Abstract

Oncogenic osteomalacia (or tumour-induced osteomalacia) is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by overproduction of fibroblastic growth factor 23 (FGF-23) by tumours. Excessive production of FGF-23 can lead to severe, symptomatic hypophosphataemia. The majority of cases have been associated with benign tumours of bone or soft tissue, such as haemangiopericytomas or other neoplasms of mesenchymal origin. We present a case of a 68-year-old woman with an FGF-23 producing B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Treatment with immunochemotherapy resulted in normalisation of serum FGF-23 and phosphate levels.

Background

Hypophosphataemia is a common problem in clinical patients. By determining the renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate it is possible to differentiate between renal and non-renal causes of hypophosphataemia. We describe a case of severe symptomatic hypophosphataemia due to renal phosphate wasting caused by an fibroblastic growth factor 23 (FGF-23) producing B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (B-NHL). To the best of our knowledge, the already rare syndrome of oncogenic osteomalacia has never been described in association with.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old woman presented with progressive left hip pain (without preceding trauma), fever, unintentional weight loss of 20 kg over the past 5 years and a painful intraoral lesion. Her medical history included gastroduodenal ulcers, tuberculosis in a supraclavicular lymph node (treated in 1972), hypertension, hypothyroidism, osteoporosis, cholecystectomy and a hysterectomy. On physical examination, we saw a cachectic woman with a body temperature of 38.5°C. Inspection of the oral cavity showed a small gingival lesion at the left lower jaw. Physical examination was otherwise normal.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations showed severe hypophosphataemia of 0.22 (reference range 0.80–1.40) mmol/L with excessive urinary phosphate loss: tubular phosphate reabsorption 56% (ref >95%) %. Serum levels of calcium, albumin, parathyroid hormone, creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were 1.84 (reference range 2.20–2.65) mmol/L, 35 (reference range 35–50) g/L, 10.6 (reference range 1.0–7.0) pmol/L, 44 (reference range 55–95) µmol/L and 36 (reference range 50–200) nmol/L, respectively. Additional testing revealed an FGF-23 serum concentration of 154 (ref <125) RU/mL.

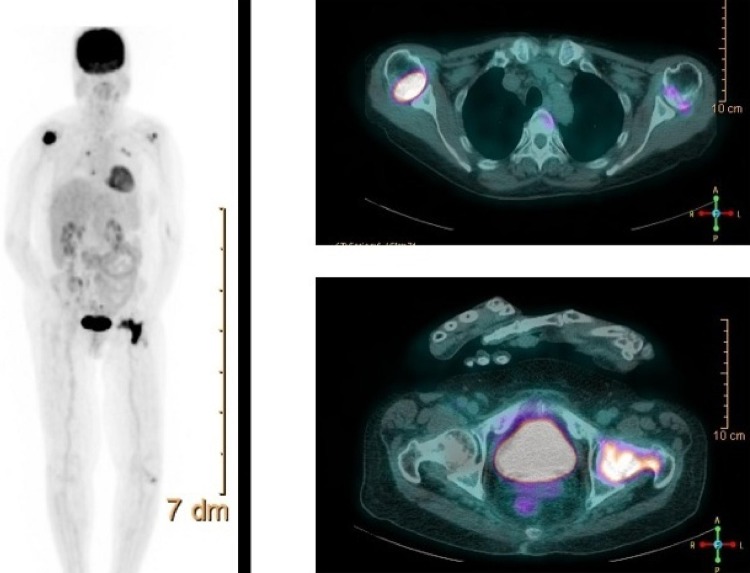

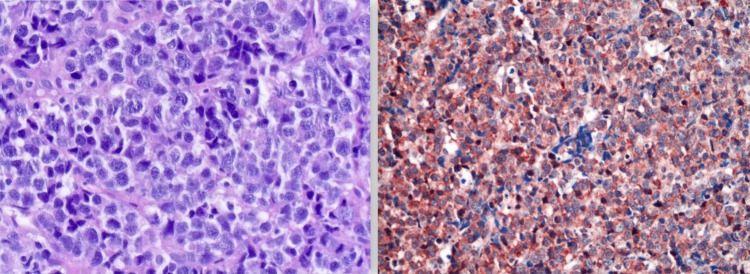

Imaging studies (fludeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and octreotide scintigraphy, figure 1) showed markedly increased uptake in the right proximal humerus and neck of the left femur without pathological masses on CT scan. Biopsy of the intraoral lesion showed diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (DLBCL) (figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining showed extensive expression of FGF-23 in the cytoplasm of malignant B cells (figure 2). A bone marrow biopsy was performed showing no localisation of the DLBCL.

Figure 1.

Fludeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (right) and octreotide scintigraphy (left) showing markedly increased uptake in the right proximal humerus and neck of the left femur without pathological masses on CT scan.

Figure 2.

Biopsy of the intraoral lesion showing diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (left). Additional immunohistochemical staining showing extensive expression of fibroblastic growth factor-23 in the cytoplasm of malignant B cells (right).

Treatment

The patient was treated with 3-weekly rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisolone (R-CHOP21) immunochemotherapy. She was scheduled to receive six cycles of R-CHOP.

Outcome and follow-up

Treatment with R-CHOP resulted in objective tumour response and normalisation of FGF-23 and phosphate levels. Two weeks after administration of the first R-CHOP, the phosphate levels had returned to normal and oral administration of phosphate could be withdrawn. The FGF-23 concentration was measured after the second R-CHOP treatment and had returned to normal.

Unfortunately, the patient died several weeks after the fifth cycle of R-CHOP due to progressive cachexia and infectious complications.

Discussion

Clinical features of oncogenic osteomalacia include bone pain, fractures, gait disturbance and muscle weakness.1 2 It is a rare paraneoplastic phenomenon caused by inappropriate production of the phosphaturic factor FGF-23. Adequate antitumour therapy is the treatment of choice.1 If this is not possible (eg, in case of an undetectable tumour), treatment with active vitamin D and phosphate supplementation is usually successful. Most cases of oncogenic osteomalacia described in the literature have usually been associated with benign tumours of bone or soft tissue,3 4 however, case reports have been described linking colon carcinoma5 and prostate carcinoma6 7 to this phenomenon. To the best of our knowledge, cases have never been described in association with B-NHL.

Learning points.

Hypophosphataemia can have renal and non-renal causes, which can be differentiated by calculation of the tubular phosphate reabsorption ratio.

In case of hypophosphataemia due to renal phosphate, loss the plasma concentration of fibroblastic growth factor-23 should by determined; if elevated, a diagnosis of oncogenic (tumour-induced) osteomalacia should by suspected.

Oncogenic osteomalacia can be cured by treatment of the tumour that causes the syndrome.

If cure of the underlying tumour is not possible or a tumour cannot be found, treatment with phosphate and active vitamin D can ameliorate the symptoms of oncogenic osteomalacia.

Footnotes

Contributors: JHE contributed in arranging the immunohistochemical staining and writing the manuscript. MW contributed in arranging the immunohistochemical staining and reviewing the manuscript. FdJ contributed in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chong WH, Molinolo AA, Chen CC et al. . Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011;18:R53–77. 10.1530/ERC-11-0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T et al. . Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1656–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa020881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu FK, Yuan F, Jiang CY et al. . Tumor-induced osteomalacia with elevated fibroblast growth factor 23: a case of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor mixed with connective tissue variants and review of the literature. Chin J Cancer 2011;30:794–804. 10.5732/cjc.011.10013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y, Xia WB, Xing XP et al. . Tumor-induced osteomalacia: an important cause of adult-onset hypophosphatemic osteomalacia in China: report of 39 cases and review of the literature. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:1967–75. 10.1002/jbmr.1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leaf DE, Pereira RC, Bazari H et al. . Oncogenic osteomalacia due to FGF-23-expressing colon adenocarcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:887–91. 10.1210/jc.2012-3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakahama H, Nakanishi T, Uno H et al. . Prostate cancer-induced oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. Urol Int 1995;55:38–40. 10.1159/000282746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reese DM, Rosen PJ. Oncogenic osteomalacia associated with prostate cancer. J Urol 1997;158(pt 1):887 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64351-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]