Abstract

Objective:

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder associated with obesity. Human and animal studies showed a direct relationship between leptin level and obesity, however, results from different studies were mixed. This study investigated the status of leptin level in PCOS and its relationship with body mass index (BMI) in a group of Iranian women with PCOS.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 40 women with PCOS and 36 healthy women were assigned to experimental and control groups, respectively. Those in the PCOS group were not prescribed any medications for 3 months prior to the study. Fasting blood samples were then collected during the 2nd or 3rd day of menstruation for laboratory measurement of serum total leptin, blood glucose (fasting blood sugar), serum insulin, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone (LH).

Results:

Mean BMI of the PCOS and control groups were 26.62 ± 4.03 kg/m2 and 23.52 ± 2.52 kg/m2, respectively (P = 0.006). The mean total leptin in the PCO group was also 10.69 ± 5.37 ng/mL and 5.73 ± 2.36 ng/mL in the control group (P = 0.0001). A significant relationship was found between leptin level and BMI as well as LH level among women with PCOS (P < 0.05). However, there was no significant correlation between leptin and insulin (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

The results of this study indicated an increased leptin level among women with PCOS that positively associated with BMI and LH.

Keywords: Body mass index, insulin, leptin, polycystic ovary syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine system disorder among women of reproductive age with a prevalence of 6–25%.[1] The diagnosis of PCO is usually based on the presence of at least two of the three following criteria: (1) Ovulatory dysfunction, (2) biochemical or clinical signs of hyperandrogenism, and (3) polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography (USG).[2]

This syndrome has adverse effects on the quality of life and associated with several medical complications including cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity.[3,4,5]

Obesity is common in more than the half of women with PCO. The central fat distribution (android obesity) exacerbates the risks of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.[1]

In addition to this fact that obesity involved the peripheral tissue, the intra-abdominal fat increased in women with PCOS, which is independent of obesity.[6]

Fat tissue secretes bioactive cytokines and adipokines, including adiponectin, leptin, and resistin.[7] Some evidence suggested an association between dysregulated expression of leptin and the onset of obesity-related pathologies including PCOS.[8,9]

Leptin is an anorexigenic peptide hormone which secreted by adipocytes and circulates in the plasma as a free or protein-bound adipokine.[10] Leptin decreases appetite, increases energy expenditure, and reduces the production of neuropeptide Y from the hypothalamus. Neuropeptide Y increases food intake and after a long-term administration leads to obesity.[11] Leptin may also have a role in reproductive function, acting at many levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.[12] Circulating leptin levels have been positively correlated with body fat independent of PCOS according to some studies.[13,14] However, some studies have not shown significant differences in serum leptin levels in women with PCOS when compared with age- and body mass index (BMI)-matched controls.[15,16] In this study, we attempted to investigate both the leptin level among PCOS as well as its relationship with BMI among a group of PCOS women referred to reproductive clinics.

METHODS

The ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants. During 6 months study period (December 2014 to May 2015), we evaluated 84 women with a complaint of primary or secondary infertility lasting for 2–12 years who referred to our IVF clinic. All subjects underwent a complete screening session included laboratory, imaging, and physical examination. Patients with adrenal or hypothalamic disorders, Cushing's syndrome, hypothyroidism, and hyperprolactinemia were excluded from the study. Moreover, none of patients had received any medications that affected hormonal concentrations, for at least 3 months before the study. Eight women excluded from the study and total 76 remained patients were divided into following groups.

Control

Infertile patients due to tubal block with no other pelvic abnormality and male factor infertility (healthy women with the normal-sized ovary, regular menstrual cycles, and no sign of hyperandrogenism).

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Infertile patients who were diagnosis as PCOS based on Rotterdam consensus criteria. the presence of at least two of the following features: (1) Oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea; (2) biochemical and/or clinical evidence of hyperandrogenemia; and (3) polycystic ovaries in USG. Oligomenorrhoea was defined as menstrual periods that occur at intervals of >35 days, with only four to nine periods in a year, and amenorrhoea as the complete absence of menstruation. Clinical hyperandrogenemia was defined as the presence of hirsutism or acne. Biochemical hyperandrogenemia was defined as serum testosterone levels >0.9 ng/mL, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate levels >2000–4100 ng/mL depending on age, or free androgen index >5. Ovaries in USG were defined as polycystic when they included either ten or more follicles measuring 2–9 mm in diameter or their volume was >10 cm3.

Blood samples were obtained after an overnight fasting and sera were centrifuged and stored at − 40°C for the laboratory assessment. All were reviewed for their fasting blood glucose, insulin, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), prolactin, and serum leptin level.

All serum samples were assayed for leptin with immunoradiometric assay (IRMA; REF-DSL-23100; Diagnostic Systems Laboratories INC. 445 Medical Center Blvd; Webster, TX, 77598, USA) with assay sensitivity of 0.10 ng/ml. Samples were also evaluated for TSH (assay sensitivity 0.011 μIU/ml), LH (assay sensitivity 0.07 μIU/ml), FSH (assay sensitivity 0.3 μIU/ml), prolactin (assay sensitivity: 0.3 ng/ml) by a two-site chemiluminescence sandwich immunoassay system (Bayer Diagnostics Corporation, Tarrytown, NY, USA). Apart from this, radioimmunoassay was used to assay serum insulin (using commercial Kit from Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA with an assay sensitivity of 1.3 μIU/ml) level. Estimation of blood glucose was done by the glucose oxidase method.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software, version 20. The independent t-test was used for comparison of means of quantitative variables. If needed, based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the Mann–Whitney U-test was also used. The Pearson correlation coefficient test was used to assess relationships of quantitative variables. The Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to assess relationships of qualitative variables.

RESULTS

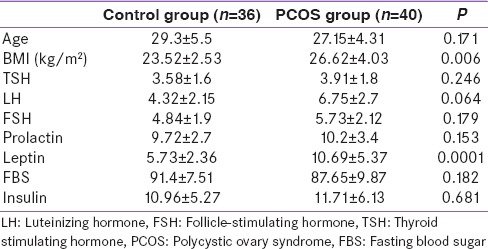

From the 76 study participants, 40 patients in PCOS group and 36 patients in control group were studied. Both groups were comparable regarding to age, TSH, and prolactin [Table 1]. As shown in Table 1, the mean fasting blood sugar (FBS), LH, FSH, and fasting insulin levels were not significantly differ between study groups. Mean BMI of the PCOS and control groups were 26.62 ± 4.03 kg/m2 and 23.52 ± 2.52 kg/m2, respectively (P = 0.006). The mean leptin levels were 10.69 ± 5.37 and 5.73 ± 2.36 ng/mL in patients with PCOS and controls, respectively. This means considerable elevation in leptin levels in the PCOS women as compared to controls (P = 0.0001).

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics and laboratory assessments

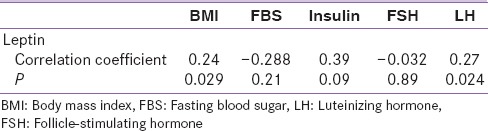

When the correlation between serum leptin and other variable study among PCOS patients were analyzed, the Pearson correlation analysis revealed only a positive correlation between leptin and BMI and also LH level. However, there was no significant correlation between leptin and insulin, FBS and FSH [Table 2].

Table 2.

Correlations of leptin and other variables in polycystic ovary syndrome group

DISCUSSION

PCOS, the common dysovulatory infertility, is characterized by chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenemia.[17] These features manifest with advancement of age and gradual increase of adipose tissue,[18] which are often linked to leptin and its receptor.[19] Leptin seems to be directly associated with obesity by preserving homeostasis of energy with reduced food intake and increased energy spending.[20] In the present study, the possibility of a relationship between leptin and BMI in women with PCOS was investigated. Our results indicate that serum leptin is significantly higher in PCOS women compared with controls. This finding is comparable with the study of Mohiti-Ardekani and Taarof, which showed elevated level of serum leptin in 27 Iranian women with PCOS.[21] This result also supports the findings of other studies which showed elevation of serum leptin in women with PCOS.[22,23,24,25] Olszanecka-Glinianowicz et al. recognized considerably higher serum leptin level in PCOS subjects compared to age- and BMI-matched NC group. Furthermore, they observed that the serum leptin level was significantly higher in obese PCOS patients compared to lean PCOS and obese non-PCOS patients.[26] However, some studies have reported no significant difference in serum leptin levels of PCOS women with age- and BMI-matched controls.[27,28] Baig et al. in their study revealed that, compared to controls, PCOS women had higher serum leptin levels but it was not significantly different.[29] Telli et al.,[30] in the study of fifty PCOS women, also reported nonsignificant higher leptin levels in PCOS patients compared to controls.

In our study, serum leptin level is significantly correlated with BMI in PCOS women and this result is corroborated with other studies.[1,19,31] This finding is clearly expected because leptin is predominantly synthesized by adipocytes, and higher BMI results in higher fatty tissue and increase synthesize of leptin.

Moreover, in our study, no association found between leptin level and insulin level. Previously, Chakrabarti suggested that hyperleptinemia in PCOS may be have a masking effect on hyperinsulinemia.[19] Insulin could increase leptin mRNA in adipocytes and has a possible role in stimulating leptin secretion.[32] Therefore, the elevated leptin in PCOS women may be a secondary consequence of insulin-stimulated synthesis of leptin. On the other hand, leptin reduces glucose-mediated insulin secretion through its receptors in the hypothalamus and also reduces its action at the cellular level.[33]

In our study, there is a significant positive relationship between leptin and LH which confirms the findings of Mohiti-Ardekani and Taarof.[21] Sir-Petermann et al. found no correlation between leptin secretion pulses and LH and leptin level does not increase during night time.[34] This may be due to the fact that during amenorrhea, leptin plays a possible role as a primary signal in receiving LH secretion pulses. A relationship between LH pulses and leptin in mid-luteal and early follicular phases has led to speculation that leptin fluctuations regulate LH plasma intensity every minute.[34] On the other hand, it has been reported that leptin has a direct regulatory action in ovarian folliculogenesis.[35] Furthermore, leptin has been shown to modulate LH-stimulated estradiol production in the ovary.[36] Although, leptin is extensively present in reproductive tissues, its correlation with reproductive hormones is still obscure.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicated an increased leptin level among women with PCOS that positively associated with BMI and LH. However, there was no significant correlation between leptin and insulin. The interactions of gonadotropins, insulin, and leptin are very complex, and correlation of leptin with reproductive hormones is still poorly understood.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broekmans FJ, Fauser BC. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrine. 2006;30:3–11. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gateva A, Kamenov Z, Mondeshki TS, Bilyukov R, Georgiev O. Polycystic ovarian syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia) 2013;52:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tock L, Carneiro G, Togeiro SM, Hachul H, Pereira AZ, Tufik S, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea predisposes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:244–51. doi: 10.4158/EP12366.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajuk Studen K, Jensterle Sever M, Pfeifer M. Cardiovascular risk and subclinical cardiovascular disease in polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Horm Res. 2013;40:64–82. doi: 10.1159/000341838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmina E, Bucchieri S, Esposito A, Del Puente A, Mansueto P, Orio F, et al. Abdominal fat quantity and distribution in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and extent of its relation to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2500–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannerås-Holm L, Leonhardt H, Kullberg J, Jennische E, Odén A, Holm G, et al. Adipose tissue has aberrant morphology and function in PCOS: Enlarged adipocytes and low serum adiponectin, but not circulating sex steroids, are strongly associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E304–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecke SB, Morsch DM, Spritzer PM. Association between adipose tissue expression and serum levels of leptin and adiponectin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:4292–6. doi: 10.4238/2013.February.28.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecke SB, Mattei F, Morsch DM, Spritzer PM. Abdominal subcutaneous fat gene expression and circulating levels of leptin and adiponectin in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2044–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yannakoulia M, Yiannakouris N, Blüher S, Matalas AL, Klimis-Zacas D, Mantzoros CS. Body fat mass and macronutrient intake in relation to circulating soluble leptin receptor, free leptin index, adiponectin, and resistin concentrations in healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1730–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messinis IE, Milingos SD. Leptin in human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:52–63. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Messinis IE, Messini CI, Anifandis G, Dafopoulos K. Polycystic ovaries and obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:479–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plati E, Kouskouni E, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Boutsikou M, Kaparos G, Baka S. Visfatin and leptin levels in women with polycystic ovaries undergoing ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan BK, Chen J, Hu J, Amar O, Mattu HS, Adya R, et al. Metformin increases the novel adipokine cartonectin/CTRP3 in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1891–900. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber TM, Franks S. Adipocyte biology in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;373:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svendsen PF, Christiansen M, Hedley PL, Nilas L, Pedersen SB, Madsbad S. Adipose expression of adipocytokines in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: The complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arikan S, Bahceci M, Tuzcu A, Kale E, Gökalp D. Serum resistin and adiponectin levels in young non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:161–6. doi: 10.3109/09513590903247816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakrabarti J. Serum leptin level in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Correlation with adiposity, insulin, and circulating testosterone. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:191–6. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.113660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crujeiras AB, Carreira MC, Cabia B, Andrade S, Amil M, Casanueva FF. Leptin resistance in obesity: An epigenetic landscape. Life Sci. 2015;140:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohiti-Ardekani J, Taarof N. Comparison of leptin blood levels and correlation of leptin with LH and FSH in PCOS patients and normal individuals. JSSU. 2010;17:353–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atamer A, Demir B, Bayhan G, Atamer Y, Ilhan N, Akkus Z. Serum levels of leptin and homocysteine in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and its relationship to endocrine, clinical and metabolic parameters. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:96–105. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorry A, White DM, Franks S. Infertility in polycystic ovary syndrome: Focus on low-dose gonadotropin treatment. Endocrine. 2006;30:27–33. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:1:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantzoros CS, Cramer DW, Liberman RF, Barbieri RL. Predictive value of serum and follicular fluid leptin concentrations during assisted reproductive cycles in normal women and in women with the polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:539–44. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pehlivanov B, Mitkov M. Serum leptin levels correlate with clinical and biochemical indices of insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14:153–9. doi: 10.1080/13625180802549962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Madej P, Nylec M, Owczarek A, Szanecki W, Skalba P, et al. Circulating apelin level in relation to nutritional status in polycystic ovary syndrome and its association with metabolic and hormonal disturbances. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:238–42. doi: 10.1111/cen.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramanand SJ, Ramanand JB, Jain SS, Raparti GT, Ghanghas RR, Halasawadekar NR, et al. Leptin in non PCOS and PCOS women: A comparative study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2014;3:186–93. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bideci A, Camurdan MO, Yesilkaya E, Demirel F, Cinaz P. Serum ghrelin, leptin and resistin levels in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:578–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baig M, Rehman R, Tariq S, Fatima SS. Serum leptin levels in polycystic ovary syndrome and its relationship with metabolic and hormonal profile in Pakistani females. Int J Endocrinol 2014. 2014:132908. doi: 10.1155/2014/132908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Telli MH, Yildirim M, Noyan V. Serum leptin levels in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:932–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Gharib MN, Badawy TE. Correlation between insulin, leptin and polycystic ovary syndrome. J Basi Clin Reprod Sci. 2014;3:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vidal H, Auboeuf D, De Vos P, Staels B, Riou JP, Auwerx J, et al. The expression of ob gene is not acutely regulated by insulin and fasting in human abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:251–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI118786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dagogo-Jack S, Fanelli C, Paramore D, Brothers J, Landt M. Plasma leptin and insulin relationships in obese and nonobese humans. Diabetes. 1996;45:695–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sir-Petermann T, Recabarren SE, Lobos A, Maliqueo M, Wildt L. Secretory pattern of leptin and LH during lactational amenorrhoea in breastfeeding normal and polycystic ovarian syndrome women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:244–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sir-Petermann T, Maliqueo M, Palomino A, Vantman D, Recabarren SE, Wildt L. Episodic leptin release is independent of luteinizing hormone secretion. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2695–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.11.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson C, Lindell K, Svensson E, Bergh C, Lind P, Billig H, et al. Expression of functional leptin receptors in the human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4144–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]