Abstract

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) are the most common malignancy in males aged 20 to 39, and the incidence is increasing. TGCTs have a tendency to grow rapidly with a high risk of metastatic spread. TGCTs generally present with a palpable testicular mass, yet may present less commonly with symptoms arising from metastatic disease.

A 24-year-old otherwise healthy male presented with progressive headaches. Initial imaging reported a single mass in the right frontal lobe. Complete surgical resection revealed suspicion for metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma with an inconclusive immunohistochemical profile. Further staging scans revealed pulmonary and pelvic tumor deposits. Tumor markers with alpha-fetoprotein, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase were not elevated. Follow-up cranial magnetic resonance imaging revealed intracranial disease progression and he underwent whole brain radiation therapy. Additional outside pathology consultation for chromosomal analysis revealed features consistent with a TGCT. A scrotal ultrasound revealed a minimally atrophic right testicle. With evidence supporting the potential for response to chemotherapeutic treatment in TGCT, the patient was started on cisplatin and etoposide. Bleomycin was planned for the second cycle of chemotherapy if his pulmonary function improved.

A salient feature of all invasive TGCTs is a gain in material in the short arm of chromosome 12, and is diagnostic if present. Although the initial pathology revealed a non-diagnostic metastatic tumor, further testing revealed amplification of chromosome 12p. The examination of poorly differentiated carcinomas of an unknown primary site using light microscopy and immunohistochemical profiling alone may be inadequate, and should undergo molecular chromosomal analysis.

This case is presented for its unconventional presentation and rarity of occurrence. It brings forward the discussion of both the commonality of TGCT in young male adults, as well as the anomaly of a 'burned out' phenomenon. With unreliable tumor markers, nonspecific symptoms, and pathological findings, ‘burned out’ TGCTs may account for a challenging diagnosis in a variety of cases, especially with the presenting symptom arising from a less common metastatic site. This case adds to the increasing literature on a rare entity of the 'burned out' TGCT, and upon literature review, presents itself as the first reported case presenting with brain metastasis.

Keywords: brain metastasis, regressed, 'burned out' phenomenon, testicular tumour, germ cell tumour, chromosome 12p, case report

Introduction

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) are the most common malignancy diagnosed in males aged 20 to 39, and the incidence is increasing [1-3]. TGCTs have a tendency to grow rapidly with a high risk of metastatic spread. TGCTs generally present with a palpable testicular mass, yet, less commonly may present with symptoms arising from metastatic disease. Specifically, TGCTs have a propensity to metastasize to retroperitoneal lymph nodes, lungs, liver, bones, and less frequently, to the brain [4].

The phenomenon of a primary TGCT outgrowing its blood supply and undergoing auto-infarction has been described as a ‘burned out’ TGCT. The regressed testicular lesion is not appreciable on physical exam, and spontaneous regression occurs without treatment [5]. Despite the regression of the primary testicular tumor, approximately 50% of ‘burned out’ primary testicular tumors continue to harbor malignant cells and distant metastatic disease can progress [6-7]. A ‘burned out’ TGCT can arise, regress, and metastasize within the same testicle. Cases within the literature describe pathological evidence of tumor regression of a testicular mass with a focus of GCT within a clinically unremarkable testicle [4,8]. This can lead to difficulty in making a diagnosis as the metastasis can be mistaken for a primary tumor.

Imaging can be helpful in making the diagnosis, with scrotal ultrasonography revealing evidence of a regressed tumor. Possible findings consist of a hypoechoic area, atrophic testicle, or microcalcifications [7-8]. Macroscopic evidence of a fibrotic scar in the parenchyma and microscopic findings of intratubular germ cells or seminomatous foci may be seen on pathological evaluation [9-11].

Of significance, extra-gonadal germ cell tumors (EGCT) are a known entity that also present with biochemistry and histological findings of a germ cell tumor in the absence of primary testicular or ovarian tumor. However, EGCT are differentiated from ‘burned out’ TGCT by their characteristic midline location, from the pineal gland to the coccyx. Furthermore, in EGCT no radiologic nor pathologic evidence of a primary malignancy is present in the primary reproductive organs [12].

Chemotherapeutic strategies implemented in the 1970s for the treatment of advanced stage TGCTs represents a paradigm shift to a curable disease [13-15]. Here we discuss a rare case that highlights the challenges of diagnosing a ‘burned out’ TGCT.

Case presentation

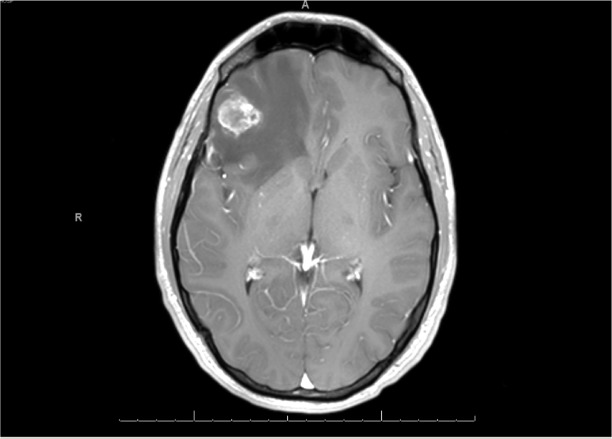

A 24-year-old previously healthy male presented with progressive nausea, vomiting, visual changes, and memory impairment. His only significant finding on history was a strong family history of factor V Leiden mutation. The physical exam was grossly unremarkable. The initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reported a single mass in the right frontal lobe (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Initial Brain MRI.

Single intra-axial heterogeneously enhancing mass in the inferior aspect of the right frontal lobe.

With high suspicion for primary brain tumor, total resection of the intracranial lesion was performed and revealed a metastatic, poorly differentiated carcinoma with an inconclusive immunohistochemical profile.

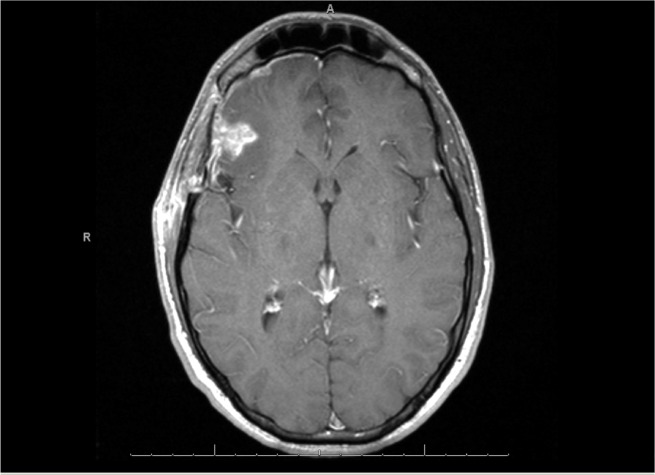

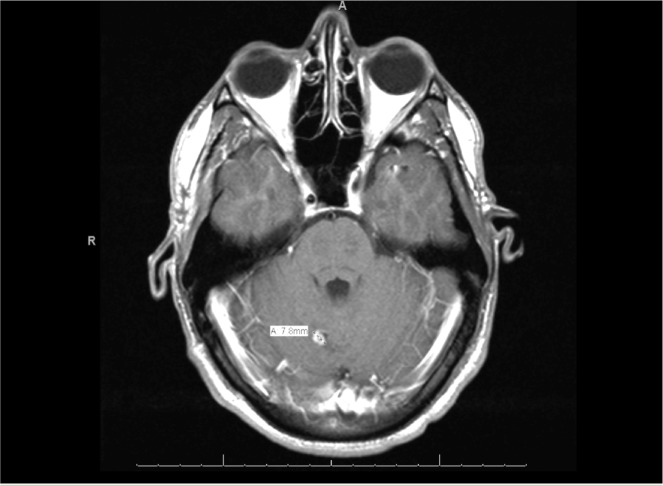

Staging investigations with computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomographic (PET) scans revealed pulmonary and pelvic tumor deposits. A scrotal ultrasound revealed a minimally atrophic right testicle with no further abnormalities detected. A follow-up cranial MRI revealed enhancement in the surgical bed and new metastatic foci (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2. MRI One Month Post-Resection.

Increased enhancement in the surgical bed.

Figure 3. MRI One Month Post-Resection.

New definite enhancing foci compatible with metastatic foci.

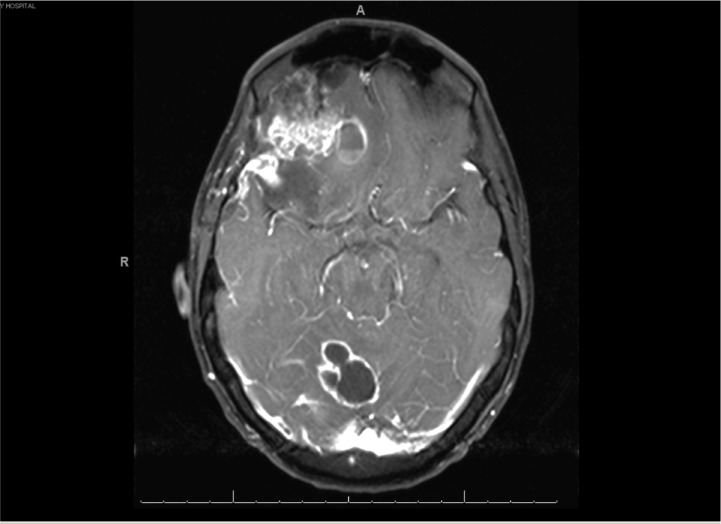

Pathological and imaging findings were consistent with metastatic carcinoma with progressive brain lesions from an unestablished primary focus. At this time the brain lesions were increasingly symptomatic. Further treatment options with chemotherapy and whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) were discussed with the patient. The patient refused palliative intent chemotherapeutic intervention for unknown primary, but agreed to WBRT with a prescribed dose of 30 gray in 10 fractions delivered. Subsequent to this, additional remote pathological consultation with chromosomal analysis revealed isochrome 12p amplications, consistent with a TGCT. Tumor markers with alpha-fetoprotein (aFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (BhCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were not elevated. With evidence supporting the potential for response to chemotherapeutic intervention in TGCT, the patient was started on cisplatin and etoposide, with the plan to include bleomycin in subsequent cycles if his pulmonary function improved [14-16]. Unfortunately the patient’s clinical course consisted of progressive brain metastases (Figure 4), seizures, and pulmonary embolism.

Figure 4. MRI Five Months After Initial Presentation .

Marked progression in a multiple ring-enhancing lesions with vasogenic edema.

He rapidly deteriorated before receiving a full course of treatment and succumbed to his disease only five months after initial presentation. Informed consent was obtained from the patient initially and from the patient's family after he passed away.

Discussion

Literature review

English publications of ‘burned out’ TGCT case reports were identified from Medline and EMBASE databases via OVID engine without restrictions on year of publication. The keywords were “germ cell tumor,” “burned out phenomenon,” and “testicular tumor.” Additional studies were identified from reference lists of retrieved papers and review articles. Studies that did not discuss primary testicular origin were excluded. The search yielded 38 results and each abstract was reviewed. A total of 27 articles were thoroughly reviewed and 79 cases of ‘burned out’ TGCTs were identified. The presenting sites, age of patient, tumor markers, histology, treatments employed, and outcomes were tabulated (Table 1) [5, 7-8, 17-40].

Table 1. Reported Cases of ‘Burned Out’ TGCT.

n = number of cases

aFP = alpha-fetoprotein

BhCG = beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

LDH = lactate dehydrogenase

N = normal level

+ = elevated level

BEP = bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin

RPLND = retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

NR = not reported

NOS = not otherwise specified

| First Author/Citation | Year of Study | Presenting/Metastatic Site | Age of Patient | Tumor Markers | Histology | Treatment | Outcome | ||||||

| Balalaa N [17] | 2011 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 31 | aFP | N | NR | BEP | Treatment response | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Balzer BL [18] | 2006 | Retroperitoneal (n=20) | 17-67 (mean 32) | BhCG | + (n=2) | Seminoma (n=26) | NR | NR | |||||

| Widely disseminated tumor (n=2) | |||||||||||||

| Lung and Liver (n=1) | |||||||||||||

| Mediastinum (n=1) | |||||||||||||

| Other (thyroid, neck thoracic cavity) (n=1) | |||||||||||||

| Testicular mass (n=7) | |||||||||||||

| Castillo C [19] | 2003 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 25 | aFP | + | Mature teratoma | BEP | Initial clinical response | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| Comiter CV [20] | 1995 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 22-36 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Supraclavicular (n=1) | |||||||||||||

| Curigliano G [21] | 2006 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 42 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy, BEP, and RPLND | NR | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Fabre E [5] | 2004 | Testicular (n=1) | 32 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy and Radiotherapy (30Gy) | Free of disease 16 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 35 | aFP | + | Mature teratoma | Orchiectomy, BEP plus vincristine, and RPLND | Free of disease 6 years after the diagnosis | |||||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 50 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy, RPLND, and EP | Total remission 3 years after the diagnosis | |||||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 17 | aFP | N | Mature teratoma | BEP, retroperitoneal mass resection, and orchiectomy | Free of disease 4 years after the diagnosis | |||||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Supraclavicular (n=1) | 39 | aFP | N | Seminoma | BEP followed by salvage chemo (vinblastine, etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin) | Total remission 3 years after the diagnosis | |||||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| George SA [22] | 2015 | GIST (n=1) | 24 | aFP | N | Mixed GCT | Orchiectomy | NR | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Gurioli A [23] | 2013 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 35 | aFP | N | Seminoma | BEP and orchiectomy | Free of disease 2 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 50 | aF | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy, vincristine, ifosfamide, bleomycin, and surgical debulking of mass | Free of disease 4 years after the diagnosis | |||||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| Hu B [24] | 2015 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 37 | aFP | N | Seminoma | NR | NR | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Jaber S [25] | 2010 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 32 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy and surgical removal of the retroperitoneal mass | NR | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| Kebapci M [26] | 2001 | Supraclavicular (n=1) | 22 | aFP | N | GCT having choriocarcinoma and probable embryonal cell carcinoma components | Orchiectomy and BEP | NR | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| Leleu O [27] | 2000 | Pulmonary (n=1) | 30 | aFP | + | Malignant germ cell tumor | Orchiectomy and BEP | Stable 3 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| Lopez JI [28] | 1994 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 20 | aFP | N | Choriocarcinoma | Orchiectomy, biopsy of retroperitoneal masses, BEP plus vincristine | Deceased 7 months after initial complaints | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Mesa H [29] | 2009 | Gastric ulcers (n=1) | 55 | aFP | N | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma- further studies revealed seminoma | Orchiectomy, vincristine, ifosfamide and cisplatin | Free of disease 1 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| Onishi K [30] | 2014 | Para-neoplastic neurological syndrome (n=1) | 41 | NR | Seminoma | Orchiectomy and chemotherapy | Free of disease 15 months after the diagnosis | ||||||

| Patel MD [8] | 2007 | Testicular (n=1) | 23 | aFP | N | Mixed GCT | Orchiectomy | NR | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Perimenis P [31] | 2005 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 40 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy, resection of retroperitoneal mass, and radiotherapy to para-aortic nodes | Free of disease 2 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Peroux E [32] | 2012 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 18 | aFP | + | Non-seminoma NOS | Orchiectomy and chemotherapy | Full remission | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| Preda O [33] | 2011 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 43 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy and chemotherapy | Free of disease 5 months after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Qureshi JM [34] | 2014 | Retroperitoneal and Pulmonary masses (n=1) | 20 | aFP | N | Teratoma GCT | BEP followed by orchiectomy, RPLND, and hepatic mass resection | Free of disease 2 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | + | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Rzeszutko M [35] | 2015 | Spermatic cord (n=1) | 56 | aFP | N | Non-seminoma NOS | Resection of spermatic cord mass | Free of disease 6 months post operatively | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| Sahoo PK [36] | 2013 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 33 | aFP | N | Seminoma vs poorly differentiated carcinoma (seminoma confirmed on IHC) | Orchiectomy and BEP | Patient under observation at time of publication | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | N | ||||||||||||

| Suzuki K [37] | 1998 | Mediastinum (n=1) | 27 | aFP | N | Teratoma GCT and sarcomatous elements | BEP | NR | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| Tasu J [7] | 2003 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 23 | NR | Non-seminoma NOS (n=3) | seminoma (n=2) | Non-seminoma NOS: BEP (n=3) | Metastatic seminoma: radiotherapy and RPLND (n=1) | Seminoma: orchiectomy (n=1) | Complete remission (n=3) | Free of disease after 5 year follow up (n=1) | Free of disease after 7 year follow up (n=1) | |

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 35 | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 50 | ||||||||||||

| Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 17 | ||||||||||||

| Supraclavicular (n=1) | 33 | ||||||||||||

| Yamamoto H [38] | 2007 | Gastric tumor (n=1) | 39 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy and EP | Free of disease 2 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Yucel M [39] | 2009 | Retroperitoneal (n=1) | 28 | aFP | N | ‘Burned out’ testicular tumor NOS | Orchiectomy and BEP | Free of disease 5 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

| LDH | + | ||||||||||||

| Yucel M [40] | 2009 | Prostate (n=1) | 49 | aFP | N | Seminoma | Orchiectomy, BEP plus vincristine, and radiotherapy to mediastinum retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes | Free of disease 7 years after the diagnosis | |||||

| BhCG | N | ||||||||||||

Results

The sites of symptomatic metastasis identified were retroperitoneal (51.9%), testicular (12.7%), mediastinal (3.8%), pulmonary (3.8%), gastric (3.8%), and others (24.1%) consisting of prostate, supraclavicular, head and neck, and widely disseminated. The average patient age at presentation was 32.7 years old. Tumor markers were not found to be consistently elevated, with only 12.7%, 10.2%, and 5.1% of the cases found to be increased for BhCG, aFP, and LDH respectively. The most common treatment employed was orchiectomy with chemotherapy (57.5%), followed by chemotherapy alone (32.5%). Radiation therapy was utilized in four (10%) cases, all of which were seminoma [5,7,31,40]. The majority of reported cases had a good treatment response with only one reported death in the literature [28]. Tabulated case details are summarized in Table 2 [5, 7-8, 17-40].

Table 2. Summary of 'Burned Out' TGCT Cases.

NSGCT= non-seminomatous germ cell tumors

+BhCG= elevated beta-human chorionic gonadotropin level

+aFP= elevated alpha-fetoprotein level

LDH= elevated lactate dehydrogenase level

Orch= orchiectomy

| Presenting Site of 'Burned Out' TGCT | Total Cases | Age (Mean, Range) | +BhCG | +aFP | +LDH | Orch Alone | Chemo Alone | Orch + Chemo | Radiation Therapy Included | Treatment Unknown | Treatment Response, Death, Outcome Unknown | |

| Retroperitoneal | 41 | 32 (17-67) | 4 | 9 | 2 | 21 | 15,1,26 | |||||

| Seminoma | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| NSGCT | ||||||||||||

| Testicular | 10 | 33, (23-56) | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2,0,8 | ||||||

| Seminoma | 1 | |||||||||||

| NSGCT | 2 | 0,0.3 | ||||||||||

| Mediastinum | 3 | 30.3 (27-32) | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Seminoma | ||||||||||||

| NSGCT | 1 | |||||||||||

| Pulmonary | 3 | 27.3 (20-32) | 2 | 2,0,1 | ||||||||

| Seminoma | ||||||||||||

| NSGCT | 2 | |||||||||||

| Gastric | 3 | 39 (24-55) | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Seminoma | 2 | |||||||||||

| NSGCT | ||||||||||||

| Other | 19 | 32 (20-49) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 4,0,13 | |||||

| Seminoma | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| NSGCT | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Total | 79 | 32.7 (17-67) | 10 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 16 | 4 | 38 | 23,1,51 | |

| Seminoma | 0 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| NSGCT | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Other/unknown | 2 | |||||||||||

Case discussion

A salient feature of all invasive TGCTs is a gain in material in the short arm of chromosome 12, and is diagnostic if present [41]. Although the initial pathology revealed a non-diagnostic metastatic tumor, further testing revealed an amplification of chromosome 12p leading to the diagnosis of TGCT. This suggests that the examination of poorly differentiated carcinomas of an unknown primary site using light microscopy and immunohistochemical profiling may be inadequate, and should undergo additional testing modalities with molecular chromosomal analysis [41-42].

The behavior and aggressive nature of the tumor discussed throughout this case combines the complexity of the evolving field of tumor biology and unique patient characteristics. Interestingly, the patient had a confirmed family history of factor V Leiden mutation. It has been suggested that clotting factor polymorphisms such as factor V Leiden are associated with cancer onset and progression. The theoretical mechanism behind such adverse effects stems from the involvement of tissue factor and thrombin in tumor angiogenesis, which is essential for tumor growth and metastasis [43]. Furthermore, such factors may contribute to a more radio-resistant tumor profile despite advanced diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities. Thus, this case reflects the arising need for further research to explore the dynamic interplay of tumor biology and patient characteristics for targeting tumor response.

Conclusions

This case is presented for its unconventional presentation, rarity of occurrence, and difficulty in diagnosis. It brings forward the discussion of both the commonality of TGCT in young male adults, as well as the anomaly of a ‘burned out’ TGCT. With unreliable tumor markers, nonspecific symptoms, and pathological findings, the ‘burned out’ phenomenon accounts for a challenging diagnosis, particularly with the presenting symptom arising from a less common metastatic site. This case adds to the increasing literature on the rare entity of the ‘burned out’ TGCT, and upon literature review, presents itself as the first reported case presenting with brain metastasis. By establishing a strong foundation of ‘burned out’ TGCT in the literature leading to familiarity of the diagnostic process, a deeper understanding into medical management may arise.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent for the use of case details with intent of publication was obtained from the individual described in the case study. Consent was discussed and documented by the first author of the case report. As the patient unfortunately was deceased at the time of publication, further written consent was also obtained by the family of the patient.

References

- 1.International germ cell consensus classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result Program: SEER stat fact sheets: testis cancer. National Cancer Institute. [Sep;2015 ];http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/testis.html National Cancer Institute. 2015

- 3.Trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Sigurdson AJ, Brown LM, Tsao L, Tarone RE. Cancer. 2003;97:63–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. N Engl J Med. Vol. 337. AUA Washington, DC: 1997. Testicular germ-cell cancer; pp. 242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.'Burned-out' primary testicular cancer. Fabre E, Jira H, Izard V, Ferlicot S, Hammoudi Y, Theodore C, Di Palma M, Benoit G, Droupy S. BJU Int. 2004;94:74–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesions of testes observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. The significance and genesis of hematoxylin-staining bodies in the human testis. Azzopardi JG, Mostofi FK, Theiss EA. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1945003/ Am J Pathol. 1961;38:207–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imaging of burned-out testis tumor: five new cases and review of the literature. Tasu J, Faye N, Eschwege P, Rocher L, Bléry M. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:515–521. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging appearance of a burned-out testicular germ cell neoplasm. Patel MD, Patel BM. http://www.jultrasoundmed.org/content/26/1/143.short. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:143–146. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Primary extragonadal germ cell tumors of the retroperitoneum: differentiation of primary and secondary tumors. Choyke PL, Hayes WS, Sesterhenn IA. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Choyke+PL%2C+Hayes+WS%2C+Sesterhenn+IA%3A+Primary+extragonadal+germ+cell+tumors+of+the+retroperitoneum%3A+differentiation+of+primary+and+secondary+tumors. Radiographics. 1993;13:1365–1375. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.6.8290730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis of an infraclinical testicular seminoma (author's transl). [Article in French] Savatovsky I, Paugam B, Piekarski JD. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/7264354. J Urol (Paris) 1981;87:235–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Primary or secondary extragonadal germ cell tumors? Bohle A, Studer UE, Sonntag RW, Scheidegger JR. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3007784. J Urol. 1986;135:939–943. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Extragonadal germ cell tumors: clinical presentation and management. Albany C, Einhorn LH. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Albany+C%2C+Einhorn+LH%3A+Extragonadal+germ+cell+tumors%3A+clinical+presentation+and+management. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:261–265. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835f085d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curing metastatic testicular cancer. Einhorn LH. Proc Natl Aca Sc USA. 2002;99:4592–4595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072067999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chemotherapy of disseminated testicular cancer. a random prospective study. Einhorn L, Williams S. Cancer. 1980;46:1339–1344. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800915)46:6<1339::aid-cncr2820460607>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.First-line high-dose chemotherapy +/- radiation therapy in patients with metastatic germ-cell cancer and brain metastases. Kollmannsberger C, Nichols C, Bamberg M, Hartmann JT, Schleucher N, Beyer J, Schöfski P, Derigs G, Rüther U, Böhlke I, Schmoll HJ, Kanz L, Bokemeyer C. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:553–559. doi: 10.1023/a:1008388328809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treatment of brain metastases in patients with testicular cancer. Bokemeyer C, Nowak P, Haupt A, Metzner B, Köhne H, Hartmann JT, Kanz L, Schmoll HJ. http://jco.ascopubs.org/content/15/4/1449.short. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1449–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burned-out testicular tumor: a case report. Balalaa N, Salman M, Hassen W. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4:12–15. doi: 10.1159/000324041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spontaneous regression of testicular germ cell tumors: an analysis of 42 cases. Balzer BL, Ulbright TM. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:858–865. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209831.24230.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gastrointestinal bleeding as the first manifestation of a burned-out tumour of the testis. Castillo C, Krygier G, Carzoglio J, Cepellini Magariños R, Cepellini Olmos R, Jubín J, Sabini G. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7:458–463. doi: 10.1007/BF02716597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nonpalpable intratesticular masses detected sonographically. Comiter CV, Benson CJ, Capelouto CC, Kantoff P, Shulman L, Richie JP, Loughlin KR. J Urol. 1995;154:1367–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21."Burned out" phenomenon of the testis in retroperitoneal seminoma. Curigliano G, Magni E, Renne G, De Cobelli O, Rescigno M, Torrisi R, Spitaleri G, Pietri E, De Braud F, Goldhirsch A. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:335–336. doi: 10.1080/02841860500401175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Retrogressed (burned-out) testicular germ cell tumor disguising as duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. George SA, Al-Taleb A, Hussein S. Onc Gas Hep Rep. 2015;4:114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Two cases of retroperitoneal metastasis from a completely regressed burned-out testicular cancer. Gurioli A, Oderda M, Vigna D, Peraldo F, Giona S, Soria F, Cassenti A, Pacchioni D, Gontero P. Urologia. 2013;80:74–79. doi: 10.5301/RU.2013.10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu B, Shah S, Shojaei S, Daneshmand S. Clin Genitourin Cancer. Vol. 13. Association, AUA New Orleans, LA: 2015. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection as first-line treatment of node-positive seminoma; pp. 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Retroperitoneal mass and burned out testicular tumor. Jaber S. http://www.sjkdt.org/article.asp?issn=1319-2442;year=2010;volume=21;issue=3;spage=542;epage=543;aulast=Jaber. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:542–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burned-out tumor of the testis presenting as supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. Kebapci M, Can C, Isiksoy S, Aslan O, Oner U. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:371–373. doi: 10.1007/s003300101038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulmonary metastasis secondary to burned-out testicular tumor. Leleu O, Vaylet F, Debove P, Levagueresse R, L'her P. Respiration. 2000;67:590. doi: 10.1159/000029579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burned-out tumour of the testis presenting as retroperitoneal choriocarcinoma. Lopez JI, Angulo JC. Int Urol Nephrol. 1994;26:549–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02767657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29."Burned out" testicular seminoma presenting as a primary gastric malignancy. Mesa H, Rawal A, Rezcallah A, Iwamoto C, Niehans GA, Druck P, Gupta P. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:74–77. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burned-out testicular tumor diagnosed triggered by paraneoplastic neurological syndrome; a case report (Article in Japanese) Onishi K, Tomioka A, Maruyama Y, Otani T, Ishikawa H, Fujimoto K. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/25602484. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2014;60:651–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Retroperitoneal seminoma with 'burned out' phenomenon in the testis. Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Geraghty J, Macdonagh R. Int J Urology. 2005;12:115–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burned-out tumour: a case report. Peroux E, Thome A, Geffroy Y, Guema BN, Arnaud FX, Teriitehau CA, Baccialone J, Potet J. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93:796–798. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Retroperitoneal seminoma as a first manifestation of a partially regressed (burnt-out) testicular germ cell tumor. Preda O, Nicolae A, Loghin A, Borda A, Nogales FF. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Preda+O%2C+Nicolae+A%2C+Loghin+A%2C+Borda+A%2C+Nogales+FF%3A+Retroperitoneal+seminoma+as+a+first+manifestation+of+a+partially+regressed+(burnt-out)+testicular+germ+cell+tumor. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metastatic "burned-out" germ cell tumor of the testis. Qureshi JM, Feldman M, Wood H. J Urol. 2014;192:936–937. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paratesticular localization of burned out non-seminomatous germ cell tumor--NSGCT: a case report. Rzeszutko M, Rzeszutko W, Nienartowicz E, Jeleń M. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Rzeszutko+M%2C+Rzeszutko+W%2C+Nienartowicz+E%2C+Jele%C5%84+M%3A+Paratesticular+localization+of+burned+out+non-seminomatous+germ+cell+tumor--NSGCT%3A+a+case+report. Pol J Pathol. 2006;57:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burned out seminomatous testicular tumor with retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis: a case report. Sahoo PK, Mandal PK, Mukhopadhyay S, Basak SN. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4:390–392. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Growing mediastinal metastatic tumour in a patient with burned out testicular cancer. Suzuki K, Yoshida T, Inoue M, Yoshida I, Kurokawa K, Suzuki T, Imai K, Yamanaka H. Int Urol Nephrol. 1998;30:181–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02550574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a rare extragonadal presentation of seminoma of testis. Yamamoto H, Deshmukh N, Gourevitch D, Taniere P, Wallace M, Cullen MH. Int J Urol. 2007;14:261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burned-out testis tumour that metastasized to retroperitoneal lymph nodes: a case report. Yucel M, Kabay S, Saracoglu U, Yalcinkaya S, Hatipoglu NK, Aras E. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7266. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burned-out testicular seminoma that metastasized to the prostate. Yucel M, Saracoglu U, Yalcinkaya S, Hatipoglu NK, Kabay S, Dedekarginoglu G. http://web.b.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=05007208&AN=47691253&h=WI0%2fk26SVDsZUMIbi1v8IYC1BZ2h2o1xbzBxlYgJwYnJACEIyLRmHxQdw5WrOhILrWOfXR66S5fkmk9DBNL4ZQ%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d05007208%26AN%3d47691253 Cent European J Urol. 2009;62:195–197. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Expression profile of genes from 12p in testicular germ cell tumors of adolescents and adults associated with i(12p) and amplification at 12p11.2-p12.1. Rodriguez S, Jafer O, Goker H, Summersgill BM, Zafarana G, Gillis AJ, van Gurp RJ, Oosterhuis JW, Lu YJ, Huddart R, Cooper CS, Clark J, Looijenga LH, Shipley JM. Oncogene. 2003;22:1880–1891. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poorly differentiated neoplasms of unknown primary site. [Aug;2015 ];http://www.aboutcancer.com/cup_poor_neo_utd_507.htm. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s40291-015-0133-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Clotting factor gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk. Vossen CY, Hoffmeister M, Chang-Claude JC, Rosendaal FR, Brenner H. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1722–1727. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]