Dear Editor,

Human brucellosis is the most common zoonosis worldwide and is caused by gram-negative bacteria, Brucella spp. [1]. Among the Brucella spp., B. abortus, B. canis, B. melitensis, and B. suis can cause human brucellosis. Human brucellosis involves various organs including bone marrow (BM), shows non-specific clinical manifestations including fever, fatigue, back pain, and arthralgia, and can progress to septicemia or multi-organ failure [1,2]. In Korea, since the first case of human brucellosis in 2002 [3], all reported 747 cases have been caused by B. abortus, and the majority were related to the out-break of bovine brucellosis in mid-2000 [4]. We report the first Korean case of human brucellosis caused by B. melitensis.

A 34-yr-old man presented with high fever (39.2℃), significant weight loss (10 kg/month), and back pain that persisted for three weeks. He was a Korean resident living in northwestern China (Yanji, Jilin) who had been working on a stock farm in Pyeongchang, Gangwon Province, Korea for two months before visiting our hospital. He had hepatosplenomegaly, elevated aminotransferases, and pancytopenia. His complete blood count showed the following: hemoglobin, 8.8 g/dL; white blood cells, 2.1×109/L; and platelets, 43×109/L. His BM was normocellular with intact trilineage hematopoiesis, and neither granuloma nor necrosis was present. Plasma cells (CD19+/CD56-) were elevated (11.7%), and polyclonal gammopathy was detected via serum protein electrophoresis. A magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate back pain revealed pyogenic spondylitis at L3-4.

The first two blood cultures yielded gram-negative bacilli, which were identified as B. melitensis by using Vitek 2 (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France). In a microagglutination test (MAT), the antibody titer was 1:80. The patient received doxycycline and rifampicin for three weeks and was discharged with no symptoms except mild leukopenia. The MAT titer was not rechecked during the recovery period, because he declined further treatment.

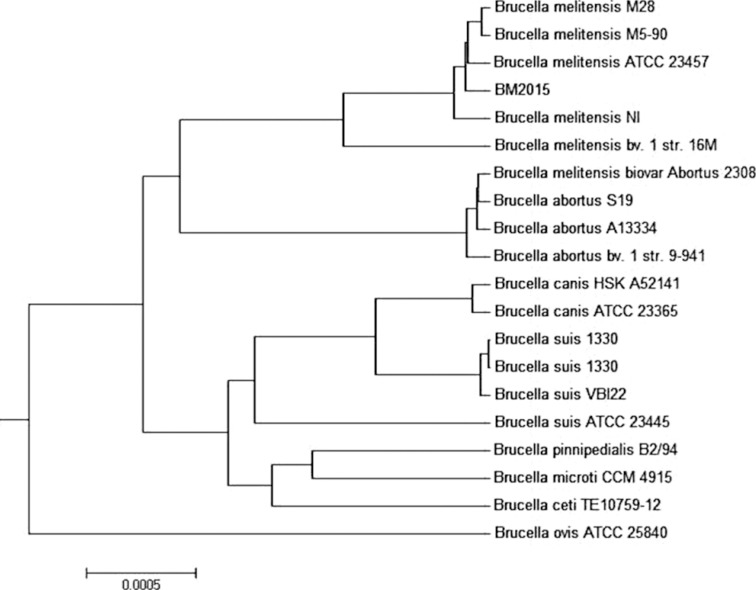

The Vitek 2 system database has a limitation in identifying Brucella spp.: it misidentifies B. abortus as B. melitensis. Therefore, the identification result of B. melitensis was further confirmed at the Division of Zoonoses at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention after the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. After a blood culture, the cultivated product was streaked on both a blood agar plate and a Brucella agar plate and incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO2 atmosphere. After several passages through the Brucella agar plate, the pure culture product (the isolate) tested negative for H2S production and positive for oxidase and urease. DNA was extracted from the isolate to amplify the Brucella-specific genes (16S rRNA, BCSP31, and Omp2) [5]. PCR targeting Omp31, IS711, and BCSS confirmed this isolate as B. melitensis [6,7,8] (Table 1). Draft whole genome sequence analysis assembled by CLC bio CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5.1 (Waltham, MA, USA) revealed that the isolate was B. melitensis (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Primers used in this study and the results of PCR and sequencing.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | Size (specific species) | Reference | Result (PCR and sequencing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16s rRNA | F | TCG AGC GCC CGC AAG GGG | 905 bp (Brucella spp.) | 5 | + |

| R | AAC CAT AGT GTC TCC ACT AA | ||||

| BCSP 31 | F | TGG CTC GGT TGC CAA TAT CAA | 223 bp (B. spp.) | 5 | + |

| R | CGC GCT TGC CTT TCA GGT CTG | ||||

| Omp2 | F | GCG CTA AGG CTG CCG ACG CAA | 193 bp (B. spp.) | 5 | + |

| R | ACC AGC CAT TGC GGT CGG TA | ||||

| Omp31 | F | TGA CAG ACT TTT TCG CCG AA | 720 bp (B. melitensis) | 6 | + |

| R | TAT GGA TTG CAG CAC CGC | ||||

| IS711 | Ba F | GAC GAA CGG AAT TTT TCC AAT CCC | 498 bp (B. abortus) | 7 | - |

| IS711 | TGC CGA TCA CTT AAG GGC CTT CAT | ||||

| Bm F | AAA TCG CGT CCT TGC TGG TCT GA | 731 bp (B. melitensis) | 7 | + | |

| IS711 | TGC CGA TCA CTT AAG GGC CTT CAT | ||||

| Bo F | CGG GTT CTG GCA CCA TCG TCG | 976 bp (B. ovis) | 7 | - | |

| IS711 | TGC CGA TCA CTT AAG GGC CTT CAT | ||||

| Bs F | GCG CGG TTT TCT GAA GGT TCA GG | 285 bp (B. suis) | 7 | - | |

| IS711 | TGC CGA TCA CTT AAG GGC CTT CAT | ||||

| BCSS | F | CCA GAT AGA CCT CTC TGG A | 300 bp (B. canis) | 8 | - |

| R | TGG CCT TTT CTG ATC TGT TCT T |

Fig. 1. Average nucleotide identity tree of Brucella melitensis. The genome tree was constructed by using BM2015 (the isolate) and related Brucella spp.

To identify Brucella spp. when brucellosis is suspected, a careful and complete history should be taken of the patient's occupation, travel, and unpasteurized diet history [9]. The present patient had worked on a sheep farm for two months before admission and experienced nonspecific symptoms (fever, weight loss, and back pain) for three weeks, indicating B. melitensis infection. Before he was in Korea, he had lived in north-western China, where B. melitensis has been dominant [10]. It is not clear whether he had raw food from infected animals in China or in Korea, or whether he acquired brucellosis occupationally by direct skin contact or inhalation of aerosolized infected particles [9]. Although the clinical history appears insufficient, considering that he had been healthy before developing these clinical symptoms, it is unlikely that he already had brucellosis in China.

In the present case, H2S was negative, and oxidase and urease were positive in the biochemical analysis, suggesting the possibility of B. melitensis infection together with the patient's working history on the sheep farm. However, H2S production can be also negative in the other Brucella spp., and molecular identification is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. We used multiple gene targets to detect the Brucella genus using a common PCR assay [5] and also used Omp31, IS711, and BCSS gene targets to distinguish B. melitensis from the other Brucella spp. [6,7,8] (Table 1).

Conclusively, this is the first official case of human brucellosis caused by B. melitensis in Korea that was confirmed by using molecular methods. Careful recording of patient history and molecular identification are necessary in patients with suspected brucellosis to confirm the causative Brucella spp.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Konkuk University and the Korea National Institute of Health (4837-301-210-13, 4838-303-210-13).

We are grateful to Chunlab, Inc., for analyzing and providing an ANI tree from whole genome sequencing of this isolate.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Corbel MJ. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:213–221. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzgan T, Karahocagil MK, Irmak H, Baran AI, Karsen H, Evirgen O, et al. Clinical manifestations and complications in 1028 cases of brucellosis: a retrospective evaluation and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e469–e478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park MS, Woo YS, Lee MJ, Shim SK, Lee HK, Choi YS, et al. The first case of human brucellosis in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2003;35:461–466. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease web statistics system. [accessed on Dec 15, 2015]. http://is.cdc.go.kr/dstat/jsp/stat/stat0001.jsp.

- 5.Yu WL, Nielsen K. Review of detection of Brucella spp. by polymerase chain reaction. Croat Med J. 2010;51:306–313. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2010.51.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta VK, Verma DK, Singh K, Kumari R, Singh SV, Vihan VS. Single-step PCR for detection of Brucella melitensis from tissue and blood of goats. Small Rumin Res. 2006;66:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2660–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang SI, Lee SE, Kim JY, Lee K, Kim JW, Lee HK, et al. A new Brucella canis species-specific PCR assay for the diagnosis of canine brucellosis. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;37:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Versalovic J, Carroll KC, et al., editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2011. pp. 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong Z, Yu S, Wang X, Dong S, Xu J, Wang Y, et al. Human brucellosis in the People's Republic of China during 2005-2010. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e289–e292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]