

A previous study demonstrated that annexin A5 was expressed in the Leydig cells of the interstitium and endothelial cells of microvessels. We speculate annexin A5 may exert different functions in Leydig cells and endothelial cells. Annexin A5 promotes testosterone production in Leydig cell by activating ERK1/2, but its role in endothelial cells needs further investigation. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that annexin A5 plays similar roles in both Leydig cells and endothelial cells because annexin A5 may act as an anti-apoptotic agent or a phospholipid stabilizing agent to mediate cell functions via ERK1/2 signaling.

Taken together, we conclude that rat annexin A5 can regulate testosterone secretion in dose- and time-dependent manners. ERK1/2 is involved in annexin A5-induced testosterone secretion in Leydig cells, which is consistent with increased expression of P450scc, 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD in Leydig cells.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Ze He, Qin Sun, Li Chen and Bing Yao carried out the experimental design, participated in Western blotting analysis, testing testosterone, performing statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; Yuan-Jiao Liang and Yi-Feng Ge were responsible for cell culture and RT-PCR; Shi-Feng Yun carried out annexin A5 siRNA knockdown. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed with the order of all authors.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None of the authors declared competing financial interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by State Key Development Program of (for) Basic Research of China (2013CB945200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81070480 and No. 31371520) and Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Projects SBK2010202). The authors declared no conflict of interest that would prejudice the impartiality of this scientific work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crompton MR, Moss SE, Crumpton MJ. Diversity in the lipocortin/calpactin family. Cell. 1988;55:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallner BP, Mattaliano RJ, Hession C, Cate RL, Tizard R, et al. Cloning and expression of human lipocortin, a phospholipase A2 inhibitor with potential anti-inflammatory activity. Nature. 1986;320:77–81. doi: 10.1038/320077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepinsky RB, Tizard R, Mattaliano RJ, Sinclair LK, Miller GT, et al. Five distinct calcium and phospholipid binding proteins share homology with lipocortin I. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10799–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Utsumi T. [Inhibitory effects of calphobindins on phospholipase A2 and phospholipase C] Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;44:793–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mira JP, Dubois T, Oudinet JP, Lukowski S, Russo-Marie F, et al. Inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by annexin V in differentiated permeabilized HL-60 cells. Evidence of crucial importance of domain I type II Ca2+-binding site in the mechanism of inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10474–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Suda M, Nakao H, Nagoya T, Saino Y, et al. Structure and expression of cDNA for an inhibitor of blood coagulation isolated from human placenta: a new lipocortin-like protein. J Biochem. 1987;102:1261–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibata S, Sato H, Maki M. Calphobindin I (annexin V) inhibits protein kinase C. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992;166:479–81. doi: 10.1620/tjem.166.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlaepfer DD, Jones J, Haigler HT. Inhibition of protein kinase C by annexin V. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1886–91. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois T, Mira JP, Feliers D, Solito E, Russo-Marie F, et al. Annexin V inhibits protein kinase C activity via a mechanism of phospholipid sequestration. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 3):1277–82. doi: 10.1042/bj3301277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber R, Schneider M, Mayr I, Romisch J, Paques EP. The calcium binding sites in human annexin V by crystal structure analysis at 2.0 A resolution. Implications for membrane binding and calcium channel activity. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81428-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojas E, Pollard HB, Haigler HT, Parra C, Burns AL. Calcium-activated endonexin II forms calcium channels across acidic phospholipid bilayer membranes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21207–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berendes R, Burger A, Voges D, Demange P, Huber R. Calcium influx through annexin V ion channels into large unilamellar vesicles measured with fura-2. FEBS Lett. 1993;317:131–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81507-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirsch T, Harrison G, Golub EE, Nah HD. The roles of annexins and types II and X collagen in matrix vesicle-mediated mineralization of growth plate cartilage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35577–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerke V, Moss SE. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:331–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawaminami M, Tsuchiyama Y, Saito S, Katayama M, Kurusu S, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulates annexin 5 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the anterior pituitary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:915–20. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giambanco I, Pula G, Ceccarelli P, Bianchi R, Donato R. Immunohistochemical localization of annexin V (CaBP33) in rat organs. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:1189–98. doi: 10.1177/39.9.1833446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaminami M, Kawamoto T, Tanabe T, Yamaguchi K, Mutoh K, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of annexin 5, a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein, in rat endocrine organs. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:85–9. doi: 10.1007/s004410051037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao B, Kawaminami M. Stimulation of annexin A5 expression by gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in the Leydig cells of rats. J Reprod Dev. 2008;54:259–64. doi: 10.1262/jrd.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svechnikov K, Sultana T, Soder O. Age-dependent stimulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by interleukin-1 isoforms. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;182:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payne AH, Downing JR, Wong KL. Luteinizing hormone receptors and testosterone synthesis in two distinct populations of Leydig cells. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1424–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-5-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe M, Kondo S, Mizuno K, Yano W, Nakao H, et al. Promotion of corneal epithelial wound healing in vitro and in vivo by annexin A5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1862–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing MM, de Vries MR, Nordzell M, Pettersson K, de Boer HC, et al. Annexin A5 therapy attenuates vascular inflammation and remodeling and improves endothelial function in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:95–101. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poderoso C, Converso DP, Maloberti P, Duarte A, Neuman I, et al. A mitochondrial kinase complex is essential to mediate an ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of a key regulatory protein in steroid biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Ma P, Huang C, Liu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Expression of chemerin and its receptors in rat testes and its action on testosterone secretion. J Endocrinol. 2014;220:155–63. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin YM, Tsai CC, Chung CL, Chen PR, Sun HS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 9 stimulates steroidogenesis in postnatal Leydig cells. Int J Androl. 2010;33:545–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poderoso C, Maloberti P, Duarte A, Neuman I, Paz C, et al. Hormonal activation of a kinase cascade localized at the mitochondria is required for StAR protein activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;300:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyles SL, Burns CJ, Whitehouse BJ, Sugden D, Marsh PJ, et al. ERKs regulate cyclic AMP-induced steroid synthesis through transcription of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34888–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor-induced phosphorylation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases in leydig cells is mediated by a protein kinase a-dependent activation of ras. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2189–200. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinelle N, Holst M, Soder O, Svechnikov K. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4629–34. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao B, Liu HY, Gu YC, Shi SS, Tao XQ, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone positively regulates steroidogenesis via extracellular signal-regulated kinase in rat Leydig cells. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:438–45. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]