Abstract

Previous research on the determinants of effectiveness in knowledge systems seeking to support sustainable development has highlighted the importance of “boundary work” through which research communities organize their relations with new science, other sources of knowledge, and the worlds of action and policymaking. A growing body of scholarship postulates specific attributes of boundary work that promote used and useful research. These propositions, however, are largely based on the experience of a few industrialized countries. We report here on an effort to evaluate their relevance for efforts to harness science in support of sustainability in the developing world. We carried out a multicountry comparative analysis of natural resource management programs conducted under the auspices of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. We discovered six distinctive kinds of boundary work contributing to the successes of those programs—a greater variety than has been documented in previous studies. We argue that these different kinds of boundary work can be understood as a dual response to the different uses for which the results of specific research programs are intended, and the different sources of knowledge drawn on by those programs. We show that these distinctive kinds of boundary work require distinctive strategies to organize them effectively. Especially important are arrangements regarding participation of stakeholders, accountability in governance, and the use of “boundary objects.” We conclude that improving the ability of research programs to produce useful knowledge for sustainable development will require both greater and differentiated support for multiple forms of boundary work.

Keywords: boundary organization, extension, innovation, research policy

Sustainable development is a knowledge-intensive endeavor. Efforts to improve linkages among research programs, experiential knowledge, and action on the ground have nonetheless been only partially successful. The question for scientists, program managers and donors is therefore not whether but rather how to modify program design and practice in ways that help to realize the great potential of research programs to support sustainable development (1, 2).

Boundary Work in Theory and Practice

Previous research suggests that the concept of “boundary work” provides one potentially powerful point of departure for designing research programs that better link knowledge with action (3). Originally developed to help understand efforts to demarcate “science” from “nonscience” (4), the idea of boundary work has since been applied to the interface between science and policy (5–7) and, more broadly, to the activities of those seeking to mediate between knowledge and action (8, 9).* The central idea of boundary work is that tensions arise at the interface between communities with different views of what constitutes reliable or useful knowledge. If an impermeable boundary emerges at the interface, no meaningful communication takes place across it. However, if the boundary is too porous, personal opinions mix with validated facts, science gets mixed with politics, and the special value of research-based knowledge fails to materialize. Active boundary work is therefore required to construct and manage effectively the interfaces among various stakeholders engaged in harnessing knowledge to promote action (10).

Scholarship on boundary work is rapidly expanding (6, 7, 11, 12). In general, it hypothesizes that boundary work is more likely to be effective in promoting used and useful research to the extent that it exhibits at least three key attributes: (i) meaningful participation in agenda setting and knowledge production by stakeholders from all sides of the boundary; (ii) governance arrangements that assure accountability of the resulting boundary work to relevant stakeholders; and (iii) the production of “boundary objects,” defined as collaborative products such as reports, models, maps, or standards that “are both adaptable to different viewpoints and robust enough to maintain identity across them” (13).

There remain, however, two concerns regarding these widely shared hypotheses about successful boundary work. First, with a few notable exceptions (14), most of the relevant evidence derives from case studies of single efforts in a few countries of North America and Europe. The hypotheses are nonetheless increasingly being used to guide reform in potentially different contexts of the developing world (15, 16). Second, even where there is some agreement on the attributes that characterize effective boundary work, there is little on which strategies for organizing boundary work are most likely to yield such attributes in particular circumstances (17, 18).

The research reported here sought to address these concerns through the comparative analysis of boundary work in the family of programs on integrated natural resource management carried out under the auspices of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), one of the world’s largest and most experienced global research organizations seeking to foster sustainability in the developing world. We focused on boundary work conducted within the CGIAR’s Alternatives to Slash and Burn (ASB) program, “a global partnership of research institutes, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), universities, community organizations, farmers’ groups, and other local, national, and international organizations… [seeking] to raise productivity and income of rural households in the humid tropics without increasing deforestation or undermining essential environmental services” (19). ASB has been operating since 1994 and now has 12 “benchmark sites” around the world. Lessons drawn from its experience with boundary work should thus be of significant broader interest. (SI Text includes more information on the CGIAR and ASB). Several of the present authors have been involved in ASB’s work in multiple ways (SI Text). We have published elsewhere detailed accounts of how ASB has functioned and of its impacts on knowledge and action relevant to sustainable development (20, 21). Here we extend that work to explore two more specific questions. First, to what extent does ASB’s history of efforts to link knowledge with action confirm, reject, or call for extension of existing hypotheses about the attributes of successful boundary work? And second, what does the ASB experience have to say about how local context shapes the challenges facing boundary work, and thus the strategies for carrying it out effectively?

Reconceptualizing Boundary Work: A Framework

We discovered two big things from our exploration of boundary work in ASB. First, we encountered a far greater variety of boundary work than the literature had led us to expect. Second, we determined that much of that variety—and the success of strategies that produce it—can be understood in terms of the sources and uses of the knowledge that boundary work engages.

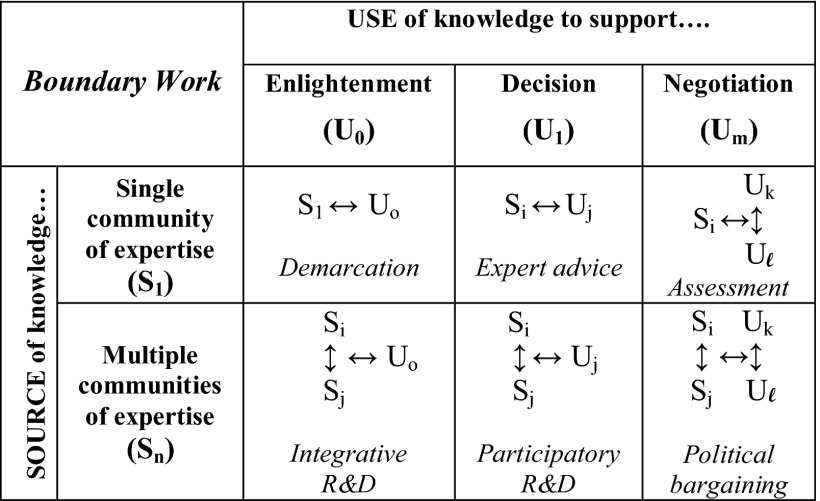

We developed the conceptual framework set forth in Fig. 1 as a means to better understand the variety of boundary work at ASB. The columns of the framework address the uses of knowledge, i.e., the purpose for which knowledge consumers deploy it. We distinguish use for (i) enlightenment, or the advancement of general understanding that is not targeted at specific users but may influence decisions through a diffuse process of percolation (22) (Uo); (ii) “decision support” of choices made by a single relatively autonomous user such as a farmer or minister (U1); and (iii) “negotiation support” of bargaining or other political interactions among multiple users (Um). The rows of the framework address the sources of new knowledge. We distinguish knowledge that is seen by users as originating within (i) a single, relatively homogeneous community of knowledge producers sharing similar norms of evidence and argument (e.g., the discipline of soil science) (S1); or (ii) multiple heterogeneous communities of knowledge producers with potentially conflicting norms (e.g., social vs. natural sciences, or laboratory vs. traditional knowledge; Sn). The individual cells of the framework reflect how the particular combinations of knowledge sources and uses determine the challenges facing boundary work in particular contexts. The arrows in Fig. 1 represent the potential for two-way interactions among the relevant sources and users of knowledge. Reality almost certainly offers up more of a continuum of sources and uses than our framework of discrete classes suggests. We have nonetheless found the discrete framework to be a helpful way to organize our thinking and exposition. (The conceptual framework of Fig. 1 is a simple version, adequate for this study, of the more general use/source framework that is presented in Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Context of boundary work as defined by sources and uses of knowledge.

How can the “effectiveness” of boundary work be evaluated? This question is illuminated by a growing body of research showing that technical information in policy contexts is more likely to be influential to the extent that it is perceived by stakeholders as satisfying the criteria of saliency, credibility, and legitimacy (SCL; Table 1). Producing knowledge in ways that meet any one of these criteria for any one user is relatively simple. Producing it in ways that meet all three criteria in ways that are simultaneously satisfactory to multiple stakeholders is necessary for science to have much chance of advancing collaborative action, but can be very hard indeed to achieve (3, 23, 24). In this article, we build on recent work applying the SCL criteria to evaluate the effectiveness of boundary work (17, 25, 26).

Table 1.

SCL criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of boundary work

| Criterion | Concerns addressed |

| Saliency | Relevant to the decision or policy? |

| Credibility | Technically adequate in handling of evidence? |

| Legitimacy | Fair, unbiased, respectful of all stakeholders? |

The following sections present our findings regarding how such effectiveness is influenced by the way that the boundary work attributes of participation, accountability, and boundary objects are handled in each of the six use/source contexts defined in Fig. 1.

Use of Knowledge for Enlightenment

The simplest boundary work we found in ASB occurred where the relevant user was the scientific research community itself together with the diffuse debate on agricultural alternatives that scientists sought to inform. ASB often looked on new information primarily as a source of enlightenment, that is, to advance basic understanding with no concerns for immediate application (Fig. 1, Uo). The central challenge for the program’s boundary work in this context was to meet the SCL credibility criterion (Table 1): sorting new knowledge claims to establish which would be accepted into the body of accepted fact that ASB, as a research program, was prepared to stand behind. If the boundary regulating such acceptance were too permeable, solid facts, idiosyncratic experience, and mere conjecture would become so mixed as to undermine the knowledge foundations on which further research sought to build deeper understanding of the world. If the boundary were too impermeable, new findings and ideas could gain no traction with the research community. Understanding would stagnate.

Boundaries Between New Discoveries and Established Knowledge.

ASB addressed the same challenge facing all research communities: deciding whether to accept a particular new claim into its body of accepted, reliable knowledge (Fig. 1, S1Uo). ASB usually confronted this conventional challenge of boundary work with conventional scientific processes for quality control such as significance tests and standards for experimental replicability. Not surprisingly, ASB research programs dealt quite well with these tasks through normal peer-review activities (20).

Boundaries Between Research Disciplines.

More challenging were the circumstances in which ASB sought to stimulate the integration of expertise from multiple sources of knowledge, often involving multiple methods or rules of evidence (Fig. 1, SnUo). ASB work in this context confronted two distinct challenges of boundary work and developed distinctive strategies for dealing with them.

ASB leadership recognized early on that understanding the sustainability of alternative human land uses at the tropic forest margins would require the integration of research across the natural and social sciences (21). Such integration, however, posed significant challenges for ASB, embedded as it was in the natural science culture of the CGIAR. The initial temptation of the natural scientists who dominated the early ASB was simply to “do their best” at addressing the complex social issues they encountered at their field sites. This approach, however, produced mediocre research that threatened the credibility of the entire program. Differences among disciplines in jargon and rules of evidence, plus an initial lack of mutual respect, made the creation of knowledge judged to be credible by all seem almost beyond reach. As the program matured, however, successful strategies for boundary work did emerge and exhibited most of the attributes, noted earlier, that the literature has hypothesized.

Participation.

The joint participation of natural and social scientists was initially achieved by issuing contracts for them to participate in problem-focused “thematic working groups” that encouraged two-way communication across disciplines. Especially effective was the program’s use of joint field trips to the ASB benchmark research sites. The “retreat-like” character of these field visits created “safe spaces” that were widely cited by participants as powerful mechanisms for fostering more meaningful exchanges across the gulf normally separating natural and social science researchers (21).

Accountability.

The central governance challenge in the SnUo context was to assure that the ASB agenda was not captured by either natural or social scientists (or their respective norms of “good research”). Such mechanisms were neither formal nor strong at ASB, especially during the early stages of the program. However, the presence on the ASB’s original Global Steering Group of international partner institutions with a relatively strong commitment to social science perspectives provided an important counterbalance to CGIAR’s natural science biases in the early stages of the program.

Boundary objects.

ASB created a variety of boundary objects that were jointly “owned” by natural and social scientists. One of the first of these was the development of shared protocols for data collection developed to guide and coordinate work across the ASB benchmark sites (27, 28). There was little truly interdisciplinary scholarship involved in this work. However, the commitment of natural and social scientists to contribute their respective parts to a common whole clearly advanced mutual understanding and respect. Real interdisciplinary integration eventually followed, perhaps most clearly illustrated by the bioeconomic models developed by ASB and its partners from Brazil’s Embrapa (29). These models came to serve ASB researchers as a widely cited and emulated illustration of the potential benefits of true interdisciplinary integration, creating products judged to be credible by natural and social scientists.

Boundaries Between Context-Specific and Generalizable Research.

A second challenge confronted by ASB was the integration of research conducted by scientists from its “national” and “international” networks. ASB leaders were well aware that “global” research programs often end up with agendas set by “cosmopolitan” researchers drawing from their international networks. “Local” scholars—largely based in national institutions in the developing world—are then relegated to tasks of running the experiments and collecting the data. Moreover, ASB faced the broader but related challenge of integrating research focused on generalizable results with research emphasizing context-specific understanding and solutions. The key to effective boundary work for addressing these tensions in the ASB turned out to be primarily the program’s commitment to do so: its “Core Values and Operating Principles” made full partnerships between local and international researchers the touchstone of all ASB activities.

Participation.

The Principles highlighted the commitment of the program to full participation of all researchers in agenda setting, resource allocation, and credit for findings and publications. Full transparency of decisions and decision making was also emphasized. These commitments were observed in practice and credited by participants with playing an important role in program success.

Accountability.

Governance provisions to assure that these goals were in fact achieved came through representation of local and international researchers on ASB’s Steering Group, with a preference for national partners.

Boundary objects.

The most important boundary objects created in the work of mediating between norms of context-specific and generalizable research were the program’s benchmark sites for studying human use of forest margins throughout the humid tropics. Each site developed a research program tuned to local needs and capacities, but also committed to exploring certain common questions and to using some common methods, metrics, and protocols. Research papers produced at the sites reflected shared credit across cosmopolitan and local researchers (28).

Use of Knowledge for Decision Support

ASB’s goals assured that much of its activity would take place at the interface between research and application. We found, however, that the challenges addressed by such boundary work were radically different depending on whether the “user” or consumer of information was a single, relatively autonomous decision maker (Fig. 1, U1) or participants in a more complex negotiation among multiple political interests (Fig. 1, Um). We address the latter case in the next section. Here we focus on the use of knowledge for decision support (Fig. 1, U1).

The challenge for ASB’s boundary work carried out to mediate the use of knowledge for decision support (i.e., U1) was more complex than its boundary work to foster enlightenment alone (i.e., Uo). In particular, for knowledge to be used in support of decision making, it needed to be perceived by decision makers as not only scientifically credible but also as salient to their needs (Table 1). An insufficiently permeable boundary between research and decision making risked that scientists would set their research priorities by imagining what decision makers wanted to know rather than by learning from them what they actually needed. Decision makers would remain ignorant of what good research and development might realistically have to offer. However, an overly permeable boundary risked the politicization of science, with decision makers using—and even directing—research primarily to support decisions they had already made. The same permeability, however, also risked the “scientization” of politics: decision-makers avoiding responsibility for grappling publicly with fundamental questions of “who gets what” by repackaging them as “merely” technical issues to be resolved by experts they controlled (30).

In our investigations of ASB, we found two distinctive types boundary work being carried out to address these challenges of harnessing science for decision support: one between scientists and farmers, the other between scientists and policy-makers.

Boundaries Between Scientists and Farmers.

Early work by the CGIAR had used a largely one-directional “extension” model of technology transfer. By the time ASB was organized in the 1990s, the shortcomings of this approach were widely recognized. These included its failure to integrate farmers’ with researchers’ knowledge and its tendency to define agendas in terms of researchers’ solutions rather than farmers’ problems (31). Much progress had been made toward adopting a bidirectional, collaborative model of “farming systems research” and development. ASB enthusiastically adopted this model, but nonetheless struggled to shape the boundary work needed to implement it successfully. The following sections detail what we found regarding the determinants of successful boundary work.

Participation.

Scientists and farmers did participate in joint priority setting, research, and evaluation activities at most ASB sites. Partnerships were formalized at a few sites but elsewhere were largely informal and opportunistic, often triggered by outsiders’ visits associated with project funding cycles or evaluations. Nonetheless, ASB’s boundary work generally succeeded in developing trust and rapport, resulting in changes to both research agendas and the uptake of new findings. Scientists participated in these partnerships partly from their perception of the value of local knowledge to their own research, partly in response to the formal commitment by ASB that its work would be “grounded in local reality through long-term engagement with farmers and community groups.” Farmers participated for a variety of reasons, ranging from interest in scientific findings to the expectation that participation in the research activities would lead to major development projects.

Accountability.

Formal mechanisms to hold ASB’s farming systems research accountable to both farmers and scientists were rare, generally occurring only when required by a particular funding arrangement. Much more common were informal consultations conducted in the context of field trips and site visits. ASB’s commitment to the use of participatory research methods was the prime mechanism to guarantee farmers an opportunity for voicing dissatisfaction with the direction of ASB activities.

Boundary objects.

The joint creation of tangible products by scientists and farmers played a significant role in linking research with action at the ASB sites. Drawings, maps, and physical models of relevant landscapes were the most valued knowledge products (Fig. S2 illustrates an example). Also important were collaborative field trials, on-farm nurseries, and the production of training materials on effective land use practices.

Boundaries Between Scientists and National Policy Makers.

Governments in the regions addressed by ASB looked to the program for scientific information that would help them to choose among alternative land uses. ASB encountered two big challenges. First, the initial impetus for the program had come in large part from international environmental advocates who framed the problem as deforestation, the cause as slash-and-burn land use by smallholder farmers, and the solution as the development of alternatives to such practices (28). ASB’s early work showed that this initial top-down framing was at odds with scientific findings and realities on the ground. It sought to move beyond the initial framing imposed on it toward a more contextualized, bottom-up effort empowering local decision-makers to help set locally salient research priorities. Second, many of the scientists working with ASB at the local level were employed by national ministries or international NGOs that had strong political agendas of their own. This relationship called into question local scientists’ ability to conduct truly independent research. ASB’s principal challenge was then to strengthen boundaries separating these scientists’ research from their employers’ politics. ASB experimented with a variety of boundary work strategies for creating research that would support better decisions by policy-makers.

Participation.

Participation of scientists and policy makers in formal joint discussions about decision-support priorities for ASB was never regularized. Rather, it occurred intermittently and informally at meetings driven by specific policy or research needs. Significantly, however, the capacity to recognize and take advantage of such opportunities depended crucially on the development of sustained collegial relationships between senior program scientists and policy makers. These were fostered formally in Indonesia, where ASB maintained a small office within the Ministry of Forestry. Informal engagement was also effective, notably in Brazil and Thailand, where the resident ASB scientists devoted substantial time to the development and maintenance of informal connections with relevant officials.

Accountability.

Accountability for the collaborative development of research agendas that reflected needs of decision support was provided through a number of channels. Many of these were embedded in the informal collegiality noted above. A key role was played by “national champions”: individuals, usually scientists, who had the respect of both the research and policy communities. ASB sought to cultivate champions and bring them onto its official steering group, thus helping to assure that regional decision-support needs would find a voice in the setting of research priorities. Formal planning workshops were also convened at the national and regional levels. At these workshops, ASB scientists collaborated with staff advising relevant policy makers in the development of work plans. The tone of these workshops was generally of an advisory rather than governing nature. They were backed, however, by potential hard sanctions: ASB (like all CGIAR programs) needed official government permission to operate in host countries. However, ASB could also exit (along with its funding) from countries unwilling to work closely enough with it to achieve desired impacts on practice.

Boundary objects.

Boundary objects played important roles in assuring that ASB research provided useful support to national level decision makers. These included synoptic country reports, specially prepared “policy briefs” on key issues, and models focused at regional scales. A common feature of the most influential boundary objects was their tailoring to local decision-makers’ needs and language. An especially noteworthy innovation was the “ASB Matrix,” a succinct (one page) table summarizing what ASB research had discovered about the tradeoffs among alternative land uses, denominated in economic, social, and environmental indicators, reflecting the concerns of policy-makers in a specific country (an example is provided as Table S1).

Use of Knowledge for Negotiation Support

The most complex forms of boundary work we found in ASB emerged in the context of multiple knowledge users with potentially conflicting objectives (Fig. 1, Um). The challenge of creating useful information in such politicized situations included the previously discussed need to assure users of the salience and credibility of knowledge. However, in this context, there was an additional need to assure users of the legitimacy of processes for mobilizing knowledge (Table 1). Successful boundary work needed to convince all users that the process of linking knowledge with action had not been biased in support of another’s agenda. Failed boundary work could result in one or more parties rejecting knowledge that might have been useful for negotiations, not because of doubts regarding the credibility or saliency of that knowledge but because of perceptions that the questions asked or evidence considered may have been stacked unfairly in another’s favor (32).

Boundaries Between ASB and Multinational Negotiations.

ASB’s boundary work in the S1Um context is illustrated through its role in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), in which it led the component addressing the tropical forest margins: the ASB-MA (SI Text) (33). The ultimate challenge for ASB was to introduce usable scientific information into the often-intense conflicts between advocates of biological conservation and of economic development at national and global scales. Its contribution was credited by major stakeholders from all sides of the political debate with creating a salient, credible, and legitimate knowledge base on which to build subsequent negotiations (20). We summarize in the subsequent sections what we found to be the most significant elements of ASB’s relatively successful strategy for boundary work in the S1Um context.

Participation.

The special challenge of participation in the ASB-MA was to find ways of effectively engaging the enormous range of interested parties. These included individual farmers in the ASB benchmark sites, ministerial users from multiple nations, representatives of diverse global organizations, and scientists working at all scales. In the face of a potentially crippling supply of interested stakeholders, ASB-MA adopted a strategic approach to participation. For scientists, it drew on the 250 researchers from 50 institutions around the world then involved in ASB research, and complemented those with an open call to qualified outside experts for expressions of interest in participating in the assessment. From this pool, the ASB-MA selected scientists from a strategic mix of countries, disciplines, and institutions. Needs of local users were systematically identified through community level assessments regularly conducted at each of the ASB benchmark sites, supplemented by surveys conducted especially for the assessment. Finally, ASB-MA conducted consultations on user needs with policy shapers at the subnational and national level throughout ASB’s domain (21).

Accountability.

The ASB-MA faced two challenges of accountability. First, the participants in the ASB research program needed assurances that their findings reached the MA without distortion. Second, global users from the conservation and development communities needed assurances that the assessment was not biased toward the action agenda of one or the other. ASB-MA provided such assurances by subjecting itself to the parallel but separate governance structures of the ASB and the MA (SI Text). No formal linkage between the ASB and MA governance mechanisms was sought or achieved, although one of the conditions for authorization of the ASB-MA by the MA Board was the existence of a broadly representative governing body for ASB, a role convincingly played by the ASB Global Steering Group.

Boundary objects.

The principal boundary object created by the ASB-MA was its assessment report (34). This document—and the process that commissioned, produced, and reviewed it—effectively spanned the worlds of policy-driven concerns and science-based findings. Many subsidiary products of the assessment also served as boundary objects on narrower topics—for example, the policy briefs prepared on particular topics such as restoration of degraded landscapes and the forces driving tropical deforestation (35). The ASB Matrix that played such a prominent role as a boundary object in the S1U1 context noted earlier was also effectively used in the ASB-MA.

Boundaries Between Multiple Knowledge Sources and Multiple Users.

The most novel, challenging, and complex instances of boundary work we found in ASB are those taking place in the context characterized by the lower right corner of Fig. 1: multiple sources of knowledge (i.e., Sn) entrained in negotiations among multiple stakeholders (i.e., Um). For ASB, such contexts were ubiquitous. Specific instances ranged from integration of conflicting expert views on how different regimes of land access would affect conservation and economic interests to construction of shared understanding for use in pricing payments for ecosystem services (32, 36).

To illustrate how ASB structured its boundary work in this context, we summarize here our findings on the program’s boundary work to facilitate sustainable development in the forests of Indonesia’s Sumberjaya region, where upland coffee production was said to be endangering downstream environmental services. Conflict between the government and smallholders had resulted in promulgation of a new community forest management plan with new rules of forest tenure [Hutan Kemasyarakatan (HKm)], but implementation was contentious and slow (SI Text). ASB [and later its spinoff program, Rewarding the Upland Poor for Environmental Services (RUPES), also operating under the CGIAR) persuaded the local government to allow it to help experiment with different HKm requirements to achieve better results (37, 38). ASB-RUPES rapidly discovered, however, that merely conducting research in decision-support mode was inadequate. As two of the present authors wrote at the time, “The real-world human impact on natural resources derives from a large number of individual decisions, made with different access to sources of knowledge and information, with different technical means to organize exploitation, and with different objectives, constraints, priorities, and strategies. The best we can hope for is a process of negotiations among stakeholders that leads to modification of the individual decisions to produce superior outcomes from the broader social perspective” (32). ASB-RUPES therefore began to develop a new mode of engagement, which it eventually called negotiation support. The approach did involve a significant amount of classic agroforestry research and development, but also included unconventional elements of capacity building and mediation. Four years into this engagement, an independent analysis documented that the HKm program facilitated by ASB-RUPES had made a significant contribution to sustainable development in Sumberjaya (37, 39). Several novel features of ASB-RUPES’ boundary work contributed to this success.

Participation.

There was deep distrust among the stakeholders in the management of Sumberjaya forests: smallholders, regional officials, NGOs, and national forestry experts. ASB-RUPES diagnosed that, were it to provide support to only one of these stakeholders, the program would be dismissed by the others as just another advocate picking sides in the conflict. It therefore devoted substantial effort to cultivating relationships with all the major stakeholders, listening to their questions, treating their knowledge and beliefs respectfully but critically, and eventually bringing them together in carefully “neutral” meetings that produced shared knowledge.

Accountability.

The deficit of trust noted earlier meant that no domestic institution existed that parties would accept as guarantor of ASB-RUPES’ efforts. The program therefore invested in a variety of bilateral confidence building measures, meant to assure each stakeholder individually of the salience, credibility, and, above all, of the legitimacy of ASB-RUPES’ efforts. By all accounts, this worked remarkably well, drawing in no small part on the reputation in the region of the program’s “parent”: CGIAR’s World Agroforestry Centre [also known as the International Center for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF)]. However, its success was even more dependent on the commitment and reputation of a few key individuals than on any formal institutional mechanism.

Boundary objects.

Multiple boundary objects were created to stabilize parts of ASB-RUPES’ engagement in the Sumberjaya community forestry effort. Most significant and unusual, however, was the revised HKm agreement itself, and the community forestry permits that flowed from it. These created a legally binding framework accepted by all stakeholders. The crucial contribution from ASB-RUPES was its scientific finding that coffee agroforestry could meet the income goals of farmers and the conservation goals of government. All parties were initially skeptical, but the participatory and transparent research of ASB-RUPES changed minds, and created the key “win/win” option that underpinned the HKm system.

Discussion

The present study has evaluated the role of boundary work for understanding efforts to harness research for natural resource management in the developing world. Others have also begun to explore related questions, with most focusing on boundary work in natural resource management in developed world contexts (9, 40–42) and a few examining the special challenges of carrying out such work in the developing world (14, 15, 43). Nonetheless, a recent comprehensive survey conducted for the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) concluded that, despite consensus on the need for boundary work in strengthening science-policy dialogue in developing countries, there is no consensus on how boundary work is actually carried out there, or on how its effectiveness can be improved (17). Our research findings provide a partial remedy to this situation.

Context Matters: Differentiating Challenges of Boundary Work.

We conclude that much of the lack of consensus noted by ODI is almost certainly caused by an insufficiently differentiated view of the kinds of boundary work being performed. Our study of ASB shows that there is, in fact, a rich variety of boundary work being carried out even within a single research program. Much of the observed variety can be understood in terms of context within which the boundary work is performed—in particular, the sources and uses of knowledge that it engages (Fig. 1). We propose that our contextual framework for boundary work captures not only the ASB experience, but also much of the boundary work described in the literature. [Complementary frameworks proposed by Andrews (44) and Michaels (18) are discussed in SI Text].

The “source” dimension of our framework is important because it differentiates situations in which who counts as an expert or what counts as knowledge are potentially at issue. A great deal of research by scholars of science, technology, and society has focused on the implications of such distinctions (45). Our studies suggest, however, that—at least for the understanding and design of boundary work—the intended use of knowledge (i.e., the columns of Fig. 1) is even more significant, primarily because it determines the criteria by which the authoritativeness or influence of knowledge is assessed by those who might act on it. We therefore organize the discussion of our results in terms of the use dimension of Fig. 1.

Enlightenment.

Where the intended use of knowledge is simply enlightenment (i.e., Uo), the principal challenge for boundary work is to construct a perception on all sides of the boundary regarding the credibility of the knowledge produced. This covers the classic “demarcation” of science from nonscience (i.e., S1Uo) as originally described by Gieryn (4) and as generally pursued through strategies of peer review. It also turns out to be the principle challenge faced by efforts seeking to advance understanding by bringing together multiple kinds of knowledge (i.e., SnUo), whether through interdisciplinary scientific research (25) or through the integration of indigenous and scientific knowledge (43).

Decision.

Where the intended use of knowledge is the support of decision making by a single, relatively autonomous agent (i.e., U1), the challenge of boundary work expands to include the saliency of knowledge. This is the context addressed in the work of Jasanoff (5) and Guston (46) applying boundary work concepts to the problem of science advice to governments. In the context of a single community of relevant expertise serving as the source of knowledge (i.e., S1U1), this covers what has been called “client-oriented advising” (44) as well as the long tradition of scientific advice to leaders in government (47). The challenge remains essentially the same, although the solutions are more complicated, when multiple communities of expertise are called on by single decision makers (i.e., SnU1), as in so-called farming systems research and other participatory forms of analysis in which decision-makers take an active role (41, 48).

Negotiation.

Finally, when the intended use of knowledge is to inform negotiation among participants in seriously politicized contexts (i.e., Um), the challenge of boundary work widens once again to include its legitimacy. Relatively well understood is the case in which potentially conflicted parties may seek out a single authoritative source of knowledge (i.e., S1Um) in the form of scientific assessments such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or MA (23, 49). More complex are the cases in which multiple parties are likely to mobilize the knowledge sources that support their particular interests (i.e., SnUm), and the role of boundary work is to move beyond the resulting politicization of science to shape a broadly accepted common knowledge base to support negotiations (32, 50).

This last case—SnUm in our framework, or what others have called “participatory joint fact-finding” (44)—can be seen as not only the most difficult but also the most general context for boundary work.† All the other contexts described here and captured in Fig. 1 can be thought of as limiting cases of SnUm in which the number of competing sources of knowledge or the number of competing political interests in the use of knowledge have been reduced to one. This suggests that a general theory of boundary work might begin here, rather than with the especially simple case of “demarcation” (i.e., S1Uo) that was the focus of the seminal work on the subject. In particular, a perspective that places the SnUm context as the most general boundary work challenge would need to place questions relating to the politics of expertise much more centrally in discussions of the design and evaluation of boundary work and organizations than has heretofore been the case. Such a perspective would emphasize that context matters, but also that context is to some extent chosen by relevant actors. It would stress that both the producers and users of knowledge therefore have a responsibility to reflect on the political implications of the contexts in which they choose to interact with one another (8, 17, 51).

Strategies Follow Context.

The different contexts of boundary work captured in the framework of Fig. 1 help to make sense of what has correctly been characterized as the lack of consensus regarding appropriate strategies for making such work successful (17). We discuss our findings under headings reflecting what the literature about boundary work in the developed world has hypothesized to be the determinants of success.

Participation.

Our ASB study strongly supports the hypothesis that effective boundary work requires meaningful participation of key actors from each of the communities (potentially) divided by the boundary. However, our results suggest that who constitutes “key actors” differs with context in ways determined by the use and source of knowledge, i.e., by the position of the boundary work in the framework of Fig. 1. Moreover, successful strategies for engaging meaningful participation varied along the same dimensions. Thus, in the SnUo context, all the key participants were research scientists, albeit from different and sometimes apparently incompatible disciplinary traditions. Initial tensions growing from different research styles and questions of interest were bridged through formal commitments by scientists to work together on common problems. In contrast, in the highly politicized context of SnUm, ASB found that its boundary work needed to bring together not only scientists from multiple disciplines, but also farmers, regional politicians, and national experts. The bridges forged among these groups were less formal than in the SnU1 case. They were also highly pragmatic, with the potential chaos of multiple-stakeholder debates circumvented through a process built around a series of bilateral engagements between ASB and each of the other actors.

We conclude that participation of key actors is indeed necessary for effective boundary work, as has been proposed in the literature. However, the most useful guidelines for selecting which participants are “key” seem more likely to come from a negotiator or mediator’s perspective rather than a scientist’s. Important screening questions should address who would need to change their beliefs or behaviors based on the knowledge in question, who could block action based on the knowledge, and who needs to certify the knowledge as credible to those actors. Moreover, whatever the resulting list of key actors whose participation needs to be secured, it is clear that effective boundary workers will find ways to avoid engaging them all at once. Instead, they will often serve as “shuttle diplomats,” engaging key actors sequentially and iteratively rather than simultaneously.

Accountability and governance.

The existing literature on boundary work in the developed world emphasizes the importance of formal governance arrangements to make boundary work accountable to the different communities involved. In contrast, ODI’s survey of developing countries found relatively little concern over governance of science–policy interactions (17). In our studies of ASB, we observed very different approaches to accountability depending on the context of the boundary work. For expert advice to government (i.e., S1U1), ASB’s most important contribution was to help create and strengthen a boundary separating the expert and political roles of local civil servants. These individuals, although often excellent scientists, had few safe means of separating what they knew as scholars from what regulations required of them as civil servants. By providing an independent group of scientific peers for these civil servants, ASB provided a safe space within which they could differentiate their roles. In other cases, particularly in dealing with external donors to ASB research (i.e., Uo), accountability arrangements were formal, but tended to secure donors’ interests rather than interests of local users. In highly politicized contexts (i.e., Um), there were virtually no formal accountability arrangements, reflecting the lack of institutions to enforce them.

We conclude that the formal requirement for “dual accountability” postulated in the literature does not hold as a general matter in contexts such as those engaged in by ASB in the developing world. Instead, a much more fluid and informal set of governance arrangements—more often mediated by individuals than by organizations—seemed to be the norm for ASB’s boundary work. Its informal modes of governance may not have served as effectively as the more formal governance arrangements for advisory committees and such that are common in North America and Europe. However, they often worked in the ASB regions. They did so not by imposing unrealistic demands on the thin organizations available there, but rather through the intermediary of trusted individuals who could vouch for the fairness and thus legitimacy of ASB’s boundary work efforts. Advocates of boundary work should not uncritically impose the legalistic accountability structures with which they may be most familiar onto efforts to link knowledge with action in the developing world.

Boundary objects.

Our findings support the hypothesis that successful boundary work focuses on the production of boundary objects. We documented a great variety of ways in which agreements among different communities on questions, data and conclusions were embodied in shared boundary objects. Indeed, in a number of our cases, actors’ perceptions were significantly reshaped by their shared creations—an example of the higher-order function of boundary objects that has been discussed under the heading of “standardized packages” in the literature (6, 52). Several of the boundary objects we observed appeared in multiple contexts, such as maps, models, and the ASB matrix of tradeoffs among alternative land uses. The most important finding of our work, however, is that successful boundary objects are tailored to specific contexts. Thus, the most complex boundary object we found—the HKm community forestry agreement in Indonesia (i.e., SnUm)—is unique to its circumstances. In addition, the models that show up almost everywhere are also differentiated: computable models in the context of boundary work across disciplines (i.e., SnUo), physical models at the boundary of researchers and farmers (i.e., SnU1), and scale-appropriate conceptual models when used in science advice to policy makers (i.e., S1U1). A similar pattern holds for the maps that show up as important boundary objects, but in quite different forms, across the contexts we observed.

We conclude that effective boundary work will almost always produce tangible boundary objects. However, arguments about whether maps or models or contracts constitute the most significant boundary objects may be less informative than efforts to improve the “fit” of boundary objects to the context in which they are deployed.

Generalized Findings.

Beyond the context dependent findings discussed earlier, we found that an essential contribution of boundary work in rural development is building capacity to articulate users’ demand for technical information and to convey technical information into the “field.” Both of these functions are taken for granted in most of the literature on boundary work. Our research suggests they should not be.

Beyond this general need to build capacity for boundary work, our research suggested two specific challenges facing boundary workers in rural development. First is the need for boundary work to integrate multiple forms of knowledge, in particular the contextualized knowledge of practice with the generalized knowledge emerging from research. Much of the knowledge needed to inform effective action in our cases was of the former sort. Formal, generalized knowledge from international research programs clearly had a contribution to make, but only if it could be integrated with—rather than displace—the rich contextual knowledge of local farmers and researchers. This integration posed significant problems not only of communication and translation, but also of epistemology (e.g., how to combine “uncertainty” estimates of farmers with those of scientists). Successful boundary work in ASB’s rural development contexts needed to make such problems much more central to its activities than seems to be the case for most western models.

A second challenge facing boundary work in rural development is the extreme politicization of formal knowledge. The relationship between knowledge and power is not, of course, unremarked in the existing literature on boundary work in the developed world. Nonetheless, a central feature of the reality we encountered in the field was both the fact and the presumption that scientific knowledge was being used by state and business interests to control development activities of rural land users. The demands on boundary work and workers to construct the legitimacy of formal knowledge in the eyes of various stakeholders were thus much greater than those we had encountered in existing western case studies.

We conclude that boundary work may be most generally conceived of as a negotiation support process engaged in creating usable knowledge and the social order that creates and uses that knowledge. The design of boundary organizations in decision support mode that is stressed in much of the literature can be seen as a recognizable and important subset of such a general negotiation support formulation. However, for the extremely asymmetric cases of power distribution that characterized our (and others’) rural development cases, the explicit attention to managing power contained in the negotiation support formulation appears to be essential to good boundary work. Implementing this realization would constitute a major departure from the apolitical, one-directional “transfer” models that still inform much of the dialogue and practice of science for development. The principal policy implication of our work is that improving the ability of global research programs to produce useful knowledge for sustainable development will require greater and more differentiated support for multiple forms of boundary work.

Methods

Findings reported here are derived from three principal sources of data. The first is an independent assessment of the first decade of ASB experience, carried out by a team led by one of the authors (W.C.C.) at the request of the Science Council of the CGIAR. The full method and data are published elsewhere (20). The second is a systematic self-assessment of ASB run by one of the authors (T.P.T.) involving 42 ASB researchers in an online consultation. This was structured following an analytical framework on “harnessing science and technology for sustainability” derived from studies of other comparable cases (21). The third is our recently completed field project examining the practices and evaluating the outcomes of the CGIAR’s RUPES program, a spinoff of the ASB (53). Further details are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Climate Program Office, National Science Foundation Award SES-0621004; the Italian Ministry for Environment, Land, and Sea through its support of the Harvard University Sustainability Science Program; and the CGIAR’s support of the Alternative to Slash and Burn Programme and the Rewarding Upland Poor for Environmental Services Program of the World Agroforestry Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: W.C.C. reviewed the programs that are the focus of this research for the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). T.P.T. did, and M.v.N. does, direct one of those CGIAR programs. D.C. works for one of those programs.

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “Linking Knowledge with Action for Sustainable Development” held April 3–4, 2008, at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC. The complete program and audio files of most presentations are available on the NAS Web site at www.nasonline.org/SACKLER_sustainable_development.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*The term “boundary organizations” is sometimes used interchangeably with “boundary work” in the literature. We find it more illuminating to focus on the “work” and to treat as an empirical question whether that work is performed by formal organizations or by informal networks or by individuals.

†We prefer the term “negotiation support” because is better reflects the intensely political character of the boundary work we observe in such contexts for natural resource management in the developing world.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0900231108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.ICSU–ISTS–TWAS . Science and Technology for Sustainable Development. Series on Science for Sustainable Development No. 9. International Council for Science; Paris: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Bank . World Development Report 1998-1999: Knowledge for Development. World Bank; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash DW, et al. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8086–8091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231332100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gieryn T. Boundary work in professional ideology of scientists. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48:781–795. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jasanoff S. The Fifth Branch: Science Advisors as Policymakers. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guston DH. Boundary organizations in environmental policy and science: An introduction. Sci Technol Human Values. 2001;26:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellström T, Jacob M. Boundary organisations in science: From discourse to construction. Sci Public Policy. 2003;30:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Kerkhoff L, Lebel L. Linking knowledge and action for sustainable development. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2006;31:445–477. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mollinga PP. Boundary work and the complexity of natural resources management. Crop Sci. 2010;50:S-1–S-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jasanoff S. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. Routledge; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans R. Demarcation socialized: Constructing boundaries and recognizing difference. Sci Technol Human Values. 2005;30:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raman S. Introduction: Institutional perspectives on science-policy boundaries. Sci Public Policy. 2005;32:418–422. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Star SL, Griesemer JR. Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc Stud Sci. 1989;19:387–420. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohl C, et al. Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Sci Public Policy. 2010;37:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristjanson P, et al. Linking international agricultural research knowledge with action for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5047–5052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807414106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingiri AN. Experts to the rescue? An analysis of the role of experts in biotechnology regulation in Kenya. J Int Dev. 2010;22:325–340. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones N, Jones H, Walsh C. Political Science? Strengthening Science-Policy Dialogue in Developing Countries. Overseas Development Institute Working Paper No. 294. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaels S. Matching knowledge brokering strategies to environmental policy problems and settings. Environ Sci Policy. 2009;12:994–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alternatives to Slash and Burn . ASB Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins: About ASB. Alternatives to Slash and Burn Programme/International Center for Research in Agroforestry; Nairobi: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark WC, Contreras A, Harmsen K. Report of the External Review of the Systemwide Programme on Alternatives to Slash-and-Burn (ASB): Evaluation and Impact Assessment of the ASB Programme. Report No. TC/D/A0770E/10.06/500. Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research Science Council Secretariat, Food and Agriculture Organization; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomich TP, et al. Integrative science in practice: Process perspectives from ASB, the Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2007;121:269–286. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss CH. Policy research in the context of difuse decision making. Policy Studies Rev A. 1982;6:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell RB, Clark WC, Cash DW, Dickson NM, editors. Global Environmental Assessments: Information and Influence. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Research Council . Analysis of Global Change Assessments. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollinga PP. Boundary Work: Challenges for Interdisciplinary Research on Natural Resource Management. Bonn University; Bonn, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.White DD, et al. Credibility, salience, and legitimacy of boundary objects: Water managers’ assessment of a simulation model in an immersive decision theater. Sci Public Policy. 2010;37:219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez PA, Palm CA, Vosti SA, Tomich TP, Kasyoki J. Alternatives to slash and burn: challenge and approaches of an international consortium. In: Palm CA, Vosti SA, Sanchez PA, Ericksen PJ, editors. Slash-and-Burn Agriculture: The Search for Alternatives. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2005. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palm CA, Vosti SA, Sanchez PA, Ericksen PJ. Slash-and-Burn Agriculture: The Search for Alternatives. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson EA, et al. An integrated greenhouse gas assessment of an alternative to slash-and-burn agriculture in eastern Amazonia. Glob Change Biol. 2008;14:998–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weingart P. Scientization of society - politicization of science. Zeitschrift Fur Soz. 1983;12:225–241. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byerlee D, Harring L, Winkelmann DL. Farming systems research: Issues in research strategy and technology design. Am J Agric Econ. 1982;64:897–904. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Noordwijk M, Tomich TP, Verbist B. Negotiation support models for integrated natural resource management in tropical forest margins. Conserv Ecol. 2001;5:21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millennium Ecosystem Assessment . Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. World Resources Institute; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomich TP, et al. Forest and Agroecosystem Tradeoffs in the Humid Tropics. A Crosscutting Assessment by the Alternatives to Slash-and-Burn Consortium Conducted as a Sub-Global Component of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Alternatives to Slash-and-Burn Programme; Nairobi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alternatives to Slash and Burn . Forces Driving Deforestation. ASB Policy Brief No. 6. Alternatives to Slash and Burn Programme; Nairobi: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomich TP, Verlarde SJ. Negotiation Support in Indonesia. ASB Impact Case No. 2. Alternatives to Slash and Burn Programme/International Center for Research in Agroforestry; Nairobi: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colchester M, et al. Facilitating Agroforestry Development through Land and Tree Tenure Reforms in Indonesia: Impact Study and Assessment of the Role of ICRAF. ICRAF Southeast Asia Working Paper No. 2. International Center for Research in Agroforestry; Bogor, Indonesia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusters K, de Foresta H, Ekadinata A, van Noordwijk M. Towards Solutions for State vs. Local Community Conflicts Over Forestland: The Impact of Formal Recognition of User Rights in Krui, Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum Ecol. 2007;35:427–438. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pender J, Suyanto S, Kerr J, Kato E. Impacts of the Hutan Kamasyarakatan Social Forestry Program in the Sumberjaya Watershed, West Lampung District of Sumatra, Indonesia. International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cash DW. “In order to aid in diffusing useful and practical information”: Agricultural extension and boundary organizations. Sci Technol Human Values. 2001;26:431–453. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr A, Wilkinson R. Beyond participation: Boundary organizations as a new space for farmers and scientists to interact. Soc Nat Resour. 2005;18:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klerkx L, Leeuwis C. Establishment and embedding of innovation brokers at different innovation system levels: Insights from the Dutch agricultural sector. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2009;76:849–860. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid RS, et al. Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;113:4579–4584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900313106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrews CJ. Humble Analysis: The Practice of Joint Fact-Finding. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hackett EJ. The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guston DH. Stabilizing the boundary between US politics and science: The role of the Office of Technology Transfer as a boundary organization. Soc Stud Sci. 1999;29:87–111. doi: 10.1177/030631299029001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Golden W. Worldwide Science and Technology Advice to the Highest Levels of Governments. Pergamon; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buizer J, Jacobs K, Cash D. Making short-term climate forecasts useful: Linking science and action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;113:4597–4602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900518107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zehr S. Comparative boundary work: US acid rain and global climate change policy deliberations. Sci Public Policy. 2005;32:445–456. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuinstra W. European air pollution assessments: Co-production of science and policy. Int Environ Agreements. 2008;8:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lebel L, Garden P, Luers A, Manuel-Navarrete D, Giap DH. Knowledge and innovation relationships in the shrimp industry in Thailand and Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;113:4585–4590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900555106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujimura J. Crafting science: Standardized packages, boundary objects and ‘translation’. In: Pickering A, editor. Science as Culture and Practice. Univ Chicago Press; Chicago: 1992. pp. 168–211. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McNie EC, et al. Boundary Organizations, Objects and Agents: Linking Knowledge with Action in Agroforestry Watersheds. Report of a Workshop Held in Batu, Malang, East Java, Indonesia, 26–29 July 2007. Report No. 80. International Center for Research in Agroforestry; Nairobi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.