Abstract

Purpose

Obesity, insulin resistance, and elevated levels of circulating proinflammatory mediators are associated with poorer prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. To investigate whether white adipose tissue (WAT) inflammation represents a potential unifying mechanism, we examined the relationship between breast WAT inflammation and the metabolic syndrome and its prognostic importance.

Experimental Design

WAT inflammation was defined by the presence of dead/dying adipocytes surrounded by macrophages forming crown-like structures of the breast (CLS-B). Two independent groups were examined in cross-sectional (Cohort 1) and retrospective (Cohort 2) studies. Cohort 1 included 100 women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer risk reduction (n=10) or treatment (n=90). Metabolic syndrome-associated circulating factors were compared by CLS-B status. The association between CLS-B and the metabolic syndrome was validated in Cohort 2 which included 127 women who developed metastatic breast cancer. Distant recurrence free survival (dRFS) was compared by CLS-B status.

Results

In Cohorts 1 and 2, breast WAT inflammation was detected in 52/100 (52%) and 52/127 (41%) patients, respectively. Patients with breast WAT inflammation had elevated insulin, glucose, leptin, triglycerides, C-reactive protein, and interleukin-6; and lower HDL cholesterol and adiponectin (P<0.05) in Cohort 1. In Cohort 2, breast WAT inflammation was associated with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes (P<0.05). Compared to patients without breast WAT inflammation, the adjusted hazard ratio for dRFS was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.07 to 3.13) for patients with inflammation.

Conclusions

WAT inflammation, a clinically occult process, helps to explain the relationship between metabolic syndrome and worse breast cancer prognosis.

Keywords: obesity, insulin, white adipose tissue, inflammation, metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Obesity is a cause of chronic inflammation with a rapidly rising global prevalence (1). Chronic inflammation is associated with the development and progression of a number of common epithelial malignancies (2-5). Defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater, obesity is now a leading modifiable contributor to breast cancer mortality worldwide (6-9). Specifically, obesity is associated with increased risk of relapse and decreased overall survival for patients with early-stage breast cancer (10-15). However, specific strategies that target obesity have been limited by an incomplete understanding of the complex biologic mechanisms underlying the obesity-cancer relationship. There is growing evidence that inflammation is a central mechanism through which obesity promotes cancer progression via local effects in the tumor microenvironment as well as systemic effects in the host (1-3, 7). Moreover, chronic inflammation appears to play a pathogenic role in atherosclerosis, diabetes, and other conditions associated with the metabolic syndrome – a group of disorders that includes obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and fasting hyperglycemia (16-19). For patients with breast cancer, the metabolic syndrome is associated with worse prognosis (20). Identification of specific pathophysiology linking the metabolic syndrome and its components to adverse breast cancer outcomes could lead to the development of more effective, mechanism-based therapeutic strategies for this high risk population (21).

Chronic inflammation of visceral white adipose tissue (WAT) occurs in the majority of obese individuals (16, 17). This inflammation is histologically detectable by the identification of crown-like structures (CLS), which are comprised of a dead or dying adipocyte surrounded by macrophages. Visceral WAT inflammation, manifested as CLS, is associated with increased levels of proinflammatory mediators that promote the development of insulin resistance and diabetes – both predict poorer survival for patients with breast cancer (16, 22, 23). Within the breast, WAT inflammation detected by CLS (CLS-B) is present in 90% of obese patients and is associated with the postmenopausal state (24-26). Notably, breast WAT inflammation is also present in a smaller proportion of the non-obese (25). The presence of breast WAT inflammation is associated with activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor that activates expression of proinflammatory mediators, and increased levels of aromatase, the rate-limiting enzyme for estrogen biosynthesis (24). Thus, breast WAT inflammation occurs in association with a number of tissue level alterations that may confer worse prognosis for patients with breast cancer. Furthermore, we recently reported that breast WAT inflammation is an indicator of diffuse WAT inflammation, occurring synchronously in distant fat depots such as abdominal subcutaneous fat (25). This observation suggests that breast WAT inflammation is a sentinel of a clinically occult, diffuse, low grade inflammatory process. We therefore investigated whether breast WAT inflammation is associated with specific circulating factors as well as clinical features of the metabolic syndrome. We also explored the prognostic importance of breast WAT inflammation on clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

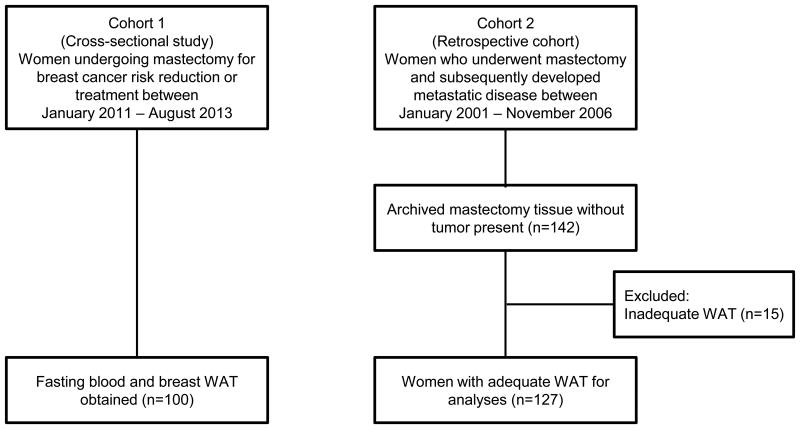

Patients enrolled in two independent cohorts were examined (Fig 1). Cohort 1 included 100 women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer risk reduction or treatment between January 2011 and August 2013 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York, USA. Non-tumor containing breast WAT and fasting blood specimens were prospectively collected at the time of surgery. Cohort 2 included women who underwent mastectomy between January 2001 and November 2006 for stage I-III breast cancer and developed distant metastatic disease within follow-up through 2014. From the institutional database, 142 patients who developed pathologically confirmed metastatic disease after index mastectomy were identified. Of these, 15 patients were excluded due to inadequate WAT available for CLS-B analyses. Thus, a total of 127 patients were included in Cohort 2. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of MSKCC.

Figure 1. Study flow and tissue availability in Cohort 1 and Cohort 2.

Clinical Data and Biospecimen Collection

Clinicopathologic data were abstracted from the electronic medical record (EMR). Height and weight recorded on the day of surgery were used to calculate BMI as kg/m2. Standard definitions were used to categorize BMI as under- or normal weight (BMI< 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Menopausal status was categorized as either premenopausal or postmenopausal based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) criteria (27). Tumor (T) and nodal (N) staging was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer stage of disease classification. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) were categorized as positive if >1% staining by immunohistochemistry (IHC) was reported. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) was categorized as positive or negative based on American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) joint guidelines (positive if IHC 3+ or FISH-amplification ≥ 2.0) (28). Use of adjuvant therapy, date and location of recurrence, and date and cause of death were obtained from the EMR. Vital status data in the EMR is linked with state and national death certificate registries and the Social Security Death Index. If alive, last follow-up date was recorded. The STEEP criteria were used to define distant relapse free survival (dRFS) as appearance of distant recurrence or death from breast cancer or other causes (29).

In Cohort 1, five formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were prepared on the day of mastectomy from breast WAT not involved by tumor. Additionally, a 30 mL fasting blood sample was obtained preoperatively on the day of surgery. Blood was separated into serum and plasma by centrifugation within 3 hours of collection and stored at -80° C.

In Cohort 2, representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections were reviewed to select an appropriate FFPE block from the mastectomy specimen. The block that contained the most WAT was selected by the study pathologist (DG).

Tissue Assessment

Breast WAT inflammatory status was categorized as inflamed or non-inflamed according to the presence or absence of CLS-B. When 5 FFPE blocks were available, 1 section was obtained from each block. When 1 FFPE block was available, 5 sections were obtained at 50 μm intervals (5 μm thick and approximately 2 cm in diameter). Thus a total of 5 breast WAT sections were obtained per patient. All sections were immunostained for CD68, a macrophage marker (mouse monoclonal KP1 antibody; Dako; dilution 1:4,000), as previously described (24, 25). The anti-CD68 stained sections were examined by the study pathologist using light microscopy to detect and record the presence or absence of CLS-B. To determine the total WAT area examined, exclusive of epithelial and fibrotic tissues, digital photographs of each slide were generated and measured with Image J Software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Cases with inadequate CD68-immunostained WAT area were excluded from analysis.

Blood Measurements

Plasma levels of glucose (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA) and insulin (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden), as well as leptin, adiponectin, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and interleukin-6 (IL-6; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Serum levels of total, HDL, and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in the clinical chemistry laboratory at MSKCC. Coefficients of variation for intra-assay variation for quality control samples were less than 7%.

Statistical Analyses

For continuous variables, the difference between CLS-B positive and CLS-B negative patients was examined using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were examined using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. In an exploratory analysis, Cox proportional hazards regression was used for univariate and multivariate analyses to examine the association between CLS-B and dRFS. Probability of dRFS in subjects with and without CLS-B was summarized via the Kaplan-Meier method. For the multivariate model, covariates of interest were identified as those with trend of univariate associations (P<0.25) with the outcomes of interest or known prognostic factors. The final multivariate model was adjusted for the following covariates: age, race, BMI, breast cancer subtype, grade, stage, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and adjuvant therapy. For all analyses, statistical significance was set at two-tailed P<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Cohort 1: Breast WAT inflammation and circulating factors

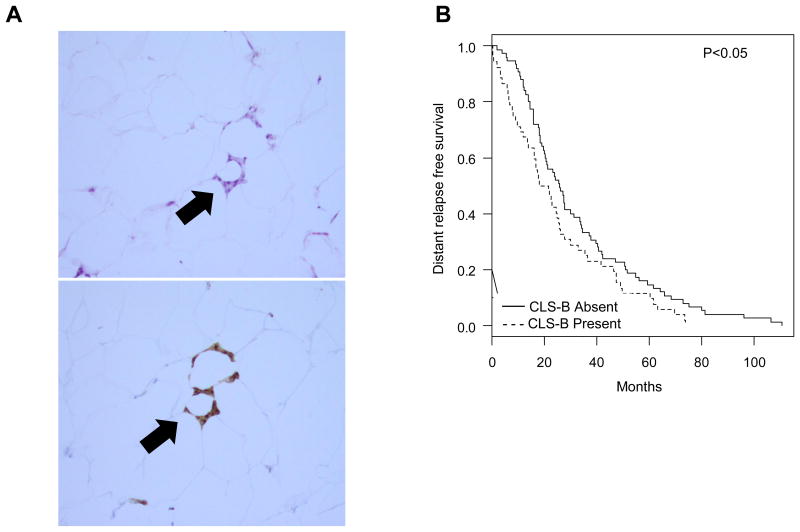

Baseline characteristics stratified by breast WAT inflammation (CLS-B) status are shown in Table 1. CLS-B were detected in 52 of 100 (52%) patients (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. S1). Table 2 shows circulating factors stratified according to CLS-B status. Presence of CLS-B was associated with elevated levels of glucose (P=0.01), insulin (P=0.03), leptin (P<0.001), and triglycerides (P<0.001), and nonsignificant elevations in total cholesterol (P=0.15) and LDL cholesterol (P=0.06). Of note, 11 women were on statin therapy at the time of assessment. Presence of CLS-B was associated with significantly lower levels of HDL cholesterol (P=0.003) and adiponectin (P<0.001). In addition, CLS-B was associated with elevated levels of the inflammatory factors hsCRP (P<0.001) and IL-6 (P<0.001). In this cohort, presence of CLS-B was associated with a clinical diagnosis of dyslipidemia (P<0.001, Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical features of Cohort 1.

| Variables | CLS-B Negative (n=48) | CLS-B Positive (n=52) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 45 (31 to 62) | 49 (27 to 70) | 0.01 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 43 (90%) | 42 (82%) | |

| Black | 2 (4%) | 5 (10%) | |

| Asian | 3 (6%) | 4 (8%) | 0.68 |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.49 |

| BMI | |||

| Median (range) | 23.2 (17.5 to 31.4) | 27.3 (18.4 to 50.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI category, n(%) | |||

| Normal | 31 (65%) | 17 (33%) | |

| Overweight | 16 (33%) | 17 (33%) | |

| Obese | 1 (2%) | 18 (34%) | <0.001 |

| Menopausal Status, n (%) | |||

| Pre | 39 (81%) | 26 (50%) | |

| Post | 9 (19%) | 26 (50%) | 0.002 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | |||

| No | 47 (98%) | 38 (73%) | |

| Yes | 1 (2%) | 14 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |||

| No | 45 (94%) | 43 (83%) | |

| Yes | 3 (6%) | 9 (17%) | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | |||

| No | 48 (100%) | 48 (92%) | |

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: CLS-B, crown-like structures of the breast; BMI, body mass index

Figure 2. White adipose tissue inflammation and breast cancer recurrence.

A. H&E (upper panel) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (lower panel) showing CLS-B (100×). B. Kaplan-Meier curve for distant relapse free survival by CLS-B status in women with recurrent, metastatic breast cancer (n=127). CLS-B, crown-like structures of the breast.

Table 2. Measured blood variables in Cohort 1.

| Variable | CLS-B Negative (n=48) | CLS-B Positive (n=52) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 72 (67 to 77) | 80 (70 to 84) | 0.01 |

| Insulin (mU/L) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.1 (3.4 to 5.0) | 4.8 (3.7 to 7.2) | 0.03 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 190 (165 to 213) | 199 (176 to 224) | 0.15 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 103 (84 to 128) | 114 (97 to 140) | 0.06 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 70 (62 to 81) | 59 (50 to 70) | 0.003 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 66 (56 to 79) | 93 (68 to 122) | <0.001 |

| Leptin (pg/ml) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7.9 (5.5 to 15.5) | 17.4 (9.6 to 27.9) | <0.001 |

| Adiponectin (μg/ml) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 13.3 (10.9 to 16.3) | 9.9 (7.0 to 12.2) | <0.001 |

| hsCRP (ng/ml) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.51 (0.32 to 1.04) | 1.06 (0.66 to 3.04) | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.75 (0.46 to 1.10) | 1.26 (0.72 to 2.31) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6

Cohort 2: Breast WAT inflammation and clinical components of the metabolic syndrome

To confirm and extend findings from Cohort 1, associations between CLS-B and cardiometabolic disorders were examined in a second, independent cohort. Clinical characteristics by CLS-B status are presented in Table 3. The presence of CLS-B was associated with clinical features of the metabolic syndrome including hyperlipidemia (P=0.04), hypertension (P=0.02), and diabetes (P=0.003).

Table 3. Clinicopathologic features of Cohort 2.

| Characteristic | CLS-B Negative (n = 75) | CLS-B Positive (N = 52) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 44 (32 to 78) | 54 (35 to 84) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 66 (88%) | 40 (77%) | |

| Black | 7 (9%) | 10 (19%) | |

| Asian | 2 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 0.19 |

| BMI | |||

| Median (range) | 25.3 (17.6 to 45.3) | 30.1 (19.9 to 50.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI category, n (%) | |||

| Normal or Underweight | 33 (44%) | 10 (19%) | |

| Overweight | 29 (39%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Obese | 13 (17%) | 28 (54%) | <0.001 |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||

| Pre | 47 (63%) | 18 (35%) | |

| Post | 28 (37%) | 34 (65%) | 0.002 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | |||

| No | 68 (91%) | 40 (77%) | |

| Yes | 7 (9%) | 12 (23%) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |||

| No | 63 (84%) | 34 (65%) | |

| Yes | 12 (16%) | 18 (35%) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | |||

| No | 73 (97%) | 42 (81%) | |

| Yes | 2 (3%) | 10 (19%) | 0.003 |

| T size, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 2 cm | 25 (33%) | 17 (33%) | |

| > 2 – 5 cm | 25 (33%) | 21 (40%) | |

| > 5 cm | 25 (33%) | 14 (27%) | 0.65 |

| Lymph node status, n (%) | |||

| N0 | 11 (15%) | 20 (38%) | |

| N+ | 64 (85%) | 32 (62%) | 0.003 |

| Tumor receptor status, n (%) | |||

| ER+/HER2– | 43 (57%) | 30 (58%) | |

| HER2+ | 12 (16%) | 11 (21%) | |

| Triple negative | 20 (27%) | 11 (21%) | 0.66 |

| Grade, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | |

| 2 | 10 (14%) | 6 (12%) | |

| 3 | 59 (86%) | 44 (86%) | 0.58 |

| Missing | 6 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 0.24 |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| Ductal | 64 (85%) | 46 (88%) | |

| Lobular | 8 (11%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Mixed | 3 (4%) | 4 (8%) | 0.30 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy, n (%) | |||

| No | 22 (29%) | 23 (44%) | |

| Yes | 53 (71%) | 29 (56%) | 0.093 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |||

| No | 8 (11%) | 17 (33%) | |

| Yes | 67 (89%) | 35 (67%) | 0.003 |

| Adjuvant anti-HER2 therapy, n (%) | |||

| No | 69 (92%) | 49 (94%) | |

| Yes | 6 (8%) | 3 (6%) | 0.736 |

| Adjuvant aromatase inhibitor or tamoxifen, n (%) | |||

| No | 30 (40%) | 21 (40%) | |

| Yes | 45 (60%) | 31 (60%) | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2;

Breast WAT inflammation and distant recurrence free survival

Median follow-up time was 50 (1 to 116) months. Median time to dRFS was 23 months (range 0.3 to 111). During this period, a total of 99 breast cancer deaths were observed. There were no differences in pathologic prognostic features between CLS-B positive versus CLS-B negative patients, except that there was a higher prevalence of axillary lymph node involvement at index mastectomy in CLS-B negative patients (P=0.003, Table 3). In univariate analysis, median dRFS was 20 months (range 16 to 26) in patients with CLS-B compared to 26 months (range 20 to 34) in patients without CLS-B (hazard ratio [HR] 1.44, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.06, P<0.05; Fig. 2B). The relationship between presence of CLS-B and shortened dRFS remained significant in the multivariate model (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.07 to 3.13, P=0.03).

Discussion

In this study, breast WAT inflammation, defined by the presence of CLS-B, was associated with circulating factors characteristic of the metabolic syndrome. Specifically, breast WAT inflammation was associated with hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. Breast WAT inflammation was also associated with elevated circulating levels of hsCRP and IL-6. The association between breast WAT inflammation and features of the metabolic syndrome was confirmed in a second, independent cohort. In an exploratory investigation, the presence of breast WAT inflammation at breast cancer diagnosis was associated with a 6 month shorter dRFS in women who developed metastatic disease. When controlled for other prognostic factors including BMI, breast WAT inflammation was an independent predictor of shortened dRFS in this population.

Our findings support the role of WAT inflammation in breast cancer progression. We previously reported that breast WAT inflammation occurs in the majority (90%) of obese women (24, 25). Additionally, WAT inflammation is associated with activation of NF-κB and increased levels of aromatase in breast tissue (24, 30). Moreover, breast WAT inflammation is an indicator of diffuse adipose inflammation (25, 31). In the current study, we detected biochemical changes characteristic of the metabolic syndrome in patients with breast WAT inflammation. Specifically, these patients had higher fasting insulin and glucose levels than those without breast WAT inflammation. Patients with breast WAT inflammation also had higher circulating levels of triglycerides and lower HDL cholesterol than those without inflammation. These associations were detectable despite the inclusion of statin users. In addition, patients who had one or more metabolic syndrome conditions had a higher frequency of breast WAT inflammation. These findings tie together a number of previously reported observations in the following manner: First, the metabolic syndrome and its components are associated with worse breast cancer-specific outcomes (20, 22, 23, 32, 33). Second, elevated circulating levels of IL-6 and CRP are associated with shortened disease-specific and overall survival in patients with breast cancer (34-36). Third, elevated leptin and low adiponectin levels are both associated with adverse breast cancer outcomes (32, 37). In our study, breast WAT inflammation was associated with higher circulating levels of leptin and lower adiponectin levels. Taken together, these data suggest that WAT inflammation helps to explain the link between metabolic syndrome and worse breast cancer prognosis.

Based on our finding that breast WAT inflammation is associated with alterations in systemic factors that are each independently known to confer worse breast cancer prognosis, we explored whether breast WAT inflammation is associated with clinical outcomes in patients developing metastatic breast cancer. We observed an association between breast WAT inflammation at the time of index mastectomy and decreased dRFS. Notably, the relationship between breast WAT inflammation and shortened dRFS emerged in our study despite a higher proportion of women without breast WAT inflammation having axillary lymph node involvement at diagnosis, further supporting the role of breast WAT inflammation as an independent prognostic factor. The relationship between breast WAT inflammation and inferior dRFS remained significant after adjusting for BMI. This finding suggests that the presence of breast WAT inflammation may provide clinically relevant information beyond that provided by BMI. It is increasingly recognized that some phenotypically obese individuals, defined by elevated BMI, are metabolically healthy (38-40), while metabolic obesity, including insulin resistance, can occur in others despite a normal BMI (41, 42). Consistent with these observations, breast WAT inflammation occurs in approximately one-third of women with normal BMI (25). Hence, breast WAT inflammation may be a stronger predictor of breast cancer outcomes than BMI and warrants further study. A critical step for future studies would be the development of a blood-based signature that detects WAT inflammation. A blood assay that indicates the presence of WAT inflammation could prove useful for assessing both risk and prognosis.

The mechanisms by which obesity and, more broadly, the metabolic syndrome promote breast cancer progression involve multiple biologic pathways (7). In the breast, obesity is associated with chemokine-mediated macrophage recruitment leading to angiogenesis and contributing to a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment (43). Systemically, altered adipokine levels, including low adiponectin and elevated leptin concentrations, promote cell proliferation and survival (44-46). Insulin can stimulate the synthesis of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and both can activate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MAPK pathways which are linked to tumor progression (47-49). Thus, strategies that target insulin signaling and thereby impact breast cancer outcomes are currently under study (50). However, as insulin resistance represents only one component of the metabolic syndrome, alternate therapeutic approaches may be clinically useful. Targeting WAT inflammation, which is associated with systemic alterations in levels of insulin, lipids, and inflammatory mediators, could represent a more comprehensive approach.

While the design of this study is strengthened by prospective collection of paired breast tissue and fasting blood from volunteer patients, it is limited by a retrospective, single institution exploration of a prognostic effect of breast WAT inflammation. Nonetheless, this is to our knowledge the first demonstration of an association between adipose inflammation in the breast and a worse clinical course in patients who developed metastatic breast cancer, and the association is supported by the observed changes in levels of circulating factors. Larger prospective longitudinal studies are needed to comprehensively investigate the prognostic role of breast WAT inflammation together with its associated circulating abnormalities to confirm these findings. The development of a blood biomarker signature of WAT inflammation would facilitate larger and more efficient multi-center studies evaluating breast cancer outcomes as they relate to obesity, inflammation, and the metabolic syndrome. Another future direction would be to evaluate the role of WAT inflammation in other obesity-related cancers.

In conclusion, breast WAT inflammation is associated with systemic metabolic and proinflammatory abnormalities and a worse clinical course in patients that develop metastatic breast cancer. These findings support additional study of WAT inflammation as a possible target for intervention in early-stage breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1. White adipose tissue inflammation. A. CLS-B positive breast WAT. H&E (upper panel) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (lower panel); 40× (left panel) and 400× (right panel). Arrow indicates CLS-B. B. CLS-B negative breast WAT. H&E (upper panel) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (lower panel); 40× (left panel) and 400× (right panel). WAT, white adipose tissue; CLS-B, crown-like structures of the breast.

Translational Relevance.

The metabolic syndrome and its components such as obesity are associated with worse breast cancer prognosis. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms is necessary to develop strategies to improve outcomes in this high risk population. We previously reported that breast white adipose tissue (WAT) inflammation occurs in most obese individuals and is associated with increased levels of aromatase. Here we show that breast WAT inflammation, a clinically occult condition, is associated with the metabolic syndrome and related changes in circulating levels of metabolic and proinflammatory factors. Importantly, breast WAT inflammation was also associated with a worse clinical course for patients who develop metastatic breast cancer. These findings support further study of WAT inflammation as a potential target for intervention in early-stage breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by grants and contracts NIH/NCI HHSN2612012000181 and NIH/NCI R01CA154481 (to A.J. Dannenberg), UL1TR000457 of the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College (to N.M. Iyengar and X. K. Zhou), 2013 Conquer Cancer Foundation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Young Investigator Award (to N.M. Iyengar), the Botwinick-Wolfensohn Foundation (in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Botwinick; to A.J. Dannenberg), MSKCC Center for Metastasis Research (to C.A. Hudis), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to A.J. Dannenberg and C.A. Hudis), and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748). LWJ is supported by grants from the NCI.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Presentations: This work was presented in part as an oral abstract at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

References

- 1.Howe LR, Subbaramaiah K, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Molecular Pathways: Adipose Inflammation as a Mediator of Obesity-Associated Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:6074–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyengar NM, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Obesity and inflammation: new insights into breast cancer development and progression. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book / ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting . 2013:46–51. doi: 10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar NM, Morris PG, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Obesity, Inflammation, and Breast Cancer. In: Dannenberg AJ, Berger NA, editors. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. New York: Springer; pp. 2013pp. 181–217. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi J, Segal LM, Laurent R, Lang A, Rayburn J. F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America's Future 21012. 2012 [cited 2012 09/28/2012]; Available from: http://healthyamericans.org/assets/files/TFAH2012FasInFatFnlRv.pdf.

- 7.Iyengar NM, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Obesity and cancer: local and systemic mechanisms. Annual review of medicine. 2015;66:297–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050913-022228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calle EE, Thun MJ. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:6365–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. The oncologist. 2010;15:556–65. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewertz M, Jensen MB, Gunnarsdottir KA, Hojris I, Jakobsen EH, Nielsen D, et al. Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:25–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;2010:23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrelli JM, Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ. Body mass index, height, and postmenopausal breast cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2002;13:325–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1015288615472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majed B, Moreau T, Senouci K, Salmon RJ, Fourquet A, Asselain B. Is obesity an independent prognosis factor in woman breast cancer? Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;111:329–42. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sparano JA, Zhao F, Martino S, Ligibel JA, Perez EA, Saphner T, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of the E1199 Phase III Trial Evaluating the Role of Taxane and Schedule in Operable Breast Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annual review of physiology. 2010;72:219–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014;156:20–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators of inflammation. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/289645. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berrino F, Villarini A, Traina A, Bonanni B, Panico S, Mano MP, et al. Metabolic syndrome and breast cancer prognosis. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2014;147:159–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3568–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Madarnas Y, et al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Heath DD, et al. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:54–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris PG, Hudis CA, Giri D, Morrow M, Falcone DJ, Zhou XK, et al. Inflammation and increased aromatase expression occur in the breast tissue of obese women with breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1021–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iyengar NM, Morris PG, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Giri D, Harbus MD, et al. Menopause is a determinant of breast adipose inflammation. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:349–58. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun X, Casbas-Hernandez P, Bigelow C, Makowski L, Joseph Jerry D, Smith Schneider S, et al. Normal breast tissue of obese women is enriched for macrophage markers and macrophage-associated gene expression. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;131:1003–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v.2.2011. 2011 [cited 2009; Available from: www.nccn.org.

- 28.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M, McShane LM, Allison KH, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, Gray RJ, Pritchard KI, Chapman JA, et al. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP system. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2127–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbaramaiah K, Morris PG, Zhou XK, Morrow M, Du B, Giri D, et al. Increased levels of COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 contribute to elevated aromatase expression in inflamed breast tissue of obese women. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:356–65. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Subbaramaiah K, Howe LR, Bhardwaj P, Du B, Gravaghi C, Yantiss RK, et al. Obesity is associated with inflammation and elevated aromatase expression in the mouse mammary gland. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:329–46. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Duggan C, Irwin ML, Xiao L, Henderson KD, Smith AW, Baumgartner RN, et al. Associations of insulin resistance and adiponectin with mortality in women with breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:32–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, Peairs KS, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2754–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachelot T, Ray-Coquard I, Menetrier-Caux C, Rastkha M, Duc A, Blay JY. Prognostic value of serum levels of interleukin 6 and of serum and plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in hormone-refractory metastatic breast cancer patients. British journal of cancer. 2003;88:1721–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sicking I, Edlund K, Wesbuer E, Weyer V, Battista MJ, Lebrecht A, et al. Prognostic influence of pre-operative C-reactive protein in node-negative breast cancer patients. PloS one. 2014;9:e111306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allin KH, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Baseline C-reactive protein is associated with incident cancer and survival in patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2217–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Taylor SK, et al. Insulin- and obesity-related variables in early-stage breast cancer: correlations and time course of prognostic associations. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:164–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu XJ, Gauthier MS, Hess DT, Apovian CM, Cacicedo JM, Gokce N, et al. Insulin sensitive and resistant obesity in humans: AMPK activity, oxidative stress, and depot-specific changes in gene expression in adipose tissue. Journal of lipid research. 2012;53:792–801. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kloting N, Fasshauer M, Dietrich A, Kovacs P, Schon MR, Kern M, et al. Insulin-sensitive obesity. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;299:E506–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00586.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denis GV, Obin MS. ‘Metabolically healthy obesity’: origins and implications. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2013;34:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, Chen Y, Liu X, Li M, Wu B, Li Y, et al. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in normal-weight individuals. Endocrine. 2014;46:496–504. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deepa M, Papita M, Nazir A, Anjana RM, Ali MK, Narayan KM, et al. Lean people with dysglycemia have a worse metabolic profile than centrally obese people without dysglycemia. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2014;16:91–6. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arendt LM, McCready J, Keller PJ, Baker DD, Naber SP, Seewaldt V, et al. Obesity promotes breast cancer by CCL2-mediated macrophage recruitment and angiogenesis. Cancer research. 2013;73:6080–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grossmann ME, Nkhata KJ, Mizuno NK, Ray A, Cleary MP. Effects of adiponectin on breast cancer cell growth and signaling. British journal of cancer. 2008;98:370–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang CC, Wu MJ, Yang JY, Camarillo IG, Chang CJ. Leptin-STAT3-G9a Signaling Promotes Obesity-Mediated Breast Cancer Progression. Cancer research. 2015;75:2375–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 46.Nakayama S, Miyoshi Y, Ishihara H, Noguchi S. Growth-inhibitory effect of adiponectin via adiponectin receptor 1 on human breast cancer cells through inhibition of S-phase entry without inducing apoptosis. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;112:405–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D. The proliferating role of insulin and insulin-like growth factors in cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belardi V, Gallagher EJ, Novosyadlyy R, LeRoith D. Insulin and IGFs in obesity-related breast cancer. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2013;18:277–89. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novosyadlyy R, Lann DE, Vijayakumar A, Rowzee A, Lazzarino DA, Fierz Y, et al. Insulin-mediated acceleration of breast cancer development and progression in a nonobese model of type 2 diabetes. Cancer research. 2010;70:741–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodwin PJ, Parulekar WR, Gelmon KA, Shepherd LE, Ligibel JA, Hershman DL, et al. Effect of metformin vs placebo on weight and metabolic factors in NCIC CTG MA.32. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. White adipose tissue inflammation. A. CLS-B positive breast WAT. H&E (upper panel) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (lower panel); 40× (left panel) and 400× (right panel). Arrow indicates CLS-B. B. CLS-B negative breast WAT. H&E (upper panel) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (lower panel); 40× (left panel) and 400× (right panel). WAT, white adipose tissue; CLS-B, crown-like structures of the breast.