Highlights

-

•

We treated a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism caused by parathyroid adenoma.

-

•

Parathyroid carcinomas are rare malignant cases of primary hyperparathyroidism.

-

•

The case of a large parathyroid adenoma with osteitis fibrosa cystica is rare.

-

•

Differentiation of benign and malignant parathyroid tumors is sometimes difficult.

Keywords: Hyperparathyroidism, Parathyroid adenoma, Ectopic parathyroid tumor, Osteitis fibrosa cystica

Abstract

Introduction

Parathyroid adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism. However, cases of parathyroid adenomas greater than 4 cm with osteitis fibrosa cystica are extremely rare. Herein, we report a case of resection of a large ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma.

Case presentations

A 46-year-old female with chief complaints of bone pain and gait disturbance was referred to our hospital. Physical examination revealed many mobile teeth in her oral cavity, distortion of the vertebral body, and bowlegs. Laboratory tests showed hypercalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and elevated serum levels of intact parathyroid hormone. Chest CT revealed a 42-mm well–defined, enhancing mass in front of the left-sided tracheal bifurcation. Her findings were diagnosed as primary hyperparathyroidism due to an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid tumor. We performed a median sternotomy and resected the tumor. The tumor was a solid, yellowish-brown mass measuring 42 × 42 mm. Pathologically, the tumor consisted mainly of chief cells with some oxyphil cells; there were no necrotic areas or nuclear atypia, and few mitotic figures. We diagnosed the tumor as an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma. Eight months after the resection, her serum calcium, phosphorus, and intact PTH levels were normal.

Discussion and conclusions

Parathyroid adenomas and parathyroid carcinomas have disparate natural histories, but they can be difficult to differentiate on the basis of preoperative clinical characteristics. We believe that long-term follow-up of these cases is required because there have been few reports on the postoperative natural history of large parathyroid adenomas.

1. Introduction

Differentiation of benign and malignant parathyroid tumors is sometimes difficult. In fact, because parathyroid carcinomas have a very low incidence rate, no staging system has been established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Generally, diagnoses of parathyroid adenoma and parathyroid carcinoma are made on the basis of both the clinical findings and the histological criteria as proposed by Schantz and Castleman [1]. Herein, we report our experience with a case of a large ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma with osteitis fibrosa cystica, which was diagnosed as a parathyroid adenoma based on the pathological findings, despite parathyroid carcinoma being initially suspected due to preoperative clinical findings.

2. Presentation of case

A 46-year-old female with complaints of bone pain, gait disturbance, and a feeling of weakness was referred to the Division of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery of our hospital for evaluation of an abnormal shadow on a chest computed tomography (CT). Her past medical history was significant only for a thoracic wall deformity which had developed 4 years earlier. Physical examination revealed many mobile teeth in her oral cavity; distortion of the vertebral body; and bowlegs, which are associated with the features of osteitis fibrosa cystica; but no presence of palpable mass on her neck.

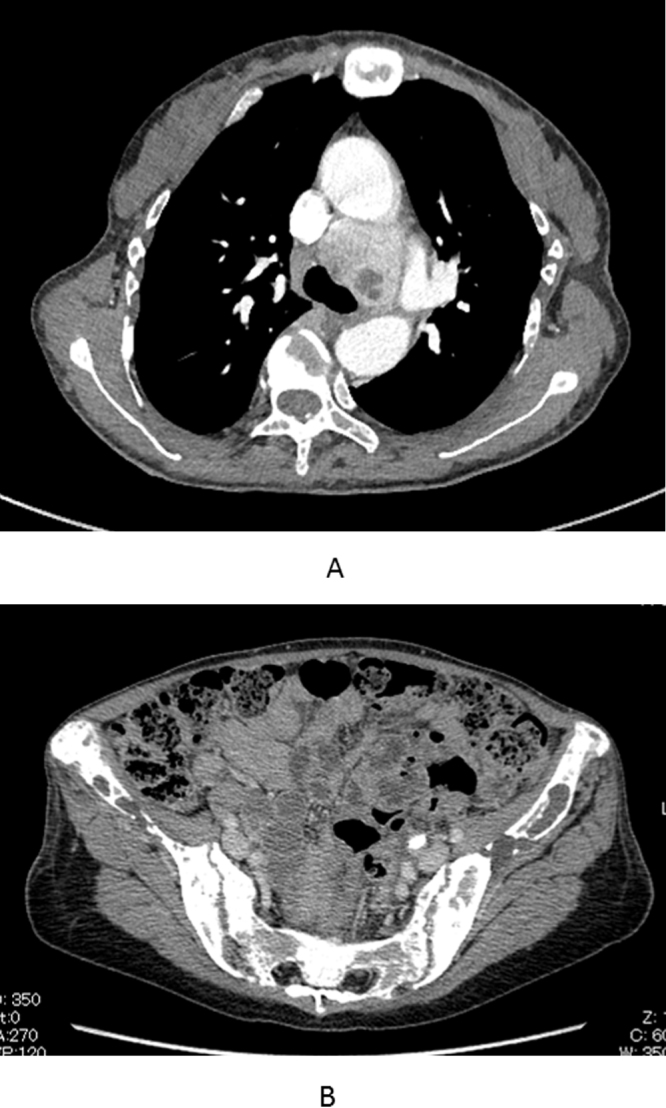

Laboratory tests showed slight anemia (10.4 g/dL; normal range, 11.5–14.0 g/dL); elevated alkaline phosphatase level (7617 IU/L; normal range, 120–325 IU/L); hypercalcemia (15.8 mg/dL; normal range, 8.7–11.0 mg/dL); hypophosphatemia (2.2 mg/dL; normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL); elevated serum levels of intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) (2560 pg/mL; normal range, 10–65 pg/mL); and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (82.9 pg/mL; normal range, 20–60 pg/mL). On pulmonary function testing, vital capacity (VC) and percent VC were 2160 mL and 79.0%, respectively. A chest X-ray revealed a remarkable thoracic wall deformity (Fig. 1A, B), but no tumor was identified. A CT scan revealed a 42-mm, well-defined, enhancing mass, including a partial low-density area in front of the left-sided tracheal bifurcation (Fig. 2A), and extremely low bone mineral density (Fig. 2B). 99m Tc-methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile (MIBI) scintigraphy showed an accumulation in the mediastinum in both the early and the late phases. We then diagnosed her findings as primary hyperparathyroidism due to an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid tumor.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray revealing a remarkable thoracic wall deformity on the frontal (A) and lateral view (B).

Fig. 2.

CT scan revealing a 42 mm, well-defined, enhancing mass, including a partial low-density area in front of the left-sided tracheal bifurcation.

(A) The iliac bone mineral density is extremely low.

On clinical examination, because a malignant tumor could not be ruled out, we scheduled the patient for a resection of the mediastinal ectopic parathyroid tumor, including the surrounding lymph nodes. We performed a median sternotomy and a pericardial incision. After dissection between the superior vena cava and the ascending aorta, we made an incision in the pericardium behind these vessels and exposed the ectopic parathyroid tumor. We were able to bluntly resect the tumor from the proximal right pulmonary artery and left main bronchus. Macroscopically, the tumor was a solid, yellowish-brown mass measuring 42 × 42 mm, with partial foci of hemorrhage. The entire specimen seemed to be enclosed by a thin, fibrous, capsule-like structure and by adipose tissue. The tumor was well-circumscribed, but there was no capsule and few small nodules in the surrounding adipose tissue (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

The tumor is well-circumscribed, but there are no capsules and only a few small nodules (arrow) in the surrounding adipose tissue (hematoxylin and eosin, ×5). (A) Tumor cells consisting mainly of chief cells and some oxyphil cells. No necrotic areas or nuclear atypia present and only a few mitotic figures (hematoxylin and eosin, ×200).

On pathological examination, the tumor consisted mainly of chief cells and some oxyphil cells (Fig. 3B). There were no necrotic areas or nuclear atypia, and few mitotic figures. Ki67 immunostaining was generally positive in about 1% of the tumor. There was no blood vessel invasion on Elastica Van Gieson staining, and no lymphatic involvement on D2-40 staining. A small rim of normal tissue was existed. From the above histopathological results, the tumor was diagnosed as an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma.

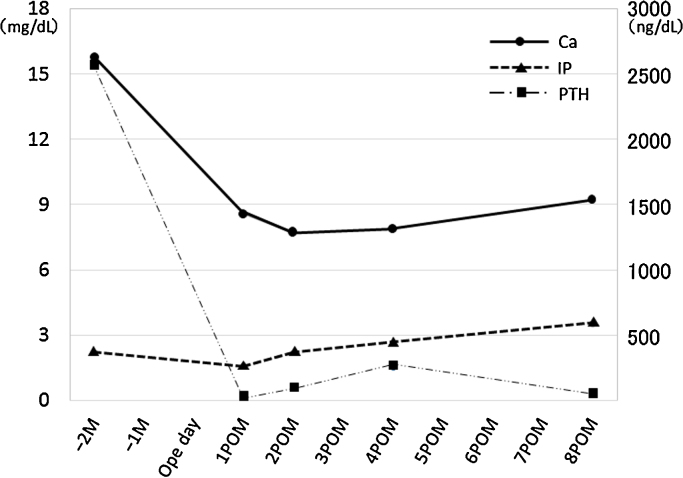

Postoperatively, we had great difficulty treating her persistent hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia (so-called “hungry bone syndrome”) [2]. After rehabilitation, which mainly comprised gait training, she was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 65, ambulating with an independent gait. Eight months after the resection, her serum calcium, phosphorus, and intact PTH levels were normal (9.2 mg/dL, 3.5 mg/dL, and 47 pg/mL, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Timeline of serum calcium, phosphorus, and intact PTH levels.

3. Discussion

In this case, we treated a female patient with primary hyperparathyroidism caused by an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid tumor. Most ectopic parathyroid glands are found in close approximation to the thymus gland. The inferior parathyroid glands originate from the third branchial pouch and hence are usually in close proximity to the thymus, bronchus, aortic arch, esophagus, and heart. Ectopic parathyroid tumors account for 1% to 16% of surgical cases of primary hyperparathyroidism [3,4]. The mediastinum is the most common location for ectopic parathyroid tumors, with approximately 20% of parathyroid tumors located in this area. [5]. Similarly, in a large review of ectopic parathyroid tumors by Masatsugu et al., 5 of 19 cases (26%) had tumors in the mediastinal space [3].

Parathyroid tumors are classified as adenomas and carcinomas. Parathyroid adenomas are benign tumors that account for 85% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism [6]. In contrast, parathyroid carcinomas are rare malignancies that account for about 2% of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism. Parathyroid adenomas and parathyroid carcinomas have disparate natural histories, but they can be difficult to differentiate on the basis of preoperative clinical characteristics. Although a diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma cannot be made on the preoperative clinical appraisal, the clinical characteristics, such as hypercalcemia, high levels of parathyroid hormone, and osteitis fibrosa cystica (a skeletal disease related to long-lasting, end-stage hyperparathyroidism) have been well documented [6], [7], [8], [9]. Table 1 shows the clinical features of parathyroid carcinomas as reported in 6 studies [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], and their prevalence was contrasted with that of benign counterparts.

Table 1.

Reports on the clinical features of parathyroid carcinoma.

| Author | Population (n) | Clinical feature | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levine et al. [10] | Carcinoma (10) | Ca ≥ 14 mg/dl | 0.80 (0.35–0.93) | 0.61 (0.32–0.86) |

| Atypical adenoma (8) | PTH > × 2 ULNR | 0.80 (0.28–0.99) | 0.42 (0.15–0.72) | |

| Adenoma (13) | Osteitis fibrosa cystica | 0.50 (0.19–0.81) | 0.38 (0.14–0.68) | |

| Palpable neck mass | 0.50 (0.07–0.93) | 1.00 (0.75–1.00) | ||

| Obara et al. [11] | Carcinoma (7) | Osteitis fibrosa cystica | 0.43 (0.10–0.82) | 0.94 (0.85–0.99) |

| Adenoma (58) | ||||

| Stojadinovic et al. [12] | Carcinoma (20) | Palpable neck mass | 0.80 (0.56–0.94) | 1.00 (0.92–1.00) |

| Atypical adenoma (8) | ||||

| Adenoma (45) | ||||

| Lumachi et al. [13] | Carcinoma (15) | Ca ≥ 3.0 mmol/l | 0.73 (0.45–0.92) | 0.60 (0.32–0.84) |

| Adenoma (15) | ||||

| Robert et al. [14] | Carcinoma (9) | Ca ≥ 3.27 mmol/l | 0.56 (0.21–0.86) | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) |

| Adenoma (302) | PTH ≥ × 4 ULNR | 1.00 (0.66–1.00) | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | |

| Tumor weight ≥ 1.9 g | 1.00 (0.66–1.00) | 0.81 (0.76–0.85) | ||

| Okamoto et al. [15] | Carcinoma (12) | Palpable neck mass | 0.92 (0.62–0.99) | 0.82 (0.76–0.88) |

| Adenoma (180) | Ca ≥ 12 mg/dl | 0.83 (0.52–0.98) | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) | |

| C-PTH ≥ × 10 ULNR | 0.42 (0.15–0.72) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | ||

| Osteitis fibrosa cystica | 0.58 (0.28–0.85) | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) |

Numbers in parentheses represent the 95% confidence interval.

Ca; serum caicium, PTH; serum parathyroid hormone, ULNR; upper limit of normal range.

In our case, the patient’s levels of serum calcium and PTH were extremely high. She also had chief complaints of bone pain and gait disturbance, which are features of osteitis fibrosa cystica, but she did not have a palpable neck mass. In regard to tumor size, Lumachi et al. reported that the mean size of resected parathyroid tumors was significantly higher in patients with carcinomas than in those with adenomas [13]. Stojadinovic et al. reported that in 53 patients with parathyroid adenomas, including atypical adenomas, the tumor size was 3.5 cm or less [12]; thus, as we previously mentioned, we suspected preoperatively that the tumor might be a parathyroid carcinoma.

The histopathological criteria for parathyroid carcinomas as defined by Schantz and Castleman include (1) thick fibrous bands, (2) mitotic activity, (3) trabecular growth pattern, and (4) capsular, vascular, and adjacent soft-tissue invasion [1]. However, morphological features, such as fibrous bands, mitotic activity, and trabecular growth, have been identified in parathyroid adenomas as well [1,16]. In our case, the tumor did not have an obvious capsular structure, and there were a few small nodules around the adipose tissue. However, because there were no necrotic areas, nuclear atypia, blood vessel invasion, or lymphatic involvement, and few mitotic figures; the tumor was diagnosed as an ectopic parathyroid adenoma. Although there was no definitive pathological evidence of a malignant tumor, we could not rule this out. We postulated that there were two reasons why the adenoma was so large. First, it took a long period of 4 years prior to the start of therapy until the symptoms appeared. Second, in contrast to a tumor in a cervical site, the enlargement of the parathyroid tumor may have been facilitated by the negative intrathoracic pressure and the large potential space in the mediastinum.

4. Conclusion

We had difficulty distinguishing a parathyroid adenoma from a parathyroid carcinoma preoperatively. There have been few reports on the postoperative natural history of large parathyroid adenomas. To our knowledge, there has been only 1 reported case of a large parathyroid adenoma greater than 4 cm with osteitis fibrosa cystica [17]. Consequently, we believe that long-term follow-up of these cases is required.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author contribution

Seijiro Sato wrote the draft of the article. Akihiko Kitahara, Terumoto Koike, and Takehisa Hashimoto made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study or to the acquisition of data. Riuko Ohashi and Noriko Motoi had been involved in the diagnostic pathology. Masanori Tsuchida was involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version to be submitted.

Guarantor

Seijiro Sato.

References

- 1.Schantz Z., Castleman B. Parathyroid carcinoma: a study of 70 cases. Cancer. 1973;31(3):600–605. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<600::aid-cncr2820310316>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright F., Reifenstein E.C., Jr. Baltimore; William and Wilkins: 1948. The Parathyroid Glands and Metabolic Bone Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masatsugu T., Yamashita H., Murakami T., Watanabe S., Uchino S., Yamashita H. Primary hyperparathyroidism caused by ectopic parathyroid tumor. J. Jpn. Surg. Assoc. 2002;63(10):2353–2357. (abstract in English) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy P., Christopher R.M. Incidence and location of ectopic abnormal parathyroid glands. Am. J. Surg. 2006;191(3):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortson J.K., Patel V.G., Henderson V.J. Parathyroid cysts: a case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(10):1726–1728. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koea J.B., Shaw J.H. Parathyroid cancer: biology and management. Surg. Oncol. 1999;8(3):155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shane E. Clinical review 122: parathyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86(2):485–493. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimoto Y., Obara T. How to recognize and treat parathyroid carcinoma. Surg. Clin. North Am. 1987;67(2):343–357. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obara T., Okamoto T., Kanbe M., Iihara M. Functioning parathyroid carcinoma: clinicopathologic features and rational treatment. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1997;13(2):134–141. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199703/04)13:2<134::aid-ssu9>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin K.E., Galante M., Clark O.H. Parathyroid carcinoma versus parathyroid adenoma in patients with profound hypercalcemia. Surgery. 1987;101(6):649–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obara T., Fujimoto Y., Kanaji Y., Okamoto T., Hirayama A., Ito Y. Flow cytometric DNA analysis of parathyroid tumors: implication of aneuploidy for pathologic and biologic classification. Cancer. 1990;66(7):1555–1562. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1555::aid-cncr2820660721>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stojadinovic A., Hoos A., Nissan A., Dudas M.E., Cordon-Cardo C., Shaha A.R. Parathyroid neoplasms: clinical, histopathological, and tissue microarray-based molecular analysis. Hum. Pathol. 2003;34(1):54–64. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumachi F., Ermani M., Marino F., Poletti A., Basso S.M., Iacobone M. Relationship of AgNOR counts and nuclear DNA content to survival in patients with parathyroid carcinoma. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2004;11(3):563–569. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert J.H., Trombetti A., Garcia A., Pache J.C., Herrmann F., Spiliopoulos A. Primary hyperparathyroidism: can parathyroid carcinoma be anticipated on clinical and biochemical grounds? Report of nine cases and review of the literature. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2005;12(7):526–532. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamoto T., Obara T., Fujimoto Y., Izuo M., Ito Y., Kanaji Y. Preoperative diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma: quantitative analysis of preoperative information. Endocr. Surg. 1991;8(4):401–405. (abstract in English) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghandur-Mnaymneh L., Kimura N. The parathyroid adenoma: a histopathologic definition with a study of 172 cases of primary hyperparathyroidism. Am. J. Pathol. 1984;115(1):70–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L., Chen L., Yang Y., Han J., Wu S., Bao Y. Giant anterior mediastinal parathyroid adenoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2012;37(9):889–891. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31825ae8b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]