Abstract

ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP acting as ligands of specific P2Y receptors activate intracellular signaling cascades to regulate a variety of cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and cell death. Contrary to a widely held opinion, we show here that nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioate analogs, containing a sulfur atom in a place of one nonbridging oxygen atom in a phosphate group, act as ligands for selected P2Y subtypes. We pay particular attention to the unique activity of thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate (TMPS) which acts as a specific partial agonist of the P2Y6 receptor (P2Y6R). We also collected evidence for the involvement of the P2Y6 receptor in human epithelial adenocarcinoma cell line (HeLa) cell migration induced by thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate analog. The stimulatory effect of TMPS was abolished by siRNA-mediated P2Y6 knockdown and diisothiocyanate derivative MRS 2578, a selective antagonist of the P2Y6R. Our results indicate for the first time that increased stability of thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate as well as its affinity toward the P2Y6R may be responsible for some long-term effects mediated by this receptor.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11302-015-9492-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: P2Y receptors, P2Y6, Nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates, HeLa cells, Cell migration

Introduction

Purines and pyrimidines have widespread and specific extracellular signaling actions in the regulation of a variety of functions in many tissues acting as ligands of specific P2 receptors. The P2X family consists of seven subtypes (P2X1-7), all forming channels by assembly of subunits of the same (homo-oligomers) or different (hetero-oligomers) subtypes [1]. G-protein-coupled P2Y receptors (P2YRs) are subdivided into P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14 that have different binding affinities for each nucleotide. P2Y1, P2Y12, and P2Y13 are preferentially activated by ADP whereas P2Y6 is activated by UDP [2, 3]. The P2Y11 receptor prefers ATP as an agonist whereas P2Y2 responds to both ATP and UTP. UTP is the endogenous P2Y4 agonist while ATP antagonizes the human homolog of this receptor and activates the rat homolog [4, 5]. The P2Y14 receptor is activated by the nucleotide sugar conjugate (UDP-glucose) [6].

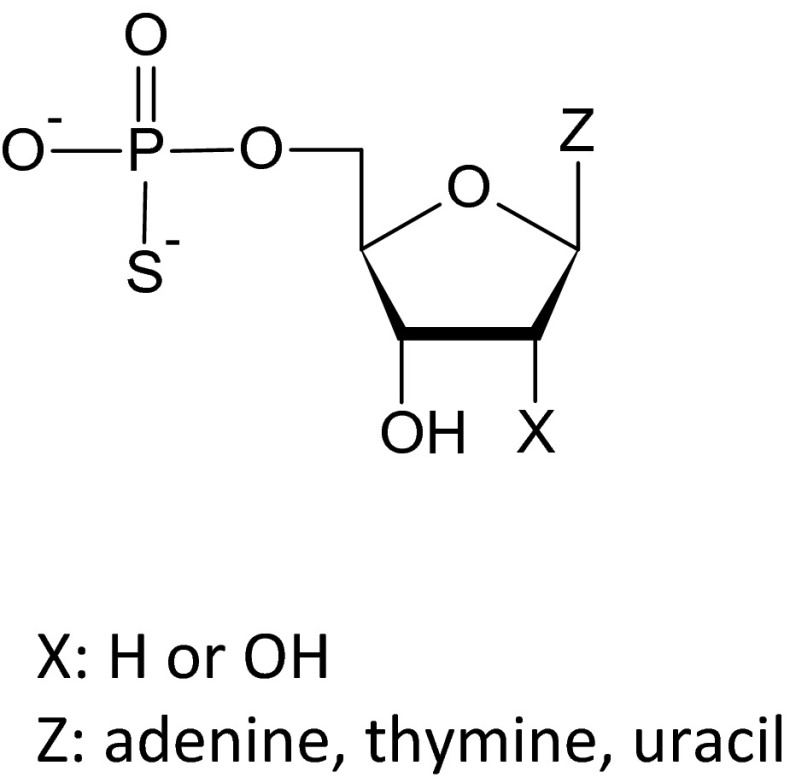

There is a growing interest in the long-term trophic influence of extracellular nucleotides on cell growth, proliferation, and death. Ligands of the P2YRs are of potential interest for pharmacotherapies directed at neurodegenerative disorders, intestinal function, angiogenesis, cardiac remodeling, etc. Naturally occurring nucleotides including ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP induce P2Y-mediated mitogenic effects in endothelial cells [7, 8], vascular smooth muscle cells [9, 10], fibroblasts [11, 12], glial and neuronal cells [13], epithelial cell lines [14], as well as HeLa human cervix carcinoma cells [15]. In our previous studies, we have shown that phosphorothioate analogs of deoxyribonucleoside 5′-O-monophosphates and ribonucleoside 5′-O-monophosphates (Fig. 1), containing a sulfur atom in a place of one nonbridging oxygen atom in a phosphate group, not only demonstrated significant resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis but also induced an increased viability of HUVEC and leukemia HL-60 cells. The highest proliferative effect was caused by thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate (TMPS). According to our findings, the influence of extracellular nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs depended on the activity of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase present at the cell surface. However, ectonucleotidase activity did not seem to be the only mechanism responsible for the biological activity of these compounds [16].

Fig. 1.

Structures of nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioate analogs studied

This study was initiated to identify the P2Y receptor subtype involved in TMPS-induced signaling. We tested a series of pyrimidine nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs and revealed that besides stimulation of cellular viability, pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates are able to potentiate migratory potency of the cervical epithelial carcinoma HeLa cells, representing the “work horse” of many cell biology laboratories. Since it was shown that UDP induced intestinal epithelial migration via the P2Y6 receptor [17], we aimed to investigate the possible modulation of the P2Y6 receptor by pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates as well. We adopted in vitro scratch wound assay linked to specific inhibition of P2Y6 gene expression by small interfering RNAs and diisothiocyanate derivative MRS 2578, which is a selective antagonist of the P2Y6R. Agonist activities of thymidine and uridine 5′-monophosphorothioates were confirmed in 1321N1 cells expressing the human P2Y6 receptor.

Materials and methods

Tested compounds

Nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs were purchased from the following sources: UDP, UTP, and UMP from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA) and UDPβS, TMPS, UMPS, and AMPS from BioLog (Bremen, Germany). The P2Y6 receptor-selective antagonist MRS 2578 [18] was provided by Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in DMSO (5 mM).

HeLa cell culture

The cervical epithelial carcinoma HeLa cell line was purchased from the American Type Cell Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All reagents for cell culture were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95 % air and 5 % CO2.

Cell viability assay

HeLa cells were seeded into 96-well plates in the number of 5 × 103 per well in complete medium. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were starved for another 24 h in the culture medium without serum. Subsequently, the fasting medium in each well was supplemented with a respective nucleotide added to a final concentration of 100 μM. HeLa cells were incubated in the presence of investigated compounds for either 24 or 48 h. Following incubation, 10 μl of PrestoBlue cell viability reagent (Life Technologies, Van Allen Way, CA, USA), a resazurin-based solution, was added into each well and incubated further for 80 min at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. Cell viability was determined by measuring the fluorescent signal F530/590 on a Synergy 2 Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The obtained fluorescence magnitudes were used to calculate cell viability expressed as a percent of the viability of the untreated control cells.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cell culture using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands) and purified with Amplification Grade DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). RNA samples were reverse-transcribed with RT2 First Strand Kit (SABioscences, Frederick, MD, USA). Primers were designed using the NCBI’s Primer-BLAST software (National Center for Biotechnology Information) based on receptors’ sequences from the GenBank database and purchased from Genomed (Warsaw, Poland). The sequences of specific primers were as follows: P2Y6 5′-ATGCCTGCTCCCTGCCCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCGAAGTCGCCAAAGGGCC-3′ (reverse) (NM 176798); GAPDH 5′-AAGGCTGGGGCTCATTTGCAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCAGGGGTGCTAAGCAGTTGG-3′ (reverse) (NM 002046). Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using SYBR® Green-based RT2 qPCR Master Mix (SABioscences) on a CFX96™ detection system (C1000 Touch, Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Complementary DNA representing 6 ng per sample of total RNA was subjected to 40 cycles of PCR amplification. Samples were first incubated at 95 °C for 15 s, then at 60 °C for 30 s, and finally at 72 °C for 30 s. To exclude nonspecific products and primer dimers, after the cycling protocol, a melting curve analysis was performed by maintaining the temperature at 55 °C for 2 s, followed by a gradual increase in temperature to 95 °C. The PCR products were electrophoretically separated on a 2.5 % agarose gel in Tris/acetate/EDTA containing adequate volume of nucleic acid stain (Midori Green Advance DNA stain, NIPPON Genetics, Japan). Constitutively expressed GAPDH gene was selected as an endogenous control to correct potential variation in RNA loading. Expression of the P2Y6 nucleotide receptor was normalized to GAPDH for giving relative expression values. The amount of target gene expression level was calculated as 2 − ΔCt, where ΔCt = [Ct(target) − Ct(GAPDH)].

siRNA transfection

HeLa cells were seeded into 24-well plates in the number of 4 × 104 per well to achieve a confluency of 70–80 % on the day of transfection. After 24 h of incubation, the complete medium was exchanged into complete one but without antibiotics. The P2Y6 siRNA or nontargeting siRNA (Dharmacon, Sweden) at a final concentration of 125 nM was incubated with DharmaFECT tranfection reagent (Thermo Scientific, USA) in RPMI 1640 at room temperature for 20 min to form complexes, and then added to the cells. Forty-eight hours later, RNA was isolated and the efficacy of transfection was confirmed by RT-qPCR and electrophoresis.

Scratch wound migration studies after siRNA-mediated knockdown

At 48 h posttransfection, HeLa cells were washed with PBS and stayed starved for another 24 h in the RPMI 1640 medium without serum. Subsequently, a straight scratch line was made on cells monolayer with a 200-μL pipette tip. Cells were washed with PBS and further cultured in RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of tested nucleotides added to a final concentration of 100 μM. Wound closure was measured and recorded immediately, 24 and 48 h after wounding at the same spot with an inverted microscope equipped with a digital camera (Nikon, Eclipse TS100) and then compared to the initial gap size at 0 h. The extent of healing was defined as the ratio of the difference between the original and the remaining wound areas compared with the original wound area and calculated according to the following formula: Percent increase in migration [%] = 100 × [(area of stimulated sample at the beginning − area of stimulated sample after incubation) − (area at the beginning in control − area after incubation in control)] / (area at the beginning in control − area after incubation in control).

Scratch wound migration studies after pretreatment with MRS 2578

HeLa cells were seeded into 24-well plates in the number of 4 × 104 per well in complete medium. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were starved for another 24 h in the culture medium without serum. Subsequently, a straight scratch line was made on cell monolayer with a 200-μL pipette tip and MRS 2578 (37 nM) was added 60 min prior to the addition of tested nucleotides (100 μM). Wound closure was measured as described above.

Calcium mobilization assay in mammalian cells stably expressing individual P2Y receptors

Cell-based assays for activation of P2Y receptors were performed by GenScript Corporation (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and Multispan Inc. (Hayward, CA, USA). Briefly, in the case of GenScript Co., 1321N1 cells expressing human P2Y1–P2Y12 receptors were seeded in a 384-well black-wall, clear-bottom plate at a density of 20,000 cells per well in 20 μL of growth medium,18 h prior to the time of experiment. Then, dye-loading solution (FLIPR® Calcium 4 assay kit, Molecular Devices Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was added into the well and the plate was placed in a 37 °C incubator for 60 min, followed by 15-min stay at room temperature. TMPS or control agonists were added to the reading plate 20 s after starting the measurement, and the fluorescence signal was monitored for additional 100 s (from 21 to 120 s). In the case of Multispan Inc., 1321N1 cells expressing human P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y13, and HEK293T cells with stable expression of P2Y14, the cells were seeded in 384-well black-wall, clear-bottom plates. Ca2+ flux assays were conducted after overnight culture according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Screen Quest™ Fluo-8 No Wash kit (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Dye loading buffer was added to the cells and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Calcium flux was monitored for 90 s after compound’s application. The relative fluorescent unit intensity values (ΔRFU) were calculated from maximal fluorescence reading after subtracting the average value of baseline reading.

The percentage of activation by a given compound was calculated from the following equation:

Chromatographic analysis of extracellular catabolism of nucleotides

HeLa cells were incubated with nucleotides (200 μM) for 72 h in RPMI 1640 culture medium containing 10 % FBS. At given time points, 250 μL aliquots were removed from the cell cultures, denatured for 30 min at 95 °C, and spun down. The samples were maintained at −20 °C prior to HPLC analysis. The incubation mixtures were analyzed by means of reverse-phase HPLC on elution with 0.1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) and CH3CN gradient: from 0 to 12 % CH3CN for 35 min; then from 12 to 40 % CH3CN for 3 min; and finally from 40 to 0 % CH3CN for 2 min (altogether 40 min). Under these conditions, products of the enzymatic degradation of nucleotides and corresponding nucleosides have been readily separated. In control experiments, 5′-O-mononucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs were incubated in 10 % FBS-supplemented medium or in the cell culture medium from which cells were removed after 72-h incubation. These experiments have been carried out to show that ecto-5′-NT activity responsible for mononucleotide dephosphorylation is cell-associated and that this activity is neither present in serum nor released from cells into medium.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in a minimum of triplicate. All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Assays involving treatment with a single compound were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Assays using more than one drug were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. Statistical significance was determined P value less than 0.05. Differences between groups were rated significant at a probability error P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***), and P < 0.0001 (****).

Results

The effect of extracellular nucleotides on HeLa viability

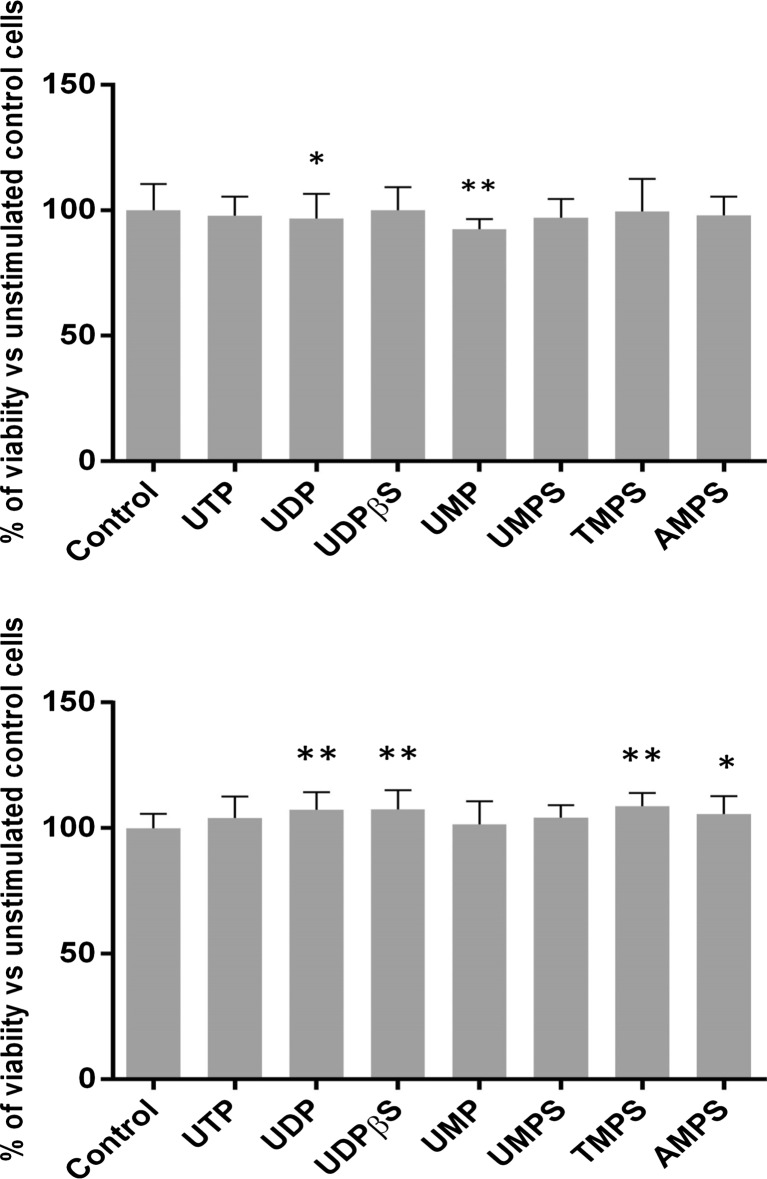

We first examined the effects of a series of pyrimidine nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs on HeLa cell growth using a rezasurin-based PrestoBlue cell viability reagent. We compared the effect of the natural uridylic family UTP, UDP, and UMP. Since UTP can be catabolized by ectonucleotidases into UDP and UDP can be converted into UTP by extracellular ectonucleotide diphosphokinase [19], we also employed nondegradable uridine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) (UDPβS) that previously was shown to be a specific agonist for P2Y6 receptor [20]. Additionally, we utilized pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates (UMPS, TMPS) serving as prime subjects of this research. Finally, we also tested adenosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate (AMPS) as a purine nucleotide control. The results showed that in most cases, neither cytotoxic nor stimulating effect of nucleotides used at a concentration of 100 μM was observed. After 24 h of incubation, only unmodified uridine monophosphate decreased the number of viable cells, while after 48 h, UDP, UDPβS, TMPS, UMPS, and AMPS slightly induced cell growth (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The effect of nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs on the viability of HeLa cells. Viability was assessed using PrestoBlue kit for 100 μM concentrations of tested compounds after 24 h (a) and 48 h (b) of incubation. Data represent the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus unstimulated control cells (100 %); n = 6

The effect of extracellular nucleotides on HeLa migration

Our data indicated that pyrimidine nucleotides had no obvious effect on the HeLa viability. Thus, we further examined if tested compounds regulated the migratory potency of these cells with scratch wound migration assay. Recent data suggest that UDP plays a key role in promoting the migration of intestinal epithelium via activation of P2Y6 receptors [17]. Although the reported expression patterns of P2Y receptors in HeLa cells vary among the different studies, the presence of P2Y6 mRNA has consistently been confirmed. Namely, Muscella et al. showed that HeLa cells express mRNAs for both P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors, however not for P2Y1, P2Y4, and P2Y11 [15]. Moore et al. detected the presence of P2Y6 and P2Y11, but not P2Y2 mRNA [21], while Okuda et al. showed that HeLa cells express P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 mRNA [22]. More recently, Welter-Stahl et al. found the products of the size expected for P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14mRNA among the products of PCR amplification of HeLa mRNA [23].

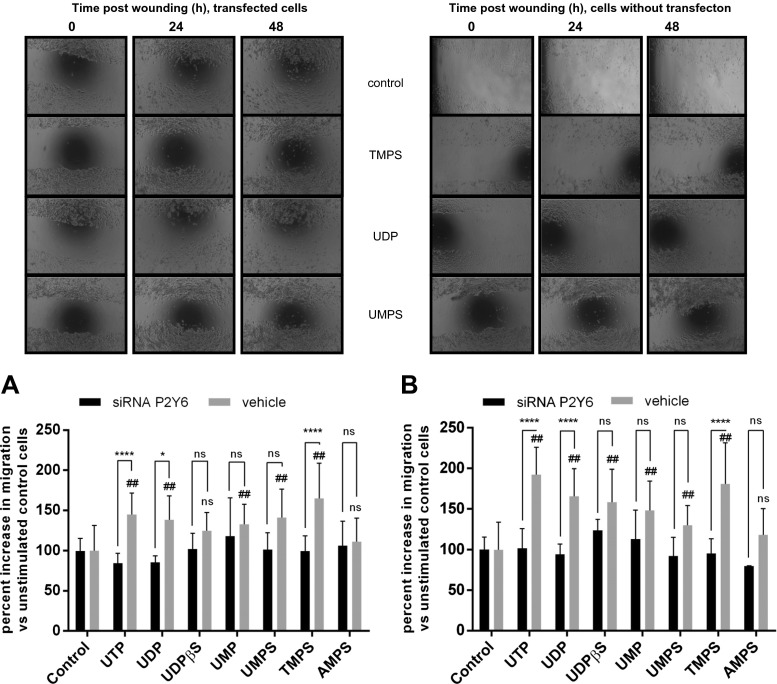

Among the nucleotides exogenously applied to the cells in our studies (UDP, UTP, UMP, UDPβS, TMPS, UMPS) at a concentration of 100 μM, only AMPS did not enhance HeLa cell migration significantly. Interestingly, all pyrimidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioates tested accelerated cell migration at a similar degree to UDP and UDPβS at 24 h. At 48 h, TMPS enhanced the migration more effectively than UMPS (Figs. 3b and 4b). At least three receptors, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6, are known to respond to pyrimidine nucleotides and could mediate the HeLa migration induced by pyrimidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioates. Among those three receptors, activation of P2Y6 seemed be the most probable because UDPβS was previously shown to be a specific agonist for P2Y6 receptors with no effect on P2Y2 and P2Y4 [20]. Besides, it was shown that UDP induced intestinal epithelial migration via the P2Y6 receptor [17]. Thus, we examined next whether the enhancement of HeLa migration by TMPS and UMPS was specifically mediated via the P2Y6 receptor using knockdown by siRNA. P2Y6 siRNA as well as nontargeting siRNA were transfected into HeLa cells. Using RT-qPCR, we first showed that P2Y6 siRNA but not vehicle siRNA significantly reduced the P2Y6 mRNA amount in HeLa cells (Supplementary materials). The P2Y6 siRNA treatment significantly diminished the maximum effect of UDP and TMPS as compared with vehicle control (Fig. 3a, b). The stimulatory effect of UTP was also abolished by P2Y6 siRNA, suggesting that this effect depends on its conversion into UDP and activation of P2Y6 receptors. Treatment of HeLa cells with UDPβS and UMPS after P2Y6 siRNA transfection was also diminished but not enough to achieve statistical significance. In the case of those two nucleotides, P2Y6R might be not the only receptor target involved in induced migration.

Fig. 3.

The effect of nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs on the migration of control HeLa cells and cells with P2Y6 knockdown (siRNA). After creating a scratch, tested nucleotides were added to a final concentration of 100 μM. Area of wound was measured after 24 h (a) and 48 h (b), and the extent of healing was calculated as the percent increase of cellular migration. Data represent the means ± SD; *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 when compared to siRNA transfected cells; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 when compared to unstimulated control cells (100 %); NS nonsignificant when compared to control cells; n = 5

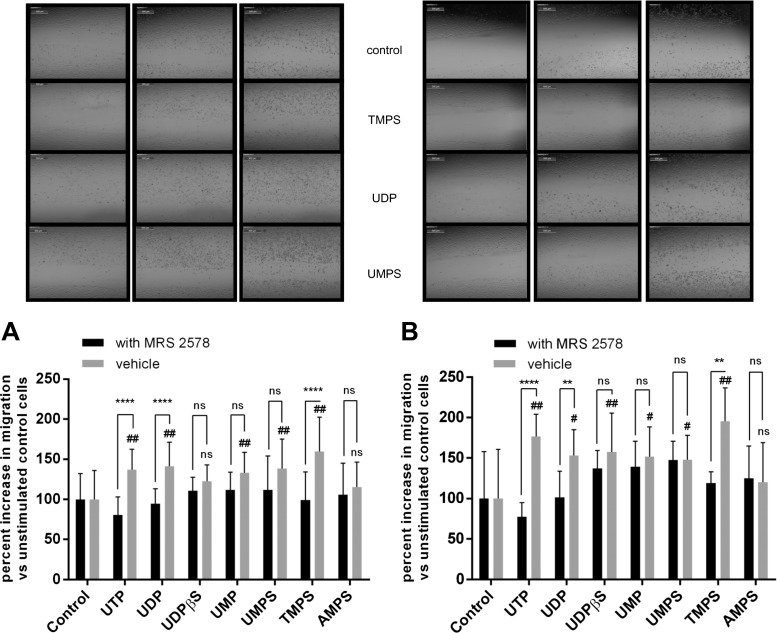

Fig. 4.

The effect of nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs on the migration of control HeLa cells and cells treated with MRS 2578. After creating a scratch, MRS 2578 (37 nM) was added 60 min prior to the addition of tested nucleotides (100 μM). Area of wound was measured after 24 h (a) and 48 h (b), and the extent of healing was calculated as the percent increase of cellular migration. Data represent the means ± SD; *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 when compared to MRS 2578-treated cells; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 when compared to unstimulated control cells (100 %); NS nonsignificant when compared to control cells; n = 5

To examine the role of P2Y6 receptors, we also used MRS 2578 (N,N″-1,4-butanediylbis[N′-(3-isothiocyanatophenyl)thiourea), a potent P2Y6 antagonist with IC50 values of 37 and 98 nM at human and rat P2Y6 receptors, respectively [18]. One-hour preincubation with MRS 2578 blocked UDP-, UTP-, and TMPS-mediated migratory responses of HeLa cells (Fig. 4a, b). Similarly to siRNA-mediated P2Y6 knockdown, MRS 2578 did not block UDPβS- and UMPS-mediated migration. The lack of significant inhibition in the case of UDPβS that was previously demonstrated as a specific agonist for P2Y6 receptor [20] may result from activation of additional P2Y receptors. Indeed, UDPβS (EC50 = 26 ± 11 nM) was also potent agonists at the P2Y14R [24]. The results clearly suggest that thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate plays a key role in promoting the migration of HeLa cells via activation of the P2Y6 receptor.

Calcium mobilization assay in mammalian cells stably expressing individual P2Y receptors

To confirm unambiguously the activation of the P2Y6 by pyrimidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioates, we decided to test an agonist activity of the most active inducer of HeLa cell migration, namely TMPS, using mammalian cells expressing human individual P2Y receptors (P2Y1–P2Y14). Cells were probed with thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate in a dose-dependent manner ranging from 1.0 to 1000 μM. We found that TMPS behaved as an agonist of the human P2Y6 receptor but it did not show stimulatory activity on the other P2Y receptor tested even at the highest concentration tested (Supplementary material Table 1). Thus, introduction of a thio modification in a phosphate group of TMP afforded TMPS with enhanced selectivity toward P2Y6R versus other P2Y receptors. At a concentration of 1 mM, TMPS displayed significant P2Y6R agonist activity with a maximal response corresponding to 49.8 ± 9.3 % of the response induced by UDP at 1.0 μM. According to those data, we then compared agonist activities of UMPS, AMPS, and UMP at the P2Y6 receptor. UMPS appeared to be even more potent than TMPS showing dose-dependent agonist activity (Table 1). For example, at a concentration of 10 μM, the effect of UMPS represented 61.9 ± 17.4 % of the maximal UDP response used at a concentration of 1.0 μM. However, uridine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate, unlike TMPS, also elicited a calcium response in HEK293T cells with stable expression of P2Y14R. It was event more potent as a P2Y14 agonist because at a concentration of 10 μM, the response corresponded to 80.7 ± 12.9 % of the maximal UDP-glucose response used at a concentration of 10.0 μM. The lack of UMPS specificity is similar to UDP that was reported to activate not only P2Y6R but also P2Y14R [24]. For comparison, UMP that was reported previously to be inactive against P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors [25, 26] did not show any activity in our studies. Similarly, AMPS appeared to be inactive as a P2Y6 agonist confirming our hypothesis on the involvement of the P2Y6 receptor in the pyrimidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioates-mediated signaling leading to HeLa cell migration.

Table 1.

Nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates-dependent intracellular calcium response in 1321N1 cells expressing human P2Y6 receptor (% activation as compared to the control agonist UDP used at a concentration of 1.0 μM)

| Nucleotide | Concentration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 μM | 100 μM | 10 μM | 1 μM | |

| TMPS | 49.8 ± 9.3* | 11.0 ± 2.7* | 2.2 ± 0.3 | NE |

| UMPS | 102.7 ± 0.2* | 93.0 ± 1.9* | 61.9 ± 17.4* | 7.8 ± 0.5* |

| UMP | 5.3 ± 0.4 | NE | NE | NE |

| AMPS | 5.5 ± 0.5 | NE | NE | NE |

Calcium mobilization assay in 1321N1 cells expressing human P2Y6 receptor was performed by Multispan Inc. (details in “Materials and methods”). Data represent the average ± SD of at least triplicate determinations

NE no effect

*P < 0.05 test

Chromatographic analysis of extracellular catabolism of nucleotides

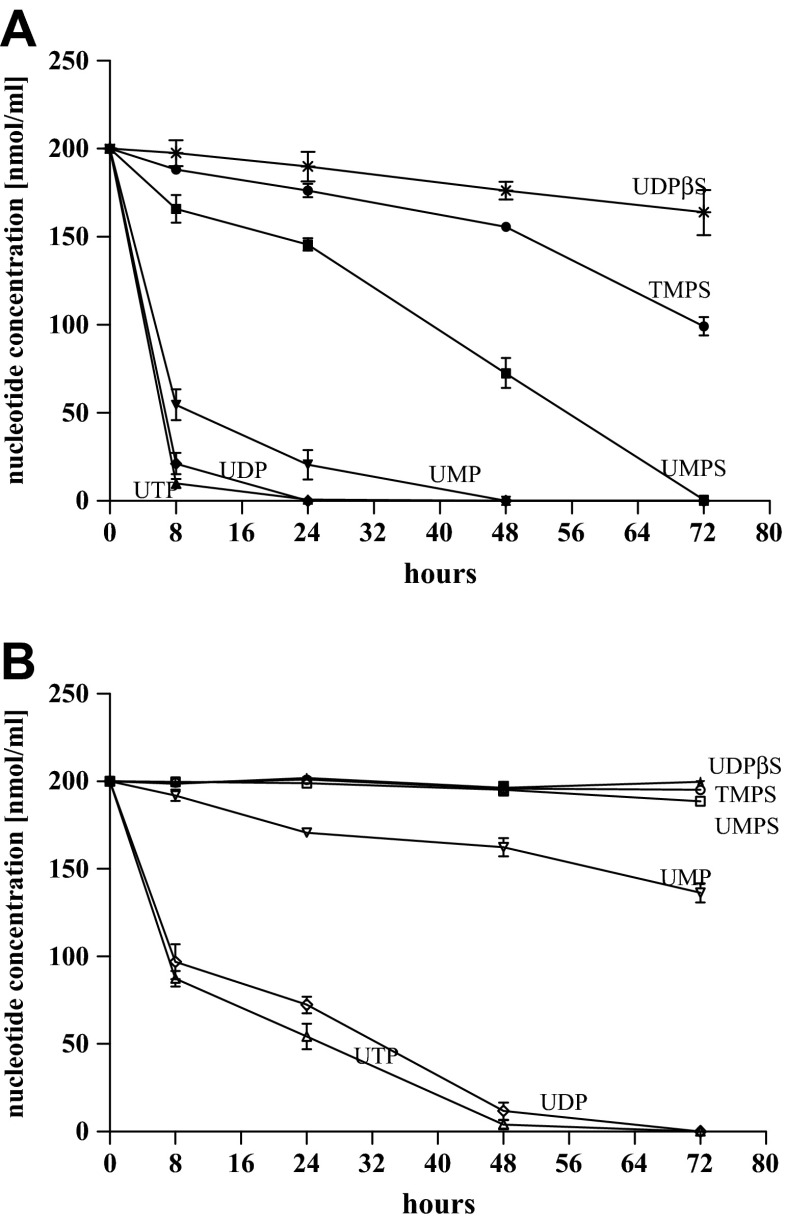

In the present studies, we also performed HPLC analysis to compare the stability of uridine monophosphates, diphosphates, and triphosphates, as well as UMPS, TMPS, and UDPβS in HeLa cell cultures. HeLa cells growing in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS were incubated with those compounds for 72 h, and the resultant media supernatants were analyzed by HPLC. This analysis revealed that UDP, UTP, and UMP were almost completely dephosphorylated to the corresponding nucleosides during a 8-h incubation time (Fig. 5a). Among the nucleotides studied, only uridine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) was not hydrolyzed in HeLa cells during 72 h, confirming that nucleoside 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphates) are resistant to nucleotide pyrophosphatase and NTPdiphosphohydrolases family due to aforementioned preferences of nucleotide pyrophosphatase to the α and γ phosphorus atoms [27].

Fig. 5.

Time course of degradation of extracellular nucleotides and their phosphorothioate analogs in HeLa cell culture (a) or in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS (b). The catabolism was determined by reversed phase HPLC of subsamples taken at 0, 4, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h after addition of the studied nucleotides (200 μM). The ordinate axis shows the concentration of unchanged substrate. Data points represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments, n = 3

We previously demonstrated that TMPS was more effectively dephosphorylated by the ecto-5′-nucleotidase (ecto-5′-NT) from HeLa cells than deoxyadenosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate and deoxyguanosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate [16]. Here, we show that under the same conditions ecto-5′-NT from HeLa cells dephosphorylated UMPS completely (Fig. 5a). It is the first observation that ecto-5′-nucleotidase is able to recognize and hydrolyze also uridine-5′-monophosphorothioates. Among nucleoside-5′-phosphorothioates UMPS seems to be a substrate better than TMPS. Analysis of the control samples revealed that after a 72-h incubation, approximately only 30 % of UMP was converted to the corresponding nucleosides by serum enzymes in RPMI medium containing 10 % FBS. Its 5′-phosphorothioate analog appeared completely stable (Fig. 5b). Thus, degradation of nucleotides and their analogs is mainly connected with the presence of cellular enzymes.

Discussion

The P2Y6 receptor is widely distributed in the human body and ligands of P2Y6R are of potential interest for pharmacotherapies. Activation of P2Y6R by its native ligand UDP or by synthetic agonists is associated with vasoconstriction and cytoprotection. Cytoprotective role of the P2Y6 receptor was demonstrated by its implication in protection against apoptosis induced by the tumor necrosis factor α in astrocytes and skeletal muscle [28], protection against skeletal muscle ischemia/reperfusion injury in in vivo mouse hindlimb model [29], and the enhancement of osteoclast survival through NF-κB activation [30]. P2Y6-mediated phagocytosis in microglial cells was also discovered, suggesting the possible application of P2Y6R ligands for the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions [31]. P2Y6R seems to control chloride secretion by epithelium [32], the direct contraction and endothelium-dependent relaxation of the aorta [33], and insulin secretion [34] as well. UDP applied topically to the rabbit cornea reduced intraocular pressure, suggesting the use of P2Y6 receptor agonists for the treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma [35]. Finally, P2Y6R could be a novel mediator in upregulating innate immune response against the invaded pathogens through recruiting monocytes/macrophages [36]. Pharmacological modulation of the P2Y6 receptor is of increasing interest; nevertheless, UDP as a natural ligand was reported to activate not only P2Y6R but also P2Y14R. Therefore, agonists that delineate between these two subtypes are needed [24].

In comparison with ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP, nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphates are thought to have no agonist activity for the nucleotide receptors. UMP has been reported to be inactive against P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors, similarly to AMP being inactive against ATP- or ADP-activated P2 receptor subtypes [25, 26]. However, substitution of a 2-keto group in UMP by NH (iso-CMP) resulted in the potent and selective P2Y4 agonist, >20-fold selective vs P2Y2 and P2Y6 [37] whereas introducing a bromine atom into 5 position of UMP enhanced its potency toward P2Y6 [38]. AMP derivatives, e.g., 2-hexylthio-AMP, 2-hexynyl-AMP, or 2-phenylethynyl-AMP, were reported to act as P2Y agonist/antagonists [39, 40]. Finally, derivatization of a phosphate group in adenosine-5′-O-phosphorothioate was shown to create a partial agonist of P2Y11 receptor. At a concentration of 300 μM, the effect of AMPS represented 63 ± 16 % of the ATP response [41]. AMPS was also found to inhibit ATP-induced cyclic AMP production in undifferentiated human promyelocytic HL60 cells [42].

The P2Y6 receptor is highly selective for 5′-diphosphate derivatives. Thus, UMP, 2′-deoxyuridine 3′,5′-bisphosphate, a cyclic 3′,5′-diphosphate analog, and a uridine 3′-diphosphate derivative are inactive as either agonists or antagonists [43]. Among phosphorothioate analogs of pyrimidine nucleotides, only UDPβS was found to be a potent agonist of P2Y6 receptor. UDPβS and UDP stimulated [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation in P2Y6 receptor-expressing 1321N1 cells to similar maximal levels and with similar EC50 values [EC50 = 28 ± 13 nM for UDPβS; EC50 = 47 ± 15 nM for UDP] [20]. In other studies, UDPβS (EC50 = 47 nM) was even more potent than UDP (EC50 = 300 nM) [43]. Our results show that pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates can also act as P2Y6 agonists, albeit less potent than uridine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) in the capacity to activate the human recombinant P2Y6R stably expressed in 1321 N1 cells. Although TMPS and UMPS are weaker agonists than UDPβS, their P2Y6-mediated stimulation of HeLa cell migration is comparable with the effect generated by UDPβS. Our results indicate that increased stability of UMPS and TMPS as well as their affinity toward the P2Y6 receptor may be responsible for some long-term effects mediated by this receptor. Interestingly, the P2Y6 receptor appeared to be the only one responsive to thymidine 5′-monophosphorothioate among the P2Y family and TMPS acted as its partial agonist. Uridine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate appeared to be more potent; however, we also observed activation of P2Y14R suggesting the lack of specificity in the case of UMPS. Unmodified UMP nucleotide remained inactive similar to adenosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate. These results indicate that a phosphorothioate group of pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates plays a crucial role in activation of P2Y6 receptor. One can suppose that this effect results not only from greater resistance of phosphorothioate 46tested but also from properties of sulfur atom and the binding pocket of the P2Y6 receptor.

Recently, the structure-activity relationship of P2Y6 agonists and antagonists has been extensively investigated [38, 44–47]. Constanzi et al. proposed that nucleotides bind to the P2Y6 receptor with the sugar moiety accommodated between TM3 and TM7, with the base pointing toward TM1 and TM2 and with the polyphosphate moiety pointing in the direction of TM6. According to this model, the phosphate moiety of UDP bound to the positively charged subpocket formed by three cationic amino acids from TM3, TM6, and TM7, namely R103(3.29), K259(6.55), and R287(7.39) [45]. Further modeling data suggested that the β-phosphate of UDP and related analogs is fundamental for the establishment of electrostatic interactions with two of the three cationic residues, namely, K259(6.55) and R287(7.39). Thus, UMP, which lack a β-phosphate linked through the 5′ position of ribose, was inactive at the P2Y6 receptor.

On the other hand, it is well known that the replacement of one of the two nonbridging oxygen atoms at the phosphate group by a sulfur atom introduces P-S bond (which is 0.5 Å longer than the corresponding P-O linkage) and changes charge distribution with localization of the negative charge on sulfur atom [48]. Consequently, the remaining oxygen atom is less negative and the P=O bond is shorter than that one in unmodified phosphate. These changes can influence metal ion binding and/or hydrogen bonding. Detailed analysis of complexes formed by divalent metal ions with uridine 5′-monophosphorothioate indicated that the sulfur of the phosphorothioate residue participated in the binding of zinc cations and the resulting complex is more stable than that one formed by unmodified uridine monophosphate [49]. In other words, the “soft” Zn2+ ion binds preferentially the soft sulfur atom rather than the “hard” oxygen atom. The zinc atom of the complex can also be coordinated by some amino acid residue(s) of the receptor binding pocket. According to suggestions of Major et al. [50], in the case of P2Y1 receptor and ATP ligand, Asp 204 residue from EL2 can coordinates Mg2+ ion bound to polyphosphate chain of ATP, and can indirectly bind the nucleotide molecule. However, to the best of our knowledge, no experiments have been done to identify a metal ion involved in the binding of P2Y ligands and, in our opinion, the participation of Zn2+ ion in the binding of phosphorothioate analogs of the P2Y ligands cannot be excluded. Aspartate D179 from EL2 of the P2Y6 binding pocket corresponds to the Asp 204 of the P2Y1 and probably has the same function. Molecular modeling of human P2Y6R carried out by Costanzi et al. indicates that the electrostatic interaction of the phosphate moiety with three cationic residues from TM3, TM6, and TM7 (3.29, 6.55, and 7.39) is fundamental for the recognition of nucleotides. However, aspartate D179 (EL2) seems to be repelled toward the extracellular space by the negative charge of the ligand [44]. In the case of the phosphorothioate analog of UDP, metal ion (possibly zinc) results in partial neutralization of the ligand negative charges and its proper alignment in the binding pocket of the receptor. Due to these effects, phosphorothioate analogs of uridine nucleotide could be bound by Asp 179 more tightly than the unmodified ligands. Indeed, UDPβS (EC50 = 47 nM) was found to be 6-fold more potent than UDP in activation of the P2Y6 (EC50 = 300 nM) in activation of the P2Y6 receptor [44]. Summarizing, higher affinity of phosphorothioate analogs of pyrimidine nucleotides to the P2Y6 receptor may be caused the presence of negatively charged, metal-ion-binding phosphorothioate group. Above arguments suggest an explanation of higher activity of UMPS in stimulation of HeLa cell migration than that observed for UMP. On the other hand, it was also revealed, that the 2′-OH group, although important in the stabilization of the ligand through an intramolecular H-bond with the 2-O, was not involved in crucial interactions with the receptor. Thus, 2′-deoxyUDP, although less potent than UDP, it maintained full agonistic activity at the P2Y6 receptor [46], and thus, TMPS may also act as P2Y6 agonist although with lower potency than UMPS.

In conclusion, our studies reveal that pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates can act as agonists of the P2Y6 receptor. We pay particular attention to the unique activity of thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate (TMPS) which acts as a specific partial agonist of the P2Y6R. The increased stability of UMPS and TMPS as compared to their unmodified counterparts as well as their affinity toward P2Y6R may be responsible for some long-term effects. UMPS is degraded by ecto-5′-NT more efficiently than TMPS on one hand, but on the other hand, it is a better P2Y6 agonist. In some circumstances, these properties could be very advantageous, especially for the induction of such long-term effects as cell proliferation, apoptosis, or cardioprotection. Very recently we have shown that nucleoside 5′-O-phosphorothioate analogs could serve as potential therapeutic agents for promoting impaired angiogenesis under diabetic conditions [51]. In the case of UMPS and TMPS, they could serve as P2Y6R agonists expected to be useful for the treatment of diseases such as neurodegeneration, diabetes or ocular hypertension, and glaucoma [30, 33, 34]. Biological activity of nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates should be also taken into consideration as yet sequence-specific effects RNA-based therapeutic technologies exploiting various oligonucleotides (e.g., RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides) [52].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PPTX 124 kb)

(DOC 34 kb)

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Project No. N 405 3047 36).

Abbreviations

- AMPS

Adenosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- MRS 2578

N,N″-1,4-butanediylbis[N′-(3-isothiocyanatophenyl)thiourea

- P2YR

P2Y receptor

- TMPS

Thymidine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate

- UDPβS

Uridine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate)

- UMPS

Uridine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Browne LE, Jiang LH, North RA. New structure enlivens interest in P2X receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Communi D, Parmentier M, Boeynaems JM. Cloning, functional expression and tissue distribution of the human P2Y6 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:303–308. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy C, Qi AD, Herold CL, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. ATP, an agonist at the rat P2Y4 receptor, is an antagonist at the human P2Y4 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:926–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbracchio MP, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Miras-Portugal MT, King BF, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA, Burnstock G. Characterization of the UDP-glucose receptor (re-named here the P2Y14 receptor) adds diversity to the P2Y receptor family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:52–55. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha SH, Hahn TW, Sekine T, Lee KH, Endou H. Purinoceptor-mediated calcium mobilization and cellular proliferation in cultured bovine corneal endothelial cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2000;82:181–187. doi: 10.1254/jjp.82.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satterwhite CM, Farrelly AM, Bradley ME. Chemotactic, mitogenic, and angiogenic actions of UTP on vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1091–H1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erlinge D. Extracellular ATP: a growth factor for vascular smooth muscle cells. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;31:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(97)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eun SY, Ko YS, Park SW, Chang KC, Kim HJ. IL-1β enhances vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via P2Y2 receptor-mediated RAGE expression and HMGB1 release. Vasc Pharmacol. 2015;72:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang N, Wang DJ, Heppel LA. Extracellular ATP is a mitogen for 3T3, 3T6, and A431 cells and acts synergistically with other growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7904–7908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin H, Seo J, Eun SY, Joo YN, Park SW, Lee JH, Chang KC, Kim HJ. P2Y2 R activation by nucleotides promotes skin wound-healing process. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:480–485. doi: 10.1111/exd.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neary JT, Rathbone MP, Cattabeni F, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Trophic actions of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides on glial and neuronal cells. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer R, Sedehizade F, Welte T, Reiser G. ATP- and UTP- activated P2Y receptors differently regulate proliferation of human lung epithelial tumor cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L376–L385. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00447.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muscella A, Elia MG, Greco S, Storelli C, Marsigliante S. Activation of P2Y2 purinoceptor inhibits the activity of the Na+/K + −ATPase in HeLa cells. Cell Signal. 2003;15:115–121. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koziolkiewicz M, Gendaszewska E, Maszewska M, Stein CA, Stec WJ. The mononucleotide-dependent, nonantisense mechanism of action of phosphodiester and phosphorothioate oligonucleotides depends upon the activity of an ecto-5′-nucleotidase. Blood. 2001;98:995–1002. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.4.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura T, Murata T, Hori M, Ozaki H. UDP induces intestinal epithelial migration via the P2Y6 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:883–892. doi: 10.1111/bph.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mamedova LK, Joshi BV, Gao ZG, von Kugelgen I, Jacobson KA. Diisothiocyanate derivatives as potent, insurmountable antagonists of P2Y6 nucleotide receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarowski ER, Homolya L, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Identification of an ecto-nucleoside diphosphokinase and its contribution to interconversion of P2 receptor agonists. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20402–20407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou M, Harden TK, Kuhn CM, Baldetorp B, Lazarowski E, Pendergast W, Moller S, Edvinsson L. UDP acts as a growth factor for vascular smooth muscle cells by activation of P2Y6 receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H784–H792. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00997.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DJ, Chambers JK, Wahlin JP, Tan KB, Moore GB, Jenkins O, Emson PC, Murdock PR. Expression pattern of human P2Y receptor subtypes: a quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;152:107–119. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda A, Furuya K, Kiyohara T. ATP-induced calcium oscillations and change of P2Y subtypes with culture conditions in HeLa cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2003;21:61–68. doi: 10.1002/cbf.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welter-Stahl L, da Silva CM, Schachter J, Persechini PM, Souza HS, Ojcius DM, Coutinho-Silva R. Expression of purinergic receptors and modulation of P2X7 function by the inflammatory cytokine IFNgamma in human epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter RL, Fricks IP, Barrett MO, Burianek LE, Zhou Y, Ko H, Das A, Jacobson KA, Lazarowski ER, Harden TK. Quantification of Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity reveals that UDP is a potent agonist of the human P2Y14 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:1341–1348. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guile SD, Ince F, Ingall AH, Kindon ND, Meghani P, Mortimore MP. The medicinal chemistry of the P2 receptor family. Prog Med Chem. 2001;38:115–187. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller CE. P2-pyrimidinergic receptors and their ligands. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:2353–2369. doi: 10.2174/1381612023392937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gendaszewska-Darmach E, Maszewska M, Zaklos M, Koziolkiewicz M. Degradation of extracellular nucleotides and their analogs in HeLa and HUVEC cell cultures. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:973–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SG, Soltysiak KA, Gao ZG, Chang TS, Chung E, Jacobson KA. Tumor necrosis factor α-induced apoptosis in astrocytes is prevented by the activation of P2Y6, but not P2Y4 nucleotide receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:923–931. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mamedova LK, Wang R, Besada P, Liang BT, Jacobson KA. Attenuation of apoptosis in vitro and ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo in mouse skeletal muscle by P2Y6 receptor activation. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korcok J, Raimundo LN, Du X, Sims SM, Dixon SJ. P2Y6 nucleotide receptors activate NF-κB and increase survival of osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16909–16915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koizumi S, Shigemoto-Mogam Y, Nasu-Tada K, Shinozaki Y, Ohsawa K, Tsuda M, Joshi BV, Jacobson KA, Kohsaka S, Inoue K. UDP acting at P2Y6 receptors is a novel mediator of microglial phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;446:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Köttgen M, Löffler T, Jacobi C, Nitschke R, Pavenstädt H, Schreiber R, Frische S, Nielsen S, Leipziger J. P2Y6 receptor mediates colonic NaCl secretion via differential activation of cAMP-mediated transport. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:371–379. doi: 10.1172/JCI200316711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bar I, Guns PJ, Metallo J, Cammarata D, Wilkin F, Boeynams JM, Bult H, Robaye B. Knockout mice reveal a role for P2Y6 receptor in macrophages, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:777–784. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balasubramanian R, Ruiz de Azua I, Wess J, Jacobson KA. Activation of distinct P2Y receptor subtypes stimulates insulin secretion in MIN6 mouse pancreatic beta cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markovskaya A, Crooke A, Guzmán-Aranguez AI, Peral A, Ziganshin AU, Pintor J. Hypotensive effect of UDP on intraocular pressure in rabbits. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;579:93–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Wang Z, Ren H, Yue M, Huang K, Gu H, Liu M, Du B, Qian M. P2Y(6) agonist uridine 5′-diphosphate promotes host defense against bacterial infection via monocytechemoattractant protein-1-mediated monocytes/macrophages recruitment. J Immunol. 2011;86:5376–5387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Tayeb A, Qi A, Nicholas RA, Müller CE. Structural modifications of UMP, UDP, and UTP leading to subtype-selective agonists for P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2878–2890. doi: 10.1021/jm1016297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Tayeb A, Qi A, Müller CE. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of uracil nucleotide derivatives and analogues as agonists at human P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7076–7087. doi: 10.1021/jm060848j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyer JL, Siddiqi S, Fischer B, Romero-Avila T, Jacobson KA, Harden TK. Identification of potent P2Y-purinoceptor agonists that are derivatives of adenosine 5′-monophosphate. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;8:1959–1964. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cristalli G, Podda GM, Costanzi S, Lambertucci C, Lecchi A, Vittori S, Volpini R, Zighetti ML, Cattaneo M. Effects of 5′-phosphate derivatives of 2-hexynyl adenosine and 2-phenylethynyl adenosine on responses of human platelets mediated by P2Yreceptors. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2763–2766. doi: 10.1021/jm0493562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Communi D, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM. Pharmacological characterization of the human P2Y11 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conigrave AD, Lee JY, van der Weyden L, Jiang L, Ward P, Tasevski V, Luttrell BM, Morris MB. Pharmacological profile of a novel cyclicAMP-linked P2 receptor on undifferentiated HL-60 leukemia cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1580–1585. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobson KA, Ivanov AA, de Castro S, Harden TK, Ko H. Development of selective agonists and antagonists of P2Y receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besada P, Shin DH, Costanzi S, Ko H, Mathé C, Gagneron J, Gosselin G, Maddileti S, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Structure-activity relationships of uridine 5′-diphosphate analogues at the human P2Y6 receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5532–5543. doi: 10.1021/jm060485n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costanzi S, Joshi BV, Maddileti S, Mamedova M, Gonzalez-Moa MJ, Marquez VE, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Human P2Y(6) receptor: molecular modeling leads to the rational design of a novel agonist based on a unique conformational preference. J Med Chem. 2005;48:8108–8111. doi: 10.1021/jm050911p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maruoka H, Barrett MO, Ko H, Tosh DK, Melman A, Burianek LE, Balasubramanian R, Berk B, Costanzi S, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Pyrimidine ribonucleotides with enhanced selectivity as P2Y(6) receptor agonists: novel 4-alkyloxyimino, (S)-methanocarba, and 5′-triphosphate gamma-ester modifications. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4488–4501. doi: 10.1021/jm100287t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meltzer D, Ethan O, Arguin G, Nadel Y, Danino O, Lecka J, Sévigny J, Gendron FP, Fischer B. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of uracil nucleotide derivatives towards the identification of human P2Y6 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:5764–5773. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey PA, Sammons RD. Bond order and charge localization in nucleoside phosphorothioates. Science. 1985;228:541–545. doi: 10.1126/science.2984773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Da Costa CP, Okruszek A, Sigel H. Complex formation of divalent ions with uridine 5′-thiomonophosphate or methyl thiophosphate: comparison of complex stabilities with those of the parent phosphate ligands. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:593–602. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200200551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Major DT, Nahum V, Wang Y, Reiser G, Fisher B. Molecular recognition in purinergic receptors. 2. Diastereoselectivity of the h-P2Y1-receptor. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4405–4416. doi: 10.1021/jm049771u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Węgłowska E, Szustak M, Gendaszewska-Darmach E. Proangiogenic properties of nucleoside 5′-O-phosphorothioate analogues under hyperglycaemic conditions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:2464–2474. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150619142859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guga P, Koziołkiewicz M. Phosphorothioate nucleotides and oligonucleotides - recent progress in synthesis and application. Chem Biodivers. 2011;8:1642–1681. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PPTX 124 kb)

(DOC 34 kb)