Significance

Signaling modules in living cells function and respond in a surprisingly robust way, in spite of their very noisy environment. In contrast, this is not the case for most synthetic circuits in living cells, which are usually designed and tuned in silico under specific assumptions that do not hold in the real environment of the cell. To recover the robust behavior, synthetic circuits need a means to make inference about their dynamic environment, which in turn can be used to effectively counteract it. Here we show how such inference can be implemented as biochemical modules and illustrate how this can guide the design of adaptive synthetic circuits.

Keywords: synthetic circuits, optimal filtering, noise cancellation, adaptive design

Abstract

The invention of the Kalman filter is a crowning achievement of filtering theory—one that has revolutionized technology in countless ways. By dealing effectively with noise, the Kalman filter has enabled various applications in positioning, navigation, control, and telecommunications. In the emerging field of synthetic biology, noise and context dependency are among the key challenges facing the successful implementation of reliable, complex, and scalable synthetic circuits. Although substantial further advancement in the field may very well rely on effectively addressing these issues, a principled protocol to deal with noise—as provided by the Kalman filter—remains completely missing. Here we develop an optimal filtering theory that is suitable for noisy biochemical networks. We show how the resulting filters can be implemented at the molecular level and provide various simulations related to estimation, system identification, and noise cancellation problems. We demonstrate our approach in vitro using DNA strand displacement cascades as well as in vivo using flow cytometry measurements of a light-inducible circuit in Escherichia coli.

Recent developments in synthetic biology have enabled a revolution of biomolecular engineering (1, 2), prompting numerous applications in therapeutics (3–5), biocomputing (6–8), and plant engineering (9), for instance. However, a variety of practical limitations have to be addressed before the field can achieve its full promise. Above all, engineered circuits often exhibit a substantial mismatch between in silico predictions and in vivo behavior (10). Such mismatch is largely attributed to so-called context dependencies, causing individual cells to behave differently depending on their intracellular environment (11). The latter can be understood as the congregation of environmental factors that affect the target circuit, such as the ribosomal abundance or the cell cycle stage. Variations of those factors across cells and over time—also termed “extrinsic noise” (12)—can impair a circuit’s functionality in an unpredicted way and cause total functional failure.

Because extrinsic noise arises outside a circuit, it can be handled in a more systematic fashion than intrinsic molecular noise (13), which is ultimately dictated by biophysical principles. Intuitively, if an extrinsic perturbation is present, one could in principle apply a second perturbation that steers the network into the opposite direction such that the two competing effects cancel. This idea is akin to conventional noise cancellation techniques encountered in communication systems, where a target signal (e.g., a recorded voice) is corrupted by noise (e.g., through wireless transmission) and subsequently reconstructed by reversing the effect of in a suitable way (14). Because this requires some sort of knowledge about , the most pertinent ingredient to achieve noise cancellation is a means to estimate dynamically changing noise signals [ in the example above] from available measurements. A multitude of such estimation techniques—often termed “optimal filters”—have been developed, driven by applications in control, telecommunications, and signal processing. However, the assumptions underlying existing techniques are often incompatible with the scenarios encountered in molecular biology, such as the assumptions of linearity or additive Gaussian noise associated with the well-known Kalman filter (15).

In quantitative biology, optimal filtering and related concepts have been used in the literature, either to reconstruct biochemical processes from experimental data in silico (16) or to analyze whether existing biochemical networks can act as optimal filters that process intracellular and extracellular signals (17–20). Along those lines, it has been shown theoretically that the suppression of noise is fundamentally bounded by the precision at which the noise can be estimated from the past (21). This underpins the high potential of implementing biochemical estimators that achieve such a bound. Nevertheless, the use of optimal filters for the de novo engineering of synthetic networks remains nonexistent.

Conventional statistical methods aim at inferring molecular signals or parameters based on experimental data, which have been recorded beforehand through dedicated technical devices such as flow cytometers or microscopes. In other words, the inference itself is performed in silico by the observing entity. The goal of this work is to move the observing entity inside a cell or any biochemical network of interest. To this end, we reinterpret such estimators as dynamical systems themselves and map their specification to a list of biochemical reactions.

Theoretical Results

Biochemical Signals and Sensors.

Assume a synthetic circuit requires knowledge about the abundance of a biochemical signal that it cannot access directly. For instance, could be an environmental perturbation that the circuit has to adapt to or the internal state of another dynamical system that it aims to control. In the former case, does not necessarily have a physical interpretation but rather serves as a phenomenological proxy that reflects the multitude of noise sources affecting a circuit. The synthesis rate of a protein, for instance, depends on various factors (e.g., gene dosage and ribosomal abundance) but itself may be described reasonably well by a one-dimensional quantity that fluctuates over time (22). For the sake of illustration, we assume is a one-dimensional birth–death model with parameters ρ and ϕ (Fig. 1A); we will be concerned with more general scenarios later in this manuscript.

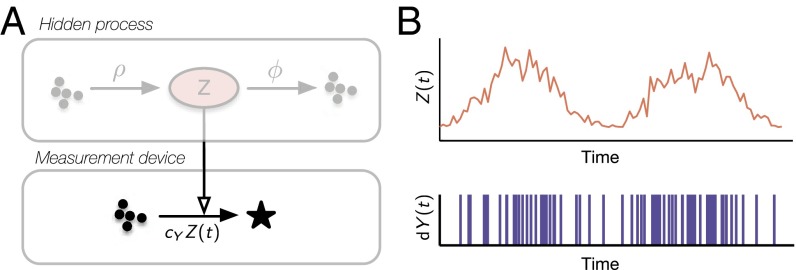

Fig. 1.

Sensing biochemical signals. (A) Schematic diagram. The noise is modeled as a birth–death process with birth rate ρ and death rate ϕ and is assumed to be observable only indirectly through a sensor reaction. The corresponding rate constant (i.e., sensor rate) determines how much information about is on average revealed per time unit. It consequently determines the precision at which can be estimated. (B) The two plots show realizations of the hidden noise and the corresponding sensor firings .

Although is assumed to be hidden to the circuit of interest, that circuit might have access to indirect readouts of . For instance, it might be able to recognize specific mRNAs which give an indication about the activity of a gene that cannot be sensed directly by the circuit. In the simplest case, this indirect readout (in the following termed “sensor”) could relate to through a single catalytic reaction, modeled by the stochastic birth process

with as a rate constant determining the speed of this reaction. Note that the symbol serves as a wildcard that will be concretized later when the sensor is interfaced with the filter circuit.

Implicitly, the sensor reaction carries information about the unknown : if one observes many firings in a short amount of time, one can conclude that was probably large, and vice versa. Mathematically, the number of reactions that fired in the time interval is a random variable that can be described as a time-varying Poisson process with rate . The differential version of this process can be viewed as a random pulse train that has value one only at the sensor firing times and zero otherwise (Fig. 1B). A complete sensor trajectory consists of the random reaction times , as opposed to most usual readouts that reveal abundances (corrupted by additive noise, for instance). Note that the informativeness of the sensor increases with , and from this perspective, large are superior to small . At the same time, however, one tries to keep the energy cost at a minimum to prevent interferences with the host cell. The resulting tradeoff highlights the need for optimal estimators that can extract as much information as possible from the sensor, especially when is small.

Optimal Signal Estimation.

The theory of optimal filtering (23) provides a mathematical framework for estimating dynamic signals from measurements . More specifically, it is centered around finding the conditional (i.e., filtering) distribution . In this context, we denote as “filter” an estimator of that is based on statistics of that distribution, such as its mean or variance. It can be shown that estimators of the form minimize the mean squared error and are therefore termed minimum mean squared error (MMSE) estimators (14). In the special case of linear dynamics and Gaussian noise, the MMSE estimator is analytically tractable through the Kalman filter. The Kushner–Stratonovich differential equation describes filters also for the more general case of nonlinear and non-Gaussian models, although their practical handling is typically challenging if not impossible. The MMSE estimator for the given birth–death process from Fig. 1A can be shown to satisfy

| [1] |

with as the estimator variance (SI Appendix, section S.1). Note that Eq. 1 can be informally rewritten as an ordinary differential equation driven by a sum of Dirac pulses , with summand k stemming from the kth reaction firing of the sensor. Between two consecutive firing times and , the estimator signal evolves deterministically. Every time a sensor reaction fires, instantaneously changes by the factor . This factor can be understood as an adaptation gain that determines how much weight is put on the correction term : if the filter is very certain [i.e., variance small], only little correction is needed, and vice versa. Unfortunately, the adaptation gain is analytically intractable because generally involves the third-order moment and so forth, leading to an infinite-dimensional system of differential equations (i.e., moment closure problem).

However, two tractable filters can be derived under the assumption of either weakly or highly informative measurements. We refer to the first one as the Poisson filter, and it is based on the assumption that is small, for instance, when available resources are scarce. Because this assumption implies that (SI Appendix, section S.1.3), the filter reduces to a single differential equation

| [2] |

The second filter, called the gamma filter, is based on the fact that for large , the filtering distribution is approximately gamma (24) (SI Appendix, section S.1.4). This filter requires a second differential equation corresponding to (SI Appendix, Eq. 20).

Taking a systems perspective, those filters are now understood as kinetic models driven by an external input . The goal is to synthesize their dynamics through simple biochemical reactions with mass-action kinetics. In the case of the Poisson filter, this is rather straightforward because the filter is already in the form of a valid rate equation. In particular, it describes the concentration of a birth–death process with parameters ρ and , respectively. Note that despite its noisy input , the estimator should be as deterministic as possible. We therefore allow it to be rescaled by a constant factor n to ensure a deterministic, high–copy-number regime (SI Appendix, section S.1.5). Overall, the Poisson filter can be implemented through only three reactions:

| [3] |

For a given n, the abundance of the species at time t is a discrete random variable which we denote by . For large n, the large copy number limit will be approached, and the filter reactions will become virtually deterministic. Note that this will not be the case for the sensor reaction, whose rate depends on the abundance of , which is not scaled by n. This gives us a way to realize the solution of Eq. 2 using chemical reactions. More precisely, for any t in the interval : . Therefore, for large values of n, the reactions in Eq. 3 give us the molecular filter realization we seek because for such values, .

In the case of the gamma filter, challenges arise because the filter equations are incompatible with biophysical rate laws. We addressed this problem by applying a suitable variable transform and implementing the transformed dynamics and and corresponding inverse transforms as standard mass-action kinetics. A detailed derivation and list of reactions can be found in SI Appendix, section S.1.5. Example trajectories of both filters for different values of are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S.1.

To quantitatively check the accuracy of the filters, we compared their empirical MSE to the MMSE obtained through numerical integration of the Kushner–Stratonovich equation. The results reflect the conditions of under which the two filters were derived. Taken together, the filters provide a reasonable approximation of the exact MMSE estimator along the entire range of (SI Appendix, Fig. S.2).

Optimal filters can typically tolerate a substantial degree of model mismatch. This has great practical relevance because the dynamic noise model is sometimes only poorly characterized. In the considered example, for instance, precise knowledge of the parameters ρ and ϕ might not be available. We performed additional simulations and found both filters to be largely robust with respect to parameter mismatch (SI Appendix, Fig. S.2). Although the Poisson filter performs generally worse than the gamma filter for little or no mismatch, it is surprisingly robust also in case of substantial parameter variations.

Ensemble Averaging.

When a filter is scaled by n, a single sensor reaction has to produce n molecules at once. Although this could be achieved, for instance, using DNA hybridization cascades, challenges arise in cellular systems where the degree to which stoichiometries can be engineered is rather limited. Ensemble averaging offers a viable and attractive alternative to filter scaling. The idea here is to achieve determinism by running n independent copies of the original (unscaled) filter and averaging these. For example, n could correspond to the number of identical plasmid replicates within a cell. Similarly, one could use a population of n isogenic cells to sense extracellular signals such as the abundance of a certain chemical in the media. Although intrinsic fluctuations will affect the individual instance , they will average out in the mixture process if n is sufficiently large. This has important practical implications. First, the resulting one-molecule sensors are much simpler to achieve using cellular mechanisms, and second, they provide a cheap way to exploit biological parallelism. This idea is related to the concept of ensemble learning (25), where a collection of noisy algorithms add up to a single accurate predictor, and we refer to these filter variants as “ensemble filters.” We show in SI Appendix, section S.2, that for large n, the ensemble Poisson filter converges to the differential equation

| [4] |

which is reminiscent of a state observer equation—a quantity frequently used in control theory. This filter variant appears particularly relevant for in vivo applications where it could be realized through multiple replicates of a single gene that has both a constitutive and an inducible promoter (see case studies below).

When comparing the ensemble Poisson filter to the Poisson filter in terms of the MSE, one finds that for any , the ensemble variant is guaranteed to achieve a lower MSE for any ρ, ϕ, and . This is due to the fact that fluctuations of the sensor are repressed in the ensemble filter, whereas this fails to be true for the Poisson filter (SI Appendix, section S.2.1). For large n, this difference can be seen by multiplying Eq. 4 with and comparing it to Eq. 2: the two equations coincide except that the term stemming from the sensor is replaced by its deterministic, noise-free counterpart .

Extensions to More General Cases.

The filter variants described above are suitable in cases where the sensor is attached directly to the unknown signal . In various practical applications, however, a circuit might require knowledge about unknown signals that are multiple steps away from the sensed species. For instance, we would like to conceive a filter circuit that only uses information of a certain gene product to make inference about the transcription factor abundance that controls it. This requires an extension of our filtering framework to general multivariate scenarios. As it turns out, the MMSE estimator of any biochemical species satisfies

| [5] |

with as the species attached to the sensor, as any other species that depends on in an arbitrary way (Fig. 2A), and as the conditional covariance of those species. The term refers to the unconditional dynamics of the mean of as dictated by the chemical master equation. Mathematically, this can be written as , with as the infinitesimal generator of the (unconditional) stochastic process . For instance, if is a birth–death process such as the one from Fig. 1A, then . Note that Eq. 5 is general, and our previously derived filters and other known estimators can be framed as special cases of it. For instance, if the components are constant parameters [i.e., ], then Eq. 5 can be understood as a continuous-time variant of the recursive least squares algorithm (26).

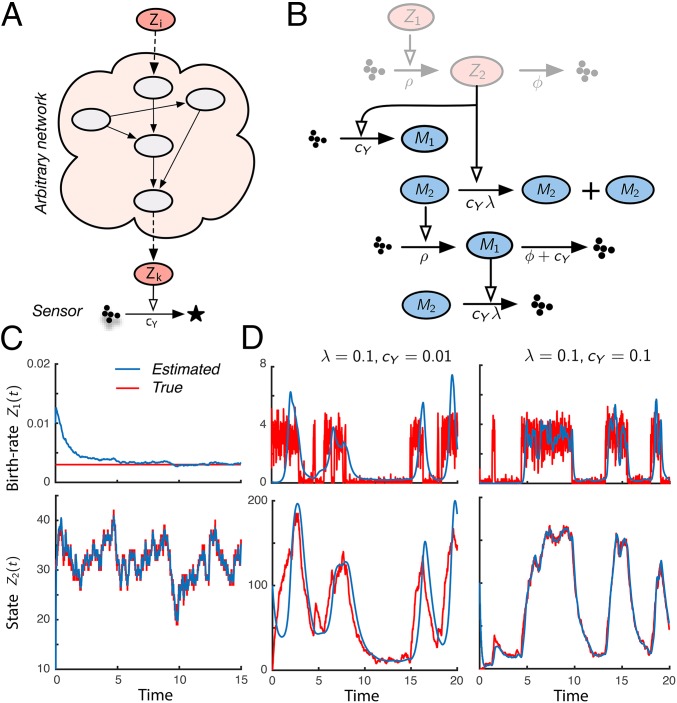

Fig. 2.

Generalized filtering circuits. (A) Schematic illustration. The signal of interest relates to a sensed signal through an arbitrary and possibly complex network. Optimal estimates of can be computed through Eq. 5. (B) The 2D system identification circuit. The red species correspond to the hidden process that consists of a birth–death process with birth and death rates and , respectively. We assume both and to be unknown (red nodes) but that can be observed indirectly through sensors. The corresponding optimal filters and are shown as green nodes. (C) Joint state and parameter inference. After a short transient, the filter is able to correctly identify the unknown birth rate (Upper). Even though the birth rate is initially far off the true value, is estimated very accurately due to the self-adjusting property of the estimator. (D) Adaptive system identification. We applied the filter from B to a system identification problem. In particular, we tried to identify a birth–death process with a complex time-varying birth rate modeled by the bistable Schloegl system (36). The results indicate that as long as the filter adapts sufficiently fast (larger λ and ), it is able to track the complex system dynamics accurately (Right). However, when the dynamics of are fast compared with the timescale of adaptation (small λ and ), the performance breaks down (Left).

Although estimator in Eq. 5 may not be directly realizable, an estimator that satisfies a close approximation of it is always achievable using molecular circuits (SI Appendix, section S.3). This will be shown in Applications and Discussion.

Applications

In the following sections, we demonstrate practical applications of our filtering circuits using two simulation studies as well as experimental data recorded in vitro and in vivo.

Adaptive System Identification.

We use a multivariate filter to solve a combined state and parameter estimation problem that is associated with a biochemical system identification task. In particular, we consider a birth–death process with unknown but static birth rate . The corresponding multivariate estimator is realizable through five elementary reactions (Fig. 2B) as shown in SI Appendix, section S.3.1. Our simulations demonstrate that the filter is able to accurately identify both and (Fig. 2C) after a short transient. Note that this filter is able to readapt to spontaneous changes in the birth rate . This suggests an application of this filter to scenarios in which the true birth rate slowly varies over time, for instance, over the duration of a cell cycle. If the filter is adjusting itself quickly enough, it should be able to track the temporal dynamics of a time-varying and possibly complex system. In the derived filter, the speed of adaptation depends on and an additional parameter λ (SI Appendix, section S.3.1). We used this filter to identify a birth–death process, whose birth rate is controlled by a stochastic bistable switch. Fig. 2D shows that if λ and are reasonably large, the filter is indeed able to closely resemble the complex switch-like dynamics.

Cancellation of Extrinsic Noise.

In the following we show how the newly developed filters could guide the design of noise-insensitive circuits. Although a more detailed view on this topic is provided in SI Appendix, section S.4, we illustrate the concept by means of an example that is representative of what is typically encountered in vivo. In particular, we consider a microRNA circuit that is deployed to mammalian cells through transient transfection. The goal of the circuit is to stably express RNA , but the rate at which it is transcribed is corrupted by contextual factors. First, we assume that each cell receives a random number of plasmid copies during deployment and that the plasmids deplete randomly as cells divide. We refer to the number of plasmid copies at time t as . Furthermore, we assume transcription to be affected by a slowly varying random process that correlates with the cell cycle (Fig. 3A). Overall, we obtain a transcription rate (Fig. 3B).

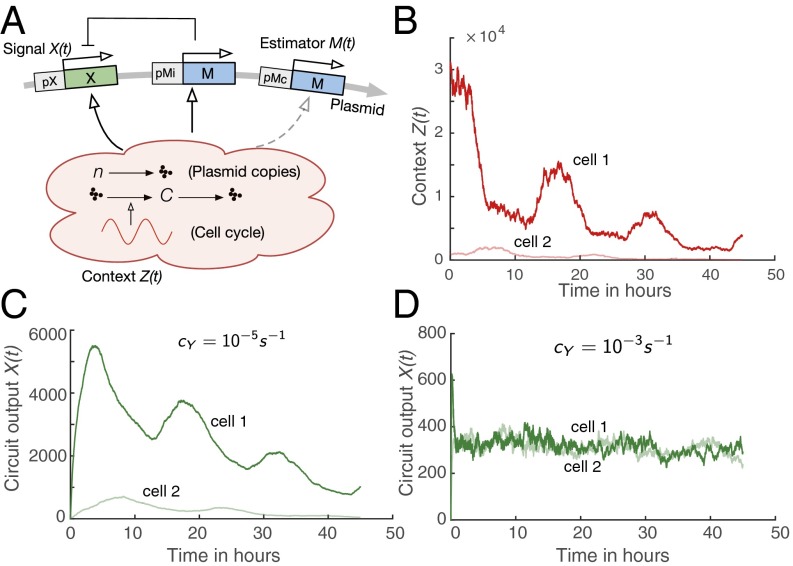

Fig. 3.

Noise cancellation using optimal filtering. (A) Schematic diagram of the microRNA circuit. The expression of the transiently transfected gene X is assumed to be context-dependent. First, it is affected by the number of plasmids present in each cell. We assume that at time , a random number of plasmids is deployed to each cell [ with and ] and that this number decreases randomly through cell division. This is modeled by a degradation reaction with rate and as the average cell cycle duration. Furthermore, we model a dependency of the transcription rate on a cell cycle-dependent factor . Overall, the transcription rate of gene X is given by . The estimator gene M is present twice on the plasmid: once attached to a Z(t)-inducible promoter pMi and once attached to a constitutive promoter pMc. Note that in practice, pMc is also likely to be affected by contextual noise. We therefore accounted for an unintended dependency of this promoter on Z(t) as well (dashed arrow). (B) Example realizations of the overall contextual noise for two different cells. Realizations of the target gene for small (C) and large (D) sensor rates . If is too small, cannot be captured sufficiently well, resulting in a poor circuit performance. In contrast, if is reasonably large, the output variability can be suppressed almost entirely such that can be expressed at a high stability across the window of transfection.

The goal is to construct an estimator of the cumulative context and to use this estimator as a repressor of through RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig. 3A). Intuitively, the two effects are expected to compensate for each other such that the overall effect of on vanishes. In fact, this idea can be framed mathematically as demonstrated in SI Appendix, section S.4.

In the considered scenario, the ensemble Poisson filter is particularly suitable to serve as an estimator because it can exploit the availability of multiple gene replicates per cell to improve its accuracy. The gene M corresponding to this filter is present twice on the plasmid, once attached to a constitutive promoter pMc and once attached to a -inducible promoter . Note that in realistic scenarios, also the constitutive version of M is likely to be affected by contextual factors. We therefore accounted for an unintended dependency of this gene on in our model. We performed stochastic simulations of the resulting circuit that accounts for both intrinsic and extrinsic (i.e., contextual) fluctuations (see SI Appendix, section S.4.4, and Fig. 3 for more details). It turns out that if the sensor rate of the ensemble Poisson filter is sufficiently large, the noise canceller performs well even though it is based on strongly simplifying assumptions [i.e., modeled as a birth–death process], and it is affected by extrinsic and intrinsic noise itself (Fig. 3 C and D). An additional case study showing noise cancellation in a bistable switch is provided in SI Appendix, section S.4.5.

In Vitro Implementation of the Poisson Filter.

As a proof of principle, we forward-engineered and tested a DNA-based filtering circuit in vitro as DNA strand displacement (DSD) cascades (6, 7, 27–29). Strand displacement is a competitive hybridization reaction where an incoming single-stranded DNA molecule binds to a complementary strand, in the process displacing an incumbent strand. This elementary mechanism allows one to directly synthesize arbitrary chemical reaction networks (30). Furthermore, because individual DSD reactions can be described by conventional bimolecular rate laws at a remarkably high precision (31), they provide a higher degree of quantitative control compared with cellular systems.

To enable a comparison of the molecular filter with its mathematical counterpart and the true value of , only the filter itself [i.e., the equation describing the dynamics of ] was implemented in vitro. The noise and respective sensor time points [i.e., the times where ] were simulated on a computer, and the latter were manually transferred to the test tube in which the filter was operated (Fig. 4A). In particular, the concentration of had to be increased by a constant value at each of those time points. Here we want to estimate the concentration of (as opposed to absolute copy numbers), and thus, with as the reaction volume associated with the virtual signal (Fig. 4A). In reference to Eq. 2 this would correspond to a scaling factor of at the level of copy numbers, with as the volume of the test tube.

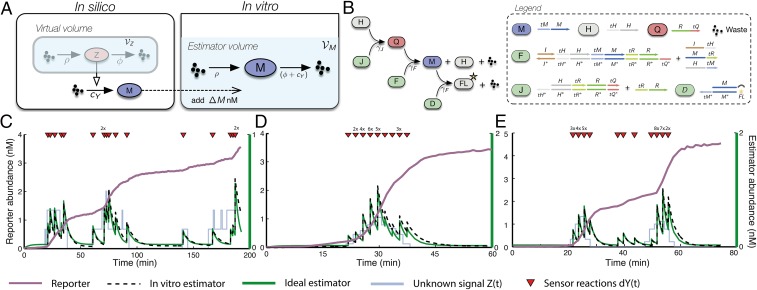

Fig. 4.

In vitro estimation of dynamic signals. (A) Experimental setup. The hidden signal and corresponding sensor reactions are simulated in silico and subsequently transferred to the reaction volume of the in vitro estimator , each time increasing its concentration by . In vitro dynamics are monitored through fluorescence experiments at acquisition intervals of 1 min. (B) Biochemical implementation of the Poisson filter as a DSD cascade. The overall circuit consists of two modules, one for production of and one for combined degradation and reporting. Strand displacement reactions are described as single events with rate parameters , , and . The desired birth and death rates ρ and are set by choosing appropriate initial concentrations of gates H and D. Every time a degradation event happens, a fluorophore is irreversibly unquenched, such that the measured fluorescence is proportional to the integral of (SI Appendix, Fig. S.10). (C–E) Experimental assessment of the estimator using three different signals. The simulated sensor time points when are indicated by the triangles (Dataset S1). If more than one of those time points fell into one acquisitions cycle, the respective multiples of were added simultaneously (indicated by the numbers above the triangles). The estimator was extracted by differentiating the measured fluorescence as described in SI Appendix, section S.6.1.6. C shows filtering results for a random realization of the birth–death process with ρ and ϕ matching the prior assumptions of the filter. In D and E, the filter was further tested using two artificially designed profiles (i.e., single- and double-pulse).

The reaction network from Eq. 2 was mapped to a DSD circuit (SI Appendix, section S.5 and Fig. S.10) under the join-fork paradigm (6, 32) and quantified experimentally using calibrated fluorescence measurements (SI Appendix, section S.6.1). An initial perturbation experiment was performed to check the circuit’s sensitivity with respect to small changes in M and to compute initial estimates of kinetic parameters (SI Appendix, section S.6.1.4). Based on those estimates, we designed three time course experiments. The corresponding fluorescence trajectories show that the in vitro filter resembles the ideal mathematical model at a remarkably high precision in all three scenarios (Fig. 4 C–E).

Ensemble Filtering in Escherichia coli.

Engineering biochemical circuits and their properties in living organisms is associated with substantial additional challenges compared with cell-free systems. It is therefore important to show that the desired circuit characteristics are attainable using cellular mechanisms. In the following, we demonstrate experimentally that a simple genetic circuit in Escherichia coli can function as an optimal filter.

To check whether our circuit is indeed able to estimate a noise signal unknown to it, we must know the noise signal being estimated. A good way to achieve this is to generate the random signal ourselves. To that end, we used an optogenetically controlled sensor to which we can apply arbitrary light sequences . This allowed us to compare the filter estimate to the true values of . In practical applications, the optogenetic sensor could be replaced by one that recognizes another signal of interest. The procedures we followed are described next.

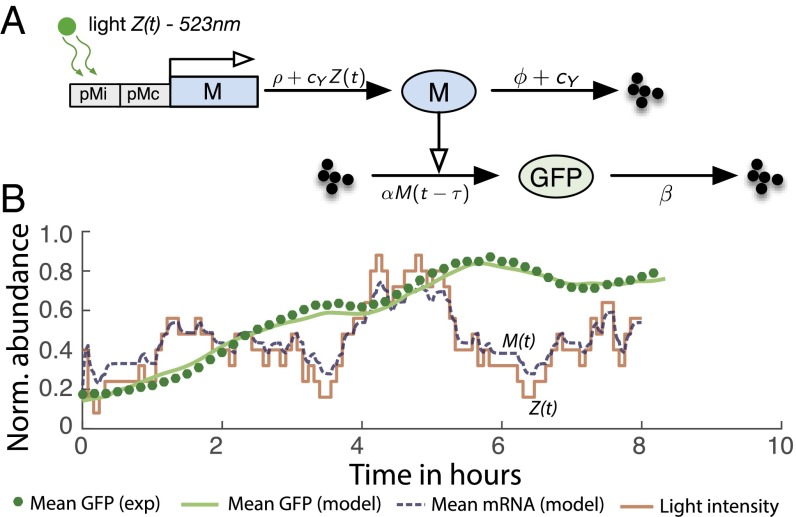

We used an optogenetic circuit encoded in plasmid pJT119b (33), which expresses a fluorescent protein (GFP) at a basal rate through a weak constitutive promoter (34). This rate can be enhanced through a second promoter that is inducible by green light (Fig. 5A). Due to this particular promoter configuration and the fact that plasmids are present in multiple copies per cell [ (35)], this circuit closely resembles an ensemble Poisson filter that optimally estimates a light signal generated according to noise dynamics with a particular set of parameters ρ, ϕ. Indeed, based on Eq. 4, there always exist a ρ and ϕ for which the optogenetic circuit functions as an optimal filter as long as the degradation rate of is larger than . To figure out these inverse optimal parameters for our specific optogenetic circuit, we performed calibration experiments using a designed light profile to infer the mRNA transcription dynamics along with the parameters α, β, and τ that account for reporter maturation and degradation. From the inferred transcription dynamics, we can get the parameters ρ, ϕ, and according to Eq. 4 (see also Fig. 5 A and SI Appendix, section S.7.5 and Fig. S.16). The inferred filter circuit parameters allow us to assess the performance that the filter would achieve in terms of its MSE (SI Appendix, Fig. S.16).

Fig. 5.

Ensemble filtering circuit in E. coli. (A) Schematic diagram. Transcription of mRNA is activated by an inducible promoter , whose activity depends on the intensity of the applied light stimulus . A basal level of transcription is present due to an additional constitutive promoter . Synthesis and degradation of protein are modeled as a delay differential equation to account for GFP maturation. To explain experimental day-to-day variability, we allowed the protein synthesis rate α to vary across experiments. (B) Filter validation. We applied a randomly generated light sequence to the circuit and compared the experimental outcome to the model predictions. The mathematical solution of GFP closely resembles the GFP abundance recorded by flow cytometry. The corresponding transcriptional response inferred from the model shows that this circuit yields accurate estimates of the light input .

Finally, we tested the function of our circuit as an estimator of . We generated a random trajectory and applied it as a light input to our optogenetic circuit (SI Appendix, section S.7.7). We found that the corresponding experimental fluorescence measurements are in very good agreement with the response predicted by the inferred filter model (Fig. 5B), indicating that the corresponding transcriptional output is indeed able to estimate with high fidelity (see SI Appendix, sections S.7.5–S.7.7, for more details).

Circuits like the one above could serve as modules for estimating dynamic transcription factor abundances from transcribed RNAs. The estimator could be optimized to specific dynamics (characterized by ρ, ϕ) by tuning the strengths of the promoters: the constitutive expression rate should be designed to be close to ρ, whereas the induced transcription rate should be close to , where k is the degradation rate constant of which should satisfy . As shown earlier in this article, the robustness of the filter with respect to mismatch in ρ and ϕ increases with the sensor rate .

Discussion

Our results illustrate that a seemingly complex filtering operation may be realizable through very simple biochemical mechanisms. This simplicity allowed us to showcase our filtering approach in vitro using DNA strand displacement cascades but also in vivo using a light-inducible gene expression circuit in E. coli.

A key strength of model-based filtering techniques is that the assumed model dynamics of are steadily corrected through a feedback control loop. This way, a filter can exploit all information about that is available a priori (e.g., its autocorrelation or mean abundance) but, at the same time, can tolerate a substantial degree of model mismatch (SI Appendix, Fig. S.2 and Figs. 2D and 3D). The latter property appears particularly relevant for synthetic biology where the true dynamics of a signal is often only poorly characterized.

We found that the proposed ensemble filter variants are favorable over normal ones when replicates of identical circuits are easy to accomplish (e.g., through multiple plasmids). By exploiting this parallelism, they lead to a damping of the sensor noise that is inversely proportional to the ensemble size n, and as a consequence, ensemble filters achieve a reduced MSE for all compared with their original counterparts.

Most importantly, however, the ensemble concept entails a general recipe for building optimal estimators of arbitrary biochemical signals, even if they are nonlinear and multiple steps away from the sensor. In particular, they can be realized from n replications of the signal of interest , extended by a sensor reaction and an additional (controlled) degradation (SI Appendix, section S.3). The individual replicates serve as stochastic simulations of to emulate its unconditional mean dynamics [i.e., ] as an n-sample Monte Carlo average. As a striking implication, the moment closure problem is bypassed, facilitating applications also to nonlinear . Another desirable side effect of replicating is that parameter and model mismatch between the assumed and true dynamics is reduced to a minimum.

Our simulation studies suggest several potential applications of optimal filters to biomolecular estimation, system identification, and the design of context-independent circuits. In contrast to trial-and-error approaches, the circuits are derived in a principled fashion under an MMSE criterion.

We believe that the ability to perform statistical computations in situ will be crucial for devising robust synthetic networks. Those will allow circuits to sense, estimate, and adapt to their environment, facilitating context-aware designs. We envision many potential applications, ranging from adaptive therapeutics to self-reporting cells that estimate and display inaccessible parameters and states.

Materials and Methods

Detailed information about mathematical derivations, simulations, and experimental procedures can be found in SI Appendix. In SI Appendix, section S.1, we provide discussions around the optimal filtering framework for biochemical networks. The ensemble and multivariate filters are described in SI Appendix, sections S.2 and S.3, respectively. SI Appendix, section S.4, introduces a mathematical framework for noise cancellation and contains details about the corresponding simulations. Rational design and experimental methods related to the DNA-based filtering circuit are provided in SI Appendix, sections S.5 and S.6. Experimental methods related to the bacterial circuit are described in SI Appendix, section S.7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Yuan Chen and Sundipta Rao for providing technical assistance to the first author while he was performing the experiments. This project was financed with a grant from the Swiss SystemsX.ch initiative, evaluated by the Swiss National Science Foundation. G.S. was supported by National Science Foundation Grant CCF-1317653.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1517109113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brophy JA, Voigt CA. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat Methods. 2014;11(5):508–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church GM, Elowitz MB, Smolke CD, Voigt CA, Weiss R. Realizing the potential of synthetic biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(4):289–294. doi: 10.1038/nrm3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lienert F, Lohmueller JJ, Garg A, Silver PA. Synthetic biology in mammalian cells: next generation research tools and therapeutics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(2):95–107. doi: 10.1038/nrm3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Z, Wroblewska L, Prochazka L, Weiss R, Benenson Y. Multi-input RNAi-based logic circuit for identification of specific cancer cells. Science. 2011;333(6047):1307–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1205527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruder WC, Lu T, Collins JJ. Synthetic biology moving into the clinic. Science. 2011;333(6047):1248–1252. doi: 10.1126/science.1206843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YJ, et al. Programmable chemical controllers made from DNA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(10):755–762. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian L, Winfree E. Scaling up digital circuit computation with DNA strand displacement cascades. Science. 2011;332(6034):1196–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1200520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon TS, Lou C, Tamsir A, Stanton BC, Voigt CA. Genetic programs constructed from layered logic gates in single cells. Nature. 2012;491(7423):249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antunes MS, et al. Programmable ligand detection system in plants through a synthetic signal transduction pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelwick R, MacDonald JT, Webb AJ, Freemont P. Developments in the tools and methodologies of synthetic biology. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2014;2:60. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardinale S, Arkin AP. Contextualizing context for synthetic biology—Identifying causes of failure of synthetic biological systems. Biotechnol J. 2012;7(7):856–866. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 2002;297(5584):1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAdams HH, Arkin A. Stochastic mechanisms in gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(3):814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay SM. Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing: Estimation Theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalman RE. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J Fluids Eng. 1960;82(1):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zechner C, Unger M, Pelet S, Peter M, Koeppl H. Scalable inference of heterogeneous reaction kinetics from pooled single-cell recordings. Nat Methods. 2014;11(2):197–202. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinczewski M, Thirumalai D. Cellular signaling networks function as generalized Wiener-Kolmogorov filters to suppress noise. Phys Rev X. 2014;4(4):041017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowsher CG, Voliotis M, Swain PS. The fidelity of dynamic signaling by noisy biomolecular networks. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):e1002965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi TJ. Implementation of dynamic Bayesian decision making by intracellular kinetics. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104(22):228104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.228104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews BW, Yi TM, Iglesias PA. Optimal noise filtering in the chemotactic response of Escherichia coli. PLOS Comput Biol. 2006;2(11):e154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lestas I, Vinnicombe G, Paulsson J. Fundamental limits on the suppression of molecular fluctuations. Nature. 2010;467(7312):174–178. doi: 10.1038/nature09333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zopf CJ, Quinn K, Zeidman J, Maheshri N. Cell-cycle dependence of transcription dominates noise in gene expression. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):e1003161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bain A, Crisan D. Fundamentals of Stochastic Filtering. Springer; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zechner C, Koeppl H. Uncoupled analysis of stochastic reaction networks in fluctuating environments. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(12):e1003942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opitz D, Maclin R. Popular ensemble methods: An empirical study. J Artif Intell Res. 1999;11:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eden UT, Frank LM, Barbieri R, Solo V, Brown EN. Dynamic analysis of neural encoding by point process adaptive filtering. Neural Comput. 2004;16(5):971–998. doi: 10.1162/089976604773135069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang DY, Seelig G. Dynamic DNA nanotechnology using strand-displacement reactions. Nat Chem. 2011;3(2):103–113. doi: 10.1038/nchem.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian L, Winfree E, Bruck J. Neural network computation with DNA strand displacement cascades. Nature. 2011;475(7356):368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips A, Cardelli L. A programming language for composable DNA circuits. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl 4):S419–S436. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0072.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soloveichik D, Seelig G, Winfree E. DNA as a universal substrate for chemical kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(12):5393–5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909380107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang DY, Winfree E. Control of DNA strand displacement kinetics using toehold exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(47):17303–17314. doi: 10.1021/ja906987s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardelli L. Two-domain DNA strand displacement. Math Structures Comput Sci. 2013;23(Special Issue 2):247–271. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson EJ, Hartsough LA, Landry BP, Shroff R, Tabor JJ. Characterizing bacterial gene circuit dynamics with optically programmed gene expression signals. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):449–455. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidl SR, Sheth RU, Wu A, Tabor JJ. Refactoring and optimization of light-switchable Escherichia coli two-component systems. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3(11):820–831. doi: 10.1021/sb500273n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stueber D, Bujard H. Transcription from efficient promoters can interfere with plasmid replication and diminish expression of plasmid specified genes. EMBO J. 1982;1(11):1399–1404. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlögl F. Chemical reaction models for non-equilibrium phase transitions. Z Phys. 1972;253(2):147–161. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.