Highlights

-

•

Eccrine Porocarcinoma (EPC) is rare. It seldom occurs in the early 20s, or arises in the abdominal wall

-

•

EPC is easily misdiagnosed due to lack of specific morphological features. Clinical picture usually consists of a painless nodule or papule

-

•

Definitive diagnosis is achieved by histopathological examination

-

•

Early definitive surgical excision with wide tumor free margins leads excellent results. Risk of local recurrence is about 20%

-

•

High index of suspicion for EPC should be maintained in patients with cystic abdominal wall masses, especially in case of ulceration or discharge

Keywords: Eccrine porocarcinoma, Poroma, Sweat gland, Carcinoma, Abdominal wall, Mass

Abstract

Introduction

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare malignancy of eccrine sweat glands. It is often seen during the sixth to eighth decades of life. We report the first case of eccrine porocarcinoma arising on the abdomen of a 21-year-old patient with ulcerative colitis.

Case presentation

A 21-Year-old female presented to emergency department with a one month history of an enlarging mass over left lower abdomen. Abdominal examination revealed a slightly erythematous, nodular and non-mobile firm mass in left lower quadrant. There was superficial ulceration with slight serous discharge. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a superficial cystic lesion over the anterior abdominal wall, provisionally diagnosed as sebaceous cyst. Incision and drainage were performed and on follow-up, no signs of healing were observed and the patient subsequently underwent surgical excision. Histopathological examination revealed an eccrine porocarcinoma.

Discussion

EPC is a rare and aggressive tumor. It may occur de novo or as a result of malignant transformation of an eccrine poroma. A long period of clinical history is often encountered. It usually occurs on the lower extremities followed by the, trunk, head and neck, and upper extremities. The clinical picture usually consists of a painless nodule or papule. Treatment is wide local excision. No strong evidence exists for adjuvant therapy. The risk of local recurrence is about 20%.

Conclusion

High index of suspicion is required for diagnosis of EPC. Early diagnosis is achieved by histopathological examination and early definitive surgical excision leads to excellent results.

1. Introduction

Eccrine Porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare and aggressive tumor with an incidence of 0.005% to 0.01% of all epithelial cutaneous tumors [1]. It carries high risk of local recurrence, regional lymph node invasion, and distant metastasis. It is often seen during the sixth to eighth decade of life, and most commonly affects the lower extremities [1]. To the best of our knowledge, this case represents the first report of EPC arising on the abdomen of a patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) and in the early 20′s.

2. Case presentation

A 21-Year-old African American female presented to the emergency department (ED) with a one month history of an enlarging mass over left lower abdomen. The mass was first noticed approximately one month prior to presentation. There was no history of pain, fever, malaise, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bloody diarrhoea, or abdominal distension. Past medical history included UC diagnosed nine months ago. Drug history included mesalamine and prednisolone. Menstrual, surgical and family history were non-contributory.

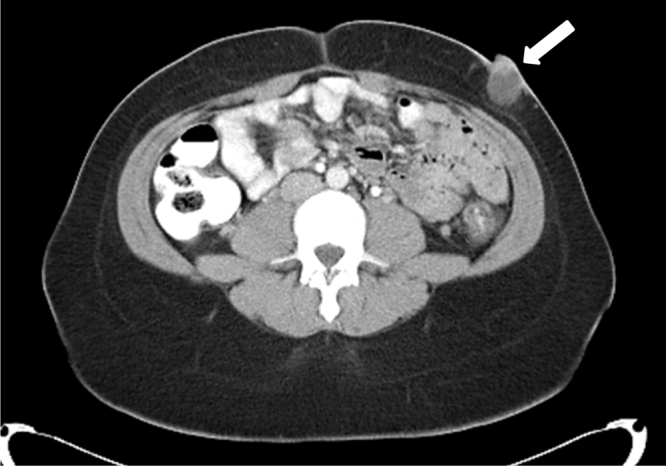

On examination, vital signs were normal. Abdominal examination revealed a non-distended, non-tender abdomen with a 3 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm, slightly erythematous, nodular, firm and non-mobile mass in left lower quadrant, with superficial ulceration and slight serous discharge. Laboratory investigations were non-contributory. Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a 3.2 cm × 2.4 cm × 2.3 cm superficial cystic lesion over the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Upon chart review, we noticed the mass present on a CT obtained four months ago, howevr, was overlooked at the time. The patient was provisionally diagnosed with a questionable sebaceous cyst. Incision & drainage were performed yielding moderate serosanguinous exudate. The wound was left open to heal, and the patient was discharged on a course of antibiotics.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of abdomen with contrast (axial view) showing an abdominal wall mass 3.2 cm x 2.4 cm x 2.3 cm (white arrow).

Fig. 2.

CT scan of abdomen (sagittal view) showing anterior abdominal wall mass (white arrow).

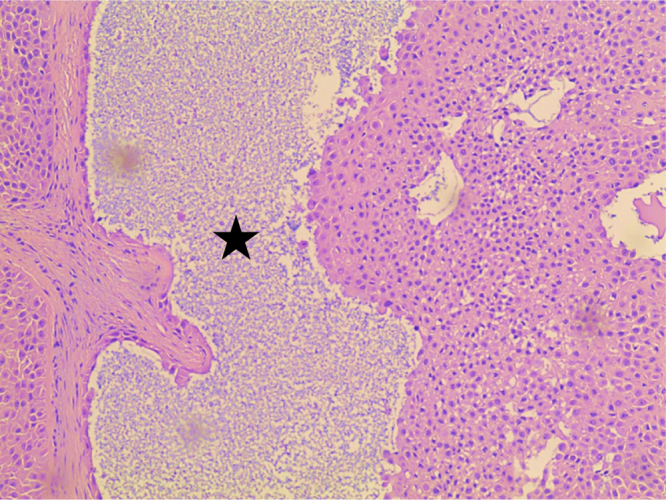

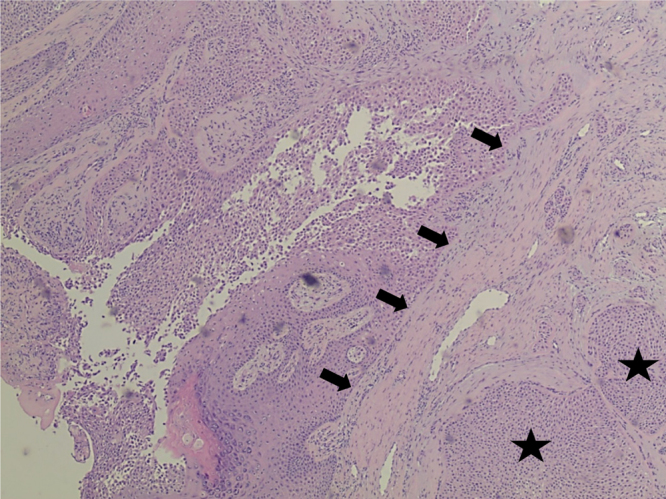

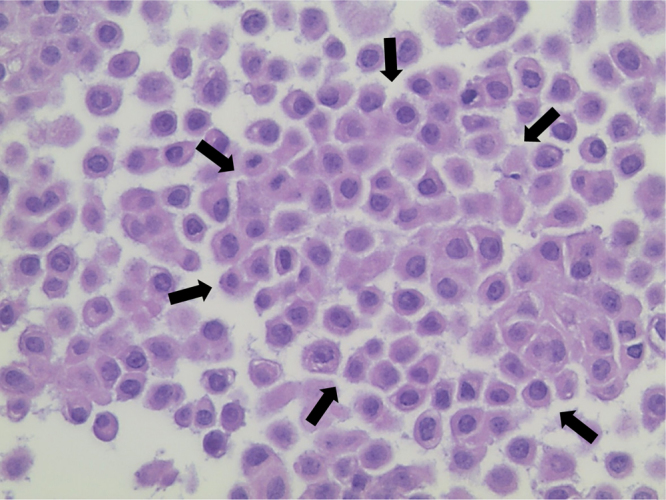

A week later on follow up, no signs of healing were evident and the patient complained of a continuously discharging wound. Consequently, she underwent surgical excision with primary wound closure. Histopathological examination of the excised tissue revealed a poroid neoplasm originating from the overlying epidermis and extending in lobules into the deep dermis to the level of the dermal-subcutaneous junction (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 ). Immunohistochemical staining revealed tumor cells strongly positive for cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin p63, with focal immunoreactivity for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). A final diagnosis of completely excised EPC with free but narrow margins was concluded. Follow-up CT scans of the chest, and abdomen & pelvis with contrast revealed no signs of metastasis. Two weeks later, the patient underwent surgical re-excision with primary wound closure to ensure wider safety margins, and was discharged the same day. Follow-up MRI of the abdomen was within normal. Histopathological examination results after re-excision revealed tumor free margins. The patient continued to follow-up for five months and did well, after which she was lost to follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Cystic space formation (black star) in eccrine porocarcinoma (100 × magnification, H&E stain).

Fig. 4.

Initial biopsy showing desmoplastic response (black arrows) and Islands of tumor cells (black stars) in eccrine porocarcinoma (40× magnification, H&E stain).

Fig. 5.

Cohesive response of poroid cells in eccrine porocarcinoma (demarcated by black arrows, 400× magnification, H&E stain).

3. Discussion

EPC is a rare malignancy of the intra-epidermal ductal portion of eccrine sweat glands. The term ‘eccrine porocarcinoma’ was first described in 1969 by Mishima and Morika [2]. The exact etiology of EPC is unclear. It may occur de novo or as a result of malignant transformation of long standing benign eccrine poroma. Expression of p53 protein may have a role in the carcinogenesis of EPC [3]. The time to malignant transformation of a benign poroma is highly variable and can range from months to decades. A long period of clinical history is often encountered (up to 50 years), but rapid development within few months has also been reported [1].

EPC is most commonly seen in adults between 50 and 80 years of age with some predominance in the female gender [1], [4]. It has also been reported in children and young adults, the youngest being an 8-year-old girl [5]. To date, we found only eight cases of EPC reported in patients aged 25 years or younger [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. EPC usually arises on the lower extremities (44%), followed by the trunk (24%), head & neck (23%), upper extremities (11%), and rarely involves other areas [1]. To date, we found only seven cases of EPC that have been reported to arise on the abdomen, and all cases were greater than 60-years of age [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. To the best of our knowledge, this case represents the first report of EPC arising on the abdomen of a patient with UC and in the early 20s.

It is contended that similar to other neoplasms, the risk of EPC is higher in patients who are immunosuppressed as a result of disease or therapy [6]. Upon literature review, we did not encounter any reports of EPC that occurred in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The base line risk for extra-intestinal solid tumors in patients with IBD independent of therapy is less clear [17]. Additionally, there have been very few reports on the development of multiple eccrine poromas in immunosuppressed patients [18]. On the other hand, Mahomed et al. suggested a possible role for ultraviolet radiation and chronic immunosuppression in the induction of malignant squamous differentiation in a subset of patients with EPCs [6]. However, in our case, the patient received corticosteroid therapy for only one month prior to presentation. Although tempting, it is difficult to postulate that the patient was indeed at a higher risk for development of a poroma or EPC due to UC or associated immunosuppression from therapy. However, one might hypothesize that an association between UC and the development of EPC may possibly exist, but yet to be proven.

The clinical picture of EPC usually consists of a painless nodule or papule that increases in size over years to decades and may ulcerate or bleed upon trauma [1]. The tumor size is variable and ranges from <1 cm to 10 cm. Multinodularity, ulceration and rapid growth may be associated with either local recurrence or metastasis [1]. Diagnosis of EPC is mainly dependent on biopsy and histopathological examination with demonstration of either an invasive architectural pattern, and/or cytological pleomorphism with eccrine differentiation. Cohesive basaloid squamous epithelial cells are most commonly seen, however, other cell types including spindle, clear, and mucin producing cells, or melanocytes may be present [1]. Cellular atypia may also be observed and is not necessarily suggestive of malignancy as it may be similarly observed in benign eccrine poroma. [1] Local or diffuse clear cell changes may occur due to the glycogen content of tumor cells and may be identified by positive staining with Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) [1], [4].

Differential diagnosis of EPC is wide and includes benign and malignant neoplasms of the skin, viscera, eccrine and apocrine glands. Histologically, ductal differentiation of poromatous epithelial cells is the hallmark of diagnosis. Due to simultaneous epidermoid differentiation, diagnosis of EPC may be confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), EMA, and p53 protein [1], [3]. It has been demonstrated that EMA has higher positivity than CEA [4]. Positive staining for CEA and/or EMA highlights ductal differentiation and intracytoplasmic lumina. However, luminal structure disappears in recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions, rendering immunohistochemical staining for CEA and EMA less useful. The use of immunostaining for S-100 protein may be the definite evidence for diagnosis of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated EPC [19].

Tumor thickness tends to be the main prognostic factor for EPC. Sentinel node biopsy has been useful for detecting micro-metastasis to regional lymph nodes [1]. Tumors that are more than 7mms in thickness, and more than 14 mitoses per high power field with lymph vascular space invasion tend to carry poor prognosis [1], [6].

Treatment often involves wide local excision with lymphadenectomy if regional lymph nodes were involved. Due to high rate of local recurrence, wide excision of the primary tumor with histologically clear margins is mandatory. Proper surgical resection leads to a curative outcome in 70–80% of cases. The risk of local recurrence of EPC is about 20% [11]. Metastasis may occur either locally to regional lymph nodes or distantly, in about 20% and 11% of cases respectively. The tumor tends to spread tangentially in the lower third of the epidermis, then later infiltrates the dermis, subcuticular fat and lymphatic system. Patients with EPC and lymph node metastasis have an estimated mortality rate of 67% [1]. Attempts using Mohs micrographic surgery have been reported to reduce morbidity and local recurrence [20]. There is no strong evidence or data available on the use of adjuvant therapy including chemotherapy and radiotherapy for metastatic tumors [11].

4. Conclusion

EPC is a rarely encountered tumor that poses a diagnostic challenge due to the lack of specific etiological factors and morphological characteristics. No standard protocols or guidelines are available for its diagnosis and management. High index of suspicion should be maintained, and EPC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with superficial, cystic abdominal wall masses, especially in the presence of ulceration or serous discharge. Early diagnosis achieved by histopathological examination in addition to early definitive surgical excision leads to excellent results.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding sources

Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

Hurley Medical Center Scientific Review Committee was contacted and verified that IRB approval was not required for this case report.

Consent

Exhaustive attempts have been made to contact the family and have been unsuccessful. A letter signed by the Trauma Services Department director taking responsibility to publish this article is included with this submission with description of attempts made to contact the family. The article has been sufficiently anonymized not to cause harm to the patient or their family.

Author contribution

All authors were involved in the preparation of this manuscript. Narendrasinh Parmar designed and performed all aspects of the operation. Mohamed Mohamed, and Adel Elmoghrabi assisted in data collection, drafting and revising the manuscript. Michael McCann made substantial edits and revisions to the drafted manuscript. Mohamed A Mohamed Michael McCann contributed to the design and provided overall supervision of the paper.

All authors read and approved the final article.

Guarantor

Narendrasinh Parmar, Mohamed Mohamed, Adel Elmoghrabi and Michael McCann.

References

- 1.Robson A., Greene J., Ansari N., Kim B., Seed P.T., McKee P.H., Calonje E. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001;25(6):710–720. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002. Jun 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishima Y., Morioka S. Oncogenic differentiation of the intraepidermal eccrine sweat duct: eccrine poroma, poroepithelioma and porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1969;138(4):238–250. doi: 10.1159/000253989. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akalin T., Sen S., Yücetürk A., Kandiloglu G. P53 protein expression in eccrine poroma and porocarcinoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2001;23(5):402–406. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00003. Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riera‐Leal L., Guevara‐Gutiérrez E., Barrientos‐García J.G., Madrigal‐Kasem R., Briseño‐Rodríguez G., Tlacuilo‐Parra A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: epidemiologic and histopathologic characteristics. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015;54(5):580–586. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12714. May 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valverde K., Senger C., Ngan B.Y., Chan H.S. Eccrine porocarcinoma in a child that evolved rapidly from an eccrine poroma. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2001;37(4):412–414. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1221. Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahomed F., Blok J., Grayson W. The squamous variant of eccrine porocarcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008;61(3):361–365. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049213. Mar 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon H., Smart C. An unusual case of porocarcinoma arising on the scalp of a 22-Year-old woman. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2015;37(3):237–239. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000111. Mar 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins B., Urquhart A.C., Holt J.J. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the external ear. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90(August (8)):E25–E27. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon S.P., Kang S.J., Jung S.J. Rapidly growing eccrine porocarcinoma of the face in a pregnant woman. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014;25(2):715–717. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000436739.52418.97. Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SHAW M., McKee P.H., Lowe D., Black M.M. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty‐seven cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00527.x. Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tidwell W.J., Mayer J.E., Malone J., Schadt C., Brown T. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015;54(9):1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12997. Sep 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner J.J., Maxwell L., Bursle G.A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report with light microscopy and ultrastructure. Pathology (Phila.) 1982;14(4):469–475. doi: 10.3109/00313028209092129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orella J.A., Peñalba A.V., San Juan C.C., Nadal R.V., Morrondo J.C., Alvarez T.T. Eccrine porocarcinoma: report of nine cases. Dermatol. Surg. 1997;23(10):925–928. Oct 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J.B., Oh C.K., Jang H.S., Kim M.B., Jang B.S., Kwon K.S. A case of porocarcinoma from pre‐existing hidroacanthoma simplex: need of early excision for hidroacanthoma simplex? Dermatol. Surg. 2003;29(7):772–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29195.x. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshina D., Akiyama M., Hata H., Aoyagi S., Sato‐Matsumura K.C., Shimizu H. Eccrine porocarcinoma and Bowen's disease arising in a seborrhoeic keratosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007;32(1):54–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02260.x. Jan 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golemi A., Hanspeter E., Brugger E., Ruiu A., Farsad M. FDG PET/CT in malignant eccrine porocarcinoma arising in a pre-existing poroma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2014;39(5):456–458. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31828da64b. May 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason M., Siegel C.A. Do inflammatory bowel disease therapies cause cancer? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013;19(6):1306–1321. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182807618. May 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahlberg M.J., McGinnis K.S., Draft K.S., Fakharzadeh S.S. Multiple eccrine poromas in the setting of total body irradiation and immunosuppression. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006;55(2):S46–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.052. Aug 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurisu Y., Tsuji M., Yasuda E., Shibayama Y. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for s-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann. Dermatol. 2013;25(3):348–351. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348. Aug 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wildemore J.K., Lee J.B., Humphreys T.R. Mohs surgery for malignant eccrine neoplasms. Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30(12p2):1574–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30569.x. Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]