Abstract

Schizophrenia-related psychosis is associated with disturbances in mesolimbic dopamine (DA) transmission, characterized by hyperdopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway. Currently, the only clinically effective treatment for schizophrenia involves the use of antipsychotic medications that block DA receptor transmission. However, these medications produce serious side effects leading to poor compliance and treatment outcomes. Emerging evidence points to the involvement of a specific phytochemical component of marijuana called cannabidiol (CBD), which possesses promising therapeutic properties for the treatment of schizophrenia-related psychoses. However, the neuronal and molecular mechanisms through which CBD may exert these effects are entirely unknown. We used amphetamine (AMPH)-induced sensitization and sensorimotor gating in rats, two preclinical procedures relevant to schizophrenia-related psychopathology, combined with in vivo single-unit neuronal electrophysiology recordings in the ventral tegmental area, and molecular analyses to characterize the actions of CBD directly in the nucleus accumbens shell (NASh), a brain region that is the current target of most effective antipsychotics. We demonstrate that Intra-NASh CBD attenuates AMPH-induced sensitization, both in terms of DAergic neuronal activity measured in the ventral tegmental area and psychotomimetic behavioral analyses. We further report that CBD controls downstream phosphorylation of the mTOR/p70S6 kinase signaling pathways directly within the NASh. Our findings demonstrate a novel mechanism for the putative antipsychotic-like properties of CBD in the mesolimbic circuitry. We identify the molecular signaling pathways through which CBD may functionally reduce schizophrenia-like neuropsychopathology.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The cannabis-derived phytochemical, cannabidiol (CBD), has been shown to have pharmacotherapeutic efficacy for the treatment of schizophrenia. However, the mechanisms by which CBD may produce antipsychotic effects are entirely unknown. Using preclinical behavioral procedures combined with molecular analyses and in vivo neuronal electrophysiology, our findings identify a functional role for the nucleus accumbens as a critical brain region whereby CBD can produce effects similar to antipsychotic medications by triggering molecular signaling pathways associated with the effects of classic antipsychotic medications. Specifically, we report that CBD can attenuate both behavioral and dopaminergic neuronal correlates of mesolimbic dopaminergic sensitization, via a direct interaction with mTOR/p70S6 kinase signaling within the mesolimbic pathway.

Keywords: cannabidiol, dopamine, mesolimbic system, nucleus accumbens, schizophrenia, ventral tegmental area

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychiatric disorder characterized by delusions, hallucinations, and cognitive filtering disturbances (McGrath et al., 2008). For decades, schizophrenia has been treated using antipsychotic drugs targeting dopamine (DA) receptors. However, there are significant side effects associated with currently available antipsychotics (Awad and Voruganti, 2004), and no mechanistically novel treatment has emerged to replace them. Disturbances in the brains endocannabinoid system are increasingly recognized as etiological factors underlying schizophrenia-related symptoms (Tan et al., 2014). Exposure to extrinsic cannabinoids, such as marijuana (MJ), can induce psychotomimetic effects acutely, or following chronic neurodevelopmental exposure (D'Souza et al., 2004; Renard et al., 2014). Nevertheless, MJ contains a complex mixture of phytochemicals, the two largest being Δ-9-tetra-hydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC and CBD possess highly distinct pharmacological and psychotropic profiles. Whereas THC exposure is associated with psychotomimetic effects, recent evidence suggests that CBD, a nonpsychoactive component of MJ, has promising potential as an antipsychotic treatment.

In preclinical models of schizophrenia, CBD reduces schizophrenia-like behaviors induced by psychotomimetic drugs and has a neuropharmacological profile similar to atypical antipsychotics. For example, CBD is more effective than haloperidol and similar to clozapine, in attenuating ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion (Moreira and Guimarães, 2005). CBD has been shown also to reverse MK-801-induced sensorimotor gating deficits in mice (Long et al., 2006) and MK-801-induced social withdrawal in rats (Gururajan et al., 2011). CBD is comparable with haloperidol in terms of reducing apomorphine-induced hyperlocomotion, but in contrast to haloperidol, is devoid of extrapyramidal side effects, even at high doses (Zuardi et al., 1991). A recent clinical trial has confirmed that CBD possesses properties similar to antipsychotic medications and effectively reduces psychotic symptoms with equal efficacy to traditional medications, but with significantly fewer side effects (Leweke et al., 2012). However, the neuronal and molecular mechanisms through which CBD may exert these effects are entirely unknown.

At the molecular level, considerable evidence links schizophrenia with disturbances in signaling pathways associated with DA receptor function. These include the wingless (Wnt) signal transduction pathway, protein kinase B (Akt), glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), and β-catenin. Importantly, both typical and atypical antipsychotic medications can activate these pathways (Alimohamad et al., 2005b; Sutton et al., 2007; Freyberg et al., 2010). In addition, increasing evidence identifies the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which regulates downstream activity of p70S6 kinase (p70S6K), as a crucial molecular substrate underlying schizophrenia-related psychopathology and antipsychotic efficacy (Gururajan and van den Buuse, 2014; Liu et al., 2015).

In the present study, we used amphetamine (AMPH)-induced sensitization and sensorimotor gating in rats, two preclinical behavioral procedures relevant to schizophrenia-related psychopathology, combined with molecular analyses and in vivo neuronal electrophysiology to characterize the potential antipsychotic-like properties of CBD within the mesolimbic system. We report that CBD attenuates AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization and AMPH-induced sensorimotor gating deficits. Furthermore, we report that CBD produces its effects through modulation of the phosphorylation states of the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathways in the nucleus accumbens shell (NASh). Finally, we demonstrate that CBD within the NASh can normalize AMPH-induced dysregulation of mesolimbic DA neuron activity states.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (300–350 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. At arrival, rats were housed under controlled conditions (12 h light/dark cycle, constant temperature, and humidity) with access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with Governmental and Institutional guidelines for appropriate animal care and experimentation.

Surgical procedures.

Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ketamine (80 mg/ml)-xylazine (6 mg/kg) mixture. Meloxicam (1 mg/kg; s.c.) was administered postoperatively to reduce pain and inflammation. Rats were placed in a Kopf stereotaxic device and stainless steel guide cannulae (22-gauge) were implanted bilaterally into the NASh using flat skull stereotaxic coordinates as follows (12° angle, in mm from bregma): anteroposterior 1.8 mm, lateral ±2.6 mm, dorsoventral −7.4 mm from the dural surface. Guide cannulae were held in place using jeweler's screws and dental acrylic cement. Rats were single-housed after surgeries.

Drug preparation and administration

One week after surgery, rats received Intra-NASh bilateral infusions of CBD (Tocris Bioscience, 100 ng in 20% DMSO and 80% NaCl (0.9%); 0.50 μl per side), vehicle (VEH, 20% DMSO and 80% NaCl (0.9%); 0.50 μl per side), coadministration of Torin2 (Tocris Bioscience, 40 ng in 20% DMSO and 80% NaCl (0.9%); 0.50 μl per side) and CBD (Torin2+CBD) and coadministration of PF 4708671 (PF, Tocris Bioscience, 100 ng in 50% DMSO and 50% NaCl (0.9%); 0.50 μl per side) and CBD (PF+CBD) over 5 consecutive days using an injection cannulae connected to a Hamilton syringe with Teflon tubing and a microinfusion pump. A total volume of 0.5 μl per side was delivered over a period of 1 min. Microinjectors were left in place for an additional 1 min following drug infusion to ensure adequate diffusion from the tip. Immediately following the microinfusions, the rats received an intraperitoneal injection of d-AMPH sulfate (AMPH; Sigma-Aldrich; 5 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl) or VEH (0.9% NaCl). Following the final AMPH or VEH treatment injection (on day 5), rats were left undisturbed in home cages until test day (locomotor activity or prepulse inhibition [PPI]) on sensitization day 16, when rats received the VEH or AMPH challenge (1 mg/kg; i.p.).

AMPH-induced hyperlocomotor activity

Locomotor activity, stereotypy, and rearing counts were recorded for 60 min in an automated open-field activity chamber (Med Associates). The final number of rats in each group was as follows: VEH/Intra-NASh VEH group (VEH/VEH), n = 9; VEH/Intra-NASh CBD group (VEH/CBD), n = 10; AMPH/Intra-NASh VEH group (AMPH/VEH), n = 8; AMPH/Intra-NASh CBD group (AMPH/CBD), n = 10; AMPH/Intra-NASh Torin2+CBD, n = 8; and AMPH/Intra-NASh PF+CBD, n = 8.

Protein extraction and Western blotting

After completion of locomotor sensitization tests, rats received an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (240 mg/kg, i.p., Euthanyl). Under deep anesthesia, rats were decapitated and brains removed and frozen. Coronal sections (60 μm) containing the nucleus accumbens (NAc) were cut on a cryostat and slide mounted. Some sections were stained with cresyl violet for microinfusion site verification with light microscopy. For remaining sections, bilateral micropunches of the NAc, adjacent to, but not including injection sites, were obtained for protein isolation. The Western blotting procedure was performed as described previously (Lyons et al., 2013). Primary antibody dilutions were as follows: α-tubulin (1:120,000; Sigma-Aldrich), phosphorylated GSK-3α/β ser21/9 (p-GSK-3α/β; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), total GSK-3α/β ser21/9 (t-GSK-3α/β; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated Akt Ser473 (p-Akt; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), total Akt (t-Akt; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), β-catenin (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich), phosphorylated mTOR ser2448 (p-mTOR;1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology), total mTOR (t-mTOR; 1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated p70S6K thr389 (p-p70S6K; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), and total p70S6K (t-p70S6K; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific) were all used at a dilution of 1:20,000.

PPI of startle reflex

Rats were acclimated to the startle chambers (Med Associates) for 5 min over 3 d. On the last day of acclimation, rats were tested in an input/output (I/O) function consisting of 12 increasing startle pulses (from 65 to 120 dB, 5 dB increments) to determine the appropriate gain setting for each individual rat. The testing procedure consisted of the following phases: the acclimation phase, a habituation phase (Block 1), and PPI measurement (Block 2). During acclimation, rats were exposed to the chambers and white background noise (68 dB) for 5 min. During Block 1, 10 pulse alone trials (110 dB white noise, 20 ms duration) were delivered at 15–20 s intertrial intervals. Block 2 consisted of 9 different trials presented 10 times in a pseudo-randomized order at 15–20 s intervals: 10 pulse-alone trials, and 10 of each of the three different prepulse-pulse trial types (72, 76, 80) with interstimulus intervals of 30 and 100 ms. Pulse-alone trials consisted of a startle stimulus-only presentation, whereas prepulse-pulse trials consisted of the presentation of a weaker nonstartling prepulse (white noise, 20 ms duration) before the startling stimulus. PPI was calculated for each animal and each trial condition as PPI (%) = (1 − average startle amplitude to pulse with prepulse/average startle amplitude to pulse only) × 100. The final number of rats in each group was as follows: VEH/Intra-NASh VEH group (VEH/VEH), n = 8; VEH/Intra-NASh CBD group (VEH/CBD), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh VEH group (AMPH/VEH), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh CBD group (AMPH/CBD), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh Torin2+CBD, n = 10; and AMPH/Intra-NASh PF +CBD, n = 10.

In vivo ventral tegmental area (VTA) neuronal recordings

AMPH-treated rats received intraperitoneal injections of AMPH (Sigma-Aldrich; 5 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl) over 5 consecutive days. Following the final AMPH treatment injection (on day 5), rats were left undisturbed in their home cages until VTA neuronal activity recordings on sensitization day 16. In vivo intra-VTA single-unit extracellular recordings were performed as described previously (Loureiro et al., 2015), under urethane anesthesia. For challenge administration of AMPH (Sigma-Aldrich; 1 mg/kg; i.p.), a syringe was maintained in place using a 25 G winged infusion set. For Intra-NASh microinfusions of either VEH or CBD, a 1 μl Hamilton syringe was slowly lowered into the NASh using the same stereotaxic coordinates described above. For intra-VTA recordings, glass microelectrodes were lowered to the following coordinates: anteroposterior −5.2 mm from bregma, lateral ±0.8 to 1 mm, dorsoventral −6.5 to −9 mm from the dural surface. Presumptive VTA DA neurons were identified according to the following well-established electrophysiological features (Ungless et al., 2004; Ungless and Grace, 2012): (1) action potential with biphasic or triphasic waveform with duration >1.1 ms from the start of the action potential to the negative trough; (2) a slow spontaneous firing rate (∼2–5 Hz); and (3) a single irregular or bursting firing pattern. The response patterns of isolated VTA neurons following the microinfusions of either CBD or VEH into the NASh and the intraperitoneal injection of the challenge dose of AMPH were determined by comparing neuronal frequency rates between the 6 min of predrug baseline versus each 6 min postadministration recording epochs (i.e., 0–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24, 24–30, and 30–36 min). We also analyzed the proportion of DA neuronal spikes firing in burst mode. The onset of a burst was defined as the occurrence of two consecutive spikes with an interspike interval of <80 ms (Grace and Bunney, 1983). The percentage of spikes firing in burst was calculated by dividing the number of spikes occurring in bursts by the total number of spikes occurring in the same period of time. We sampled a total of n = 19 VTA DA neurons (Intra-NASh VEH group, n = 10 cells in 8 rats; Intra-NASh CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) group, n = 9 cells in 6 rats). Histological analysis were performed as described previously (Loureiro et al., 2015). Cells recorded outside the anatomical boundaries of the VTA were excluded from data analysis.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with one- or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA or t tests where appropriate. Post hoc analyses were performed with Fisher's LSD. Densitometry values for Western blots were obtained with Kodak digital analysis software and analyzed with t tests.

Results

Intra-NASh CBD attenuates AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization

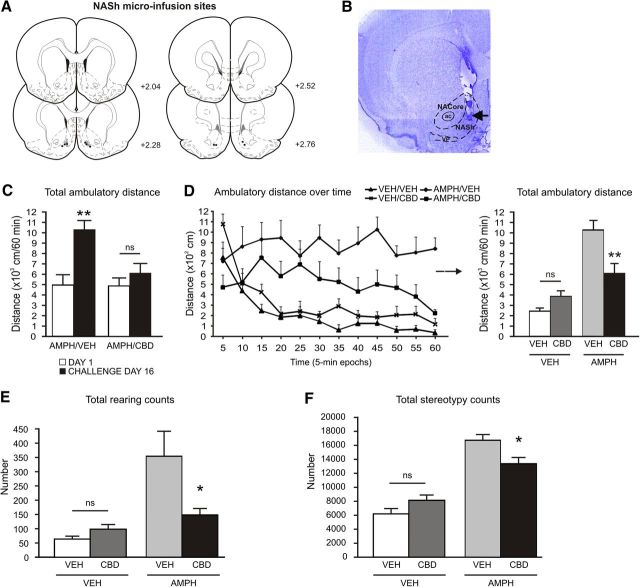

Using a classic model of AMPH-induced DAergic sensitization, we first challenged the effects of AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization with bilateral Intra-NASh microinfusions of CBD or VEH (Fig. 1A,B). Our selected dose of CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) was chosen following Intra-NASh dose–response behavioral analyses showing it to be the highest behaviorally effective dose, without producing motoric side effects. Comparing locomotor activity on day 1 versus challenge day 16, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the factor day (F(1,35) = 18.859; p < 0.001) and a significant interaction between the factors treatment and day (F(1,35) = 7.437; p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed that repeated exposure to AMPH (5 mg/kg) followed by an 11 day sensitization period caused a typical pattern of AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats (p < 0.01; Fig. 1C), although it did not produce such effects in Intra-NASh CBD pretreated rats (p > 0.05; Fig. 1C). Furthermore, when comparing both doses of acute AMPH (1 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg), our pilot studies showed that Intra-NASh VEH animals receiving an acute dose of AMPH of 1 mg/kg displayed no significant differences in terms of locomotor ambulatory activity or vertical counts, relative to Intra-NASh VEH rats receiving the dose of 5 mg/kg of AMPH on day 1 (t(14) = 1.105; p > 0.05; and t(14) = 0.174; p > 0.05; respectively; data not shown). Ambulatory activity assessed in 5 min epochs over the 60 min recording session on the test day 16 is shown in Figure 1D. One-way ANOVA analysis of locomotor activity revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(3,36) = 18.711; p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in VEH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment had no effects on locomotor activity relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p > 0.05; Fig. 1D). However, in AMPH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment attenuated AMPH-induced hyperlocomotor activity relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 1D). Analysis of rearing revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(3,36) = 9.262; p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in VEH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment had no effects on rearing counts relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p > 0.05; Fig. 1E). However, in AMPH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreased AMPH-induced rearing relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 1E). Analysis of stereotypy counts revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(3,36) = 31.184; p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in VEH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment had no effects on stereotypy counts relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p > 0.05; Fig. 1F). However, in AMPH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreased AMPH-induced stereotypy relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 1F). Thus, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment attenuated AMPH-induced behavioral psychomotor sensitization phenomena.

Figure 1.

Effects of Intra-NASh VEH versus CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) pretreatment on AMPH-induced hyperlocomotion. A, Schematic representations of microinfusion locations in the NASh of AMPH-sensitized rats. Black circles represent CBD (100 ng). Gray circle represents VEH. B, Microphotograph of a representative Intra-NASh injector placement. C, Exposure to AMPH (5 d, 5 mg/kg) followed by an 11 day sensitization period caused a typical pattern of AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. D, Ambulatory activity assessed in 5 min epochs over the 60 min recording session and total ambulatory activity. Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases the AMPH-induced locomotor activity observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. E, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases AMPH-induced rearing observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. F, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases AMPH-induced stereotypy observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. VEH/ Intra-NASh VEH, n = 9; VEH/Intra-NASh CBD, n = 10; AMPH/Intra-NASh CBD, n = 10; AMPH/Intra-Nash VEH, n = 8. **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA). ns, Not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. ac, Anterior commissure; NACore, core subdivision of the nucleus accumbens; VP, ventral pallidum.

Intra-NASh CBD increases phosphorylation of mTOR and p70S6K in AMPH-sensitized rats

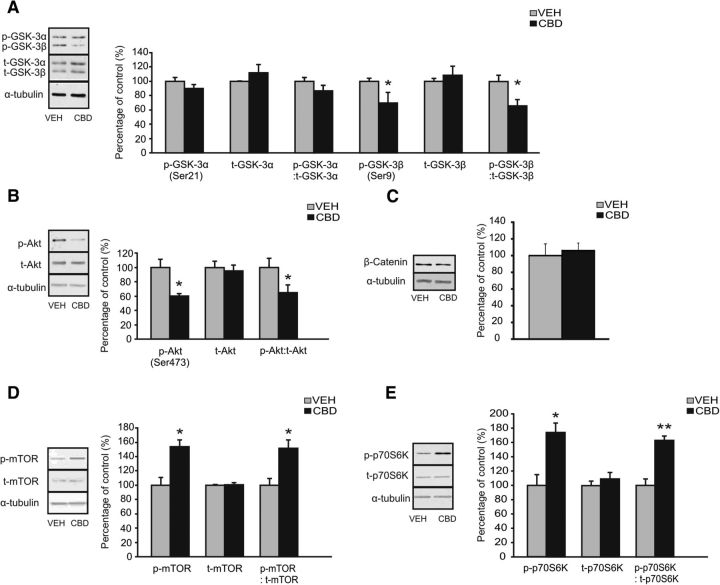

To examine whether CBD may produce its putative antipsychotic-like actions through previously identified, canonical antipsychotic molecular pathways, we analyzed expression levels of Akt/Wnt-related (i.e., β-catenin, GSK-3, Akt) or mTOR signaling pathways (i.e., p70S6K and mTOR expression), comparing Intra-NASh VEH versus CBD-pretreated rats from our previous AMPH sensitization studies. Western blot analyses revealed a significant decrease in levels of phosphorylated GSK-3β (p-GSK-3β) (t(9) = 2.01; p < 0.05) and the ratio of p-GSK-3β/total-GSK-3β expression (t(9) = 2.56; p < 0.05) when comparing Intra-NASh VEH- versus Intra-NASh CBD-AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 2A). Expression of total GSK-3β protein levels (t-GSK-3β), p-GSK-3α, t-GSK-3α, and p-GSK-3α/t-GSK-3α were unaffected (p > 0.05; Fig. 2A). We further found a significant decrease in levels of phosphorylated Akt Ser473 (p-Akt) (t(8) = 3.09; p < 0.05) and the ratio of p-Akt/total-Akt expression (t(8) = 2.05; p < 0.05) between groups (Fig. 2B). Expression of total Akt protein levels (t-Akt) was unaffected (t(8) = 0.38; p > 0.05; Fig. 2B). In contrast, β-catenin expression levels did not differ between groups (t(6) = −0.35; p > 0.05) (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Western blot analyses revealed a significant increase in levels of phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) (t(6) = −3.60; p < 0.05) and the ratio of p-mTOR/total-mTOR expression (t(6) = −3.35; p < 0.05) when comparing Intra-NASh VEH- versus Intra-NASh CBD-AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 2D). Expression of total mTOR protein levels (t-mTOR) was unaffected (t(6) = −0.39; p > 0.05; Fig. 2D). We further found significantly increased levels of phosphorylated-p70S6K (p-p70S6K) (t(6) = −3.70; p < 0.05) and in the ratio of p-p70S6K/total-p70S6K expression (t(6) = −5.94; p < 0.01) when comparing Intra-NASh VEH- versus Intra-NASh CBD-AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 2E). Expression of total p70S6K protein levels (t-p70S6K) was unaffected (t(6) = −0.79; p > 0.05; Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Effects of chronic Intra-NASh VEH or CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) pretreatment on NAc expression levels of members of the Wnt (GSK-3, Akt, β-catenin) and mTORC1 (mTOR, p70S6K) signal transduction pathway in AMPH-sensitized rats. A, Representative Western blot for phosphorylated and total GSK-3α and GSK-3β expression in the NAc (left). Densitometry analysis revealed a decrease in both phosphorylated GSK-3β and the ratio of phosphorylated to total GSK-3β in Intra-NASh CBD compared with Intra-NASh VEH AMPH-sensitized rats. No significant changes in total GSK-3β, and other levels of GSK-3α are observed. B, Representative Western blot for phosphorylated and total Akt expression in the NAc (left). Densitometry analysis revealed a decrease in both phosphorylated Akt and the ratio of phosphorylated to total Akt in Intra-NASh CBD- compared with Intra-NASh VEH AMPH-sensitized rats. No significant changes in total Akt are observed. C, Representative Western blot for β-catenin expression in the NAc (left). No significant changes in β-catenin expression are observed between Intra-NASh VEH- and CBD-AMPH-sensitized rats. D, Representative Western blot for phosphorylated and total mTOR expression in the NAc (left). Densitometry analysis revealed an increase in both phosphorylated mTOR and the ratio of phosphorylated to total mTOR in Intra-NASh CBD- compared with Intra-NASh VEH AMPH-sensitized rats. No significant changes in total mTOR are observed. E, Representative Western blot for phosphorylated and total p70S6K expression in the NAc (left). Densitometry analysis revealed an increase in both phosphorylated p70S6K and the ratio of phosphorylated to total p70S6K in Intra-NASh CBD- compared with Intra-NASh VEH AMPH-sensitized rats. No significant changes in total p70S6K are observed. **p < 0.01 (t test). *p < 0.05 (t test). Error bars indicate SEM.

Inhibition of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway blocks the effects of CBD on AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization phenomena

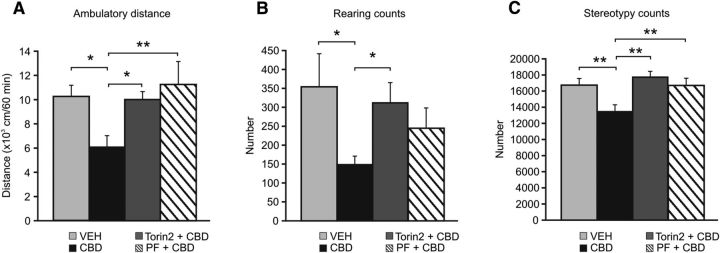

Given our findings that Intra-NASh CBD selectively activated the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathways in AMPH-sensitized rats, we next sought to demonstrate the functionality of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway by examining whether Intra-NASh pharmacological blockade of either mTOR or p70S6K signaling could reverse the putative antipsychotic-like effects of CBD. Using our above-described AMPH sensitization protocol, we coadministered CBD+Torin2 (a selective mTOR inhibitor) or CBD+PF 4708671 (PF; a novel and selective inhibitor of p70S6K) (Pearce et al., 2010) via bilateral Intra-NASh infusions. The selected dose of Torin2 (40 ng/0.5 μl) was chosen based upon pilot studies demonstrating that this dose produced robust hyperlocomotor activity via intra-NAc infusion. Analysis of locomotor activity revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(3,33) = 3.99; p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed, as before, that Intra-NASh CBD attenuated AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization relative to VEH controls (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Remarkably, Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reversed the effects of CBD (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 3A). Analysis of rearing revealed a slight, although nonsignificant, effect of treatment (F(3,33) = 2.75; p = 0.059). Post hoc comparisons revealed that Intra-NASh CBD significantly decreased AMPH-induced rearing relative to VEH controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). Similarly, Intra-NASh Torin2 significantly reversed CBD-mediated attenuation of AMPH-induced rearing (p < 0.05), whereas Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with PF had no effect (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3B). Analysis of stereotypy counts revealed a significant treatment effect (F(3,33) = 5.33; p < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons revealed, as before, that Intra-NASh CBD significantly decreased AMPH-induced stereotypy relative to controls (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reversed CBD-mediated attenuation of AMPH-induced stereotypies (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Effects of Intra-NASh VEH, -CBD, -CBD+Torin2 or -CBD+PF 4708671 (PF) pretreatment on AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization. A, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases AMPH-induced locomotor activity observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reverses CBD-induced decreases in hyperactivity. B, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases AMPH-induced rearing observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with Torin2 significantly reverses CBD-induced attenuation in rearing, whereas Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with PF has no effect. C, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases AMPH-induced stereotypies observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reverses CBD-induced decrease in stereotypy levels. Intra-NASh CBD, n = 10; Intra-Nash VEH, n = 8; Intra-NASh Torin2+CBD, n = 8; Intra-NASh PF+CBD, n = 8. The Intra-Nash CBD and VEH groups are the same as those shown in Figure 1. **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA). Error bars indicate SEM.

Inhibition of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway blocks the effects of CBD on AMPH-induced sensorimotor gating deficits

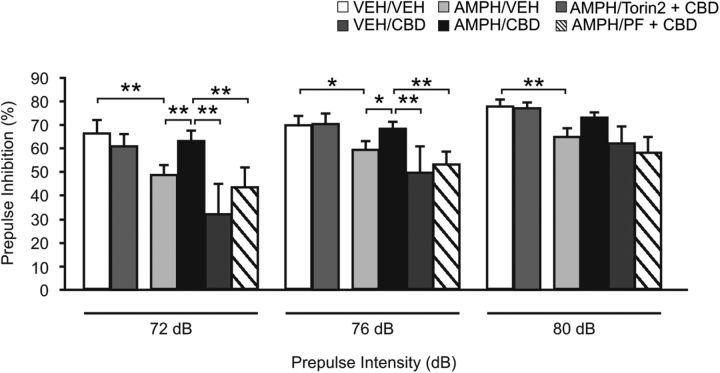

We next evaluate the putative antipsychotic-like effects of Intra-NASh CBD and the functionality of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway using the PPI test. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA on PPI responses revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(5,164) = 2.83; p < 0.05) and a significant effect of prepulse intensity factor (F(2,164) = 46.50; p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in VEH-treated rats, Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment had no effects on PPI responses relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p > 0.05; Fig. 4). In AMPH-treated rats, repeated exposure to AMPH (5 mg/kg) followed by an 11 day sensitization period induced deficits in PPI in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats at the prepulse intensity levels of 72, 76, and 80 dB (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 4). Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment reversed AMPH-induced PPI deficits relative to Intra-NASh VEH controls (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 4) at the prepulse intensity levels of 72 and 76 dB. Remarkably, Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reversed the effects of CBD on PPI responses observed at 72 and 76 dB (p values <0.01; Fig. 4). Importantly, the startle amplitude responses were unchanged between groups (F(5,54) = 1.01; p > 0.05) (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of Intra-NASh VEH, -CBD, -CBD+Torin2 or - CBD+PF 4708671 (PF) pretreatment on AMPH-induced PPI deficit. Exposure to AMPH (5 d, 5 mg/kg) followed by an 11 day sensitization period caused PPI deficit in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly decreases the AMPH-induced PPI deficit observed in Intra-NASh VEH-pretreated rats. Intra-NASh CBD cotreatment with either Torin2 or PF significantly reverses CBD-induced increases in PPI. VEH/Intra-NASh VEH (VEH/VEH), n = 8; VEH/Intra-NASh CBD (VEH/CBD), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh VEH (AMPH/VEH), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh CBD (AMPH/CBD), n = 9; AMPH/Intra-NASh Torin2+CBD (AMPH/Torin2+CBD), n = 10; and AMPH/Intra-NASh PF +CBD (AMPH/PF+CBD), n = 10. **p < 0.01 (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). *p < 0.05 (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). Error bars indicate SEM.

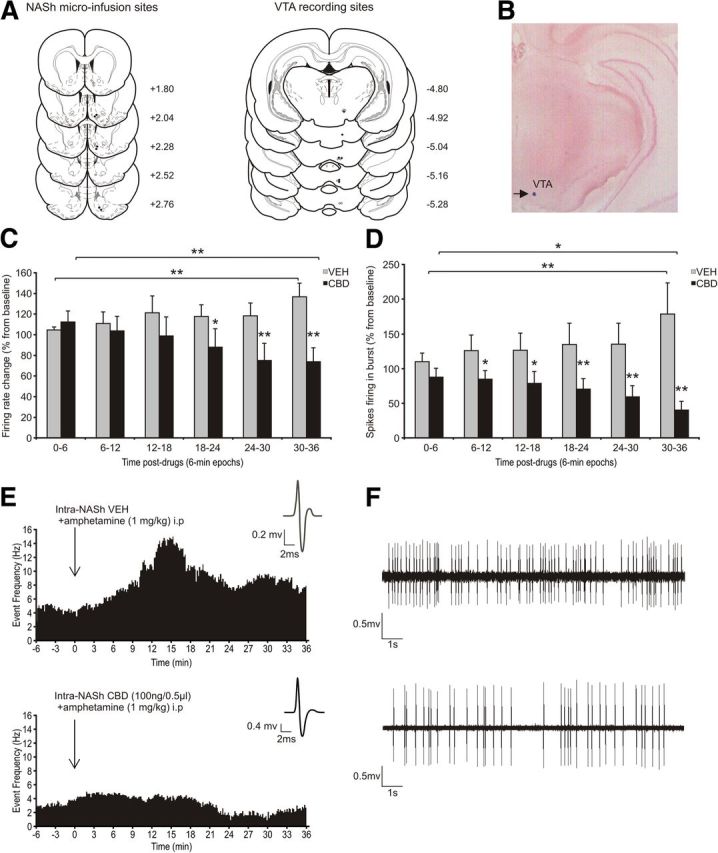

Effects of Intra-NASh CBD on VTA DA neuronal sensitization

Finally, given the ability of Intra-NASh CBD to attenuate behavioral effects of AMPH sensitization, we next sought to determine whether Intra-NASh CBD may also counteract neuronal VTA DA sensitization effects. Schematic representations of VTA neuronal recording sites and microinfusion locations in the NASh are shown in Figure 5A. A microphotograph of a representative VTA neuronal recording placement is shown in Figure 5B. Two-way ANOVA comparing firing frequency rates relative to preinfusion baseline levels showed a significant interaction between treatment (VEH vs CBD) and recording epoch time (F(5,113) = 4.17, p < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons showed that following AMPH challenge, VEH rats displayed significantly increased VTA DA neuronal firing frequency rates beginning at 30 min after AMPH (p < 0.01; Fig. 5C). Conversely, Intra-NASh CBD-treated rats displayed significantly decreased VTA DA neuronal firing frequency (p < 0.01) at 30 min after AMPH (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, frequency rates in CBD versus VEH-treated DA neurons were significantly lower at the 18–24 min epoch (p < 0.05), and all subsequent time-point comparisons (p values <0.01; Fig. 5C). Comparing DA neuron spikes firing in bursting mode, two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction between treatment (VEH vs CBD) and recording epoch time (F(5,107) = 4.12, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5D). Post hoc comparisons demonstrated that, whereas VEH-treated neurons showed significantly increased bursting levels relative to baseline beginning 30 min after AMPH (p < 0.01), Intra-NASh CBD-treated neurons were significantly decreased at this same time point (p < 0.05; Fig. 5D). In addition, DA neuron bursting levels were significantly lower in CBD versus VEH-treated neurons at the 6–12 min epoch (p < 0.05), and all subsequent comparison time-points (p values <0.01; Fig. 5D). Sample VTA DA neuronal recording traces from VEH or CBD-treated neurons after AMPH exposure are presented in Figure 5E, F. Thus, Intra-NASh CBD effectively attenuated AMPH-induced VTA DA neuronal sensitization effects both in terms of firing frequency and bursting levels.

Figure 5.

Effects of Intra-NASh VEH versus CBD on VTA DA neuronal activity following AMPH challenge. A, Histological localization of microinfusion sites in the NASh and recording sites in the VTA for each treatment condition performed during electrophysiological recordings. Black circles represent CBD (100 ng). Gray circle represents VEH. A total of n = 19 VTA DA neurons were sampled: Intra-NASh VEH group, n = 10 cells in 8 rats; Intra-NASh CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) group, n = 9 cells in 6 rats. B, Microphotograph of a representative VTA neuronal recording placement. C, Time-dependent consequences of Intra-NASh VEH and CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) treatments on VTA DA neuronal firing frequency following the challenge dose of systemic AMPH (1 mg/kg). D, Time-dependent consequences of Intra-NASh VEH and CBD (100 ng/0.5 μl) treatments on VTA DA spikes firing in burst mode following AMPH challenge. E, Representative histogram showing the increase response activity of one DA neuron following the microinfusion of Intra-NASh VEH and systemic AMPH (top) or Intra-NASh CBD and systemic AMPH (bottom). Inset, Action potential waveform of the selected neuron. F, Activity patterns observed 20 min after the microinfusions of either Intra-NASh VEH (top) or CBD (bottom) and systemic AMPH. **p < 0.01 (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). *p < 0.05 (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

The phytochemical complexity of MJ is revealed by both clinical and preclinical evidence demonstrating that THC and CBD can produce opposing effects on both mesolimbic neuronal function, and neuropsychiatric phenomena. However, little is currently known about how CBD modulates the mesolimbic system, particularly in the context of DAergic function. Whereas THC is primarily associated with propsychotic effects (D'Souza et al., 2004; Kuepper et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2014), CBD has been shown to counteract the psychotomimetic properties of THC and significantly improve psychosis symptoms in schizophrenia patients (Leweke et al., 2012; Englund et al., 2013). For example, using fMRI imaging, Bhattacharyya et al. (2009) reported that disruption of cognitive processing by THC administration in otherwise healthy subjects, was blocked by coadministration of CBD. Interestingly, CBD also blocked dysregulation of striatal activation patterns induced by acute THC administration. Similarly, Englund et al. (2013) reported that pretreatment with CBD before acute administration of THC was able to attenuate psychosis-like effects of THC, further demonstrating the potential for CBD-mediated antipsychotic applications. Nevertheless, the underlying neuronal and/or molecular mechanisms by which CBD may produce these effects have thus far not been identified.

In the present study, we demonstrate a novel molecular and neuronal mechanism for the putative antipsychotic-like effects of CBD, within the mesolimbic system. Using a well-established and validated animal model of DAergic sensitization, we found that CBD acting in the NASh, a neural region critical for antipsychotic efficacy, attenuated AMPH-induced sensitization, in terms of psychotomimetic behaviors (hyperlocomotion and sensorimotor gating deficits) and DAergic neuronal activity within the VTA. In addition, we found that the effects of CBD were dependent upon the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway, as Intra-NASh CBD selectively increased the phosphorylation states of these signaling pathways, whereas directly blocking these molecular effects in the NASh was sufficient to reverse the effects of CBD on DA-dependent, psychomotor sensitization behaviors and PPI deficits. Although the present study focused exclusively on the NAc, the effects of CBD on the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway may be related to other NAc output targets, such as the prefrontal cortex and/or the VTA.

The endogenous DA sensitization hypothesis postulates that a sensitized DA system is intrinsic to schizophrenia and leads to the development of schizophrenia-related psychopathology (Lieberman et al., 1997; Laruelle, 2000; Abi-Dargham and Laruelle, 2005). This can be modeled in humans and rodents using chronic AMPH administration, which sensitizes the mesolimbic DA pathway (both in terms of psychomotor activity and neuronal activity levels) to subsequent “challenge” administration of AMPH. Indeed, in human subjects, intermittent AMPH exposure leads to neural and cognitive alterations similar to those observed in schizophrenia (O'Daly et al., 2014a, b). In rodents, psychomotor sensitization following chronic systemic AMPH administration leads to enduring, sensitized responses to subsequent AMPH challenge (Pierce and Kalivas, 1997; Peleg-Raibstein et al., 2008). In the context of cannabinoid transmission and schizophrenia, this model is appropriate for several reasons. First, both clinical and preclinical evidence demonstrates that the psychotomimetic effects of MJ are mediated by increased DA release within the mesolimbic pathway (Kuepper et al., 2010, 2013). Second, chronic THC administration has been shown to sensitize mesolimbic DA receptor sensitivity (Ginovart et al., 2012). Furthermore, AMPH sensitization transcends species barriers as a model for schizophrenia-like mesolimbic DAergic abnormalities. Finally, AMPH sensitization induces sensorimotor gating deficits measured in the PPI procedure (Tenn et al., 2003; Peleg-Raibstein et al., 2006, 2008). PPI is used to measure sensorimotor gating (i.e., the ability to filter extraneous sensory information to attend to salient environmental stimuli). Deficits in sensorimotor gating are a well-established endophenotype of schizophrenia (Braff and Geyer, 1990), and antipsychotic drugs, such as haloperidol, clozapine, and risperidone, prevent PPI disruption (Geyer et al., 2001).

Intra-NASh CBD pretreatment significantly attenuated AMPH-induced behavioral psychomotor sensitization and PPI deficit phenomena. These effects are consistent with previous findings using classical antipsychotic drugs (Meng et al., 1998; O'Neill and Shaw, 1999; Geyer et al., 2001; Herrera et al., 2013), further demonstrating the putative antipsychotic-like efficacy of CBD. Thus, the present findings demonstrating a strong counter sensitization effect of CBD directly within the mesolimbic pathway is consistent with current theories and evidence emphasizing the importance of DAergic dysfunction as a critical underlying variable in schizophrenia and cannabis-related psychotomimetic effects (Di Forti et al., 2007; Luzi et al., 2008).

The molecular pathways underlying the psychotropic properties of cannabinoids are not entirely understood. In the present study, we focused on several signaling pathways known to be dysregulated in schizophrenia and which have also been linked to antipsychotic efficacy, within the mesolimbic system. Specifically, we examined the direct effects of Intra-NASh CBD on the expression levels of the (Wnt) signal transduction pathway, protein kinase B (Akt), GSK-3, and β-catenin. In addition, we examined the mTOR and p70S6-kinase signaling pathways, both of which are dysregulated in neuropsychiatric disorders, and are modulated by typical and atypical antipsychotic medications (Emamian et al., 2004; Alimohamad et al., 2005b; Sutton et al., 2007; Freyberg et al., 2010; Jernigan et al., 2011; Gururajan and van den Buuse, 2014; Liu et al., 2015).

In contrast to the well-characterized signaling effects of traditional antipsychotic medications, which typically increase mesolimbic phosphorylation levels of Akt/Wnt-related signaling pathways (e.g., protein kinase B [Akt], GSK-3, and β-catenin) (Alimohamad et al., 2005a, b; Sutton et al., 2007; Freyberg et al., 2010), we found that CBD selectively activates mTOR signaling and downstream p70S6K to counteract AMPH-induced psychomotor sensitization effects and PPI deficits. Interestingly, this effect was not dependent on upstream mTOR-activating substrates, such as Akt or its downstream target GSK-3. Indeed, we observed significant downregulation of these molecules, suggesting that CBD may bypass the striatal Akt-GSK-3 signaling pathways to increase phosphorylation levels of mTOR and p70S6K. These findings provide further evidence for a novel mechanistic effect underlying CBD's putative antipsychotic-like properties, directly in the NASh. One interesting implication is that the observed molecular signaling differences between CBD versus traditional antipsychotic medications may in part explain the reported lack of adverse side effects associated with CBD, in both clinical and preclinical studies (Zuardi et al., 1991; Leweke et al., 2012).

Evidence implicating mTOR signaling as a critical regulator of synaptic plasticity, memory, and neuronal morphology (Antion et al., 2008; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010; Jernigan et al., 2011) has been growing over the past decade. Several clinical and preclinical studies have linked dysregulated mTOR signaling with neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia (Li et al., 2010; Jernigan et al., 2011; Bonito-Oliva et al., 2013; Gururajan and van den Buuse, 2014; Liu et al., 2015). For example, a significant reduction in mTOR/p70S6K signaling was observed in the prefrontal cortex of patients with major depressive disorder relative to controls (Jernigan et al., 2011). In addition, the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine has been reported to have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant-like effects in patients with major depressive disorder (Berman et al., 2000), and preclinical studies suggest that this effect is mediated by mTOR activation (Li et al., 2010). Furthermore, in a developmental animal model of schizophrenia, it has been reported that early postnatal treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 affects mTOR/p70S6K-related pathways in the frontal cortex of the adult rat brain (Kim et al., 2010). Interestingly, we recently demonstrated that chronic THC exposure during adolescence in rats induces schizophrenia-like behaviors and decreases mTOR-p70S6K signaling pathway in the prefrontal cortex of adult rat brains, demonstrating that CBD and THC can induce opposite functional effects within these signaling pathways (Renard et al., 2016). Consistent with our findings with CBD, antipsychotic medications have been recently reported to increase mTOR and p70S6K signaling through direct actions on DA D2-selective neuronal populations in the striatum. For example, the typical antipsychotic haloperidol selectively increases phosphorylation levels of p70S6K in D2R-expressing striatal medium spiny neurons (Valjent et al., 2011). While future studies are required to identify the neuronal and pharmacological targets of CBD within the NASh, this evidence suggests that CBD and haloperidol may share a common striatal molecular target, by causing increased phosphorylation of the mTOR-p70S6K signaling pathway.

In terms of the potential mechanistic actions of CBD within the mesolimbic system, the VTA and NAc share functional and reciprocal connections via DAergic and GABAergic afferents from the VTA, and GABAergic efferents from subpopulations of NAc medium spiny neurons projecting back to the VTA (Kalivas and Duffy, 1993; Lu et al., 1998; Usuda et al., 1998; Carr and Sesack, 2000; Tripathi et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2011). Specifically, NAc GABAergic projections target GABAergic VTA neurons through GABAA receptor substrates (Xia et al., 2011). This projection is thought to mediate a “long-loop” inhibitory feedback to regulate VTA DA neurons (Einhorn et al., 1988; Rahman and McBride, 2000; Xia et al., 2011). Consistent with functional effects within this circuitry, we report that Intra-NASh CBD effectively blocked AMPH-induced VTA DA neuronal sensitization effects both in terms of firing frequency and bursting levels. Thus, while future studies are required to address these issues, one possibility is that intra-NASH CBD may inhibit VTA projecting medium spiny neurons, thereby removing tonic inhibitory tone onto non-DAergic VTA neurons.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrate, at the behavioral, molecular, and neuronal levels of analysis, direct mechanistic effects of CBD linked to antipsychotic-like phenomena within the mesolimbic pathway. CBD attenuates DAergic sensitization phenomena within the mesolimbic pathway, the primary brain target for antipsychotic efficacy. Furthermore, we demonstrate a novel mechanistic pathway though which CBD may exert its antipsychotic-like properties. These findings have critical implications not only for understanding how specific phytochemical components of MJ may differentially impact neuropsychiatric phenomena, but demonstrate a potential mechanism for the therapeutic effects of MJ derivatives in the treatment of DA-related, psychiatric disorders.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP 246144 and the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Mechanisms of action of second generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: insights from brain imaging studies. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimohamad H, Rajakumar N, Seah YH, Rushlow W. Antipsychotics alter the protein expression levels of beta-catenin and GSK-3 in the rat medial prefrontal cortex and striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005a;57:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimohamad H, Sutton L, Mouyal J, Rajakumar N, Rushlow WJ. The effects of antipsychotics on B-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase-3 and dishevelled in the ventral midbrain of rats. J Neurochem. 2005b;95:513–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antion MD, Merhav M, Hoeffer CA, Reis G, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Schuman EM, Rosenblum K, Klann E. Removal of S6K1 and S6K2 leads to divergent alterations in learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. Learn Mem. 2008;15:29–38. doi: 10.1101/lm.661908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. Impact of atypical antipsychotics on quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:877–893. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–354. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S, Morrison PD, Fusar-Poli P, Martin-Santos R, Borgwardt S, Winton-Brown T, Nosarti C, O' Carroll CM, Seal M, Allen P, Mehta MA, Stone JM, Tunstall N, Giampietro V, Kapur S, Murray RM, Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Atakan Z, McGuire PK. Opposite effects of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on human brain function and psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35:764–774. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonito-Oliva A, Pallottino S, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Girault JA, Valjent E, Fisone G. Haloperidol promotes mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 via dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa and inhibition of protein phosphatase-1. Neuropharmacology. 2013;72:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA. Sensorimotor gating and schizophrenia: human and animal model studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:181–188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810140081011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Forti M, Lappin JM, Murray RM. Risk factors for schizophrenia–all roads lead to dopamine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(Suppl 2):S101–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza DC, Perry E, MacDougall L, Ammerman Y, Cooper T, Wu YT, Braley G, Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1558–1572. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn LC, Johansen PA, White FJ. Electrophysiological effects of cocaine in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system: studies in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1988;8:100–112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES, Hall D, Birnbaum MJ, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund A, Morrison PD, Nottage J, Hague D, Kane F, Bonaccorso S, Stone JM, Reichenberg A, Brenneisen R, Holt D, Feilding A, Walker L, Murray RM, Kapur S. Cannabidiol inhibits THC-elicited paranoid symptoms and hippocampal-dependent memory impairment. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:19–27. doi: 10.1177/0269881112460109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyberg Z, Ferrando SJ, Javitch JA. Roles of the Akt/GSK-3 and Wnt signaling pathways in schizophrenia and antipsychotic drug action. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:388–396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginovart N, Tournier BB, Moulin-Sallanon M, Steimer T, Ibanez V, Millet P. Chronic Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol exposure induces a sensitization of dopamine D2/3 receptors in the mesoaccumbens and nigrostriatal systems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2355–2367. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. Intracellular and extracellular electrophysiology of nigral dopaminergic neurons-1: identification and characterization. Neuroscience. 1983;10:301–315. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururajan A, van den Buuse M. Is the mTOR-signalling cascade disrupted in schizophrenia? J Neurochem. 2014;129:377–387. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururajan A, Taylor DA, Malone DT. Effect of cannabidiol in a MK-801-rodent model of aspects of Schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera AS, Casanova JP, Gatica RI, Escobar F, Fuentealba JA. Clozapine pre-treatment has a protracted hypolocomotor effect on the induction and expression of amphetamine sensitization. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA, Klann E. mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan CS, Goswami DB, Austin MC, Iyo AH, Chandran A, Stockmeier CA, Karolewicz B. The mTOR signaling pathway in the prefrontal cortex is compromised in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1774–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P. Time course of extracellular dopamine and behavioral sensitization to cocaine: II. Dopamine perikarya. J Neurosci. 1993;13:276–284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00276.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Park HG, Kim HS, Ahn YM, Kim YS. Effects of neonatal MK-801 treatment on p70S6K-S6/eIF4B signal pathways and protein translation in the frontal cortex of the developing rat brain. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:1233–1246. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709991192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuepper R, Morrison PD, van Os J, Murray RM, Kenis G, Henquet C. Does dopamine mediate the psychosis-inducing effects of cannabis? A review and integration of findings across disciplines. Schizophr Res. 2010;121:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuepper R, Ceccarini J, Lataster J, van Os J, van Kroonenburgh M, van Gerven JMA, Marcelis M, van Laere K, Henquet C. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced dopamine release as a function of psychosis risk: 18F-fallypride positron emission tomography study. PLoS One 8. 2013;8:e70378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leweke FM, Piomelli D, Pahlisch F, Muhl D, Gerth CW, Hoyer C, Klosterkötter J, Hellmich M, Koethe D. Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e94. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. The role of endogenous sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: implications from recent brain imaging studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:371–384. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, Banasr M, Dwyer JM, Iwata M, Li XY, Aghajanian G, Duman RS. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329:959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1190287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Sheitman BB, Kinon BJ. Neurochemical sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: deficits and dysfunction in neuronal regulation and plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:205–229. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Pham X, Zhang L, Chen P, Burzynski G, Mcgaughey DM, He S, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Fallin MD, Pierce MS, Mccallion AS, Pulver AE, Avramopoulos D, Valle D. Functional variants in DPYSL2 sequence increase risk of schizophrenia and suggest a link to mTOR signaling. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:61–72. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.015636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long LE, Malone DT, Taylor DA. Cannabidiol reverses MK-801-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:795–803. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro M, Renard J, Zunder J, Laviolette SR. Hippocampal cannabinoid transmission modulates dopamine neuron activity: impact on rewarding memory formation and social interaction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:1436–1447. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. Expression of D1 receptor, D2 receptor, substance P and enkephalin messenger RNAs in the neurons projecting from the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 1998;82:767–780. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzi S, Morrison PD, Powell J, di Forti M, Murray RM. What is the mechanism whereby cannabis use increases risk of psychosis? Neurotox Res. 2008;14:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF03033802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons D, de Jaeger X, Rosen LG, Ahmad T, Lauzon NM, Zunder J, Coolen LM, Rushlow W, Laviolette SR. Opiate exposure and withdrawal induces a molecular memory switch in the basolateral amygdala between ERK1/2 and CaMKIIα-dependent signaling substrates. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14693–14704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1226-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng ZH, Feldpaush DL, Merchant KM. Clozapine and haloperidol block the induction of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine and associated genomic responses in rats. Mol Brain Res. 1998;61:39–50. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00196-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA, Guimarães FS. Cannabidiol inhibits the hyperlocomotion induced by psychotomimetic drugs in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;512:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Daly OG, Joyce D, Tracy DK, Azim A, Stephan KE, Murray RM, Shergill SS. Amphetamine sensitization alters reward processing in the human striatum and amygdala. PLoS One 9. 2014a;9:e9395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Daly OG, Joyce D, Tracy DK, Stephan KE, Murray RM, Shergill S. Amphetamine sensitisation and memory in healthy human volunteers: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Psychopharmacol. 2014b;28:857–865. doi: 10.1177/0269881114527360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill MF, Shaw G. Comparison of dopamine receptor antagonists on hyperlocomotion induced by cocaine, amphetamine, MK-801 and the dopamine D1 agonist C-APB in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145:237–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Alton GR, Richter DT, Kath JC, Lingardo L, Chapman J, Hwang C, Alessi DR. Characterization of PF-4708671, a novel and highly specific inhibitor of p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K1) Biochem J. 2010;431:245–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg-Raibstein D, Sydekum E, Russig H, Feldon J. Withdrawal from repeated amphetamine administration leads to disruption of prepulse inhibition but not to disruption of latent inhibition. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:1323–1336. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg-Raibstein D, Knuesel I, Feldon J. Amphetamine sensitization in rats as an animal model of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:192–216. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, McBride WJ. Feedback control of mesolimbic somatodendritic dopamine release in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2000;74:684–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard J, Krebs MO, Le Pen G, Jay TM. Long-term consequences of adolescent cannabinoid exposure in adult psychopathology. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:361. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard J, Rosen LG, Loureiro M, De Oliveira C, Schmid S, Rushlow WJ, Laviolette SR. Adolescent cannabinoid exposure induces a persistent sub-cortical hyper-dopaminergic state and associated molecular adaptations in the prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv335. Advance online publication. Retrieved Jan. 4, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton LP, Honardoust D, Mouyal J, Rajakumar N, Rushlow WJ. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway by the antipsychotics haloperidol and clozapine involves dishevelled-3. J Neurochem. 2007;102:153–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H, Ahmad T, Loureiro M, Zunder J, Laviolette SR. The role of cannabinoid transmission in emotional memory formation: implications for addiction and schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:73. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenn CC, Fletcher PJ, Kapur S. Amphetamine-sensitized animals show a sensorimotor gating and neurochemical abnormality similar to that of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:103–114. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A, Prensa L, Cebrián C, Mengual E. Axonal branching patterns of nucleus accumbens neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4649–4673. doi: 10.1002/cne.22484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Grace AA. Are you or aren't you? Challenges associated with physiologically identifying dopamine neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science. 2004;303:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuda I, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens in the rat with special reference to subdivision of the nucleus: biotinylated dextran amine study. Brain Res. 1998;797:73–93. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00359-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bowling H, Lopez S, Santini E, Matamales M, Bonito-Oliva A, Hervé D, Hoeffer C, Klann E, Girault JA, Fisone G. Haloperidol regulates the state of phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 via activation of PKA and phosphorylation of DARPP-32. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2561–2570. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Driscoll JR, Wilbrecht L, Margolis EB, Fields HL, Hjelmstad GO. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons target nondopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7811–7816. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1504-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Antunes Rodrigues J, Cunha JM. Effects of cannabidiol in animal models predictive of antipsychotic activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104:260–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02244189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]