Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To comprehensively review and critically assess the literature on vaginal estrogen and its alternatives for women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause and to provide clinical practice guidelines.

DATA SOURCES

MEDLINE and Cochrane databases were searched from inception to April 2013. We included randomized controlled trials and prospective comparative studies. Interventions and comparators included all commercially available vaginal estrogen products. Placebo, no treatment, systemic estrogen (all routes), and nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants were included as comparators.

METHODS OF STUDY SELECTION

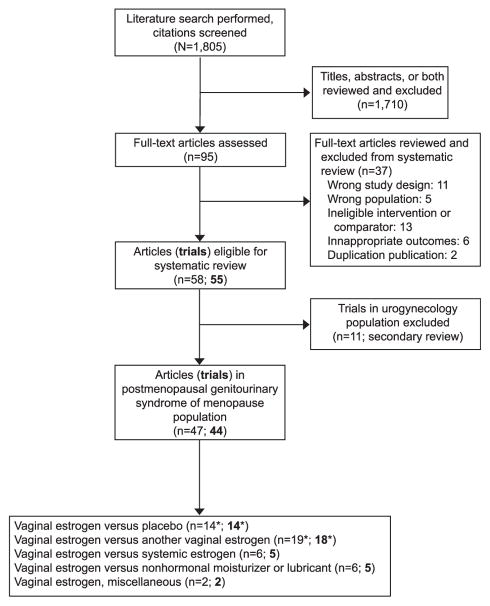

We double-screened 1,805 abstracts, identifying 44 eligible studies. Discrepancies were adjudicated by a third reviewer. Studies were individually and collectively assessed for methodologic quality and strength of evidence.

TABULATION, INTEGRATION, AND RESULTS

Studies were extracted for participant, intervention, comparator, and outcomes data, including patient-reported atrophy symptoms (eg, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, dysuria, urgency, frequency, recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), and urinary incontinence), objective signs of atrophy, urodynamic measures, endometrial effects, serum estradiol changes, and adverse events. Compared with placebo, vaginal estrogens improved dryness, dyspareunia, urinary urgency, frequency, and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Urinary tract infection rates decreased. The various estrogen preparations had similar efficacy and safety; serum estradiol levels remained within postmenopausal norms for all except high-dose conjugated equine estrogen cream. Endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma were extremely rare among those receiving vaginal estrogen. Comparing vaginal estrogen with nonhormonal moisturizers, patients with two or more symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy were substantially more improved using vaginal estrogens, but those with one or minor complaints had similar symptom resolution with either estrogen or nonhormonal moisturizer.

CONCLUSION

All commercially available vaginal estrogens effectively relieve common vulvovaginal atrophy-related complaints and have additional utility in patients with urinary urgency, frequency or nocturia, SUI and UUI, and recurrent UTIs. Nonhormonal moisturizers are a beneficial alternative for those with few or minor atrophy-related symptoms and in patients at risk for estrogen-related neoplasia.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/,CRD42013006656.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause is the constellation of symptoms and signs associated with decreased estrogen levels that can involve the genital system (eg, vaginal or vulvar dryness, burning, dyspareunia) or the lower urinary tract (eg, dysuria, urgency, frequency).1 Prevalence estimates vary, but approximately half of postmenopausal U.S. women report these atrophy-related symptoms, and the negative effect on quality of life is substantial.2–4 Unlike vasomotor symptoms that tend to decrease over time, genitourinary syndrome of menopause will not spontaneously remit and commonly recurs when hormones are withdrawn.3,5

Local vaginal estrogen therapy clearly has utility in treating atrophic vaginitis.5,6 A possible role for local estrogen in the management of lower urinary tract symptoms has also been described.7,8 Unfortunately, among women self-reporting genitourinary syndrome of menopause, only approximately half seek medical attention or are offered help by their health care providers, and fewer than half are satisfied with available guidance or information.4,9 Patient hesitancy to continue use of vaginal estrogens4,10 despite evidence of efficacy underscores a need for an updated comprehensive, systematic review of efficacy and safety of vaginal estrogens and their alternatives in treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause and development of guidelines to assist health care providers and patients with treatment choices. The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) Systematic Group Review aimed to systematically and critically compare efficacy and safety of vaginal estrogens with placebo, each other, systemic estrogen, and nonhormonal vaginal alternatives in the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause with the balance of these benefits and harms used to generate evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

SOURCES

The SGS Systematic Group Review performed a search to identify studies comparing vaginal estrogen application with other interventions aimed at treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause following standard systematic review methodology.11 MEDLINE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched from their inception until April 22, 2013. The search included numerous terms for estrogen products and vulvovaginal and lower urinary tract complaints and was limited to comparative studies (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/A569).

STUDY SELECTION

Participants of interest were postmenopausal women identified as having genitourinary syndrome of menopause.1 All commercially available vaginal estrogen creams, tablets, suppositories, and rings intended for local (not systemic) therapy were allowed as interventions and comparators, including estriol products not U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved but commonly used outside the United States. Placebo, no intervention, systemic estrogen therapy (any route), and vaginal lubricants and moisturizers were also permitted as comparators. The main outcomes of interest were patient-reported subjective symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: vaginal dryness, itching or burning, “most bothersome symptom,” dysuria, urinary urgency, frequency or nocturia, urge and stress urinary incontinence (SUI), and urinary tract infection (UTI). Measures of objective atrophy were also collected: vaginal pH, vaginal maturation index, and examiner-graded signs of atrophy (eg, pallor, petechiae, moisture, elasticity). Urodynamic measures were extracted. Assessments of effects on the endometrium included biopsy results, endometrial thickness by transvaginal ultrasonography, and progesterone challenge testing. Serum estradiol levels were extracted. Adverse events and discontinuation rates and reasons were catalogued.

The titles, abstracts, and full texts (when necessary) were double-screened for eligibility by nine reviewers and discrepancies adjudicated by a third reviewer. Abstract screening was conducted using Abstrackr (http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu/).12 Data extraction was then completed in duplicate by the same nine independent reviewers, all with experience in the systematic review process,13,14 into customized forms in the Systematic Review Data Repository, which is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; it is an open, searchable archive of systematic reviews with data accessible at http://srdr.ahrq.gov.

We assessed the methodologic quality of each study using predefined criteria from a three-category system modified from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.15 Studies were graded as good (A), fair (B), or poor (C) quality based on scientific merit, the likelihood of biases, and the completeness of reporting. The quality of individual outcomes was separately graded within each study. Data from eligible papers were extracted and then grouped by comparator type. For each grouping, an “evidence profile” was generated by grading the quality of evidence for each outcome (eg, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, estradiol level) across studies. We considered methodologic quality, consistency of results across studies, directness of evidence, and other factors such as imprecision or sparseness of evidence to determine an overall quality of evidence in accordance with the Grades for Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation system, which categorizes based on four quality ratings: high, moderate, low, and very low.16

As was described previously,13 we developed guideline statements balancing benefits and harms of the compared interventions while incorporating the overall quality of evidence across all outcomes of interest. All guideline statements were assigned an overall level of strength to the recommendation (1—“strong” or 2—“weak”) based on the quality of the supporting evidence and the size of the net medical benefit. The implications for patients, physicians, and policymakers are detailed in the “Discussion.” The review and guidelines were presented for public comment at the SGS Annual Scientific Meeting in March 2014 and posted on the SGS web site, after which comments were solicited for 4 weeks.

RESULTS

The MEDLINE and Cochrane databases search identified 1,805 citations. Figure 1 outlines the reasons for exclusion of all but 44 studies of interest, which stem from postmenopausal women presenting with genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Fourteen studies (Table 1) compare a vaginal estrogen with placebo17–29 or no treatment30; 18 trials compare it with another vaginal estrogen21,31–48; five trials compare it with an estrogen (by various routes) designed to deliver a systemic dose49–54; and five trials compare vaginal estrogen with nonhormonal moisturizer or lubricant.55–60 The summary of nonplacebo-controlled studies is in Appendix 2 (available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/A569). Two studies fit none of these four categorizations.61,62 Overall study quality was deemed poor in 10 studies, fair in 18, and good in 16 (Table 1) (Appendix 2, http://links.lww.com/AOG/A569). Study arm sample sizes ranged from eight to 828. Study duration was most commonly 12 weeks (24 studies) but ranged up to 52 weeks in six studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study search and systematic review. *One study in two parts has components that are both vaginal estrogen compared with placebo and vaginal estrogen compared with another vaginal estrogen.20

Rahn. Vaginal Estrogen: Review and Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2014.

Table 1.

Studies of Vaginal Estrogen Compared With Placebo in Women With Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause

| Summary of Findings

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Atrophy Measures

|

Objective Atrophy Measures

|

Lower Urinary Tract Atrophy and Infection

|

||||||||||||||||

| Study Author, Country |

Study Quality |

Intervention (n) | Comparator (n) | Follow-Up Duration |

Dryness | Dyspareunia | Itching or Burning |

Vaginal pH |

Vaginal Maturation Indices |

Investigator Scales of Atrophy |

Dysuria | Urgency | Frequency or Nocturia |

UUI | SUI | UTI Frequency |

Overall Adverse Events |

Serum Estradiol |

| Bachmann,17 U.S. | A | Estradiol vaginal tablet 10, 25 micrograms daily for 2 wk, then twice/wk (183) | Placebo tablet, same frequency (47) | 12* and 52 wk | I | I | I | I | I | NS | NS | |||||||

| Bachmann,18 U.S. | A | Conjugated estrogen cream 0.5 g daily for 21 d, then none for 7 d or twice/wk (283) | Placebo cream 0.5 g, same frequency (140) | 12* and 52 wk | NS | I | NS | I | I | I | NS | |||||||

| Cano,19 Spain | B | 50 micrograms estriol gel (1 g) daily for 21 d, then twice/wk (114) | Placebo gel 1 g, same frequency (53) | 12 wk | I | NS | NS | I | I | I | NS | NS | ||||||

| Cardozo,20 U.K. | C | Estradiol vaginal tablet 25 micrograms, frequency not stated (56) | Placebo tablet, same frequency (54) | 12 wk | I | NS | NS | NS | ||||||||||

| Casper,21 Germany | B | Estradiol vaginal ring replaced after 12 wk (33) | Placebo ring; same frequency (34) | 24 wk | NS | I | NS | I | I | I | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| Dessole,22 Italy | B | Estriol 1 mg ovule daily for 2 wk, then 2 mg once/wk (44) | Placebo ovule, same frequency (44) | 24 wk | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | NS | ||||||

| Eriksen,23 Denmark | A | Estradiol vaginal tablet 25 micrograms daily for 2 wk, then twice/wk (81) | Placebo tablet, same frequency (83) | 12 wk | I | I | NS | I | I | I | I | I | NS | |||||

| Eriksen,30 Norway | B | Estradiol vaginal ring replaced every 12 wk (53) | No treatment (55) | 36 wk | I | I | NS | I | I | I | NS | NS | NS | I | I | I | NS | |

| Foidart,24 Belgium | B | Estriol 3.5 mg vaginal suppository twice/wk for 3 wk, then once/wk (56) | Placebo suppository, same frequency (53) | 24 wk | I | I | I | NS | I | I | NS | NS | ||||||

| Freedman,25 U.S. | A | Conjugated estrogen cream 1 g twice/wk (150) | Placebo cream 1 g, same frequency (155) | 12 wk | I | I | I | I | I | NS | ||||||||

| Griesser,26 Germany | A | Estriol 0.2 mg or 0.03 mg ovule daily for 20 d, then twice/wk (142) | Placebo ovule, same frequency (147) | 12 wk | Im | Im | Im | I | I | I | NS | |||||||

| Raz,27 Israel | B | Estriol 0.5 mg cream daily for 2 wk, then twice/wk (50) | Placebo cream, same frequency (43) | 1 and 8 mo | I | I | ||||||||||||

| Simon,28 U.S. | A | Estradiol vaginal tablet 10 micrograms daily for 2 wk, then twice/wk (205) | Placebo tablet, same frequency (104) | 12 and 52 wk | Im | Im | Im | I | I | I | NS | |||||||

| Simunić, 29 Croatia | A | Estradiol vaginal tablet 25 micrograms daily for 2 wk, then twice/wk (828) | Placebo tablet, same frequency (784) | 16 and 52 wk | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | NS | NS | ||

UUI, urgency urinary incontinence; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UTI, urinary tract infection; I, outcome more favorable in Intervention; C, outcome more favorable in Comparator; NS, no significant difference between Intervention and Comparator; Im, most bothersome symptom, which included dryness, dyspareunia, itching, or burning.

Fourteen studies comparing vaginal estrogen with placebo (or no treatment) included 4,232 participants. Overall quality of evidence for this group of studies was fair. Various formulations of vaginal estrogen applied at typical, approved doses consistently demonstrated net benefits. Common genital complaints of vaginal dryness, itching or burning, and dyspareunia all were improved with estrogen use (moderate-quality evidence). Common urinary complaints also were improved using local estrogens: dysuria and urinary urgency (low-quality evidence) and frequency or nocturia (very low-quality evidence). Stress urinary incontinence and UUI also were improved (low-quality and moderate-quality evidence, respectively). Compared with placebo, vaginal estrogen increased maximum urethral closure pressure (low-quality evidence),22 decreased the number of patients with detrusor overactivity (low-quality evidence), and increased maximum cystometric capacity (moderate-quality evidence).29 The frequency of UTI was reduced with use of vaginal estrogen (moderate-quality evidence).

Considering these estrogen-compared with-placebo trials, among patients with an intact uterus, endometrial pathology was rarely encountered during and up to 1 year of use (high-quality evidence); there was one study participant in one trial28 among 205 women (0.5%) followed for 1 year who received 10 micrograms Vagifem (estradiol vaginal tablet) and was diagnosed with endometrial adenocarcinoma stage II, grade 2. However, there were no baseline biopsies in this study. Another trial also following patients for 1 year reported one of 32 (3.1%) patients receiving the estradiol vaginal tablet (25 micrograms) having endometrial hyperplasia (without atypia) on biopsy.17 No other cases of endometrial hyperplasia or more serious pathology were reported in any of the four other studies that sampled the endometrium,18,20,24,25 although two of these followed participants for only 12 weeks20,25 and another for 6 months.24 Collectively, from these six studies, the total reported number of women given vaginal estrogen from which biopsies were obtained was 600, and these yielded the one endometrial cancer diagnosis described previously (0.17%). Because these were trials of various quality and some with very limited duration of follow-up, more precise estimates of endometrial safety cannot be determined. There were no differences in serum estradiol levels in women taking vaginal estrogen compared with placebo (high-quality evidence). Overall, there were no differences in reported adverse events comparing vaginal estrogen with placebo, but these data were variably reported (Table 1).

Eighteen studies comparing one type of vaginal estrogen with another included 2,236 participants. Overall quality of evidence was fair. Five of the trials were designed as equivalence or noninferiority studies.31,32,34,39,41 With few exceptions, no differences were found in efficacy or safety between different vaginal estrogen preparations at typical doses and frequencies. Vaginal dryness, itching or burning, atrophy-related dyspareunia, dysuria, urgency, frequency, nocturia, and SUI and UUI all were improved with available estrogen treatments (moderate-quality evidence). When a 1-mg vaginal estriol ovule was compared with the same medication coupled with pelvic floor muscle therapy, the estrogen-plus-muscle therapy arm had superior improvement in SUI.35 There were insufficient data to comment on whether one formulation of estrogen was superior in reducing frequency of UTIs. Ten studies reported endometrial biopsy findings.31,32,34,38,40,42,44–48 Among patients with an intact uterus (during and up to 1 year of vaginal estrogen use), endometrial pathology was rarely abnormal; this consisted of two cases of hyperplasia with atypia in a study of 165 participants (1.2%) followed for 12 weeks; one received an estradiol vaginal ring and the other estriol cream.34 Differences in serum estradiol levels were not identified between various estrogen delivery mechanisms with the exception of one study comparing the 25-microgram estradiol vaginal tablet to 1.25 mg conjugated estrogen cream daily (ie, 2 g cream daily); a higher percentage of the patients given this conjugated estrogen cream dose had serum estradiol levels above postmenopausal norms.46 However, this dose is higher than that used in today’s general practice.

Five studies, with 226 participants, compared typical vaginal estrogen formulations with an estrogen or estrogen agonist delivered at systemic doses. Overall quality of evidence was poor. The estradiol vaginal ring (which releases 5–10 micrograms estradiol per day) was involved in three studies: one compared with another vaginal estrogen ring delivering 20–30 micrograms estradiol per day52; another study compared with a low-dose transdermal estradiol patch (14 micrograms estradiol per day)51; and the third compared with a higher dose transdermal estradiol patch (50 micrograms per day).49 Long et al compared conjugated estrogen 0.625 mg per day orally with 0.625 mg per day by vaginal cream.53,54 Finally, one study compared conjugated estrogen cream with a synthetic steroid hormone estrogen agonist, tibolone, given orally.50 Similar improvements for both vaginal and systemic therapies were observed for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and urinary complaints of dysuria, urgency, frequency, nocturia, and SUI (very low-quality to low-quality evidence). No data were presented on frequency of UTIs. There was no significant change in endometrial thickness (moderate-quality evidence) or in response to progesterone challenge test (very low quality), and no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer were identified in the one study reporting endometrial pathology at 1 year.49 As expected, serum estradiol levels were elevated more significantly using systemic therapy compared with local estrogen (low-quality evidence).

Five studies compared vaginal estrogen with Replens (nonhormonal moisturizer),55,57–59 hyaluronic acid vaginal tablets,56 or lubricant gel.60 The overall quality of evidence was poor, and 264 participants were involved. Across these studies, vaginal estrogen resulted in greater increases in vaginal maturation, decreased vaginal pH, and improved objective measures of atrophy compared with nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants alone (moderate-quality evidence). The evidence does not suggest a difference between estrogen and moisturizers or lubricants in the improvement of individual atrophy symptoms of vaginal dryness, atrophy-related dyspareunia, itching or burning, and urinary symptoms of dysuria and urgency (low-quality evidence). However, patients with composite symptoms (ie, two or more symptoms) of vulvovaginal atrophy were substantially more improved using vaginal estrogens (low-quality evidence). Data were insufficient to comment on changes in other urinary symptoms, incontinence, urodynamic measures, or UTI frequency. Serum estradiol levels did increase above baseline with vaginal estrogen in a single study,60 but these levels were still within post-menopausal norms. There were no significant differences in endometrial thickness with either type of treatment (two studies reporting)55,60 and no reported cases of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer (one trial in two articles reporting at 12 weeks).58,59

Two studies could not be characterized by the four groupings. Pinkerton et al61 found that the efficacy of the estradiol vaginal ring for treatment of urogenital symptoms was not adversely affected by the addition of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, which acts as an agonist in bone but an antagonist on some genitourinary tissues. The final study was of postmenopausal women with recurrent UTI; participants were randomized to a 0.5-mg vaginal estriol tablet twice weekly and an oral placebo pill or a vaginal placebo tablet and 100 mg oral nitrofurantoin daily.62 In this study, the participants randomized to antibiotic suppression had fewer symptomatic UTI episodes.

DISCUSSION

The SGS Systematic Group Review has developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for use of vaginal estrogen in treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause (Table 2). Each guideline received a “grade” in two parts: strength of recommendation (1 = strong, “we recommend” or 2 = weak, “we suggest”) and overall quality of evidence (high [A] to very low [D]). Most of these recommendations are 2C, meaning low quality of evidence supporting a suggestion that the majority of patients would want to follow but many would not. Physicians must still judge each patient independently and arrive at a management decision consistent with the individual’s preferences. From a policymaking standpoint, there is still room for debate and need for additional evidence. Some guidelines, however, rose to recommendations with moderate quality of evidence (ie, 1B), indicating that because benefits outweigh the risks of treatment, most patients would want and receive the recommended intervention.

Table 2.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause

| Presuming No Contraindication to Vaginal Estrogen, in Postmenopausal Women... | Guideline | Grade | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. with a single urogenital atrophy complaint of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, itching or burning, dysuria, or urinary urgency | we suggest | application of either nonhormonal agents (moisturizers, lubricants) or vaginal estrogen. | 2C |

| 2. with a composite of multiple urogenital atrophy complaints (vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, itching or burning, dysuria, or urinary urgency) | we suggest | application of vaginal estrogen instead of nonhormonal agents. | 2C |

| 3a. presenting with urogenital atrophy complaints (eg, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, itching or burning, dysuria, or urinary urgency) also reporting UUI | we recommend | application of vaginal estrogen (agents studied: estradiol vaginal ring and tablet). | 1B |

| 3b. for those women whose additional urinary complaints are frequency or nocturia or SUI | we suggest | application of vaginal estrogen. | 2C |

| 4a. with urogenital atrophy complaints selecting a vaginal estrogen for treatment | we recommend | application of any commercially available vaginal estrogen at approved doses and frequencies. | 1B |

| 4b. and presuming only genitourinary syndrome of menopause complaints and no other indications for systemic estrogen therapy | we suggest | application of vaginal estrogen instead of systemic therapy. | 2C |

| 4c. the choice of vaginal estrogen (cream, tablet, ovule, suppository, or ring) may be directed by patient preference, ease of application, or cost | Ungraded | ||

| 5. with recurrent UTI with or without urogenital atrophy complaints | we recommend | application of vaginal estrogen (agents studied: estradiol vaginal ring and estriol products). | 1B |

| 6. with a uterus treated with vaginal estrogen | we suggest | clinician vigilance for possible emergence of endometrial pathology—especially in higher risk patients or those with concerning symptoms.* | Ungraded |

| 7. with personal history of breast or endometrial cancer (or at high risk for either) and bothersome genitourinary syndrome of menopause | we suggest | primary application of nonhormonal moisturizer, but one may consider low-dose vaginal estrogen alternatives after informed understanding of potential risks and balancing of individual preferences and needs. | Ungraded |

UUI, urgency urinary incontinence; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UTI, urinary tract infection.

“Grade” provides a level of strength (1—“strong” or 2—“weak”) to the guideline combining quality of the supporting evidence (A—high to D—very low) with size of net medical benefit. See “Discussion.”

Data are insufficient to mandate endometrial surveillance or dictate frequency or means of surveillance.

In this review of studies using vaginal estrogen, there were no cases of either thromboembolism or breast cancer reported, but these data are clearly limited, so the actual risks cannot be commented on directly. Only one study included in this review actually followed women with a personal history of breast cancer.55 Those receiving vaginal estrogen had greater improvement in a composite measure of bothersome atrophy and urinary symptoms than those using a nonhormonal moisturizer, and there were no significant changes in serum estrogen levels. Another study—not included in our review because there was no vaginal estrogen arm—comparing a nonhormonal moisturizer (n = 44) with placebo cream (n = 42) in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors concluded that dryness and dyspareunia were significantly more improved in the moisturizer group as were vaginal pH and the vaginal maturation index.63 Taken together, in postmenopausal women with bothersome genito-urinary syndrome of menopause and a personal history of (or at high risk for) breast cancer, we suggest primary application of a nonhormonal moisturizer, but one may consider low-dose vaginal estrogen alternatives in refractory patients after informed understanding of potential risks and balancing of individual preferences and needs (ungraded). Of the currently available commercial vaginal estrogen products, the estradiol vaginal tablet and ring deliver the smallest weekly doses of estradiol: 20 micrograms and approximately 50 micrograms, respectively. Of note, it is possible that even low-dose estrogen suppositories such as these may interfere with the efficacy of aromatase inhibitors and should, therefore, probably be avoided in those patients being treated with aromatase inhibitors.64 These suggestions align with the 2012 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin for managing gynecologic issues in women with breast cancer.65

There was moderate-quality evidence that UTIs were less frequent with use of vaginal estrogen in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. The few studies including patients with recurrent UTI were relatively small and used different types of estrogen application. When vaginal estrogen was compared directly with antibiotic prophylaxis using oral nitrofurantoin, the antibiotic was superior in prevention of symptomatic recurrent infection.62 Nonetheless, these data are a significant endorsement for vaginal estrogen therapy as a preventive therapy in postmenopausal patients with recurrent cystitis.

The strengths of this review are its robust methodology and the transparent means of evidence-based clinical practice guideline development. There are, however, several limitations. We cannot comment on the relative efficacy or safety of ospemifene, compounded vaginal estrogen products, or herbal or natural alternatives. Clinical practice guidelines are primarily based on moderate overall quality of evidence. Most studies in this review had 12 weeks of follow-up, so it is difficult to comment on longer-term efficacy, risks, and tolerability of vaginal estrogens. Just five of the 18 trials (28%) comparing one vaginal estrogen type with another were powered as noninferiority studies, suggesting a risk of underpowered studies (ie, type II error) in the majority of these trials. Also, there were no universal, validated tools for objective assessment of vulvovaginal atrophy or subjective patient-reported atrophy-related symptoms, and the true effect of genitourinary syndrome of menopause on quality of life was rarely described. Overall, subjective measures of patient bother were too disparate to combine for meta-analyses. Finally, serum estradiol concentrations were determined by radioimmunoassay in eight of 16 studies reporting (50%) with the method of detection unreported in the remainder. Radioimmunoassays have many drawbacks—foremost may be insufficient sensitivity for the very low physiologic serum concentrations of estradiol in postmenopausal women. Thus, there may have been small—but undetectable—elevations of serum estradiol with use of vaginal estrogens (but perhaps still in range of postmenopausal norms); the clinical relevance of such changes is uncertain.66

In conclusion, this systematic review of randomized trials and prospective comparative studies of vaginal estrogen and common alternative therapies confirms the efficacy of all commercially available vaginal estrogens for the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Nonhormonal lubricants may be a useful alternative for patients with mild or few urogenital atrophy complaints and in women at risk for estrogen-responsive neoplasia. Among those patients with more bothersome vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms or urinary complaints of urgency, frequency, nocturia, or SUI and UUI, vaginal estrogen therapy may offer substantial improvement in symptoms. Although these products generally appear safe, a precise estimate of risk to the endometrium with sustained vaginal estrogen use is not clear, and additional long-term study with more consistent assessment of the endometrium and more sensitive assessment for changes in serum estradiol is needed. Finally, further development and use of validated tools for assessing atrophy response to therapy and effect on patient quality of life is needed.

Acknowledgments

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons provided funding support for assistance by methods experts in systematic review and logistic support.

Footnotes

Presented at the 40th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, March 23–26, 2014, Scottsdale, Arizona.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Portman DJ, Gass ML. Vulvovaginal atrophy terminology consensus conference panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: women’s health initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2133–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1790–9. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20:888–902. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a122c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Management of menopausal symptoms. Practice Bulletin No. 141. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202–16. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cody JD, Jacobs ML, Richardson K, Moehrer B, Hextall A. Oestrogen therapy for urinary incontinence in post-menopausal women. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(10):Art. No.: CD001405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001405.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beerepoot MA, Geerlings SE, van Haarst EP, van Charante NM, ter Riet G. Nonantibiotic prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Urol. 2013;190:1981–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon JA, Kokot-Kierepa M, Goldstein J, Nappi RE. Vaginal health in the United States: results from the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes survey. Menopause. 2013;20:1043–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318287342d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulman LP, Portman DJ, Lee WC, Balu S, Joshi AV, Cobden D, et al. A retrospective managed care claims data analysis of medication adherence to vaginal estrogen therapy: implications for clinical practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:569–78. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace BC, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Brodley C, Schmid CH. Semi-automated screening of biomedical citations for systematic reviews. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahn DD, Mamik MM, Sanses TV, Matteson KA, Aschkenazi SO, Washington BB, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in gynecologic surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1111–25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318232a394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, Balk EM, Uhlig K, Lau J, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131–42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898ba9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions–Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches. The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachmann G, Lobo RA, Gut R, Nachtigall L, Notelovitz M. Efficacy of low-dose estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:67–76. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296714.12226.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachmann G, Bouchard C, Hoppe D, Ranganath R, Altomare C, Vieweg A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose regimens of conjugated estrogens cream administered vaginally. Menopause. 2009;16:719–27. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a48c4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cano A, Estévez J, Usandizaga R, Gallo JL, Guinot M, Delgado JL, et al. The therapeutic effect of a new ultra low concentration estriol gel formulation (0. 005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from a pivotal phase III study. Menopause. 2012;19:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182518e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardozo LD, Wise BG, Benness CJ. Vaginal oestradiol for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in postmenopausal women—a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;21:383–5. doi: 10.1080/01443610120059941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casper F, Petri E. Local treatment of urogenital atrophy with an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring: a comparative and a placebo-controlled multicenter study. Vaginal Ring Study Group. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10:171–6. doi: 10.1007/s001920050040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dessole S, Rubattu G, Ambrosini G, Gallo O, Capobianco G, Cherchi PL, et al. Efficacy of low-dose intravaginal estriol on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2004;11:49–56. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000077620.13164.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eriksen PS, Rasmussen H. Low-dose 17 beta-estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;44:137–44. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foidart JM, Vervliet J, Buytaert P. Efficacy of sustained-release vaginal oestriol in alleviating urogenital and systemic climacteric complaints. Maturitas. 1991;13:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(91)90092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman M, Kaunitz AM, Reape KZ, Hait H, Shu H. Twice-weekly synthetic conjugated estrogens vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2009;16:735–41. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318199e734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griesser H, Skonietzki S, Fischer T, Fielder K, Suesskind M. Low dose estriol pessaries for the treatment of vaginal atrophy: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy of pessaries containing 0.2 mg and 0. 03 mg estriol. Maturitas. 2012;71:360–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raz R, Stamm WE. A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:753–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309093291102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon J, Nachtigall L, Gut R, Lang E, Archer DF, Utian W. Effective treatment of vaginal atrophy with an ultra-low-dose estradiol vaginal tablet. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1053–60. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa7c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simunić V, Banović I, Ciglar S, Jeren L, Pavicic Baldani D, Sprem M. Local estrogen treatment in patients with urogenital symptoms. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:187–97. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eriksen B. A randomized, open, parallel-group study on the preventive effect of an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring (Estring) on recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1072–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayton RA, Darling GM, Murkies AL, Farrell EA, Weisberg E, Selinus I, et al. A comparative study of safety and efficacy of continuous low dose oestradiol released from a vaginal ring compared with conjugated equine oestrogen vaginal cream in the treatment of postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann G, Notelovitz M, Nachtigall L, Birgerson L. A comparative study of a low-dose estradiol vaginal ring and conjugated estrogen cream for postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Prim Care Update. 1997;4:109–15. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nachtigall LE. Clinical trial of the estradiol vaginal ring in the U.S. Maturitas. 1995;22(suppl):S43–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00963-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barentsen R, van de Weijer PH, Schram JH. Continuous low dose estradiol released from a vaginal ring versus estriol vaginal cream for urogenital atrophy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;71:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(96)02612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capobianco G, Donolo E, Borghero G, Dessole F, Cherchi PL, Dessole S. Effects of intravaginal estriol and pelvic floor rehabilitation on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chompootaweep S, Nunthapisud P, Trivijitsilp P, Sentrakul P, Dusitsin N. The use of two estrogen preparations (a combined contraceptive pill versus conjugated estrogen cream) intravaginally to treat urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal Thai women: a comparative study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:204–10. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickerson J, Bressler R, Christian CD, Hermann HW. Efficacy of estradiol vaginal cream in postmenopausal women. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;26:502–7. doi: 10.1002/cpt1979264502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dugal R, Hesla K, Sørdal T, Aase KH, Lilleeidet O, Wickstrøm E. Comparison of usefulness of estradiol vaginal tablets and estriol vagitories for treatment of vaginal atrophy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henriksson L, Stjernquist M, Boquist L, Alander U, Selinus I. A comparative multicenter study of the effects of continuous low-dose estradiol released from a new vaginal ring versus estriol vaginal pessaries in postmenopausal women with symptoms and signs of urogenital atrophy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:624–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kicovic PM, Cortes-Prieto J, Milojević S, Haspels AA, Aljinovic A. The treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy with Ovestin vaginal cream or suppositories: clinical, endocrinological and safety aspects. Maturitas. 1980;2:275–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lose G, Englev E. Oestradiol-releasing vaginal ring versus oestriol vaginal pessaries in the treatment of bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms. BJOG. 2000;107:1029–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manonai J, Theppisai U, Suthutvoravut S, Udomsubpayakul U, Chittacharoen A. The effect of estradiol vaginal tablet and conjugated estrogen cream on urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: a comparative study. J Obstet Gyneacol Res. 2001;27:255–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattsson LA, Cullberg G. A clinical evaluation of treatment with estriol vaginal cream versus suppository in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1983;62:397–401. doi: 10.3109/00016348309154209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattsson LA, Cullberg G, Eriksson O, Knutsson F. Vaginal administration of low-dose oestradiol—effects on the endometrium and vaginal cytology. Maturitas. 1989;11:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(89)90213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mettler L, Olsen PG. Long-term treatment of atrophic vaginitis with low-dose oestradiol vaginal tablets. Maturitas. 1991;14:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(91)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rioux JE, Devlin C, Gelfand MM, Steinberg WM, Hepburn DS. 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablet versus conjugated equine estrogen vaginal cream to relieve menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Menopause. 2000;7:156–61. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trevoux R, van der Velden WH, Popovic D. Ovestin vaginal cream and suppositories for the treatment of menopausal vaginal atrophy. Reproduccion. 1982;6:101–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weisberg E, Ayton R, Darling G, Farrell E, Murkies A, O’Neill S, et al. Endometrial and vaginal effects of low-dose estradiol delivered by vaginal ring or vaginal tablet. Climacteric. 2005;8:83–92. doi: 10.1080/13697130500087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antoniou G, Kalogirou D, Karakitsos P, Antoniou D, Kalogirou O, Giannikos L. Transdermal estrogen with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device for climacteric complaints versus estradiol-releasing vaginal ring with a vaginal progesterone suppository: clinical and endometrial responses. Maturitas. 1997;26:103–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)01087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Botsis D, Kassanos D, Kalogirou D, Antoniou G, Vitoratos N, Karakitsos P. Vaginal ultrasound of the endometrium in post-menopausal women with symptoms of urogenital atrophy on low-dose estrogen or tibolone treatment: a comparison. Maturitas. 1997;26:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)01070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta P, Ozel B, Stanczyk FZ, Felix JC, Mishell DR., Jr The effect of transdermal and vaginal estrogen therapy on markers of postmenopausal estrogen status. Menopause. 2008;15:94–7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318148b98b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmgren PA, Lindskog M, von Schoultz B. Vaginal rings for continuous low-dose release of oestradiol in the treatment of urogenital atrophy. Maturitas. 1989;11:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(89)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long CY, Liu CM, Hsu SC, Chen YH, Wu CH, Tsai EM. A randomized comparative study of the effects of oral and topical estrogen therapy on the lower urinary tract of hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long CY, Liu CM, Hsu SC, Wu CH, Wang CL, Tsai EM. A randomized comparative study of the effects of oral and topical estrogen therapy on the vaginal vascularization and sexual function in hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2006;13:737–43. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227401.98933.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biglia N, Peano E, Sgandurra P, Moggio G, Panuccio E, Migliardi M, et al. Low-dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal moisturizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: a preliminary study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:404–12. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ekin M, Yaşar L, Savan K, Temur M, Uhri M, Gencer I, et al. The comparison of hyaluronic acid vaginal tablets with estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:539–43. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nachtigall LE. Comparative study: replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:178–80. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parsons A, Merritt D, Rosen A, Heath H, III, Siddhanti S, Plouffe L, Jr, et al. Effect of raloxifene on the response to conjugated estrogen vaginal cream or nonhormonal moisturizers in postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:346–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kessel B, Nachtigall L, Plouffe L, Siddhanti S, Rosen A, Parsons A. Effect of raloxifene on sexual function in postmen-opausal women. Climacteric. 2003;6:248–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raghunandan C, Agrawal S, Dubey P, Choudhury M, Jain A. A comparative study of the effects of local estrogen with or without local testosterone on vulvovaginal and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1284–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinkerton JV, Shifren JL, La Valleur J, Rosen A, Roesinger M, Siddhanti S. Influence of raloxifene on the efficacy of an estradiol-releasing ring for treating vaginal atrophy in postmen-opausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:45–52. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raz R, Colodner R, Rohana Y, Battino S, Rottensterich E, Wasser I, et al. Effectiveness of estriol-containing vaginal pessaries and nitrofurantoin macrocrystal therapy in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1362–8. doi: 10.1086/374341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee YK, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB. Vaginal pH-balanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:922–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kendall A, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, Smith I. Caution: Vaginal estradiol appears to be contraindicated in postmenopausal women on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:584–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Management of gynecologic issues in women with breast cancer. Practice Bulletin No. 126. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:666–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824e12ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson RE, Grebe SK, DJOK, Singh RJ. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of estradiol and estrone in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2004;50:373–84. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]